Indigenous Subsistence Patterns of the Hudson Bay Lowlands and Northern Plains

In order to analyze continuity and change in Aboriginal peoples’ use of big game hunting and military technology, their subsistence patterns, modes of conflict, and social organization at the time of contact need to be understood. Various sources contribute information on these topics. For the Northern Plains and Subarctic there are various Indigenous sources of information that have been transmitted orally. Some of these reach back into the times before contact. Others explicitly deal with the changes brought on by the adoption of European technology.

Furthermore, fur traders like David Thompson and Peter Fidler traveled through the Central Subarctic, as well as the Northern Plains, on their way from Hudson Bay to trading posts, leaving ethnographic accounts about the Aboriginal peoples they encountered. The first accounts of European outsiders about Hudson Bay and the Subarctic provide information on Aboriginal lifestyles and technology that, within reasonable limits, can be extrapolated to conditions just before contact.

For the Plains this is more difficult, because some European goods, especially metal weapons and firearms, reached Aboriginal peoples in the Plains through Indigenous trading networks before the first Europeans arrived, already contributing to technological change before the process could have been observed by Europeans.

Archaeological information also contributes toward a more complete understanding of Aboriginal peoples’ lives around the time of contact. The remains of Aboriginal settlement sites and camps allow us to draw conclusions about dwellings and social organization. Artefacts and refuse reveal Aboriginal subsistence patterns, diet, hunting methods, and technology. The forensic analysis of human remains can provide insight into Aboriginal peoples’ physique, the state of their health, and their lifeways.

To understand Aboriginal peoples’ subsistence strategies, a closer examination of the geography, climate, flora, and fauna of the Central Subarctic and Northern Plains is necessary. The ecological and cultural boundaries between these two regions were fluid. The Northern Plains are connected to the northern boreal forests by a Parklands zone, a belt of patches of forest, brushlands, grasslands, and lakes. People from the Plains and Central Subarctic utilized this Parkland region. Thus, it is difficult to draw sharp distinctions, especially for the Western Cree, some of whom moved back and forth between these different ecological zones and thus adopted cultural traits reflecting all these regions.1

Central Subarctic

For the purposes of this study, “Central Subarctic” refers to the west coast of James Bay, the south and west coast of Hudson Bay, and the northern halves of the modern provinces of Manitoba and Saskatchewan. In the mid-nineteenth century, Aboriginal peoples living in these areas were the Algonquian-speaking Swampy Cree (Omushkego) and Rock Cree (Asiniskawidiniwak), and the northern Ojibwas or Saulteaux. To the north of these groups lived various Athapaskan-speaking peoples (Déné), such as the Chipewyan.

David Mandelbaum and other early twentieth-century scholars stated that Cree people had expanded westward with the fur trade in search of new and untapped fur resources. In this process they were said to have gained an alleged military superiority through firearms and edged metal weapons acquired from fur traders, thus enabling them to displace or subdue other western Native peoples. Based on an analysis of fur trade records in regard to the location and seasonal movement patterns of Cree-speaking peoples, Dale Russell and James G. E. Smith were able to disprove this notion and demonstrate that Cree-speaking peoples had been living in the Subarctic-Parklands area from the west coast of Hudson Bay as far west as eastern Alberta well before the beginning of the Hudson Bay fur trade.2 Linking archaeological evidence to fur trade documents, David Meyer argued that by the late 1600s, Cree-speaking peoples occupied much of what is now central Manitoba and Saskatchewan into eastern Alberta. Residing to the south of them, as far west as south-central Saskatchewan, were various groups of Assiniboine. Their immediate western neighbors were Blackfoot and Gros Ventre peoples.3

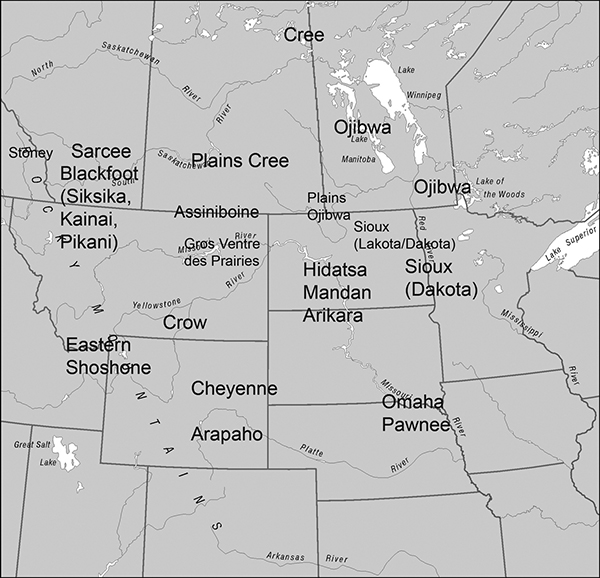

Map 1. Approximate locations of Aboriginal peoples in the Hudson and James Bay Lowlands and surrounding area during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century. Base map by Weldon Hiebert, Department of Geography, University of Winnipeg.

In 1694 the Jesuit missionary Father Gabriel Marest traveled the region near the mouth of the Nelson River, probably wintering there. His description of the area contains information that is crucial to understanding the challenges Aboriginal people faced in their subsistence efforts:

The fort is near latitude 57 degrees and situated at the mouth of two beautiful rivers. But the soil is very barren. The country is marshy with many wet meadows. There is little wood and what there is, is very stunted. Within thirty or forty leagues of the fort there is no heavy timber. That is caused, no doubt, by the violent sea winds which are usually blowing, the great cold, and the almost continual snows. The cold begins in the month of September and is then severe enough to fill the rivers with ice and sometimes to freeze them quite over. The ice lasts till about the month of June, but the cold does not cease even then. It is true that during that time there are very hot days but not for long (for there is little intermediate between great heat and great cold). The north winds, which are frequent, soon dispel this early heat and often, after perspiring in the morning, you are frozen in the evening. The snow lies on the ground eight or nine months but it is not very deep. The greatest depth this winter has been two or three feet.

