Aboriginal Peoples and Firearms

Europeans’ introduction of firearms to Aboriginal peoples has often been considered a major catalyst for momentous changes in political, economic, and military relations between different Aboriginal groups and also between Aboriginal people and Europeans.1 In 1940 David Mandelbaum stated: “Even before the days of white influence, the Cree seem to have been an aggressive, warlike people. Upon being provided with firearms by the English, they easily overrode opponents who as yet had only aboriginal weapons. For a time the only limit to the extent of Cree conquests was that of sheer distance separating the regions of their farthest forays from the base of European supplies.”2

Scholars have also often explained European ascendancy over Indigenous peoples in the Americas largely in terms of technology.3 For example, Jared Diamond stated about the Spanish conquest of the Inca empire: “Pizarro’s military advantages lay in the Spaniards’ steel swords and other weapons, steel armour, guns, and horses. To those weapons, Atahuallpa’s troops, without animals on which to ride into battle, could oppose only stone, bronze or wooden clubs, maces and hand axes, plus slingshots and quilted armour. Such imbalances of equipment were decisive in innumerable other confrontations of Europeans with Native Americans and other peoples.”4

However, critics of such views have pointed out the many disadvantages of early firearms, especially in comparison to the bow and arrow and other indigenous North American weapons systems.5 Nonetheless, European and Aboriginal observers during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries considered firearms to have had a major impact on Aboriginal intertribal military relations.6 For example, fur trader and explorer David Thompson noted that during the late 1700s and early 1800s, “iron heads for their [Pikani] arrows are in great request but above all Guns and ammunition. A war party reckons its chance of victory to depend more on the number of guns they have than on the number of men.”7 In regard to the Swampy Cree on the coast of Hudson Bay, Thompson went even further by stating that if they were deprived of guns, they would no longer be able to provide for themselves by using bows and arrows.8

On the other hand, contemporary writers have indicated the technical flaws and logistical problems connected to muzzle-loading, single-shot firearms.9 These apparently contradictory assessments seem especially stark for the Northern Plains, where the introduction of firearms has been connected to momentous changes in the military relations among different Indigenous groups, but where bows and arrows remained in use as combat and hunting weapons until the destruction of the bison herds in the late nineteenth century.10

To shed more light on these questions it is necessary to closely examine the major types of firearms available to Aboriginal people through the fur trade and to describe the manner of their use. It is beyond the scope of this study to cover every type of firearm available to Aboriginal people from 1670 to 1870. Rather, muzzle-loading, smoothbore long guns will be emphasized because these were the first firearms introduced to Aboriginal peoples of the Plains and Subarctic, and they comprised the majority of firearms available to these people until the mid- to late nineteenth century. It is the introduction of these guns that is generally credited with having altered Aboriginal cultures, hunting methods, and military relations. By the time breech-loading or repeating firearms became available, specific patterns of firearms use had already developed in the Plains and Subarctic, based on Aboriginal experience with smoothbore, muzzle-loading firearms.

Types of Firearms Sold in the Fur Trade

English gun making was not very well developed in the seventeenth century, and many guns sold by English companies were of Dutch or German manufacture. However, by the late seventeenth century English gun making had improved and expanded.11 From approximately 1650, muzzle-loading smoothbore firearms were the standard weapons in Europe and among Europeans in North America. Muzzle-loading rifles, guns with spiral grooves (rifling) inside the barrel to increase range and accuracy by increasing the spin of the bullet, were primarily manufactured for sportsmen and hunters, while smoothbore guns remained the main weapon for military purposes into the 1850s, when ammunition in metal cartridges and breech-loading guns began to gain prominence.12

Muzzle-loading firearms differed mostly in their lock types. Most of these weapons needed two kinds of powder. They had to be loaded with coarse powder for the main charge, often followed by a patch or wad and a lead ball or shot. The main charge was then ignited by fine priming powder in the pan. The pan was connected to the inner end of the barrel by a small bore, so that when the fine priming powder in the pan was ignited, the flame from the priming powder could reach the main charge. Major improvements in muzzle-loading firearms consisted mainly of different ways to ignite the priming powder.13

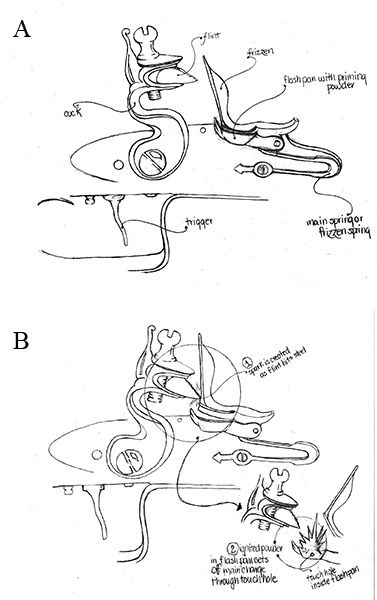

Fig. 44. Flintlock mechanism. A: Parts of the flintlock mechanism. B: The ignition system of the flintlock mechanism. Drawings by Margaret Anne Lindsay.

Throughout the seventeenth century, muzzle-loading matchlock weapons were common. In matchlock weapons, a burning match cord was pressed into the pan to ignite the priming powder. Matchlocks had several disadvantages, and Swampy Cree traditions tell of frequent accidents with them.14 Because these weapons required a constantly burning match when in use, accidents with unintentionally ignited powder were common. The smoke from the burning match made concealment of the user difficult, and the smell may have alerted enemies or animals to the hunter’s presence. Furthermore, they were very heavy and had to be supported on a forked rest when firing. This made it very awkward to fire the weapon from a crouching position or at moving targets, as was commonly necessary when hunting.

