The Sand Creek Massacre site is now on land owned by a Colorado rancher named Bill Dawson—or at least it is unless he’s recently sold his holdings. The site is just north of the hamlet of Chivington, Colorado: the town is named, of course, for John Milton Chivington, the man who planned and led the massacre.

The Arkansas River is a little distance to the south, flowing through expensive irrigated agricultural country. Not far upriver is the reconstructed Bent’s Fort; it had been the first great trading post on the Santa Fe Trail, visited by everybody who traveled this famous trail. William Bent, who, with his brother Charles and the trader Ceran St. Vrain, built the original fort, which had initially been farther west, had a number of half-breed children by two Cheyenne sisters: first Owl Woman, who died, and then Yellow Woman.

At least four of William Bent’s children were camped with their Cheyenne cousins on the day of the Sand Creek attack: Robert, George, Charles, and John. What happened that day turned one of these sons—Charles—into a half-crazed, white-hating Dog Soldier, a torturer and killer who at one point even went south meaning to kill his own father. Fortunately William Bent was away at the time.

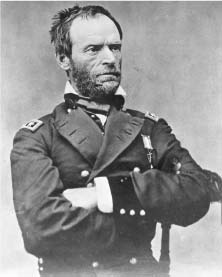

William Bent

Bill Dawson, the rancher who owns the land where the massacre occurred, is, by all accounts, a reasonable and likable man who, while holding his own views on Sand Creek, has nonetheless been generous with Indian groups who want to hold prayer services there. In the 1990s he allowed Connie Buffalo, an Ojibwa woman who had come into possession of two scalps taken at Sand Creek to bury them at the site, with appropriate ceremonials. Connie Buffalo had been given the scalps by the owner of a small motel near the site. They had been in the man’s family for years but the owner seemed to feel that Connie Buffalo had a better right to them: he offered them to her with tears in his eyes.

I mention this exchange because it suggests that the power of such an event as Sand Creek resonates through time as few other experiences do. Southeastern Colorado, like much of the Great Plains, is very thinly populated now. There are not many people there, but most of the farmers and ranchers who operate near the site had been in that place for a long time. Sand Creek, whether they like it or not, has always been in their lives. Some might still argue for Chivington’s position, but few doubt that the tragedy marked their families and their region. Few, I imagine, see it as a simple case of white wrong. Though it was wrong, it had a context that few not of that region can appreciate now.

I would agree with the locals that Sand Creek wasn’t simple. Perhaps the plainest thing about it was the character of John Chivington, who, though a longtime Free-Soiler, was also a racist Indian-hater. But Chivington was not the only man shooting Indians that day and Sand Creek was not an entirely spontaneous eruption of violence, in which some hotheads in Denver decided to attack a camp of one hundred percent peaceful Indians.

When I visited Sand Creek, the best I could do without bothering Mr. Dawson was to drive around it in a kind of box route, on dirt roads. From several rises I could see where the massacre took place. On much of my box route I was trailed by an SUV from Michigan—its occupants no doubt hoped I would lead them to this historic place. I couldn’t, and they finally drove off down the road toward Kansas, which is not far away.

The country around the site is rolling prairie—very, very empty. From several modest elevations I could see the line of trees where the fighting took place. The plain is immense here; on a chill gray day the word “bleak” comes naturally to mind. “Pitiless” is another word that would apply. On a fine sunny day the plains country of eastern Colorado looks beautiful, but Sand Creek and Wounded Knee were winter massacres; the cold no doubt increased the sense of pitilessness. If you were at Sand Creek, being massacred and desiring to run, only the creek itself offered any hope. Otherwise, north, south, east, or west was only open country: totally open.

* * *

The first factor that might be noted in a discussion of Sand Creek is the date: 1864. The Civil War was in progress, a fact of some importance, as we will see.

More important, though, was that at this date the Plains Indians, from Kiowa and Comanche in the south, north through the lands of Arapaho, Pawnee, southern Cheyenne, and the seven branches of the Sioux, were unbroken and undefeated peoples. All were still able, and very determined, to wage a vigorous defense of their hunting grounds and their way of life. Up to this point what they mainly had to worry about in regard to the whites was their diseases, smallpox particularly. Though there had been, by this point, many skirmishes between red man and white, there had been only one or two serious battles.

