Arrows and Arrow Makers

Aboriginal Plains and Subarctic arrows show a wide range of types adapted to a variety of purposes. Uses of European-introduced materials such as metal for arrowheads exemplify the complex ways Aboriginal people combined European materials with their own technology to create articles uniquely suited to their needs. A look at the social aspects of arrow making and arrow use contributes to our understanding of these developments.

The bow and arrow form a combined weapon system. While the bow propels the arrow, it is the arrowhead that accomplishes the desired effect on the target. Aboriginal archers knew that in an emergency they could fashion a crude bow from almost any strong sapling, small tree, or branch, but making well-balanced, true flying, dependable arrows was another matter. The Hidatsa arrow maker Henry Wolf Chief told the ethnographer Gilbert Wilson in 1911, “A good arrow could not be made in a hurry.”1

Despite the seemingly simple appearance of an arrow, arrow making was a highly complex process that demanded great skill and knowledge. To assure consistent shooting, the elasticity of every arrow shaft had to match the draw weight and the draw length of the bow, and the finished arrows had to be as uniform in size and weight as possible.2 Therefore, when shaping the arrow shaft, the maker had to keep in mind the weight of the arrowhead, the fletching, the sinew wrapping, and the glue before the different parts of the arrow were assembled, in order to achieve the correct weight for the finished arrow. Because the weight of each component influences the flight characteristics of the completed projectile, all components had to be in correct proportion to one another. If, for instance, the arrowhead was either too light or too heavy, the arrow would not fly straight. All this precision work had to be accomplished without modern weighing technology. Just as clothing is often tailored to fit, a bow and its arrows had to be made compatible to the body dimensions, strength, and shooting technique of the archer.3 This was especially difficult to achieve if the maker and user of the archery gear were not the same person, as was often the case.

A close examination of changes in the manufacturing features and quality of these weapons sheds light on the changing importance of traditional weaponry in Aboriginal societies, reflecting changes in their subsistence strategies and combat methods. Surviving Aboriginal arrows in museum collections still reveal much of the ingenuity of their makers. I examined over five hundred arrows for this study. This included taking measurements of their dimensions, sketching and/or photographing construction details, and checking for uniformity in arrow sets.

Arrows of the Northern Plains

In 1833–34 Prince Maximilian observed:

The arrows of the Mandans and Manitaries [Hidatsas] are neatly made; the best wood is said to be that of the service berry (Amelanchier sanguinea). The arrows of all the Missouri nations are much alike, with long, triangular, very sharp, iron heads, which they themselves make out of old iron. . . .

They know nothing of poisoning their arrows. The arrow-heads were formerly made of sharp stones: when Charbonneau first came to the Missouri, some made of flint were in use, and in the villages they are still met with, and in all those parts of the United States where the expelled or extirpated aborigines formerly dwelt. We were told that, in the prairie, near the Manitari villages, there is a sand hill, where the wind has uncovered a great number of such stone arrow-heads. . . .

Though all arrows appear, at first sight, to be perfectly alike, there is a great difference in the manner in which they are made. Of all the tribes of the Missouri, the Mandans are said to make the neatest and most solid arrows. The iron heads are thick and solid, the feathers glued on, and the part just below the head, and the lower end, are wound round with very even, extremely thin sinews of animals. They all have in their whole length, a spiral line, which is to represent the lightning. The Manitaries make the iron heads thinner, and not so well. They do not glue on the feathers, but only tie them at both ends, like the Brazilians. The Assiniboines frequently have very thin and indifferent heads to their arrows, made of iron-plate.4

Arrows display a wide range of construction details. Because the short nineteenth-century Plains bows did not permit long draw lengths, their arrows had shaft lengths between 56 and 61 centimeters (22 to 24 inches), much shorter than arrows collected from Central Subarctic communities.5

There were two ways to make wooden arrow shafts. The first method used the trunks of large trees. The trunks were split down the middle and each half was then further split into flat planks or boards, beginning at the center of the tree, which already had a flat surface from the first split. Each plank was then split into long, squared dowels, which were planed to a round diameter. Mandan and Hidatsa people used this method, especially for war arrows made from ash, because split ash was said to yield tough and durable shafts that seldom broke.6 This method of making arrow shafts was not very common in the Plains, but was more so in areas with predominantly coniferous woods, such as the Central Subarctic and West Coast, where arrow shafts were mainly made from black spruce, cedar, or pine. However, in his 1923 study on North American Indigenous bows and arrows, Saxton Pope stated, “Aboriginal shafts are universally small straight limbs of shrubs, or reeds. . . . Seldom if ever is any attempt made to employ split timber in their manufacture. The better developed methods of arrow making, however, make use of split timber, which is later planed and turned into cylindrical shafts.”7

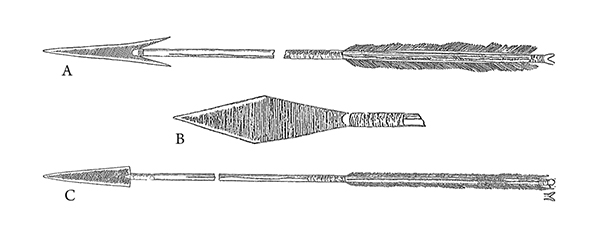

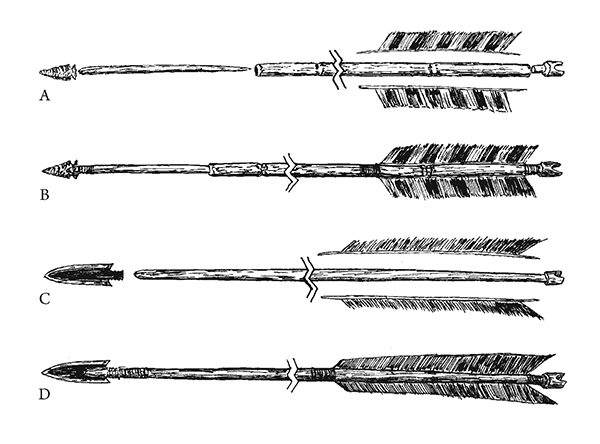

Fig. 26. Northern Plains arrows with metal arrowheads, from the second half of the nineteenth century. A: Barbed arrowheads were often used for combat. The sparse sinew wrapping of the arrowhead facilitated its detachment from the shaft so it would stay in the wound. (Sioux; collected by M. M. Hazen, Cat. No. 154016, USNM.) B: The diamond shape of this arrowhead makes removal from a wound easier, for example, after killing and before skinning an animal. (Collected by Mrs. A. C. Jackson, Cat. No. 131356, USNM.) C: An “all-purpose” arrowhead, suited for hunting and combat. These arrows have flaring, or “raised,” arrow nocks, which aided the archer when using a pinch-grip arrow release. (Hidatsa; collected by Dr. Washington Matthews, U.S. Army, Cat. No. 8418, USNM.)

The second method, which was most common in the Plains, was to use natural shoots, saplings, or branches for arrow shafts. According to Henry Wolf Chief, Hidatsa people used three species of wood to make arrow shafts. These were Juneberry (Amelanchier alnifolia, also called serviceberry or Saskatoon berry), “snakewood,” and ash.8 Other species commonly used in the Northern Plains were red osier dogwood (Cornus stolonifera), common wild rose (Rosa woodsii), and chokecherry (Prunus virginiana).9 While Plains people used every wood known to yield serviceable arrow shafts, the selection of a species largely depended upon its regional availability.

The shaft diameters of the arrows I examined ranged from 7.5 to 11 millimeters (0.29 to 0.43 inch) at the center of the shaft. Many arrow shafts were slightly barreled, meaning that they were thickest near the center and tapered toward their ends. Such a “cigar-shaped” design accomplished at least two objectives. First, it helped to reduce the weight of the shaft and thus made the arrow fly faster. More importantly, it kept the arrow shaft stiffer as it bent around the grip area of the bow when the arrow was released in shooting. A shaft that is stiffer at its center bends less and stabilizes earlier in flight than a more elastic one of equal length, because it undergoes less of a wavy sideways motion when leaving the bow.10

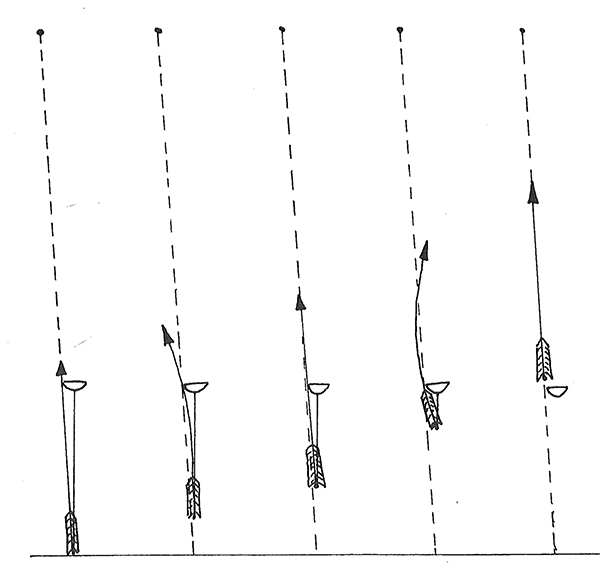

In order to illustrate this, one needs to understand the phenomenon known as “archer’s paradox,” an important part of archery physics. Robert P. Elmer, an archery writer and researcher, introduced the term “archer’s paradox” in the 1930s. High-speed photography by Clarence Hickman made the phenomenon visible in its individual stages.11

Right-handed Aboriginal archers usually placed their arrows to the left of the bow handle. Therefore the arrow had to wind around the handle in a somewhat wavy motion in discharge and would only straighten out at some distance from the bow. This caused an arrow with a too-elastic shaft to pass to the right of the target and an arrow that was too stiff to pass the target on the left. Therefore the arrow shaft’s elasticity had to be such that the arrow leveled out into straight flight as soon as possible. This meant that the elasticity of each arrow shaft had to be matched to the bow from which the arrow was to be shot. With the shorter Plains Indian arrow shafts this was less of a problem compared to longer arrows used in the Subarctic.

