Bows of the Northern Plains and Subarctic

This study is concerned with a comparison of Aboriginal peoples’ use of Indigenous distance weapons and European firearms. Because firearms were mostly used in big game hunting and combat, this examination of Aboriginal archery also primarily focuses on these activities, even though bows had other uses, such as hunting rodents or birds. Other distance weapons, such as lances, spears, spear throwers, and darts, were important long before Europeans arrived, but they lie beyond the scope of this study. This chapter describes major bow types of the Northern Plains and Central Subarctic. Different types of arrows are discussed in later chapters.

The details of Aboriginal archery present numerous interpretive problems. Scholars unfamiliar with the technology have sometimes misinterpreted the archery gear they examined, and modern “inventions of tradition” have obscured past practices. The asymmetrical bow of the Northern Plains and the so-called Penobscot double bow, as we shall see, have both been subjected to these problems. Careful comparisons of Aboriginal traditions with accounts by non-Aboriginal outsiders, study of surviving artefacts, and experience gained through the manufacture and testing of reproductions of Aboriginal archery gear have led me to a great appreciation of the capabilities of these weapons and the ingenuity of Aboriginal technology.

The exact time of the introduction or emergence of archery technology in North America is still debated by archaeologists. Because organic materials such as wood, hide, and plant and animal fibers do not preserve as well as stone and ceramics, the study of ancient weapons in North America relies mainly on the comparison of lithic tools and projectile points. It is beyond the scope of this study to provide a detailed analysis of precontact lithic projectile point types; rather, it focuses on the period after European goods became available to Aboriginal peoples in the Subarctic and Northern Plains.

In interpreting changes in lithic projectile point size and type, Brian O. K. Reeves suggests that archery replaced atlatl (spear thrower and dart) technology in the Northern Plains between AD 450 and AD 750, because arrows supposedly required much smaller projectile points than the darts used with the atlatl.1 Interpreting the relatively small side-notched lithic projectile points of the Avonlea complex as arrowheads, archaeologist John Blitz suggests an even earlier date of AD 200 for the introduction of the bow and arrow to the Northern Plains.2 Based on the appearance of small, arrowhead-sized projectile points of the Pelican Lake archaeological phase, archaeologist Philip Duke stated that bow and arrow technology may have been present in the Northern Plains as early as 1500 BC.3

Some of the oldest clearly identifiable archery artefacts of North America come from the Mummy Cave site in Wyoming and have been dated to approximately AD 730. These artefacts include shaft fragments identifiable as arrow parts because of their notched ends, which would accept a bowstring, but not the hooked protrusion of an atlatl, or spear thrower.4 Regardless of the course of its emergence, archery technology was well developed by the time European trade goods and horses reached Aboriginal people in North America.

Some Bow Physics and Archery Terms

Before discussing specific bow types, some technical terms and some of the physics of archery need to be discussed. A bow is essentially a two-armed spring with a string connecting its ends. When an arrow is put on the string and the bow is drawn, it stores energy, which is transferred to the arrow upon release of the bowstring. However, when the bow is drawn, tensile stress builds up along the back, or outside curve, while compressive strain develops on the belly, or inside curve. Regardless of design or materials used, every bow has to accommodate these forces in order to successfully propel an arrow and to avoid breaking in the process.

On most North American Indigenous bows, the string needs to be loosened on one end when the weapon is not in use in order to preserve the bow’s elasticity. Only when the bow is about to be used is it bent and the string put on. This process is referred to as “stringing.” The side of the bow that in shooting is facing the target is referred to as the “back,” the side facing the archer is referred to as the “belly.” A bow can be envisioned as a person, facing and bending toward the archer, just as a person bends more readily toward the belly than the back.

A “reflex” denotes a bow with a permanent curve toward the target or toward its back when it is unstrung. This enhances its draw weight and possibly the distance it can cast an arrow.5 A bow that curves toward the belly when unstrung is said to “follow the string.” Such a permanent curve toward the belly causes the bow to store less energy when it is drawn, which is usually detrimental to the cast of the bow and lowers its draw weight, but it also renders the bow safer to use, because it is strained less when strung and drawn. A bow with its outermost parts (tips) bending toward the target when the bow is relaxed, is recurved. The recurves help to store more energy in each bow limb, but recurves also increase the stress the limbs of the bow have to endure. Apparently, true recurves were rare in the Plains-Plateau region but were fairly common in the Great Lakes area and in parts of California and the West Coast.

Bow Types of the Northern Plains and Adjacent Regions

Aboriginal bows can be classified using several criteria, for example, their length, shape in side view or front view, or orientation of the grain.6 However, archers tended to fit their equipment to their individual needs and their preferred method of shooting. Thus, too rigid a classification can obscure important adaptive techniques and strategies.

Fig. 5. Parts of a bow, showing tension and compression strain. Drawing by Margaret Anne Lindsay.

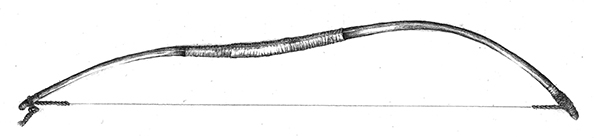

Fig. 6. Unstrung Plains Cree self bow, collected by Major George Seton in the Red River Settlement, now at the British Museum. An inscription on the bow reads: “Cree Indian Bow—Fort Garry Ruperts Land 1858.” Note the permanent bend toward the string, or “string follow.” Image copyright Trustees of the British Museum, Coll. No. AN308525001-Am1982,28.15.a.

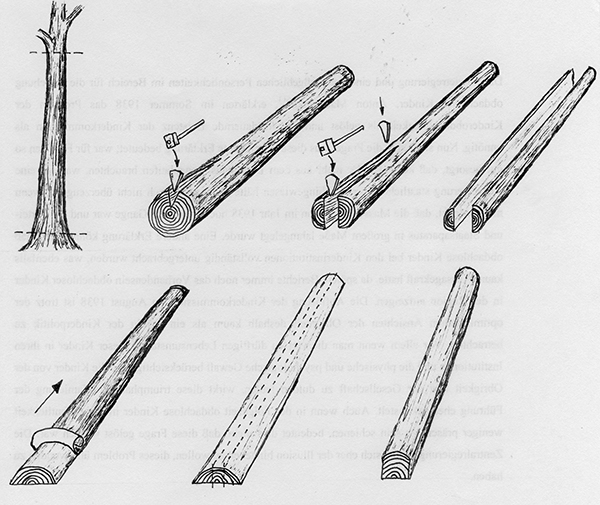

Fig. 7. Basic construction steps from tree to bow stave, from upper left to lower right: (1) felling of suitable tree; (2) initiating split parallel to the long axis of the tree trunk; (3) widening and extending split with multiple wedges; (4) completed split; (5) removal of bark; (6) positioning and outlining dimensions of bow stave within the larger piece of wood to avoid knots and other difficult spots; and (7) removing excess material from the sides of the bow stave. Note how one uncut growth ring from the outside of the tree forms the back of the bow. Drawings by Roland Bohr.