The first major conflict occurred about a decade before Sand Creek, at Fort Laramie. The U.S. government called an enormous powwow, in which the various Indian tribes were to be granted annuities if they would agree not to molest the growing numbers of immigrants pouring west along the Platte—what we call the Oregon Trail. The natives called it the Holy Road.

The expectations the government nursed about this hopeful arrangement were wholly unrealistic—it involved a major misunderstanding of Native American leadership structures. No Indian leader had authority over even his own band such as a white executive might possess. No Indian leader was a boss in the sense that General Grant was a boss. And, all Indian leaders had trouble with their young warriors, who would run off and raid.

But few whites recognized these realities at the big gathering in 1854.

Shortly after this great powwow a foolish and arrogant young officer named Grattan took the part of a Mormon immigrant who claimed that a Sioux named High Forehead had killed one of his cows—a crippled cow, it may have been; it may even have been an ox.

High Forehead belonged to the Brulé Sioux, the branch then led by a reasonable chief named Conquering Bear, who at once offered to make restitution for the cow. He may even have offered the Mormon a couple of horses; but Grattan insisted on High Forehead’s arrest. Conquering Bear pointed out that High Forehead was a free Sioux: he himself had no authority to order an arrest.

At this point Grattan, determined not to lose face, shot off a small field piece, killing Conquering Bear, something even Grattan probably had not meant to do. The Sioux then immediately killed Grattan and thirty of his soldiers, including the fort’s interpreter, who may have contributed to the disaster by exceptionally sloppy translation. The Sioux could probably have destroyed the Fort Laramie garrison at that point, but they chose, instead, to take their dying chief and melt away.

About a year later the army mounted a punitive expedition led by General William Harney, who went north and attacked a band led by Little Thunder, who had not been involved in the trouble at Fort Laramie. General Harney too had field pieces, and used them to slaughter many Sioux—about ninety, some say, an enormous loss for the Indians. This may have been the battle that showed these Western tribes the true killing power of the whites. Crazy Horse may have witnessed this slaughter and decided as a result to have nothing to do with white men, other than to kill them.

A second large-scale conflict prior to Sand Creek was the Great Sioux Uprising in Minnesota in 1862, a conflict that occurred because the Sioux in southeastern Minnesota were being systematically starved by corrupt Indian agents who refused to release food that they actually had in hand. The rebellion led by Little Crow was so fiercely fought and had so many victims on both sides that for a time it retarded emigration into that part of the country. The Indians were eventually defeated, but not before they killed many whites and brought terror to the prairies. When it was over the whites prepared to hang three hundred Indians, but Abraham Lincoln took time out from his war duties to study the individual files, reducing the number hanged to about thirty.

Little Crow

If one considers the Plains Indians as they were in 1864—a mere twelve years before the Little Bighorn—they constituted a formidable group of warrior societies, all of them naturally more and more disturbed by the numbers of white people who surged across their territory, disrupting the hunting patterns upon which their subsistence depended.

In Colorado, where Sand Creek happened, emigration soared in the 1850s because of gold discoveries in the Colorado Rockies. This brought many thousands of people into the region in only a few years, and yet the Indians tolerated this great wave of whites pretty well at first. Denver was organized as a town in 1858; it was a rough community from the start, and its physical situation, at the very base of the Rockies, meant that it could only be reached from the east by crossing a vast plain; the natural terrain offered little protection. On that plain, in 1858, grazed millions of buffalo, the support of the nomadic warrior societies mentioned above. Soon freight routes across the prairie bisected the great herds and eventually more or less split them into northern and southern populations. The emigrants came in all sizes and shapes; there were large freight convoys bringing in much needed goods and equipment, but there were also single families traveling alone, struggling across the great emptiness in hopes of finding somewhere a bit of land where they could sustain themselves. If the 1850s were largely quiet, with neither the Indians nor the immigrants knowing quite what to make of each other, by the early 1860s Indian patience had begun to wear thin.

There began to be attacks, sometimes on a few soldiers, more often on the poorly defended immigrant families. From around 1862 on, immigrant parties that happened to run into Indians were apt to be roughly treated, the men killed and mutilated, the women kidnapped, raped, butchered. The meat shop attitude had clearly arrived on the Great Plains. The government built forts, here and there, but these the Indians could easily avoid. The forts offered little protection to the widely scattered immigrant parties.