With few exceptions, arrows generally need to have fletchings attached at the end of the shaft to provide directional stability during the arrow’s flight. Native arrow makers most commonly used various kinds of bird feathers for fletchings. The most common fletching method was to split or strip feathers along the quill and then attach three of these split feathers equidistant to each other at the rear portion of the arrow shaft, using sinew to wrap the quills to the shaft. Some arrow makers glued the quills to the shaft using hide glue, while others only wrapped the front and rear parts of the quill to the arrow shaft. Once the feathers were attached, Native fletchers usually trimmed them down somewhat by cutting or burning off excess length of the vanes.

The long and low-cut fletching of Plains Indian arrows may have been another feature designed to stabilize the arrow’s flight as quickly as possible and enhance accuracy. When shooting at close range, stabilizing the arrow early in flight may have been more important than a slight gain in shooting distance. In mounted bison hunting or close combat, for instance, the shooting distance was often only a few meters. Therefore, in order to be aimed accurately, Plains Indian arrows had to level out almost immediately after leaving the bow. This would have been very difficult if Aboriginal archers had used the long shafts and short fletchings common in European archery.

Fig. 27. “Archer’s paradox,” or stages of the motion an arrow undergoes in discharge as it passes the handle of the bow. Drawing by Roland Bohr.

Fig. 28. Arrow releases used by Aboriginal people. A and B: Variations of the Mediterranean release, common among Algonquian-speaking peoples in the Subarctic. C: Simple pinch-grip release. D, E, F, G, and H: Variations of an assisted pinch-grip release. H is sometimes referred to as the Sioux release. I: Mongolian release, common on the Northwest Coast, in California, and among Subarctic Athapaskan peoples. The Mongolian release is also known as the thumb draw. Drawings by Margaret Anne Lindsay.

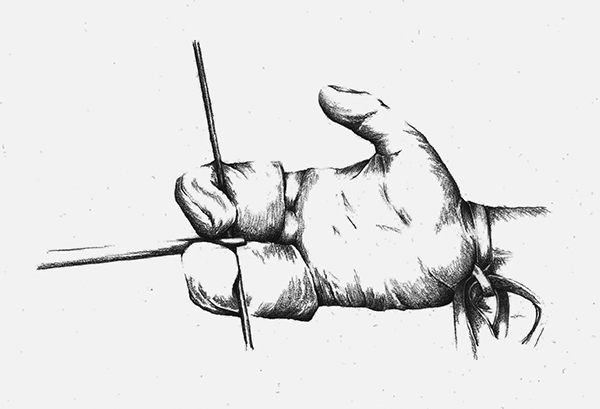

Most Plains arrows had a so-called raised nock, or flared nock, meaning that the end of the arrow shaft with the notch for the bowstring was left thicker than the shaft itself for better handling with a pinch-grip arrow release, which was common in the Plains.12 With this type of arrow release, which is ideal for shorter draw lengths, the archer holds the nock of the arrow between the thumb and the side of the index finger. From one to three of the remaining fingers are placed on the bowstring to support the thumb and index finger in pulling back the bowstring.

Misinterpreting information gathered by Saxton Pope and T. M. Hamilton, H. Henrietta Stockel argued in her book The Lightning Stick: Arrows, Wounds, and Indian Legends that arrow releases could be ranked according to the amount of impact force they supposedly made the arrow impart on the target.13 Stockel stated:

Further, the way an arrow is released from the bow also influences the type of damage it causes. Spencer L. Rogers described five forms of arrow release used by Native Americans and ranked them according to the power they generated, with the “primary” form being the weakest. . . . The primary, secondary and tertiary releases constitute a primitive type of shooting, and the Mediterranean and Mongolian types are more refined forms. Thus, according to Roger’s reasoning, tribes were more or less adept at slaying or wounding according to how they held and released their arrows.14

However, it is the energy that a bow is able to store, that is, the draw weight at a specific draw length of the bow, and not the type of arrow release, that “generates power.” The ranking of arrow releases developed by E. S. Morse and others was based on a social Darwinist approach to ranking different cultures and their achievements, portraying those cultures as more advanced that had developed bows with very high draw weights, primarily for military purposes, which made specific kinds of arrow release necessary to handle them efficiently.15 For example, the use of the Mediterranean or Mongolian release was considered necessary to draw bows of extremely high draw weights, such as some types of Asiatic composite bows or specimens of the “English” longbow of 100 pounds’ (ca. 45.4 kilograms) draw weight or more. It would be next to impossible to bring such bows to a full draw of 28 to 31 inches (ca. 71 to 79 centimeters) or more using a primary pinch-grip release. However, Native American bows usually did not have such high draw weights. Based on contemporary reproductions and their comparison to surviving original Plains bows, these weapons seem to commonly have been in the range of 50 to 65 pounds (ca. 22.7 to 30 kilograms), at draw lengths from 22 to 26 inches (ca. 56 to 66 centimeters). It is possible to use an assisted pinch grip, such as the secondary or tertiary release, to bring such bows to full draw and shoot them effectively. This is evidenced by the prevalence of raised nocks on Plains arrows, which were shaped to assist in a pinch-grip release.

Of course, the Mediterranean release could be used with these bows just as effectively. However, the type of release would not change the impact force delivered by the arrow to the target. If a bow is always drawn to its maximum draw length, it will deliver the same amount of energy to the arrow with each shot, regardless of the type of arrow release that is used. Therefore, given a bow of moderate draw weight, it is not the type of release that dictates how much energy the bow will store and transfer to the arrow, but the bow’s draw weight at a specific draw length. In this case, the release type does not influence the amount of energy that the arrow will deliver to the target. Except for the primary version of the pinch-grip release, any of the arrow releases shown in Figure 28 would be sufficient to handle bows of up to 65 pounds of draw weight. Varying degrees of damage, using the same bow and arrow, could only be achieved by using different draw lengths with each shot. If the arrow is not drawn to the bow’s full draw length, it will gather less energy and have less impact force. Thus, Stockel’s statement about different types of arrow release causing varying degrees of damage is incorrect in a Native American context. In fact, describing the shooting experiments that he and Will Compton conducted, Saxton Pope stated: “The methods of shooting were of two types. Mr. Compton shot with a Sioux release: all fingers and thumb on the string, the nock of the arrow steadied between the thumb and forefinger, the arrow discharged from the left of the bow [see Fig. 28H]. This would be classified by Morse as a tertiary type. I shot with the English release or Mediterranean type. There was no apparent difference in the cast of the bows dependent upon these conditions [my emphasis].”16

Transitions to Metal Arrowheads

Lithic projectile points formed an important component in Aboriginal weapons systems beginning in the earliest documented periods of human habitation in North America. The changing shapes and manufacturing techniques of projectile points constitute important diagnostic features in archaeology.17 Researchers have interpreted the shift from lithic to metal projectile points as a momentous change in Aboriginal material culture because projectile points from metals introduced by Europeans, such as iron and steel, were said to have quickly replaced traditional projectile points manufactured from lithic or organic materials. This supposedly influenced the military balance of power in favor of those Native communities who had access to iron and steel projectile points.18

Archaeologist Philip Duke saw projectile points as reflective of differences in male status. He argued that a craving for “newness” may have been an important rationale for the shift from one lithic point shape to another and especially for the shift from stone to metal arrowheads in the Plains, besides functional advantages of one material or shape over others.19 However, the actual spread of metal arrowheads and their influence on Indigenous archery systems is not very well understood, and the broad generalizations about this topic often found in scholarly publications and in popular perceptions need to be examined. While this technological change has been documented, the details of this transition process remain obscure.

Early on in this process, Native people may have manufactured iron arrowheads from used or discarded ironware. For example, Hudson’s Bay Company fur trader and explorer Peter Fidler observed about Pikani arrows in 1792: “Their arrows in general are shod with pieces of Iron work old kettles & old pieces of Iron battered out thin between 2 stones.”20 In 1811 fur trader Alexander Henry the Younger observed about arrows used by Native peoples of the Plateau: “The arrows these people use are much longer than those of our Indians on the eastward of the Mountains. Theirs are near three feet long [possibly indicating arrows with foreshafts; see Fig. 36], very neatly made, being slim pointed and feathered. They are shod [tipped] with Flint, but of late years, they procure Iron for that purpose, which saves them an immense deal of trouble in working down the Flint to the proper shape and size.”21

During his visit to the Mandan villages in 1806, Alexander Henry noted about Native manufacture of arrowheads: “I saw the remains of an excellent large Corn mill [provided by the Lewis and Clark expedition], which the foolish fellows [Mandan people in Black Cat’s village] had demolished on purpose to barb their arrows, and other similar uses. The largest piece of it which they could not break nor work up into any weapon they have now fixed to a wooden handle and make use of it to pound marrow bones to make grease.”22

Buffalo Bird Woman, the sister of the Hidatsa arrow maker Henry Wolf Chief, described to the ethnographer Gilbert Wilson how her father, Small Ankle, used to manufacture arrowheads from scrap or sheet metal:

In my father’s earth lodge was a stone sunk level with the floor, which Small Ankle used for an anvil. It stood near the fireplace between it and the rearmost of the posts from which swung the drying pole over the fire. I think every lodge in the village had such an anvil.

