Incorporating Small Data into Your Business and Life

What polarized the Internet beyond anyone’s imagination was a simple—or maybe not so simple—striped dress.

The dress, worn by a guest at a wedding ceremony held on the remote Hebridian island of Colonsay, was posted on Tumblr by a member of the wedding band, who asked her followers for their opinion: was the dress blue with black lace fringe, or white with gold lace fringe? “I was just looking for an answer because it was messing with my head,” said Caitlin McNeill, a 21-year-old singer and guitarist.1 Unfortunately, the answer led to even more disagreement. To one set of eyes, the dress appeared to be blue-black, and to a second it appeared to be white-gold. The dress photo soon migrated to Facebook, Twitter and Buzzfeed, which published a poll, “What Color Is This Dress?” that at one point attracted more than 670,000 people simultaneously, breaking all previous Buzzfeed records for traffic.2

Never mind that the original dress, in fact, was blue and black, and retailed for £50 at Roman Originals, a UK fashion chain.3 The robust debate revealed that the differences in how we see color are based entirely on how our brains process visual information. Individual differences in color vision are fairly common, it turns out, and can be attributed to the 6 million or so tiny cones in the back of the human eyeball, known as photoreceptors, that process color in different ways, depending on our genes. Quoted in CNN.com, Dr. Julia Haller, the chief ophthalmologist at WillsEye Hospital in Philadelphia, said, “Ninety-nine percent of the time, we’ll see the same colors . . . But the picture of this dress seems to have tints that hit the sweet spot that’s confusing to a lot of people.”4 Another expert concluded, “This clearly has to do with individual differences in how we perceive the world.”5

That humans are prone to seeing the world in different ways—while still being more similar than we ever imagine—is what this book is about.

By now you know I’m Danish by birth—that is to say I’m not American, French, Spanish, English, Scottish, Irish, Brazilian, Australian, Swiss, Kenyan, South African, German, Italian, Russian, Chinese, Japanese, Vietnamese, Filipino, Austrian, Greek, Guatemalan, Chilean, Argentinian, Colombian, Mexican or a native of any other of the world’s 196 countries. More importantly, as a forensic investigator of emotional DNA, I’ve somehow managed to come up with brands or innovations not despite of my outsider’s status, but because of it. Familiarity, in fact, is at best counterproductive, and at worst, paralyzing.

A few years ago, when Pepsi asked if I would help them improve the public perception of their soft drink, of course I said yes. But only a few days into the job, I had to acknowledge that my perspective, my senses and my instincts were all compromised. Pepsi—its taste, its bubbles, its cans, its bottles, its advertising—was just too familiar. I had no distance from the brand, no frame of reference about desire, or craving, my own or other people’s. I couldn’t think straight. I couldn’t get inspired. I couldn’t do my job.

My solution was to get rid of all the Pepsi cans from my refrigerator and kitchen cabinets, so I could better observe and analyze my own responses to craving. I asked friends who were liable to offer me a Pepsi when I visited if they wouldn’t mind doing the same. Physically and psychologically, the next six weeks were an ordeal. I got headaches, found it hard to function normally and, at night, dreamed about Pepsi. The good news is that when the six weeks was up, I had managed to stimulate a response in myself and the other Pepsi drinkers I knew. I had become, again, a stranger to the everyday, an alien to the commonplace.

Working with Pepsi wasn’t the first time I’ve carried out Subtext Research on myself. The best insights always begin with ourselves. Having interviewed 2,000 or so consumers across the world, it seems only fitting to turn my methodology inward. As self-confident as I may come across sometimes onstage, when I go home to my hotel room at night, I still have a stubborn need for confirmation and validation. It all goes back to my own childhood insecurities. I can suppress them, or pretend they don’t exist, but they’re always there. Over the years I’ve looked on with interest, and sometimes dismay, at how the brands I surround myself with reflect my own confidence (and occasional lack of it).

The first, of course, is LEGO. (Growing up, I didn’t just build my own LEGOLAND, I also slept in a LEGO bed.) The second brand is Aeronautica Militare, a fashion line I wrote about earlier in this book.

Growing up, I wasn’t entirely sure what Aeronautica symbolized. I knew only that I liked its patches and wanted to buy one of its shirts. At the time I didn’t know that Aeronautica had any military significance, which, consciously or unconsciously, can be irresistible to a child anxious to find a sense of belonging and identity. Aeronautica and its logos are visually arresting, and it came as no surprise to discover later the well-documented correlation between an oversized logo and a high level of insecurity. Today I still have a few Aeronautica shirts hanging in my closet—an attempt, no doubt, to hang onto my own Twin Self, in this case, a kid who craved a shirt he wasn’t able to buy.

