![]()

Maybe I was African one time.

—Nancy Cunard

I longed for an American white friend with feelings such as mine—but alas, nary a one.

—Nancy Cunard

On a mild, cloudy Monday, May 2, 1932, Nancy Cunard returned to Harlem from a weekend in Boston, surprised to discover that William Randolph Hearst’s tabloid, the New York Daily Mirror, was stirring up a media frenzy with claims that “Steamship Heiress Nancy Cunard” and actor Paul Robeson were holed up at Harlem’s all-black Hotel Grampion. By dint of constant re-creation that few others would have dared, British Nancy Cunard had transformed herself from a “popular society girl” into an internationally known militant—simultaneously a modern icon of style and a model for rebels and radicals. Although only thirty-six years old, she had already endured (and sometimes enjoyed) nearly twenty years of minute tabloid attention from the British papers, which reported gleefully on all of her comings and goings as well as her hats, suits, jewelry, and makeup: “a mauve tulle scarf tied across her eyebrows, with floating ends, under a big gray felt hat, which looked, oh, so Spanish!” The Daily Mirror’s tale of an affair with the handsome, dynamic Robeson—himself an icon of Harlem’s “New Negro” masculinity—was just the sort of overagitated reporting Nancy loved to hate (and paste into her enormous black scrapbooks). Except for one thing. Almost every detail of the Daily Mirror’s story was wrong.

Nancy Cunard liked this photo of herself from the 1920s and kept it with her in her scrapbook.

Nancy Cunard was not new to Harlem. She was there for the second time and well on her way to becoming one of the most important and influential white women in Harlem—possibly the most influential. She was tired of being just a famous flapper. Now she was angling for acceptance by blacks. It was no time to have her political and aesthetic contributions trivialized or misreported.

Robeson’s white lover was not Nancy but another Englishwoman named Yolande Jackson. And Nancy’s black lover was not Robeson but the elusive black jazz musician Henry Crowder, who had accompanied her from Paris to Harlem the year before but this time had stayed behind. Robeson and Nancy hardly knew each other. And Nancy was in New York for business, not pleasure: fighting for the release of the nine black “Scottsboro Boys” and also collecting material for a comprehensive anthology of black life eventually published as Negro: An Anthology. She also had written an insider’s account of Harlem, which was about to be published; that made it all the more infuriating—and ironic—to be portrayed as one of the cabaret-hopping, naive white tourists whom her forthcoming article was preparing to blast.

One of the few things the newspaper story got right was the fact that Nancy and Robeson were staying at the same hotel, hardly surprising given that the Grampion was the only first-rate hotel in Harlem that admitted black guests. Nancy learned that Robeson was also at the Grampion by reading the Daily Mirror’s account. Had she known he was there, she would have sought him out and demanded to know why he was ignoring her repeated requests for a contribution to her anthology. She hated being ignored.

Nancy tolerated (relished, some said), a great deal of frivolous press attention. In spite of her painfully thin, boyish body and reputation for coldness—“one of those women who have the temperament of a man,” Aldous Huxley said—she delighted in becoming one of the most notorious sex symbols of the early twentieth century. She accepted “blather and ballyhoo” as part of the bargain of being the rebellious only daughter of eccentric Sir Bache Cunard and his wealthy American wife, Maud. But she was a stickler for accuracy. At pains to be taken seriously as a woman writer, she was especially hard on careless journalists. Just before midnight on May 1, she caught wind of the Mirror’s impending story and in her clipped, percussive style marched straight to a cable office, at 11:45 p.m. sending the editor, James Whittaker, a telegram that read, “Racket my dear Sir, pure racket, heiress and Robeson stuff. Immediately correct these. Call Monday one o’clock give you true statement. Nancy Cunard.” She now considered the matter closed. But Whittaker either did not receive Nancy’s telegram or—more likely—chose to ignore it. Nancy Cunard stories sold copies. The column ran in his morning edition.

Whittaker knew—as Nancy surely also did—that stories about single white women in Harlem would make good copy, especially in 1932, with the Depression deepening. However much other social taboos might be loosening, those against interracial sex remained entrenched. If a reporter could pair a “New Woman” with a “New Negro”—and Nancy and Robeson, respectively, exemplified those categories—so much the better. It was easy to play on the public’s conviction that Harlem was a haven of forbidden pleasures where wealthy white women appeared unaccompanied for one unspeakable reason. That sold papers. Newspapers from Haverhill, Massachusetts, to Duluth, Minnesota, carried Whittaker’s account under headlines such as “Lady Cunard’s Search for Color in New York’s Negro Quarter.” A hastily produced Movietone newsreel depicting “Lady Nancy Cunard” entering a “Harlem Negro hotel” also helped keep the tale alive. The British press eagerly picked up the story under such headlines as “Auntie Nancy’s Cabin Down Among the Black Gentlemen of Harlem.”

Nancy and Robeson both demanded retractions of what Nancy called the “outrageous lies, fantastic inventions and gross libels.” Robeson’s demand was printed; Nancy’s was not. Nancy wrote to Robeson that she knew “nothing at all of this amazing link up of yourself and myself in the press.” She lamented: “The sex motive is always used. . . . The Hearst publications invent black lovers for white women.” She called a press conference for noon at the Hotel Grampion and wrote up a statement to read to the dozens of reporters attending. “Press Gentlemen, how do you get this way?” it began. She spent the morning pacing, preparing, and strategizing, wondering why the papers could not be sane about race.

Nancy Cunard at her 1932 press conference with John Banting and Taylor Gordon.

At noon, dressed for her showdown, she strode into the hotel’s dining room, escorted by her friend the white English artist John Banting. She was a striking figure, “very slim with skin as white as bleached almonds, the bluest eyes one has ever seen and very fair hair,” and her unusual beauty combined “delicacy and steel,” as one of her admirers put it. Her “crystalline quality” made some people think she was “cold to the core.” But her problem was really the opposite: she cared too deeply about too many things, usually choosing things that others—other wealthy whites, at least—cared very little about. On that occasion, what she cared about was being misrepresented.

Like many highly sensitive people, Nancy liked to appear impervious. She had dressed with unusual care, adopting an understated version of the look that had become her signature. Her hair was wound under a multicolored crisscrossed turban, and she wore a tightly fitted red leather jacket; a dark, narrow, midlength skirt; colored hose; and black, pointed, high-heeled Mary Janes: militarism and girlishness combined. Usually she covered her arms from wrists to elbows in dozens of African ivory bangles. They were her trademark style—her “barbaric bracelets,” her friend the photographer Cecil Beaton called them. That day she sported just a bangle or two on each of her thin, white wrists, barely visible under her leather cuffs. The press had often noted her heavy hand with eyeliner. That day, she rimmed her eyes very lightly in kohl. She wore simple black earrings that hardly reached below her earlobes.

The lean and nervous Banting, wearing a light-colored three-piece suit, white tie, and two-tone shoes, escorted Nancy into the garishly decorated hotel dining room. He felt “half sick with horror” as they faced a roomful of reporters, notebooks at the ready. “I need not have been [afraid],” he soon realized, “for she stood up to the barrage smilingly in her bright armour of belief and her quick wit . . . expertly batting off the more stupid and destructive questions fired at her.” Fending off both honorifics and inquiries about Robeson—“it is NOT ‘the Hon[.] Nancy,’ it is Nancy Cunard”; “I met him once in Paris, in 1926,”—Nancy patiently explained that she’d been “disinherited” and that she had business in New York’s black neighborhood. She proudly told the reporters that her American ancestors had come out against slavery as early as 1680. Then she deftly steered the conference away from her private affairs and into the politics of race in America. She asked the assembled reporters to contribute to the Communist Party’s Scottsboro Defense Fund and demanded that they encourage their readers to weigh in on the question of why Americans are so “uneasy of the Negro Race.” The best answers would be reprinted in her upcoming Negro anthology, she promised.

Nancy was a single British woman trying to tell American newspapermen what to do. She did not get what she asked for. Rather than report that she was spearheading the British campaign to free the Scottsboro Boys or that her literary and political efforts had earned her many important friends in Harlem and the status of a Harlem insider, the newspapers continued their ridiculous Robeson story. It fitted perfectly with the “taxonomic fever” of the times: a cautionary tale for those who tried to step across race lines. Letters piled up at the Hotel Grampion’s reception desk. But they were almost all hate mail, of an unusually vicious sort.