Upon his stone anvil my father pounded bits of metal he wished to straighten. Especially he used it for making iron arrow heads. He heated the iron in the fire red hot, laid it on the stone and cut out the arrow heads with chisel and hammer. Small Ankle got his iron and chisel of the traders, as also a little pair of tongs, which he used to pick up the hot iron. His hammer was made of elk horn.23

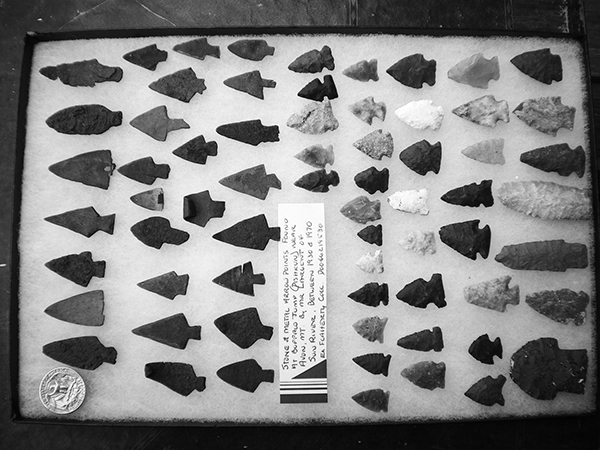

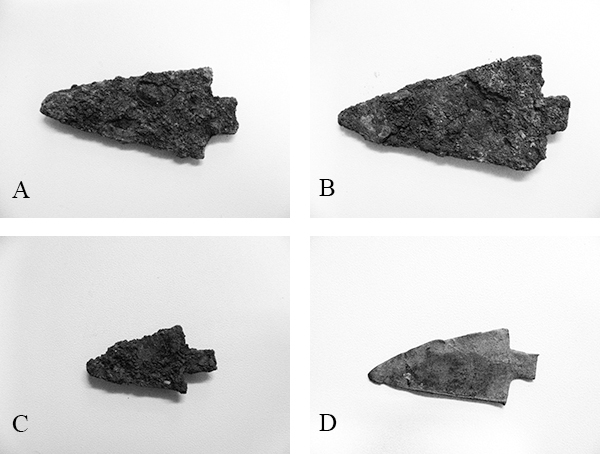

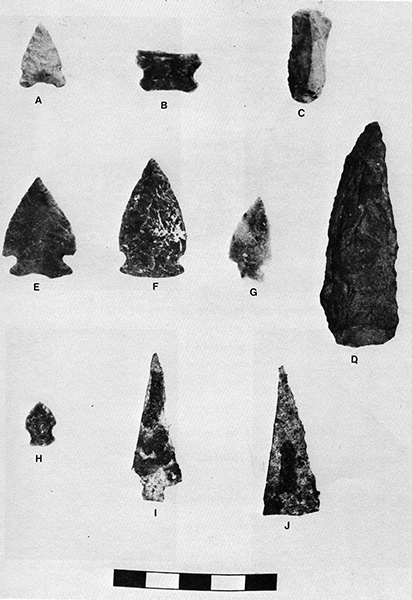

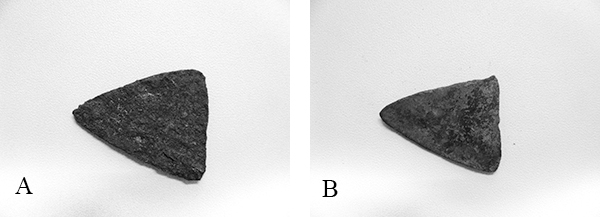

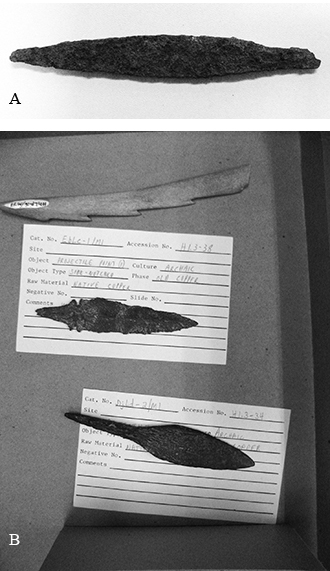

However, it is often not possible to clearly distinguish whether Native people or Europeans manufactured archaeologically recovered metal arrowheads.24 Metal arrowheads recovered from archaeological sites in the Northern Plains sometimes resemble lithic projectile points in shape, evoking their ancestry. Metal arrowheads recovered from archaeological sites in Saskatchewan, Alberta, and parts of the Upper Missouri region, indicate that projectile point size seems to have increased over time, from about 1740 to 1860.25 For example, compare the smaller arrowhead sizes in Figure 29, recovered from the Avon bison jump in Montana, to larger arrowheads from after 1850, shown in Figure 26.

Fig. 29. Projectile points recovered from a bison jump near Avon, Montana, between 1930 and 1970. Lithic projectile points are at the right, metal points are at the left. Note the similarities in shape and size between some of the metal and stone arrowheads. None of the metal points in this display resemble the so-called trade points found on many mid- to late nineteenth-century Plains arrows. Preston Miller, Four Winds Trading Post Collection, St. Ignatius, Montana. Photograph by Roland Bohr.

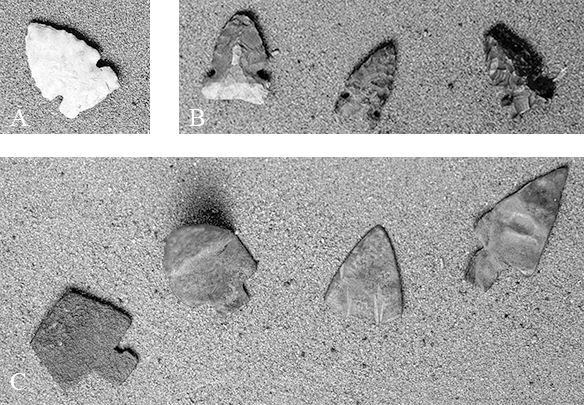

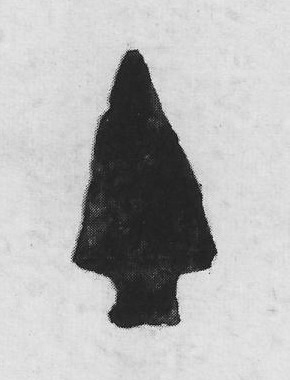

Fig. 30. Stone (A, B) and metal (C) arrowheads recovered from the Morkin site, near Claresholm, Alberta. They date back to ca. 250 years ago. Note the similarity in shape between the stone points in A and B and the metal points in C. Images courtesy of the Royal Alberta Museum, Edmonton.

Fig. 31. Small, heavily corroded iron projectile point from a possible early nineteenth-century Cree burial at Elk Point, Alberta. This projectile point is almost identical to the triangular stemmed points from Fort George. Image courtesy of the Royal Alberta Museum, Edmonton Point (F10r-1/24).

Fig. 32. Intermediate-size metal arrowheads recovered from the Pine Fort site, Manitoba. A: Pine Fort DkLt-1 9188. B: Pine Fort DkLt-1 7185. C: Pine Fort DkLt-1 8447. D: Pine Fort DkLt-1 8485. Total length: 30 mm. Pine Fort was a North West Company post in south-central Manitoba on the Assiniboine River, northwest of modern Brandon, Manitoba. With interruptions, it operated from 1768 to 1811. Images courtesy of the Manitoba Museum, Winnipeg. Photographs by Amber Zimmerman-Flett.

Plains peoples employed a wide variety of arrow points for different hunting or combat situations. Arrows with triangular points were used for big game hunting and combat. Most well known are those of lithic materials, such as flint or obsidian (a volcanic glass). However, Aboriginal people also made triangular arrowheads from broken glass vessels, wood, rawhide, and sinew. Native copper was used to some extent to make arrowheads in eastern coastal North America and in the eastern Great Lakes area. Aboriginal people there made pressure-flaking tools from native copper for the manufacture of stone arrowheads.26

David Thompson’s account of the eighteenth-century Cree/Pikani elder Saukamappee did not describe the arrows used by his people or by their “Snake Indian” (Shoshone) adversaries in great detail, except for the materials from which arrowheads were manufactured. He described the arrows of the Cree, Pikani, and Assiniboine as having mostly stone points. Furthermore, according to Thompson, in Saukamappee’s first battle, when he was sixteen years old, roughly only a fifth of the Cree arrows had metal arrowheads. By the time he fought in his second major battle against the Snake (Shoshone and allies), when he was in his twenties, the number of metal arrowheads used by the Cree had increased. Thompson’s rendering of Saukamappee’s account did not describe the shape of the arrowheads. However, concerning the Snake arrows, he related that “they were all headed with a sharp, smooth, black stone which broke when it struck anything.”27

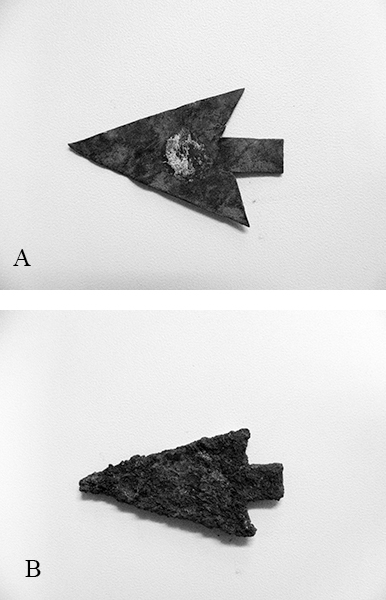

Fig. 33. Barbed metal arrowheads from Pine Fort, Manitoba. A: Pine Fort DkLt-1 7186. B: Pine Fort DkLt-1 8387. Images courtesy of the Manitoba Museum, Winnipeg. Photographs by Amber Zimmerman-Flett.

