![]()

Harlem seemed a cultural enclave that had magically survived the psychic fetters of Puritanism. Negroes were that essential self one somehow lost on the way to civility, ghosts of one’s primal nature. . . . The creation of Harlem as a place of exotic culture was as much a service to white need as it was to black.

—Nathan Huggins, The Harlem Renaissance

![]()

What a crowd! All classes and colors met face to face, ultra aristocrats, Bourgeois, Communists, Park Avenuers galore, bookers, publishers, Broadway celebs, and Harlemites, giving each other the once over. The social revolution was on.

—Geraldyn Dismond, The Interstate Tattler

There were always two Harlems in the 1920s—the one that whites flocked to for pleasure and the one that (mostly) blacks lived and worked in. Guidebooks written for white readers presented Harlem as a “real kick,” “New York’s Playground,” a “place of exotic gaiety . . . the home-town of Jazz . . . a completely exotic world” where “Negroes . . . remind one of the great apes of Equatorial Africa.” Primitivists of many different stripes, from antiracists to racists and everything in between, held that white culture was dull, depleted, restricted, cold, without vibrancy or creativity, and that all the passion, purity, and pleasure it lacked was hidden away in black communities. That conviction was the foundation of what Langston Hughes called the “Negro vogue,” making Harlem, in James Weldon Johnson’s words, “the great Mecca for the sight-seer, the pleasure-seeker, the curious, the adventurous” and drawing whites to shows at interracial cabarets or to clubs that catered to their patronage. Gay and straight, male and female, white would-be revelers descended on Harlem from taxis and subway stations, in spring weather and in snowstorms, individually and by guided tour, in hopes of an evening’s dose of the life-giving force they believed in and that popular culture reinforced. Harlem, Variety promised, “surpasses Broadway. . . . From midnight until after dawn it is a seething cauldron of Nubian mirth and hilarity. . . . The dancing is plenty hot. . . . The [Negro] folks up there . . . live all for today and know no tomorrow. . . . Downtown Likes Harlem’s Joints.” One travel writer gushed, “Here is the Montmartre of Manhattan . . . a great place, a real place, an honest place, and a place that no visitor should even think of missing. But visit Harlem at night; it sleeps by day!”

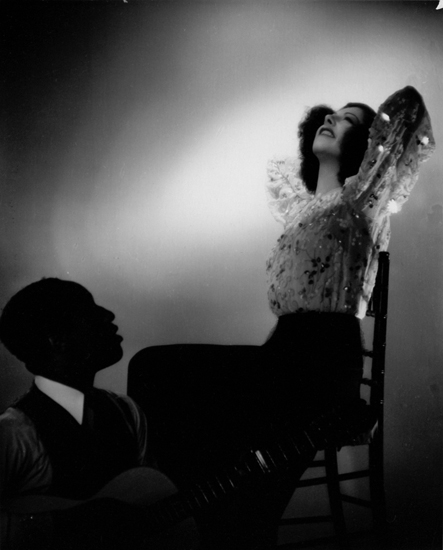

Libby Holman with jazz guitarist Gerald Cook.

Harlem did not, of course, sleep by day. White revelry was not its raison d’être. African Americans came to Harlem from all over the world, paying inflated rents and tolerating overcrowding, to experience a richly faceted black world. As Adam Clayton Powell, Sr., the pastor of the Abyssinian Baptist Church, put it, Harlem in the 1920s was “the symbol of liberty and the Promised Land to Negroes everywhere.” There were magazines, newspapers, and literary journals, and cultural institutions rich with community programs, such as the 135th Street Library (now called the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, after the collector Arthur A. Schomburg). There were patrons who wanted to support black artists. There were foundations such as the Guggenheim, Rosenwald, Garland, and Viking that were actively seeking African-American talent. The NAACP and the Urban League supported competitions, as did the Opportunity and Crisis awards, the Spingarn Medal, the Harmon Award, the Boni & Liveright award, and others. And there were literary salons and parties—writer Georgia Douglas Johnson’s, Walter White’s, the famous “Dark Tower” salon of hairdressing fortune heir A’Lelia Walker, and Carl Van Vechten and Fania Marinoff’s apartment—all providing space for black and white artists, intellectuals, musicians, and political leaders to mix and share ideas. It was a heady time, “a rare and intriguing moment,” in the words of Nathan Irvin Huggins, “when a people decide that they are the instruments of history-making and race-building.”

Harlem street scene.

If there was anyplace in the nation where race lines could be undone, that place seemed to be Harlem. Its interracial nightlife was legendary. Society columnists in the same papers that warned against race mixing thrilled to stories of Harlem’s “black-and-tan” parties and cabarets. Harlem was the country’s symbol of interracial relations, “a large scale laboratory experiment in the race problem,” as writer, NAACP leader, and professor James Weldon Johnson described it. The “Negro renaissance,” wrote Wallace Thurman, was a place “to do openly what they [whites] only dared to do clandestinely before.”

Goaded by that possibility, Langston Hughes wrote, “white people began to come to Harlem in droves.” They felt entitled to Harlem’s vaunted exotic sensuality and the escape it promised from urban capitalism’s alienation. As British heiress, activist, and Harlem aficionado Nancy Cunard put it, “It is the zest that the Negroes put in, and the enjoyment they get out of, things that causes . . . envy in the ofay [white person]. Notice how many of the whites are unreal in America; they are dim. But the Negro is very real; he is there. And the ofays know it. That’s why they come to Harlem.” White visitors flooded nightclubs and elbowed their way into literary events. “White America has for a long time been annexing and appropriating Negro territory, and is prone to think of every part of the domain it now controls as originally—and aboriginally—its own,” James Weldon Johnson commented. Those with money took up black writers and artists. Those with political aspirations threw themselves into Harlem politics. A visit to Harlem’s fabled cabarets was de rigueur for out-of-town tourists, who all wanted to go back home to Cincinnati, Seattle, or Dallas and shock their friends with stories of interracial drinking and dancing in New York’s celebrated black metropolis. The cabarets capitalized on white America’s desire for black exoticism, and they presented themselves, as Huggins puts it, as a “cheap trip . . . a taxi ride . . . thrill without danger.”