The third brand? Royal Copenhagen, an elegant porcelain brand founded in 1775, whose debut collection included plates and bowls for the Danish royal family. Most families with children living in Denmark during the 1970s, ’80s and ’90s, including my own parents, owned one or two pieces of Royal Copenhagen china with its signature blue, handcrafted lines. Growing up, I associated the brand with high-end restaurants, royalty, heritage and tradition. Later, when I could afford to, one of the first things I did was to buy a set of Royal Copenhagen plates. Why? Subconsciously, I can’t help but think I wanted to “complete” my life in a way my parents never could. By buying Royal Copenhagen in a culture governed by Janteloven, the Scandinavian moratorium against standing out, maybe I was also telling the culture I had succeeded in my life—that I was someone. It was a moment when I realized the degree to which brands fill in the missing holes of our identities, whether we acknowledge it or not.

Along with a well-cut suit and a necktie, a luxury watch is almost mandatory in the business world, and I eventually allowed a fourth brand, Rolex, to “say” something about myself. One day, when I was at a meeting, flashing around my Rolex, I noticed a well-dressed older man studying my watch intently. He seemed bemused rather than impressed. Finally he approached me. He couldn’t help but notice my watch; in his experience, only Russians and Chinese wore Rolexes as conspicuous as mine. Also, was I at all aware I was wearing the women’s model? No, I said, ashamed, I wasn’t. Twenty-four hours earlier, my Rolex had been my proudest possession. Now I was mortified. I ended up giving it away and buying the “right” one, which I still wear today.

Along with the Rolex, for years I also carried around an American Express Centurion Card, known as “the Black Card.” I told myself I’d chosen the card because of its functional benefits, including a concierge and travel agent, personal shoppers at Saks and Gucci, and assorted worldwide hotel privileges, when in fact I was seduced by its emotional appeals. Three or four years ago, when American Express told me they weren’t willing to honor the points I’d accumulated over the years, I let my membership go. I replaced my Amex with a Visa that offered more than double the points. Yet I still felt a huge sense of loss. What had I just given up? Status. Belonging. The feeling that I was special. What would merchants, waiters, hotel clerks and my friends say when I took out my Visa? The answer: nothing. They wouldn’t notice. The validation and worth the Amex Black Card had given me was suddenly very obvious.

The brands we like, and buy, and surround ourselves with—and by now you know I define a “brand” as anything from the music on our playlists to our shoes, to our sheets, to our toothpaste, to the artwork hanging on our walls—have the profoundest possible things to say about who we are. As brands, our professional job titles are really no different. For example, over the years many people have come to me for job advice. Should they quit their job at the Fortune 100 company and launch a consultancy out of their home? Lost in all the talk about salary, benefits and commuting time are the emotional consequences of a job change, or the vulnerability the people are liable to feel once the logos on their business cards are gone.

The fear of losing their “branded” identities is as good an explanation as any to me why CEOs and senior executives spend almost no time at all in their own stores or interact with the consumers who keep them in business by buying their razors, sodas, seafood, shirts, granola, frozen foods, perfumes and pharmaceuticals. Even executives who participate in focus groups observe the proceedings behind one-way mirrors, in air-conditioned rooms equipped with snacks, cold drinks, monitors and mute buttons. What they miss, again and again, are those moments when they might uncover something new and valuable about themselves or their brand.

In some instances, I’ve found that executives don’t even use their own products. A case in point was Ansell, the world’s second-largest manufacturer of medical and industrial gloves and condoms. Recently, Ansell’s executive team invited me to speak at the company’s annual retreat in Sri Lanka, the headquarters of all Ansell’s condom production, to discuss “the future of condoms.” As I entered the room, I noticed that most of the executives were in their 40s, 50s and 60s. This was striking only to the extent that Ansell is in the business of making and selling condoms, a product generally favored by a younger demographic. It soon became obvious that everyone there was accustomed to using standard, clinical descriptions of their product, like “prophylactic” and “protective solutions.” That’s when I told the room we were going to carry out a small experiment. I handed out a condom to everyone in the audience, and then switched off the overhead lights. “We’re now going to do something you’ve never done before,” I said. “It’s sex time! With no lights on!” and I asked people to open their condoms.

I hadn’t intended to shock anyone, but it was obvious I had. I heard a lot of crackling and rustling in the darkness as Ansell executives and employees attempted to tear open the package’s double seal. When I turned the lights back on a minute later, not a single person in the audience had managed to open the package—in conditions that duplicated how most consumers access condoms.