As she later put it, “race-hysteria exploded.” By May 4, the beleaguered hotel staff found themselves with more than five hundred letters addressed to Nancy Cunard. These arrived from all across the nation: some typed, some handwritten, some scrawled with thick pencils, some merely unstamped envelopes weighted with slugs for which Nancy would have to pay postage. The letters insulted her, threatened her, and offered—in a variety of ways—to save her from herself. The letters called her “insane or downright degenerate,” “depraved miserable degenerated insane,” “a dirty low-down betraying piece of mucus,” and “a disgrace to the white race.” She was warned that she should “give up sleeping with a nigger” or be “burned alive to a stake. . . . Unless you leave America at once you will certainly be put on the spot and bump of[f] quick.” Most people would have destroyed these letters. Nancy saved them. She read them aloud to her friends. She published some of them in an essay entitled “The American Moron and the American of Sense—Letters on the Negro,” wanting others to see what she considered an “extraordinary” American display.

Such threats were not the worst of it. She kept but did not reprint even more violent and pornographic letters, unsettling testimony to her observation that “any interest manifested by a white person [in blacks] . . . is immediately transformed into a sex scandal.” “To stir up as much fury as possible against Negroes and their white friends,” she added, “the sex motive is always used.” Those “ornate and rococo outbursts . . . unsigned and threatening . . . sex-mad and scatological” combined violent homicidal fantasies with pornographic ones, fellatio and bestiality especially, making painfully clear the extent to which race-crossing was considered both unnatural and exciting. While calling her a “lousy hoor” with “insane uncontrollable passions” and a “nigger lover,” the letter writers begged for a meeting: “I am the one whit[e] man who would have my cock sucked by you, you dirty low down bum,” a typical one declared. Many proposed marriage: “I’m white, let me take you away and stop all these wagging tongues.”

Images of rebellious “New Women” saturated magazine and newspaper ads when a devil-may-care style was needed to sell perfume, clothing, upholstery, or exotic vacations. But the responses to Nancy Cunard’s presence in Harlem show that being a New Woman was not fancy-free. Those who crossed race lines, as she did, faced a violent, ugly backlash. Nancy Cunard was the sort of person who always went “too far,” carrying everything to extremes. That makes her racial experimentation, and responses to it, especially valuable to us now. She saved the “crazy letters, these frantic eructations,” because they demonstrated so vividly the combustible mix of hate, fear, desire, envy, disgust, and longing that powered racism then and still powers it today. They showed just what white women were up against if they forayed into Harlem. The letters demonstrated the way race and sex become linked, and they spotlighted how much she was braving. They raised a question that she never answered: what reward could possibly have been worth such a price?

![]()

She was of course a born fighter, and once again, a good hater.

—Charles Burkhart

In 1940, a Trinidadian poet named Alfred M. Cruickshank published a poem that asked why Nancy Cunard would forsake her privileges and status to throw in her lot with blacks. “What was it, Madam, made you to enlist / In our sad cause your all of heart and soul?” his poem “To Miss Nancy Cunard” asked. Nancy’s response, published a few months later, is telling. “My friend,” she wrote,

“Why love the slave,

The ‘noble savage’ in the

planter’s grave,

And us descendants in a

hostile clime?”

Cell of the conscious sphere,

I, nature and men,

Answer you: “Brother—

instinct, knowledge, and then,

Maybe I was an African one

time.”

That was Nancy’s central notion: that one could not only identify with others but also be—or become—them.

For most of our history, when identity has been central to political struggles, the demand has been to acknowledge others’ religious, ethnic, race, gender, sexual, or other identities and respect their intrinsic value. Rights claims have insisted on such recognition. Appeals to identification—to leaving behind “our own” identities to take on those of others—on the other hand, tend to inhabit the literary and artistic, rather than political, realms. The arts teach us to identify with others, to sympathize. For Nancy Cunard, identification was not just a means but a goal. Her notion was that identity itself, not just our regard for others’ identities, should be fundamentally reshaped and experienced as fluid, voluntary, open, alterable. That politics of identification was an idea born of privilege—the social mobility that comes with wealth—but what made Nancy Cunard so interesting was how heedless she was of leaving that privilege behind.

The idea of becoming others was nothing that anyone in her family would have propagated or even countenanced. Indeed, it was an idea that nothing in her background or her childhood could have foretold. But from a very early age, for no reason that she could explain, she was convinced that “maybe I was an African one time.” When she was six years old, she wrote, her thoughts first “began to be drawn towards . . . ‘the Dark Continent.’” She had “extraordinary dreams about black Africa,”

with Africans dancing and drumming around me, and I one of them, though still white, knowing mysteriously enough, how to dance in their own manner. Everything was full of movement in these dreams; it was that which enabled me to escape in the end, going further, even further! And all of it was a mixture of apprehension that sometimes turned into joy, and even rapture.

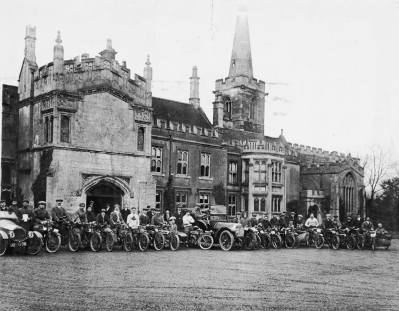

It is hard to imagine a more unlikely setting for these dreams than Nancy’s childhood home in Leicestershire, England: Nevill Holt. A photograph taken there in 1902 is shot across a wide expanse of gravel driveway to the estate’s massive gray stone entrance. A crenellated roof is visible over the doorway, as are small arched stained-glass windows and bell pulls used to summon the servants. The shadows are long, and the front door, two stories high, fades back into darkness. Standing in a small sunlit portion of the doorway is six-year-old Nancy, wearing black laced boots, a white skirt, a dark jacket, a white blouse, and a large white hat. The photo captures no one but her—no groundskeeper, governess, or housemaid. She gazes out from the doorway as if she were the only person in that colossal, shadowed world.

Nancy’s father, Bache Cunard, was a squarely built social conservative, a direct descendant of Benjamin Franklin and the grandson of the founder of the Cunard shipping line, a business in which he evinced no interest at all, preferring to live an English gentleman’s life of sports and hunting. It surprised nearly everyone when, at the mature age of forty-three, he suddenly married a wealthy twenty-three-year-old Californian named Maud Alice Burke, a lovely young woman who was passionate mostly about socializing and the arts. Maud’s family settled the marriage for a $2 million dowry (equivalent to roughly $83 million in today’s currency), a not uncommon arrangement during the “heyday of Anglo-American society marriage.”

The house to which Bache took Maud was “darkly paneled and full of armor, old swords, hunting prints and trophies and stuffed heads” and Maud hated it only slightly less than she hated the country life that it represented. The “incompatibility of the couple’s tastes and ways” became “local lore.” Maud considered motherhood “a low thing—the lowest.” But Nancy, their only child, was born, nonetheless, at Nevill Holt, on March 10, 1896, less than a year from the date of her parents’ marriage. It was an indifferent start.

There was nothing homey about Nevill Holt. Behind an iron gate and stone piers bearing a bull’s head and crown—the Nevill arms—the estate oversaw 13,000 acres of fields and rolling hills. It was a great mass of crenellated stone towers and battlements, occupying more square footage than the New York Public Library and without as much warmth. With roughly forty servants at work at any given time—gardeners, coachmen, grooms, maids, cooks, nurses, and governesses—it was more a small village than a family house, with grounds so vast that staff used bicycles to move about. The furnishings were museum-quality in every sense: “men in armour in the [Great] Hall . . . four types of tournament armour still in use in the reign of Henry VIII.” Nevill Holt’s stone and timbered interior was impossible to heat adequately, and even though Nancy’s bedroom was freezing cold, her “odious” governess, Miss Scarth, insisted that she take a cold bath daily, summer or winter. Nancy’s mother hosted frequent, extended house parties. During those, Nevill Holt was more like a very large resort hotel than anything else. Between parties, the enormous staff catered to the three Cunards so completely that they never had any great need of one another. Often they did not see each other for days. “It seems fantastic,” Nancy later wrote, “to think of the scale of our existence then, with its numerous servants, gardeners, horses, and motor cars.”