But there were upsides as well as downsides to being, as Langston Hughes put it, “in vogue”:

At almost every Harlem upper-crust dance or party, one would be introduced to various distinguished white celebrities there as guests. It was a period when almost any Harlem Negro of any social importance at all would be likely to say casually: “As I was remarking the other day to Heywood__,” meaning Heywood Broun. Or: “As I said to George__,” referring to George Gershwin. It was a period when local and visiting royalty were not at all uncommon in Harlem. And when the parties of A’Lelia Walker, the Negro heiress, were filled with guests whose names would turn any Nordic social climber green with envy. It was a period when Harold Jackman, a handsome young Harlem school teacher of modest means, calmly announced one day that he was sailing for the Riviera for a fortnight, to attend Princess Murat’s yachting party. It was a period when Charleston preachers opened up shouting churches as sideshows for white tourists. It was a period when at least one charming colored chorus girl, amber enough to pass for a Latin American, was living in a pent house, with all her bills paid by a gentleman whose name was banker’s magic on Wall Street. It was a period when every season there was at least one hit play on Broadway acted by a Negro cast. And when books by Negro authors were being published with much greater frequency and much more publicity than ever before or since in history. It was a period when white writers wrote about Negroes more successfully (commercially speaking) than Negroes did about themselves. It was the period (God help us!) when Ethel Barrymore appeared in blackface in Scarlet Sister Mary! [by white writer Julia Peterkin]. It was the period when the Negro was in vogue.

White women could get their names in the paper simply for showing up. Joan Crawford, Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney, Helena Rubenstein, Fannie Hurst, and Zelda Fitzgerald all found that useful. Torch singer Libby Holman made Connie’s Inn, the Clam House, and Small’s Paradise into second homes for herself and her bisexual posse of friends: Tallulah Bankhead, Jeanne Eagles, Beatrice Lillie, Louisa Jenney, and others, who liked to go to Harlem “dressed in identical men’s dark suits with bowler hats.” When Small’s Paradise moved, it advertised its new location in Variety by describing itself as a place where the (white) “high hats” who mingled with the (black) “native stepper[s]” came to dance.

There is an often-repeated apocryphal anecdote that recounts a black porter conversing with Mrs. Astor. “Good morning, Mrs. Astor,” the porter says, picking up her luggage. “Do we know one another, young man?” she asks, incredulously. “Why, ma’am,” he replies, “we met last week at Carl Van Vechten’s.” It didn’t matter that the story was not true. It nevertheless conveyed the idea that Harlem’s social world, to a degree unprecedented elsewhere in the nation, leveled social distinctions. No Harlem Renaissance novel, black or white, was complete without its requisite party or cabaret scene. Wallace Thurman’s Infants of the Spring vividly describes a rent party

crowded with people. Black people, white people, and all the in-between shades. . . . Everyone drinking gin or punch. . . . The ex-wife of a noted American playwright . . . confused middle-westerners, A’Lelia Bundles, Alain Locke . . . four Negro actors from a current Broadway dramatic hit . . . [a] stalwart singer of Negro spirituals . . . a bootblack with a perfect body, a . . . drunken English actor . . . a group of Negro school teachers . . . Harlem intellectuals . . . college boys, the lawyers, the dentists, the social service workers . . . [all] unable to recover from being so intimately surrounded by whites.

Real parties were even more extravagant. A’Lelia Walker Bundles, the daughter of Harlem’s first millionaire, hairdressing entrepreneur Madam C. J. Walker, was Harlem’s “great party giver,” and her elegant limestone town house at 108–110 West 136th Street was something to see. It had French doors, English tapestries, Louis XVI furniture, Persian rugs, a grand piano, and crystal chandeliers. “Negro poets and Negro number bankers mingled with downtown poets and seat-on-the-stock exchange racketeers. Countee Cullen would be there and Witter Bynner, Muriel Draper and Nora Holt, Andy Razaf and Taylor Gordon. And a good time was had by all. . . . Unless you went there early there was no possible way of getting in. Her parties were as crowded as the New York subway at the rush hour—entrance, lobby, steps, hallway, and apartment a milling crush of guests, with everybody seeming to enjoy the crowding.”

Harlem Renaissance physician and writer Rudolph Fisher captured the interracial excitement of these gatherings in his essay “The Caucasian Storms Harlem”:

It may be a season’s whim, then, this sudden, contagious interest in everything Negro. . . . But suppose it is a fad—to say that explains nothing. How came the fad? What occasions the focusing of attention on this particular thing. . . . Is this interest akin to that of the Virginians on the veranda of a plantation’s big-house—sitting genuinely spellbound as they hear the lugubrious strains floating up from the Negro quarters? Is it akin to that of the African explorer, Stanley, leaving a village far behind, but halting in spite of himself to catch the boom of its distant drum? Is it significant of basic human responses, the effect of which, once admitted, will extend far beyond cabarets? . . . Time was when white people went to Negro cabarets to see how Negroes acted; now Negroes go to these same cabarets to see how white people act.

