PREFACE

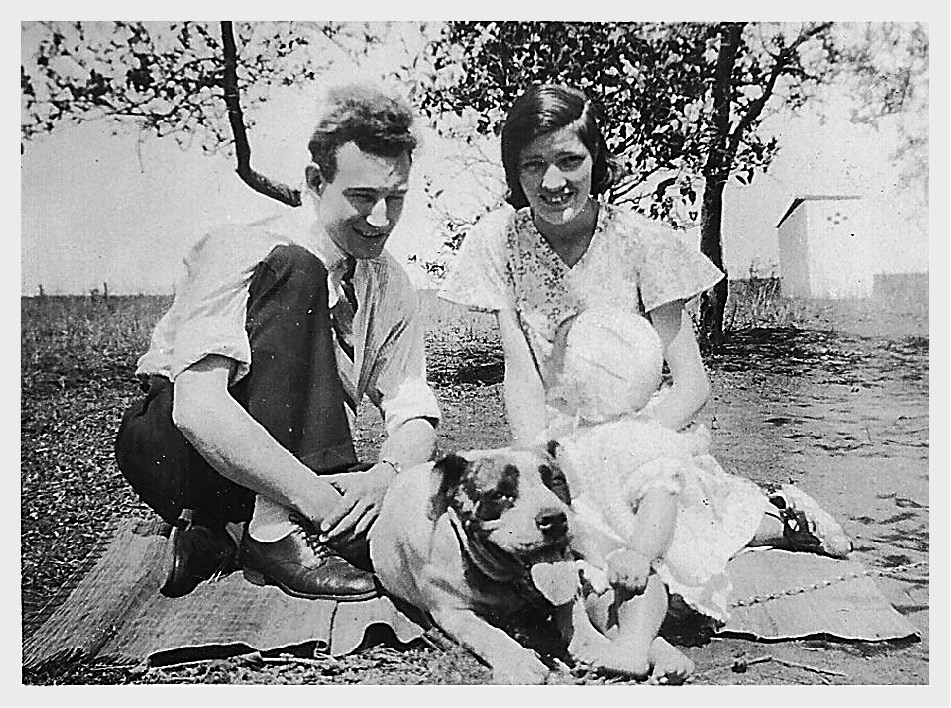

“We three” and Bonza the dog; it annoyed my mother that in the only photo of her and her parents in existence, you couldn't see her face.

MY GRANDMOTHER THOUGHT she was marrying someone vibrant and exciting, a man with wavy hair and tremendous energy. He was a talented carpenter, a talented artist, a convicted murderer, and a very bad poet. He spent his working life as an engine driver and down the gold mines, and when he met my grandmother, sometime in the early 1930s, he was probably employed at the railway station she passed through en route to her office training course.

My mother said two things about this man: that he was “very clever” and that he was “very peculiar.” She also said he had a faulty sense of humor—he liked slapstick—which was her backhanded way of calling him Afrikaans. I gather he was vain about his European origins.

At the time my grandparents met, my grandmother was being courted by someone else, a man called Trevor, or “Bessie Everett’s brother Trevor” as the family on that side remembers him, which is to say, as a known quantity. Nice Trevor, boring Trevor; I picture him in a cardigan, smoking a pipe and reading the less-interesting bits of the daily newspaper. By all accounts, my grandmother and Trevor stepped out only a few times. The fact he still rates a mention, some seventy years on, is because in the story that follows Trevor became the shining symbol of what might have been.

She was called Sarah Doubell, and, like everyone who dies young, is supposed to have been beautiful. She had long dark hair, pale skin, big brown eyes, and slender ankles. She would get “stopped on buses,” said her older sister Kathy, and asked out by men of superior backgrounds. Before they moved to the coast, her family had been skilled laborers on the ostrich farms, and in group photos, where her siblings look solid, agrarian folk in stout boots and triangular smocks, Sarah seems always to be in floaty dresses and unsuitable footwear. She didn’t marry Trevor. She married the other man, at the Babanango Court House, in the presence of her sister Johanna and her brother-in-law Charlie, and moved to a cinder-block house somewhere out in the country. They came into town for the birth of the baby.

There is a single photo of that brief family, sitting on a picnic mat outside in the sun, the father in a shirt and tie, the mother in a pretty dress, and the baby in a bonnet looking up at her father. A bulldog pants in the foreground. “‘We Three’ and Bonza,” Sarah has written on the back, the “We Three” in quotation marks, as if she is poking affectionate fun at them, a conspiracy of happiness against the rest of the world. I assume they were happy and that my grandmother didn’t know about her husband’s murder conviction. Which is a shame. It would have been useful information to have had when, as she lay dying, she was deciding with whom to leave my two-year-old mother.