Pioneering during this period was always a gamble, no matter which route one took across the plains. By the early 1860s all routes into Denver from the east were dangerous. Hundreds of miles of plain had to be crossed, with the immigrants vulnerable to attack all the way. But the westering force was irresistible in those years and the immigrants kept coming.

In Denver, every time a wagon train or immigrant family got wiped out, local temperatures rose. Apprehension, which I have earlier suggested as a factor in several massacres, became acute in Colorado during the first years of the 1860s. In the little towns and even in Denver women were oppressed by fears of kidnapping and rape. Every depredation got fulsomely reported. One captured woman, after a night of rape, managed to hang herself from a lodgepole; others survived to endure repeated assault and, in some cases, eventually escaped to report details of their ordeals.

John Milton Chivington was a Methodist preacher from Ohio. In New Mexico, at the Battle of Glorieta Pass, he became a Union hero by flanking a force of Confederates who had moved up from Texas; the Confederates lost most of their supplies and were forced into ignominious retreat. A major at the time, Chivington was made colonel and soon brought the authority of a military hero into the bitter struggle with the Plains Indians.

Some historians argue that the Confederates skillfully exploited the hatred of the plains tribes in order to increase pressure on Union troops. It is certainly true that in Oklahoma the Five Civilized Tribes, or such of them as had survived the Trail of Tears, fought mostly with the Confederates. The famous Cherokee general Stand Watie was, I believe, the last Confederate officer to surrender, which he did on June 23, 1865, well after Lee had had his talk with Grant.

No doubt there had been some deliberate provocation by the Confederates in Texas and New Mexico, but it’s hard to believe that many of the Plains Indians much cared which side won this white man’s war. What kept them stirred up was the whites’ rapid invasion of their country.

In the decade following the Fort Laramie conference an ever-increasing number of smart Indian leaders saw very clearly the handwriting on the wall. Many of these had been taken to Washington and New York; they had seen with their own eyes the limitless numbers of the whites, and the extent of their military equipment. Many of these leaders came to favor peace, since the alternative was clearly going to be destruction. The problem was that even if Black Kettle—who led the band attacked at Sand Creek—strongly favored peace, that didn’t mean he could then exercise full control of his warriors. Leadership among the plains tribes was collective but never coercive. Black Kettle and other leaders commanded a good deal of respect but it didn’t gain them much control. Warrior societies, after all, encouraged aggressive, warlike action. Raiding, for the young men, was more than a sport: it was how they proved themselves.

In the late summer of 1864, some two months before Sand Creek, the army and the Colorado authorities organized a council in an attempt to arrive at some kind of peace policy that might work. If the various tribes could endorse such a plan, and if they kept their word, they would be promised protection from attack. The peace Indians could even be given some token—a medal, a certificate, even an American flag, which would enable soldiers to distinguish them from hostiles while on patrol.

This ill-formed policy only increased the confusion, and there had been plenty of confusion already. Many bands were eager to become peace Indians and get their medals, irrespective of whether they seriously intended to stop raiding.

At one time not long after the conference it was rumored that six thousand Indians were on their way to Fort Lyon to sign up for the new program. No doubt the figure was wildly inflated. Even six hundred Indians would have swamped Fort Lyon and exhausted the supply of medals, if there were any medals.

John Chivington attended this strange council, which he regarded, not unjustly, to be a fraud and a sham. Black Kettle and a number of other chiefs readily acknowledged that there was likely to be a problem with the young warriors, besides which there were the Dog Soldiers, renegades from many bands who saw themselves as defenders of the old ways—they intended to keep fighting no matter what. Bull Bear, a leading dissident, attended the council but was so disgusted by what he heard that he stormed out, vowing to fight on—he fought on, and died at Sand Creek.

Bull Bear

Of all the leaders of the southern Cheyenne, Black Kettle seemed the most sincere in his determination to live in peace with the whites. In fact he was sincere to the point of naïveté. He had been given an American flag in 1861 and had acquired a white flag as well, both of which he waved frantically to no effect as Chivington and his men rode down on the camp.