The long winter, although it is always cold, is not, however, equally so at all times. There are often, in truth, excessively cold days, on which one does not venture out of doors without paying for it. There are few of us who have not borne the marks of this extreme weather; and, among others, a sailor lost both his ears, but there are also fine days. What especially pleases me is the absence of rain and that, after a snowstorm or blizzard (or poudrerie, as a fine snow which penetrates everywhere is called) the air is pure and clear. If I had to chose between winter and summer in this country I do not know which I should prefer, for, in summer, besides the scorching heat, the frequent changes from extreme heat to extreme cold, and the rarity of three fine days on end, there are so many mosquitoes or black flies as to make it impossible to go out of doors without being covered and stung on all sides. The flies are more numerous here and stronger than in Canada. Add that the woods are full of water and that there is no going far into them without going up to the waist.4

Marest’s description closely resembles that of the French military officer Bacqueville de la Potherie, who participated in a French naval expedition to capture and destroy the English bayside fur trade posts in 1697.5 Both descriptions emphasized the long winters, the extreme cold, and the abundance of biting insects in the short, hot summers. These conditions were crucial in shaping the migratory patterns of animals, notably caribou, which formed the basis for the subsistence patterns of Aboriginal peoples. In the summer the swampy and marshy ground limited travel. The scarcity of wood and its stunted growth placed severe restrictions on Aboriginal peoples’ options for the manufacture of wooden tools and weapons.

Just as it was three hundred years ago, marshy wetlands still dominate the James Bay–Hudson Bay Lowlands but are interspersed with more forested pockets.6 On the coastline a thin strip of tundra vegetation extends from about the mouth of the Churchill River to the northern shore of Akimiski Island in James Bay. This tundra area provides a favored habitat for caribou and other lowland animals.

Much of the Subarctic is characterized by a “continental” climate, with short summers and low winter temperatures. Fewer than four months have a mean temperature higher than 10 degrees Celsius. In the central Hudson Bay Lowlands, mean daily temperatures reach up to 15 degrees in July, dropping to minus 25 degrees or lower in January. The maximum frost-free period is 100 to 120 days per year in the regions west of Lake Superior and along the boundary between the boreal forest and the plains-parklands environment stretching across the continent. For the Central Subarctic a frost-free period of forty to sixty days is more typical.7

Coniferous trees characterize the vegetation in most of the Subarctic. Moisture conditions, temperature, and wind determine the species present in any given location, but the level of species diversity is relatively low. Coniferous trees dominate the vegetation of the upland forests. White spruce (Picea glauca) is the most common tree in the boreal forest and is found in well-drained sites and on south-facing slopes. Black spruce (Picea mariana) and tamarack (Larix laricina) inhabit relatively wet sites. Balsam fir (Abies balsamea) and jackpine (Pinus banksiana) occur as well.8 The few species of deciduous trees, such as birch (Betula papyrifera), poplar (Populus balsamifera), and aspen (Populus tremoloides), grow in limited numbers throughout the Subarctic.9 The paper birch is absent from the lowland region. The most common trees in the lowlands are spruce, tamarack, and willow.10 Several shrubs and dwarf shrubs such as dwarf birch (Betula glandulosa), crowberry (Empetrum nigrum), alder (Alnus crispa), and labrador tea (Ledum groenlandicum) are found in the tundra and transitional areas.11

Massive herds of barren-ground caribou (Rangifer tarandus groenlandicus) at one time migrated along the coastal strip of tundra vegetation of the Hudson Bay Lowlands in summer to feed and calve. Besides the migratory barren-ground caribou there were also indigenous woodland caribou (Rangifer tarandus caribou) in some of the more forested areas and in the boreal forest of the uplands.

Moose (Alces alces) were rare in the Hudson Bay Lowlands. Moose populations in the uplands adjacent to the coastal lowlands declined during the fur trade period, disappearing entirely by the early nineteenth century. However, moose populations have increased over the past 150 years. These animals now frequent the lowlands all the way to the coast.12

The population of snowshoe hares (Lepus americanus) in the area provided an important source of food and raw materials to local Indigenous people, but it was subject to extreme fluctuations. After reaching a peak every nine or ten years, the population would suddenly decline sharply.13 Besides hares, Aboriginal people hunted other rodents for food and furs, including beaver (Castor canadensis), muskrat (Ondatra zibethicus), and the hoary marmot (Marmota caligata, also known as groundhog), porcupines (Erithizon dorsatum), and arctic ground squirrels (Spermophilus undulates).14

Marshes along the coast provided seasonal gathering and feeding places for large numbers of waterfowl, such as Canada geese (Branta canadensis), Richardson’s geese (Branta canadensis hutchinsii), lesser snow geese (Anser caerulescens caerulescens), blue geese (Chen caerulescens), and various kinds of ducks and swans.