Fig. 34. Projectile points and other artefacts recovered from Writing-on-Stone, Alberta, including two metal projectile points (I and J). These metal points are closer in shape to late nineteenth-century “trade points” but are still of relatively small size. They do not resemble the late prehistoric proto- contact lithic projectile points A, G, and H, which date approximately to AD 1500. Image courtesy of the Archaeological Survey of Alberta.

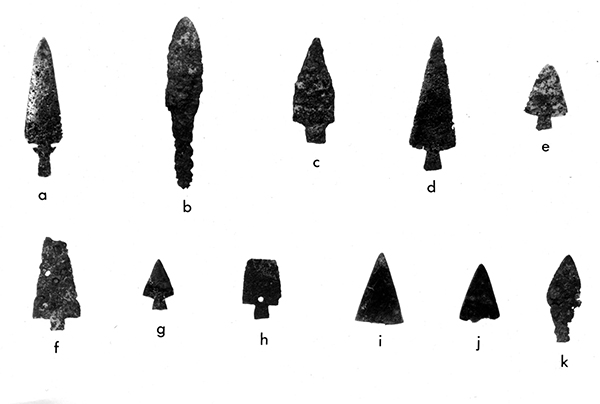

Fig. 35. Metal arrowheads excavated at Fort George, Alberta. The longest point (B) is 7.8 cm long. Note the similarity of the brass point G and the iron point E to lithic arrowheads from the protocontact period. Fort George was a North West Company post in what is now eastern Alberta, adjacent to the Hudson’s Bay Company’s Buckingham House. It was used from 1792 to 1800. Courtesy of the Royal Alberta Museum.

Richard Glover suggested in his edition of Thompson’s narrative that the stone the Snake Indians made their arrowheads from was flint.28 Nevertheless, the qualities and the black color of this stone that Saukamappee pointed out, likely contrasting it to the variety of stone used by the Cree, Assiniboine, and Pikani, suggest that it was obsidian, a volcanic glass common in the Rocky Mountains of what is now Wyoming and Idaho. The Eastern Shoshone used such stone points into the late 1850s.29

George Bird Grinnell stated, regarding the Cheyenne, that the range and penetrative force of their arrows were greatly enhanced by the use of metal arrowheads, to a degree that could not have been achieved with arrowheads made from bone or from lithic materials.30 When brass and iron became available through European traders, these new materials found favor, and in the Plains, flat, oblong-triangular metal arrowheads eventually replaced stone points. The cutting edges of well-made stone points, especially those made from obsidian, were much sharper than those of metal arrowheads, but they did not keep their edge as long, were more difficult to resharpen, and were so brittle that they often shattered upon impact on a hard target, as Saukamappee noted.31 David Thompson related that Saukamappee had told him that metal arrowheads used by the Pikani and Cree stuck in their opponents’ rawhide shields but could not pierce them.32 Stone arrowheads remained in use, at least among some Plains groups, well into the nineteenth century. Henry Wolf Chief, born in 1849, told Gilbert L. Wilson in 1911 that the Hidatsa still used stone points when his father was young.33

Fig. 36. Arrow components (top to bottom): A: Disassembled components of a foreshafted arrow, consisting of a stone projectile point, wooden foreshaft, main shaft made from reed, separate hardwood piece for the nock, and fletching feathers. B: The same arrow shown in A, assembled. C: Parts of a “typical” mid-nineteenth-century Plains arrow: metal projectile point, one-piece solid hardwood shaft, and fletching feathers. D: The same arrow shown in C, assembled. Drawings by Roland Bohr.

Based on a comparison of lithic projectile points with surviving postcontact arrows from the Blood (Kainai), the archaeologist Heinz W. Pyszczyk suggested that arrows with large metal points, attached directly to a solid wooden shaft, came to replace arrows with stone points attached to a wooden foreshaft fitted into a main shaft of reed, such as were found at the Mummy Cave site in Wyoming, dating to ca. AD 730.34

If stone points fracture upon impact, they may splinter the shaft in the process. The use of a foreshaft made it possible to reuse the main shaft, even if point and foreshaft were destroyed or damaged. Metal points, in contrast, were more durable and were less likely to splinter the main shaft. Their greater weight may have made it necessary to dispense with the foreshaft to save weight in order to retain the arrow’s flight characteristics.35 Aboriginal people may have switched from foreshafted arrows to solid shafted arrows to maintain the same arrow weight and performance characteristics because metal points may on average have been heavier than stone points. Weight had to be saved to maintain their flight characteristics. That could be accomplished by omitting the wooden foreshaft.36

This factor may also explain the initially smaller size of early metal arrowheads and their similarity in shape to lithic projectile points, if indeed these metal projectile points were attached to foreshafts, similar to the method of assembly of the arrows found at the Mummy Cave site in Wyoming.

When European fur traders recognized the demand for metal arrowheads, they began to sell them at their trading posts. However, documentary evidence for the gradual displacement of lithic arrowheads by iron and steel points is contradictory. As early as 1670 the Hudson’s Bay Company’s trade goods included arrowheads.37 The York Factory account books list 345 arrowheads shipped from England for the year 1688 and 343 for the year 1689. In 1690 the number in stock fell to 156. As of 1693, there were 126 arrowheads remaining at the post, indicating that over the course of five years, only 219 arrowheads had been traded.38 Even when the company lowered the price per arrowhead by 50 percent, local Native people did not buy the remainder.39

At Albany in 1695, 298 arrowheads were in stock, to be traded at 12 per beaver skin.40 Only 118 arrowheads had been traded by the closing of the accounts for 1695. At the same time, the trade volume in firearms, ammunition, and gun accoutrements at that post included 11,653 pounds of shot, 4,956 pounds of powder, 5,555 flints, 396 guns of 4.5 and 3.5 foot length, 272 gun worms, and 201 powder horns.41 After 1693, no arrowheads appeared in the York Factory account books until 1759–60, although sales figures for firearms and ammunition remained consistent. Arrowheads received at the bayside posts in the second half of the 1700s could not be sold locally either. This may indicate that either these arrowheads were not of the quality or design that the Lowland Cree preferred, or that archery, beginning in the late 1600s, had been gradually losing its predominant role in big game hunting and combat.

In 1759–60 York Factory received 390 metal arrowheads from Richmond Post on the east coast of James Bay because they could not be sold there.42 The next listing of arrowheads was for 1786, when York Factory received 1,200 arrowheads from England. In 1792 this number had increased to 3,456. For 1793, the inventory included 3,168, and for 1794, 2,592 arrowheads.43 By 1796 some 2,160 arrowheads were left. The accounts for that year include a note stating that these English arrowheads could not be traded, as Native people would not buy them. This same number of arrowheads remained unchanged in the inventory until 1799, but by 1801 the number had decreased to 1,728.44 In contrast, the trade list inventory of the HBC’s Buckingham House indicates that from 288 to 720 “arrow barbs” were sent inland each year from 1791 to 1795.45 A letter from HBC post manager William Tomison at Hudson House to William Walker, from September 22, 1788, indicates among the unsold trade goods that Tomison sent to Cumberland House were “200 arrow barbs.”46 On January 27, 1791, “the Sussew and Southward Indians arrived, seven of these I was obliged to rig.” Tomison gave them presents, although he was low on goods. He gave “[each of?] them an arrow barb to cut their Tobacco with.”47

It may be that arrowheads manufactured in Europe proved more difficult to sell than those made by local blacksmiths at the trading posts frequented by Native customers. For example, in 1706 at Albany, 146 arrowheads were “made and fitted here in the Factory by the governor his order the following particulars [sic].”48 In 1814 Alexander Henry the Younger observed about the Chinook leader Comcomly on the West Coast: “[He] came in with a long piece of bar iron to get made up into arrows points &c by our blacksmith, but as we find him rather troublesome and a great beggar. We conceive it necessary to give him to understand that we are not bound to have so much work done for him as heretofore has been the case here. Trifling jobs we are always ready to have done for him, but not to work up whole bars of iron.”49

While blacksmiths at different trading posts may have manufactured arrowheads for Aboriginal customers, these were probably not very uniform, because each post’s blacksmith likely had his particular style. Furthermore, although there is at present no evidence for this, it is possible that Aboriginal customers provided manufacturing directions for the shape and size of the arrowhead patterns they wanted, thus individualizing the product even more.

