Archery and Firearms in Aboriginal Beliefs

Fur trader Alexander Henry the Younger observed about Blackfoot people in the early 1800s: “A Gun which they [Pikani warriors] carry in their Arms with a Powder horn and Shot pouch slung on their Backs are always considered a necessary appendage to the Full Dress of a young Slave [Pikani] Indian. The Bow and Quiver of arrows slung across the Back also are their constant companion at all times and seasons, excepting when sleeping or setting their Tents. It is then taken off and hung to a Pole of the Tent always within reach. But if occasion calls them abroad only for a few moments the Bow and Arrow must accompany them.”1

According to David Thompson, “the [Pikani] men are proud of being noticed and praised as good hunters, warriors and any other masculine accomplishments, and many of the young men [are] as fine dandies as they can make themselves.”2

These observations by Alexander Henry the Younger and David Thompson indicate the importance of archery gear and other weaponry in the dress code of Pikani men in the late 1700s and early 1800s. Archery symbolism was deeply embedded in Plains cultures and imbued with meaning beyond the functional aspects of the bow and arrow as a weapon. For example, to cut the umbilical cord of a newborn, Blackfoot people used an arrowhead, not a knife, to symbolically and practically sever the new life from the old, associating the arrow with the renewal of life and the recurrence of generations.3 The terms “bow,” “arrow,” and “quiver” were frequently part of personal names among the Blackfoot and other Plains peoples.4

The use of archery was deeply ingrained into Plains Indian gender roles. The proper use of a powerful bow required great physical strength. In early anthropological accounts, Crow, Hidatsa, and Cheyenne people expressed the view that no woman could live without a man who provided for her and defended her, using his bow. With some exceptions, most Plains peoples were said to have discouraged women from using archery gear.5 However, this idea may express more about late nineteenth and early twentieth-century Euro-American views on gender roles than about actual Aboriginal practices. So-called women’s work—packing and moving camp, hauling water and firewood, butchering bison or tanning hides—required just as much physical strength as archery. If Plains people commonly held such views, they may have been employed to help keep a male-dominated order of society in place, leaving some room for exceptions.

To be shot accurately, a bow and its arrows must correspond to the user’s size and strength. For this reason, bows for children were smaller and had lower draw weights than those for adults. Among Plains peoples, the ability to use an adult-strength bow with proficiency and ease could signify adulthood and masculinity. Therefore, when adolescent boys were able to shoot fairly accurately with a bow of higher draw weight, they may have considered themselves close to adulthood. The Hidatsa Wolf Chief described such an experience. When he was seventeen years old, he and his father traveling on horseback came upon a small herd of bison bulls. Wolf Chief suggested hunting them. His father agreed but recommended that Wolf Chief use a gun, thinking his son was not yet strong enough to use his bow properly. However, Wolf Chief refused the gun and insisted on using his bow and arrows. He galloped off over a ridge in pursuit of the bison and managed to kill a large adult bull with a single arrow. When his father caught up and saw the slain animal, he exclaimed: “You have done it just like a man!”6 This episode shows the importance of proficiency in archery and having the physical capability of using a bow of adult draw weight. Had Wolf Chief killed the bison with his gun, his father would certainly have been pleased, but because he did it with his bow and arrow, his father viewed this as the action of an adult hunter.7 Similarly, the Blackfoot Crooked Meat Strings related that when he was fifteen years old, he was not yet strong enough to kill adult buffalo with a bow and arrow. Therefore he used a gun until later in life, when he managed to kill fully grown bison with bows and arrows.8

Furthermore, according to the Lakota Runs-the-Enemy (Tok-kahin-hpe-ya): “The first thing that I remember is that my father made me a bow and arrow; it was a small bow and arrow, and made in proportion to my size, compared with the bows used in killing buffalo. . . . My father taught me how to use the bow and arrow, and also how to ride a horse, and soon it became natural for me to ride. I soon grew to be able to use the bow and arrow that my father used; with it I killed buffalo [my emphasis].”9

In contrast to Plateau cultures and Native peoples with Subarctic origins, for whom fishing and gathering were important activities along with hunting, evidence from Northern Plains peoples suggests that they tended to disdain eating fish and considered bison meat their most important and proper food. Because the bow and arrow was the principal weapon for mounted bison hunting, they considered killing adult buffalo with the bow and arrow as a prestigious sign of adulthood and masculinity.10

A Hidatsa girls’ song points to the connection the Hidatsa saw between the expert use of archery gear, masculinity, and adulthood. Young Hidatsa girls sang this song to mock their male age-mates when the boys left the village in the morning to go bird hunting:

Those boys are all alike!

Your bow is like a bent basket splint!

Your arrow is only fit to shoot into the air!

Poor boys, you have to go barefoot!11

With underlying sexual allusions, the girls compared the boys’ bows and arrows to thin, elastic willow twigs used in basketry, which the Hidatsa considered to be women’s work, and ridiculed their archery equipment as slack and powerless and the boys as childlike or even effeminate.

To be praised for powerful archery skills was flattering to boys and young men. In a Crow story told by the medicine woman Pretty Shield in the early 1930s, a young boy was lured into a magic world by the mysterious being Red Woman. Red Woman made the boy do her bidding by praising his archery skills as an expression of his masculinity and physical maturity.12 Adolescents and men could be very susceptible to such flattery. Similar to the bow of Ulysses in Homer’s Odyssey, a bow of such strength that only its owner could string it could be the mark of an exceptionally manly warrior.13

Materials and Decorations of Bows and Quivers as Status Symbols

Among Plains Indians, not only the strength of a bow and its proficient use but also the materials and decorations of the bow, arrows, quiver, and bow case held meaning relating to the social status and/or the spiritual powers of their owner. Plains peoples carried their arrows in a quiver, while an oblong tubular container, the bow case, contained the unstrung bow. Both containers were attached to a long carrying strap. Such quiver–bow case combinations and the various ways of carrying them were well adapted to mounted use.14

In the 1830s George Catlin observed that Mandan men regarded their personal appearance very highly, and on special occasions they wore elegant clothing and richly ornamented archery equipment, including elaborately decorated quivers of mountain lion skin or otter fur.15 According to Wolf Chief, among the Mandan and Hidatsa such quivers were not meant for use on the hunt or in combat. He explained that Mandan and Hidatsa men used to wear special archery equipment on dress occasions, including public appearances, official visits, or courting.16 When they wanted to impress the women in their village, or when they went to visit their sweethearts, young Mandan and Hidatsa men wore quivers without a bow case. These were made of otter pelts or mountain lion skin, elaborately decorated with fringe and quill- or beadwork.17