Nancy Cunard’s photograph of her childhood home, Nevill Holt. The estate was so vast that servants had to get around by bicycle. In spite of cutting all ties to her family, Nancy kept this photo of Nevill Holt with her until her death.

Nevill Holt was not only massive, cold, and dreary; it was also isolated. “Not allowed a step out of the grounds alone,” Nancy “had almost no contact with the land-people,” she complained. She “longed for friends of her own age.” Her parents were unusually ill suited to child rearing. Mostly, they ignored her. “Like most Edwardian society parents, Maud was content to leave her offspring in the care of nurses, tutors and governesses.” Nancy grew up “a strange, solitary child,” one friend remembers. “Somehow I felt—and was—entirely detached from both [parents]. She was, she wrote, a “sullen-hearted” child. Between her absent parents and her remote, isolated mansion, “my capacity for happiness was starved,” she concluded.

Nancy was trained in music, French, and literature and exposed to many of the successful writers of her day at her mother’s parties: “the nearest thing to a Salon that London has,” according to the British press. Maud (later known as Emerald) Cunard counted many brilliant, influential men among her friends and lovers, including George Moore, W. Somerset Maugham, W. B. Yeats, Ford Madox Ford, T. S. Eliot, Lenin, George Bernard Shaw, James Joyce, and Thomas Beecham. Her circle did also include some women—Violet Manners, the Duchess of Rutland; Pansy Cotton; Lady Randolph Churchill (the former Jennie Jerome); and later Wallis Simpson and Diana Mitford Mosley—but no one who could model for Nancy the kind of life she was seeking.

For years, however, that seemed not to matter. Nancy grew into one of the “fashionable beauties” of her time and seemed to accept that she would take her place in society. She happily teased the press, flirting with her growing image as a trendsetter. The papers predicted that she would stay “sweet, fresh, baby . . . dollish . . . and full of fun.” “Her hobby in life will probably be dogs,” one reported. Undergoing the traditional coming-out rituals of her class—“one ball succeeded another”—she performed ably as “[an] exquisite specimen of English girlhood.” She did a bit of private chafing, complaining that it was all “silly” men and “vapid conversation.” Nevertheless, in 1916 she made a traditional marriage to a socially suitable young man. Sydney Fairbairn was athletic, unliterary, good-looking, and pleasant. Twenty pounds heavier at her wedding than she would ever be again, Nancy presented herself as a “goldy bride” and a contented young woman.

It did not last. Fairbairn was every bit the mismatch for Nancy that her father had been for her mother. Nancy “went through with it all,” she later explained, as the only way “to get away” from “Her Ladyship,” as she always called her mother. But after twenty miserable months—which taught Nancy to give up ever trying to do what was expected of her—she determined to go her own way and to make, or find, a community that made more sense to her than the one she’d grown up in.

Her greatest asset was her extraordinary ability to empathize and identify with others. She often told a proud story about strolling in the Nevill Holt grounds with the writer George Moore, her mother’s lover and Nancy’s dear friend, and encountering a number of tramps: “generally dirty, slouchy men with stubbly chins and anger in their eyes.” She “wanted to run away and be a vagabond,” she told Moore. The story was a perfect combination of noble feelings and outrageous behavior. It was the sort of thing she would use to build her growing reputation. Her ability to feel and understand the pain of others helped her step into other worlds. Once she was there, her unusually high tolerance for discomfort—her own as well as that of others—kept her from becoming easily discouraged. She often failed to notice disapproval. That too, gave her a unique social footing, allowing her to take great risks but also setting her up for large failures. The question was what she would do with that combination of traits and proclivities.

A rail-thin, determined Nancy Cunard with her reflection.

Nancy had been writing poetry since her childhood, and her first published poem, “Soldiers Fallen in Battle,” set the stage for what would follow. Appearing in 1916, the year of her marriage, the poem asked who would speak for the voiceless:

These die obscure and leave no heritage

For them no lamps are lit, no prayers said,

And all men soon forget that they are dead,

And their dumb names unwrit on memory’s page.

The answer, for her, was clear. She would write their “dumb names” into public consciousness. Once she swerved from her class and its activities, the privileges and comforts she’d been born to quickly became intolerable. Gritting her teeth through every ball and dinner, she now felt keenly “the guilt of our immunity” from the sufferings of poverty and the war. How was it possible, she wrote in another early poem, “Remorse,” to have been so

wasteful, wanton, foolish, bold

. . . All through the hectic days and summer skies . . .

I sit ashamed and silent in this room.

She did not want to “live while others die for us.” Her world now became repellent to her, and she needed—desperately—to escape. “Were I not myself so irreducibly myself I should be very happy,” she told one friend. She now saw the struggles for freedom and “equality of races . . . of sexes . . . of classes” as “the three things that mattered” in the world. She needed to feel connected to them. “How hidden and remote one is from the obscure vortex of England’s revolutionary troubles, coal strikes, etc.,” she wrote in her diary. “So much newspaper talk does it seem to me, and yet—is it going to be always so?” Surely there was a way to live a more meaningful life?

Nancy moved to Paris in 1920, taking a small apartment on the corner of quai d’Orléans and rue Le Regrattier on the Île Saint-Louis, just down the street from her friend Iris Tree and around the corner from a small café frequented by expatriate Americans. There were a number of salons on the tiny island, as well as Three Mountain Press, from which she would later buy her gigantic Belgian Mathieu printing press. In Paris, she quickly became central to a growing circle of modernists and surrealists. She “knew everybody, was known by everybody,” Janet Flanner remembered. The British writer Harold Acton claimed that she had inspired and probably slept with “half the poets and novelists of the twenties.” Among her many lovers were the artists and writers Ezra Pound, T. S. Eliot, Michael Arlen, Robert McAlmon, Louis Aragon, Richard Aldington, Tristan Tzara, Wyndham Lewis, and Aldous Huxley, all key modernists. The intellectual circle she assembled was a who’s who of the avant-garde, including the writers Bryher (Annie Winifred Ellerman), Sybille Bedford, Ernest Hemingway, Janet Flanner, Solita Solano, Havelock Ellis, Djuna Barnes, and John Dos Passos; the artists Man Ray and his model Kiki de Montparnasse, Marcel Duchamp, Constantin Brancusi, Cecil Beaton, the surrealist André Breton, the photographer Berenice Abbott, and George Antheil; writer-activists such as Kay Boyle; and powerful collectors and tastemakers such as Peggy Guggenheim. Nancy’s poetry was published by Leonard and Virginia Woolf. Her slick-haired, cigarette-smoking, dark-eyed image began to appear everywhere, and her lean, elegant, and carefully exotic look—embodying the decade’s new freedoms—became synonymous with rebellious style. Before she knew it, Nancy Cunard had become “legendary”:

She was photographed, armored from wrist to shoulder in her African bracelets, by Cecil Beaton and Man Ray; and her sapphire-blue eyes, darkly rimmed with kohl, were often to be seen gazing mesmerically from the pages of glossy magazines. Inevitably, but hardly ever successfully, she was imitated, so that scores of lesser leopards slank along the corridors of expensive hotels, helmeted in cloche hats or turbans, their hair cut short, dyed gold, and arranged in two strands (which Nancy herself called “beavers”) curving over the cheekbones like twin scimitars.

A “toast of the twenties,” the papers called her.

If becoming a “toast” and a “legend” had been her goal, Nancy could have celebrated. Instead she found herself increasingly dissatisfied. The modernists she’d so admired now struck her as mock rebels, claiming to eschew conventionality while clinging to comfort and tradition. “Their manners, exalting high-mindedness and ostensibly rebelling against class, were hypocritical. They continued to enjoy the world of high society and the things it could afford.”

Losing faith in the modernists soured Nancy on the twenties altogether. “Why the smarming over ‘The Twenties,’” she would later sneer. “To hell with those days! They weren’t so super-magnificent . . . [not] in the least amazing.”