All the sudden popularity could be offensive. The idea that blacks should provide a social safety valve for stifled white passions was especially insulting, as was the pressure to perform a version of blackness that satisfied whites’ expectations. “Ordinary Negroes,” Langston Hughes maintained, did not “like the growing influx of whites toward Harlem after sundown, flooding the little cabarets and bars where formerly only colored people laughed and sang, and where now the strangers were given the best ringside tables to sit and stare at the Negro customers—like amusing animals in a zoo.” One black newspaper called the influx of whites into Harlem “a most disgusting thing to see.” A 1926 article in the New York Age noted that “the majority of Harlem Negroes take exception to the emphasis laid upon the cabarets and night clubs as being representative of the real everyday life of that section. . . . All this has but little to do with the progress of the new Negro.” Wallace Thurman, usually known for irreverence, was uncharacteristically sober in objecting to the fact that “few white people ever see the whole of Harlem. . . . White people will assure you that they have seen and are authorities on Harlem and things Harlemese. When pressed for amplification they go into ecstasies over the husky-voiced blues singers, the dancing waiters, and Negro frequenters of cabarets who might well have stepped out of a caricature by Covarrubias.”

Others, however, while agreeing that the “vogue” was suspect and sure to be short-lived, advocated taking advantage of the sudden surge of interest as long as it lasted. Black novelist Nella Larsen urged her friends to “write some poetry, or something” quickly, before the fad ended. Zora Neale Hurston took white friends to hear jazz and see black church services. It never occurred to her to charge for doing this. Enterprising black tour guides, on the other hand, charged $5 a person for “slumming” parties of the Harlem cabarets. One “slumming hostess” mailed prospective white clients an invitation that read:

Here in the world’s greatest city it would both amuse and also interest you to see the real inside of the New Negro Race of Harlem. You have heard it discussed, but there are very few who really know. Because the new Negro will be looked upon as a novelty, I am in a position to carry you through Harlem as you would go slumming through Chinatown. My guides are honest and have been instructed to give the best of service, and I can give the best of references of being both capable and honest so as to give you a night or day of pleasure. Your season is not completed with thrills until you have visited Harlem through Miss _________________’s representatives.

Yet there were those who agreed with the black gossip columnist Geraldyn Dismond that the Harlem “vogue” represented an important cultural moment and was a form of “social revolution,” in spite of its limitations. For example, Chandler Owen, one of the editors and founders of the black radical journal The Messenger, believed that the racially integrated Harlem cabaret was “America’s most democratic institution . . . a little paradise within.” He argued that Harlem’s nightlife provided an education in interracial understanding unavailable elsewhere in the nation and was, hence, invaluable:

Here white and colored men and women still drank, ate, sang and danced together. Smiling faces, light hearts, undulating couples in poetry of motion conspired with syncopated music to convert the hell and death from without to a little paradise within. . . . These black and tan cabarets establish the desire of the races to mix and to mingle. They show that there is lurking ever a prurient longing for the prohibited association between the races which should be a matter of personal choice. . . . They prove that the white race is taking the initiative in seeking out the Negro; that in the social equality equation the Negro is the sought, rather than the seeking factor. . . . Fundamentally the cabaret is a place where people abandon their cant and hypocrisy just as they do in going on a hike, a picnic, or a hunting trip.

Harlem’s parties could be seen in a similar light. Carl Van Vechten and his wife, Fania Marinoff, threw spectacular parties in their apartment on West 55th Street (sometimes referred to as the “Midtown office of the N.A.A.C.P.”). According to Langston Hughes, they were parties “so Negro that they were reported as a matter of course in the colored society columns, just as though they occurred in Harlem.” Careers could be created from the networking opportunities such parties provided. Van Vechten’s daily notebooks detail that. Nella Larsen, who was trained as a nurse, married to a chemist, and working as a librarian—partly as an assistant to white librarian Ernestine Rose of the Harlem branch library—wanted to write her way into the “vogue” in 1927 but had no background as a writer. She wrote a short, intense novella about the myriad obstacles to a young black woman’s fulfillment. Without Harlem’s social whirl, it would have stalled.

Parties were her opportunity. On March 16, 1927, she went to a party at the Van Vechten–Marinoffs’ at which she mingled with Nickolas Muray, the era’s most important photographer; Louise Bryant, a New Woman activist and the wife of John Reed; Harlem celebrity James Weldon Johnson; William Rose Benét, the publisher of The Saturday Review of Literature; his wife, writer Elinor Wylie; and editor and publisher Blanche Knopf. Four nights later, she joined Van Vechten and Marinoff for another party, that time at the home of actress Rita Romilly, where she spent the evening with Harry Block, a senior editor at Knopf; T. R. Smith, the senior editor at Boni & Liveright (then the second most important publisher of black literature); and Blanche Knopf again. Nine days later, she joined some of the same group at a party that also included Zelda and F. Scott Fitzgerald, Walter White, Rebecca West, French writer Paul Morand, and others.

White editors such as Blanche Knopf were anxious for black manuscripts but also insecure about their ability to judge black literature. They leaned heavily on the advice of a few white advisers and favored black writers recommended by them, especially those they had come to know socially.

That month, Knopf accepted Larsen’s first novel, Quicksand. While it was being edited at Knopf, Larsen attended another party, on April 6, that included A’Lelia Walker; Paul Robeson; Walter White; Geraldyn Dismond; and the editor of the Chicago Defender, one of the most important black newspapers in the country. A few nights after that, she attended another small party with Van Vechten and Marinoff, Langston Hughes, and Dorothy Peterson, a poet and writer. Over the next few nights she attended parties given by Dorothy Peterson and by Eddie Wasserman, the heir to the Seligman banking fortune; these parties included such guests as Harlem Renaissance writer and gadfly Richard Bruce Nugent, poet Georgia Douglas Johnson, writer Alice Dunbar-Nelson, writer and editor Arna Bontemps, salonista and writer Muriel Draper, and, again, editor Blanche Knopf. In March 1928, Larsen won second place in the coveted Harmon Award for literature. In the fall of 1929, her second novel, Passing, was accepted by Knopf. She received a Guggenheim Fellowship. Passing was feted with a “tea” (cocktail party) at Blanche Knopf’s on the day of its publication, ensuring that it received widespread critical attention and good initial sales.