By the early eighteenth century the more reliable and less complicated flintlock superseded the matchlock. Its main advantage was that the constantly burning match was replaced by a piece of flint, held in the hammer of the flintlock. When the trigger was pulled, a spring pushed the hammer down. This made the flint strike the frizzen and cause a spark. The spark then fell into the pan and ignited the priming powder, which ignited the main charge (see Fig. 44).15

Although the flintlock was much safer and more convenient than the matchlock, it still had several disadvantages. The powder in the pan caused a highly visible flash and created a great deal of smoke. The flashes of pan and muzzle and the cloud of smoke hanging in the air after the shot all revealed the gun’s position. Keeping the powder dry was another major problem. As well, reloading the weapon in the regular manner was slow. This factor has often been pointed out as the major disadvantage of flintlock firearms in comparison to bows and arrows.

Rate of Fire of Firearms and Bows

Loading and firing a muzzle-loading flintlock gun in the regular manner involved several steps and considerable effort. The hammer had to be placed at the “half cock” position and a priming powder charge had to be poured into the open pan, which was then closed by pulling back the steel (frizzen).16 Then the butt of the gun was placed on the ground, powder was poured down the muzzle and the wadding and ball were inserted. The ramrod was drawn from its position underneath the barrel, turned and inserted into the muzzle to push wadding and ball down the muzzle and firmly seat them against the powder charge. This step was important, since a gap between the powder charge and the ball could result in the breech of the gun exploding into the user’s face and hands. Sometimes a second piece of wadding was added to prevent the musket ball from rolling away from the powder charge and out of the barrel. Next, the ramrod was withdrawn from the muzzle and placed back into its fittings underneath the barrel. Then the piece could be cocked and fired.17

The loading speed further depended on whether the weapon was a smoothbore or had a rifled barrel. With smoothbores, balls of a considerably smaller diameter than the inner diameter of the barrel could be used, which made them glide down the barrel much more easily, thus reducing loading time, but at the expense of accuracy and range. With a rifled barrel, the ball had to fit tightly for the rifling to impose a spin on the bullet in order to increase accuracy, but forcing it down the barrel took more time than inserting a loose-fitting one.18 There are several estimates of the rate of fire that could be achieved with smoothbore military firearms of the late eighteenth century, such as the British “Brown Bess,” which was the standard weapon of British troops during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. The average estimate was that a well-trained soldier could fire three shots per minute, so long as no careful aiming was required.19

While ethnographers and anthropologists recorded several accounts of older relatives or tutors training Aboriginal boys in archery, there is little information on how and from whom Aboriginal people acquired knowledge in the use and maintenance of firearms.20 HBC officer Andrew Graham recorded: “When I commanded Churchill Factory Anno Domini 1773, 4 and 5 I trained up four young Esquimaux to use fire-arms, and left them fully a match for our best Indians, either at an object sitting or on the wing.”21

In the early twentieth century, the Blood Indian Three Bears related a story detailing how the Blood received their first firearms as gifts of peace from the Cree in exchange for horses. The Cree were said to have set up targets and taught the Blood leaders how to use these weapons.22 Another account recorded in the 1950s by Joe Little Chief, a Blackfoot from Cluny, Alberta, described how European traders came to the Blackfoot country by boat, sold the first firearms to the people, and taught them how to load and fire these weapons.23 However, it is likely that for the most part, after some initial instruction by fur traders or Aboriginal middlemen who sold the weapons, or by some more experienced fellow tribesmen, Aboriginal people gained their mastery of firearms largely by trial and error.24

While this manner of learning could be dangerous and accident prone, it left the learners free to take an approach to handling firearms that could differ from European military regulations. Aboriginal people had no military practice manuals or drill sergeants to worry about, yet they were very keen to achieve the results they wanted with the equipment available to them. Free of military drill and regulations, an experienced user could overcome the slow loading speed by using several risky shortcuts in loading and priming a muzzle-loading weapon, especially if it was a flintlock. Keeping a powder charge in the gun long before the shot, and then only adding the bullet when needed, was one way to cut back loading time. Aboriginal people in the Plains often kept a second powder charge ready in one hand and several musket balls in their mouths, ready to spit them into the muzzle in order to save time when reloading.25 This was especially important when using a muzzle-loading gun on horseback at high speeds. However, while it was possible for experts to reload their muzzle-loading firearms on horseback at a gallop, most gun users had to dismount to reload their weapons.26

As Maurice Doll has demonstrated, for smoothbore weapons the use of a ramrod and wadding could be avoided by simply banging the gunstock on the ground sharply, to make a more loosely fitting bullet slide down the barrel and rest directly against the previously inserted powder charge. Instead of using fine powder from a special dispenser for priming the pan, the weapon could be tilted on its side so that the canal between priming pan and main chamber pointed slightly downward. A sharp rap against the side of the breech would then cause some powder from the main chamber to spill onto the pan. Thus, the weapon could be primed in an instant. Using such quick but risky loading methods, users could fire a flintlock smoothbore musket up to six times a minute.27

Also pointing to such quick-loading methods are some Blackfoot stories dealing with supposedly magical ways to fire guns without powder and lead, yet with deadly effect. The Piegan elder James White Calf told linguist Richard Lancaster in the late 1950s that certain men among the late nineteenth-century Piegan had obtained magical control over firearms in dreams or visions. However, Lancaster believed that what White Calf described was actually a quick reloading and shooting method for muzzle-loading guns used by frontiersmen and Aboriginal people alike.28 This method was similar to that demonstrated by Maurice Doll—one made to appear as if there were no powder and bullets involved in the process, because the time-consuming steps of using priming powder and a ramrod to push the ball down the barrel were omitted.29

But even if such shortcuts were used, archers could still far surpass users of muzzle-loading single-shot weapons in their shooting speed. In the time it took to even quick-load a muzzle-loader, a well-practiced archer could shoot three arrows or more. Archery games and contests were very popular in the Plains. One involved an impressive rapid shooting technique: the objective of the game was to keep as many arrows in the air, before the first arrow, launched as high as possible, returned to the ground. According to the American artist and ethnographer George Catlin, who in 1832 observed this game being played at a Mandan village in present-day central North Dakota, experts could shoot eight arrows before their first one hit the ground.30

Catlin commented in detail about the use and mode of shooting among the Mandan and other Plains peoples. His observations are crucial to understanding the actual use of the bow and arrow by Plains peoples in combat and in bison hunting on horseback.