Fig. 8. Lakota self bow with growth rings cut through on the back, resulting in a catastrophic break from the back when the bow was drawn or bent. Note the sequence of cut growth rings appearing as a chevron pattern to the left of the break (A). The break occurred exactly at the intersection of two cut growth rings (B). Courtesy of the Northwest Museum of Art and Culture, Spokane, Washington, Clarence H. Colby-Collection (Colby 69.33). Photographs by Roland Bohr.

Fig. 9. The same Lakota self bow as in Figure 8, viewed from the back. The break and cut growth rings are visible near the middle of the right limb, where most of the bending stress would occur when the bow is drawn. This bow is 113.6 cm long. Photograph by Roland Bohr.

![]()

Fig. 10. Omaha self bow with an intact, uncut growth ring as the back. Note the smooth texture on the back of the bow and the absence of chevron patterns, which would indicate cut growth rings. Measured along the back, this bow is 126.8 cm long. This bow was made before 1898 for a collection for the Ethnologisches Museum, Berlin, compiled by Francis LaFlesche from his own Omaha community. Courtesy of Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Ethnologisches Museum (Cat. No. IV B 2189). Photograph by Roland Bohr.

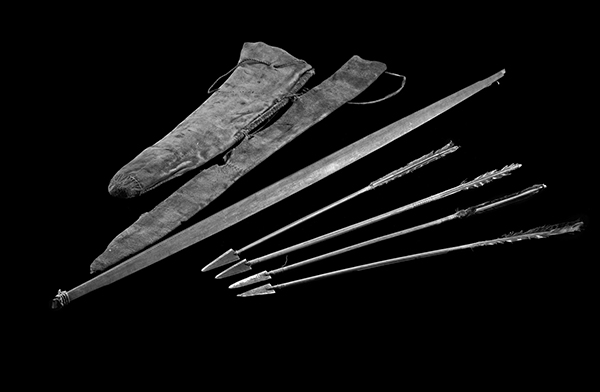

Fig. 11. Osage bow with arrows and cases, collected by Duke Paul von Württemberg in 1824. The bow is made from Osage orange wood, with an intact growth ring as the back. Note the absence of chevron grain patterns, indicative of cut growth rings. This bow is 120 centimeters long and is now at the British Museum. Image copyright Trustees of the British Museum, Coll. No. AN166096001-Am.5206.a.

Fig. 12. Blackfoot bows, arrows, and quiver/bow case at the American Museum of Natural History. The sinew-backed bow on the left is shown unstrung, with the string on the “wrong” side (i.e., toward the back). This bow is highly reflexed. It was collected in 1870, together with the arrows and the quiver/bow case of otter fur. The strung bow on the right is a self bow of more recent manufacture than the first bow, according to Wissler. It resembles the Plains Cree (Red River) self bow shown in Figure 6.

A more helpful approach, based on documentary evidence and surviving artefacts, is to classify Aboriginal bows of the Northern Plains (and the adjacent Parklands and Plateau regions) into three main categories according to the materials used in their construction: so-called self bows, sinew-backed wooden bows, and sinew-backed horn or antler bows.7 Of the 113 bows that I examined, seventy-four were self bows, thirty-two were sinew-backed wooden bows, and seven were horn or antler bows.

Self bows were made from a single piece of wood, often taken from a sapling or small tree. In order to accommodate the tensile stress along the back of such a bow, the bow stave was often laid out in such a way that a continuous and uncut growth ring formed the back of the bow. Sometimes, only the bark was removed and the outermost growth ring of the tree became the back of the bow, if it was considered thick enough to bear the tension strain. In regard to self bows used by Native people in the Plateau area immediately to the west of the Plains, North West Company fur trader Alexander Henry the Younger observed in 1811: “The plain wooden bow is a slip of Cedar or Willow or Ash wood, the outside is left untouched further than taking off the Bark.”8 This indicates that an uncut growth ring formed the back of the bow. Aboriginal elders Louis Bird and Clifford Crane Bear, in explaining the usual technique for the manufacture of self bows among Swampy Cree and Blackfoot peoples, respectively, emphasized the importance of maintaining an uncut, intact growth ring as the back of the bow.9 Contemporary traditional bow makers continue to stress this construction feature as important for the manufacture of successful and durable self bows.10

The growth rings of a tree consist of layers of long wood fibers running parallel to its vertical axis. If these fibers remain uncut within one entire growth ring, they stand a much better chance of sustaining tensile stress. If a tree’s sapwood is not strong enough to bear the tension stress, the bow maker can expose the heartwood down to a growth ring that is thick enough to form the back of the bow.11 In this case, all the wood above the chosen growth ring is removed, while taking care not to cut into the underlying growth ring in any way. The backs of such bows show a smooth surface without any grain pattern.

If a growth ring has been cut on the back of a bow, a grain pattern of chevrons or ovals is visible on the back. If such a bow is drawn, the damaged layers of growth rings tend to peel apart under the tension strain, causing the bow to fracture, especially after the wood has seasoned. Bows made by Aboriginal people in the very late nineteenth or twentieth century often show cut growth rings on their backs and fractures at the intersections of the rings, but surviving Plains self bows from earlier in the nineteenth century often show smooth backs with intact growth rings.12

Clifford Crane Bear described how he made bows from the wooden handles of hockey sticks when he was a child in the 1950s. Because of the way the wood had been milled, without concern for intact growth rings, they did not hold up well under the tension strain when the bow was drawn, and soon broke. Sometimes Aboriginal people did make successful bows from milled lumber, such as boards and wagon parts. However, the cutting angles of such machined pieces of wood made different bow-making techniques necessary.13

Another useful technique in the manufacture of self bows is referred to as “decrowning.” For example, if the curvature on the back of the bow, seen in cross section, is too great and would thus concentrate all the tension strain along a narrow strip or ridge at the very top of the arch along the back of the bow, the growth rings can be cut in an attempt to create a level and almost perfectly flat surface on the back.14 In such a bow, the dividing layers between growth rings will show as parallel dark lines, running along the long axis of the bow and not as chevrons or triangles. None of the Aboriginal bows I examined showed this design feature.

A variant of this technique, especially useful when making bows from small-diameter branches or saplings, is to reverse the bow stave and use the inside of the split branch as the back of the bow. The outside of the tree thus forms the belly, with a semicircular cross section, concentrating the compression strain along the highest point of the arch on the belly. However, among the seventy-two self bows I examined, only one had this construction feature.15

In 1787 the fur trader and explorer David Thompson spent a winter among the Pikani in what is now southern Alberta. His host and informant was Saukamappee, a Cree by birth, who had married into the Pikani community as a young man and who may have been in his eighties when David Thompson stayed with him. Saukamappee described the relatively long bows that he, his father, and other Parkland-Cree warriors had used in the early 1700s as made of larch and reaching up to the chin in length. In Canada, larch is also called tamarack (Larix laricina). Louis Bird pointed out that tamarack was a common bow wood used by the Cree and other Aboriginal people in the northern boreal forests.16 Saukamappee’s account does not mention any backing on these bows; therefore these weapons were likely self bows, made from a single piece of wood. In contrast, he described the bows used by their “Snake Indian” (possibly Shoshone) adversaries as follows: “their Bows were not so long as ours, but of better wood, and the back covered with the sinews of the Bisons which made them very elastic, and their arrows went a long way and whizzed about us as balls do from guns.”17 This is clearly a description of the second category of bows to be discussed here, the short sinew-backed wooden bows that were so common in the Plains and Plateau regions until the last quarter of the nineteenth century.