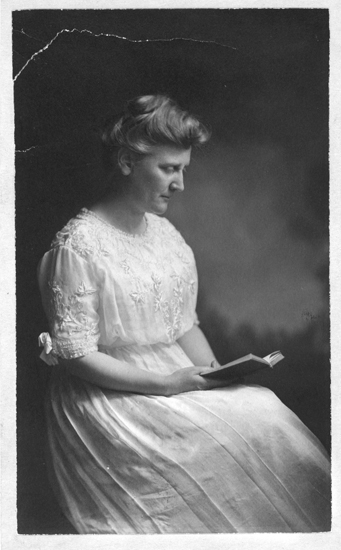

There were many forms of modern rebellion; Blanche Knopf in drag.

In spite of her extraordinary talent, without the social opportunities Van Vechten and Marinoff’s parties provided, such success might not have occurred. Those parties were Harlem’s Rotary Club or Chamber of Commerce. Once Larsen dropped out of that social world in the early 1930s, she never published again.

Most of the parties were hosted by women, principally the white women of Harlem. Indeed, Carl Van Vechten’s parties, as they are always known, were mostly the work of his wife, Fania Marinoff. She ordered the food, checked on invitations, and kept conversations from getting out of hand. Though often dismissed as inconsequential, hostessing was a way for white women to turn the roles available to them toward more professional goals. Dismissing these events as merely frivolous—in comparison with the serious work of culture building through journalism and organizing—has buried some of white women’s most earnest, if also sometimes awkward, attempts to take part in the “New Negro” movement. But given the world that Miss Anne entered and the unique place she occupied within it, sometimes awkward gestures were also deemed effective.

![]()

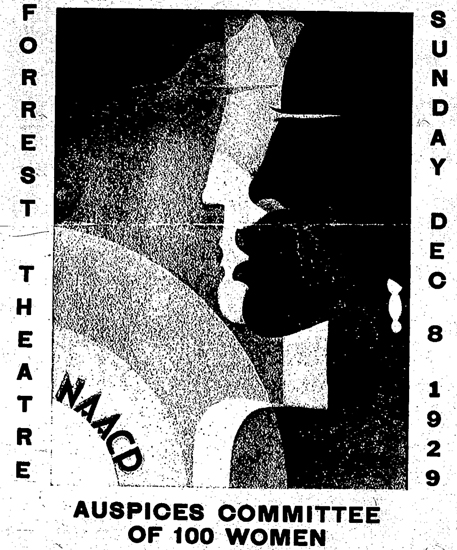

On December 8, 1929, black and white New York came together to raise money for the NAACP on the occasion of its twentieth anniversary. In spite of the stock market crash, the benefit, sponsored by the Women’s Auxiliary of the NAACP and produced by Walter White (in his new role as acting secretary) was completely sold out. White rented the four-year-old Forrest Theatre on West 49th Street (now known as the Eugene O’Neill Theatre) for the princely sum of $500 (just under $10,000 in today’s currency). The NAACP had already sponsored a midnight showing of the wildly successful all-black musical Shuffle Along, which White now intended to top with his own “extravaganza,” the “biggest benefit that Broadway has ever known,” he promised. He engaged more than two dozen of the most popular black and white performers of the day. Thanks to his aggressive lobbying, the lineup ranged from Duke Ellington with his Cotton Club Orchestra to blues singer Clara Smith to Jimmy Durante (already a jazz and vaudeville star). There were performers from the London production of Show Boat, the Jubilee Singers, and even a female impersonator. The entertainer White wanted most is unknown now, but she was one of the most sought-after performers of the 1920s, and White faced stiff competition to secure her for the benefit. She was a white actress and torch singer named Libby Holman. Holman performed in a wildly popular sultry blackface number called “Moanin’ Low” as a Harlem prostitute.

Hollywood head shot of Libby Holman.

Today it is hard to imagine blackface and the NAACP together. The “crippling” black image that blackface presented to whites—“childlike . . . comic . . . pathetic . . . foolish . . . vulgar . . . lazy . . . unrestrained . . . and insatiable”—reinforced “deep emotional needs” at the core of white racism. But blackface did not die with the Civil War or even with Reconstruction. Nor was it merely a southern form. Although black newspapers urged its demise, the form was still popular throughout the nation in the 1920s, “standard material for stage comedy.” The Harlem nightclubs that catered to whites regularly featured blackface comedians as well as mulatto chorines. The man or woman in blackface was a “surrogate” for the guilty pleasures of his white creators, licensing a range of behaviors that the “Protestant ethic” prohibited. Blackface could still be found from vaudeville stages to the Metropolitan Opera House, and it was performed for black audiences as well as white. There were renowned blackface performers of both races. In a nightclub description in James Weldon Johnson’s Autobiography of an Ex–Colored Man, black blackface minstrel performers, great black prizefighters, and Frederick Douglass are all accorded equal status as emblems of black achievement.

Libby Holman’s blackface “Moanin’ Low” had been the runaway hit of New York City’s 1929 season, and White had been especially determined to secure it for his benefit. “We would want by all means to have you sing ‘Moanin’ Low,’” he wrote to her.

