DUMPLING AND TREACLE

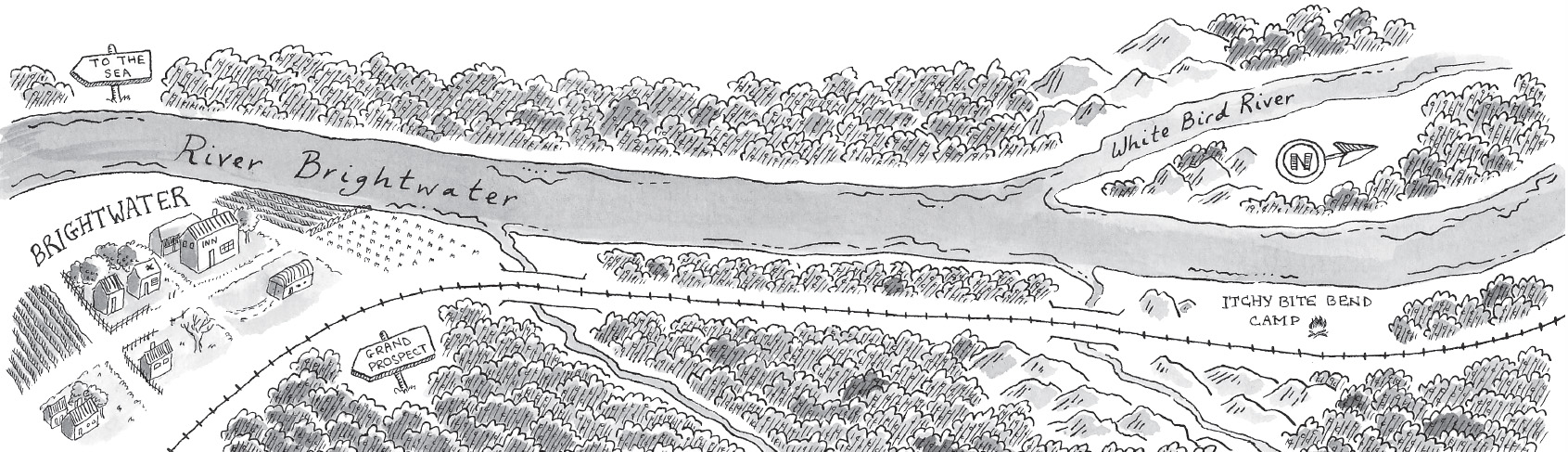

They reached Beckett’s village in the middle of the afternoon. Joe had never seen such a sad place. Most of the buildings were deserted and their roofs had fallen in. Beckett said that the people who used to live in them had given up and moved to Grand Prospect because it was too hard to make a living so far from anywhere. Weeds grew up around the door of the smithy, and the paddocks along the riverbank had been abandoned to thistles. The inn looked solid enough, but the roof of Beckett’s cottage was covered in patches.

Beckett’s mother ran to meet him with his five younger brothers and sisters. They all exclaimed and hugged. He gave his mother the coins he’d saved by doing odd jobs in Grand Prospect, and some soap and cooking oil he’d brought for her, and she hugged him again, and told him he’d grown and how his voice sounded all manly, which made his ears turn crimson.

Beckett introduced everyone, then he asked his brothers and sisters to look after Plodder.

“We’re going to have a talk with Mr Arbuckle.”

Mr Arbuckle was the village baker, and also the innkeeper and the ferryman who rowed hunters across the Brightwater River. There was no one in the inn, and there was nothing in the bakehouse but flies. They found him out the back, splitting logs, his face scarlet and sweat dripping off the end of his bulgy nose. When Beckett asked him to lend his donkeys, he just snorted.

“We’ll pay you double,” Sal offered recklessly. “Double whatever the rate is for donkeys, when we return them.”

Mr Arbuckle pulled out a hanky and mopped his neck. “You won’t return,” he said. “Few people have crossed those bare steeps where desolation stalks.”

“Stalks,” said Carrot, eyeing him from a log.

“Shh!” Sal was sucking on the end of her plait—a sure sign that she was anxious. But Beckett didn’t look bothered; he gently persuaded Mr Arbuckle to rest in the shade of a tree, and he squatted in front of him.