For a few years after her death, Sarah’s family stayed in touch with the husband. They were relieved to hear he’d remarried. And then one day he was gone. It was almost forty years before the family tracked down the baby, by which time she was living in London and married to my dad. Her cousin Gloria, Kathy’s daughter, sent her a letter introducing herself as a member of her mother’s family and asking where she had been all those years. I wonder now how my mother replied.

• • •

MY MOTHER DIDN’T TALK much about her past when I was growing up. I knew she had emigrated to England from South Africa in 1960 and, in the intervening years, had been back twice. I had met none of her seven siblings and could name probably half of my sixteen first cousins. There were a few stories: about her childhood, her work, her friends, which for the most part she made sound fun. She also hinted at another history, behind the official version, which sounded less fun and which for a long time I was happy to ignore. It was only when she was dying that she told me anything specific. When she was in her mid-twenties, she said, she’d had her father arrested. There had been a highly publicized court case, during which he had defended himself, cross-examining his own children in the witness box and destroying them one by one. Her stepmother had covered for him. He had been found not guilty.

I was calm as she told me this, as I had not been on the one previous occasion she had tried to bring it up. Along with everything else going on, I filed it away to think about later, but as tends to happen, later came sooner than expected.

Six months after my mother’s death, I flew from London to Johannesburg to try to piece together the missing portions of her life. It is a virtue, we are told, to face things, although given the choice I would go for denial every time—if denying a thing meant not knowing it. But the choice, it turns out, is not between knowing a thing and not knowing it, but between knowing and half knowing it, which is no choice at all.

Even after I discovered the real story, I was still evasive about it, to myself and others. When someone suggested, during the course of writing this book, that I read the “clinical literature,” I was outraged. I didn’t want my mother reduced to the level of case study. I didn’t want to lump her in with all those terrible people moaning on about themselves, going on talk shows to weep and wail. I objected to the language they used: “survivors,” as they sometimes called themselves, seemed to me to be a term that only underlined their victimhood. The notion of “survivordom” had, in any case, become so prized in the culture, so absolving of all behavior resulting from the initial trauma—so completely, narcissistically inviting—that those without very much to survive these days rummage around until they come up with something.

“Hard-hearted Hannah” my mother sometimes called me. Mimics frequently get the style but not the heart of a performance right.

Above all, I didn’t want to give up the memory I had of her and replace it with something skewed and pathologized. My greatest fear, when I started this, was that I would undo all her good work. Finally, one day, during the endless displacement activities one undertakes while writing a book, I bought a research paper online. It was a study by Canadian psychologists into the parenting deficits of women with “girl children” who in their own childhoods had been the victims of extreme sexual and physical violence. There were the well-known repeated behavioral patterns. There were high instances of alcohol and drug dependency. It was the interviews with women who had not gone on to abuse their own children that shook me the most, however. Excerpts from these women’s interviews catalogued the worry they had about overprotecting their children. They saw danger everywhere; they talked about the suspicion of every male who came into contact with their daughters, including their husbands, and the strain this put on their relationships. They talked about the intense pressure they felt to control the environment around their children and of the need to make their children invincible. In the most heartbreaking terms, they talked about the desire to keep them safe without making them crazy. Meanwhile, they had no way of helping themselves.

My mother wasn’t a great one for asking for help. She would rather do something herself than have someone else do it for her. Toward the end of her life, she reluctantly accepted she might need some practical assistance, without ever quite relinquishing the upper hand. When a nurse came from the hospice, my mother extracted her life story and started ringing rental agents on her behalf. When neighbors came around with soup and fans, she smiled as if doing them a favor.

An enormous effort went into maintaining this idea she had of herself, and of me, and there were times when I thought I could see the mechanism at work. It had a hint of the burlesque about it, all her positive thinking. As a child, it annoyed me. “OK, OK,” I thought, “I get it.” Her genius as a parent, of course, was that I didn’t get it at all. If the landscape that eventually emerged can be visualized as the bleakest thing I know—a British beach in winter—she stood around me like a windbreak so that all I saw was colors.

A therapist once described my mother’s background in relation to my own as the elephant in the room, a characterization I reacted strongly against at the time. And my dad did too, when I told him. I have no idea what my mother did with the elephant, but most of the time it wasn’t in the room with us. And so, while I strain to find an explanation for just how a person can live one kind of life to the age of almost thirty and then, witness-protection-like, cut that life off and begin again, I have no real answer. Friendship helped. And humor. Beyond that, all I can say is, it was an effort of will.

She never got any credit for it. Her aim—to protect me from being poisoned by the poison in her system—depended for its success on its invisibility. “One day I will tell you the story of my life,” she said, “and you will be amazed.” She never did, not really, although I think she wanted to. So I went to find out for myself. It’s amazing. Here it is.