As she had done in her childhood, she once again turned her gaze toward Africa. Like Charlotte Mason, she had already accumulated a remarkable collection of African art: sculptures, shields, beading, masks, bottles, paintings, carved horns and tusks, music boxes, rugs, and, most famously, ivory bracelets in all shapes and sizes, which she wore “elbow deep.” She tallied the bracelet collection alone at 486 pieces, probably the largest such collection in the world. The objects helped keep alive the connection she had felt to Africa going back to her childhood dreams of “the sand, the dunes, the huge spaces, mirages, heat and parchedness.” But she did not want to just love, collect, and appreciate things; she wanted the “vital life-theme” of human “contact.” That meant knowing blacks, being accepted by them, becoming a part of their world. She did not want to flounce in and out, merely skimming the surface as a cultural tourist, though primitivism had made such tourism fashionable. In 1915, she glimpsed what “contact” might look like when her modern friends introduced her to jazz. They heard “tom-toms beating in the equatorial night” when they went to see the bands. But Nancy heard something else. And she saw the possibility of being “one of them, though still white.”

![]()

Nancy had a very advanced formulation of equity, ethics, and morals. It was as exceptional as it was different.

—Hilaire Hiler

If it is not easy to document what Nancy Cunard was seeking, it is easier, since she was very vocal on this score, to document just what she wanted to avoid and subvert. Chiefly, she hated any and all cultural scripts. She detested traditions. Believing that “common sense” was “NON-SENSE (in the true meaning of this word: a thing without reason, of no sense),” she tended to feel that she was on the right track when the majority found her incomprehensible.

Loneliness can challenge rebels, lure them back into the fold. Nancy Cunard had the advantage there. Aristocratic isolation had already inured her to loneliness. Her high tolerance for isolation made her unusually brave. She could use it to dispense with all but the most stalwart companions. That let her venture farther out on limbs than most people would have found comfortable. Isolation may have been a source of unhappiness for her, but it was also a kind of ballast. “One should learn how to live entirely alone from childhood,” she once wrote to a friend.

Nancy felt strong inducements to broadcast her interest in blackness, her “blacklove” as some would have called it. Broadcasting her views was not only Nancy’s way but also part of her conviction that she could turn publicity—good or bad—to her own purposes. Public pronouncements enabled a final break from the society of her parents. That demonstrated her fitness for entering black society. As far as she was concerned, since identity was declarative and associative, having little—if anything—to do with birth or family, announcing her affiliation with blacks and declaring herself to be “one of them, though still white” made it so. To her, it made perfect sense that in spite of every imaginable difference in cultural and national background, she could “speak as if I were a Negro myself.”

Harlemites did not necessarily see things that way. Few ideas are as riven by contradiction and confusion as American ideas of race. Nancy’s conviction that whites could, and should, volunteer for blackness underscored many of those contradictions. It highlighted the tension within Harlem, between seeing race as a social construction to be debunked and treasuring it as a deep essence. Nancy’s idea of volunteering for blackness was mixed with her own agendas, both flattering and offensive, appealing and alarming.

Race-crossing did not work the same way for white men and white women. White men were encouraged to cross races to offset the supposedly soul-crushing effects of industrialized economic modernity. For them, the spiritual power of primitive blackness was thought to be restorative, a force that could regenerate their souls, restore their creativity, and charge their sexuality. Taken in small doses, blackness would strengthen, not threaten, their essential identity as white men. Not so for white women. In 1926, the French art dealer Paul Guillaume proclaimed that “the spirit of modern man—or of modern woman—needs to be nourished by the civilization of the Negro.” But Guillaume, one of primitivism’s most influential proponents, was decidedly in the minority in his inclusion of women. White women’s sexuality was not widely seen as needing a powerful charge. And women’s souls were seen not only as undamaged by industrial and economic modernity but as impervious to its negative effects, insulated and protected by the home and domestic sphere over which they were expected to preside. Unlike white men, who were urged to take medicinal doses of black culture, white women were cautioned that overexposure to blackness would ineluctably alter their nature. A white woman who overexposed herself to blackness, by duration or degree of intimacy, risked becoming black by association, developing “Black skin” and forfeiting white status: “darkening your complexion,” as one angry letter writer put it to Nancy Cunard.

Nancy with a mask from Sierra Leone.

A white woman who had “gone Negro” (as the U.S. State Department described Nancy) not only became less white but also became less female, untethered from both racial and gender norms and adrift without a social category at just the moment when identity categories reached the apex of their cultural importance. An infusion that was promoted as curative for white men was prohibited as a pollutant for white women. Hence, opting into Harlem was, for white women, a far more consequential decision than it could have been for any of their white male counterparts or peers. It was, as one black French friend of Nancy’s wrote her, a bold move: “White men have contributed their support, which is all well and good, but when a white woman, or Lady, I should say, of your caliber condescends to engage in the bitter, exhaustive and ostensibly impossible struggle, than that’s a phenomenon. . . . I think you are the most marvelous woman in the world.” It was, as Nancy’s first biographer put it, “a sign of insanity to have a black lover and advertise the fact.”

Race-crossing was especially a minefield for Nancy Cunard. Described by one of her friends as “incapable of restraint or discretion,” she had an almost preternatural energy. If she had been a car, she would have had one speed: ninety miles per hour. “I find life quite impossible,” she once declared, “as I cannot enjoy a thing without carrying it to all extremes.” Whatever she pursued, she chased with her whole being, unable to stop in midstream, reassess, pull back, change course, or even note the passing landscape. She had neither interest in nor skill at the arts of compromise. Her attempts to opt into blackness helped advance the racial politics of the Harlem Renaissance because she seemed to put into practice what many were then theorizing about the mutability, flexibility, or “free play,” as we say now, of identity. But at the same time, her celebrity, and her stubbornness, threatened to topple some of those very advances and goals.

Many white women in Harlem went to great lengths to avoid exactly the sort of press attention that Nancy Cunard encouraged. Josephine Cogdell Schuyler, for example, claimed to be “colored” on her marriage certificate and did much of her best writing under various pen names. Mary White Ovington and Annie Nathan Meyer honed carefully crafted matronly roles to keep the scandal-mongering press at bay. Lillian Wood never bothered to correct the misimpression that she was black. Charlotte Osgood Mason was fanatical about not being mentioned in public. But Nancy Cunard wanted nothing of evasions or caution. A determined New Woman, she crafted a persona in which her posture of brave border crossing and “extreme” sensuality (in reality, she was reputed to experience little pleasure in sex) were crucial components, and no amount of political pressure could induce her to tamp those down.

Privacy never mattered to her. Harlemites, however, placed a high value on discretion. Nancy Cunard failed to grasp, and therefore to respect, that value. Nor did she ever accept the idea that one should tread carefully so as to protect the larger community and its goals. She had, as one black friend remembered, “an unfortunate faculty for producing reams of scandalous publicity.” Nancy “liked to shock.” She seemed, moreover, unaware that shock was a weapon more easily wielded by the privileged than the powerless. To some, she seemed to have more to gain from Harlem than she could offer it. The black journalist Henry Lee Moon put his skepticism this way, wondering if she was

just another white woman sated with the decadence of Anglo-Saxon society, rebelling against its restrictive code, seeking new fields to explore, searching for color, she was not to be taken seriously. I must confess that I shared with Harlem the quite general impression most effectively expressed by a slight upward twist of the lip and a vague shrug of the shoulder.

Certainly her idea that identity was desire and that you could choose new identities and adopt those of others was something that would not necessarily appeal to those she was trying hardest to court: Harlem’s blacks could ill afford any appearance that they wanted to be white. All that made Nancy Cunard a difficult ally for those with whom she most wanted to align herself. She made her friends in Harlem uncomfortable. “Nancy’s back, we’re in trouble,” they would say. “Hold onto your hats, kids, Nancy’s back!”

Fortunately, Nancy also had an extraordinary work ethic. And if there was one thing that many Harlem intellectuals understood and valued, it was hard work. None of them, including the privileged and patrician Du Bois, had been handed or inherited success. Zora Neale Hurston had launched herself up from rural Florida, without clothes or cash, arriving in Harlem with little but faith in her own talent and a willingness to work; her jobs included being a secretary and selling fried chicken. Langston Hughes had worked as a busboy, an assistant cook, a launderer, and a seaman. Countée Cullen, considered by many to be the finest poet of the Harlem Renaissance, had been abandoned by his mother, taken in by relatives, and forced to make his own way. To them and others, Nancy’s willingness to roll up her sleeves and escape her own advantages was endearing. Her delight in discomforting other whites afforded a guilty pleasure that Harlemites could watch with glee. Langston Hughes, who had a keen sense of the joys of discomforting others, adored Nancy Cunard and remembered her as “one of my favorite folks in the world!” One of Nancy’s “coloured friends in Harlem” remembered that “all of them loved Nancy and all deplored her.”