When courting, a man wore an elaborately decorated quiver and carried his arrows with the fletchings at the bottom of the quiver, exposing the arrowheads.18 The arrows carried on such occasions were not blunt-headed, club-shaped arrows for bird hunting, or mere pointed shafts to kill rabbits or fish, but metal arrowheads with razor-sharp blades for big game hunting and combat, heated to a beautiful dark blue shine. Besides the arrows, such a quiver usually contained a short, sinew-backed bow of horn or antler, decorated with quillwork and horsehair and displaying its owner’s military honor marks.19

Mandan and Hidatsa bows often had an asymmetrical profile with a longer upper limb. When the unstrung bow was carried in a quiver, almost half its upper limb protruded from the opening. Even when the bow was in its case, the tip of the upper limb was still visible. Honor marks were displayed on the upper limb of such a bow. According to Wolf Chief, “The bow was always carried in the quiver, lower arm down. It would be ornamented [. . .] with porcupine bands and tassel or tassels of horsehair; and it would have on it any honour marks that the owner had the right to wear.”20

Many of Karl Bodmer’s paintings contain images of Northern Plains men wearing a bison robe or a blanket and carrying a bow and a few arrows in one hand. In this mode of carrying, the upper limb of the bow protruded from the robe or the blanket, showing the owner’s honor marks.21 Imitating warriors, small boys displayed “honor marks” on their bows by cutting small notches into the upper limbs of their bows, marking the number of birds they had killed.22

Sitting for a portrait, or later, for a photograph, was a dress occasion requiring the wearing of finery. Bodmer and Catlin portrayed many Aboriginal men with highly decorated bows and quivers. George Catlin also painted portraits of several sons of leading Plains Indian families, carrying archery gear.23 A large number of historic photographs, especially from the Southern Plains, show Aboriginal people wearing elaborate quiver and bow case combinations of otter or mountain lion fur, indicating that this tradition continued into the late nineteenth century.24 Because such images are so frequent and consistent in the work of different painters and photographers, it is likely that the archery items in those portraits were not always painters’ or photographers’ props, but belonged to the persons in the portraits themselves. If boys were portrayed carrying elaborate archery gear, perhaps it was their families’ way of documenting their high social standing and future warrior status.

Besides expressing social status through the display of elaborate archery gear, Aboriginal people in the Plains accorded spiritual meanings to certain bows, arrows, and quivers. The Peigan elder Reg Crowshoe listed bows and arrows among the society bundles used by certain men’s societies. These bundles were considered sacred and needed a transfer ceremony when they were handed over from the care of one society member to another.25 James Willard Schultz, who married into a Piegan community during the late nineteenth century, related a Blackfoot story of the making, capture, and recapture of a bow case made from albino otter skin.26 He claimed that this story was based on events that happened in the 1840s and published it under the title “Theft of the Sacred Otter Bow Case.”27 According to Schultz, Jemmy Jock Bird, son of HBC fur trader James Bird and a Cree woman, and Jemmy Jock’s brother-in-law Mad Wolf, went on a chase to recover a stolen sacred white otter bow case in the winter of 1846–47, traveling so far south that they reached Pueblo or ancient Anasazi buildings in the southwestern United States. However, according to historian John C. Jackson, the dates seem improbable because the journals of the Reverend Robert Rundle state that Jemmy Jock Bird was at Edmonton at the time.28 Jackson pointed out that Schultz came to the northwestern Plains in 1886, married a Piegan woman, and over the next sixty years produced Blackfeet/Blackfoot stories that were “an indecipherable mix of recalled truth and suspect fiction.”29

The aspect of this story that is important here is not its chronology but rather the spiritual significance attached to this quiver or bow case. In particular, a great deal of importance was accorded white buffalo. The Crow and Blackfoot, as well as the Swampy Cree, held ermine (white weasel) skins in similar regard.30 Considering the importance of white animals, it is interesting that an important Piegan leader bore the name “White Quiver” (Ksiks Unopachis, 1850–1931). Perhaps this name alludes to the white otter skin bow case mentioned by Schultz.31

Fig. 47. The Mandan Sih-Sä (Red Feather) wearing a highly decorated fur quiver and carrying an asymmetrical bow that has hair decoration on the upper limb. Karl Bodmer (Swiss, 1809–1893), Sih-Sä, Mandan Man, watercolor on paper. Joslyn Art Museum, Omaha, Nebraska. Gift of the Enron Art Foundation, 1986.49.385.

The Siksika elder Clifford Crane Bear related that Blackfoot people used to make a certain type of bow case for “special occasions.” When examining a Blackfoot cowhide quiver–bow case at the Glenbow Museum, he mentioned that it was similar to Blackfoot otter skin quivers–bow cases.32 The Smithsonian Institution holds a Piegan otter skin quiver–bow case that closely resembles the cowhide item in Calgary in its beadwork patterns and general layout.33 Otters played an important role in Blackfoot beliefs and were considered sacred. They were viewed as spiritually connected to water and rain, reflected in the existence of sacred otter tipis or the presence of otter skins in various religious bundles.

Clifford Crane Bear stated that the “otter skin–style” quiver of cowhide now in the Glenbow Museum was made for a staged “hunt” to entertain British royalty around 1905. Correspondingly, Indian agent George H. Gooderham reported that Prince Arthur, son of the Duke of Connaught, visited Gleichen, Alberta, in 1906 on his way to Japan. On that occasion the Siksika were to stage a steer hunt for the prince. A massive Blackfoot man and famous hunter by the name of Dying Young Man was said to have brought down a large steer with “a bow and arrow fired from his racing cayuse.”34 However, according to Clifford Crane Bear, the steer could not be killed by arrows and was eventually shot with a firearm. The quiver and bow case later came into the possession of the wealthy and influential Berry family in Alberta. Records from the Glenbow Museum indicate that the Glenbow Archives once held a photograph showing Hugh Berry as a child, wearing the quiver and bow case, which were later donated to the museum.35

Quivers and bow cases for ordinary use in hunting and combat were made from plain but durable materials such as brain-tanned leather or hides of bison, cattle, horses, deer, and elk. Sometimes boot or saddle leather produced by non-Aboriginal peoples was used, too.36 Louis Bird also mentioned that among the Omushkego-Cree, quivers for everyday use in hunting were often made from rather stiff tanned hides similar to rawhide with the hair left on. Their stiffness protected the arrow shafts and their fletchings from being crushed by accident. The Omushkego-Cree considered quivers of soft-tanned leather, decorated with fringes or beadwork, as fancy items for wear on special occasions, and such quivers were rather rare.37 Among the Mistassini Cree, quivers were of moose or caribou hide. Sometimes Mistassini Cree hunters thrust their arrows through their belts instead of carrying them in a quiver.38 While several elaborately decorated Subarctic Athapaskan quivers made from brain-tanned leather survive in museum collections, so far I have been unable to locate a similar quiver of documented northern Cree provenance.