This is why I do everything I can to ensure that company executives experience their stores—and products—in the same way consumers do. During my interactions with Tesco, the British multinational grocery retailer, the CEO introduced “Mission Feet on the Floor,” a program in which every executive was required to work on the floor of one of its grocery stores for several days at a time. To help them understand how Tesco’s food tasted compared to its rivals, executives were also invited to an offsite location and asked to prepare and cook all of Tesco’s premade sandwiches, salads and hamburgers, as well as the foods of their competitors. In Colombia, I once consulted for a bank chain notorious for its slow customer service and long lines. I asked bank officials to pretend they were customers. It was an exercise in frustration, and even rage. Some executives waited up to an hour in line, while others were punted from teller to teller in order to secure a simple signature. When it was time to present my findings, I told the executive team that from now on we were implementing three new rules: No one should have to wait longer than three minutes for customer service; customers should be asked to sign a piece of paper only once; and there would always be a parking space available. A year later, it was the premier bank in South America for customer service.

Bear in mind that none of these examples had much, if anything, to do with big data, which can only take us so far. After all, humans dissemble, consciously or unconsciously. Most of us aren’t aware of our habits and desires. In a 2015 discussion at the Cannes Lions Festival between Tom Adamski, the CEO of Razorfish Global, and Will Sansom, director of content and strategy at Contagious Communications, Adamski went so far as to say that digital media, and big data, has contributed to a global decrease in brand loyalty. Why? In Adamski’s words: “Brands are not treating us as individuals . . . Brands are still relying on archaic—and quite frankly, flawed—segmentation processes that market to demographics. But they don’t market to me.”6

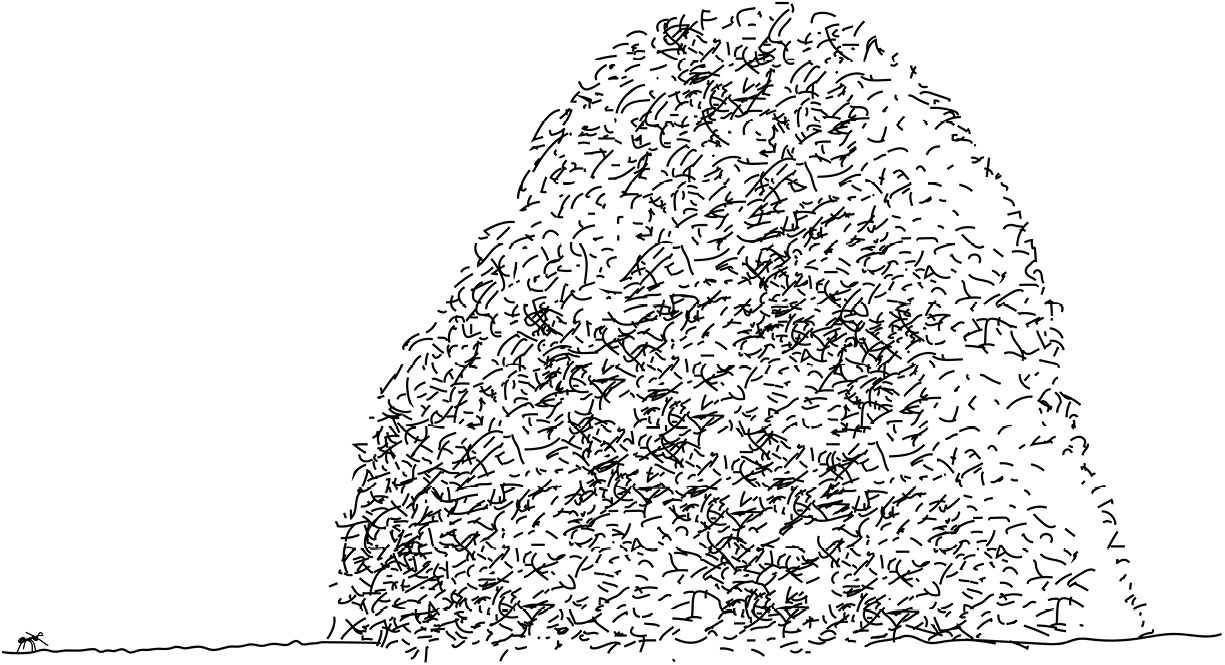

Big Data rarely helps to identify the “needle” in the stack

Illustration by Ole Kaarsberg

If companies want to understand consumers, big data offers a valuable, but incomplete, solution. I would argue that our contemporary preoccupation with digital data endangers high-quality insights and observations—and thus products and product solutions—and that for all the valuable insights big data provides, the Web remains a curated, idealized version of who we really are. Most illuminating to me is combining small data with big data by spending time in homes watching, listening, noticing and teasing out clues to what consumers really want. After all, at age 14 when LEGO first hired me, I was that consumer, a kid enamored with the company’s building blocks. By observing my own behavior, and that of my friends, I was able to give LEGO executives insights on their product and company that any number of quantitative surveys could not—just as, in sharp contrast to what big data was telling them, the observations of an 11-year-old German boy were able to help reverse LEGO’s slide into bankruptcy.