Between her intransigent personality and her complex ideas of identity, Nancy Cunard—by accident or design—became a kind of cultural litmus test for how far the racial politics of the 1920s and 1930s could be pushed. No other white woman in Harlem had the potential to contribute as much to Harlem’s racial experiments. On the other hand, no other white woman had the potential to do as much harm.

![]()

Among all of us in the avant-garde in Paris, Nancy was by far the most advanced. She was doing something about the central issue of our time, the Negro people.

—Walter Lowenfels

Dorothy Peterson once asked [Salvador] Dali if he knew anything about Negroes. “Everything!” Dali answered. “I’ve met Nancy Cunard.”

—Langston Hughes

By the mid-1920s, Paris and Harlem presented the greatest possibilities of interracial “contact.” Paris was so much in thrall to its own “black craze,” fueled in part by the arrival of international superstar Josephine Baker, that some were calling it the “European version of the Harlem Renaissance.”

Black was the color of designer high fashion for women: black stockings, black dresses, black hats, black blouses. Consistent with the latest mode, women’s hair was dyed black, bobbed, and carefully kinked. Dark-skinned men became even more popular as companions, as French women asserted that “dark-complexioned men understand women so much better.”

One French Vanity Fair reporter wrote that he could not take his eyes off the “tom-toms” in Montmartre’s jazz and the white ladies “swaying luxuriously in the long arms of dark cowboys.” In 1925, Nancy went to one of Josephine Baker’s first French performances and wrote a glowing review in the French Vogue, praising Baker’s “astounding . . . wild-fire syncopation.”

But admiring black performers and frequenting their clubs went only so far. Nancy was learning that nightclub “encounters between black and white women did not lead to enduring friendships.” As enticing as interracial contact now looked, it was not as easy to achieve as someone so accustomed to getting her way might have imagined.

Her interracial breakthrough occurred, ironically enough, only when she traveled out of France to Italy in the late summer of 1928. With her lover Louis Aragon, her friends Janet Flanner and Solita Solano, and her cousins Edward and Victor Cunard, she traveled to Venice, as she had been doing for many summers. They went to balls, barge parties, and carnivals; dressed in “glittering” costumes; danced until dawn at some of the “sinister new night-bars.” It was, she later said, a “hell of a time . . . gay and mad, fantastic and ominous . . . spectacular.” She almost forgot that she was discontented. One rainy night, she and Edward took a gondola to the oldest hotel in Venice, the Hotel Luna, to eat dinner and dance. The Luna was featuring an American jazz band, Eddie South’s Alabamians: “coloured musicians . . . so different to all I had ever known that they seemed as strange to me as beings from another planet . . . the charm, beauty and elegance of these people . . . their art, their manners, the way they talked. . . . Enchanting people.” “A new element had come into my life, suddenly,” she later said. She immediately took to Henry Crowder, a piano player with “great good looks . . . partly Red Indian,” who was older than Nancy and whom she found “thoughtful” and “serious-minded.”

Henry Crowder’s background could not have been more different from Nancy’s. The child of Georgia Baptists, Crowder came from a large family (twelve children) in which both parents worked: his father as a factory worker and carpenter and as a church deacon, his mother as a cleaning woman. Before becoming a professional musician, Crowder had been a postal worker, a dishwasher, a handyman, a chauffeur, and a tailor. When Nancy met Henry, he was married and had a young son. Henry had been trained all his life “to hate white people,” and the last thing he needed was a white woman. Nancy had the opposite response. She felt that she’d been looking for Henry all her life. “My feeling for things African had begun years ago with sculpture, and something of these anonymous old statues had now, it seemed, materialized in the personality of a man partly of that race,” she wrote.

A romance developed almost overnight, and its intensity surprised them both. Nancy had a reputation for being difficult and mercurial with her lovers. But with Henry she was “the sweetest woman I have ever known,” he said.

He followed her back to Paris and from there to her country house in Réanville, where he composed music and helped her launch her small press, The Hours. Henry, Nancy wrote, did “billing and circulars and parcels . . . and he drove the car too; he was indispensable.” The Hours was one of the most successful small presses, in large part because Nancy and Henry worked so hard—as many as eighteen hours a day, hunched over a massive two-hundred-year-old Belgian machine in semidarkness, setting type by hand, their fingers coated in printer’s ink, their shoulders, neck, back, and knees aching.

Many of Nancy’s friends were supportive of her affair with Henry, if a bit baffled, but some took it for granted that he was a “caprice” or “sexual drug.” “He has,” Richard Aldington said, “the poise, the sense of life of the blacks, which we whites are losing.”

Nancy’s account of “the first Negro I had ever known,” on the other hand, describes finding a “born teacher” in Henry, who

introduced me to the astonishing complexities and agonies of the Negroes in the United States. He became my teacher in all the many questions of color that exist in America and was the primary cause of the compilation, later, of my large Negro Anthology. But at this time I merely listened with growing indignation to what he had to tell: of the race riots and lynchings, the segregation in colleges and public places, the discrimination that was customary in all aspects of life.

Nancy’s friends were “astounded and revolted” by what they learned, through Henry, about American racism. “They had not realised its existence,” Nancy wrote. She refused to be revolted. She felt that she must do something about what she had learned. She could not sit in a dining room, tsk-tsking about the world, while others paid for her advantages.

Sometimes the least sentimental people seem to respond most powerfully to the suffering of others. Nancy was often described as calculating, and many of her lovers complained about her lack of proper feminine feeling. But when it came to her embrace of blackness, her emotions were on the surface. “Her vast anger at [racial] injustice embraced the universe,” Solita Solano remembered. “There was no place left in her for the working of any other emotional pattern. . . . It was her mania, her madness.”

Their life in Nancy’s Normandy farmhouse, sixty miles from Paris, was productive. They ran their press out of an unheated stable without having to bother with the “conventions and long-established rules” that governed other printers. They were relieved to be away from the troubles of Nancy’s Paris friends, who were drinking and using drugs to excess and sometimes suicidal. The Hours produced beautiful small books and, because it had almost no overhead, could give its authors—George Moore, Laura Riding, Robert Graves, Samuel Beckett, and Ezra Pound, among others—more than three times the usual royalties. But life in Réanville was almost as isolated as life at Nevill Holt had been. Henry was folding neatly into Nancy’s world, but aside from a brief friendship with the wife of one of Henry Crowder’s former bandmates, she was not folding into his. And if they were pleasantly protected, they were also cut off. Nancy, Henry remarked, was “at a loose end.”

Other troubles presented themselves, and in the seclusion of Réanville the contrast between Nancy’s and Henry’s personalities became glaring. Nancy was bossy, impulsive, and filled with energy. She was also physically ill, and she exacerbated her illness by not eating. “A snack now and then, but seldom a regular meal; she looked famished and quenched her hunger with harsh white wine and gusty talk.” Henry was cautious, deliberative, diffident, inexpressive, and prone to crabbiness. He resented what he believed to be Nancy’s wealth, complaining bitterly about being dependent on her while also expecting her to support him. He felt entitled to more than his weekly salary and could not believe that Nancy was as cash-strapped as she claimed. He became reckless: smashed the car, embroiled them both in a difficult legal settlement, demanded that Nancy buy him another car, then groused about having to share it with her. As the world moved toward an economic depression and what profits The Hours earned had to be poured back into the press, their situation worsened. The work of running the press became ever less romantic as “the back-breaking as well as wrist-breaking” tasks wore on. Nancy loved printing—“everything about the craft seemed to me most interesting”—but neither she nor Henry had a head for business. Both of them tired of distribution, correspondence, and bookkeeping, which all “greatly added to the work of the ‘firm.’” Nancy’s bed was “always littered with papers . . . correspondence, proof-reading and accounts. . . . Work never seemed to stop.”