Hudson’s Bay Company records indicate that as early as the late 1600s, arrowheads imported from Europe were difficult to sell in posts along the shores of Hudson and James Bays, either because local Aboriginal archers preferred to make and use their own or had already switched from bows and arrows to firearms as their main distance weapon for big game hunting and combat. The consistent sales of firearms, ammunition, and firearms accessories, compared to the relatively low sales figures for imported arrowheads, seem to indicate a growing reliance on firearms by Native people in the Hudson Bay Lowlands and adjacent Subarctic regions. By the late 1700s, when the Hudson’s Bay Company and its Montreal-based competitors established permanent posts in the Plains, the sales of metal arrowheads increased, likely because Plains peoples preferred the bow and arrow over muzzle-loading firearms for bison hunting from horseback, thus creating a demand for these projectiles. This is supported by the fact that by the 1830s, arrowheads were even mass-produced in the United States specifically for the “Indian trade.”50 George Catlin observed in 1832 that American traders on the Upper Missouri commonly sold metal arrowheads to the Blackfoot, Crow, and other Northern Plains peoples.51 The Crow leader Plenty Coups related to Frank Linderman in the 1930s: “When I was seven, my arrows had good iron points which my father got from the trader on Elk River. This trader’s name was Lumpy-neck.”52

However, as with metal arrowheads recovered in archaeological contexts, it is difficult to distinguish between surviving metal arrowheads of European or U.S. manufacture and those of Aboriginal manufacture. Some commercial manufacturers marked their arrowheads.53 Some arrowheads with wide holes drilled through them may represent trade points because these holes made it possible to string the arrowheads on a cord in dozens, for instance, for easier shipping and trading.54

In his 1999 collector’s guide to Native American archery artefacts, John Baldwin presented a photograph of nine metal arrowheads from a private collection. It bears the following caption: “Nine arrow points of iron. The seven smaller points were [until] recently packed together in an original Hudson’s Bay Trading Company’s wax paper wrapped packet of 50 points. Their non-studied owner unknowingly unwrapped them and discarded the paper. These points represent typical Indian trade points.”55

These seven arrowheads display a very distinct shape that is consistent with some rare metal arrowhead shapes used by Northern Plains peoples. They are triangular, with a tang for attachment to the arrow shaft protruding from the base of the triangular blade. The base of the blade is straight and rather wide. The tips of the blades are pointed, not rounded, and the cutting edges of the blades are rather narrow. In four of these seven arrowheads the ratio of base width to blade length is 1:2.5. In contrast, most nineteenth-century Plains Indian metal arrowheads I have examined have slightly rounded tips and fairly wide cutting edges on their blades.56 Their ratios between base width and blade length are at least 1:4, often reaching even 1:6. While the alleged Hudson’s Bay Company trade points described by Baldwin were short and wide, mid- to late nineteenth-century Plains Indian metal arrowheads were commonly narrow and long.

Arrows with metal arrowheads similar to the alleged HBC trade points were collected in the early to mid-1900s from the Blood in south-central Alberta, Stoney in southwestern Alberta, and Hidatsa in central North Dakota.57 These peoples either traded directly at Hudson’s Bay Company posts or were within reach of Aboriginal middlemen who traded with the HBC. However, arrowheads like the ones illustrated by Baldwin are rarely encountered on arrows in museum or private collections. Commenting on two of these arrows now at the Glenbow Museum in Calgary, Siksika elder Clifford Crane Bear stated that these arrowheads were far too wide at the base to penetrate well, their proportions resembling those of a shovel more than an arrowhead.

Metal arrowheads with a diamond shape were easier to withdraw from a wound than arrowheads with a straight and wide base, or with barbs; thus the diamond-shaped ones were ideal for hunting (see Fig. 26B). Unlike barbed arrowheads, diamond-shaped arrowheads did not cause excessive damage to the animal skin when withdrawn, and they remained attached to the arrow shaft and thus could easily be used again in another hunt. In contrast, arrowheads meant for war often had barbs to make withdrawal of the arrowhead difficult or impossible.58 Such arrowheads were only lightly wrapped to their arrow shafts with a few turns of sinew. When they entered an opponent’s body, the blood softened the sinew and the arrowhead would detach and remain in the wound when the shaft was withdrawn (see Fig. 26A).59

A common misconception about North American Aboriginal arrows is that arrowheads meant for hunting were attached parallel to the notch for the bowstring at right angles to the ground, so that they would pass between the ribs of a standing animal. By the same reasoning, arrowheads meant for fighting were supposedly attached at right angles to the string notch, horizontal to the ground, so they would pass between the ribs of a standing human.60 However, regardless of the type of arrowhead or fletching used, an arrow spins in flight. While advantageous and necessary to stabilize the arrow, this spinning in flight also makes it impossible to predict at which angle the arrowhead will strike its target.61 It is very unlikely that Aboriginal arrow makers believed that they had to mount metal arrowheads meant for war differently from those meant for big game hunting, because through extensive practice, they were aware of the unpredictability of the arrowhead’s impact angle. Clark Wissler noted that none of his Blackfoot informants seemed to have heard of such a distinction.62 However, shooting experiments with reproductions of Plains arrows with long fletchings, which I conducted along with the bow maker and horse archer Jay Red Hawk of Box Elder, South Dakota, in the summer of 2012, showed that such arrows spin much less in flight than arrows with shorter fletchings.

The Plains arrows examined for this study showed little consistency in the placement of metal arrowheads. They were inserted into the shafts at almost any angle, but that angle usually varied from the angle of the string notch. Placing the arrowhead at a different angle from the string notch made the shaft less likely to split upon impact.

Most of the Plains arrowheads I examined did not have a diamond shape, nor did they have pronounced barbs. They were of an “all-purpose” type: flat, with an oblong and triangular shape, and a straight or slightly forward-slanted base of the blade. Such arrowheads were equally suited for hunting and combat (see Fig. 26C). This type seems to have become common during the nineteenth century. Most of these metal arrowheads from the Northern Plains were from 6 to 10 centimeters (2.5 to 4 inches) long and from 1 to 2 millimeters (ca. 1/16 inch) thick.63 Southern Plains metal arrowheads were mostly shorter, narrower, and lighter, that is, of a more delicate shape, to reduce weight. This may have been necessary because the slightly longer bows of the Southern Plains required longer arrow shafts than those used in the Northern Plains.

Northern Plains people also employed several types of arrows with club-shaped, bulbous heads for killing small game and birds. Such arrows were mostly made from a fairly large, thick branch or shoot of the same diameter as the desired pear-shaped or bulbous arrowhead. The rest of the shaft was then reduced to its final diameter.64

Arrows with their shafts whittled to a point were used in target practice, to kill rabbits or fish, and sometimes also in combat.

Wolf Chief stated that he never heard about or saw arrowheads of bone in use among the Hidatsa. However, his coworker Gilbert Wilson noted that bone and horn arrowheads had been found in refuse heaps at old Mandan and Hidatsa village sites near Mandan, North Dakota. Wolf Chief and his sister Buffalo Bird Woman stated that sometimes the Hidatsa made arrowheads from bison horn.65

From his father, Small Ankle, Wolf Chief learned that in the past the Hidatsa made arrowheads from the front teeth of beavers. The teeth were boiled in water for a long time until they were somewhat flexible. Then they were pressed flat with a heavy stone until dry. This procedure was repeated several times to completely flatten and straighten the beaver teeth. Because they were already extremely sharp, they did not need an extra edge. According to Wolf Chief, such arrowheads had great penetrative force. Because the cutting edge of a beaver tooth is straight and the tooth is more rectangular than triangular, I assume that such arrowheads were mounted with their cutting edge at a right angle to the shaft, similar to the chisel-shaped stone arrowheads used by Neolithic peoples in western Europe. Recent shooting experiments with the latter showed that they had great penetrative capability.66 However, so far no actual examples have been found in North America. Such beaver- tooth arrowheads may have been in use in other areas outside the Plains where beaver were more abundant.

Plains Fletchings

Radial fletchings, made from three large bird feathers with their quills split and flattened and attached equidistant to each other on the arrow shaft, were most common in the Plains. The front and rear ends of the feathers were bound to the shaft with sinew. On most of the examined Plains arrows the feathers were also glued to the shaft with hide glue. A few arrows had the front and rear parts of the quills of their feathers only wrapped to the shaft but not glued. This technique seems to have been especially prevalent among Cheyenne and Blackfoot-speaking peoples.67 Attaching the fletching feathers without glue and only with wrappings of sinew does allow for easier realignment of the feathers or the quick exchange of damaged feathers. However, without glue, the individual feathers will eventually work themselves loose under the constant strain of shooting and handling the arrow, especially since the sinew was not threaded between the vanes of the feathers in a long spiral along the shaft, but was wrapped around only the front and rear protrusion of the quills. The tradeoff might thus have been between sturdier construction of fletchings attached with glue and greater ease of maintenance of those attached without glue.

Plains fletchings were very long, between 15 and 22 centimeters (ca. 6 to 8.5 inches), and the vanes of the feathers were trimmed rather low, between 5 and 9 millimeters (ca. 3/16 to 3/8 inch). When feathers were in short supply, sometimes only two instead of three split feathers were used. However, in my experience such arrows stabilize less well and are more difficult to aim accurately than those with three split feathers.

Most of the Plains arrows I examined had three split feathers placed on the shaft equidistant from each other in what is known as a “cock feather” arrangement. In this type of fletching, one feather, referred to as the cock feather, is set at right angles to the nock for the bowstring. The remaining two feathers are each placed equidistant from the first. Arrows with this feather arrangement must be nocked with the cock feather pointing outward, away from the bow, so that the arrow clears the bow handle with less resistance. If the arrow is nocked and released with the cock feather toward the bow, the feather could scrape against the handle and be damaged as it passes the grip.

Fig. 37. Bird-hunting arrow, in which thorns or crosspieces are lashed to the front end of the main shaft. The use of variants of this kind of arrowhead has been documented for Hidatsa, Navajo and Inuit peoples. Reproduction arrow manufactured by Roland Bohr. Drawing by Margaret Anne Lindsay.