In 1811 Alexander Henry the Younger observed about sinew-backed bows made by Native people in the eastern Plateau area: “The Bows used by the natives to the Westward of the Mountains are very neatly made and of three kinds: the Horn bow, the Red Cedar, and the plain Wooden bow. . . . The red Cedar bow is made out of a slip of that wood and over laid with sinew and glue in the same manner as the Horn bow. The inside is well polished. They are near four feet long, and will throw an arrow to a great distance.”18

The German naturalist Prince Maximilian of Wied, who traveled in the Upper Missouri region in 1833–34, observed:

The weapons of the Mandan and Manitaries [Hidatsa] are, first, the bow and arrow. The bows are made of elm or ash, there being no other suitable kinds of wood in their country. In form and size they resemble those of the other nations; the string is made of the sinews of animals twisted. They are frequently ornamented. A piece of red cloth, four or five inches long, is wound round each end of the bow, and adorned with glass beads, dyed porcupine quills, and strips of white ermine. A tuft of horsehair, dyed yellow, is usually fastened to one end of the bow.19

As accounts by Saukamappee (David Thompson), Alexander Henry, and Prince Maximilian indicate, compared to eastern North American, Subarctic, or Parkland bows, those from the Northern Plains and the Rocky Mountains were rather short, doubtless because of the scarcity of bow wood of suitable length, straightness, and freedom of knots. In the windswept Northern Plains the few straight and tall hardwood trees, such as ash, occurred almost exclusively in the sheltered river valleys. Owing to the construction of large reservoirs along the Missouri and other major rivers of the Plains, this source of bow wood has largely disappeared. For bows I manufactured as part of an anthropological study at the University of North Dakota in 1995–96, I used ash wood taken from the shelterbelt of a field. The search for this wood was conducted not only on foot but also by car, driving cross-country, and it took many hours to find a young ash tree of sufficient quality and straightness in a densely planted shelterbelt.20

Even before the construction of dams and reservoirs, serviceable bow wood may have been hard to find in the Northern Plains. In regard to the regional scarcity of wood, Hudson’s Bay Company fur trader Peter Fidler noted in 1792: “Very little wood here of any kind & to the South extensive plains, which continues several Hundreds of Miles nearly in that direction without a single Tree, to be seen. This I have partly proved to be true in my Journey to the Rocky Mountains in the following winter, & from the united testimonies of every Indian I have spoke to on the subject.”21

Because good bow wood was rare, bowyers had to make do with shorter, more knotty pieces of wood taken from shrubs such as chokecherry (Prunus virginia) or Saskatoon berry (Amelanchuer alnifolia, also known as Juneberry, sarvisberry, or serviceberry). However, bows made from such pieces of wood distributed tensile stress much less evenly than longer bows made from straighter wood.

To overcome the problems of working with inferior wood, Plains Aboriginal bow makers glued one or more layers of animal sinew to the back of their bows, using hide glue or fish glue.22 When the combined matrix of glue and sinew dried, it clung tightly to the wood and absorbed the tension strain, thus protecting the bow from breaking. This allowed bow makers to use much shorter and more flawed pieces of wood than would have been needed for longer self-bows.

According to George Bird Grinnell, who obtained information from Piegan people in the late nineteenth century, ash was their preferred wood for making bows. They used to collect it from an area close to the Sand Hills of what is now southeastern Alberta. When ash was not available, chokecherry was a second choice, but it was said to lack strength and elasticity.23 Confinement on reserves and reservations from the last decades of the nineteenth century onward may have prevented access to ash wood from the Sand Hills, and locally available woods such as chokecherry were primarily used for the manufacture of bows from then on. John Ewers, who collected information from Blackfoot peoples much later than Grinnell, learned that chokecherry was the preferred bow wood among Blackfoot-speaking peoples.24 My own efforts at making Plains bows from this wood have largely turned out unsuccessful, likely because I used wood that had been seasoned for several years and perhaps was dried out too much. When I mentioned this to Kainai elder Mike Bruised Head, he acknowledged that chokecherry was preferred among his people, but that all major woodworking needed to be done while the wood was still “green,” or unseasoned. After this, the bow stave was covered in grease or oil and left to season. Only the “tillering,” the fine-tuning of the bend of the bow, was done after the wood had seasoned.25

Aboriginal people in the Northern Plains occasionally obtained wood for bow making through trade from regions outside the Northern Plains. The Crow Indian Two Leggings recalled that when he was a young man in the 1860s, he traded several hickory staves from the Gros Ventre to make bows.26 Based on his observations while traveling the Missouri River region in Montana in 1833–34, Prince Maximilian believed that the country of the Blackfeet did not produce any wood suitable for bow making and stated that therefore they traded “bow wood,” or “yellow wood (Maclura aurantiaca) from the river Arkansas.”27 The yellow color suggests that it may have been Osage orange (Maclura pomifera), a wood that Southern Plains people such as the Kiowa, Comanche, and Osage regarded highly for bow making. A year prior to Maximilian’s visit in the area, the American painter and explorer George Catlin met with Blackfoot-speaking peoples in the Upper Missouri region and claimed to have observed their use of short sinew-backed wooden bows, made from ash and Osage orange.28 Indeed, the bowyer Jim Hamm mentioned two surviving bows made of Osage orange, collected from the Blackfoot.29 If such trade occurred on a regular basis, it is likely that instead of rough and fairly large pieces of wood, nearly finished bows or even completed weapons were traded.30 Alexander Henry the Younger stated that “these people [Flathead, Kutenai, Pend-d’Oreille, Nez Perce and other Plateau peoples] make by far the handsomest bows I have seen in this Country and they are always preferred by other Indians. I have seen a Peagan [Piegan/Peigan] pay a Gun or a horse for one of those sinew bows.”

Aboriginal people may also have obtained finished bows from outside their homelands as gifts or as war trophies. Especially among the Blackfoot, the capture of an enemy’s bow or gun in battle counted as a high war honor and was viewed as a very prestigious accomplishment.31 For example, in 1833 at Fort McKenzie in present-day Montana, Prince Maximilian met with the Piegan White Buffalo, “who often visited us, [and] one day brought a very beautifully ornamented bow, taken from the Flatheads, which, however, he could by no means be prevailed upon to sell. On making a higher offer, he answered, ‘I am very fond of this bow.’”32 In a similar example, a steer hide painted in 1892 with the war exploits of three Piegan men, Shortie White Grass, Sharp, and Wolf Tail, shows White Grass’s capture of a Pend d’Oreille bow, arrow, and quiver during a night raid on a combined Flathead–Pend d’Oreille camp in 1862. Other images on the same robe indicate White Grass’s capture of bows, arrows, and quivers from the Gros Ventre des Prairie on another raid, too.33 However, while some bows may have been obtained from other regions, most Plains bows were likely made from locally available materials.