Of the numerous fish species in the lowlands’ rivers and lakes, the lake sturgeon (Acipenser fulvescens), northern pike (Esox lucius), also called jackfish, and various kinds of sucker were important food sources.15 Black bears (Ursus americanus) and polar bears (Ursus maritimus) were occasionally hunted for their hides and also to some extent as a food source.16 White or beluga whales (Delphinapterus leucas) and harbor seals (Phoca vitulina) were of some importance as a source of food to the Hudson Bay Lowland Cree, but more so as sources of raw materials, such as sinew and hides for cordage.17

Subsistence Activities of the Omushkego Cree around the Time of Contact

Oral traditions of the Omushkego Cree in the Winisk region maintain that their ancestors lived along the Winisk River and its tributaries long before the arrival of Europeans there.18 Archaeological evidence documents prolonged human habitation in the region before contact.19 For example, a fishing site on the Shamattawa River, which flows into the Winisk River, has yielded the earliest recorded date for year-round human habitation in the Hudson Bay Lowlands, with a radiocarbon date of 3,920 plus or minus 180 years before present.20

Despite a seasonal abundance of game animals, the Hudson Bay Lowlands are a challenging environment with a limited capacity to sustain large groups of people for extended periods in a single location. Therefore the local population has been small and has had to disperse over vast areas for a substantial part of each year. The Hudson’s Bay Company officer Andrew Graham stated in the 1770s, “I am certain that the total of Indians along the whole coast of Hudson’s Bay [within the lowlands] would not exceed two thousand.”21 Not long after Graham wrote this, the smallpox epidemic of 1782–83 took a devastating toll among the Lowland Cree, reducing their numbers to about half, but by the 1820s the total population had returned to approximately the pre-epidemic level.22

Fish, waterfowl, and caribou were the only game animals accessible in large numbers to Subarctic hunters. Otherwise game was scarce in the northern boreal forests and the Hudson Bay Lowlands, causing Aboriginal peoples to live in relatively small groups during most of the year. Usually two extended families, often those of two brothers, would spend the long winter and most of the spring and fall together hunting and gathering.23 In the summer larger groups would congregate at preappointed places in fishing and goose hunting camps or at berry gathering sites. Such gatherings could include over two hundred people, while the number of persons in each hunting camp rarely exceeded thirty people.24 Referring to precontact and early contact times, Omushkego-Cree elder Louis Bird stated that according to his people’s oral traditions, the Winisk River system and its tributaries within the lowland region could sustain about twenty families.25

The climate of the Subarctic means that agriculture is practically impossible, while edible roots and berries are far from abundant for most of the year. Therefore hunting and fishing were the main means of securing food. Even then, large game was limited, and smaller animals such as fish and rabbits played an important part in the diet of Central Subarctic peoples.26 By the nineteenth century the increasing scarcity of large game favored individual hunting over communal hunting.27 Rabbits and other small game were often snared or trapped rather than actively pursued, since this conserved human energy. Later, the fur trade enhanced this emphasis on trapping, which in the Subarctic was concentrated on procuring beaver pelts, but also the furs of medium to small predatory animals such as river otters, martens, and fishers.

In the late seventeenth and early eighteenth century Aboriginal people in the Subarctic followed a relatively consistent pattern of seasonal migrations and activities throughout their territory in order to access various resources where and when they became available. For example, for the Omushkego-Cree, the annual cycle began in March.28 From their inland wintering sites they moved to the coast of Hudson Bay in spring to hunt ducks and geese and to escape mosquitoes, flies, and other parasitic insects, which were more numerous in the interior than near the sea. They knew that large mammals such as caribou also moved to the coast in spring and early summer to avoid these insects.29

By the end of March and the beginning of April large herds of caribou from the upland forest began to arrive in the coastal lowlands. These animals migrated along the coastline and then dispersed to their breeding grounds as far south as Cape Henrietta Maria and Akimiski Island in James Bay. In late summer they recongregated and took up the return journey. Once they reached the upland forests again, they dispersed into smaller herds for the winter. During these great migrations the caribou herds numbered in the tens of thousands, as several Hudson’s Bay Company employees observed during the eighteenth century. In anticipation of the spring migrations of caribou, Cree peoples set up hunting camps in late winter, close to the migration routes at places where the caribou could be hunted with relative ease.30

There were several ways to hunt caribou herds. According to Louis Bird, caribou were often driven into enclosures or narrow passageways between two converging lines of rock or snow piles. Hunters then waited at the narrow spot or at the enclosure to kill the animals with spears, bows and arrows, or later, with firearms.31 Just like Inuit and Alaskan Aboriginal peoples, the Omushkego-Cree, Northern Ojibwa, and Montagnais also hunted these animals in large “caribou drives.” Aboriginal peoples in the eastern and central Subarctic practiced this hunting method well into the first quarter of the nineteenth century.32

During the spring caribou migration, when the rivers were still frozen, fences or hedges were built with openings that contained snares to catch the animals’ heads. European fur traders copied this Aboriginal invention and in some instances built such hedges not far from a fur trading post.33 James Isham, a leading Hudson’s Bay Company officer active in the lowlands during the mid-1700s, described a caribou hedge made by Lowland Cree people:

Their snares are made of Deer, or other skins Cutt in strips, platting [plaiting?] several things [thongs?] togeather,—they also make snares of the Sinnew’s of beast after the same manner, they then make a hedge for one or two mile in Length. Leaving Vacant places,—they then fall trees and Sprig them as big as they can gett, setting one up an End at the side of the Vacant place, fastning the End of the snare to one of these trees, then setting the snare round they Slightly studdy [i.e., fasten or secure] the snare on Each side, the bottom of the snare being about 21/2 foot from the ground, Driving stakes under’ne that they may not creep under, they then Leave them when the Deer being pursued by the Natives other way’s they strive to go thro these Vacant places, by which they are Entangld and Striving to gett away the tree falls Downe, sometimes upon them and Kills them if not they frequently hawl these trees for some miles tell a growing tree or stump brings them up,—when the Indians going to the snares the next Day, trak’s them and Knock’s them on the head;—they Killing abundance after this manner, in the winter seasons,—the Uskemau’s Kills these Deer with Launces in the water, and upon the Land with bows and arrow’s.34

Caribou hedges required many people to build and maintain, as did the processing of the meat and hides after the hunt. Evidently many Cree people congregated at caribou hunting camps close to York Factory.35 When the rivers were open, hunters speared the caribou from boats while the animals were crossing the river.36 This method was also employed in the fall, when the animals crossed the rivers again in great herds on their way to their wintering grounds.