New York’s literati turned out in force. Harlem novelist Nella Larsen rhapsodized about the “fantastic motley of ugliness and beauty” that made up the audience’s “moving mosaic” that night: “sooty black, shiny black, taupe, mahogany, bronze, copper, gold, orange, yellow, peach, ivory, white.” Carl Van Vechten, one of White’s advisers, was there with Fania Marinoff. Amy and Arthur Spingarn, benefactors and NAACP officials, had one of the six boxes available that night. So did Mary White Ovington, who was honored with a quarter-page photograph as the “mother” of the NAACP and whose family paid for a full-page ad for their department store. Alfred and Blanche Knopf also had a box, as did A’Lelia Walker. James Weldon Johnson and his wife, activist Grace Nail, attended. Artist Miguel Covarrubias, Harold Jackman, performer Taylor Gordon, and Geraldyn Dismond were all present. Most of the white women in this book were there. Nancy Cunard was in Europe in 1929, and Lillian Wood rarely left Tennessee. But Annie Nathan Meyer, Josephine Cogdell Schuyler, Charlotte Osgood Mason, and Fannie Hurst were all checked off, on internal NAACP memorandums, as responding favorably to requests to be patrons.

The show was a “huge success” financially and, in the eyes of the NAACP, an even bigger symbolic victory as a model of integration. Blacks and whites mingled freely throughout the $4 orchestra, $2 balcony, and $5 box seats of the Forrest Theatre. Such an intimate mingling, music historian Todd Decker has pointed out, was highly unusual in the still segregated 1920s. Even black celebrities such as Paul Robeson were “afraid to purchase orchestra seats for fear of insult” at most Broadway shows. The evening’s interracialism would have been “extremely difficult, if not impossible” outside the auspices of the NAACP.

Such a display was indeed cause for self-congratulation in the Jim Crow world of 1929. But it also entailed complications. Just a few months before the benefit, James Weldon Johnson had tagged those complications the special “dilemma” of the Negro artist. “The Aframerican,” he wrote,

faces a special problem which the plain American author knows nothing about—the problem of the double audience. It is more than a double audience; it is a divided audience, an audience made up of two elements with differing and often opposite and antagonistic points of view. . . . This division of audience takes the solid ground from under the feet of the Negro . . . and leaves him suspended.

Given the Forrest Theatre’s mixed audience, White’s choice to headline Holman’s “Moanin’ Low” seems peculiar indeed. Raw, undignified, and titillating, “Moanin’ Low” evoked an imaginary black “low life” steeped in sexuality, primitive emotions, and violence. Those were the very stereotypes the NAACP worked to contest as not “representative of the real everyday life” of blacks. Hence this performance of a mulatta prostitute begging her black pimp not to leave her—“My sweet man is gonna go / When he goes, Oh Lordee! / Gonna die / My sweet man should pass me by”—seemed destined to offend its black audience and pander to the worst misconceptions of its white one. Why, then, did Walter White pursue that particular piece so avidly? And why did black newspapers, usually quick to point out stereotypes, note only that the mixed audience had been “well pleased” by “Moanin’ Low”? Why was Holman not seen—as she surely would be seen today—as insulting her hosts and promoters—trespassing upon, rather than just impersonating, blackness?

Those who study whiteness would call such impersonation “onerous ownership,” the arrogant assumption of defining blackness. But not only were intellectuals such as White not offended; they welcomed an extraordinary range of responses to what Judith Butler calls “ready-mades,” or conventional ideas of identity. Many Harlemites felt that Nigger Heaven had focused too bright a light on Harlem’s cabarets and nightclubs and portrayed its citizens as possessing “a birthright that all civilized races were struggling to get back to . . . this love of drums, of exciting rhythms, this naïve delight in glowing colour . . . this warm, sexual emotion,” when they needed to be seen, by whites, as lawyers, doctors, professors, and politicians. Nevertheless, White’s souvenir brochure for the benefit included an essay by Van Vechten that encouraged blacks to “keep inchin’ along,” advice usually anathema to the militant spirit of the New Negro movement. It was not White’s only risky gambit that night.

The printed program, which sold for 50 cents as a souvenir brochure, with autographed copies auctioned off for much more, was designed especially for the evening by Harlem’s favorite artist, Aaron Douglas. Its cover image of a white man and a black woman, their facial silhouettes touching evocatively, bathed in the light of a radiating sun labeled “NAACP,” depicted one of the most taboo issues in race politics. Was White using his vaunted status as “voluntary Negro,” someone who had chosen the “struggle of the black people of the United States,” to make a point about interracial affiliation? If so, his program and his inclusion of Libby Holman both made space for Miss Anne in Harlem, suggesting that choosing—even impersonating—blackness over whiteness could be a meaningful act of solidarity. As someone who looked entirely white and who had to insist on his blackness daily, was Walter White suggesting that passing for black, performing as black, and identifying with blacks should be encouraged, not discouraged, throughout Harlem?

NAACP benefit program, close-up.

The space given to Holman by the NAACP would most likely have encouraged both Edna Margaret Johnson’s bid for acceptance and Nancy Cunard’s assumption, printed on the same page as Johnson’s “Prayer,” that she could speak as—and for—a black man bent on destroying racist “crackers.” With so much discussion in American culture of blacks crossing the “color line” and passing as white, it would have been inevitable that some white women—including Johnson and Cunard—would imagine a reverse crossing that passed from white to black.

![]()

I am possessed by a strange longing.