“Mr Arbuckle, sir. You are the leader of this village and a wise man. This competition is to find a way through the mountains between Grand Prospect and New Coalhaven, so folks can get to New Coalhaven more easily. First, just a horse track, but then—a railway! Now, I want you to imagine something …”

Beckett spoke in a way that made everyone want to listen. Mr Arbuckle leaned back against the tree trunk and fanned himself with his hat.

“Sir, I want you to imagine that the winning route comes through this village. First, surveyors pass through here, and engineers. They stay in your inn. Next up, the railway builders arrive. They need to be fed and watered. Then trains come through. Everyone buys your famous pies. You get your Daily Bugle on the day it’s printed, instead of a week late. You grow rich.” He paused. Mr Arbuckle was listening closely. “You can afford to pay someone to cut your firewood. Your back stops hurting. The village grows. We become somewhere. We need a mayor—” He paused dramatically. “We elect you, Mr Arbuckle!”

Joe was impressed. Beckett had thought a lot about what having a railway station would mean to his village, and Mr Arbuckle seemed to believe every word—for a minute. Then he noticed Humph, who was trying to do a somersault, bottom up and one leg waving in the air, and he became cross. “That’s ridiculous. How do you imagine that you children could ever win? I’ve read about this competition in the Daily Bugle. There’s a team of scientists who’ve entered. And Sir Monty Whatsit—he’s famous. And Cody Cole, that professional explorer. And you think you lot can beat them? Ridiculous.”

But Beckett hadn’t finished. “Sir, they may not be fully grown, but the Santanders have been trained by their famous explorer parents, and they all have special skills. The competition is to produce a route and also to make a map. Like this.”

He smoothed out Francie’s map. Mr Arbuckle glanced at it, then he peered more closely. There was silence, then he let out his breath in a long whistle.

“Who drew this? When?” He looked at them all in turn.

“Francie drew this yesterday, sir,” said Sal.

“Extraordinary.” He looked at Francie, who was busy sketching him, and at Joe and Sal, sitting cross-legged on the ground. “Quite extra-ordinary.” His finger traced the road between Grand Prospect and the village.

Then Francie did something she’d never done before. She carefully tore out the page she’d been working on and held it out for Mr Arbuckle to take. It was a terrific portrait, just how he must have looked about twenty years before, but with a normal-shaped nose.

He blinked. “I say.” He swallowed. “I say, I say!” He fanned his face with his hat. “My goodness, what a likeness.” He hesitated, his voice uncertain, almost apologetic. “But I need my donkeys. I use them every day.”

Beckett had the answer for everything. “We will leave you our horse and dray to use while we’re away, sir. It’s a fair exchange and I promise you won’t regret it.”

That night they stretched out in a row under the apricot tree in Beckett’s garden. As soon as Humph was asleep, Joe called out quietly, “Beckett! Beckett? Who does Plodder actually belong to?”

Beckett cleared his throat. “Um … I’ve no idea.”

“What?” Joe and Sal exclaimed together.

“Well I hadn’t eaten in ages. I was watching the preparations in the square and wondering how to lay my hands on a loaf of bread, when this man asks can I drive a horse and dray? I says, course I can, since I was knee-high, and he says, take this horse to the station to meet the last expedition and there’s a free feed for you. The driver had got into a fight and his nose was pouring blood. But the bleeding man was just the driver. Plodder wasn’t his horse. I’ve no idea who owns him. I just picked you up and took you to the town square and now here we are.”

“D’you mean we’ve stolen him?” asked Sal.

“Borrowed,” said Joe, “because we really, really needed the donkeys. Twenty-five days to go.”

*

Dumpling was a honey-coloured female and Treacle was a black male donkey. They were fully grown but seemed very small. The Santanders looked at the mountain of equipment and essential supplies they’d unloaded from the dray, and at the four harvesting baskets Beckett had borrowed from his mother, which the donkeys would carry as panniers.

They started to make piles. Ma’s clothes, her darning bag, and the lesson books she used to teach them latin, history and astronomy were easy choices for the “leave” pile, but everything else seemed equally essential.