In 1930, The Hours moved to Paris, where Nancy took a long lease on a shop on rue Guénégaud, a steep side street around the corner from the surrealists’ main gallery on the Left Bank, and she and Henry took rooms at separate, but nearby, hotels. Back in the city, Nancy increased her pace to a fever pitch. “The shop,” a friend remembered, “had an hysterical atmosphere. Nancy could never rest. . . . The clock did not exist for her; in town she dashed in and out of taxis clutching an attaché case crammed with letters, manifestoes, estimates, circulars and her latest African bangle, and she was always several hours late for any appointment.” Unsure of her next move, she became reckless as well. According to a later account by Henry Crowder, she initiated affairs with two other black men, one white woman, and a young white man roughly half her age named Raymond Michelet. “It was an absurd life,” Michelet recalled. “She lunched with one, passed the afternoon with the other, dined with the first, and spent the night with the second. In each, she went to the limit.”

Nancy and Henry stayed together on and off until 1935, in spite of all their troubles. Her attitude toward monogamy humiliated him and left him bitter, although he had been married when they met and remained married throughout their affair. In later years he would claim that Nancy had taken advantage of her race and class privileges first to seduce him and subsequently to bully him into accepting their “peculiar association.” For her part, Nancy never had an unkind word to say about Crowder and always credited him with opening blackness for her. “Henry made me,” she said.

The more demanding and difficult Henry became, the more Nancy tried to honor and placate him. She now embarked on an ambitious project designed to highlight what she insisted were his latent skills as a natural composer. She arranged for him to set poems by some of her most successful and prominent friends—Richard Aldington, Walter Lowenfels, Harold Acton, and Samuel Beckett—to music. She would contribute a poem as well, she promised. To devote more time to the project, she turned the press over to an associate, Wyn Henderson, and she and Henry drove off—“very fast”—to southern France in Henry’s blue sports car, “The Bullet,” renting a tiny cottage and a small upright piano that had to be brought in with an oxcart. There they completed the volume, Henry Music, in one intense month of nonstop work, and Nancy arranged for Man Ray to do the cover: a photomontage of her African art collection and a photo of Henry, with Nancy’s bangle-draped arms covering his shoulders like exaggerated epaulets. Man Ray’s cover opened out to reveal an array of African art and instruments, above which floated Henry’s face. The message that Nancy intended was clear: Henry was the modern embodiment of all that was best in the African legacy, all that Nancy loved most. The book was printed in a small, elegant edition of 150 copies. On Nancy’s copy Henry inscribed “To describe requires one with more linguistic capabilities than I possess. She is the one rare exquisite person existent. I love her I adore her. She is everything to me. I wish her happiness and eternal life.” Once the project was over, however, Henry returned to his discontent. Nancy was “at a loose end” again.

The truth is that Nancy Cunard and Henry Crowder were ill suited to each other. Without the attraction of racial difference, which was a powerful pull for both of them, they would probably never have come together at all. Nancy was explosive, impulsive, and conflict-driven. Henry was controlled, reserved, and profoundly averse to conflict. As she put it, he was “a most wary and prudent man . . . who often said: ‘Opinion reserved!’ Whereas to me, nothing—nor opinion nor emotion nor love nor hate—could be ‘reserved’ for one instant.” Both sought advantages from crossing race lines. Nancy almost certainly gave Henry too much credit for introducing “a whole world to me . . . and two continents: Afro-America and Africa” (considering that she had introduced Henry to African arts and culture, not the other way around). And Henry, just as certainly, gave Nancy too little credit for paving his way and making him comfortable in a “whole world” to which, otherwise, he would have had little access.

Henry disappointed Nancy politically most of all. He had no interest in politics, did not keep up with what was happening in the United States, and showed no eagerness to do so, even when pushed by Nancy. Instead of relying on Henry, she had to undertake her own self-education. Learning everything there was to know about blackness was no easy task. But she created a rigorous course of self-study, modeled on her experience as a lifelong autodidact. She subscribed to all major—and many minor—black American periodicals and had them shipped to her in France. She ordered—and sometimes borrowed—every book by black writers she could locate. Found at her death were folders of black poetry, culled from many sources and carefully retyped and filed. All were poems of militancy and protest, including Claude McKay’s famous call to arms “If We Must Die,” Will Sexton’s “The New Negro,” Paul Laurence Dunbar’s “We Wear the Mask,” and others.

Shortly after meeting Henry, Nancy wrote a poem that built on that file. She called it her “battle hymn” and dedicated it to Henry. Published in various places under the titles “1930” and “Equatorial Way,” it speaks in the voice of a black man who “says a fierce farewell” to America and threatens to “tear the Crackers limb from limb” as “vengeance . . . for the days I’ve slaved.” He heads for “an Africa that should be his”:

Go-ing . . . Go-ing . . .

. . .

I dont mean your redneck-farms,

I dont mean your Jim-Crow trains,

I mean Gaboon—

I dont mean your cotton lands,

Ole-stuff coons in Dixie bands,

I’ve said Gaboon—

. . .

Last advice to the crackers:

Bake your own white meat –

Last advice to the lynchers:

Hang your brother by the feet.

Imagining this point of view helped Nancy feel “the agonies of the Negroes.” That others might see her assumption of the man’s voice as presumptuous, even offensive, did not occur to her. To her, it made perfect sense that she could be the vessel through which “the Negro speaks.” The poem was the opening composition of Henry Music. Under various titles she republished it as often, and in as many places, as she could.

Around that time, Nancy also had a series of photographs taken by the British photographer Barbara Ker-Seymer. Though more famous photos of Nancy exist, taken by her friends Cecil Beaton and Man Ray, none of them is more interesting than the Ker-Seymer series. Ker-Seymer’s photographs are solarized, or printed in reverse, so that Nancy appears black and everything around her white. Some of the photographs depict Nancy with dozens of strands of beads wound about her long, thin neck, as if she were being lynched or strangled. In the photos, Nancy becomes not just an exotic object, a New Woman, an iconic flapper, or an icon of modernism. She becomes a “white negress,” whose agonized expressions and constrained postures signal a “bonding” with her black targets of identification.

Nancy Cunard solarized by Barbara Ker-Seymer.

Through her “battle hymn” and the photo series, Nancy was developing the politics of racial identification that would guide the rest of her life and that she had been moving toward since, as a six-year-old, she had dreamed of Africa. She had never believed that race was in the blood or biologically determined. She did not need to locate—or invent—remote black ancestors to claim a black identity. “As for wishing for some of it [blood] to be Coloured, no; that’s beyond me. That, somehow, I have NOT got in me—not the American part of it. But the AFRICAN part, ah, that is my ego, my soul.” Affiliation or affinity, not blood or lineage, Nancy felt, enabled her to “speak as if I were a Negro myself.” She was black, or partly black, she believed, because she felt herself to be so. What seemed so complicated to other people was, for Nancy, straightforward. “I like them [blacks] because I seem to understand them,” she declared. For those who truly care about others, Nancy wrote, “the tragedies of suffering humanity become as their own.” Feeling as strongly as she did about Africa meant, to Nancy, that she was part African and that giving expression to the realities of black life was her mission or calling. Volunteering for blackness seemed to her a necessary act, not an arrogant or appropriative one.

Contemporary critics have been quick to dismiss Nancy’s view as a refusal “to acknowledge her race and class privilege” and an attempt “to escape the privileged claustrophobia of her background through an identification with black diasporic and African cultures.” For that, Nancy would have probably had a ready answer. Her identification with blacks did not fail to acknowledge her privileges, she might have pointed out, but rather cost her those privileges. Once it became clear which side she was on—and she made sure that no one could be left guessing—she did not have to escape from her claustrophobic background; rather, that world firmly closed its doors to her. She welcomed that exile, moreover, actively courting it. Announcing her affiliative identity, she might have countered, had changed her identity as a white woman and made her something else.

Nancy’s challenge to available ideas of identity and race was more complex than it might seem. She was, in effect, throwing down a high-stakes gauntlet: if you did not believe that race was permanently in the blood, immutable and fixed, then on what grounds, she asked, could she be denied the right to “speak as if I were a Negro” and be “one of them, though still white”? If identity was not affiliative and voluntary, an act of desire and choice, then what, exactly, was it? Was there an alternative to affiliation that did not fall back, ultimately, on the old, worn-out ideas of essence and blood?