In spring, caribou were less desirable as a food source, commercial resource, or source of hides because the animals were still lean from the strains of winter, and their hides were infested with the larvae of the warble fly, which ate holes in the hides, making them extremely difficult to process and almost useless for most purposes.37

Nevertheless, the Swampy Cree killed many caribou in spring and fall because it was at this time that just a few short weeks offered the opportunity to gain an abundance of meat and raw materials. Even though the quality of the meat and hides was low, the rest of the year caribou were scarce and it was much harder for individual Cree to hunt these animals. Louis Bird stated about the caribou hunt:

In those times there were plenty of caribous. They were coming in and they [the Omushkego-Cree] know that they’re not gonna kill them all off. So that’s the time they do that. These are migrating caribous. They migrate from some place and they travel here, they will travel only in a certain month. So that’s when you kill as much as you can, but don’t kill them all off, because they’re plenty anyway. Sometimes you see maybe 25, maybe 15, you can do that. But when they’re declining, the caribous come and go, every 25 years or so, so there are plenty and then after that, not because you killed them off, because they move to other place.

It was done in such a way because people knew this is the only month that they can do that, March and April, May it’s a bit too late to do that. Only March and April that they can do that very easily. And you know that in May they’re not gonna be able to hunt big game animals because of slush. So they have to have extra, something that they can cache at their camp, during that time. That’s the only reason they do that. They have a reason when to kill many animals. Other than that you just don’t shoot them for anything. There’s no sport hunting. There’s no such thing.38

The most southerly location of caribou in the summer during the fur trade period was Akimiski Island. Cree hunters would move south in the summer to kill caribou there.39

Not all the Omushkego-Cree went downriver in the summer. Some stayed either at the headwaters, or about halfway downriver, wherever hunting was good. After the Hudson’s Bay Company established Fort Severn in 1685 near the mouth of the Severn River, Omushkego people went downriver to trade for European goods such as firearms, ammunition, metal tools, and weapons.40

Shortly after the spring migration of caribou, large numbers of geese, ducks, swans, and other migratory birds arrived in the Hudson Bay Lowlands in time for the spring breakup of rivers, lakes, coastal ponds, and sloughs. Migratory birds used these ponds and sloughs as a main feeding area. Several species of fish were also abundant in the Hudson Bay Lowlands during their spawning periods.41

In March the people left their winter camps to go goose hunting or “spring trapping.” This was finished in June. By the end of June they moved to the mouths of the rivers, or to a site along the river above the mouth, to get together in larger groups. At these gatherings they arranged and conducted marriages and held ceremonies and competitive sports events with singing, dancing, and drumming.42

While Canada geese and Brant geese remained in the coastal lowlands to breed, the onset of warmer weather in early summer drove most other geese to their breeding grounds north of the Hudson Bay Lowlands. Most Lowland Cree spent most of the summer in the coastal lowlands, hunting geese and individual caribou.

Fishing also continued in the summer but was generally not so productive in this season. Beluga whales were hunted in the estuaries of the larger rivers, where the animals were mostly speared with harpoons from canoes. To prevent upsets, several canoes would be lashed together tightly. Another method of whale hunting was to drive the animals into shallow water until they were beached on the tidal flats. Usually the Lowland Cree did not eat the flesh or the fat of white whales, but rather fed it to their dogs or sold it to European traders.43 The whale skin was a source of large amounts of rawhide, while the long sinews situated along both sides of the whales’ backbones yielded fibers for threads. Both materials could be used to make cordage.

Summer was also a season to gather various kinds of berries, such as gooseberries, cranberries, strawberries, raspberries, crowberries, or mawsberries, and plants for food and medicinal purposes. Aboriginal traders from other areas brought maple sugar north to the Hudson Bay Lowlands. Andrew Graham noted that such traders also brought “Indian corn,” which was probably wild rice rather than maize.44

By fall, people and large mammals began to move inland again, because by then the insects had sufficiently diminished. Once the insects were gone, people moved upriver again to find a wintering site on one of the tributaries of the Winisk or other river, somewhere between one hundred and two hundred miles inland. This was done to ensure good fishing. People knew that the fish would come downriver before January. Thus they set up fish traps, not only to catch fish for immediate use but also to dry them and later in the winter to freeze them in a cache. Fish weirs were mostly used in the fall. They served to catch most species except the larger fish, such as sturgeon, which were speared. Fish were also shot with arrows.45

Fish was the main staple food of the Swampy Cree throughout the winter, especially when larger game animals were scarce. Fish trapping therefore was one of the most important economic activities for the Lowland Cree. Aboriginal people in the Subarctic fell back on fishing whenever other resources failed. For instance, Andrew Graham observed in the 1740s that Ojibwa people resorted to fishing “when their gun and ammunition fails, or other food fails.”46

As far as meat was concerned, caribou were in prime physical condition in early fall after having fed throughout the summer on coastal grasses and other vegetation. The meat of mature male caribou was considered especially good eating before these animals exhausted themselves in the rutting season in late fall. However, hides were not in prime condition yet. This would only be the case in late fall and winter when all the injuries to the skin caused by parasitic insects had healed.47

The major caribou river crossings in the fall occurred some weeks before the fall goose hunt. Duck hunting preceded the goose hunt, because ducks arrived earlier than the geese from farther north. Therefore the Lowland Cree would set up camps near the regular crossing places in anticipation of the event. These lay from thirty to one hundred miles inland from the coast on the Severn and Hayes Rivers. Polar bears were also hunted in the fall for their fur and for their meat.48