In the weeks before Sand Creek, the routes into Denver came under increasing pressure from roving bands of Indians, and every attack or small conflict merely strengthened Chivington’s hand. Soon enough, with Governor John Evans’s consent, a poster was printed asking for volunteers to fight the Indians. The volunteers were to serve for one hundred days—Chivington easily raised a sizable force, but, in casting his net wide, he took with him a number of men, such as young Captain Silas Soule, who were not convinced of the necessity of the proceedings. Several such men were opposed to massacre as a method of control. Some of the men, particularly those under Silas Soule, refused to fire when the time came: some, including Soule, testified against Chivington in the rather unhelpful inquiries following the massacre.

Silas Soule

Even so, Chivington had plenty of firepower and an abundance of converts. He was six foot four and his towering presence easily cowed such waverers as dared to question the operation. Chivington was no coward. Twice in his career as a fire-breathing minister he had faced down formidable opposition, sometimes preaching with a loaded revolver on both sides of his pulpit. The congregation’s objection was probably to his Free-Soil, antislavery belief, convictions that are to his credit and which he never abandoned.

Just as intensely as he longed to free the slaves, Chivington also longed to exterminate the Indians, even unto the women and children. Well before Sand Creek he had been quoted as saying “Nits breed lice.” General Sherman, for a time at least, shared this view. And in fact no effort was made to spare the women and children at Sand Creek, at least not by the troops operating directly under Chivington’s command.

General William Tecumseh Sherman

As with all massacres, there are puzzling lacunae in the many narratives of the survivors. How far from Sand Creek was Fort Lyon, from which the expedition set out at 8:00 P.M. on the evening of November 28? Some thought it was forty miles, some thought thirty, and others said merely “a few.”

The vast company troop, somewhere between seven hundred and one thousand men, left the fort under cover of darkness, so that their movements would not be detected. Of course, had there been any Indians in the vicinity who were not stone-deaf they would not have needed to see much to know that a large body of men was on the move. The troops were traveling with artillery, which by itself would have made a good deal of clatter. The fact that, however far they came, they were in position above Black Kettle’s camp at dawn on the 29th suggests that they pressed on at a good clip through the night.

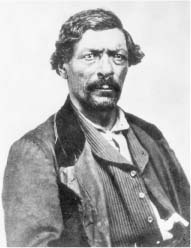

Jim Beckwourth

Controversy lingers about the scouts that led Chivington and his men across that darkling plain. One was the half-breed scout Jack Smith, who so ran afoul of Chivington that he was executed after the battle. Another was the old mountain man Jim Beckwourth, who lived to testify against Chivington at the inquiry; whether he witnessed the whole battle is disputed. And there was Robert Bent, son of William, who, some think, was forced to lead Chivington to the camp. If so Robert Bent must have been quite uncomfortable with what was happening, since he knew that various of his siblings were likely to be in the camp. All the Bents survived, though George received an ugly wound in the hip.

In the first predawn moments when the troops began thundering toward the camp, some of the Cheyenne women thought a buffalo herd must be nearby. They soon learned better. Chivington and the troopers always maintained that a Cheyenne fired first; if so, it was a lonely effort. About two-thirds of the Cheyenne in camp were women and children—there were perhaps fifty or sixty warriors. What saved the survivors were the steep creek banks, in which the fighters among the Cheyenne at once began to dig shallow rifle pits. The steepness of the banks enabled some to flee southeastward without exposing themselves to a fusillade from the troops. That the surprised Cheyenne managed to put up any resistance at all is a testament to their fighting spirit. Not for nothing did George Bird Grinell call them the “fighting Cheyenne.”

Young Captain Silas Soule immediately infuriated Chivington by refusing to order his men to fire; he even briefly interposed his troops between the Indians and the volunteers. Some say the ensuing battle lasted from dawn until mid-afternoon; others say the mopping-up operation continued all day. The few warriors who survived the first assault dug their rifle pits deeper and fought bravely to cover the retreat of those who fled beneath the creek banks. Black Kettle’s wife was shot nine times, and yet, when darkness fell, he carried her to Fort Lyon, where the doctors saved her.

Various stories from this battle exist in so many versions that they have become tropes. One involved a little Indian boy who stood watching the soldiers. One volunteer shot at him but missed; a second volunteer announced that he would “hit the little son-of-a-bitch,” but he too missed. A third took up the challenge: he didn’t miss.