Another type of fletching consisted of a very long single split feather, with its quill attached to the shaft in a long spiral. Arrows with such fletchings could be used for shooting upward, for instance at birds taking flight or at squirrels in trees. The spiral fletching allows a powerful but rather short flight and then abruptly stops the arrow, preventing it from going too far. A bird-hunting variety of these arrows often had three or more large thorns attached equidistant from each other about 10 to 15 centimeters (ca. 4 to 6 inches) from the sharpened tip of the arrow. An arrow with such protrusions could bring down two or three small birds with one shot when shot into a flock of birds.68 Aboriginal people in the Subarctic, Northern Plains, and Southwest made and used such arrows.69 Equipped with triangular metal points, spirally fletched arrows were occasionally also used in battle, at least by the Hidatsa.70

With the increasing availability of metal arrowheads, the rich diversity of Aboriginal arrowheads in the Northern Plains began to diminish. Making arrowheads from native materials such as stone, bone, or wood was time-consuming and labor-intensive, while metal arrowheads could often be obtained readymade at the trading posts. Metal arrowheads were of sufficient quality to accomplish most of the tasks traditional arrowheads had been used for, and they were more convenient and often more durable than arrowheads of stone or bone. However, while arrowhead technology changed, the bow and arrow remained in use in big game hunting and combat in the Plains well into the 1870s.

Arrows of the Central Subarctic

According to Louis Bird, the Omushkego-Cree made arrow shafts either from willow shoots or from split coniferous wood, such as black spruce. None of the archery collections I examined held Subarctic arrows made from natural shoots. Rather, all Subarctic arrows I examined were made from split wood.

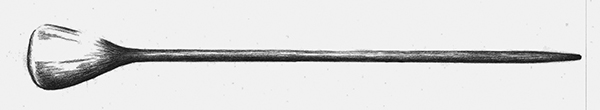

Most surviving Subarctic arrows are so-called bird blunts. They have very large pear-shaped arrowheads used to kill small mammals or to disable larger birds such as geese. These arrows look massive but are actually quite lightweight. In order to build up enough critical mass to cause sufficient damage to the target, they need to be quite big, because the wood they are made of becomes very light once it dries.

Louis Bird also mentioned that wide arrow points of sharpened bone were used to hunt big game such as moose and caribou. Four such arrows at the Manitoba Museum in Winnipeg, made from split coniferous wood and collected from the Granite Lake Cree in central Saskatchewan, are equipped with such points.71 The shafts of these arrows varied in length from 62 to 66.5 centimeters (ca. 24.5 to 26 inches). All four arrows are equipped with large points of a triangular or diamond shape, made from large, thick, flat bones. These massive points are up to 8.5 centimeters (ca. 3.4 inches) long, 4.2 centimeters (1.65 inches) wide, and are around 7 millimeters (0.27 inch) thick.72 Only one of these arrows has fletchings, made from three split feathers wrapped to the shaft in a radial arrangement with a fine white commercial thread.73 The quills are not glued to the shaft. The other three arrows do not have any fletchings at all.

The nock ends of these arrows have been flattened and the notches for the strings are wide and deep, a feature also found on arrows from the Northwest Coast, from Inuit, and from other Aboriginal peoples from northern boreal forest environments, such as the Naskapi and Montagnais.74 The flattening of the nocks facilitates the use of a Mediterranean-style arrow release, especially when a shooting glove of some sort is used. Louis Bird mentioned the use of a shooting glove, and in demonstrating the kind of arrow release most common among the Omushkego-Cree, he indicated that the bow string was pulled back with the index and middle fingers only. The index finger was placed above and the middle finger below the arrow nock. This kind of arrow release is a variation of what is often referred to as the Mediterranean arrow release (see Fig. 28A and 28B).75

Fig. 38. Subarctic blunt-headed arrow from central Manitoba (University of Winnipeg, Anthropology Collection E5–294). Subarctic people sometimes flattened the nocks of their arrows to make it easier to use a shooting glove in combination with the Mediterranean arrow release. Drawing by Margaret Anne Lindsay.

Fig. 39. Subarctic shooting glove. Subarctic peoples, for example the Naskapi, occasionally used a shooting glove made from brain-tanned leather. Drawing by Margaret Anne Lindsay, based on an artefact collected by Frank Speck from the Naskapi in the 1930s, now at the University of Pennsylvania Museum, Philadelphia.

Fig. 40. Possible metal arrowheads recovered from northern Manitoba. A: Churchill River HiLp-1 10361. B: Nelson River GjLp-14–3. Note similarity to arrowhead in James Isham’s drawing in Figure 22. However, these flat pieces of metal may not have been projectile points at all, but may have been intended to be rolled into tinkling cones. Photographs by Amber Zimmerman-Flett, courtesy of the Manitoba Museum, Winnipeg.

Fig. 41. Possible Subarctic arrow (cat. no. H76.100.136–138 Royal Alberta Museum) with stone point. Maximum length of this point is ca. 25 millimeters. Note the similar shape of this arrowhead compared to the artefacts in Figures 22 and 40A,-B. Courtesy of the Royal Alberta Museum, Ethnology Program, Edmonton. Photograph by Ruth McConnell.

A set of blunt-headed, club-shaped arrows for hunting small mammals and birds is representative of this type of arrow, which is frequently found in the Subarctic. This set from the Nelson House Cree consists of four arrows and was collected with two self bows.76 The overall length of the arrows ranges from 41 to 52 centimeters (16.14 to 20.47 inches). The short draw length suggests that they were not made for an adult archer. They were made from split coniferous wood. The arrowheads are all round in cross section. Their diameter is about 2.7 centimeters (1.063 inch) at the front end of the club, which then gradually blends into the arrow shaft itself. The massive shafts range in diameter from 1 to 1.15 centimeters (0.39 to 0.45 inch) at their center. The nock ends are of the same diameter as the shaft, neither raised nor flattened.

Such bird blunts can fly straight without any fletchings at the back end. The heavy arrowhead already provides enough weight at the front end and thus enough steerage to make the arrow fly straight, at least for short distances. The same might apply to the previously discussed Subarctic arrows with massive bone arrowheads. Even though James Isham recorded the use of bladed metal arrowheads among the Lowland Cree in the mid-eighteenth century, none of the Subarctic arrows I examined was equipped with a bladed metal arrowhead of any kind.77

Metal arrowheads recovered from archaeological sites on the Churchill and Nelson Rivers in Manitoba display a wide range of shapes, from lanceolate with tangs to large equal-sided triangles without any tang for attachment to the arrow shaft.78 These latter arrowheads are rather similar to those drawn by James Isham, published in his 1743 Observations on Hudson’s Bay (compare Fig. 22).79

If these pieces of metal were indeed arrowheads, it is not clear how they could have been hafted efficiently. However, a Subarctic arrow now at the Royal Alberta Museum in Edmonton is still equipped with a stone projectile point of similar shape (see Fig. 41).

Louis Bird mentioned distinct coastal Cree terms for arrows with bone, stone, or metal points: oshkan akask (bone arrow for big game), assiniwakask (arrow with stone), piwaapisko akask (arrow with a steel head), piwaabiskostekwan akask (arrowhead and part of the shaft made out of steel, for shooting fish).80

Bowyers and Arrow Makers

Because arrow making required extensive skill and took years to learn, one might wonder if all Aboriginal archers made their own equipment or if specialists performed this task.81 Ethnographic evidence and historic documents offer contradictory information on the existence of specialized makers of archery gear in Plains societies. While some sources indicate that Aboriginal archers usually made their own equipment, others state that specialists crafted most archery gear. Reliance on specialists may have been more prevalent among peoples with age-graded societies, such as the sedentary and agricultural Mandan and Hidatsa of the Upper Missouri River and the mobile, bison-hunting Blackfoot of the Northern Plains.

Closer examination may serve to refine these generalizations. When anthropology emerged as a scholarly discipline during the late nineteenth century, researchers assumed that in so-called primitive cultures the user of an object usually also was its maker.82 Specialization was seen as a trait of proto-industrial and industrial societies and was assumed to be lacking in “simple” societies of hunters and gatherers. This view, which favored the notion that every Aboriginal man made his own archery equipment, greatly influenced anthropological research at the time.83

Fig. 42. Unusual oblong, lanceolate metal projectile points from Manitoba. A: Nelson River GlLr-29–24. B: Pine Fort DkLt-1–7185 (bottom). Courtesy of the Manitoba Museum, Winnipeg. Photographs by Amber Zimmerman-Flett.

Fig. 43. Iron arrowhead from the Tailrace Bay excavations in north-central Manitoba. This arrowhead is similar in shape and size to some of those recovered at the Plains post of Pine Fort (see Fig. 32). Total length: 42 millimeters.