In winter the Lowland Cree moved inland, away from the coast and into the forests, to hunt caribou, which were scarce near the coast at that time. During the cold season, woodland caribou were hunted mainly in the forested river valleys. The hides of these animals were in prime condition during the winter. Occasionally hunters also found caribou on Akimiski Island in winter.49 Winter was also the prime season to harvest fur-bearing animals, when their pelts were at their best, but these were trapped and hunted for food throughout the year as well. Women hunted, trapped, and claimed the pelts of immature beaver, muskrats, and other small mammals. They traded these at the posts for “beads, vermilion, bracelets and other trinkets.”50 Not only the male hunters but also the women, children, and elderly of several families participated in beaver hunting. While the meat obtained in these hunts was distributed among family members, the skins of the mature beavers belonged to the person who had first discovered the beaver house.51

Snowshoe hares were also an important food resource throughout the winter. Their skins were used to manufacture winter garments, especially the so-called rabbit-skin blankets, woven from twisted strips of their hides. Fishing was also important in winter, especially for provisioning people employed at and near the coastal posts.52 Several bird species were hunted for subsistence and later also for commercial purposes. For example, during the eighteenth century and even more so during the nineteenth century the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) sought to obtain swan skins and swan and goose quills to send to Europe for the manufacture of clothing and writing utensils.53

The willow ptarmigan (Lagopus lagopus), often referred to as “partridge” by HBC men, was an important food source. Several species of grouse, commonly referred to as “pheasants” by HBC personnel, were important as winter resources. Aboriginal people hunted waterfowl in large numbers even before the introduction of firearms, especially fowling pieces. They used nets as well as bows and special bird arrows for this purpose. Willow ptarmigan were most often caught in nets, but boys also shot them with bows and arrows; for instance, in 1769 Lowland-Cree boys near Severn House shot over one hundred ptarmigans with their arrows. About a century earlier fur trader and explorer Pierre Radisson claimed to have seen Aboriginal people kill three ducks with one arrow.54

These seasonal patterns and subsistence activities of the Omushkego-Cree were based on the exploitation of a wide variety of mostly scarce resources. The introduction of European tools and weapons, the growing involvement of the Cree in the fur trade and provisioning business, and the gradual decline of big game populations all reinforced the increasing importance of trapping and individual hunting and a gradual decline in group hunting that involved the participation and coordination of large groups of people who would afterward share the resources they had harvested.

Northern Plains

Until the establishment of reservations and reserves in the mid- to late nineteenth century, the Northern Plains saw extensive movements and displacements of Native peoples. By the mid-nineteenth century the Native inhabitants of the region included sedentary agricultural peoples such as the Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara living along the Missouri River and its tributaries in what is now central North and South Dakota. More mobile bison-hunting cultures living to the west, north, and south of them were the Dakota/Lakota, Assiniboine/Stoney, Cheyenne, Arapaho and Gros Ventre des Prairies, the Blackfoot, Plains Cree, Plains Ojibwa, Sarcee, Crow, and Eastern Shoshone.55

The terminology used to refer to different Aboriginal peoples in the Plains at different times is somewhat problematic because names applied to a particular group by outsiders have often entered into common usage in English, even though they do not represent the self-designation of the people referred to. Varied spellings and shifting political implications of these terms over time have further complicated the issue. For example, in Canada the term “Blackfoot” generally includes three subgroups, the Peigan, Blood, and Siksika. Their contemporary self-designations are Aputohsi-Pikuni or Piikani First Nation, Kainaiwa First Nation, and Siksika First Nation.56 However, because the establishment of the U.S.-Canadian border cut through their homelands, part of the Peigan ended up living in what came to be northern Montana. Thus, in the United States they are referred to as Piegan and sometimes as Blackfeet, which in American usage can also refer to all Blackfoot-speaking peoples.57 Their self-designation is “Amskapipikani (Southern Piegan).” Because some of the text documents used in this study relate to a time before the establishment of the international border, I chose to use the term “Pikani” to refer to the southernmost division of Blackfoot-speaking peoples at that time. In the same way, I use the term “Blackfoot” to include all Blackfoot-speaking peoples.58 One of the self-designations used by Blackfoot-speaking peoples is “Niitsitapi.” However, this has not entered common usage in English. Therefore, while it is ethically preferable to use the appropriate self-designations of Aboriginal peoples, to avoid confusion I decided to use those terms that are now common in English.

The Northern Plains is a vast geographical area in the heartland of the North American continent, bounded to the west by the Rocky Mountains and to the north by the North Saskatchewan River. It includes the southern parts of the Canadian provinces of Alberta and Saskatchewan, parts of southern Manitoba, and the states of North and South Dakota, northeastern Wyoming, and eastern Montana.59

Map 2. Approximate distribution of Aboriginal groups in the Northern Plains and surrounding area in the first half of the nineteenth century. Base map by Weldon Hiebert, Department of Geography, University of Winnipeg.