—James Weldon Johnson, The Autobiography of an Ex–Colored Man

Published anonymously in 1912 and reissued under his own name in 1927, James Weldon Johnson’s novel The Autobiography of an Ex–Colored Man was one of the most widely read books of the Harlem Renaissance. A novel of passing in the guise of a confession, this short work tells the story of an unnamed narrator who is pushed across the color line by the horrific sight of a lynching, described in gruesome detail. The narrator determines that he is “not going to be a Negro” henceforth and resolves to go to New York, where, because he looks white, it will not be “necessary for me to go about with a label of inferiority pasted across my forehead.” He goes to school, becomes a successful real estate developer, moves up in society, and finds that in almost all particulars, except the economic, the white and black worlds are nearly identical; it is class and culture, not race, that account for real differences between people. After some time in the white world he falls in love with a white woman, who agrees, after much torment, to marry him and keep his racial secret. They are a “supremely happy” couple. But she dies in childbirth with their second child. He continues to pass for his children’s sake: “there is nothing I would not suffer to keep the brand from being placed upon them.” At the end of the novel, the narrator ruminates on his life, remembering his mother (from whom he received his “coloured” blood). He wonders if he has been “a coward, a deserter” and if he has committed an unforgivable moral breach.

Before he can answer that question, however, he finds himself “possessed by a strange longing for my mother’s people.” His longing is strange because in learning that there is no real difference between the races, there should be nothing, in particular, for him to miss. His longing is also “strange” because the sudden desire to be among “his people” is so forceful, threatening to upend his carefully considered choices.

The power of this “strange” longing for blackness turns up everywhere in the black literature of the Harlem Renaissance. It is a disruptive force in both of Nella Larsen’s novels. Helga Crane, in Nella Larsen’s Quicksand, visits a “subterranean” Harlem cabaret, and finds it

gay, grotesque, and a little weird. . . . A blare of jazz split her ears. . . . They danced, ambling lazily to a crooning melody . . . or shaking themselves ecstatically to a thumping of unseen tomtoms. . . . She was drugged, lifted, sustained by the joyous, wild, murky orchestra. The essence of life seemed bodily motion. And when suddenly the music died, she dragged herself back to the present with a conscious effort; and a shameful certainty that not only had she been in the jungle, but that she had enjoyed it, began to taunt her.

She finds herself overcome, after this, with longing to be amid the “brown laughing” faces of “her” people and experience those “joyous,” essential feelings. She is “homesick . . . [for] her” people. And in Passing, Clare Kendry has crossed over into white society and finds that she cannot stay there because she too is overcome by her “longing” for blackness. That longing grows in her as a “wild desire . . . an ache a pain that never ceases.” Warned that this “wild desire” may destroy her marriage to a white man who does not know her secret, Clare responds, “You don’t know, you can’t realize how I want to see Negroes, to be with them again, to talk with them, to hear them laugh.”

This sudden longing is an important turning point in black authors’ novels of passing. Racial longing reinforces a racial ethic—the idea that “a refusal to pass is commendably courageous”—and vice versa. The longing to “come back” is an affirmation of race pride, a testament to the fact that there is nothing enviable in white culture. “A good many colored folks that try to be white find that it isn’t as pleasant as they imagined it would be,” Booker T. Washington is reported to have remarked. “White folks don’t really have a good time, from the Negro point of view. They lack the laughing, boisterous sociability which the Negro enjoys.” Turning one’s back on blackness is portrayed not only as betrayal but also as undesirable. This makes a coercive stricture into attractive preference. “Voluntary Negroes” are not only better people, in other words, but happier. What might otherwise have been a guilty pleasure, since an emotional preference for one race over another always smacks of essentialism, is reaffirmed as a proper ethical stance.

But a “strange longing” for blackness meant something quite different when expressed by white women. White women who believed in essential, or fixed and immutable, notions of racial identity often aligned themselves with primitivism’s conviction that blacks embodied a set of qualities and characteristics not found elsewhere. To them, attacks on biological difference seemed to fly in the face of their efforts to appreciate blackness as something very different from—and in some ways even better than—whiteness. Nor did they take to what was then a pragmatic position that eluded the question of what race was by insisting that whatever race was, it was an ethics, a mandate that blacks be loyal to their “own” people in the face of discrimination and oppression. White women animated by an erotics of race did not want to be loyal to “their” own race—that was the whole point. They wanted to qualify as “voluntary Negroes” instead (in spite of the fact the honorific was meant only for blacks who might have passed but chose not to). Simply put, some of the white women who were most taken with black Harlem also had a powerful personal—if unacknowledged—stake in some of the very ideas of racial difference that so vexed and frustrated the political/cultural movement. Their “strange longing,” as many would have called it, put pressure on the very thing most Harlemites wanted least to admit—that ideas of essential and immutable racial difference persisted, even among blacks and even though they were widely challenged.

Some of the most subtle literature of the Harlem Renaissance dramatizes this paradoxical persistence. For example, black novelist and Crisis literary editor Jessie Fauset, the stepdaughter of an early interracial marriage, demonstrates who can and cannot volunteer for blackness in her 1920 short story “The Sleeper Wakes.” Here, a blond, blue-eyed child named Amy is left with a middle-class black family when she is five years old, a family that is unable to tell her with certainty whether she is white or “colored.” Amy joins the white world but finds it sterile, cold, insolent, and acquisitive. “She wanted to be colored, she hoped she was colored.” Finally, she gives in to the “stifled hidden longing” for blackness. Because Amy might have black blood, might therefore be black, those longings are validated. Indeed, Amy’s longings are validations, in and of themselves, of black pride.