Archery Items as Regalia of Northern Plains Men’s Societies

A Plains Indian person could belong to one or more societies throughout the course of his or her life. These societies had specific functions vital to the community. Their members were organized into different ranks, from common members to “officers” and leaders. Specific paraphernalia identified each rank. Military societies were concerned with combat but also had internal policing functions. Among the agricultural peoples of the Upper Missouri and among some of the mobile bison hunters of the Plains, such as the Blackfoot, Arapaho, and Gros Ventre des Prairies, these societies were age-graded.39 For example, among the Blackfoot, a young boy joined the Bees, then the Mosquitoes, and would work his way through various other societies until in his middle age he became a member of the Brave Dogs, the Horns, or the Old Bulls, the most respected and most influential men’s societies.40 The Pigeons or Doves Society was one of the first or lowest-ranking societies within the Blackfoot age-graded society system that male adolescents had to pass. According to anthropologist Clark Wissler, it was founded in the early 1850s among the South Piegan.41 Eventually it spread to the North Piegan, Siksika, and Kainai. In the early twentieth century Blackfoot people related that a man named Change Camp founded this society.42 Pigeons appeared to Change Camp in a dream and taught him the songs, dances, and rules of this society. In his dream the birds called on Change Camp to gather all the boys and noninfluential, powerless people. If all these persons would unite and follow the advice of the pigeons, they would become a powerful and respected society.43

Every Blackfoot boy of approximately fifteen years of age or older could join. Applicants had to purchase society membership from current members when these purchased a membership in the next highest-ranking society. Plain bows and arrows and a quiver were part of the society regalia carried by every new member at the time of the membership transfer. During the transfer ceremony a young and unmarried woman, selected for her outstanding virtue, sang with the six best singers of the society and also carried a bow and arrows.44

After the transfer ceremony the new members stormed out of the gathering lodge and shot their blunt arrows at the ground or at any unfortunate dog they happened to find. During ceremonies, four special members designated as “yellow pigeons” painted their bodies yellow and wore only a breechcloth. They carried bows of chokecherry or serviceberry wood, arrows, and a quiver made from the yellow hide of a buffalo calf. When they sang, they used their bows and arrows as simple musical instruments, beating time on the strings of their strung bows with their arrow shafts, producing a low resounding tone.45

The members of the Doves Society participated in many kinds of organized mischief, playing tricks on people and bullying the wealthy and influential of the community. These tolerated their pranks, granting them a certain amount of fool’s license, stating that the members of the Pigeon Society were still young and immature and that their actions were good training for raids on enemy encampments.46

Pigeon Society archery equipment was mostly used to shoot at animals or people, to tease and bother them. To prevent serious injury, the bows could not be very powerful and the arrows had to be blunt. The Provincial Museum of Alberta in Edmonton holds five Pigeon Society archery sets from the Blood and the Siksika. Three of these appear to be of recent manufacture because they exhibit construction characteristics untypical of older Plains archery items. The three bows were made from a thin branch or sapling. Wood was removed on the belly side to reduce the limbs to proper thickness. However, the grip area was left at full diameter, forming a so-called riser. This design feature is reminiscent of modern Euro-American sporting bows. Older Plains bows normally had no riser.

The bowstrings were very thin and mostly made of commercial thread. Most of the arrows were made from rather crooked shafts with kinks and twists. The fletchings were much shorter than on conventional Plains arrows, and the vanes were left much longer than usual. Some of these arrows have crude stone points, but most shafts were whittled to an obtuse point. However, two of these five archery sets include bows similar to older plains bows and without a thick handle. The arrows with these bows have fairly straight shafts, but the fletchings are still different from more common Plains arrows.47

Three of these five archery sets were collected in 1965 or later. Their more “modern” design features suggest that while the knowledge of Plains Indian bow and arrow manufacture declined, the importance of the Pigeon society remained, and the cruder and simpler archery outfits used in its post–World War II activities were sufficient for the society’s purposes. Or perhaps the cruder workmanship was meant to reflect comical aspects of the purpose and occasion they were to be used in, similar to the concept of “clowns” or “contraries” in other Plains cultures, who were expected to do or say the reverse of what they meant.

The Blood Daniel Weasel Moccasin made at least three bows for the documentary film episode “Standing Alone,” about the life of the Blood elder and rancher Pete Standing Alone, filmed on the Blood Reserve in 1982. The bows were made for a mounted archery demonstration, showing three young men from the Blood community shooting arrows at a hay bale on the back of Pete Standing Alone’s pickup truck while galloping beside the vehicle. The film includes a brief sequence showing the bow maker thinning the bow limbs on the belly side by chopping off wood with a heavy hunting knife, leaving a thick handle in the center. This construction characteristic is very similar to the more recent Pigeon society bows at the Royal Alberta Museum discussed previously. Most arrows shown in the film resemble arrows of more recent manufacture, collected from the Blood as well.48

Stone arrowheads were part of the insignia of warrior societies, for example, among the Kit Fox Society of the Cheyenne.49 However, the making and use of lithic projectile points by nineteenth-century Plains Indians has been disputed. Many early ethnographic accounts state that Plains Indians had no recollection of the manufacture and the use of stone arrowheads, and writers have argued that lithic projectile points frequently found in the Plains belonged to ancient precontact cultures.

When asked about the provenance of these projectile points, the Crows Plenty Coups and Pretty Shield replied that they were made by mythical beings called “Little People.” Plenty Coups told Frank Bird Linderman in the early 1930s that in precontact times, arrowheads had been made from bone.50 Pretty Shield related that arrowheads of a reddish stone were the remnants of the burst bones of Red Woman, a monster from Crow mythology. She also stated that stone arrowheads found in the Plains always got lost somehow and that it was impossible to keep them for long.51 Linderman concluded from this that the Crows and most other Plains Indians he encountered in Montana had no traditions of the manufacture of lithic projectile points and certainly had not made them in postcontact times. However, according to Arapaho traditions, their culture heroes taught them how to make arrowheads and knives from bones and wooden bows using stone tools.52 Blood (Kainai) traditions state that Napi, or “Old Man,” the trickster, creator, and culture hero of the Blackfoot, taught the people how to make bows and arrows with flint points in order to hunt buffalo.53 Similar traditions existed among the Plains Cree, whose culture hero “Pointed Arrow” was said to have been the earliest human being. They believed that he had earned his name because he invented the bow and arrow and taught its use.54 Cheyenne people told George Bird Grinnell that their culture heroes had taught their ancestors how to make blades and arrowheads from stone. They had also taught them how to haft such blades and arrowheads and how to make and use bows and arrows. The culture hero Heammawihio told the Cheyenne that soon after they received these instructions, they would encounter other peoples who used similar weapons and tools, whom he had also instructed in weapons manufacture.55

The Cheyenne made and used stone arrowheads in the nineteenth century, and their knowledge of making them dated back to precontact times.56 They also described the tools necessary to make stone arrowheads. These included stone hammers or smaller hammer stones used to break large chunks of flint into smaller pieces to make arrowheads.57 Some Cheyenne believed that arrowheads found in the Plains came from the arrows of the thunderbird.58

Among those Aboriginal peoples with age-graded societies, such as the Blackfoot, bows and arrows figured more prominently in the societies for adolescents than in those for adults. By the time anthropologists began to collect information from Plains Indians, the bison herds had long since been destroyed and the warrior ethos had lost much in importance. Archery had also lost much of its prestige as a weapon for adults. However, boys still used bows and arrows as toys or to hunt small game. Among most Plains Indian peoples, individual warriors strove to increase their prestige and to win military honors. However, killing an opponent from a distance was not generally considered a deed of great valor.59 This may explain why firearms were even less common than bows as insignia of warrior societies. Bows and close-combat weapons such as clubs and thrusting spears more explicitly symbolized courage and bravery in battle and were thus more likely to become insignia of warrior societies.