Another often-told story involved a wounded Indian woman who held up her arms beseechingly, hoping to be spared; but, like the old, bloody-eyed woman in the Odessa Steps sequence of Battleship Potemkin, she was hacked down.

The Cheyenne fought gallantly, well into the afternoon—a few of the warriors managed to slip away. When the firing tapered off, the looting began. As at Mountain Meadows, fingers and ears were lopped off, to be stripped of rings and ornaments. Almost every corpse was scalped and many were sexually mutilated. A kind of speciality of Sand Creek was the cutting out of female pudenda, to be dried and used as hatbands.

Chivington and his men returned to Denver, to celebrity and wild acclaim. The scalps—one hundred in number—were exhibited in a Denver theater. Chivington, very much the hero of the hour, claimed to have wiped out the camp.

In fact, though, quite a few Cheyenne and Arapaho survived Sand Creek, including all of William Bent’s sons. The Indians hurried off to tell the story to other tribes, while the one-hundred-day volunteers celebrated.

Chivington’s most fervent admirer, Colonel George Shoop, confidently announced that Sand Creek had taken care of the Indian problem on the Great Plains—his comment was the prairie equivalent of Neville Chamberlain’s famous “peace in our time” speech, after Hitler had outpointed him at Munich. Shoop was every bit as wrong as Chamberlain. Sand Creek, far from persuading the Indians that they should behave, immediately set the prairies ablaze.

It sparked the outrage among the Indian people that led inevitably to Fetterman and the Little Bighorn. The Indians immediately launched an attack against the big freighting station at Julesburg, in northeastern Colorado. But for another blown ambush by the young braves, they might have wiped out the station. As it was, they killed about forty men. The trails into Denver that had been dangerous enough before Sand Greek became hugely more dangerous.

In the twelve years between Sand Creek and the Little Bighorn there were many pitched battles. Some, like Custer’s attack on the Washita in 1868, in which Black Kettle and his tough wife were finally killed, went to the whites; others, such as Fetter-man or the Battle of the Rosebud, went to the Indians. All up and down the prairies, from the Adobe Walls fight in Texas to Platte Bridge in Wyoming, a real war was now in progress. Charles Bent became one of the most feared of all Dog Soldiers, killing and torturing any whites he could catch.

In Denver, Chivington’s account of the raid did not go long un-challenged. In this case the power of the dead began to make itself felt almost at once. Stories soon seeped out about the terrible mutilations of women and children. People who had fully approved the attack—people tired of apprehension, of being afraid even to venture out of town for a picnic, were nonetheless troubled by some of the horrors they heard about. Stories about mutilated children—despite the “nits breed lice” doctrine—did not play as well as they had at first.

Reports that the Indians hadn’t wanted to fight were shouted down by the Chivington mob, but they kept leaking out. The carnage began to sit heavily on certain consciences, as it usually does after massacres. There had been a few soldiers, like Silas Soule, who refused to shoot down helpless Indian women or their children; in time some of them expressed their disgust at the proceedings. Chivington’s supporters were well in the majority, but there was a substantial minority opinion and it did get expressed.

Even as the battle began there had been doubters who informed Chivington that the Indians were trying to surrender; but he brushed this aside. He did not want to hear from Indian sympathizers and was not pleased by the least equivocation on the part of his militia. He had gone on a mission of vengeance and he made no bones about that fact. He frequently reminded the soldiers of what had been done to white women in the recent raids, and he succeeded well enough in keeping most of his troops stirred up.

But even Chivington, forceful as he was, did not succeed in banishing all doubt, all regret. The field of battle was one thing; a formal court of inquiry quite another. The formality inherent in even such a crude judicial procedure is about as far as civilized man gets from the dust, smoke, noise, and blood of a battlefield.

The inquiry was ordered by Congress. Once it got underway, Chivington objected to almost every question that was asked. With his towering presence and his power of denunciation he could intimidate many witnesses, but not all witnesses. Silas Soule held his ground and yielded nothing to Chivington’s bluster; the preacher made little headway with old Jim Beckwourth either. In the East the greatly respected General Grant gave it as his opinion that what happened at Sand Creek had been nothing more than murder. (He was equally blunt about what happened at the Little Bighorn twelve years later, declaring at once that the tragedy was Custer’s fault, a judgment that cannot have pleased the grieving Libbie Custer.)