Nancy Cunard did not take the idea of voluntary identity lightly. It was not sufficient, she believed, to passively announce one’s identification with the Other. A person had to invite conflict and rage, had to risk being thrown out of white society for her choice. That risk taking and publicity, she believed, made a voluntary switch more than just imaginary; it put the volunteer in the shoes, to some extent at least, of those with whom she identified.

Given Nancy’s goals, a break with her family was inevitable. According to Nancy, her mother, Lady Cunard, knew of her affair with Henry Crowder as early as 1928 but pretended ignorance as long as she could. Finally, on a cold December day in 1930, at her home in Grosvenor Square, one of her lunch guests, Margot Asquith, Countess of Oxford, leaned forward confidentially across the vast dining table. “What is it now?” she asked Maud. “Drink, drugs, or niggers?” Confronted with public knowledge that Nancy had been living openly with Henry for the past two years, Lady Cunard flew into hysterics: “the hysteria caused by a difference of pigmentation,” Nancy called it. She attempted to have Nancy and Henry, then in London, arrested. She tried to have Henry deported from England to America. She enlisted friends to intercede with Nancy and beg her to leave Crowder. Finally she made it known that Nancy would be disinherited if she did not toe the line.

Nancy had no intention of toeing the line. Her first response was to make the breach as public as she could. On the basis of her mother’s response to Margot Asquith, which Nancy learned of almost immediately, she wrote an ironic essay intended to skewer all white people who believed that “friendships between whites and Negroes are inconceivable.” “Does Anyone Know Any Negroes?” rehearsed the whole episode, named all the principals, and quoted her mother at some length, sputtering foolishly: “Does anyone know any Negroes? I never heard of that. You mean in Paris then? No, but who receives them . . . what sort of Negroes, what do they do? You mean to say they go to people’s houses? . . . It isn’t possible. . . . If it were true I should never speak to her again.” Maud is portrayed as a racist and a fool, an unsophisticated bumpkin. Nancy prepared the essay for publication in The Crisis, where it would attract attention. Strangely, the essay had little impact on its intended audience; apparently it was read by very few whites and none at all in England.

Nancy was spoiling for a fight. She was determined that her break with her family and her new identity both be noticed. In early 1931, she republished her “battle hymn” on “The Poet’s Page” of The Crisis alongside other poems by white women about race, including “A White Girl’s Prayer” by Edna Margaret Johnson and “To a Pickaninny” by Edna Harriet Barrett. She also threw her support to a film that the press had described as “the most repulsive conception of our age” and that the growing European fascist parties were singling out as an example of modern decadence. L’Age d’Or, by the surrealists Luis Buñuel and Salvador Dalí, offered a number of vignettes that included a woman fellating a statue’s toe, priests copulating with prostitutes, defecation, and infanticide. The film was banned in France after French fascists attacked screenings. Nancy succeeded in arranging a one-night London screening of a smuggled copy. As she well knew, her mother’s British friends at the time encompassed all the key players of the growing British Union of Fascists, including Oswald Mosley—“The Leader”—and his future wife, the former Diana Mitford, who was just then preparing to leave her husband, Bryan Guinness. It would have been impossible for Nancy’s mother or any of her circle to be unaware that Nancy’s screening was aimed at them. For Nancy it was a relief to be able to dissociate herself publicly from her mother’s right-wing leanings.

Feminists in the 1960s coined the phrase “The personal is political.” Nancy Cunard, from the 1920s on, lived by a reverse formulation that said, “The political is personal.” In spite of a deeply loyal nature that could—and did—forgive many personal slights from her friends, she could not bear reactionary politics in those she knew. “She was democratic [about people] to the point of insipidity,” one friend remembered, unless they revealed reactionary politics. “If ever she disliked or hated anyone, the cause was political.” She never, for example, got over how someone “so hyper-sensitive,” so gifted, and so “very human [a] kind of person” as Ezra Pound could have become a fascist. “Totally baffling,” she said.

As the “smarming twenties” tumbled into the thirties, Nancy, still “at a loose end,” continued trying to get her bearings. Running a press, even one as illustrious as The Hours, having affairs, and scheduling scandalous screenings were not getting her the “contact” she wanted. She was restless and itchy, sure of herself but unsure of where to go. She knew that she wanted “to work on behalf of the colored race.” Now she needed a cause. A good fight.

![]()

I intend to devote my life to . . . the Colored Race.

—Nancy Cunard

The Scottsboro case had an electric effect on Nancy Cunard. She was stunned by the “collective lunacy” of the “lynch machinery,” which seemed intent on sending the Scottsboro Boys to their deaths for crimes that had never occurred. She published a poem called “Rape,” which she dedicated “To Haywood Patterson in jail, framed up on the vicious ‘rape’ lie, twice condemned to death, despite conclusive and maximum proof of his innocence—and to the 8 other innocent Scottsboro boys.” Like Josephine Cogdell Schuyler in “Deep Dixie” and Annie Nathan Meyer in her play Black Souls, Nancy was looking at the underside of the myth of the black rapist—the unspeakable and usually unspoken truth that some white women desire black men. In “Rape,” a desolate farmer’s wife, on a restless rainy day, tries to seduce one of her husband’s black workers and is rejected by him. Humiliated and furious—as angry with herself as with him—she charges him with rape. She used exactly the language with which the Klan threatened Nancy in 1932—“Your number’s up”—to spread her deadly lies: “And they cotched him in the swamps / And what the hounds left they hung on a tree.” Sympathetic at first toward the wife’s boredom and sense of entrapment, “Rape” ultimately places her within a southern history where “‘the lady of the house’ was honoured” as “nobody’s nigger” is lynched. That was the history uppermost in Nancy’s mind as the Scottsboro Boys were tried over and over again, and convicted every time. The charges against the defendants were ridiculous, but, as Nancy Cunard put it, “not unparalleled.” She was filled with “the indignation, the fury, the disgust, the contempt, the longing to fight.”

By 1931, Nancy’s politics had increasingly become aligned with the Communist critique of class relations, capitalism, and race, though she never became a Communist. She appreciated the way in which the Party drew attention not only to the Scottsboro Boys and their plight but also to the tens of thousands of unemployed Americans then hopping freight cars in search of work, sometimes crowding into the cars so thickly that, as one former hobo recalled, “it looked like blackbirds.” She especially appreciated the way the Communist Party, unlike the NAACP, stressed militancy over manners, insisting that racism made the usual social niceties irrelevant and even immoral. At the heart of the fight between the NAACP and the Communist Party’s legal wing, the International Labor Defense (ILD), was a fundamental disagreement about what social rules did—and did not—apply when whites were called upon to confront the violence and race hatred within their own ranks. At stake as well was a strategic question about how militant a stand blacks could take in fighting for their rights—the very question that was then splitting the new and old guards of the Harlem Renaissance.

Nancy had experienced a lifetime of social niceties inside the gray stone walls of Nevill Holt. Without a very high degree of civility, certainly, her mismatched parents could never have stayed together. Good manners and emotional reserve, rather than frankness or intimacy, were her parents’ highest values. Nancy came to associate civility with hypocrisy and militant outspokenness with authenticity. She set particular store by militancy. “It is only by fighting,” she wrote, “that anything of major issue is obtained.” Fighters, she declared, “are pure in spirit.” She also set great store by honesty and distrusted anything that smacked to her of window dressing. “The facts please,” she would say to her friends, “without any hooly-gooly.” One friend remembered her as an “extremist in words,” who “never hesitated to express herself with the utmost frankness about anything.” That is not to say that Nancy Cunard was unmannered. In fact, she had impeccable, “delightful manners” and always recoiled sharply from any crudeness of speech or behavior in others; this attitude was an asset in black society.

The NAACP at first was tepid in its response to the Scottsboro arrests and trials. That was not merely caution “to avoid antagonizing Southern prejudice,” as the journalist Hollace Ransdell surmised. Mary White Ovington and other NAACP officials wanted to make certain that there was nothing to the rape charge at all—no sexual contact between parties—before leaping into the case. With its credibility and connections resting on respectability and reputation, the NAACP felt justified in being selective. Nancy Cunard and others were outraged. It was clear to her that the charge of rape was nothing more than “terrorisation of the Negroes.”