Archery Items in Myths and Ceremonies

Archery gear figured prominently in the creation stories of several Plains peoples. The Awatixa, one of the three Hidatsa subgroups, named their creation myth after one of its central characters, “Sacred Arrow.” Charred Body, the culture hero of the Awatixa, lived in a village in the sky. He had the ability to transform himself into an arrow to travel between heaven and earth. From his home in the sky he brought thirteen young couples to earth. These beings also had the ability to transform themselves into arrows. They founded the thirteen clans of the Awatixa. The “arrows” in this myth held spiritual and healing powers.60

Buffalo Bird Woman told Gilbert Wilson a story about an arrow that spoke to the Hidatsa, telling them that it would always serve them well as long as they maintained it properly and oiled it regularly.61 When Hidatsa boys received arrows as gifts, adults told them that these arrows represented the culture hero Charred Body. Therefore, they were to be well maintained and kept sacred.62 A medicine bow was of importance in the Hidatsa grandmother myth. One of the sacred objects used in the corn ceremony was a wooden bow painted red. Although the bow used in the ceremony was made of wood, Wolf Chief explained that the bow in the grandmother myth was an elkhorn bow.63

The central event in Cheyenne spiritual life was the annual ceremony of the medicine lodge, also referred to as the Sun Dance. It was held to achieve the spiritual renewal of the entire creation. The Cheyenne installed a nest of branches at the top of the center pole of the medicine lodge, representing the nest of the thunderbird. The sacrifice made to the thunderbird on this occasion consisted of a bundle containing a digging stick and arrows.64 The digging stick stood for plant foods, such as prairie turnips, gathered mostly by the women. The arrow symbolized meat, gained by men in big game hunting.65 These items expressed a prayer for abundant food and represented the cooperation and equally valued contributions of men and women to the nourishment and well-being of the people.

The Red Woman story of the Crow expressed similar symbolism. In this story a monster pursued a boy-hero. While the boy used his medicine arrows to increase the distance from his pursuer, it was his mother’s digging stick that enabled him to cross a river to safety, ensuring the boy’s escape and rescue.66 The symbolism in this Crow story may have had a meaning similar to the sacrifices to the thunderbird among the Cheyenne. While men hunted and fought with bows and arrows, it was a woman’s simple digging stick that saved the day, a hint at the importance of women’s contributions to the subsistence of the people.

Bows and arrows were of importance in the ceremonial killing of bison. Several Sioux and Crow ceremonies required the fresh hide of a bison killed with a single arrow. If the arrow completely penetrated the animal’s body, causing an exit wound, the cadaver and the hide could not be used and a different animal was chosen.67 To be chosen as the hunter for such a task carried great prestige because it was public acknowledgment of exceptional hunting skills. At the same time it was also a tremendous responsibility, because the proper performance of the ceremony and thus the welfare of the entire people depended on the success of this hunt.68 Two Leggings related that the Crow Bull Shield was once chosen for this role and performed it successfully. He was so sure of himself that he took only two arrows along when he set out on this hunt.69

The central Mandan ceremony was the Okipa, a reenactment of the Mandan creation myth. It was held every summer and lasted four days. It was meant to secure the fertility of the bison herds and the general well-being of the people. This ceremony included the voluntary self- torture of Mandan men, who hung from the rafters of the ceremonial earth lodge on ropes tied to wooden skewers pushed through the skin and muscles of their chest or back. Their shields, quivers, bows, and arrows hung from other skewers pushed through their leg and arm muscles.70

Among the agricultural and matrilineal Mandans, women owned the fields, earth lodges, and most of the household items. A man’s weapons, most of all his bow, arrows, and shield, were the most important of his few possessions. Therefore, these items were part of the men’s rituals of the Okipa ceremony and were placed on the burial platforms of their deceased owners.71

Physical and Spiritual Protection from Projectiles

Plains warriors commonly believed that they could harness spiritual protective powers through rituals and amulets and thereby render themselves impervious to arrows and bullets. This belief was most closely connected to the use of shields. Shields were made from rawhide taken from the neck section of a bison bull. The French referred to rawhide made by Native Americans as “parfleche.” This term comes from the French parer, “to parry, or ward off,” and fleche, meaning “arrow.” It indicates Plains peoples’ use of rawhide as a form of armor or shield at the time the first French explorers met them in the late seventeenth century.72

Before horses arrived, shields were rather large, covering a warrior from chin to feet. Saukamappee related to David Thompson that in his youth in the 1730s, Cree, Assiniboine, Blackfoot, and Shoshone warriors used large shields covering them from feet to chin while fighting in close formations on foot.73 With the adaptation of mounted combat and firearms, shields decreased in size. While several surviving Northern Plains shields from the first half of the nineteenth century have a diameter of 60 centimeters or more, those from the later nineteenth century are noticeably smaller.

The importance of the physical protective capabilities of shields declined after the introduction of firearms because at close range rawhide could not stop musket balls. As a result, Aboriginal people increasingly emphasized the spiritual protective powers of their shields. Eventually the importance of a shield’s spiritual protective powers surpassed that of its physical protective capabilities. The Crow Two Leggings illustrated this fact when he stated that he carried a large round rawhide shield on his back on a war party during the 1860s or 1870s. It deflected an enemy arrow in battle and saved his life. In spite of this success, Two Leggings decided to use a smaller shield on his next war party because he thought the larger one too unwieldy. He stated that the size of a shield did not matter because its spiritual powers, not its thickness or diameter, determined the degree of protection it could offer.74

Amulets were considered another source of spiritual protection from projectiles. Often stone arrowheads were part of such amulets. Cheyenne warriors wore them around their necks or tied them to their hair, along with small leather bags containing their personal medicines composed of certain plant parts. These bags were usually tied to the hafting tang of the arrowhead. Such amulets were meant to secure a long life for their wearer. To the Cheyenne, stone symbolized endurance and constancy. By wearing such amulets they hoped to obtain these characteristics.75