Aboriginal bow makers, especially in the Plateau region but also in the Northern Plains, created a third category of bows. These were also sinew backed, but mountain sheep horn or elk antler replaced the wood for the belly of the bow, because these materials can endure far greater compression than wood. Combining a sinew backing with a horn or antler belly made a desirable bow, but horn or antler were difficult to obtain in the proper quality, and manufacturing them into a bow was an extremely time-consuming and laborious task.34 Alexander Henry the Younger observed:

The Horn bow is made out of a slip of the Horn of the Grey Ram [mountain sheep]. The outside is left untouched, when it is overlaid with several successive laying of sinew & Glue, for the thickness of about one third of an inch, and over all a coat of the skin of the Rattlesnake. The inside is very smoothly polished and displays several ridges of the Horn [i.e., traces of these ridges were still visible in the structure of the material but could no longer be detected by touch because the belly of the bow was worked level and polished smooth]. These bows are about three feet long, very neat, and will throw an arrow to an amazing distance.35

Their small dimensions made these bows appear like toys, but contemporary bow makers have manufactured very powerful weapons of dimensions similar to the original artefacts, using the same materials and largely the same manufacturing methods as the original bow makers.36

Henry also recorded important details in regard to the care and maintenance of sinew-backed bows: “To preserve those bows demands great care and attention from the owner, as in hot weather the sinew bow, whether Horn or Cedar, becomes too much braced, and in moist weather too much relaxed, as the sinews are but seldom so justly proportioned as to compress with the strength of the Horn or Wood which frequently causes it to warp, whereas the simple wooden bow requires no particular care and is at all times ready for service.”37

To apply the sinew, bow makers used various types of glues made from animal parts. The most common glue was made from hide scrapings, but fish bladder glues were sometimes used as well. The sinew and glue were applied wet. As they began to dry, the sinew clung to the wood or horn and shrank, usually pulling the bow into a reflex, which increased the amount of energy the bow could store when drawn.38 However, sinew backings were affected by changes in temperature and humidity, especially since the glues used in their application were water soluble. Too much humidity would eventually make the bow sluggish and unresponsive. I have noticed with my own reproductions of sinew-backed wooden bows that they lose some of their draw weight in humid weather. Conversely, I once left a strung sinew-backed ash bow exposed to the hot summer sun for too long and it lost much of its original reflex, which since then it has not recovered. Gluing snakeskin to the back of a bow could help to protect a sinew backing from moisture, or even rain.

Unequal amounts of sinew on each limb can cause a bow to warp. To counteract this, the Canadian bow maker Jaap Koppedrayer, for example, goes so far as to weigh the sinew before it is glued to the bow, to ensure that exactly equal amounts of sinew are applied to each limb.39 Contemporary users of horn bows in South Korea, where traditional archery is a popular competition sport, spend much time adjusting the bend of their horn bows after stringing, using heat and pressure. They store their bows in humidity- and temperature-controlled cabinets in their clubhouses and use various heating and bending devices to adjust the bend of their bows after each stringing, before the bows can be used. Reproductions of North American Plains-Plateau horn or antler bows require such adjustments to a much lesser degree than Korean composite bows. However, they still need to be checked for proper alignment of the limbs after each stringing and before shooting commences.

Even though sinew-backed bows were labor-intensive to make and required much care and maintenance, there was a decided advantage to their use. For example, the Hidatsa bow maker Henry Wolf Chief related to ethnographer Gilbert Wilson in 1911: “To one used to a wooden bow, a Rocky Mountain sheep horn [bow] would seem easily bent, but it had a relatively powerful cast. One unaccustomed to such a bow would be surprised at the range it had. After he had used one for a while he would find it hard to adapt himself again to a wooden bow. A big horn bow could be used in war and hunting. It was a powerful weapon, better than wooden bows. But it was a very costly weapon.”40

In the summer of 2010, I met the bow maker Francis Cahoon from the Flathead Reservation in Montana. He manufactures sinew-backed bows of Rocky Mountain sheep horn and gave me the opportunity to shoot such a bow, which I had never done before. The bow that I brought along to this meeting was a self bow of Osage orange wood, which I had made in the style of Native American bows from the Southern Plains. It had a draw length of ca. 61 centimeters (24 inches) and a draw weight of ca. 23.6 kilograms (52 pounds). This bow represented the upper end of what my physical strength and level of expertise could accommodate in terms of shooting. Francis Cahoon gave me one of his sheep horn bows to try. At ca. 66 centimeters (26 inches) of draw, it pulled well over 27 kilograms (60 pounds). However, its draw weight felt much lighter than that of my own Osage orange self bow. My experience was exactly as outlined by Wolf Chief in 1911, and after a long afternoon of shooting such a wonderful and elegant horn bow, it was hard to give it back and to return to my own sturdy Osage self bow.

The Inverted Plains Bow and Other European Misconceptions

By the time anthropology emerged as a scholarly discipline in North America, military archery had been out of use in Europe for over two centuries. However, during the late nineteenth century, archery experienced a renaissance as a sport, in both Europe and North America. This new enthusiasm was spurred on by the writings of two Americans, Maurice and Will Thompson. As veterans of the Confederate forces in the American Civil War, the Thompson brothers were not allowed to own firearms after the war. Because of this, they made their own bows and arrows to hunt with in the Florida Everglades. Maurice Thompson eventually began to write and publish about their hunting exploits, and his writings met with great success.41 At a time when national parks were being created in the United States and in Canada, and when the middle classes were discovering the outdoors, the Thompsons’ stories of adventure, woodcraft, and hunting became an inspiration to many. Although their writings were full of allusions to North America’s Indigenous people, the Thompson brothers’ archery was in fact rooted in Anglo-Saxon traditions.42

In that period, popular opinion in Europe and North America held that European technology and weaponry, including archery, was far superior to anything Native American. This view was supported by a selective emphasis on documents that portrayed Aboriginal archery in rather negative ways over other accounts describing Aboriginal bows and arrows as formidable weapons. Such ethnocentric views had deep roots in the past. For instance, when Sir Francis Drake encountered Aboriginal people on the California coast in 1579, he was rather unimpressed with their archery: “Their bowes and arrowes (their only weapons, and almost all their wealth) they use very skillfully, but yet not to do any great harm with them, being by reason of their weakness more fit for children than for men, sending the arrowes neither farre off nor with any great force.”43

Military archery had still been in general use on English warships only three decades earlier and continued there into the 1580s.44 For example, over 130 longbows and over 3,500 arrows were recovered from the warship Mary Rose, which sank in 1545 and was raised again in 1982.45 Judging by reproductions made of these bows, they likely had very high draw weights, between 40 and 50 kilograms (80 and 100 pounds), which enabled them to propel armor-piercing arrows for 200 meters or more. Drake and other explorers were interested almost exclusively in the potential harm Indigenous weapons could cause in battle. While Drake acknowledged the skill of Californian archers, he was not impressed with the performance of their weapons, overlooking the fact that they were primarily made to take deer and smaller animals, often at very close range. Drake did not recognize that coastal Californian people had no access to the long and straight yew staves necessary to make a so-called proper English bow. They had to content themselves with juniper and yew scrubs and other bushes and small trees. This forced them to make short and wide sinew-backed bows, which were an ingenious and efficient adaptation to the local environment.

