Be careful about what you call

“good” and “bad”

The words we use to describe something affect how we feel about it. Leela is fond of “horrible” to describe when something goes wrong, but “great,” “amazing,” or “awesome” when she enjoys it. She’s had a “horrible” month, but recently things have been looking “great”! These words are accompanied by big emotions, both positive and negative. The Stoics claim that this isn’t a coincidence. This week, you’ll see for yourself if they’re right.

"True happiness, therefore, consists in virtue: and what will this virtue bid you do? Not to think anything bad or good which is connected neither with virtue nor with wickedness.”

Seneca, On the Happy Life, 16

Evaluating circumstances that happen using strong value judgments can lead to strong emotions, as in Leela’s case. When Leela uses value-laden words such as “great” and “horrible” in describing her experiences, she’s not just reporting on facts. It isn’t a simple fact that her last month is “horrible”—horribleness is not out there in the world—it’s a value judgment that exists in her mind. On top of that, using strong words when we evaluate things can fire up our emotions in a vicious cycle; the words we use to describe them can make us feel more strongly about the thing we are describing. This is one reason why Seneca advises us to call only virtue “good” and vice “bad.” Virtue and vice are the main things we should feel strongly about, as they’re the most valuable things in life. Everything else should come after.

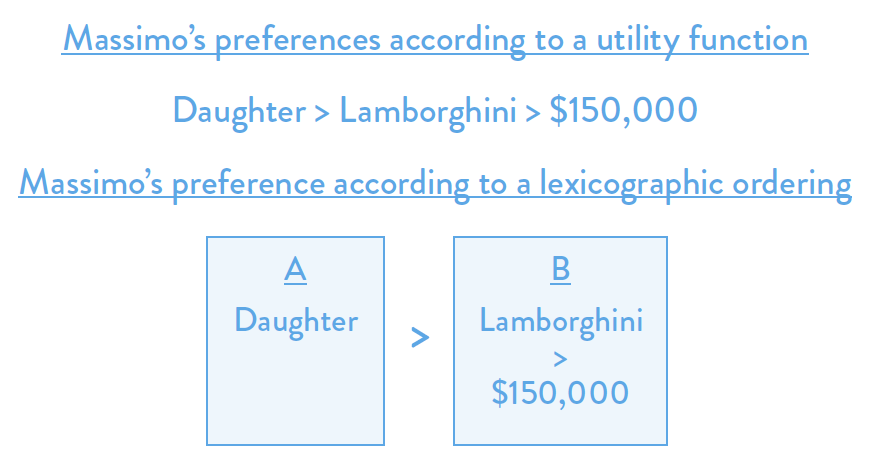

The type of preference ordering in which one set of things ranks more highly than others is known to modern economists as lexicographic preferences.1 This is much like sorting things in alphabetical order. We start with all words that begin with A first, then sort again within that class, then proceed to the letter B, and so on. Our preferences can behave in the same way; we group items in an A class, then move on to the B class, and so on. Things in our A set are always more important to us than things in our B set, which in turn outrank all things in our C set. Crucially, we are not willing to trade members of the A set for members of the B set.

Here’s an example: Massimo loves his daughter, who is in his A set. He also happens to love Lamborghini cars, which are in his B set. If Massimo had a lot of money (also in the B set), he would gladly trade $150,000 of it for a Lamborghini, particularly an orange one. Since he’d be willing to trade at least some amount of money for a Lamborghini, it suggests that they belong in the same set. And the fact that he’d pay up to $150,000 for a Lamborghini suggests he values the Lamborghini more than that amount of money (but only if it’s orange!). But no way on earth would Massimo ever trade his daughter for a Lamborghini. That’s not because it would be illegal (although it is), but because these rankings truly reflect his values, and those values are lexicographic to an extent. Studies have found that people sometimes order issues on the environment lexicographically,2 especially if they view environmentalism using a deontological (duty-based) ethical viewpoint.3 Other research suggests that lexicographic ordering extends beyond environmentalism, into other areas of preference.4

If all this seems confusing, take a look at the following diagram.

Now, the ancient Stoics thought that virtue (or to be more precise, the four virtues: practical wisdom, justice, courage, and temperance, which we’ll explain further in Week 11) ought to be in our A set. Everything else is in the B set. The things that Leela feels she should be happy about, therefore, are in the B set: her relationship, good times she has with friends, and her job. Could it be that she does not feel satisfied because she hasn’t taken good care of the A set—that is, she has not been virtuous?

The Stoics went one step further than modern behavioral economists, arguing that things in the B set are not really good, they are just preferred (other things being equal). Likewise, if we do not have those things, it isn’t really bad, it is just dispreferred. Since these are outside of our control and not necessary for our happiness, they are known as preferred and dispreferred indifferents. Virtue is the only thing in the A set, because it is the only true good. It follows that acting unvirtuously is the only true bad.

The Stoics inherited this essential idea from Socrates, who defends it in the Platonic dialogue Euthydemus (from the name of a Sophist with whom Socrates is talking). Socrates argues that the only thing that can always benefit us is virtue, and the only thing that can truly hurt us is the lack of virtue. But wait a minute, you might say. Surely wealth, power, or fame is also good, no? Not really. They may be used for good or for bad. Being wealthy may be a conduit for doing good for humanity, but it may also be what enables you to do harm. The same goes for all the other preferred or dispreferred things. As Epictetus puts it: “What decides whether a sum of money is good? The money is not going to tell you; it must be the faculty that makes use of such impressions.”5 That faculty is reason, which tells us that virtue is the only true good.

There’s one more step to understand why Leela experiences big variations in her emotions due to changing external circumstances. Seneca suggested that true happiness consists in virtue. That’s because external circumstances, such as a job, friends, and even relationships come and go in life, so if we let our happiness depend on these circumstances, we risk being constantly at the mercy of luck or of other people’s decisions, which we cannot control. Note that all the things that Leela values are external; they are subject to the whims of fate. Virtue, however, will always repay us. It is always firmly within our control. If Leela aimed to call only virtue “good” and vice “bad,” and remove value judgments involving external things outside of her control, she would have a much more peaceful mind, the Stoics would claim. This week, you’ll test this hypothesis for yourself.