Despite Chivington’s resistance, the commission of inquiry made it clear that what happened at Sand Creek was an out-and-out massacre. Joseph Holt, the army’s judge advocate, called it “cowardly and cold blooded slaughter, sufficient to cover its perpetrators with indelible infamy and the face of every American with shame and indignation.”

In this the judge advocate clearly went too far, because there were plenty of American faces in Denver who expressed neither shame nor indignation. Neither Chivington nor Shoop was charged with anything; to have charged them at that moment in Denver would have led to civil insurrection.

In April 1865, three weeks after he had married, Silas Soule, the officer whose testimony had done Chivington the most harm, was assassinated while taking a stroll on a pleasant evening. His murderer was most likely a man named Squiers, who promptly fled to New Mexico. The army sent Lieutenant James Cannon to apprehend him, which Cannon accomplished without undue difficulty. Squiers was returned to Denver but escaped again and headed west. This time Lieutenant Cannon could not pursue him because Lieutenant Cannon had been found dead in his hotel room, probably poisoned. Squiers was never brought to trial.

The carnage and ambuscade on the prairies east of Denver did not stop. Julesburg was attacked a second time. Then the Civil War ended, a cessation that forced the military authorities to notice that there was a full-scale Indian revolt going on in the West, conducted by a goodly number of highly mobile and also highly motivated warriors who were, at this juncture, fully determined to prevent the whites from taking their land.

Through the long winding, up and down, of the Indian wars, John Chivington remained popular in Colorado. To the end of his life he defied his critics, declaring, over and over again, that he stood by Sand Creek. He was to have his trials and sorrows. His son drowned and his wife died, after which he quickly married his son’s young widow, who soon took herself home. There were allegations of abuse. Chivington moved to San Diego, but soon returned to Denver, where he became an undertaker and, eventually, the county coroner. He died in 1894, about thirty years after the attack that made him famous, or infamous.

* * *

More than one Western historian has defended Chivington, one being J. P. Dunn, he of Massacres of the Mountains, who makes quite a spirited defense of the fighting preacher and his one-hundred-day volunteers. Dunn calls Chivington “a colossal martyr to misrepresentation.” In his polemic Dunn points out, correctly enough, that there was a life-or-death struggle taking place on the western prairies in the early 1860s. The conflict was brutal; many immigrants did lose their lives.

It could hardly have been otherwise. The Indians were rapidly being squeezed out of the country that supported them—country they held dear. The tactical problem that the first Denver council tried to address, how to tell a peaceful Indian from a hostile Indian, was never solved. A fighter such as Roman Nose, a war Indian for sure, might nonetheless visit a peace Indian such as Black Kettle. Plains Indians moved around, visiting for a time with this band or that. The hostile and the peaceful were never to be easily separated out.

After the Fetterman Massacre in 1866, General Sherman made a blunt exterminationist remark. According to H. L. Mencken, it was Sherman, not General Philip Sheridan, who, when approached by an Indian beggar at a railroad depot with the claim that he was a good Indian, replied that the only good Indian he had ever seen was a dead Indian.

Sherman was not happy, two years later, at the end of what has been called Red Cloud’s War, when the government was forced into its only public retreat in the whole era of this conflict: it agreed to abandon three forts that had foolishly been thrown up along the Bozeman Trail. They had been supposed to protect miners and other travelers to Montana but happened to have been erected right in the heart of Sioux country. With what meager manpower the army had at the time they could not be defended.

The army had, for once, truly overreached—it had underestimated the power of the tribes. Custer was to make the same mistake at the Little Bighorn.

Once the forts were abandoned, the Indians burned them.

Part of J. P. Dunn’s admiration for Chivington stems from the fact that the fighting parson never gave ground. He never tried to shift the blame for Sand Creek to anyone else, or to pretend that he had intended to do anything other than what he did do: kill as many Indians as possible. Dunn’s argument is that at this stage of the fighting nothing but merciless cruelty would impress the Indians. He even argued that the mutilations had the same purpose: to convince the Indians that white men could deal in terror as effectively as they themselves could. He felt that the Indians did not respect gentle treatment, though he himself knew that they did respect fair treatment.