I have seen a fair exhibition of their archery this day, in a favourite amusement which they call “the game of the arrow,” where the young men who are the most distinguished in this exercise, assemble on the prairie at a little distance from the village, and having paid, each one, his “entrance fee,” such as a shield, a robe, a pipe, or other article, step forward in turn, shooting their arrows into the air, endeavouring to see who can get the greatest number flying in the air at one time, thrown from the same bow. For this, the number of eight or ten arrows are clenched in the left hand with the bow, and the first one which is thrown is elevated to such a degree as will enable it to remain the longest time possible in the air, and while it is flying, the others are discharged as rapidly as possible; and he who succeeds in getting the greatest number up at once, is “best,” and takes the goods staked.

In looking on at this amusement, the spectator is surprised; not at the great distance to which the arrows are actually sent; but at the quickness of fixing them on the string, and discharging them in succession; which is no doubt, the result of great practice, and enables the most expert of them to get as many as eight arrows up before the first one reaches the ground.

For the successful use of the bow, as it is used through all this region of country on horseback, and that invariably at full speed, the great object of practice is to enable the bowman to draw the bow with suddenness and instant effect; and also to repeat the shots in the most rapid manner. As their game is killed from their horses’ backs while at the swiftest rate—and their enemies fought in the same way; and as the horse is the swiftest animal on the prairie, and always able to bring his rider alongside, within a few paces of his victim; it will easily be seen that the Indian has little use in throwing his arrow more than a few paces; when he leans quite low on his horse’s side, and drives it with astonishing force, capable of producing instant death to the buffalo, or any other animal in the country.

The bows, which are generally in use in these regions, I have described in a former Letter,

And the effects produced by them at the distance of a few paces is almost beyond belief, considering their length, which is not often over three, and sometimes not exceeding two and a half feet. It can easily be seen, from what has been said, that the Indian has little use or object in throwing the arrow to any great distance. And it is very seldom that they can be seen shooting at a target, I doubt very much whether their skill in such practice would compare with that attained to in many parts of the civilized world; but with the same weapon, and dashing forward at fullest speed on the wild horse, without the use of the rein, when the shot is required to be made with the most instantaneous effect, I scarcely think it possible that any people can be found more skilled, and capable of producing more deadly effects with the bow.31

Some contemporaries, such as the ethnographer George Bird Grinnell, who also had had extensive contacts with Northern Plains peoples, considered Plains Indian archery at least as effective as early revolvers: “At the most effective range—say from forty to seventy yards—an Indian could handle a bow and arrows more rapidly and more effectively than the average man could use a revolving pistol of that time. . . . Stories are told of an occasion when the Cheyennes armed with [sinew-backed] bows kept off an attacking party of Crows who had some guns.”32

Because of this high shooting speed and the often very short distances of combat, victims of Aboriginal archery often received multiple arrow wounds, and probably a higher number of serious injuries, thus disabling an opponent more quickly.33 Thus, under equal conditions, an experienced archer could exceed the shooting speed of even an experienced user of a single-shot muzzle-loading firearm. This superiority of bows and arrows began to fade only with the advent of revolvers in the late 1830s and the introduction of breech-loading and repeating firearms using cartridge ammunition in the 1860s.34

Emergence of the “Northwest Gun”

When the “Brown Bess” was adopted as the standard English military firearm in 1705, it probably freed large numbers of older and lighter English military guns for sale.35 At this time, the common English light sporting or general-purpose musket was referred to as a “fusil.” These weapons were similar to a military musket but were of a lighter caliber. They comprised the majority of firearms traded to Aboriginal people at the time.36

A list of standard HBC trade goods from 1748 includes “Guns, 4 foot . . . 31/2} foot . . . 3 foot.”37 This probably refers to guns of barrel lengths of 48 inches (4 feet), 42 inches (3.5 feet), and 36 inches (3 feet), implying a certain degree of standardization in firearms manufacture. These weapons were the precursors of a smoothbore flintlock weapon that became most popular among Aboriginal peoples in North America after the fall of New France in 1760. It was known as the “Northwest Gun.” This term referred to the area where these weapons were sold and not to the North West Company of Montreal, which was founded later. Another name for this firearm was “London fusil,” after the city where most of them were manufactured.38

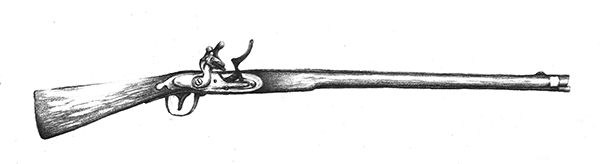

Fig. 45. Generic “Northwest” trade gun. The Hudson’s Bay Company, the North West Company, the American Fur Company, the Mackinaw Company, and the U.S. Indian Trade Office all sold or distributed such weapons to Aboriginal people during the nineteenth century. Drawing by Margaret Anne Lindsay.

Montreal merchants recognized the demand for more reasonably priced firearms among the Aboriginal people of the Great Lakes region. They requested English gunsmiths to manufacture a light and cheap but serviceable firearm that could be used with ball and shot. The resulting product incorporated as many manufacturing shortcuts as possible. The curved butt plate was replaced by a straight one made of sheet brass, and the ornamental trigger guards were replaced by plain ones of iron, but were made wider to allow the use of mittens and gloves when firing the weapon. Decoration was reduced to a side plate in the shape of a sea serpent or dragon, which could be cheaply cast in a mold (see Fig. 49).39

Despite all these shortcuts, trade guns were still not cheap. At York Fort in 1689–90 a “short” gun cost ten marten pelts and a “long” gun twelve, while four marten pelts corresponded to one beaver pelt in value.40 John Oldmixon recorded in 1708:

The STANDARD how the Company’s Goods must be barter’d in the Southern Part of the Bay.