Most of the region’s rivers have their sources in the Rocky Mountains. The North and South Saskatchewan Rivers comprise the northernmost major river system of the Northern Plains, draining into Lake Winnipeg and ultimately into Hudson Bay. During the fur trade, this waterway was one of the most important travel routes between the northwestern Plains and the central and eastern boreal forest. Farther south, the Missouri-Mississippi River system provided another important access route to the Plains. Many of the rivers of the Plains are rather shallow and can dry up during the hottest summer months. The Plains are interrupted by a number of low to medium mountain ranges and hills, such as the Beaver Hills, south of the North Saskatchewan River; the Hand Hills, just north of the South Saskatchewan River; the Cypress Hills, just north of the Milk River; the Bear Paw Mountains; the Little Rocky Mountains between the Milk River and the Missouri River; and the Black Hills in western South Dakota.60

Sparse precipitation and extreme summer and winter temperatures characterize the continental climate of the Northern Plains. Due to the rain shadow effect of the Rocky Mountains, the average annual precipitation in the Plains from southern Alberta as far east as southern Manitoba can be as low as 250 millimeters. In large areas of the Plains the amount of available moisture, either for growing crops on the Upper Missouri or for grazing in the more western portions, is often marginal.61 Strong and almost ceaseless winds are another crucial factor in shaping the climate of the Northern Plains. They subject the region to some of the most sudden weather changes. The Chinook winds, for instance, can bring midwinter temperatures to well above freezing within only a few hours, while blizzards coming down from the north or northeast can quickly push temperatures well below freezing.62

From the last ice age to the last quarter of the nineteenth century, the Great Plains was populated by vast herds of bison, antelope, deer, and elk, feeding on a wide variety of different prairie grasses. The hunting of the bison herds to near extinction during the late nineteenth century, combined with attempts at turning the arid and semiarid Plains into farmland, which led to the demise of native grasses, have changed this environment beyond recognition.

Due to their height, the small mountain ranges east of the Rockies receive more precipitation than the surrounding plains. These higher elevations are characterized by cooler summer temperatures, which translate into less evaporation. They therefore sustain a more robust and rich plant growth than the surrounding mostly treeless plains. It was in these elevated regions that most of the forests of Northern Plains were located. These mountains and hills supported among others, lodgepole pine (Pinus contorta), jack pine (Pinus divaricata), white spruce (Picea glauca), and Douglas fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii). Deciduous trees such as cottonwood (Populus balsamifera spp. trichocarpa) and, farther east, elm (Ulmus procera), white ash (Fraxinus americana), and green ash ( Fraxinus pennsylvanica) and conifers such as juniper (Juniperus spp.) grew in the sheltered river valleys.63 The plains around these mountains supported a wide variety of grasses, which were the mainstay of the region’s population of large ungulates. A greater availability of forage in the foothills and river valleys meant that plant-eating animals were more abundant and more consistently found in these regions than on the open plains.

Aboriginal people of the region gathered a wide variety of plants for food or medicinal purposes. They included prairie turnips (Psoralea esculenta), the groundnut (Apios americana), and the hog peanut (Amphicarpaea bracteata).64 Other food plants included the Jerusalem artichoke (Helianthus tuberosus) and the purple poppy mallow (Callirhoe involucrate). Several types of berries were also collected and consumed fresh or dried. These included wild plums (Prunus spp.), chokecherries (P. virginia), silver buffalo berries (Shepherdia argentea), Saskatoon berries or Juneberries (Amelanchier alnifolia), and hackberries (Celtis occidentalis).65

Due to its sparse precipitation, extreme temperatures, short growing seasons, and high winds, most of the Northern Plains was unsuitable for Indigenous agriculture. While on the eastern fringe of the region an Indigenous way of life based on a combination of agriculture and hunting had emerged, the inhabitants of the High Plains relied on gathering and on hunting big game animals. In contrast to other hunter-gatherer cultures that obtained the main portion of their food through gathering, the bison-hunting cultures of the Northern Plains and the peoples of the Subarctic relied more on harvesting animals, because the High Plains and especially the Subarctic environment contained very few edible plants.66

The major species of large mammals in the Plains were the American bison (Bison bison) and the pronghorn antelope (Antilocapra americana). Mountain sheep (Ovis canadensis) were found in the foothills of the mountains and in other rough areas, such as the badlands of modern North and South Dakota and Alberta. Brush areas and the wooded river valleys provided a habitat for woodland and forest-edge species, such as mule deer (Odocoileus hemonius), elk (Cervus elaphus), and occasionally moose (Alces alces). All these were hunted for food, hides, and other raw materials, such as sinew, antlers, or bones. However, only the bison and pronghorn antelope occurred in large herds and were hunted in large “drives.” Mountain sheep were occasionally hunted in smaller drives as well. Elk, deer, and moose occurred in smaller groups or even as individual animals. They were mostly pursued by individuals or by very small groups of hunters.

Smaller mammals included the beaver (Castor canadensis), the raccoon (Procyon lotor), the muskrat (Ondatra zibethicus), the desert cottontail (Sylvilagus audubonii), and the jackrabbit (Lepus spp.).67 Predatory mammals of the Northern Plains included the grizzly bear (Ursus horribilis), black bear (Ursus americanus), mountain lion (Felis concolor), wolf (Canis lupus), coyote (Canis latrans), lynx (Lynx canadensis), bobcat (Lynx rufus), wolverine (Gulo gulo), river otter (Lutra canadensis), marten (Martes americana), fisher (Martes pennanti), mink (Mustela vision), and different species of fox, such as the kit fox (Vulpes macrotis) or the North American red fox (Vulpes fulva).68

Bird species from eastern and western North America shared habitats in the Northern Plains. For instance, the wild turkey (Meleagris gallopavo), a major source for some of the best-quality feathers for arrow fletching, ranged as far west as there were trees to roost in and grasshoppers to feed on. Other birds hunted for food and feathers included the sharp-tailed grouse (Tympanuchus phasianellus), greater prairie chicken (T. cupido), and the sage grouse (Centrocercus urophasianus).69 Resident waterfowl and large numbers of migrating ducks, geese, and swans congregated at waterholes and upland ponds. A wide variety of smaller birds were present, and there were also various species of eagles, hawks, buzzards, owls, and other raptors.70 These supplied materials for decorative, ceremonial, and ritual items, but also for weapons accessories, such as arrow fletchings.