Intriguingly, we are now turning the tables on the Internet by circling back and finding human—not digital—insights about ourselves based on our own unconscious online behaviors.

In 2013, for example, using data accumulated from 250,000 people over a period of ten years, a study appeared in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology examining music consumption tastes as they evolve over the course of a lifetime. Music, it appears, adapts to whatever “life challenges” or psychosocial needs we face as we get older.7 The study divided music consumption patterns into five “empirically derived” categories dubbed the “MUSIC model”—an acronym that stands for mellow, unpretentious, sophisticated, intense and contemporary. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the first significant age of music-listening is adolescence, a time defined by intense, which possibly reflects increased hormonal activity or the creation of the teenaged “self.” Intense intersects with a rise of contemporary music, a trend that lasts until early middle age, when two other “preference dimensions”—Electronic and R&B—enter the mix, both of which are “romantic, emotionally positive and danceable.”8 The final musical age of humans is dominated by sophisticated—jazz and classical music—and unpretentious—country, folk and blues. These latter two musical forms are relaxing, positive and link indirectly to listeners’ social status and perceived intellect.9

What do the sports we love the most say about us? A study carried out by Mind Lab surveyed 2,000 UK adults and found that bicyclists are “laid back and calm” and less likely than runners or swimmers to be stressed or depressed. Runners tended to be extroverted, enjoyed being the center of attention and preferred “lively, upbeat music.” Swimmers, the study concluded, were charitable, happy and orderly, whereas walkers generally preferred their own company, didn’t like drawing attention to themselves and were comparatively unmaterialistic.10

Are you aware that people with a lot of Facebook friends tend to have lower-than-average self-esteem?11 Or that the more neurotic Facebook users are, the more likely they are to post mostly photos?12 Last year, an article in the New York Times Magazine analyzed the significance of the passwords we use to get online and access certain websites. The article reported that in the same way we leave a trail of emotional DNA in our wake, we also distill emotion inside our passwords—and that many of our passwords ritualize a regular encounter with a meaningful memory, or time in our lives, that we seldom have occasion to recall anywhere else. “Many of [our passwords] are suffused with pathos, mischief, sometimes even poetry. Often they have rich backstories. A motivational mantra, a swipe at the boss, a hidden shrine to a lost love, an inside joke with ourselves, a defining emotional scar—these keepsake passwords, as I came to call them, are like tchotchkes of our inner lives.”13

Big data might find it hard to find meaning, or relevance, in insights like these. In every study I mention there is a missing question: How might these findings be combined with small data to affect or transform a brand or business? Subtext Research might reveal that a 16-year-old girl who listens to “intense” music might find it a poor fit with her teenaged identity, and a 45-year-old Englishman who listens to John Coltrane and Chopin might tell you he pines for the intensity of his teenaged years and, in fact, wears a black rubber band around his wrist as a badge of rebellion. But you would never know this until you sat across from these people in their living rooms or bedrooms.

Nor, it seems, could an unnamed banking institution truly comprehend the behavior of its customers even after leveraging a big data analytics model designed to prevent customer “churn,” a term referring to customers who move money around, refinance their mortgages, or generally show signs they are on the verge of exiting the bank. Thanks to the analytics model, the bank soon found evidence of churn, and promptly drafted letters asking customers to reconsider. Before sending them out, though, the bank executive discovered something surprising. Yes, indeed, “big data” had seen evidence of churning. Thing is, it wasn’t because customers were dissatisfied with the bank or its customer service. No: most were getting a divorce, which explained why they were shifting around their assets.14 A parallel small data study could have figured this out in a day or less.

Then there are the issues facing Google’s new self-driving cars, most of which it seems can be credited to the mismatch between technology and humanity. According to the New York Times, last year as one of Google’s new cars approached a crosswalk, it did as it was supposed to and came to a complete stop. The pedestrian in front crossed the street safely, at which point the Google car was rammed from behind by a second non-Google automobile. Later, another self-driving Google car found that it wasn’t able to advance through a four-way stop, as its sensors were calibrated to wait for other drivers to make a complete stop, as opposed to inching continuously forward, which most did. Noted the Times, “Researchers in the fledgling field of autonomous vehicles say that one of the biggest challenges facing automated cars is blending them into a world in which humans don’t behave by the book.”15

As accurate, then, as big data can be while connecting millions of data points to generate correlations, big data is often compromised whenever humans act like, well, humans. As big data continues helping us cut corners and automate our lives, humans in turn will evolve simultaneously to address and pivot around the changes technology creates. Big data and small data are partners in a dance, a shared quest for balance.