During the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, researchers seeking proof of European technological superiority over Indigenous people cited accounts like Drake’s, overlooking his contemporaries, such as Martin Frobisher, who had encountered the formidable archery of Indigenous peoples in the Arctic and on the East Coast of North America. They read such accounts with little attention to the cultural context and environmental constraints that led Aboriginal people to develop their own unique forms of archery. Ideas of cultural relativism lay still ahead in the future.

More than three centuries after Drake, another enthusiast of the English longbow commented on his firsthand experiences with Californian Aboriginal archery. Dr. Saxton Pope acted as physician to a Yana or Yahi man who came to be known as “Ishi.” He had appeared out of California’s scrubland near Oroville in 1911, likely the last survivor of his community. Ishi came under the tutelage of Dr. Alfred Kroeber, who employed him at the University Museum of Anthropology in San Francisco as a janitor. Kroeber and Pope, an avid archer and hunter, took Ishi on hunting trips into his old homeland in the Mount Lassen area. Ishi also made bows and arrows at the museum, where Pope and Kroeber documented his work in great detail.46

After Ishi’s death in March 1916, Pope began to manufacture his own archery equipment. He built European longbows, which he compared to Ishi’s bows as well as to a wide range of other Aboriginal bows from the museum’s collection in San Francisco. This study was groundbreaking because of its practical approach.47 However, Pope’s tests were badly flawed. His sole criterion for evaluating a bow was the distance it cast an arrow. The greater its cast, the more highly Pope ranked it. Since not every bow was originally intended for distance shooting, these tests took Indigenous archery systems out of their cultural context, especially because Pope used the same arrow for all his tests, instead of using those arrows that actually belonged to each of the bows he tested.48

Furthermore, Pope compared his newly made longbow to old Aboriginal bows that had not been strung and shot in decades and had often suffered mishandling while in storage or on display. Several of the bows were damaged or had even broken during testing. Under the circumstances it is amazing that these Aboriginal bows performed as well as they did. However, if the weapons could not reach the range of his prized longbow, even when they were not designed for it, Pope dismissed them as inferior. The introduction to Pope’s study sheds some light on the views that informed his work: “A contest of strength between peoples will always interest human beings; rivalry in the arms and implements of war is one of the fascinations of national competition. It is therefore a matter of interest both to the anthropologist and the practical archer to know what is the actual casting quality and strength of the best bows of different aboriginal tribes and nations of the world.”49

The allusion to competition between nations in regard to military technology, combined with Pope’s very negative conclusions about Indigenous archery in comparison to the archery of medieval Europe, indicate the social Darwinist views that informed Pope’s work. In the course of his 1923 study, Pope tested a very long Native Paraguayan (rain forest) bow, made from a wood species that he referred to as “ironwood.” Pope considered this tropical hardwood to be an excellent material for bow making, but he was disappointed with this bow’s sluggish performance. Not taking into account the dampness and greater humidity of the rain forest environment that this bow had originated in, which made the greater length necessary, Pope shortened and retillered the weapon to follow the lines of an English longbow, to improve its cast. Afterward he remarked: “This demonstrates what intelligence can do in the bowyer’s art.”50 However, if returned to its place of origin in the rain forest, this reworked bow would probably have performed inadequately.

Researchers continue to credit Pope’s study because of its practical aspects, and often fail to recognize its flaws and cultural bias.51 Pope’s writings influenced scholarly and popular opinions on Aboriginal archery for decades, fostering a tendency to dismiss Aboriginal archery gear as largely inefficient and much inferior to East Asian and European bows and arrows and especially firearms. Forrest Nagler, whose writings contributed to popularizing bow hunting in North America based on Anglo-Saxon traditions, reinforced this tendency. In 1937 Nagler cited Saxton Pope as an important influence on his work, stating: “Native bows all over the world are usually very inferior.”52 Even as late as 1970, Robert Heizer, commenting on the “general inferiority of the American Indian bow,” wrote in regard to the archery involved in encounters between coastal Californian peoples and the Drake expedition in 1579: “The English at the time were equipped with the famous longbow, and this was clearly a superior weapon to the California Indian’s bow. No English bows of this period have survived, and the only reliable information [my emphasis] we have on these comes from experiments made by Saxton Pope, about 1920.”53

Gilbert L. Wilson was one of the few early twentieth-century ethnographers with a practical understanding of archery. He was an accomplished archer, using European equipment. Although he had little experience in actual bow making, he was one of the few outside observers who could appreciate and evaluate the information he obtained from a practical perspective. Unlike Pope, Wilson did not dismiss features of Aboriginal archery he did not understand, but described them carefully. One such feature was the marked asymmetry of many Hidatsa bows.

Wilson documented Mandan and Hidatsa culture in North Dakota from 1906 to 1918. He obtained information on Northern Plains archery from the Hidatsa elder Henry Wolf Chief, who not only had hunted and fought using archery equipment but also was an accomplished maker of bows, arrows, and strings. Wolf Chief told Wilson that among the Hidatsa the upper limb of a bow was usually made longer and thinner, with a greater bend than the lower limb. Wolf Chief stated: “Shaping the bow thus made the upper arm springier than the lower, which was relatively more stiff, and heavy. Our object in making a bow thus, was to secure steadier and straighter flight for the arrow. We felt very sure that this shape of the bow was a distinct help. That bow of yours [G. L. Wilson’s], which you say is an English bow, has both arms of equal strength. We Indians would have considered such a bow useless. I could not use such a shaped bow at all.”54

Fig. 13. Asymmetrical ash bow made by Wolf Chief, collected by Frederick Wilson before 1918. Its length is 125 centimeters. The upper arm of the bow with the permanent tie of the bowstring is on the left. Photograph courtesy of the Minnesota Historical Society, MHS 9598.22.

Fig. 14. Stringing method for asymmetrical Plains bows used by the Hidatsa, Omaha, and other Aboriginal groups in the Northern and Central Plains. The small drawing below shows the position of the archer’s right hand when pulling the bowstring into its notch on the lower end of the bow. Adapted from a photograph of Wolf Chief (Minnesota Historical Society) taken in 1911. Drawing by Roland Bohr.

Fig. 15. Asymmetrical sinew-backed Hidatsa bows, shown upside down. The bow on the left (cat. no. 8418, USNM) was made of hickory; its length is 104.14 centimeters. The bow on the right is of horn and is 91.44 centimeters long. The original drawings were detailed enough to show the slip nooses of the bowstrings on the shorter, less bending bow limbs, which are usually the lower and not the upper limbs.

Fig. 16. Asymmetrical Blackfoot self bow, shown upside down, as in Saxton Pope’s book. Note the slip noose of the bowstring on the limb with the lesser curvature.

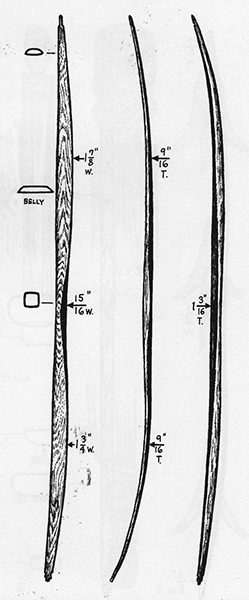

Fig. 17. Asymmetrical sinew-backed Plains bow of ash, made by Roland Bohr in 1995. The upper arm of the bow has the greater bend and length. Drawing by Margaret Anne Lindsay.