The NAACP had stood up to years of criticism that it was an organization founded and run by outsiders, such as Mary White Ovington. In turn, its leadership was very sensitive to what it saw as outsiders using the black community for their own agendas and interests. Ovington kept mostly quiet on that score, but Walter White and William Pickens both accused the Communist Party of using the case to recruit members and of being “pig-headed” about the complexities of race. Some black papers also doubted that the Communist Party “would make saving the boys’ lives its top priority,” seemingly clearing the way for the NAACP to take leadership of the case. But the NAACP gave the defendants confusing advice and failed to elicit their mothers’ support—a crucial error that turned the case over to the Party and its ILD.

Ovington and others at the NAACP, moreover, underestimated the attention the Scottsboro case would receive. To them, the case was not unique. As early as 1906, Ovington had written about the “ghastly truth that any unscrupulous white woman has the life of any Negro, no matter how virtuous he may be, in her hand.” The power that Bates and Price were wielding was horrific but not new. Instead, she worried about “the nasty propaganda potential of any event with white women and black men.”

Nancy Cunard and Mary White Ovington squared off on the Scottsboro case chiefly over their views of the need for caution (Cunard couldn’t abide it). Whereas Nancy sometimes traded on her singularity to get her own way (she knew that black male comrades such as Walter White and W. E. B. Du Bois would certainly not try to tell a British heiress how to behave), Ovington courted respectability, which she aligned with being as invisible as possible. From her perspective, the less attention she drew to herself, the more she could build a life that otherwise would have been unthinkable for a woman of her background.

In 1929, the Communist Party made “the struggle for Negro rights” one of its central priorities and sent many whites into black communities, Harlem especially, as organizers. To encourage black recruits and rout out organizational racism “branch and root,” interracial socializing was encouraged. White Communists found guilty of “white chauvinism” were publicly tried in open hearings intended to shame them into “the greatest degree of fraternization.” Party organizers offered dancing classes to white male organizers so that they would not be ashamed to ask their black female comrades to dance. If Nancy had any pity for the humiliated white organizers, she must have felt even more keenly her own superiority to those slow-learning whites. She supported the Party’s insistence that foot-draggers change immediately and absolutely. “The Communists,” she wrote admiringly, “are the most militant defenders and organizers that the Negro race has ever had.” She credited the Party with “putting a new spirit into the Negro masses” and teaching them to “fight.”

During the Great Depression the Communist Party gained ground in Harlem. Its advocacy of militant political protest made it stand out in its approach to local issues. “Throughout the 1920s, Harlem political leaders, even those renowned for their militancy, rarely employed strategies of confrontation and mass protest to achieve their goals.” Langston Hughes, activist and Hampton Institute teacher Louise Thompson, and a few others felt that the Communists were an alternative to the Negrotarians. (Thompson married Party lawyer William L. Patterson after a brief, disastrous marriage to Wallace Thurman.) But its centralized authority, lack of flexibility, and attacks on well-respected blacks, such as W. E. B. Du Bois, alienated many in Harlem. Its highly unusual interracial policies created considerable controversy. Numerous black men who became associated with the Communist Party in the 1930s—such as Theodore Bassett, William Fitzgerald, Abner Berry, and James W. Ford—had white girlfriends or wives. The weekly Amsterdam News accused the Party of using white women as “Union Square blondes and brunettes” to seduce “Harlem swains” into communism. According to Claude McKay, a group of black Communist women, led by Party member Grace Campbell, felt strongly enough about it, in the 1930s, to ask that the Party take a stand against this “insult to Negro womanhood.” McKay noted that it was not a subject blacks were generally willing to “air.” Campbell’s group was a particularly “bitter lot,” he said. Nancy did not see what all the fuss was about.

It is possible that the Party’s interracial program, called “black-white unity,” resonated with Nancy’s thinking. At the heart of much of Harlem’s cultural politics—from Marcus Garvey’s back-to-Africa movement to the “Don’t buy where you can’t work” boycott initiative—appeals to “race loyalty” were meant to galvanize support by capitalizing on feelings of loyalty and shared oppression. It was an effective appeal, with many successes to its credit. But it did not include whites, even Nancy Cunard, except as bystanders and observers. She called race loyalty “the wrong kind of pride; a race pride which stopped at that . . . race conscious in the wrong way.” The Party stressed worker solidarity, not race pride. And it formulated an active critique of the ideology underlying race loyalty as divisive and mystifying. The Party attacked the “timidity” of the NAACP and the Urban League, going so far as to call them “agents of the capitalist class,” in the context of the simmering debate over appeals to identity politics. The question of what role whites could and should play in Harlem and in black political struggles more broadly was embedded in those debates. The less one cleaved to an idea of race loyalty—in any of its permutations—the less of a problem it was to have whites in Harlem or in leadership roles in Harlem politics. A principled opposition to the concept of race loyalty helped obviate questions of appropriation, theft, or inappropriate behavior by whites. Though she stopped short of becoming a Communist—Party discipline was out of the question for her—Nancy sympathized wholeheartedly with the Party’s racial ideology, its attack on “Negro bourgeois leaders” as “white man’s niggers,” its challenge to the politics of identity, and its welcome of white activists.

The Scottsboro case brought more white women into black politics: writers such as Annie Nathan Meyer, Muriel Rukeyser, and Hollace Ransdell, as well as activists, Communist and other. That meant that the question of the role white women could play, and the possible damage that their mere presence could pose, was on the table, albeit sometimes in ways that only insiders would have been aware of. Nancy was keenly aware of the myriad ways in which the increased presence of white women provoked debate.

She took the position of honorary treasurer of the British Scottsboro Defense Fund: marching and organizing, circulating petitions and flyers, making banners, sponsoring fund-raisers, and encouraging her friends to write poems about the case that could be used in the cause. She also contributed her own money, when she had any, sometimes sending cash to the defendants and their families and encouraging her friends to do likewise. She was determined to make the Scottsboro case more visible in Europe.

One July Fourth, she threw a fund-raiser that drew enormous publicity as “one of the most spectacular and curious parties that can ever have been held in this country.” Capitalizing on the 1920s suntanning craze, with all the Negrophilia it implied, Nancy threw a sun-ray bathing and dancing party, taking over a swimming pool and a dance floor inside one of London’s best hotels. There she created an imaginary resort, where blacks and whites mingled to bathe, dance, talk, and get to know one another. London’s Daily Mail described the party as “tropically hot” and “exotic,” noting breathlessly that “Negroes of all shades of colour were dancing with white women.” One London paper imagined that Nancy’s behavior must mean that she “hate[s] so many white people.” The suntan party drew attention from as far away as Pittsburgh, Canada, South Africa, Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), and Jamaica. One Jamaican paper noted with approval that “Miss Cunard’s attitude towards the Negro race has estranged her from her mother, and has robbed her of many friends, while it has gained her new ones.”

Nancy did make new friends through the Scottsboro case, realizing some of her ambition both to find “an American white friend with feelings such as mine” and to establish “contact” with blacks. She was in touch with some of the fellow travelers who were also working on the case. In her papers is a warm letter from Josephine Cogdell Schuyler, certainly someone with feelings “such as” Nancy’s. (Unfortunately, like many on the left who watched his rightward swing with alarm, Nancy came to see George Schuyler as a political “scoundrel,” making further friendship with his loyal wife impossible.) She corresponded with many of the defendants themselves and also with their mothers. Haywood Patterson, who was treated particularly harshly by the Alabama courts, wrote to Nancy about his “unbearable” conditions, his determination “to keep bearing on,” and her “comforting” letters to him. He also urged Nancy, who was notoriously heedless of her own health, to take care of herself and get enough rest, something that even Nancy’s best friends dared not suggest to her. Through the Scottsboro case Nancy befriended a number of other prisoners, including one James Threadgill, a “Negro lifer” to whom she wrote and sent books for two decades. “Dearest,” Threadgill wrote in 1954, “this I hope will find you feeling well and doing just fine.” Again she demonstrated her ability to identify with those who were very different from her. “I’m not really thinking of anything else but them [the Scottsboro Boys] all the time,” she wrote to a friend.

Six days after the Scottsboro Boys were arrested and the day after all nine were indicted, Nancy decided to travel to the United States. She also decided to create a document that would tell the truth about race and drafted plans for a massive book to record and celebrate everything that “is Negro and is descended from Negroes.” It would be, she said, “the first time such a book has been compiled.” She was “possessed,” she later wrote, by “a new idea” of what to do and how to live.