Earlier, I wrote that despite the 7 billion or so people inhabiting the earth, in my experience there are only anywhere from 500 to 1,000 truly unique people in the world. This isn’t to put down individuality; instead, it recognizes the degrees of connectivity aligning humans who ultimately can be “divided” by four criteria: Climate, Rulership, Religion and Tradition.

Climate is only indirectly linked to the sun shining overhead, or whether or not your winters are cold or temperate. Rather, it refers to how your environment reflects and also influences behavior and diet. Scandinavian natives, for example, favor a diet weighted heavily toward richer, fattier foods, whereas the Mediterranean diet is lighter and more oil-based.

Rulership refers to the power, or government, in charge, whether it’s Vladimir Putin in Russia, a Democratic or Republican regime in the United States, the Communist Party in China, or the dictatorships of Iran, Jordan, Ethiopia, Sudan and elsewhere. How free are a country’s residents? Religion, of course, refers to the influence of belief in a country, how dominant or irrelevant it is, and whether a person’s belief system lies behind decision-making processes. Finally, Tradition focuses on a country’s unspoken protocols, whether it is the European habit to ignore other elevator passengers or the American predilection for friendliness. Once you’ve taken these four variables into account and set aside differences in class, race, skin color and gender, humans are the same no matter where they live.

Until recently, I never considered what I did for a living as a repeatable methodology. But over the past few years, nearly half-a-dozen companies have asked if I could distill my Subtext Research into a training program. In some segments of Nestlé, where I’ve consulted for years, my techniques, or Subtext Research methodology, have become an integral part of analyzing new products, ideas, innovations and brands. Today, thousands of Nestlé employees spend 48 hours a year visiting consumers in their homes.

I’m often asked the following question: What about sampling bias, where members of a population are unequally represented? With a smaller sample size, how can anyone, much less a company, hope to find a comprehensive solution or answer? If it does, is there any guarantee that your findings will accurately represent a larger whole?

My answer is that a single drop of blood contains data that reveals nearly a thousand different strains of virus. Providing that your sample size is well chosen, there is little difference between a blood sample and the work I do, which is why interviewing 50 respondents (rather than 5 million) is often more than adequate to carry out a solid 7C methodology. Harder for many people, and businesses, to admit is that rather than basing their research on millions of consumers, sometimes all it takes is ten people to transform a brand or business.

Working for Lowes, for example, I began my investigation with my own observations about American culture: the rounded shapes, the lack of physical touch and the homogenous retail landscape. I eventually connected these observations to a hypothesis, i.e., the high degree to which fear influenced American life. When I interviewed Trollbeads fans, one of the first things I picked up was how many of them said they missed the sense of community, family and collegiality they remembered as children and how, for many, Trollbeads was able to assemble a collection of highly personal memories that linked together the passing years.

In every case, something was missing from people’s lives: a subconscious desire. By identifying an unmet desire, you are that much closer to uncovering a gap that can be fulfilled with a new product, a new brand or a new business. Remember that every culture in the world is out of balance, or in some way exaggerated—and in that exaggeration lies desire.