Guns. One with the other 10 good Skins; that is, Winter Beaver; 12 skins for the biggest sort, 10 for the mean, and 8 for the smallest.

Powder. A Beaver for half a Pound.

Shot. A Beaver for four Pounds.

Powder-Horns. A Beaver for a large Powder-Horn and two small ones.41

In 1715 the HBC paid 20 shillings per gun, while the British Board of Ordnance paid 22 shillings for each Brown Bess musket.42 However, these prices fluctuated depending on how much the HBC was willing to pay its gunsmiths. For example, the company paid 21 shillings in 1713–14, 20 shillings in 1715–16, and 23 in 1717, probably because of varying quality and price agreements with the gunsmiths. In 1716 James Knight complained that the guns he had to sell did not meet the quality of those he had sold in 1714. In this instance poor quality may reflect an attempt by the HBC to reduce costs.43 Overall, from 1680 to 1728 the price the HBC paid for guns remained fairly stable, around 22 shillings, with a price increase up to 26 shillings in 1698, while 24 shillings was common in the first decade of the eighteenth century.44

In France each trade gun cost 10 francs and 10 sols in 1701. In North America the French Canada Company sold a pound of shot or three gunflints for one beaver skin in 1742. A pound of powder cost four skins, a pistol cost ten, and a gun cost twenty skins.45 The HBC also charged twenty beaver skins for a trade gun at that time and still maintained this price a century later.46 During the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century the North West Company and American fur trade firms also sold trade guns of the Northwest type in great quantities. In 1833 Prince Maximilian observed at Fort Union on the Upper Missouri in western North Dakota that “most of the Assiniboine people [who visited the fort] have guns, the stocks of which they ornament with bright yellow nails, and with small pieces of red cloth on the ferrels [“ferules”] for the ramrod.”47 These were “the common Mackinaw guns, which the Fur Company obtains from England at the rate of eight dollars a-piece, and which are sold to the Indians for the value of thirty dollars.”48 In the United States these weapons were not only sold by fur traders but also distributed by the U.S. government as part of treaty payments after American independence in 1783. The Northwest gun eventually became the principal firearm not only for Aboriginal people but also for trappers and Métis.49

Northwest guns used the lightest ball that could still be effective against big game, yet its bore was large enough to use the weapon as a shotgun. Because it was a smoothbore, even makeshift projectiles could be used when regular ammunition was lacking. Northwest guns were mostly 24-gauge (about .58 caliber) and were bored for using a 30-gauge ball.50

Trading companies generally stocked guns with barrel lengths from 76.2 to 121.92 centimeters (30 to 48 inches). These barrel lengths were the same as those of other muzzle-loaders used by non-Aboriginal people on the frontier at that time.51 According to Arthur J. Ray, shorter guns of about three feet in length became popular with the Parklands and Plains peoples, while Aboriginal people living in the northern forest seem to have preferred the longer four-foot models. Natives in boreal forest regions often hunted individual animals such as moose at greater distances, requiring an accurate shot at medium to long range, which was facilitated by a longer gun barrel. In dense underbrush, bullets were not deflected by branches as arrows might be, an important consideration when shooting at a distance of 20 meters or more in dense bush. Furthermore, a bullet could kill an animal instantly, while an arrow wound might not cause instant death, obliging the hunter to track it for some distance. In the Parklands and Plains, however, long-distance shots were not of such crucial importance. A gun’s ease of handling on horseback was a more important consideration in the Plains and may explain the Plains peoples’ preference for shorter guns.52

Most Aboriginal people preferred a firearm that was powerful enough to kill big game at close range but light enough to be carried all day with comfort. Judging by recovered weapons fragments from archaeological excavations at Iroquois village sites in upstate New York, dating from the mid-seventeenth to the mid-eighteenth century, Iroquois people used light but sturdy weapons, adequate for hunting and close-range combat.53 In 1808 a party of Kainai (Blood) and Gros Ventre des Prairies attacked American trappers working for Manuel Lisa on the Missouri. Subsequently they brought some of the items taken from the Americans to Edmonton House where the post journalist recorded: “Amongst other plunder, they have brought us a rifle Gun which, on account of its weight, they consider as of little Value.”54

By the middle of the eighteenth century double-barreled shotguns, at first with flintlocks, became popular among those Aboriginal groups with regular access to trading posts.55 According to Louis Bird, Omushkego-Cree people considered these weapons a great improvement from the earlier single-shot weapons: “One other thing about the gun is that the first one only shot once and then they improved and a new design was a double barrel and that’s improved more. And improved their hunting technique and also improved their lifestyle; after that it was the repeating rifle that was very good for the big game animals.”56

In the 1820s another ignition mechanism, the percussion lock, was introduced. With this new system, flint, frizzen, pan, and priming powder were replaced by a percussion cap that already contained a priming charge. This system was much less affected by wind and dampness than the flintlock. Its disadvantage to Aboriginal people was that they had to purchase percussion caps suited to their model of gun at a trading post, while material for gunflints for a flintlock could be picked up wherever flint naturally occurred. However, many flintlock trade guns were converted to the new ignition system and eventually even manufactured with the percussion lock.