Cheyenne people also believed that the feathers of certain birds could protect humans from projectiles. For instance, arrows or bullets supposedly could not hit a man wearing the feathers of the immature bald eagle (Haliaeetus leucocephalus) or the blue or duck hawk (Falco peregrinus).76 By wearing amulets or images of lizards, butterflies, or dragonflies, Cheyenne warriors hoped to gain these animals’ agility and speed to evade projectiles in battle.77 Amulets representing arrows or guns were thought to ward off projectiles.78

In the 1930s the Ojibwa leader William Berens of Berens River in northeastern Manitoba related a powerful dream he had to the anthropologist Irving A. Hallowell. In this dream, Berens survived a contest of powers with a spiritual being and was rewarded with a gift of protection from bullets if he should ever go to war. Because Berens never did so, even though he was offered a chance during World War I, he concluded that he did not need the blessing, and felt that he could tell about it:

I was walking along and came to a house [not a wigwam]. I went in. There was no furniture in the room I entered. All that I saw was a small boy in a red tuque [a knitted cap]. He said to me, “Oh, ho, so you’re here.” “Yes,” I replied, “I’m here.” This boy had a bow in his hand and two arrows. One was red and the other black. “Now that you’ve found me,” he said, “I’m going to find out how strong you are.” I knew that if he ever hit me that would be the end of me. But I went to the middle of the room, as he told me, and stood there. I filled my mind with the thought that he would not be able to kill me. I watched him closely and, as soon as the arrow left the bow, I dodged. I saw the arrow sticking in the floor. He had missed me. Then he fitted the other arrow to his bow. “I’ll hit you this time,” he said. But I set my mind just as strongly against it. I watched every move he made and he missed me again.

“It’s your turn now,” he said and handed me the bow. I picked up the two arrows and he went to the middle of the room. Then I noticed a strange thing. He seemed to be constantly moving yet staying in the same place. He was not standing on the floor either, but was about a foot above it. I knew that it was going to be hard to hit him. I let the black arrow go first and missed him. I made up my mind that I was going to hit him with the red arrow and I did. But it did not kill him. He took the bow from me, tied the arrows to it and laid it aside. “You have beaten me,” he said. I was very anxious to know who it was but I did not wish to ask. He knew what I was thinking, because he asked, “Do you know who you have shot? I am a fly . . . “ [smaller than a bulldog fly which is to be seen on flowers—but is constantly moving and does not stay still long]. [The boy went on to say that W.B. would never be shot and killed by a bullet unless the marksman could hit a spot as small as a fly.]79

This “duel” and the contestant’s use of “mind power” are reminiscent of the contests between Subarctic shamans. However, the red and black color duality of the arrows used in the duel resembles the sacred arrows of the Cheyenne, which were red and black. The spiritual protection from bullets as a reward may also point to connections or influences from the Plains.

Bows and Arrows as Grave Goods

Among Aboriginal peoples in the Plains, Subarctic, and Arctic, archery items became grave goods when they were placed next to their owner’s body upon burial. Writing in the late seventeenth century, the French military officer La Potherie noted that Aboriginal people on the shores of Hudson Bay burned the bodies of the deceased and then collected the bones and buried them in the ground, along with grave goods: “When the father or mother dies the children or nearest relatives burn the body. They wrap up the bones in the bark of trees and bury them in the ground. They build a tomb, surrounded with poles to which they tie tobacco for the spirit to smoke who will look after them in the other world, with bows and arrows to enable him to continue his hunting if he is a hunter.”80

During the first half of the eighteenth century Joseph Robson recorded in regard to the burial customs of the Swampy Cree:

When an Indian dies they usually bury all he possesses with him, because, they think he will want it in the other country, where, they say, their friends are making merry as often as they see an Aurora-borealis. The corpse being placed upon its hams, the grave is filled up and covered over with brush-wood, in which they put some tobacco; and near the grave is fixed a pole with a deer skin, or some other skin, at the top. This method of placing the corpse is no longer observed by the people who resort to the English factories; but the upland Indians still retain their ancient customs.81

Similar practices prevailed among the Inuit of northwestern Hudson Bay. In 1813 Captain Stirling of HMS Brazen, while escorting HBC ships into the bay, came upon the burial site of an Inuit man in the hills near the shore. Stirling and his officers discovered “the dead body of an Esquimaux: it was closely wrapt in skins, and laid in a sort of gully between two rocks, as if intended to be defended from the cold winds of the ocean: by the side of the corpse lay the bow and arrows, spears and harpoon of the deceased; together with a tin pot, containing a few beads and three or four English halfpence.”82

The funeral of the baptized Mi’kmaq leader Membertou in 1611 combined European and Aboriginal customs and ideas. There was a funeral procession with a large cross and drums. Membertou was buried under a cross, but his bow and arrows were hung from it.83

Among Plains peoples such as the Mandan, archery items were often part of men’s burials.84 The relatives of deceased Sioux leaders, medicine men, or warriors of rank, and also of male children from prominent families, often laid the deceased person’s archery equipment upon the burial platform to document their status.85 As a boy the Mormon settler E. N. Wilson, who had lived among the Eastern Shoshone during the late 1850s, witnessed the burial of a chief’s son who had been killed in an accident. Wilson related that the mourning family “killed three horses and buried them and his bow and arrows with him.”86

In the 1950s the mummified body of the Cheyenne leader High-Backed Wolf, who was killed on the North Platte in 1868, was exhibited with all his equipment in the House of Yesterday at Hastings, Nebraska (now the Hastings Museum of Natural History). His weapons included a bow and a supply of arrows, a stone-headed war club, an army camp knife, and a Henry repeating rifle.87 However, among the Cheyenne the families of deceased warriors often gave especially valuable items, such as quiver and bow case combinations of mountain lion skin, to a close friend of the deceased instead of placing them on the burial platform.88

Archery items used as grave goods during the early contact phase between Subarctic Aboriginal peoples and Euro-Americans on the East Coast and in the Hudson Bay Lowlands represented an Aboriginal man’s role as hunter, provider. and warrior. While this remained the case in the Plains until the reservation period, it changed in the Subarctic where firearms eventually superseded archery items in representing the role of the big game hunter and fighter.