Wilson remarked that he did not understand this design feature, but wrote that a Sioux man had given him the same explanation for it as Wolf Chief.55 Often, western European bows, as well as Aboriginal bows from the Great Lakes region, also have a slightly longer upper limb, to compensate for the handgrip. However, even though slightly different in length, both arms are usually of equal strength.

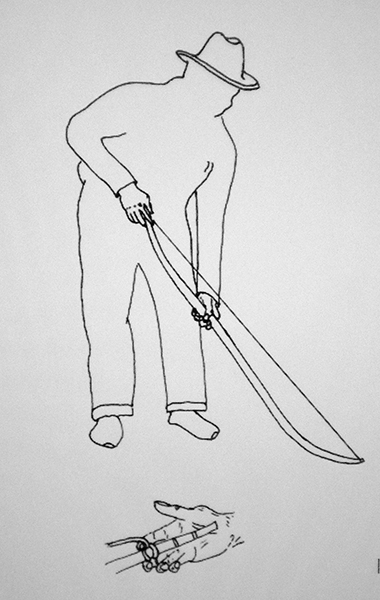

The asymmetry of these Mandan and Hidatsa bows allowed for a stringing method that differed from European stringing methods. Asymmetrical bows from the Mandan and Hidatsa carried the permanent tie of the bowstring at the top of the bow, not at the bottom as in English bows. Wilson described this clearly in his field notes: “It will be noted by any archer trained in the English school that the ‘eye’ [the slip noose of the bowstring] runs on the lower arm instead of the upper, as with us. It will also be noted that that the permanent tie is at the end of the upper arm, instead of on the lower horn, as in English archery.”56

This positioning of the bowstring made it possible to string the bow very rapidly, which allowed an archer on foot to quickly prepare the bow for shooting when sighting game or enemies. The archer held the bow in the left hand, gripping it at the handle with the back of the bow pointing forward. Then he merely bent down at the waist, setting the upper end of the bow on the ground, while pressing down at the handle with the left hand and pulling the slip noose of the bowstring into place on the lower limb of the bow with the right hand. A practiced archer could string a bow and have an arrow on the string, ready to shoot within a few seconds.57 Unfortunately, this information remained largely inaccessible because Wilson’s field report remained unpublished until 1979.58

Long before Wilson’s work with the Hidatsa, other ethnographers had already made the erroneous assumption that in regard to tying the bowstring, North American Aboriginal bows were generally similar to European bows. They concluded that the arm of the bow with the permanent tie of the bowstring was the lower arm. This led to a misunderstanding and misrepresentation of asymmetrical Plains bows. For example, in 1893 the anthropologist Otis Tufton Mason published a report on North American Indigenous archery equipment, based on his examination of bows, arrows, and quivers in the collections of the Smithsonian Institution. This report included illustrations of two asymmetrical bows collected from the Hidatsa, depicting them as strung and upside down. Mason described one of these sinew-backed bows: “Bow—made of hickory, with a double curve—the lower curve larger than the other.”59

In the early 1920s, Saxton Pope tested an asymmetrical ash bow collected from the Blackfoot.60 Because this self bow did not have a string, Pope supplied his own when he tested this weapon. When bracing the bow he correctly put the permanent tie of the string on the limb with the greater curve. However, the illustration in his book shows the bow upside down, the limb with the greater curve pointing downward, just like the asymmetrical Hidatsa bows in Mason’s Smithsonian report.

Since Pope illustrated and likely shot the bows he tested with the permanent tie of the bowstring at the bottom, it is possible that he tested this Blackfoot self bow upside down. The bow still cast Pope’s test arrow an astonishing 145 yards without breaking. However, Pope was not impressed and wrote about this specimen: “If this is the type of a Plains Indian hunting bow, that bow was a poor one.”61 Based on such observations, Pope concluded: “The aboriginal bows are not highly efficient, nor well made weapons.”62

This error in regard to the orientation of the asymmetrical Plains bow has persisted into some recent publications on North American Aboriginal archery that still depict these bows upside down.63 Only a few researchers with access to Wilson’s field notes recognized the asymmetrical Plains bow as a distinct type.64 From 1994 to 1996, one such researcher, the North Dakota bow maker and artist Ron Taillon, manufactured working reproductions of asymmetrical Plains bows based on the field notes of Wilson and Wolf Chief. These bows were used with the longer, more curved limb upward. His experiments verified Wolf Chief’s statements about the asymmetry of the bow causing a flatter trajectory of the arrow. A flat trajectory makes aiming much easier and enables an archer to shoot directly at targets up to 40 meters’ distance without having to compensate for an arched trajectory of the arrow as would be necessary with more symmetrical bows.65 Taillon’s work was published in a traditional archery magazine and also in a German magazine of North American history, but it remained largely inaccessible to scholars of Aboriginal history and anthropology. The view that asymmetrical Plains bows were badly constructed and hardly functional, due to the “lower” limbs being warped, remained firmly in place.

Although they were far from being the only bow type among Aboriginal people of the Northern Plains, asymmetrical bows were quite common and were used by various Aboriginal groups, including the Sioux, Cheyenne, Mandan, Hidatsa, and Blackfoot. However, researchers consistently emphasized asymmetrical bows as examples of faulty design and craftsmanship and then applied these negative views to Northern Plains Aboriginal archery in general.66

Because Mason’s and Pope’s works have been so influential in shaping views on the subject, researchers unfamiliar with the practical aspects of archery and bow making have often uncritically accepted them. Even when Aboriginal people manufactured bows and arrows under the observation of non-Aboriginal researchers, the researchers often did not understand and thus did not accurately record what they saw. Adding to the problem, information provided by elders, who were still familiar with traditional skills, was often translated by younger persons who had much less familiarity with their people’s archery. Then non-Aboriginal observers with little knowledge of the topic recorded this information and went on to make interpretations that were highly misleading.67

Some Bow Types of the Central Subarctic

While the dramatic image of the mounted Plains Indian hunter using a short bow in the pursuit of buffalo has been deeply ingrained in popular representations of Native Americans for at least a century, the Indigenous people of the Central Subarctic have not been particularly noted as archers. This perception appears to be based to some extent on three factors. First, firearms were more readily available to Aboriginal people of the Hudson Bay Lowlands and adjacent regions to the south and west at a much earlier stage than they were to people in the Northern Plains. As a consequence, historians and ethnographers tended to assume that Aboriginal people of the Central Subarctic discarded most of their traditional weaponry in favor of European firearms and metal weapons soon after these became available.68

Second, the Central Subarctic environment is not home to trees that are ideal for bows. Prime raw materials for bow making—eastern hardwoods like ash (Fraxinus americana), black locust (Robinia pseudoacacia), hickory (Caraya cordiformis), and Osage orange (Maclura pomifera)—are not available in the region. The Omushkego-Cree, for example, mainly relied on tamarack (Larix laricina), birch (Betula spp.), and black spruce (Picea mariana) for bow making.69 Neither wood is ideal for bow making, due to their lack of tensile or compressive strength.70 Extreme cold was also a problem for Aboriginal archers. Louis Bird and other Cree elders noted that the extremely low temperatures in the Central Subarctic from about December to early March made bows and arrows unusable because they would freeze stiff, lose their elasticity, and break when under tension and compression stress.71

Finally, documentation on Indigenous archery in the Subarctic, especially for northern Cree and northern Ojibwa peoples, is also rare. Ethnological reports rarely mention archery in any great detail, and material culture collections from the Subarctic usually contain few archery items. When I met Louis Bird at the University of Winnipeg in 1999, we began to discuss many aspects of traditional Omushkego-Cree technology, including archery. Louis shared much information on this subject with me, which no previous researchers had asked him about.