Miss Anne sometimes saw her exclusion from “voluntary blackness” as Harlem’s version of America’s “one-drop rule.” She protested against it by claiming also to have, as Charlotte Osgood Mason put it, the “creative impulse throbbing in the African race.” Seeing black poets proclaim “I am Africa,” she sometimes concluded, as Nancy Cunard did, that that she too could “speak as if I were a Negro myself.” On the one hand, Miss Anne had a point. What prevented such a claim, if not blood and biology? On the other hand, of course, such a claim was audacious, even outrageous. By suggesting that she could volunteer for blackness and that only an essential ideology could logically exclude her, Miss Anne managed at one and the same time to both validate black culture and challenge its racial edicts in almost equal measure. Hence, her mere presence seemed to undermine “rooted identity . . . that most precious commodity.”

Sexualizing Edna Margaret Johnson’s prayer for color made all the complexities of Miss Anne’s “strange longing” easier to dismiss. The white press, especially, went to extraordinary lengths to sexualize any longing white women expressed for blackness over whiteness. Civil rights activist and NAACP founder Mary White Ovington was a remarkable example of this phenomenon.

Like Nancy Cunard, Ovington was a socialist from a well-heeled family. And, like Cunard, she was a stubborn woman who strained her family’s tolerance as she doggedly transformed herself from dilettante to fighter. She rejected the mannered, 1880s Brooklyn Heights society in which she was raised: its balls, card games, fox hunts in the country, and long, chaperoned Sunday walks with suitors. Like Nancy Cunard, she resolved never to marry. “To live on in an eternal round of home duties without any outside fun or outside work even would just about kill me.” She moved from settlement work to NAACP leadership. Her parents were at a loss to understand her. “Do stand by me if you can,” she begged her increasingly distant mother.

Mary White Ovington.

Ovington was a very serious, even severe person. She was not at all a “New Woman,” demonstrating her feminism and independence through rebellious style. Born in 1865, she was in her late fifties during the Harlem Renaissance and the product of the very Victorian society that New Women like Cunard set out to affront. She disapproved strongly of their flamboyance and especially their provocative behavior with black men, which she felt drew the wrong kind of attention to integration. Hyperconscious of the “need for caution about appearances,” she saw “the nasty propaganda potential of any event with white women and black men.” Although Ovington used femininity to escape the constraints of womanhood that faced her, she did not believe in openly flouting sexual conventions. Adopting a personal style marked by decorous behavior and old-fashioned pastel suits helped her draw attention away from herself. She also deflected notice by working without a salary for forty years and being very careful about contradicting the NAACP’s black male leadership in public. So successful were her self-effacing strategies that to this day people are often unaware that she founded the organization.

Yet the press attacked this mild-mannered, middle-aged woman just as viciously as it attacked Cunard. Ovington was called a sexual hydra. She was accused of working for black rights only to insinuate herself sexually into the company of black men. Seizing on an interracial dinner she sponsored in 1908, long before such occasions were in “vogue,” front-page stories from The New York Times to the Chattanooga Times to the St. Louis Post-Dispatch exploded with “public disgust and indignation” over such a “disgraceful” social gathering. The press worked itself into a froth over the “forces of evil” represented by social interracialism and especially excoriated the “unbalanced” white women it insisted went to Peck’s Restaurant to seduce black men. Ovington was singled out for particularly ugly charges that she had ulterior motives for organizing the “Miscegenation Banquet,” as the press dubbed the dinner. If she wasn’t seeking black men for herself, then she was attempting to lure young white women into sex with black men, they insisted. “High priestess, Miss Ovington, whose father is rich and who affiliates five days in every week with Negro men and dines with them at her home in Brooklyn,” declared one southern newspaper, was determined to “take young white girls into that den.” A flood of threatening and “nauseatingly obscene” letters arrived at Ovington’s home, remarkably like the letters Cunard would receive nearly thirty years later during her own stay in Harlem. Ovington tried—as always—to put a brave face on things, declaring that “one is complimented to feel that one may have endangered one’s life for a cause.” But she was concerned enough to retreat to her sister’s home.

The papers did not always have to stretch to sexualize white women in Harlem. Certain white women, such as Cunard and Schuyler, were open about their sexual desire for black men. In those cases, the press had only to render such desire as monstrous, insane, unnatural, and unhealthy. Given the taxonomic fever of the twenties, that was not hard to do.

In the winter and spring of 1927, there was a string of mysterious and brutal attacks on Hollywood starlets. One of them occurred on April 12, 1927, when Helen Lee Worthing—a Ziegfeld Follies girl (named “one of the five most beautiful women in the world”) and screen star who had played opposite John Barrymore in Don Juan—was badly beaten by an intruder who broke her nose, knocked out a tooth, and left without attempting to take anything from her bungalow. Soon after her recovery, she vanished.

As it turned out, Worthing had eloped with her doctor, a black man, marrying in Mexico to evade California’s antimiscegenation laws. Fearing scandal in the press, she withdrew from her film and stage career after her marriage. “We didn’t intend for the story to get out,” her husband told reporters. The story did get out, however, and Worthing rushed to defend her love for the light-skinned black doctor. (Her defense was not the most thoughtful, conflating Negrophilia and Negrophobia: “We all have the blood of the chimpanzee in our veins,” she averred. “Why should I object to a taint race of dark blood in my husband?”) Worthing and Nelson challenged Hollywood to accept and defend them, making it known that if they could not win support from those in film, they’d go to Harlem “and accept all that her status as his wife implies.” Their gambit failed. Trying to win over her friends was a “losing game.” She encountered “no recognition or friendliness” when she appeared in her former social circles. “I might have been an utter stranger.” Other whites treated her as if she were “not quite human.”

Helen Lee Worthing with her husband, Dr. Nelson.