Firearms in Aboriginal Beliefs

For Aboriginal people, the process of adapting European goods and weapons included placing them within a framework of their own cultural understanding and worldviews. These adaptive processes were not uniform, but they evolved within already existing cultural practices and patterns. For instance, Aboriginal people in the Central Subarctic were much concerned with individual hunting medicine. During the early nineteenth century the fur trader George Nelson observed some of these beliefs at work or obtained information on them from his Aboriginal or Métis guides. In his memoir, Nelson related information about an Iroquois hunter who believed he had been bewitched. He could not kill any animal with his gun until his Cree or Ojibwa wife cleaned his gun, along with the musket balls, by filling and washing it with lye overnight. After that, the hunter was said to never have missed a shot again.89 Another freeman told Nelson of a similar incident: “At last one day prowling in my Canoe I met 2 other free-men, who, after mutual enquiries &c, told me the same thing had happened to him and that an Indian told him to file off a small piece of the muzzle of his Gun and wash it well with water in which sweet-flag [prob. Acorus calamus, an arum] had been boiled, and killed after that as before. I laughed at the idea, but reflecting that it was an innocent experiment and could not offend the almighty, I tried, and the first animals I saw I immediately killed.”90

Nelson participated in a Cree shaking-tent ceremony and described some of the spirits that were said to have entered the lodge on this occasion: “The Sun enters—speaks very bad English at the offset, but by degrees comes to speak it very easily and fluently. He is Gun Smith and watchmaker, or at least he can repair them [my emphasis].”91 According to Nelson, a Cree man brought his defective gun to this ceremony where the sun spirit fixed it.92 During the ceremony, Nelson observed: “Some of them [the conjurers] to show their Power have had small sticks of the hardest wood (such as produces the wild Pear [Saskatoon berries, Amelanchier alnifolia] and of which the Indians make their arrows, and ram-rods, &c for Guns) about the size of a man’s finger, made as sharp pointed as possible, and dried, when they become in consequence nearly as dangerous as iron or bayonets.”93

The shamans lay down upon the sharp pointed ends of eighteen to twenty-four of these sticks during the ceremony, but afterward no marks of injuries would appear.94 Cree peoples’ choice of the same wood for the manufacture of arrow shafts and ramrods indicates another connection between their own projectile weapons and European firearms.

In 1783 George Sutherland at the HBC’s Albany post observed the funeral of the Cree leader Questach, who had been the “captain” of the post’s goose hunters: “James Salter made a Coffin for Captn Questach. . . . Myself with all the Indians on the plantation attended the remains of old Captn Questach to a woodin tomb built in a very permanent manner, he was buried with more solemnity and ceremony than ever I saw upon like occasion; Gave him the colour half mast high; In the evening the Indians made a grand feast upon the occasion and kept firing guns all night [my emphasis].”95

Similarly, Andrew Graham recorded that “no sooner is the breath out of the body than one of the men fire off a gun in the tent, in order to deter the spirit, or soul of the deceased from coming again and troubling them.”96

In their mix of European and Aboriginal traditions, these funeral ceremonies were remarkably similar to the funeral of the Mi’kmaq leader Membertou, more than a century and a half earlier. Apparently the firing of guns held a special significance to the Cree that was not well understood by the European fur traders at the post. Almost thirty years later Peter Fidler made a similar observation among Déné people:

Last night 2 Shots & this Night 5 Shots were fired at the Canadian House at between 9 & 10 o’clock at Night. There is an Indian there in a dying state & this is done by his Friends who attend him to keep away the Messenger of Death—according to their wonted custom.

[On the next day] The ailing Jepewyan nearly dead, & this morning by his own request they hawled him about 1 mile off to die.97

Both events involved Subarctic Aboriginal people. However, it is not clear if the firing of guns on this occasion held the same meaning for the Chipewyan as it did to the Cree in the funeral at Albany in 1783. The Cree fired their weapons at the funeral, whereas Fidler portrayed the actions of the Chipewyan as an attempt to help keep an ailing person alive. Whatever their reasons may have been, the actions of the Cree and Chipewyan indicate that by the late eighteenth century they had incorporated firearms into their spiritual beliefs and practices. Firearms were even connected to powerful spiritual beings, central to the beliefs of Aboriginal peoples in the Subarctic and Plains.

Guns, Arrows, Thunderbirds, and Underwater Panthers

The beliefs of many Aboriginal groups of the Algonquian and Siouan language families contained concepts of the thunderbird. This entity was seen as a powerful force inherent in many aspects of the natural world, manifesting itself in such phenomena as thunderstorms and lightning strikes, sometimes appearing in the shape of a large bird. This force was associated with success in war and in medicine and healing.98 If the explosive discharge of a firearm—the muzzle flash, noise, and smoke but mostly the tremendous destruction upon impact of the projectile—were interpreted as manifestations of the power of the thunderbird, whoever operated a firearm partook in an activity that was permeated by spiritual importance by harnessing that power. If those attacked with firearms held similar beliefs, they therefore considered themselves under attack by powerful enemies who could marshal immense spiritual powers against them. While this belief instilled fear and panic in those attacked, it also instilled great confidence in the attackers.99 The Omushkego-Cree elder Louis Bird related:

There was something that I forgot to mention about the results of the firearm. In the Mushkego country some of our ancestors, when they have seen the gun, it has given them the idea how to use it in their own shaman power. And there is a story, it’s about some miteos’ personal practice. [Some] shamans were able to use the firearm, or a gun without reloading. They were able, supposedly, to keep aiming and cause it to fire as if it has been reloaded. This they have done during the time when other tribes used to come and attack them unexpectedly. And those who had shaman power, sometimes they would defend their families by using this, just the gun itself, but without any gunpowder and the slugs. And were able to defend their family. So for that reason the gun, the firearm has given a strength to the First Nation and it has given some additional ideas because of the firearm. And there’s a story about the greater shaman [who had] an idea how to harness his dream quest, having the thunder being as his helper, and was able to use a similar object as a gun barrel to guide the lightning bolt to kill his enemies. So the gun had brought an extra idea amongst the First Nation in Omushkego land. There is a story about this. The story is very fascinating and it’s very powerful. They called it “The Omushkego Who Fought With Thunderbolt.” So, there goes. Shows us how powerful an influence this firearm can be. And there were some who have tried [something] similar. Those who pretend to be a shaman, trying to use only the barrel to fire the gun, sometimes it did not actually work, they just tricked [pretended] to use it.100

Besides oral testimony, material evidence also suggests Aboriginal beliefs in a connection between firearms and thunderbirds. For instance, several shot pouches and hunting bags collected from Algonquian-speaking Eastern Woodland and Subarctic peoples during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century were embroidered with thunderbird motifs.101 Such bags or pouches held musket balls or shot, as well as gunflints, gun worms, and other items necessary to keep a muzzle-loading firearm in working order.

The connections Aboriginal people saw between thunderbirds and firearms may have been based on precontact traditions of similar connections between thunderbirds and projectile weapons, especially arrows. For example, before shooting an arrow, Plains Indians used to point it skyward after the arrow was placed on the bowstring. Then the bow was drawn and brought down in a quick and fluid motion. When the arrow pointed at the target, it was released. Besides practical considerations of clearing the hands of horses’ reins, fringes, or loose shirt sleeves that could get in the way and interfere with shooting, it may also have expressed a connection of arrows to the sky and thus to the thunderbird.102

The Cheyenne placed arrows as offerings in the nest of the thunderbird on the center pole of the Sun Dance lodge, but Cheyenne also recognized other connections between arrows and the thunderbird. For example, they believed that if they ever forgot how to make arrows, the thunderbird would instruct them again.103 Gilbert Wilson noted that the Hidatsa saw a connection between their culture hero Burnt Arrow and a special kind of arrow with just one long split feather wrapped in a spiral around the back end of the shaft for fletching. Hidatsa bow maker Henry Wolf Chief stated:

An arrow with a spiral feather was called Isu-dumite, or wing-twisted around. We did not say “arrow feather” but “arrow wing.” . . . Spiral feathered arrows, such as I just described above, were the first kind of feathered arrows a boy shot with. We would say to the boy, “This is Adapozis, Burnt Arrow and should fly straight. Adapozis was a Thunderbird [my emphasis]. You should keep this arrow sacred, and pray to it.” . . .