Fig. 18. Self bow collected from Nelson House Cree in northern Manitoba before 1941. Charles Clay Collection, Manitoba Museum, Winnipeg, H4.12.12. The top drawing shows the back of the bow; the drawing below shows the side view. Edges on the back and belly have been beveled. Growth rings on the back have been cut through and appear as chevrons and ovals. The maximum length of this bow measured along the back is 123.2 centimeters, the maximum width at the handle is 30 millimeters, and the maximum thickness at the handle is 20 millimeters. Drawing by Roland Bohr.

Fig. 19. Omushkego Cree self bow as described by Louis Bird. Such bows were typically from 140 to 160 centimeters long. Top: The bow is unstrung, with the belly of bow facing up. Bottom: The bow is strung and ready for use. Center: The back or outside of the bow shows one continuous uncut growth ring. Drawing by Roland Bohr.

Fig. 20. The Sudbury bow. This hickory self bow is just over 170 centimeters long and, except for the wood, shows remarkable similarity to bow designs of the Swampy Cree, as outlined by Louis Bird. The left image shows the belly of the bow with chevron patterns from tillering. Drawing by Steve Allely, reproduced here with the artist’s permission.

Fig. 21. Ingalik self bow from western Alaska. The bow is 167.5 centimeters long and 3.51 centimeters wide at the widest point of the limb. The right drawing shows the bow seen from the side; the left drawing shows the back of the bow, with cross sections. Note the similarity to the bow design described by Louis Bird (Fig. 19), as well as the Sudbury bow (Fig. 20). Museum of Ethnology in Berlin, Germany (Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Ethnologisches Museum IV-A-5602). Drawing by Roland Bohr.

All the Central Subarctic bows examined for this study were collected in the twentieth century. These self bows are usually made from birch or coniferous wood and are widest at the handle area with a very gradual taper toward the tips. Their cross sections are almost rectangular, with the greatest thickness occurring in the handle area, gradually tapering in thickness toward the tips. Even though their dimensions make them appear quite stout, they were made from rather lightweight woods with little mass.

Although all the Subarctic bows examined for this study were self bows, the anthropologist Alanson Skinner mentioned in his 1911 report that the Swampy Cree had used short, sinew-backed bows in the distant past.72 Cree elder Louis Bird also mentioned a kind of bow backing used by his people that he called “sturgeon spine” or “sturgeon sinew.” He did not seem to be familiar with the concept of sinew backing, either by gluing shredded sinew to the back of the bow with hide glue, as was practiced in the Plains and Plateau, or by applying a cable of braided or twisted sinew fibers to the back of the bow, as was done by several Inuit groups and some Aboriginal people in the U.S. Southwest.73 However, when shown a drawing of a southern Alaskan Inuit bow, he said that this was how such bows looked, in terms of the way the backing was applied and the front-view profile of the bow. The illustration showed a more or less straight, but wide and flat, wooden bow with a simple single sinew cable backing (see Fig. 24).74

According to Mr. Bird, Omushkego-Cree people used to make relatively long, flat self bows, preferably from tamarack. An intact, uncut growth ring usually formed the back of the bow. In front-view profile, these bows were narrow in the handle, gradually widening until they reached their greatest width at the middle of the bow limb, where the greatest tension and compression stress occurred. From there they tapered toward the tips.

If a backing was to be applied, a shallow groove with a semicircular cross section was cut into the center of the back, parallel to the longitudinal axis of the bow and running from one tip to the other. The backing was then placed into this groove, wrapped around the tips, and secured to the bow by means of wrapping with rawhide. The fact that the groove was semicircular in cross section suggests that it must have been made in order to accept material with a rounded cross section, such as a cordage cable.75

However, Mr. Bird expressed unfamiliarity with cable-backed bows of any type and said that he had not observed bows with a “sturgeon spine” backing in action; he knew about them mainly through his father, who had apparently owned such a bow in his youth. But he added that even the bows with a sturgeon spine backing could not be used in extremely cold weather because they would lose their elasticity and break when drawn. Therefore, during caribou drives in the winter, hunters would warm their bows over a low fire behind a hunting blind constructed from rocks and snow, while waiting for the caribou to be driven into an enclosure or pound by other hunters.76

Anthropologist Edward S. Rogers, writing on the material culture of the Mistassini Cree, also mentioned the use of wide-limbed flat bows that were about 97 to 127 centimeters (381/8} to 50 inches) long. The drawings he presented of such bows were similar to the drawings based on Mr. Bird’s descriptions (Fig. 19), but Rogers stated that these bows, made of tamarack, birch, or black spruce, were self bows and did not have any backing.77

This bow design with wide, long, and flat limbs is similar to that of one of the oldest North American bows from the postcontact period, collected in 1660 in Sudbury, Massachusetts. It was made from hickory and is 170.21 centimeters (671/8 inches) long.78

Ingalik self bows from western Alaska, collected in 1882–83 by the Norwegian ship captain Johan Adrian Jacobsen for the Museum of Ethnology in Berlin, Germany, exhibit a similar layout.79 These wide-limbed flat bow designs were much better suited to distribute tension and compression strain more evenly, especially if wood species with low compression and tension tolerance had to be used.80 However, it is not clear whether this design was in general use from the Eastern Seaboard to the boreal forest, and as far west as the west coast of Alaska, before the widespread adoption of firearms.

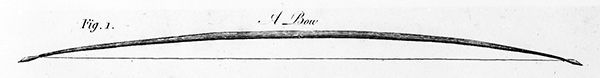

Fig. 22. Indian bow by James Isham, 1743. Pen and ink drawing. Isham’s caption read: “An Indian Bow of Berch [sic]. The Arrow with a Sharpe Iron at the End.” Image courtesy of the Hudson’s Bay Company Archives, Archives of Manitoba, Winnipeg (HBCA E.2/1 fo. 73d).

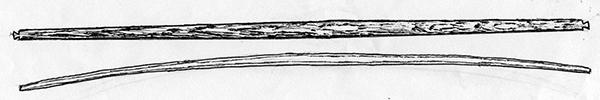

Fig. 23. Samuel Hearne’s drawing of a Déné self bow, titled “Indian Implements.” Plate 5 in Hearne’s Journey . . . to the Northern Ocean (Dublin edition of 1796 reprinted in 1968). HBCA 1987/363-S-79/21.

![]()

Fig. 24. Western Arctic type of sinew cable–backed Inuit bow. The bow limbs are widest where the greatest bending stress occurs.