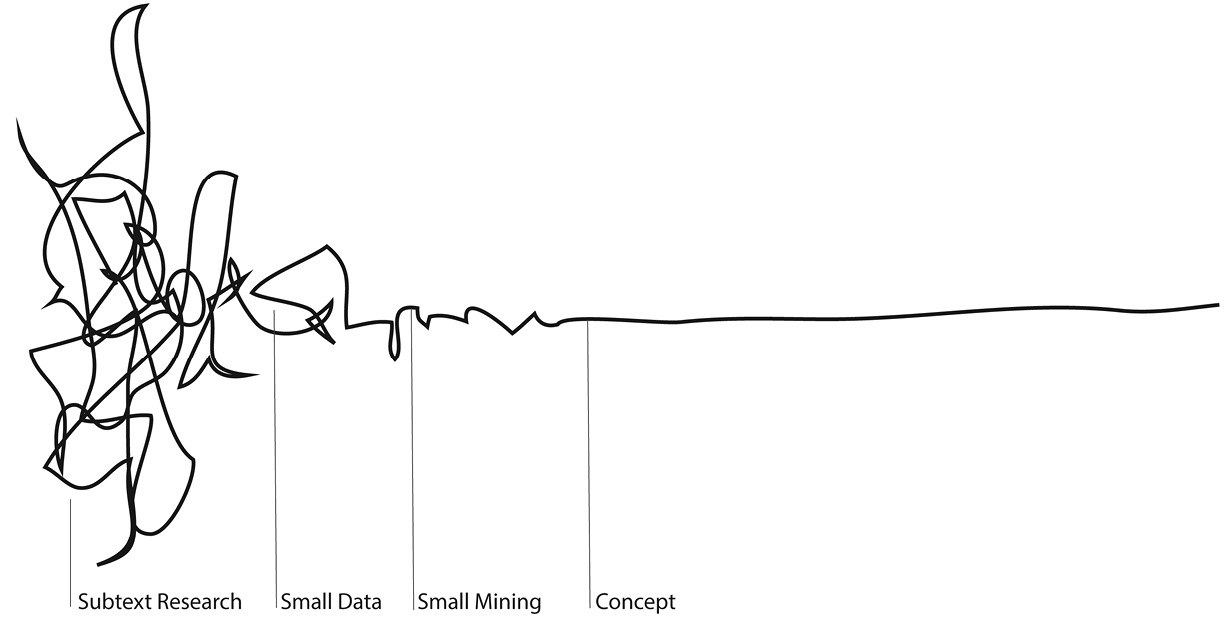

Subtext Research helps to identify Small Data, which in turn leads toward the creation of a Concept

Illustration by Ole Kaarsberg

The 7Cs in my Framework stand for Collecting, Clues, Connecting, Causation, Correlation, Compensation and Concept. Consider the following as a pocket guide to how to take one, or several, small pieces of small data—a refrigerator magnet, a porcelain frog—and very possibly transform them into a winning concept. Throughout this book you have been traveling the world with me on an airplane, bouncing from place to place, culture to culture. It’s time you came inside the cockpit.

Collecting, or, How are your observations translated inside a home?

The viral Internet dress photo is a good reminder that none of us sees the world in the same way. Most of us are blinded by the familiar. We surround ourselves with people who are like us, who believe the same things we do. Our Facebook newsfeeds are no different, reflecting our interests, beliefs, concerns and biases.

The first step in the 7C process, then, is to do everything you can to remove the filter that keeps you from seeing what is really going on. My advice? Get a haircut.

Let me explain. The “collecting” step begins with establishing navigation points, on both macro and micro levels. This includes getting perspectives from cultural observers, for example, people who are new to the area, either expats or people who see the community through objective eyes. Ask them: What does the neighborhood, or city, or town, look like and feel like? Are the sidewalks deserted? Are there children playing outside? Are people friendly? Do you ever feel scared, and if so, why? Is there any sense of neighborhood pride? If you see people on the streets, do they meet your eyes or look away? Is the garbage picked up regularly? What makes a city or town come together? What divides it? Why? Visiting Brazil, I quickly found out that the nation is preoccupied with football and religion, and divided by restrictive class levels. There was a tension implicit in these layers. Did Brazilians need to escape? This tentative hypothesis was one I would eventually shape and refine.

Now, seek out a hairdresser or one or several other “local observers” who can help you establish a baseline perspective, and who inhabit a more or less neutral space within a community. It doesn’t have to be a hairdresser; it could be a bartender, a mailman, or a church, community or sports club leader. Whoever it is, cultural and local observers are privy to information most people are not. They can tell you what’s really going on. They are more or less unbiased. They can also point you to their own networks of friends and acquaintances.

The navigation points you gather from local observers will help you to frame your initial observations and create a hypothesis before you enter a consumer’s home. In turn, your initial hypothesis will help you create “tracks,” or topics of interest or focus, to follow once you begin interviewing consumers. Only rarely will one of your first six tracks be the final one, and half of them will later be disproven or tossed away. Think of them as stepping-stones that lead to bigger and better stepping-stones that lead, finally, to a concept.

At this collecting stage, you are trying to capture as many different perspectives from as many trustworthy sources as possible. If you have any doubt whether these local observers are useful, or reliable, social media is a fast, easy way to confirm their degree of integration into a community. People active in social media are, by nature, extroverted and confident. Take notice of how often they post; their degree of curation; the relevance of their content; and whether or not there is a touch of swagger or exhibition to their postings—all of which combine to create an ideal local observer. Bear in mind that local observers often have both a public and a private Facebook profile, making it easier to contact them. During your preliminary phone call, by asking the same questions you asked of cultural observers, you can quickly discover if their perspectives are useful or not.

If you are working on behalf of an existing brand, I also recommend interviewing the brand’s past, current and potential future users—a group that ideally should reflect 50 percent of the total aggregate of respondents.

Clues, or, What are the distinctive emotional reflections you are observing?

Remember, you are an investigator whose goal is to create a narrative, a cohesive story that hangs together. For this reason, nothing you see or hear is irrelevant or wasted. Imagine that you are equipped with a hypothesis and entering someone’s home for the first time. (Your hypothesis may be true, half true or false—you don’t know yet.) Think of a residence as a place that is home to an infinite series of small voices that owners are broadcasting in every room. Are the voices congruent, or are they out of tune? What unconscious, seemingly random pieces of small data are hanging from the walls, hiding inside “off-limits” zones like the refrigerator and the kitchen cabinets? Everything in the home, from the art on the walls to the insides of bathroom cabinets, is positioned where it is for a reason.