At least the basics of bow and arrow manufacture were likely general knowledge among many Aboriginal groups, however. For instance, in interviews with the ethnographer Kenneth Kidd in the 1930s, the Blackfoot Spencer Owl Child stated that boys were commonly taught the basics of arrow manufacture, while old men were able to devote more time to mastering the fine points of this art.84 In the 1860s the Crow Two Leggings made a snakeskin-covered bow from hickory wood he had traded from a group of Gros Ventre des Prairies. He also made a matching set of arrows from chokecherry saplings for this bow. However, Two Leggings did not consider himself to be a specialist in the manufacture of archery gear. He was orphaned early in life and raised by his older brother. Lacking influential relatives, they lived on the margins of Crow society. Making an archery outfit was part of Two Leggings’ quest for military honors and prestige in order to rise among his people. He stated that for him, making this archery set was mainly a meaningful pursuit to fill the long and empty winter months, assembling weapons that could be helpful in increasing his warrior status in the future.85

A hunter or warrior had to be able to manufacture basic archery equipment in order to quickly replace a bow or arrows lost on a hunt or while traveling. Such emergency scenarios and how to deal with them were part of Aboriginal peoples’ stories and legends. Resourcefulness, self-sufficiency, and independence were considered important attributes in Aboriginal cultures, where men were expected to fulfill the roles of provider and protector of their families. For instance, the Crow legend of “Bear White Child” mentions an orphaned boy who, not unlike Two Leggings, made his own archery set while traveling on a long journey. The deer the boy killed with these weapons provided him with food during his entire journey.86

U.S. Army officer William Philo Clark commented on the resourcefulness of Aboriginal men in the Northern Plains. During the closing decades of the nineteenth century Clark was part of a scout unit, working mostly with Northern Cheyenne men. While traveling, they found it necessary to have a bow. Within a few hours, using only their heavy hunting knives, Clark’s Aboriginal companions made a perfectly serviceable self bow from a broken ash wagon bow.87

Among some Aboriginal groups, women also held knowledge pertaining to the manufacture of archery gear. According to Cheyenne traditions, a woman initiated the use of sinew bowstrings. Before the Cheyenne moved into the Plains they used bowstrings made from plant fiber. However, these were not sturdy and did not last long.88 While butchering bison after one of the first hunts in the Plains, a woman noted the long and wide sinews running parallel to the animal’s spine from head to hip. She mentioned to her husband that these sinews might make better bowstrings, and from then on the Cheyenne were said to have used sinew bowstrings.89

Among the Subarctic Omushkego-Cree, women were generally not supposed to use or even touch a war bow and its arrows.90 However, many Omushkego-Cree men preferred their wives or daughters to attach the fletchings to their arrows, because women were considered more skillful at such delicate work than men. As Louis Bird related,

The women were good at that [applying the fletching], because they can make string with the sinew from the animals, sometimes just the beavers and the otters sometimes make a fine, fine sinew. And that’s what they used to wrap around these feathers and so they won’t hurt on the hand, the finger of the man, in here [Louis Bird indicated the right side of the left index finger between the knuckle and the middle joint where the arrow would slide across during discharge. Smoothing the wrapping of the arrow shaft was important because any protrusion or rough spot could cause severe cuts to the hand.] They were good at that. So the women usually used to make that. But the men would put the head, if there is a big game animal. And if it’s a goose they had just a little sharp thing, very easy to go through. And sometimes they got the big head, just to knock it down.91

Some Omushkego-Cree men, in contrast to their sensitivity about war bows and arrows, liked to have their wives or daughters touch their hunting bow and arrows before they set out to hunt, because they believed this would bring them luck.92

The Blackfoot Joe Little Chief, who in the 1950s collected oral traditions and accounts of his community’s history, stated that in the past among his people, “[the women] also learn how to shoot with bow and arrows some are very good at it.”93 Hugh Munroe, a former employee of the HBC who had married a Piegan woman and lived with the Piegan beginning in 1823, stated in 1886 that he knew a Crow woman, the wife of the American trapper Jim Beckwourth, who had used lance, tomahawk, and bows and arrows in combat. She was said to have gone on war parties and killed many enemies.94

Henry Wolf Chief’s sister Buffalo Bird Woman (Hidatsa) made a toy archery set for her young son Goodbird. She mentioned that Hidatsa mothers commonly made such toy archery sets for boys.95 Goodbird said that with this equipment he hunted mice and other small rodents within his family’s earth lodge when he was about four years old, but he never killed any animals because they were too fast for him.96

Among the Hidatsa, women were commonly not allowed to make and use adult archery gear. However, the fact that Buffalo Bird Woman and other Hidatsa women manufactured fully functional toy bows and arrows shows that they had at least a working knowledge of the basic principles of bow and arrow manufacture. Buffalo Bird Woman also gave detailed information on various aspects of the manufacture of bows and arrows intended for big game hunting and combat. If such knowledge was commonplace among the women, the average Hidatsa man surely had even greater knowledge of the manufacture of archery equipment, because men in Plains Aboriginal cultures were involved in archery-related matters on an almost daily basis. For example, in February 1793 Peter Fidler observed while among the Pikani, “the men all also busily employed making arrows—of the Sascuttem wood, which is very hard & solid when dry—there is great plenty of it here along the river.”97 The anthropologist Alfred W. Bowers confirmed this pattern for the Mandan, stating that it was common for every adult Mandan male to manufacture arrows.98

On the other hand, some sources report the existence of highly specialized bow and arrow makers among Aboriginal peoples. Ojibwa traditions indicate that at least among the south-central Ojibwa, and possibly among other Algonquians, there was a particular class of men, before the introduction of firearms, called “makers of arrowheads.”99

Several Cheyenne mentioned to George Bird Grinnell that the father of a man named Shell was a highly qualified arrow maker.100 Shell’s family was wealthy and well respected, partly because Shell’s father made high-quality arrows for other warriors who paid him for his work. As a boy, Wolf Chief owned very good arrows, which his father, Small Ankle, had made for him. As the son of an arrow maker he was always supplied with first-rate arrows.101 Wolf Chief later became an accomplished arrow maker himself, possibly after formally entering into an apprenticeship with his father.102

Mandan and Hidatsa society was ranked and based on the formal recognition of seniority and experience. The transfer of knowledge was highly restricted and followed a precise protocol, established deep in the past. Knowledge and skills were divided into ordinary and ancient or sacred. Quillwork embroidery, the manufacture of ceramics, and the catching of eagles were all considered “ancient” knowledge. No one was allowed to acquire these skills simply by imitating more experienced people. A potential candidate, in order to acquire the right to learn and practice a certain craft, had to formally approach a master craftsman or craftswoman and enter into a formal apprenticeship. Throughout their training, apprentices were expected to make valuable gifts to their mentors as payment for knowledge gained. In exchange, they could eventually take over the positions of their mentors when the training was complete.103

Among the Mandan and Hidatsa, the knowledge and skills to make sinew-backed sheep horn or elk antler bows were evidently restricted and had to be acquired in a formal apprenticeship; the making of simpler self bows, however, was not restricted. Several Mandan claimed to the anthropologist Alfred W. Bowers in the 1930s and 1940s that the right to make arrows was also restricted and was connected to the acquisition and possession of certain sacred bundles. Such bundles could originate with instructions received from a spirit being encountered in a dream or vision. To secure the help of this spirit guide, the recipient would manufacture a sacred bundle, containing items seen in the vision. Through a transfer ceremony, the powers inherent in the bundle, as well as the right to perform activities related to it, could be bestowed on another person. Subsequent owners of the same bundle might add to its contents, and over time the value and prestige accorded to the bundle by the community would grow. In this way, sacred bundles were not just objects of spiritual power but became repositories of knowledge and social prestige. According to some Mandan, only the owners of these bundles and those who had purchased some of the rights and privileges that went with them were allowed to make arrows, so that only a few expert arrow makers among the Mandan supplied all other people with their products at a price. Bowers was told that unauthorized persons were not even allowed to watch the arrow makers at work.104

The Snow Owl bundle of the Mandan, for instance, contained arrow-making tools such as a multipurpose tool for straightening and grooving arrows, made from a bison rib. There were also wooden blocks having a straight groove of half-rounded cross section to hold a piece of leather with sand glued to one side, used to reduce the arrow shafts to their proper diameter (Aboriginal sand paper).105 The Snow Owl myth tells of the mythic character Black Wolf, who received arrow-making tools as payment for services rendered to an arrow maker.106

The Eagle-Trapping, Big Bird, and Woman-Above bundles also incorporated arrow-making rights, all associated with birds of prey. The Big Bird bundle was associated with spiritual beings referred to as “Thunderbirds.”107 The presence of arrow-making tools and the association between arrow making and sacred bundles lend credence to the idea that arrow making was restricted among the Mandan.

At least some Blackfoot groups may have exhibited similar patterns. Blackfoot-speaking communities, past and present, had an age-graded society system like the Mandan and Hidatsa, and their spiritual activities revolved around sacred bundles and the rights to specific knowledge that came with their purchase. According to the Peigan elder Jerry Potts, the Blackfoot acquired many aspects of their spirituality from the Mandan and Hidatsa, and each group had influenced the other.108 However, the Blackfoot Joe Little Chief recorded that while knowledge about the manufacture of bows and arrows involved specialized skills, it was widely shared by those who knew: “They [Blackfoot boys] learn how to make bow and arrows there is a man that teaches the flint heads for the arrows how to make them when they know how to make them what kind of green sticks to use then they learn how to shoot with Bow and arrows they go with a man that teaches them how to shoot with the Bow and Arrows they then have to make the Bow and Arrows and keep them at their tepees and they can hunt.”109

Joe Little Chief related that his great-grandfather’s name had been A-no-wa, “Making Arrows,” because he used to go through the camp of his band to tell the people to keep making arrows every day.110 This again implies that there were few if any restrictions on the manufacture of bows and arrows, and Blackfoot men commonly learned how to make their own archery gear when they were still boys. However, they acquired this knowledge from specialists.