Pistols, too, were also popular with Aboriginal people. They were easier to carry than guns, could be concealed under clothing, and could be used more easily when fighting inside buildings, such as trading posts.57 Pistols were also well suited to the closeup style of fighting that increasingly came to dominate combat, at least among the Plains peoples. On occasion, Aboriginal people in the Plains shortened the barrels of their trade guns for easier handling on horseback. Sometimes the barrels were cut extremely short and most of the gunstock was cut off to convert the gun into a heavy pistol.58 The cut-off Northwest gun barrels were sometimes recycled into hide fleshing tools that resembled earlier types made from bison or elk leg bones.59

On January 6, 1789, William Walker at the HBC’s South Branch House on the lower South Saskatchewan River wrote to William Tomison requesting more “Guns, Pistols, Bayonnets flat, cloth and a few Hatchets.” According to Walker, these items were in great demand among the Aboriginal people near his post.60

New Types of Firearms and Improvements in Firearms Technology

The great breakthrough in firearms technology came with the invention of the Colt revolver in 1836. Texas Rangers first used these weapons in combat on a large scale against Comanche people and other Aboriginal groups in the Southern Plains. Compared to the cumbersome muzzle-loading single-shot Kentucky rifles the rangers had used earlier, revolvers provided greater firepower and a higher rate of fire. Furthermore, revolvers were much easier to use from horseback than the long-barreled Kentucky rifles. Earlier the Texas Rangers had to dismount and use their long-barreled rifles from hastily constructed fortifications. This meant that the initiative always lay with their Aboriginal opponents, who fought from horseback and thus had greater mobility and speed. However, the new revolvers enabled the rangers to fight while mounted and to successfully pursue raiding parties deep into their homeland. By the early 1840s the Texas Rangers began to use revolvers with increasing success against the Comanche and other Southern Plains peoples.61 In 1851 an improved model, the Navy Colt cap and ball revolver, was introduced.62 A similar firearm was the Star revolver .44, introduced in 1863.63 The advantages of the revolver made this weapon desirable to Aboriginal people in the Plains, and eventually they acquired increasing numbers of these firearms.

By the mid-nineteenth century, fixed-cartridge ammunition and breech-loading firearms were developed. These weapons quickly gained prominence, especially among non-Aboriginal civilians on the frontiers of North America. From the mid-1860s onward, breech-loading single-shot carbines and repeating rifles became highly popular among the Plains peoples. After the American Civil War, Blackfoot groups such as the Piegan, who traded with American traders in north-central Montana, and also Métis people, gained access to large numbers of surplus U.S. military carbines, as well as various types of repeating rifles. James Willard Schultz, who lived and traded among the Blackfoot, wrote that he sold dozens of Henry repeating rifles to the Blackfoot, Cree, and Assiniboine during the 1870s.64 Nevertheless, Blackfoot people also continued to purchase the standard smoothbore trade guns from the HBC. Schultz described trade guns he saw among the Blackfoot in the 1860s and 1870s: “The old Hudson’s Bay Company flintlock guns were about the length of the powder and ball muzzle-loaders that our army used in the rebellion of the Southern States, and the balls were thirty to the pound. The Indians always profusely ornamented the stock and forearms with brass tacks.”65

Aboriginal people manufactured some of the accoutrements necessary to use a firearm. For example, gun cases made from Native tanned leather, sometimes elaborately decorated with quill- or beadwork, from Subarctic and Plains cultures can be found in many museum collections. Two Leggings related that his older brother Wolf Chaser bought a muzzle-loading gun for him and that he subsequently manufactured his own powder horn and buckskin shot pouch, wearing these items attached to the same carrying strap. He also carried a long forked stick as a support for the barrel of his gun, similar to sixteenth-century Spanish firearms.66 Prince Maximilian observed: “Like all the Indians[,] they [the Assiniboine] carry, besides, a separate ramrod in their hand, a large powder horn, which they obtain from the Fur Company, and a leather pouch for the balls, which is made by themselves, and often neatly ornamented or hung with rattling pieces of lead, and trimmed with coloured cloth. All have bows and arrows; many have these only, and no gun.”67

The Hudson’s Bay Company stuck to its established product, the muzzle-loading trade gun, and refused to sell repeating firearms of any kind to Aboriginal people. By the 1860s and 1870s only a few of these Northwest guns were flintlocks, as most were percussion models. The HBC’s refusal to sell repeating firearms put the Plains Cree and Assiniboine at a serious disadvantage in their hostilities with the Blackfoot.68

As violent conflict in the Plains intensified and more advanced firearms technology became available to Aboriginal people, muzzle-loading smoothbore firearms faded in importance. When a group of Lakota and Cheyenne surrendered their weapons to the U.S. military in 1877, there were 160 muzzle-loaders among them. Two of these were flintlocks and only one was a smoothbore; all the others were percussion locks, nearly all of them rifles.69 Although breechloaders became relatively common among the U.S. Plains Indians during the 1870s, muzzle-loading percussion rifles continued to be of importance. A Cheyenne explained it thus: “The muzzle-loaders usually were preferred, because for these we could mold the bullets and put in whatever powder was desired, or according to the quantity on hand.”70 Apparently the slower reloading speed of muzzle-loading rifles did not cause Cheyenne warriors to stop using these weapons.

The HBC introduced percussion trade guns in 1861, but the older flintlock models remained in stock for decades thereafter, although their production numbers declined. In its percussion-cap version, the Northwest gun was still in effective use by Aboriginal people in northern Canada in the 1880s.71

Quantities of Firearms Sold to Aboriginal People in the Fur Trade

Numbers of gun sales to Aboriginal people are difficult to obtain for the period before 1800. The minutes of HBC board meetings list 170 fowling pieces, together with powder and shot as cargo in an outgoing ship in 1670 and 200 fowling pieces and ammunition in 1671.72 In 1683 the HBC sold a total of 363 guns, thirteen at Rupert River in the southeast of Hudson Bay, twenty-six at Hayes Island on the Moose River (an early site of Moose Fort), and 324 at Albany River (Albany Fort).73 Yearly shipments varied greatly, from a high of 1,273 to as low as 100 for 1688.74 Most of these firearms probably went to Aboriginal people in the Hudson Bay area. T. M. Hamilton estimated that on average the HBC sold approximately 476 guns per year.75