Here, I regularly call upon a model to divide the assorted “selves” that make up the average consumer. First is the idealized self we project onto the world, the one focused around how we’d like others to see us (which, I might add, is often very different from who we actually are). This manicured, public self is similar to the one we assemble on our Facebook pages and Instagram accounts. Components that also fall under the category of “idealized self” are the objects we collect and display in our homes, from photographs to heirlooms to tchotchkes. Over the years, I’ve observed that our collections form a timeline of our lives, a secondary calendar that offers a valuable perspective on who we are—or believe we are—and where we’ve been. The most common “recharging station” for reflecting on what we have accumulated is the living room, and for adolescents, backpacks and laptop covers.

That said, the places where our idealized selves conflict with our actual selves tend to be private: our refrigerators, kitchen cabinets, wardrobes and—in the case of men—garages and online folders.

Often, it is what is missing that forms the cornerstone of a successful hypothesis. Take Denmark, for example, with its countless “conversation kitchens” and untouched, unused Brio tracks. On the surface, most Danish homes are “perfect” in appearance. Get closer, and you will realize that room after room is, in fact, staged, and the country’s stress levels are among the highest in the world. Relatedly, take note of a small symbol that may, in fact, overwhelm every other clue. In a small residence inside a Brazilian favela, I saw a flower in a cup inside a beer can on a shelf. In a gritty environment, it stood out as a badge of hope.

As LEGO found out more than a decade ago, the question “What are you most proud of?” can yield surprising and transformative answers. It could be an old guitar; a handmade quilt; a contemporary painting; a set of vintage wineglasses. Ask respondents if you can look through old photo albums or iPhoto collections. Explore the refrigerator and the kitchen and bathroom cupboards before moving into the bedroom and the bedroom closets. Determine how people want to be perceived by the rest of the world by asking them to show you their favorite piece of clothing. Determine the age of their Twin Self by paying close attention to the musical playlists on their smartphones, computers or streaming music services. Do they subscribe to any iTunes television shows or movies? If applicable, what films and TV shows are in their Netflix queues? (In this way, you can determine their shared cultural references.) What evokes the strongest emotion in them? Is it pride? Is it the memory of a loved one? Is it a pet? Is it a child? Finally, I ask people to answer two questions: What is most important in your life? and What worries you the most?

Don’t be discouraged if at first you don’t find what you are looking for. Such is the nature—even the definition—of detective work.

Connecting, or, What are the consequences of the emotional behavior?

By now, you probably have half-a-dozen or more pieces of small data in front of you. You may find yourself, as I did with Lowes, in a culture that prohibits touching, and whose downtowns empty out at 5 p.m. every afternoon and where there is a striking absence of community and belonging. In the case of Trollbeads, by this point I had discovered that the brand’s fans were aware something was missing from their lives; and that consumers attracted to Roombas were staging their homes using a technological gadget as a conversation piece.

Ask yourself: Are there any similarities among the clues you have accumulated? Are the clues beginning to tilt in one direction? If you had one, are you beginning to validate your initial hypothesis?

Remember that a clue might be physical (an extravagantly patterned shirt that doesn’t fit with the rest of a respondent’s wardrobe) or emotional (a respondent is obsessed with U2). You are seeking an emotional gap—too much or too little of something. As is the case with many homes in Denmark, if you enter a home where nothing is out of context, you know you’ve struck gold. If you are on the right track, the body language of respondents will often show unease or outright discomfort, in which case you will know you are onto something.

The next step is to Small Mine—distill and analyze—the clues you’ve accumulated

Illustration by Ole Kaarsberg

Causation, or What emotion does it evoke?

For Lowes customers, the routines of their lives had become a self-fulfilling prophecy. Trollbeads consumers were experiencing a sense of deep insecurity, whereas Roomba customers found the product a way to fill a vacuum of loneliness and insecurity. It’s now time to gather your findings in your office or place of work, and begin the process of Small Mining.

Generally, I mount a time line consisting of photographs and observations on a large bulletin board. It is here that your wall reflects the emotional DNA that you have found, as well as the correlations you’ve identified along the way. Place all these observations and photographs together and seek out the commonalities.

Ask yourself, “What emotion will this evoke in a human being?”

At this point, it’s essential to put yourself in the shoes of respondents. If you were he or she, how would you feel? What would you want? This isn’t a particularly easy question to answer, especially in cultures alien from our own. If it is too challenging, it might be a good time to call, or revisit, the cultural or local observers you interviewed before beginning the clue-gathering process. Present your observations to them. Ask them what they think.