There were a few men in the tribe who always carried two of these spiral-feathered arrows in their quivers. These arrows they would not ordinarily use; but when they came close to the enemy, a man having these spiral arrows would take them out and pray to them, “Kill this enemy!” And he would shoot at the enemy with one of these arrows. In my time I never saw this custom used; but I have heard of it as being in our tribe in former days.104

According to Wolf Chief, the three wavy grooves cut into arrow shafts represented the Hidatsa culture hero Burnt Arrow or Charred Body. Burnt Arrow was said to have referred to these grooves as lightning, and he taught the Hidatsa to groove their arrow shafts.105 Prince Maximilian noted that to the Mandan, spiral or wavy grooves on their arrow shafts represented lightning.106 Cutting straight or wavy grooves into arrow shafts and associating them with lightning was widespread among Plains peoples, whereas shaft grooves were much less frequently used among Aboriginal peoples in the Eastern Woodlands, Subarctic, or Plateau. The practice was apparently absent on the Northwest Coast and among the Inuit.107

The Big Bird medicine bundle of the Mandan included arrow-making ceremonies and rights and was connected to thunderbird concepts. The Big Bird myth contains elements of the struggle between snakes, both mythical and real, and thunderbirds as the leaders of all the large birds like eagles, hawks, and ravens. According to this myth, both thunderbirds and mythical snakes, some of whom were believed to live in the water and have horns, could shoot lightning.108 The two main protagonists of this myth, Black Medicine and his younger brother, the sons of the Mandan leader Big Bird, were transformed into thunderbird eagles through hatching: “On each of the two eggs there was a straight and a zigzagged line representing the lightning, for sometimes the flashes are straight, other times zigzagged.”109 Similar lines appear as straight and zigzagged grooves on numerous Plains arrow shafts, pointing out the connection between arrows and thunderbirds. However, Mandan people believed that not only thunderbirds but also snakes possessed the supernatural power of producing lightning.110

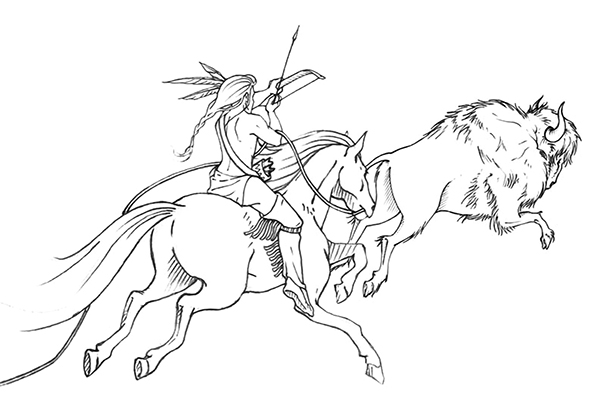

Fig. 48. Mounted bison hunter showing the Plains Indian method of pointing the arrow upward before the bow was fully drawn and the arrow was brought down on the target. Note the long bridle trailing on the ground to give the hunter an opportunity to recapture the horse if thrown off. The Lakota archers in Figures 1 and 2 hold their bows and arrows in a very similar way, although they are on foot. Drawing by Janet LaFrance.

Such beliefs may be reflected in the use of snakeskin on bows in the Northern Plains and the Plateau region. For example, among the Oglala Lakota in the second half of the nineteenth century, there existed a Sacred Bow Society whose leading officers wielded a bow lance in battle to which, among other items, rattlesnake skins were attached.111

Snakeskins also appeared as bow backings. When traveling through the Columbia Plateau in the early nineteenth century, David Thompson noted that local Aboriginal people used rattlesnake skins to cover the sinew backings of their bows.112 Reginald Laubin examined an asymmetrical sinew-backed Hidatsa bow, possibly of elkhorn, the back of which was covered with a snakeskin.113 The Crow Two Leggings also was related to have made a hickory bow with a snakeskin on its back.114 Some sinew-backed bows, mostly of horn or antler, have quillwork decorations in alternating light and dark bands at the upper end. Because these are similar in appearance to the dark- and light-colored bands on the tail of a rattlesnake, they may represent a connection between the bow and the snake.115

Most of the snakeskin-covered bows I have examined were covered with the skin of rattlesnakes (Crotalus spp.).116 However, at least three bows, possibly all Blackfoot, are covered with the skins of garter snakes (Thamnophis radix). These animals have three bright yellow and white stripes on the back and sides, against a dark background. This striking contrast is reminiscent of lightning against the background of dark clouds.117 Another connection between snakes and thunder may have been based upon both being signs of coming summer, heralded by the first thunder of the year and the emergence of snakes from hibernation.

While the concept of thunderbirds was widely held in the Eastern Woodlands, Subarctic, and Great Plains, Algonquian peoples of the Subarctic and the Great Lakes area, and to some extent the Plains, also believed in the spiritual powers of beings like the underwater panther or similar feline-serpentine water beings like the “great water lynx” and the “sea serpent.” For example, West Main Cree legends included powerful underwater creatures living in lakes and streams.118

While both groups of spiritual beings were important for hunting, medicine, and warfare, the great water lynxes, or underwater panthers, were often perceived as the antagonists of the thunderbirds. Water lynxes and sea serpents were associated with water or underground spaces, usually inimical to humans. They were considered to be eternally at war with the thunderbirds, who in some Aboriginal cultures were considered protectors of humanity and were associated with the upper air and sky.119

To Central Subarctic Aboriginal people, firearms combined associations of powers attributed to these groups of beings. Archaeologists William Fox and C. S. Reid claimed a connection between the mythological being known as the underwater panther or “Mishipizhu,” Algonquian hunting medicine, and the brass dragon side plates on trade guns.120

Cree and Ojibwa people believed that through the practice of hunting medicine, they were able to influence game animals through the production and manipulation of images. Among the Mistassini Cree, the decoration of hunting equipment such as guns, gun cases, and ammunition pouches expressed respect to the prey, but was also meant to ensure that the “spirit” of the object would fulfill its task in the hunt.121

According to Ojibwa beliefs, underwater panthers had horns like a bison, brassy scales on their bodies, and metal tails.122 Other Algonquian peoples, for example, the Menomini, also saw a connection between such underwater beings and metallic scales on their bodies and tails.123 Therefore it is possible that the side plates on trade guns reminded Cree and Ojibwa of these powerful beings because they were cast in the shape of a sea serpent or dragon and were made from brass.