From 1775 to 1780 a total of 3,947 firearms were sold at Fort Michilimackinac.76 Aboriginal middlemen then traded many of these weapons to Aboriginal groups living farther west. After an initial glut in the 1760s, the numbers of firearms sold to Aboriginal people in the Northern Plains during the last two decades of the eighteenth and through the early nineteenth century seems to have been rather low. If the eighteen guns and four pistols in stock at Manchester House in April 1787 were representative, it would point to a rather low number of firearms being sold at HBC posts in the region. Similarly, four years later William Tomison complained about not having enough guns and pistols to trade. He wrote that he even had to borrow three pistols from his own employees to trade to his customers.77

In November 1792 Tomison, trading with Sarcee people at the HBC’s Buckingham House, noted: “finished trading with the [Sarcee] Indians and they went away, these have brought 550 parchment Beaver, which is the most I ever saw this Tribe bring, I had 28 Guns when they came but now they are reduced to 18.”78 A few months later the supply of firearms for sale to Aboriginal people was almost depleted at Buckingham House. James Tate, then in charge of the post, wrote to his superior on March 1, 1793: “My Trade at present amounts to 4000 parchment Beaver and 500 Wolves with very little of any other kind, and there has been no Muddy river Indians [Pikani] in since the fall, and very few of Blood Indians and what I am to do with them for want of Guns I know not, as I have but 5 left, it grieves me to lose Indians for want of goods.”79

In December 1831 a group of Piegan trading with James Kipp of the American Fur Company turned in 6,450 pounds of beaver, receiving 160 guns in exchange. They intended to use them against their western neighbors.80 Looking at sales figures for the HBC posts Brandon, Cumberland, and Carlton House from 1811 to 1814, Arthur J. Ray was able to show that the total numbers of firearms sold at these three posts were such that only one in ten families of Aboriginal customers ended up owning a gun.81 At first glance such sales figures seem rather low, but without more precise information on the population numbers of the Aboriginal groups who came to trade, it is difficult to estimate how many Aboriginal people carried firearms and what percentage of their community they represented. Furthermore, other traders competing with the HBC were active in the region and Aboriginal people could have obtained some of their firearms through Aboriginal middlemen as well. This makes it very difficult to assess the total numbers of firearms sold to Aboriginal people.

In order to determine how well armed the Northern Plains peoples were, it would be beneficial to relate firearms sales figures to the population numbers of the Aboriginal customers.82 However, this is difficult, because often fur traders did not specify the numbers of persons, or “lodges” or “tents,” in the Aboriginal groups who came to trade at their posts. In a rare instance, William Tomison noted in early December 1793 that four tents of Sarcee traded ten guns at Buckingham House. This was more than half the total number of guns Tomison had at his post.83 Unfortunately, Tomison did not specify how many people lived in one tent, whether they were middlemen trading with other Aboriginal groups, or whether they bought these firearms for their own use only. The Blackfoot White Eagle mentioned a wealthy late nineteenth-century Blackfoot named Elk Bull (Po-nok-se-ta-mek) and his wife, Only Woman (Ne-je-ta-ke). Elk Bull was so well off that he owned “4 guns, 2 bows and arrows, 1 Medicine Pipe 2 axes and a lot of horses.”84

Over the next two and a half decades the numbers of firearms available at least to some Aboriginal groups in the Plains rose sharply. In early 1818 Peter Fidler observed at the HBC’s Brandon House that “the Mandan now at the Cree Tents 40 miles off will soon return, some others came with him from the villages but their wives prevailed on them to return our Inds say some of the Mandans have from 6 to 10 Guns and every Man one at least keeping them carefully for Defence.”85

Unfortunately, it is extremely difficult to correlate the numbers of firearms among the Mandan with their population. Population estimates for the Mandan before the smallpox epidemic of 1837 vary widely, and the 1781 smallpox epidemic may already have left fewer than fifteen hundred individuals.86 When George Catlin visited the Mandan villages in 1832, he estimated the population at two thousand persons. Prince Maximilian, who visited the Mandan a year later, thought there were between nine hundred and one thousand. In 1835 and 1836 the annual report of the U.S. Commissioner of Indian Affairs listed the Mandan with a population of fifteen thousand. However, the report for 1837, before the epidemic, gave a figure of only thirty-two hundred.87

Population estimates for the different Blackfoot groups who were major customers of the HBC are similarly confusing for the first half of the nineteenth century. Population numbers were of practical importance to fur traders because they needed to know the number of potential customers in an Aboriginal group and also the number of warriors, in case of impending hostilities. Fur traders who counted Plains Indian populations in terms of lodges generally assumed seven to ten people lived in one lodge, of whom three were considered warriors. The Blackfoot Eagle Ribs stated in 1938 that “a good sized band comprises 20 tipis (each full of people). This is the best number for efficiency’s sake.”88 According to the traders’ estimates, this would put the number of persons in the band at 140 to 200.

In 1809 Alexander Henry the Younger estimated the total population of the Piegan/Peigan, Blackfoot, and Blood at 650 lodges with 1,420 warriors. Allowing an average of eight persons per lodge, this would make a total of approximately fifty-two hundred people. In 1832, when George Catlin visited with Piegan people at Fort Union on the Upper Missouri (on the present Montana–North Dakota border), he obtained very different information from his Piegan hosts. He estimated the total Blackfoot population at 16,500 persons, averaging ten persons per lodge. His estimate, however, is still lower than that of Prince Maximilian, who in 1833 estimated the total Blackfoot population at eighteen thousand to twenty thousand persons.89 In 1854 James Doty, assistant to the newly appointed governor of Washington Territory, Isaac Stevens, again estimated lower total population numbers for the Blackfoot groups. In his estimate there were 850 lodges with a total of 7,630 persons. Of these, 2,550 were warriors.90 The devastating smallpox epidemic of 1837 may account for the lower population numbers.