Correlation, or, When did the behavior or emotion first appear?

In the correlation stage, we seek evidence of a shift, or change in a consumer’s behavior, otherwise known as an entry point. When did this change take place? Did it happen when she got married? When she had her first child? When she got divorced? An entry point, or personality shift, can be expressed via clothing, or by adopting a new set of friends, getting (or losing) a partner, sending children off to college or any other major milestone or career transition.

As I wrote earlier, we are too close to ourselves to observe what is familiar. For this reason, often during the Small Mining process, we need to reset our own perspective by reaching out to one of the respondent’s friends or family members. Contact this person so that he or she can help validate, or add to, your thinking during the latter part of the interview.

Compensation, or, What is the unmet or unfulfilled desire?

Having found evidence of a shift, it’s now time to distill it to its most emotional essence: desire. What is the desire that is not being fulfilled? What is the best way to fulfill it? With Lowes, the answer was to create a strong sense of belonging within a physical setting. Trollbeads fans needed to reconnect and rediscover what it felt like to belong to a group; and Roomba fans needed a way to show the world their humanity.

Often, by poring through people’s photo albums, you will find the answer. As you review the pages, look for the happiest moments in people’s lives. Use them as reflections of a time, or a moment, when people felt most in harmony, on top, at peace and emotionally fulfilled.

Inside these two poles—where people felt emotionally fulfilled versus where they are right now in their lives—is where you will find desire. Does the desire you have identified complement the cultural and local observations, as well as the clues you observed inside respondents’ homes?

Concept, or, What is the “big idea” compensation for the consumer desire you have identified?

Take your observations home and mull them over. As I wrote earlier, my best ideas come as a result of swimming laps in hotel pools. I fundamentally believe that “creativity” involves combining two ordinary things in a completely novel way. LEGO Mindstorms—the company’s brand of customizable robots—involved merging LEGO building blocks with a computer chip. Uber involved combining a private car service with a social media network. In my own work, Lowes 2.0 came as the result of combining a supermarket with entertainment and community, while Tally Weijl 2.0 mixed and matched social media with the traditional dressing room.

Ideas, remember, are less likely to germinate under pressure. They come together when we least expect them. So swim, bike, garden, walk along the sand.

I’m often reminded of the most memorable interview I have ever conducted. The reason it was so revealing, I realized later, was that I got the time of our appointment wrong and showed up an hour before I was supposed to. When I rang the doorbell, the respondent, a middle-aged woman, greeted me at the door. She had just gotten out of bed, her hair was uncombed and she was wearing a loose blue bathrobe. She didn’t look at all pleased to see me. I apologized repeatedly for getting the time wrong, and told her I would come back in an hour, but she insisted I come in anyway.

What followed was the most honest interview I’ve ever conducted. The woman had had no time to get ready. She’d had no time to prepare her face, or clean her house. I was seeing her, for all intents and purposes, naked. Accordingly, there was no point in deception, no point in telling me what she assumed I wanted to hear. Two hours later, I left her house reminded of the sheer hours of our lives we spend putting on masks to greet the world.

Based on the findings of a recent qualitative survey carried out in Switzerland, in fact, most of us have up to ten discreet interdependent social identities—identities, the study concludes, which are often in conflict.16 Let’s imagine a middle-aged bank teller living in Pensacola, Florida. He is a father, a son and a husband. He is a Floridian. He is a bank employee. He is also a bicyclist and a recreational runner, and at night, drinking with his friends, he is “the funny one.” He is also a vegetarian, an amateur guitarist, and on weekends he helps coach soccer at his daughter’s high school. Then there are his online identities, including his Facebook, Twitter and Instagram selves. Most surprising is that the man’s ethical mind-set, honesty, sociability and even level of social engagement changes from personality to personality. Imagine that in his professional role, for example, he may be primed to dissembling, or outright deceit, while simultaneously, as a dad, he finds dishonesty repellent. My role—the role of anyone trying to make sense out of small data—is to understand not just one single personality, but all of them.

Which is why in the end the secret behind any ethnographic research will never be found in any methodology, even mine. It begins with yourself. Who are you? What are you like when you’re by yourself? When you post a status update on Facebook, or “like” a piece of music, what are you telling the world about yourself? When you buy a pair of pants, or a new brand of shoes, when you hang a set of bamboo curtains across your window or cherry-pick photographs to tack onto your refrigerator, or leave out a bottle of facial moisturizer in your bathroom, what are you communicating? In our small data, now and forever, lies the greatest evidence of who we are and what we desire, even if, as LEGO executives found out more than a decade ago, it’s a pair of old Adidas sneakers with worn-down heels.