When ethnographers and anthropologists began their work with Central Subarctic Aboriginal peoples during the early twentieth century, bows and arrows had already fallen out of use as weapons for big game hunting and combat and were mainly used to hunt small fur-bearing animals and birds.81 Therefore bird blunts became the most common type of arrow collected from Central Subarctic people during this period. Central Subarctic Aboriginal people also sometimes made archery artefacts for anthropologists, in order to demonstrate what the local archery had been like in the past. When the anthropologist John M. Cooper briefly visited Ojibwa communities at Lake of the Woods and Rainy Lake in northwestern Ontario in September 1928, two of his Aboriginal coworkers made archery outfits for him and pointed out that weapons like the ones they had made had been in use among their people until recently.82

No bows from early Central Subarctic communities appear to have survived. However, the Hudson’s Bay Company fur trader James Isham included a drawing of a Swampy Cree bow and arrow in his mid-eighteenth century observations on Hudson’s Bay.

Samuel Hearne, too, included an illustration of what was probably a Déné self bow from northern Manitoba in his mid- to late eighteenth-century travel reports.

The image shows a low-strung, relatively long bow with a single curve, similar to surviving bows that were later collected in the region. The diamond-shaped nocks on the ends of the bow in Hearne’s illustration are particularly reminiscent of those found on other Subarctic self bows. Unfortunately, neither James Isham nor Samuel Hearne included drawings showing these bows from the back. Thus, it is not possible to compare them to Louis Bird’s descriptions of older Swampy Cree bows.

I have so far not been able to trace any surviving Central Subarctic bows that were collected during the 1700s and early 1800s, when Indigenous distance weapons were giving way to European firearms. The few surviving bows collected from Aboriginal peoples during the seventeenth century in what is now the eastern third of the United States are similar in shape to the bows described by Mr. Bird, but they were made from hardwoods such as hickory.

Descriptions of Arctic Inuit bows, however, offer some contrast to those just discussed. Northern Cree and Déné peoples on occasion entered into combat against Inuit people and encountered these rather different weapons. Furthermore, European travelers and sojourners in the Hudson Bay region sometimes encountered Inuit and Cree or Déné and left descriptions of their hunting equipment. Because arctic bows were often made from woods with low tensile strength, the Inuit skillfully added a sinew backing that consisted of a very long strand of braided sinew, wrapped back and forth from one bow tip to the other and secured to the back of the bow through various knots and half-hitches.83

The formidable power and ingenious craftsmanship of Inuit bows inspired European observers, such as the chroniclers of the Frobisher expeditions, to leave relatively precise descriptions of these weapons and their capabilities. In contrast, they commented far less frequently and favorably on the archery of the Hudson Bay Lowland Cree and the Chipewyan. As mentioned earlier, little information regarding Cree archery gear from the seventeenth to the early nineteenth century has been recorded. Most information on Subarctic archery comes from the early to mid-twentieth century, when it was no longer commonly used for big game hunting, and from the memories of elders such as Louis Bird. These accounts indicate that self bows were in general use among Central Subarctic Aboriginal peoples. Although we have hints about the manufacture and use of sinew-backed bows among the Lowland Cree, it seems likely that they did not adopt the use of sinew-backed bows on a large scale.

The “Penobscot War Bow”: A Traditional Bow or an Invented Tradition?

The interpretive challenges that bows and their images present come to the fore in the case of the making of the 1930 motion picture The Silent Enemy. Madeline Katt Theriault, an Ojibwa woman from Bear Island, Lake Temagami, Ontario, participated in the film as one of the many Aboriginal people hired as extras, and she left an autobiographical account of her role in it.84 Besides acting, Theriault also made many of the costumes used in the film. After the filming, Theriault participated in an ethnographic pageant, portraying traditional Northern Ojibwa culture, put on for visiting tourists and held at Bear Island. Mr. A. Goddard, then the owner of the Temagami Hotel, filmed this pageant in 1938. Theriault stated that several local Aboriginal men and boys made archery gear for the pageant and demonstrated its use to the tourists.85

Although performed by actors largely unfamiliar with life in the bush, the snaring methods shown in the movie The Silent Enemy closely corresponded to snaring methods used by actual Subarctic hunters and recorded by the anthropologist John M. Cooper in the 1930s.86 However, the bows used in the movie reveal some interesting diversity. Most of the male supporting actors carried bows corresponding to the twentieth-century Subarctic self bows discussed previously. In contrast, the actors playing the two main characters carried bows of a rather rare design, supposedly coming from the Penobscot of present-day Maine.87 This design consists of a shorter and a longer wooden bow lashed together at their handles, so that the belly of the shorter bow rests on the back of the longer bow. The tips of the smaller bow are connected to the tips of the longer bow by strings. When the large bow is drawn, the smaller one on its back absorbs most of the tension strain of the larger bow. Some modern bow makers believe that this bow design considerably relieves tension stresses.88

The two “Penobscot” bows were actually used in the film, but only one Subarctic self bow was shown in action. Although the actress Molly Spotted Elk (Nelson), who played the female lead in the movie, was actually Penobscot, the “Penobscot” bows in the film may have been misplaced artefacts. If so, they were among many others: the movie was filled with paraphernalia belonging to other cultures, such as Plains war bonnets, porcupine quill-embroidered shirts from the Northern Plains, and women’s dresses from the Southern Plains.89

The American Museum of Natural History and the University of Pennsylvania Museum for Archaeology and Anthropology hold most of the few original bows of this type in existence today. Their records indicate that at least three of these bows were collected from a Penobscot elder by the name of Gabriel Paul in Maine during the 1920s and 1930s. Paul may have manufactured most if not all of these bows. The rarity of this bow design outside Maine, and the fact that most of these bows were probably made by the same person, suggest that this design does not reflect a widely adopted approach to bow making used by Aboriginal people throughout the eastern half of North America, but rather represents an individual’s favorite bow design.90 Nonetheless, various publications on Aboriginal peoples of northeastern North America treat it as a genuine artefact of Penobscot culture that was in widespread use at some point in the past.91 Contemporary manufacturers of traditional archery gear even advertise their Penobscot bows as having “evolved over 1,000 years as a Moose bow, and a weapon to ward off invading ships entering the harbor.”92

Fig. 25. So-called Penobscot double bow. This bow, made by Gabriel Paul, was a gift of Dr. Samuel Fernberger to the University of Pennsylvania Museum in Philadelphia in 1933 (accession no. 33-3211 UPA). Drawing by Steve Allely, reproduced here with the artist’s permission.

These examples demonstrate how a combination of a lack of information, misunderstanding, and ethnocentrism has contributed to the emergence of uncritical views about Aboriginal technology and weaponry. Non-Aboriginal scholars in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century frequently applied “knowledge” gained through studies such as Saxton Pope’s in comparisons of European metal and firearms technology. When evaluating Aboriginal military and hunting technology on such a basis, writers might praise the Penobscot bow but would dismiss other items as being inferior to European technology, rather than recognizing their sophistication and their adaptability to local conditions and needs, and their integration into local cultural contexts.

The next chapter will examine different types of arrows used with these bows. It will highlight Aboriginal adaptations of European-introduced materials such as metal arrowheads, and the complementary use of them in tandem with Aboriginal technology.