Judging from the number of surviving trade guns from the period after 1820, and also from 1780 to 1820, Charles Hanson argues that a very large number of these weapons must have been sold to Aboriginal people. Applying an estimated “rate of survival,” Hanson compared the numbers of firearms purchases of the American Fur Company with the numbers of surviving similar specimens today and arrived at a ratio of about one in a hundred.91

However, the fluctuation in the number of firearms sold to Aboriginal people needs to be considered. In some years only a few weapons reached their customers, while in other years large numbers of guns and pistols were sold. Furthermore, it can be assumed that those Aboriginal people with direct access to a trading post obtained higher numbers of firearms than those who had to trade through Aboriginal middlemen or had no access to European trade goods at all. The Upper Missouri villages, for instance, were a major trade center linking Aboriginal customers from the Plains and the Parklands with European trade from Hudson Bay, Montreal, and St. Louis. Therefore, the Mandan were in an ideal position to obtain large numbers of firearms. The Mandan carefully chose whom to trade them with, making sure these weapons would not be turned against their former owners. The Blackfoot-speaking peoples and other Plains groups who traded directly with the HBC and the Montreal-based traders also obtained a more or less steady supply of firearms and ammunition. On the other hand, Aboriginal groups in the Rocky Mountains, such as the Eastern Shoshone and the Kutenai, had comparatively little access to European trade and firearms.

Servicing of Firearms

Muzzle-loading flintlock guns came into such universal use that Aboriginal people eventually learned the basics of gunsmithing to service their own weapons. Over time, specialists emerged, similar to the expert bow and arrow makers discussed in the previous chapter. A large cache of seventeenth-century gun parts was found in the 1950s at a New York Iroquois site. Another cache of flintlock parts came from a Pawnee village in modern Nebraska, dating approximately to 1820–45.92 This archaeological evidence shows that at least some Aboriginal groups in the Eastern Woodlands and Great Plains took care of minor repairs or exchanged damaged parts of their firearms.

However, gun repair often required the use of a forge, an anvil, and other specialized tools not usually available to Aboriginal people. This and the inferior quality of certain gun parts, such as springs, made the refurbishing of firearms before sale almost a standard practice at HBC posts. It often involved considerable work and sometimes included the replacement of not only springs and locks but also gunstocks, which were frequently manufactured at the posts.93 Before the introduction of the Northwest gun, firearms were individual, more or less “custom made” weapons. Thus no two guns and their individual parts were exactly alike. From the 1760s on, with the advent of the Northwest gun, a certain degree of standardization entered large-scale firearms manufacture. Northwest guns were relatively standardized for mass production. Therefore parts were interchangeable to some extent. These guns were considerably less expensive than rifles of the period.94 However, industrial mass production of firearms, and thus the interchangeability of parts, did not occur on a larger scale until the first decades of the nineteenth century.95

The HBC provided liberal technical support for Aboriginal peoples’ firearms purchased from the company, often as an inducement for newcomers to continue trading with the HBC. Post journals frequently referred to the post blacksmith or the armorer repairing Aboriginal peoples’ firearms, often on credit. At Albany in 1784, for example, the armorer was “repairing Indians guns several of whom took debt.”96

Similarly, in the Plains, the Buckingham House journal shows the entry “the Smith repairing an Indian Gun” three times for the period from January 5 to February 18, 1793.97 Servicing of a firearm was also provided to an old Blood Indian man, who had come to Manchester House with his family for the first time, as an inducement for him to come back. He had probably obtained his gun from other Aboriginal people, before directly trading with HBC personnel.98 Servicing firearms was also provided for a whole encampment of Gros Ventre des Prairies (Fall Indians).99 However, when in November 1786 an Aboriginal man brought a so-called French gun, which had probably been obtained from the North West Company, to Manchester House for repairs, servicing was refused, likely because the weapon had come from the HBC’s competitors.100

While poor quality of firearms could prove a serious obstacle to selling these weapons to Aboriginal people, their appearance also influenced Aboriginal customers’ response. Thus, James Bird at Carlton House noted in a letter to his superior George Sutherland at Edmonton House in 1796 that “I find our Guns this year very indifferent both in their Locks & Stocks those are in general a dark red and of course not much fancyed by the Indians: our Neighbours Guns far surpass them in appearances.”101

The quality of these early firearms, while still fluctuating, was apparently eventually raised to a level acceptable to Aboriginal customers, because these weapons became increasingly popular in the western Plains. According to William Walker, in charge of Manchester House in March 1790, the Blackfoot, Blood, and Pikani would travel far just to get an “English gun.” He also noted that his supply of such firearms was so low that he couldn’t satisfy the customers’ demands.102

The popularity of the firearms sold by the HBC seems to have become such that the competition eventually took to counterfeiting the HBC’s gun labels to increase their own sales. William Tomison noted that in March 1788, an Aboriginal man had brought in a gun 31/2 feet long, which had been brought from “Canada.” It was stamped with the same marks as the guns sold by the HBC. Tomison exchanged it for another gun and planned to send it to England as proof of counterfeiting undertaken by the competition.103 Usually Northwest guns sold by the North West Company were stamped with a sitting fox-like animal, facing right, enclosed in a circle. Hudson’s Bay Company guns, at least after 1821 but probably also earlier, carried a similar fox mark, but their animal faced left and was often enclosed in a frame in the shape of a tombstone.104 Furthermore, proofmarks and side plates identified the origin of weapons. As mentioned, Northwest guns usually had cast brass side plates in the shape of a sea serpent or dragon. The side plates used on French military and civilian weapons differed considerably from those on the Northwest guns.105

Manufacturing and Material Problems of Firearms

Early firearms such as the smoothbore muzzle-loading matchlock, wheel lock, and flintlock weapons have been much maligned as not only inaccurate and slow to reload but also prone to a wide variety of technical failures that could cause severe if not fatal injuries to the user. The traders of the Hudson’s Bay Company frequently faced problems such as lack of quality in manufacturing, as well as of the materials used in gun construction. Many post managers were earnestly concerned about these problems, since they could result in serious harm to their customers and drive them to trade with the competition. Thus, John Kipling at the HBC’s Gloucester House north of Lake Superior wrote in the fall of 1782: “I am sorry to observe the badness of our guns becomes a General Complaint among all the Indians.”106