Worthing began to receive the same kinds of hate mail Ovington had received—an antagonism that may have been the cause of the attacks on her. Those “venomous, coarse, and vindictive notes” called Worthing “a disgrace to the white race,” a “sex-crazed degenerate,” and worse. “They were cruel, dirty, anonymous letters.” She felt afraid to go out. Her studio work dried up overnight, and “every one of my old friends had deserted me.” She “gradually withdrew from society,” isolating herself both from her Hollywood friends and from her husband’s friends in their black Los Angeles neighborhood and beginning to abuse drugs and alcohol. Two years into the marriage and desperately lonely, she collapsed. By November 1932, she was confined, against her will, in Los Angeles Hospital, pending a formal charge of insanity. A few years later she reappeared as a bathroom matron in a defense plant and then as a sewing machine operator in an apparel shop, working her way up from piecework to shop forewoman, still considered newsworthy by the tabloids. In 1948, she killed herself with an overdose of sleeping pills. “Worthing’s decline and her banishment from Hollywood served as a warning for many other stars who followed. Interracial relationships were clearly taboo.” A death like Worthing’s gratified those who thought “it was a sign of insanity to have a black lover and advertise the fact.” It proved that “white women who voluntarily married black men were . . . depraved, insane, or prostitutes” and sure to come to a bad end.

It is probably impossible, nearly a hundred years later, to recapture the social force of the term “Nigger lover.” The term was used to indict those who had transgressed whiteness in ways that now made them ineligible for it: whites who refused to discriminate, were intimate with blacks, or socialized with blacks. Women who were “Nigger lovers” were traitors to whiteness; they were guilty of acts of symbolic treason, and they forfeited whatever class privileges they had acquired. Having given up the only superiority available to them, they could be understood, in the terms of their day, only as self-hating.

Not everyone believed that interracial relations were doomed. Joel A. Rogers, for example, a friend of George Schuyler and the author, among other works, of This Mongrel World: A Study of Negro-Caucasian Mixing Throughout the Ages, and in All Countries (1927), argued that interracial sex had a “‘cosmic’ significance” and that white women who feared rape were expressing “an ungratified desire for intimacy with Negroes.” Schuyler applauded Rogers’s position and agreed with him, as did his white wife, Josephine. But they were in a distinct minority. Citing “incompatible personalities, irreconcilable ideals, and different grades of culture,” even Du Bois and the NAACP discouraged interracial marriage. According to Claude McKay, “the white wives of Harlem have had such a rough time from the Negro matrons that recently there was organized an association of White Wives of Negro Men to promote friendly social intercourse among themselves.”

Black activist and antilynching crusader Ida B. Wells called such women “white Delilahs” and resented having to defend them. But on balance, a woman such as Helen Lee Worthing may have been less troubling—at least she was predictable—than Edna Margaret Johnson with her “White Girl’s Prayer,” her “self-contempt,” and her glorification of all things black. When white women went to Harlem full of “strange longing” to escape from themselves into blackness, there was no telling what they might do.

Indeed, white women were often, for black communities, both unpredictable and dangerous. A second trial brackets the time period covered in this book, and it was every bit as influential in its day as the Rhinelander case was. It reinforced, for many, just how dangerous white women could be. And it reinforced, as well, how frightened white women might be of being perceived as choosing blacks over whites. The Scottsboro case began in the troubled Depression era, on March 25, 1931, when a fight erupted between black and white boys riding the rails in search of work in Alabama. Some of the white boys were thrown off the train and quickly ran to seek help from local farmers. In Paint Rock, Alabama, the train was stopped by a mob, which dragged the black boys off the train, along with two white women dressed in men’s overalls. The two women, Ruby Bates and Victoria Price, initially did not press charges or mention rape. But local officials quickly made it clear that “riding the rails, dressed in men’s overalls, consorting with rowdy white men, they could have been charged with vagrancy or worse.” Were they “nigger lovers”? the authorities demanded to know. Both women already had prostitution records. Neither had money or family to fall back on. “Bates and Price must have quickly recognized their stark choices. They could either go to jail or claim to be victims. They cried rape.”

No physical evidence supported the claim. At no time did either woman act as if she were recovering from a savage attack. No witness confirmed their stories. Yet in trial after trial, the Scottsboro Boys, as the defendants were called, were found guilty and sentenced to death. The case rose to prominence among progressives partly because such unfounded accusations had become so commonplace in the country. As Dan Carter, one of the historians of the case, puts it, Scottsboro “was a mirror which reflected the three hundred years of mistreatment they [blacks] had suffered at the hands of white America.”

“By the spring of 1932,” historian Glenda Gilmore wrote, “the Scottsboro case had traveled around the world and back again.” As whites began to grasp the workings of southern racism, the case created “tectonic shifts” in racial attitudes. Artists and writers came out strongly in defense of “the boys.” The case became a referendum on the nation’s racial future not only as a test of racism’s blind injustice but also as a referendum on political strategy, with militancy and caution at odds. Spearheaded in part by Mary White Ovington, the NAACP reluctantly took up the case. The Communist Party, in a campaign in which Nancy Cunard played an important role from Britain, did so as well, aiming to show up the NAACP as timid. Wrangling between the NAACP and the Communist Party continued for years. The case revealed to the nation what many in Harlem had long known: blacks were at risk of death at any time, for any infraction, real or imaginary. And white women played a very particular role in that threat; it was a role that was so deeply ingrained in history that saying no to their complicity in racist violence seemed nearly impossible. Some white women antilynching activists distanced themselves from the case when it became known that both Bates and Price had not only worked as prostitutes but also accepted black clients. “The women of the ASWPL [Association of Southern Women for the Prevention of Lynching, founded in 1930] were at a loss for how to address consensual interracial sex, something they had never considered possible before. . . . Consensual sex could not be officially imagined.” In this, as in myriad other ways, race and desire were conflated and collapsed.