Similarly, Wolf Chief and other Mandan and Hidatsa working with Gilbert Wilson in the 1910s did not mention limitations in arrow making. Wolf Chief clearly indicated that although there were arrow-making specialists among the Mandan and Hidatsa, no man was forbidden to make arrows. This apparent contradiction may be resolved by examining the age of Wilson’s and Bowers’s Aboriginal coworkers. Bowers interviewed people on the Fort Berthold Reservation in North Dakota from the 1930s to the 1950s, several decades after Wilson did his work. These men and women belonged to the last generation who had spent their childhood in Like-a-Fishhook, the last prereservation village of the Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara, which was given up soon after the establishment of the reservation and the enforcement of U.S. land-allotment policies after 1887.

The devastating smallpox epidemic of 1837 forced the few survivors of the Mandan and Hidatsa to leave their separate villages and move into a single village, Like-a-Fishhook, in 1845. They also faced a steady stream of non-Aboriginal settlers moving into the area and attacks from the more numerous Dakota, Lakota, Assiniboine, and Cheyenne who on occasion waged war on the sedentary and agricultural people of the Upper Missouri.

Many bundle owners, spiritual leaders, and craft specialists died in the epidemics before they could pass on their knowledge to their designated successors. Thus much knowledge was lost, and many traditions were not continued. During their four decades at Like-a-Fishhook, people from different Aboriginal groups also had to organize and regroup into a single community and political entity, which was further complicated when the surviving Arikara joined the village in 1862. The coexistence of three ethnic groups with mutually unintelligible languages, divergent religious concepts, and different political systems, as well as the loss of elders and ceremonialists through epidemic diseases, combined to loosen old concepts and change traditional views.111

In the late 1880s, under the 1887 Dawes, or Allotment, Act, the U.S. government enforced the abandonment of Like-a-Fishhook and settled families on separate farm plots or homesteads, while the “surplus” land was opened to non-Aboriginal settlement. This dispersal of Aboriginal families was intended to foster assimilation through making them learn to value private property, and it aimed to destroy the traditional community and reduce the influence of the bundle owners as spiritual leaders. The heavy-handed enforcement of assimilation policies eventually caused a backlash among the people of Fort Berthold, who began a more or less covert reorientation toward the remnants of their traditional culture.112 It was from this perspective that Bowers’s informants supplied their information in the 1930s and 1940s. Many of their accounts pertained to the first three decades of the nineteenth century, the time before the major smallpox epidemic of 1837. Few if any of them had lived through those times; rather, they passed on information obtained from their elders. Bowers’s Aboriginal consultants at the time he interviewed them were under the pressure of enforced assimilation and the loss of their traditional ways of life and their land, which was soon to be inundated under the waters of Lake Sakakawea and the Garrison Dam. They may well have romanticized and idealized a “golden age” of Mandan and Hidatsa culture from about 1800 to 1837.

In contrast, most of Gilbert Wilson’s consultants belonged to an older generation. Buffalo Bird Woman was born about 1839 and her brother Wolf Chief in 1849; and Black Chest, a Mandan, was approximately the same age as Wolf Chief. In their youth they had experienced the devastation, insecurity, and instability during the aftermath of the smallpox epidemic of 1837 and the early years of Like-a-Fishhook. They all seem to have been pragmatists with little need to idealize their culture and restore its past. In a sudden, cruel, and inexplicable way the smallpox had transformed their world into a chaotic and dangerous place. In order to survive, it was of outmost importance to always be resourceful, alert, and ready to defend against the Lakota and other Plains peoples.

This was one of the reasons Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara men joined U.S. military campaigns against the Lakota, Cheyenne, and Arapaho in the 1860s and 1870s. At this time bows and arrows were still used in combat and for hunting while on campaigns. Therefore, military necessity could have caused the old restrictions on the manufacture of archery gear to become a liability. It is likely that at this time many warriors made their own arrows. A few select specialists may have maintained their activities, even though by then firearms were displacing archery in importance as combat weapons. The majority of the bows and arrows manufactured by Mandan, Hidatsa and Arikara men, while still fully functional, may no longer have been of the same high quality, compared to the time before the epidemic of 1837.

The Pawnee showed a range of patterns in arrow manufacture. According to the anthropologist Gene Weltfish, every Pawnee man made his own arrows, bow, and bowstring. In contrast, among the Skidi-Pawnee there were supposedly only five specialists who made arrows for every man.113 This they allegedly did free of charge to ensure the availability of a high number of first-rate arrows, which was an important contribution to the defense of their village against the seemingly all-powerful Lakota. It also contributed to success in bison hunting and thus to the livelihood and security of the arrow makers and their families.114

The Omaha had specialists not only for making bows and arrows but also for the manufacture of bowstrings.115 Some specialists even focused only on certain steps of arrow manufacture, such as the cutting of grooves into arrow shafts. The Omaha had few if any restrictions on arrow making. Most men made their own arrows. But specialists provided superior archery products that surpassed average workmanship. The Hidatsa Buffalo Bird Woman related: “I remember that there were two men in our village that were very expert in making sinew backed bows. A tanned buffalo skin was the price of one. Such bows were popular.”116

These examples suggest that while most Plains Indian archers had a fair knowledge and ability of bow and arrow manufacture, the making of horn and antler bows or very high quality arrows remained in the hands of specialists. However, younger men who sought to establish their reputation as hunters, warriors, and eventually war leaders may have had little inclination to spend time learning the fine points of arrow making, which could be mastered only after years of training. Older men were thus more likely to devote their time to the manufacture of arrows, because they were no longer very active as war leaders and hunters and had few military obligations.

In the context of the strong warrior ethos prevalent among most Plains Indian peoples throughout the nineteenth century, it was often considered more desirable for a man to die in battle at the height of his power than to become old and feeble and thus a burden to his family.117 However, men who had acquired prestige and recognition in their warrior years may have considered the making of arrows a worthwhile pursuit for their old age. To Aboriginal people, arrows were more than simply ammunition. A well-made arrow could make the difference between a successful hunt and starvation or between survival and death in battle. Such arrows were highly valued. Archers did not simply discard a lost arrow but spent a lot of time searching for it so that they could place it safely back in its quiver.118

Whoever has watched a well-made arrow fly and strike its target will realize upon close inspection that such a projectile is a work of art. Among the Hidatsa, ten well-made matching arrows were worth as much as a horse.119 The Arapaho considered bows, arrows, and quivers valuable wedding presents, often regarding them even more highly than horses.120

Among the Cheyenne, connecting two families through marriage involved reciprocal gift giving. In order to represent the new connection between the families, the groom would present his bride’s younger brother with an archery set. In Cheyenne traditions, arrows often appeared as wedding gifts to young men from the bride’s family.121 Expert craftsmanship and their high price made such arrows symbols of prestige and high status.122 Thus, a young warrior from a leading family, striving for success, might enhance his prestige by obtaining his arrows from a renowned craftsman, rather than making his own. Being chosen by one of the leading families to manufacture such essential items as arrows enhanced the status of the arrow maker as well. Such contract work could therefore lead to a reciprocal gain in prestige for the customer and the craftsman.

A man who had lost the ability to hunt big game or to lead war parties, either through old age or injury, could still substantially contribute to his family’s and his community’s sustenance, defense, or even wealth by making arrows. Bowers, for instance, mentioned two Mandan men who had lost the use of their legs through injury. These men became expert arrow makers and sustained their families solely through the sale of their products.

Ownership Marks on Arrows

Many arrows in the Plains were painted with one or more colors at the back, underneath the fletching. Among most Plains peoples, each archer had his own way of painting his arrows, and these marks clearly indicated to whom an arrow belonged. After a hunt the marks helped determine which hunter had killed which animal. If several arrows belonging to different hunters hit the same animal, the ownership marks showed whose arrow had delivered the killing wound.123 Because practically every able Plains Indian male was an archer who owned at least one quiver full of arrows, Plains encampments or villages all had a multitude of arrows. However, their specialized construction characteristics meant that arrows were not necessarily interchangeable and made it difficult to use someone else’s arrows. Therefore clear individual ownership markings helped prevent arrows from getting mixed up.

An archery set examined at the Manitoba Museum has different markings for different types of arrows. The markings were all done in the same color sequences, perhaps indicating the same owner, but arrows with bladed metal points were marked in a pattern different from that applied to small game arrows or bird blunts. This made it easy for the archer to recognize each kind of arrow quickly by glancing into the opening of his quiver, without having to pull out the entire arrow and examine the arrowhead to determine its function.124 Most men were probably familiar with the arrow markings of every archer in their community. Some may even have recognized the markings of relatives and friends in other bands and villages. In the same way warriors were probably able to recognize the arrow markings of individual enemies they had fought, whose arrows they had seen up close.

The highly individualistic nature of Plains Indian warfare, at least during the mid- and late nineteenth century, was reflected in the importance that was given to the identification of whose arrow had made a kill. The practice also helps us to understand another Plains Indian custom, often considered a manifestation of wanton brutality and extreme violence by non-Aboriginal people. The Cree/Pikani elder Saukamappee related to David Thompson in 1787 that for the Cree, Assiniboine, and Blackfoot it was important for spiritual reasons to clearly determine which warrior had killed which enemy. This became difficult when his people first used firearms in battle, because bullets did not have ownership marks and were difficult to retrieve.125 The slayer of an enemy killed by an arrow, on the other hand, could be identified by the ownership marks on the arrow. As Peter Fidler, then in charge of the HBC post of Brandon House, wrote in September 1817: “A few Cree went in search of the Indian lately missing. They found him shot thro the Body. Two arrows sticking in the same part and scalped—but no otherwise mutilated—and all his clothes left on him, but his arms & ammunition missing. They found 4 balls on the Ground near where he lay & some powder spilt, & they imagine he took this in his last attempt to defend himself.”126