While early firearms worked well in Europe, even in the damp British winters, their problems in North America may have been due in part to the metal parts not being able to withstand the extreme cold on Hudson Bay or the Northern Plains. Thus, HBC trader William Tomison at Manchester House on the lower North Saskatchewan River wrote in January 1787: “Men employed as yesterday, except Gilbert Laughton who was cleaning and repairing trading guns, some of the springs are so weak that Indians refuse to take them, as they will not give fire in cold Weather.”107 Eventually the springs of almost all the trade guns at Manchester House needed to be replaced before the weapons could be offered for sale.108

Problems with metal parts not functioning properly in extremely cold weather extended to items other than firearms. On several occasions Tomison complained about ice chisels and hatchets not working properly: “1793 January, 2nd Wednesday . . . smith & 1 man making hinges for Doors out of bad Ice Chizzels which Indians has refused and gone without and would not take them for nothing by sending such bad articles to his part of the Country is a means to diminish the Trade in the [illegible] of promoting it.”109 Tomison observed further: “Smith and 1 man making awl blades out of what was sent up for beaver Hooks but unfit for that purpose.”110

According to Louis Bird, Omushkego-Cree traditions also frequently mention the malfunctioning of firearms’ metal parts in the cold.111

During the seventeenth and early eighteenth century many Europeans believed that places of similar latitude had a similar climate, and that therefore metal parts manufactured in England should function properly on Hudson Bay. However, the continental climate of North America lacks the climatic moderation brought to Britain by the Gulf Stream. In addition, from roughly 1450 to 1850 the “Little Ice Age” affected northern North America and parts of Europe. During this time the mean summer position of the arctic front was farther south, placing Churchill and York Factory in the arctic climatic region. After 1760 the climate warmed, moving the line of the arctic front north. This placed York Factory but not Churchill in the boreal forest climatic region, where even from 1930 to 1960 the average year-round temperature was still only minus 7.3°C.112 Notwithstanding British perceptions that climate at the same latitude should be the same, fur traders like Alexander Mackenzie, who had years of exposure to the northern North American environment and the climate observations of Aboriginal people, clearly recognized the effect the vast open waters of Hudson Bay and the prevailing north winds had on the country’s climate, leading to much longer and colder winters in North America than in areas of the same latitude in Europe.113

Technical liabilities sometimes extended to large gun parts that could not be replaced easily, such as the breech. Thus, in November 1795 several Pikani-Blackfoot returned their newly acquired firearms to Edmonton House as useless. William Tomison, then in charge of that post, urgently pointed out to his superiors the flaws of the firearms the HBC was selling: “My reason for sending for the Smiths’ tools is by reason of the badness of Guns want of Nails fire steels etc., many of the Guns the Indians has brought back that they had in Credit some of which has not been more than once fired out of, being split two Inches from the Britchs [breech], several Indians were disabled last season by their hands being shot away this with other circumstances will reduce the Trade very much.”114

While en route from Cumberland House to the east end of Lake Athabasca, Peter Fidler made a similar observation: “The Indian burst 6 Inches from the Muzzle of his gun in firing at Swans.”115 It is impossible to tell whether these accidents were caused by inferior manufacturing quality of the weapons or by improper use, such as overloading the gun or neglecting to clean the barrel, which would result in powder residue from the main charge eventually clogging up the gun barrel. This clogging made reloading difficult and hazardous because the weapon might explode when the barrel was too clogged. To be as safe as possible, black-powder firearms had to be cleaned thoroughly after each use.

It is important to take into consideration that Aboriginal people acquired the skills to handle European weapons, as with archery, in a gradual learning curve. However, mistakes in handling firearms could quickly lead to serious injury or death, which was rarely the case with archery equipment. Robert Jefferson, observing mounted Plains Cree bison hunters using firearms in the later nineteenth century, described such accidents:

The guns, as discharged, are loaded again while racing:—a measure of powder poured into the muzzle haphazard, next a bullet rolled down the barrel from a store kept in the mouth, with a cap from a little circular arrangement on which they are stuck—and the hunter is ready for the next shot; no wads or paper or anything to keep each part of the load in its place. Of course the gun barrel must be kept in a semi-upright position till it can be aimed and discharged at the same moment. Many were the hands maimed, fingers blown off and other mischances by guns bursting owing to the bullet sticking in a dirty barrel.116

Problems with gun parts and metal tools not functioning properly likely reflect European misconceptions about the North American climate and the level of European metal technology at the time, rather than inferior workmanship per se. In the long run, manufacturing deficiencies and material problems did not prevent Aboriginal people from using firearms, but to be of advantage to them, firearms had to perform at least as well as their traditional weapons. Jefferson’s account makes this clear, because during the same bison hunt he also observed some Plains Cree hunters using bows and arrows with just as much success as other hunters used their guns.

It is important to put views about the impact of firearms on Aboriginal people into cultural and historical context. The presence of firearms and metal weapons alone is not sufficient to explain changes or variations in Aboriginal hunting methods and subsistence patterns, or in their combat methods and military relations. Aboriginal people adapted these European weapons to their own needs, often lacking awareness of, or deliberately disregarding, the precepts and safety measures that trained European users considered essential. To make their firearms fit their needs, Aboriginal people often subjected them to conditions and modifications these weapons were not built for, but which they often endured nonetheless. Aboriginal people also used their firearms differently from Europeans, especially in big game hunting and combat. In order to illuminate these differences in firearms usage, the following chapters will compare the practical applications of weapons use among Aboriginal peoples, beginning with a comparison of gunshot wounds and injuries caused by arrows.