Indigenous Peoples’ Subsistence Patterns and Hunting Strategies

In the Northern Plains the adoption of horse technology in protocontact times and just after contact brought about gradual but significant changes in Aboriginal hunting methods and subsistence strategies. Documents created by outside observers in early contact times provide information on subsistence patterns, social organization, and material culture, and they offer some insights into Aboriginal peoples’ lifeways in precontact times. Documentary evidence on the locations of specific Indigenous peoples is largely absent until the later eighteenth century. However, archaeological information provides some clues about which Aboriginal groups inhabited which parts of the Northern Plains during the times immediately before contact. Scholars of the Great Plains have long tried to link Aboriginal groups known from historical documents to archaeological evidence stretching back far beyond the times of first contact between Aboriginal peoples and Europeans. Such efforts have produced hotly contested debates, because it is often difficult to link archaeological remains with more recent cultural communities.

There is, however, consensus that two archaeological cultures, Old Women’s and One Gun, dominated the northwestern Plains at the time that European horses reached the area. The distribution of archaeological materials from the Old Women’s phase at the end of the pedestrian era matches the distribution of the Blackfoot bands when Europeans first encountered them. This suggests that their ancestors probably left most of the artefacts now classified as Old Women’s ware.71

Furthermore, when Europeans first encountered Blackfoot peoples, their lifeways bore a greater resemblance to those of other Plains peoples than to Woodland or Subarctic cultures.72 This evidence, combined with oral history, strongly suggests that the Blackfoot have ancient roots in the northwestern Plains. While groups ancestral to some of the Plains Cree were resident in the Saskatchewan River basin in the 1600s, other Algonquian speakers, such as the Arapaho and Cheyenne, migrated to the Plains more recently.73

Documentary and archaeological evidence also links the carriers of the archaeological culture known as “One Gun” to the Hidatsa, proto-Crow, and Crow peoples of the Northern Plains between 1675 and 1750. These groups, as well as the Mandan, had strong ties to and probably emerged from the Middle Missouri archaeological tradition.74

Subsistence Patterns

Some Aboriginal groups in the eastern area of the Northern Plains, as far west as the Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara, practiced a mixture of hunting on the open plains and agriculture in the fertile river bottom lands of the Missouri and its tributaries, living in permanent earth-lodge villages. However, most other Indigenous peoples of the Northern Plains lived a more mobile existence and largely depended on the bison as the major game animal. In order to understand Indigenous peoples’ subsistence patterns and yearly cycle of activities, those of the bison need to be understood. Scholarly opinion on bison behavior during historic times is divided. While some scholars see the bison’s migrating behavior as totally erratic and unpredictable, others, such as Theodore Binnema and Trevor Richard Peck, argue that bison migrated within narrowly defined regional boundaries, following an established routine and utilizing different plant foods in different locations at different times of the year.75 According to these views of fairly predictable and localized patterns of migration, bison moved from parkland and riverine habitats in spring to various prairie and plains environments through the summer, following the growing seasons of different types of grasses.76 For the winter they returned to the parklands, the sheltered river valleys, and the foothills of the mountains to begin this cycle anew in spring.77 In spring, bison herds were still small and widely dispersed. Hunters found it difficult to depend on these animals then, so they gathered bitterroot, prairie turnips, and camas in the spring and early summer. War expeditions were rare in spring, because food could be scarce and Aboriginal bands were busy preparing for the endeavors and activities of summer.

By July, the warmest month in the Plains, food had become sufficient for bison herds to slowly begin to congregate. The bison rut approached in early July and peaked in early August, when mature bulls, who formed separate herds for most of the year, came together with the cowherds, establishing few but very large herds. By late summer, especially in dry years, many water sources in the Northern Plains had disappeared. When the weather cooled in August, the growth of prairie grasses slowed. Then the bison gravitated again to the moister prairie and riverine habitats, because water and forage were more plentiful there, and because the open plains were relatively inhospitable to them during the winter.78

During the equestrian era, Plains peoples’ largest annual gatherings of the year took place in June or early July. At this time families and individuals strengthened their social and political bonds and renewed their relationships during the annual Sun Dance. This was also the time for communal bison hunts to provide summer hides and food for the annual summer gatherings.79 Most war and raiding expeditions also took place in summer. Even though large numbers of horses required frequent short-range location changes in order to access fresh pasture, large encampments were easier to maintain during summer because of the abundance of provisions that could be obtained from the gathering bison herds and the prolific Saskatoon berries. Women gathered berries to be eaten fresh or dried and stored in bags for later use. Men could travel considerable distances on horseback to find bison herds and transport meat.80

In early winter most of the bison had migrated toward sheltered river valleys or the foothills of the mountains to avoid the brutal winter winds and food shortages on the open plains. Not only bison but also other large mammals such as elk tended to congregate in the river valleys during winter for the shelter, water, and food the valleys provided. People took advantage of this migration pattern to be closer to the animals they hunted and also to find fuel and shelter in the forested river valleys. In late fall and early winter the bison were still in good condition and had already developed a dense winter coat, which was desired to make robes and other items of winter clothing. Therefore this was the time for the second major communal bison-hunting efforts of the year.81 Before the use of horses in bison hunting, fall and early winter had been the principal season for large communal gatherings, because this was also the principal time that pedestrian bison hunters could use bison jumps and pounds. However, the increasing utilization of horses enabled selective hunting of two- to five-year-old female bison, which Native hunters preferred for their better meat and smaller hides, which were easier to process. The use of horses also caused a gradual shift of the main hunting season from fall-winter to summer, which consequently shifted the main season for communal gatherings into summer as well.82