Dunn ends his defense with one of those purple perorations of which he was so fond:

Was it right for the English to shoot back the Sepoy ambassador from their cannon? Was it right for the North to refuse to exchange prisoners while our boys were dying in Libby and Andersonville? I do not undertake to answer these questions, but I do say that Sand Creek is far from being the “climax” of American outrages to the Indian, as it has been called. Lay not that unflattering unction on your souls, people of the East, while the names of Pequod and Conestoga Indians exist in your books; nor you of the Mississippi Valley while the blood of Logan’s family and the Moravian Indians of the Muskingum stain your records; nor you of the South, while a Cherokee or a Seminole remains to tell the wrongs of his fathers; nor yet you of the Pacific Slope while the murdered family of Spencer or the victims of Bloody Point and Nome Cult have a place in the memory of men—your ancestors and predecessors were guilty of worse things than the Sand Creek massacre.

That summary is hard to dispute. The burned-alive Pequots probably did have it worse. The reason Sand Creek gets highlighted is because some of those killed were prominent peace Indians. Black Kettle’s peaceful position had been well known for many years, but Chivington didn’t care. He attacked the largest encampment he could find—the more militant bands would not have been so easily found, and it’s doubtful that they could have been surprised. Black Kettle’s band was easy pickings precisely because they believed they were safe. To some extent Black Kettle compounded this lapse when he was attacked and killed on the Washita.

Arthur Penn’s rendering of Thomas Berger’s Little Big Man contains at least three massacres. The first might loosely represent Sand Creek, the second the Washita, and the third the Little Bighorn. If Americans—or even Westerners—remember anything about Sand Creek it is that Black Kettle was frantically waving his American flag as the troopers charged in. Some say his companion White Antelope was holding up a peace certificate when he was shot dead; it is more probable that he was merely making some gesture of surrender. From the point of view of poorly trained or wholly untrained cavalry, that there were a lot of peace Indians in this camp might not have been obvious. Most of the attackers were probably more frightened than enraged, though rage or at least adrenaline arrived quickly enough once the shooting started.

The mutilations the victors performed were horrible, though not nearly as encyclopedic as those the Sioux and Cheyenne managed to visit on Fetterman’s men two years later, in a battle that barely lasted half an hour. Here is what the troops found when they went out to bring in the bodies after the Fetterman wipeout: the words are those of Henry Carrington, at that time commander of Fort Phil Kearny, whose military career was destroyed by this disaster:

Eyes were torn out and laid on rocks; noses cut off; ears cut off; chins hewn off; teeth chopped out; joints of fingers; brains taken out and placed on rocks with other members of the body; entrails taken out and exposed; hands cut off; feet cut off; arms taken out of sockets; private parts cut off and independently placed on the person; eyes, ears, mouth, and arms penetrated with spearheads, sticks or arrows; ribs slashed to separation with knives; skulls severed in every form, from chin to crown; muscles in calves, thighs, stomach, breast, back, arms, and cheeks taken out. Punctures upon every sensitive part of the body, even the soles of the feet and the palms of the hand.

Considering the short duration of the Fetterman Massacre, as opposed to the nearly all-day struggle at Sand Creek, the Sioux and Cheyenne made Chivington’s men seem like amateurs of massacre, which indeed they were.

The same catalogue could be restated for the Little Bighorn, with the addition of decapitation and a few other refinements. Chivington’s hundred-day volunteers were for the most part Sunday soldiers, content with pouches made from scrotums and the like. When it came to making a meat shop they possessed only the crudest skills.

I am not sure that Sand Creek admits of any conclusions. Two peoples with widely differing cultures were rubbing against each other, constantly and insistently. The Indians were trying to defend their cherished way of life, the whites to make that way of life vanish so they could go on with their settling, farming, town-building, etc.

On a world scale countless massacres have been perpetrated over those and similar issues. Land is frequently a principal element in these disputes. Is it my land or your land, our land or their land? Time after time, in the Balkans, India, Pakistan, Kashmir, the Middle East, large parts of Africa, the same concerns develop. Peoples don’t seem to be good at sharing land, even when there’s a lot of it to share. Where land is in dispute massacres are just waiting to happen—it’s only a question of time, and usually not much time at that.