Several fragments of dragon side plates found near York Factory show evidence of intentional damage caused by attempts to wrench them off their guns and to remove the dragon’s head and/or tail. According to Ojibwa legends, the underwater panther’s head and tail were considered the most powerful and dangerous parts of the creature. When a trade gun was discarded, possibly after a burst barrel or similar accident, the ritual destruction of the dragon side plate may have taken place to “kill” the gun’s spirit, due to what Aboriginal hunters may have viewed as a broken relationship between a hunter and a spiritual being.124 The connection between underwater panthers and firearms is further confirmed by images of these beings embroidered onto hunting pouches and gunstock clubs.125

Fig. 49. Dragon side plates were mounted opposite the lock system on trade guns, to hold it in place on the gun. Drawing by Margaret Anne Lindsay.

According to Cree and Ojibwa views, in the struggle between the underwater beings and the thunderbirds, there was a basic alliance between humans and thunderbirds. Plains Cree elder Stan Cuthand related as part of a Cree creation story that in mythical times, ten heroic men married ten thunderbird women. This made humans relatives of thunderbirds.126 The underwater panthers, lynxes, and sea serpents, on the other hand, were enemies of the thunderbirds and by extension of humankind, at least according to Stan Cuthand.127 Therefore, associating firearms with these beings came naturally to Aboriginal people because firearms, besides being hunting weapons, were used to a large extent in warfare against fellow human beings. In this way the destructive powers of the underwater beings and the thunderbirds could be harnessed through the use of a firearm.

While images of underwater panthers are more frequently found on objects from the Woodlands than from the Plains, perhaps some of these beliefs extended to Plains cultures, too. For example, there is at least one historic photograph showing a Blackfoot man wearing a breastplate made of six dragon side plates.128 There are also examples of trade guns from the Plains heavily decorated with brass tacks, which may point to Aboriginal people there seeing a connection between firearms and underwater beings.129

Hinting at the spiritual significance of serpentine motifs and brass decorations, the Hudson’s Bay Company trader Isaac Cowie had this to say about trade guns decorated by Native people in the Canadian Plains in the second half of the nineteenth century: “The wooden stocks of these guns ran out under the barrel to within an inch or so of the muzzle. The groove for the ramrod had brass clasps at intervals and two brazen serpents decorated the grip of the stock. To these ‘Brummagem’ decorations the Indians added others of their own device, in brass-headed tacks, without which the weapon seemed unconsecrated in their eyes.”130

Subarctic Aboriginal people focused on individual big game hunting medicine, and during the nineteenth century they used their guns mainly for big game hunting and less for warfare, because by this time, warfare in the Central Subarctic may have diminished.131 In contrast, in the Plains, hunting was to a large extent a communal affair, and firearms were mainly used for combat. The dragon side plates in the Blackfoot breastplate could have come from captured enemy trade guns. The same warrior also held a repeating rifle, showing that muzzle-loading trade guns were becoming obsolete by the time the picture was taken. While the Blackfoot had access to modern firearms through trade with Americans, the Plains Cree, who during the late nineteenth century were frequently at war with the Blackfoot and who were mainly HBC customers, still used muzzle-loading trade guns with dragon side plates. Such guns were the only kind of long gun the HBC sold, as the company refused to sell repeating firearms to Aboriginal people. Keeping this in mind, as well as the importance the Blackfoot placed on the capture of enemy weapons, especially firearms, it is possible that this breastplate was made from the dragon side plates of captured enemy guns.

Robert Hall pointed out another example of the deep spiritual connotations that Aboriginal people in the Great Plains and southwestern Great Lakes region attached to traditional distance weapons and later to firearms. The sacred associations of tobacco for Aboriginal people are well documented. Similar associations existed for varieties of kinnikinnick, a preparation made from dried leaves (Arctostaphylos, especially A. uva-ursi, bearberry), bark, and wood shavings, sometimes mixed with tobacco.132 Among the Menomini, Osage, and Hidatsa, some varieties were made from dogwood bark and wood scrapings that were a by-product of arrow manufacture. Later, they used such kinnikinnick as gun wadding to seat a musket ball firmly in the barrel of a muzzle-loading firearm. Among the Osage, Cheyenne, and other Plains peoples, arrows symbolized the renewal of life through abundance of food gained through hunting, and they symbolized safety through protection and defense in war. Thus, both arrows and kinnikinnick were connected to concepts of eternity. Through the use of kinnikinnick as gun wadding, similar concepts may have been transferred to the projectiles and the use of firearms.133

Another spiritual concept among Algonquian-speaking peoples of the boreal forest and the Plains was the idea of increasing one’s spiritual strength by killing and absorbing the life force of others. From Saukamappee’s account, David Thompson understood that the Parkland Cree and the Pikani believed that slain enemies would become the slaves of their slayer’s deceased relatives in the afterlife if the slayers or their relatives kept the scalps of the slain.134 However, for this to work out properly, warriors needed to determine precisely who had killed which opponent. With the use of firearms in combat, this became difficult, since musket balls, unlike arrows, did not carry personal marks of ownership. Therefore, new ways to attribute warriors’ claims had to be determined. For example, Saukamappee related how after a battle, he and his fellow warriors were allowed to wear a special face paint to distinguish them from other victorious warriors, as those who had been the first ones to use guns against the Shoshone and thus had brought about victory.135

Assuming that Thompson and other fur traders understood correctly the concept of absorbing the life force, it seems that this concept was eventually given up among Algonquian-speaking people of the Plains during the nineteenth century, since most anthropological accounts collected in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries do not mention it. This may indicate an adjustment or change in Aboriginal spiritual concepts caused by the introduction of firearms and their “impersonal” bullets.

Aboriginal people on the East Coast and in the Hudson Bay Lowlands encountered firearms almost a century before Aboriginal peoples on the Northern Plains. Their longer exposure to guns and the increasing emphasis on individual big game hunting gave Central Subarctic Aboriginal peoples more time and incentive to develop deeper spiritual meanings and associations with regard to firearms while at the same time slowly disassociating these meanings from archery equipment and other traditional weaponry.

In the Plains, by contrast, firearms were added and incorporated into the Aboriginal arsenal without displacing archery. For the bison-hunting peoples, archery gear remained necessary until the reservation period, and it continued to hold its spiritual significance while spiritual contexts for firearms began to emerge as well. In both regions, Aboriginal people developed dependable distance weapons from locally available materials, in spite of the limitations in available raw materials in their homelands. When European technologies in the form of metal arrowheads and firearms became available, they integrated these into their belief systems and their hunting and combat methods. The following chapters will focus on the practical applications of archery and firearms, beginning with an examination of Aboriginal peoples’ use of archery and firearms in hunting.