Early Communal Bison-Hunting Methods

Before the adoption of the horse, the preferred communal bison-hunting method consisted of driving a herd of bison over a cliff or into an enclosure where the animals were either fatally injured from the fall or could be killed with spears or bows and arrows at close range. To guide the bison toward the kill, Native people took advantage of the natural features of the landscape as much as possible, placing two lines of obstacles, over a mile in length, in a V shape, converging at the entrance to the pound or at the lip of a cliff. Prominent bison jumping sites were in use by various Aboriginal groups for thousands of years. One of the most well known is the Head-Smashed-In Buffalo Jump in southwestern Alberta. Beginning about 5,500 years ago, various Indigenous peoples killed bison at this site. Evidence of material culture from the Old Women’s cultural complex, believed to represent the ancestors of the Blackfoot, spans the time from ca. AD 850 to the later nineteenth century at the site.83 During the nineteenth century, Blackfoot-speaking peoples lived in the area of the Head-Smashed-In Buffalo Jump and continued to use such sites as late as 1872.84

The use of bison pounds extended far into Blackfoot peoples’ past and was deeply rooted in their mythology. Robert Nathaniel Wilson, who served with the Northwest Mounted Police in Alberta in the early 1880s and who later became an Indian agent among the Peigan and Blood, recorded the following account from Blackfoot people about the origins of this hunting method:

People were at first the progeny of Buffalos, which were in the habit of eating people and caught them in a pound. Napi [the Blackfoot culture hero, with attributes of creator and trickster] came across the people in the mountains where they were hiding from the Buffalo and told them that state of affairs was not right. “Buffalo,” said he, “are intended for people to eat and I will fix these things as they should be.” He showed them how to make the bow and flint-headed arrow.85

In the winter of 1792–93, Peter Fidler, a trader and surveyor, and John Ward, an Orkney laborer, both working for the Hudson’s Bay Company, accompanied a large band of Pikani-Blackfoot under the leadership of Sakatow on a journey from the HBC’s Buckingham House on the North Saskatchewan River to their wintering grounds near the Rocky Mountains in the Bow River area.86 During this trip Peter Fidler recorded some Pikani hunting methods. He visited several buffalo jump sites and pounds and described how they were used. For example, on one occasion hunters drove twenty-nine buffalo over a cliff. Three of these animals survived with broken legs and were killed with arrows.87 When a hunt failed because the bison broke through the funnel barriers leading to the cliff, the men killed several by galloping after them on horseback and shooting them with arrows.88

Pronghorn antelope and mountain sheep were also hunted using surrounds or cliff drives. During the nineteenth century the Cheyenne were most noted for their large antelope surrounds, and this hunting method remained in use into the 1870s.89 Peter Fidler also noted that the Pikani constructed pounds to hunt mountain sheep in great numbers.90

Fig. 3. Plains Cree bison pound showing converging lines of hunters and obstacles, guiding the animals into the pound. Colored wood engraving after an unknown original made on the Henry Hind expedition of 1857–58.

Fig. 4. Romanticized view of a buffalo jump as envisioned by the American painter Alfred Jacob Miller, who traveled through the Northern Plains in 1837. Image courtesy of the Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, Maryland, accession number 37.1940.190. Title: Hunting Buffalo, by Alfred Jacob Miller (1837).

Aboriginal people of the Plains utilized bison not only as a major food supply but also as a source of raw materials. After the hunt the bison had to be skinned and butchered, the meat had to be cut up and dried to preserve it for future use, and some of the internal organs were cleaned and made into containers. Peter Fidler observed that the Pikani preferred deerskins for making brain-tanned leather to manufacture “Jackets—Stockings, shoes etc., which is much more durable & neat than the buffalo leather.”91 The heavier bison hides were made into robes and other winter garments. With the hair removed they were made into tent covers and liners. Aboriginal people used soft-tanned bison hides or bison rawhide to make a wide variety of containers, such as saddlebags, hunting pouches, quivers, bow cases, and parfleches. Bison hides were also made into ropes. Hide scrapings left from the cleaning and tanning process were boiled into hide glue. Fleshers, arrow-making tools, and weapons were made from bison bones. The tendons and back sinew yielded fibers necessary to make thread for sewing and embroidery, for wrapping arrow points onto arrow shafts, or for fixing the fletchings to arrow shafts. Sinew was also used to make bow backings, bowstrings, and cordage in general, such as sewing thread or nooses for snares.

As a horse culture developed in the Plains, although bison were still driven into pounds or over cliffs, from the mid- to late eighteenth century they were also increasingly hunted on horseback with bows and arrows.92 The tendency of bison to herd together as they stampeded facilitated this type of the hunt. Because bison had greater endurance than even the fleetest horses, the chase lasted only as long as the horses could keep up.93

At least in equestrian times, the relatively constant abundance of bison in the Northern Plains as a food source enabled Aboriginal people to sustain themselves in relatively large groups.94 Most Plains groups would congregate in even larger numbers during the summer to hold annual ceremonies and hunt bison communally.

In contrast, in the Subarctic, especially in the Hudson Bay Lowlands, such large gatherings could be maintained only for very brief periods because so many people living in any one place for an extended period would soon exhaust food supplies. The decline of the caribou and moose populations in the Hudson Bay Lowlands during the second half of the eighteenth and the early nineteenth century reinforced this development. Large gatherings of Subarctic people took place mostly during the fishing season, because fish provided a more reliable food source.

Different environmental constraints in the Plains and the Subarctic led to different types of social organization among the Aboriginal people who inhabited these two regions. People adapted to the Subarctic environment by living in small family groups throughout most of the year. Such restrictions were not as necessary in the Northern Plains where the large herds of herbivores provided a more consistent food source. This made it possible for larger groups of people to stay together longer. During the equestrian era the trend toward larger bands and villages in the Plains persisted, even though camps had to be moved frequently for short distances to find fresh pasture for the horses.