“So now what?” said Joe. The “take” pile was still a ten-donkey load.

“What now?” said Carrot.

Beckett laughed and picked up Simpson’s Grammar Explained. “Did you teach that bird to talk?”

Joe held out a piece of unripe apricot to Carrot. “Ma rescued her from a schoolroom. Carrot spent years listening to Miss Wilton-Clark, the world’s bossiest teacher.”

“I’m glad I don’t ever have to go to school again.” Beckett dumped the grammar with the other books on the back of the cart.

They tried packing the other way: essential stuff first, then what they still had room for. The food, the cooking pot and the billy for heating water fitted into two baskets. The surveying and map-making equipment, the groundsheets, the bucket, the axe, the slasher, the spade and Humph’s rucksack filled the other two. Everything else had to be left behind. Easy.

Sal shook her head. “We need the tent. This is impossible.”

Joe liked sleeping in the tent but he hated all the hammering-in of pegs and slotting together of poles at night, and wrangling the canvas back into its bag in the morning. “We’ll be hours quicker without it. It’s summer. We’ll sleep under the stars, and we can always shelter under the tarpaulin if it rains.”

“When it rains,” said Sal.

It was Joe’s turn to worry when Beckett sliced lengths off the coil of rope to tie the baskets together in pairs. Pa and Ma always said carry the longest rope you can, but there was no alternative.

Beckett’s mother found some old sacks to protect the donkeys’ backs; they loaded Treacle with the baskets of tools and the net of hay Mr Arbuckle gave them, and Dumpling got the food baskets. The empty water barrel was tied on top, and the altimeter rolled along behind.

Beckett’s mother suggested they take the groundsheets out of Treacle’s baskets and drape them over each donkey’s load.

“You never know when it’ll start to rain,” she said, “or if you have to walk under a waterfall.”

That made a tiny bit more room. Sal stuffed in Ma’s first-aid bag, Joe added an extra bag of route-marking silks, Beckett rescued Pa’s fishing rod from the “no” pile, and Francie held out the paraffin bottle and the lantern, which was much better for drawing in the dark than a candle. Sal managed to shove them all in with the tools.

They checked their rucksacks: a sleeping bag, a change of clothes, plus another jersey and two extra pairs of underwear and socks, a warm jacket, a woolly hat, gloves and a rain cape, a mug, a bowl, a pocket knife and a spoon, some candles and matches. Joe also had his bag of orange silks, a ball of twine and the coil of rope. Francie carried her sketchbook, pencils, pens and ink.

Humph was wearing old shorts of Joe’s and his favourite red jersey. Sal, Francie and Joe were all wearing comfy old shirts of Pa’s, with the sleeves shortened. Sal had her own trousers that Ma had made her, and Joe and Francie had Pa’s old trousers taken in at the waist and cut off at the knee and held up by braces (Francie) and a belt (Joe). They all had good boots that fitted—unlike Beckett’s boots that flapped at the toe. His mother made him take them off while she waxed a thread and sewed them up. She gave him his father’s old socks, jersey and overcoat for when it got cold, which made his eyes water a bit and he had to blow his nose.

He didn’t have a rucksack of his own, so Joe emptied out Ma’s for him, and gave him her sleeping bag.

“But what about when she catches us up?” Sal whispered.

“Beckett’s a definite, Ma’s only maybe. If she does catch us up, she’ll find what she needs,” said Joe. “She’ll manage.”

When all the belongings they were leaving behind had been stowed in one of Mr Arbuckle’s empty rooms, and Beckett had his boots back on, they waved goodbye to his family and set off along the river bank, leading two heavily laden donkeys.

Humphrey could walk for hours so long as he had someone to chat to, and Beckett was a good talker so long as he had someone listening, so Humph stuck close and Beckett told him stories about the dirigible and the steam-driven charabancs he’d seen in Grand Prospect. He’d even seen a mining engine called The Worm that could burrow coal and gold out of the ground.

Francie and Joe left markers for Ma, in case she followed them. Francie arranged coloured stones in little cairns every few hundred clicks while Joe tied a strip of orange silk to a branch at eye level, so it fluttered in the sunshine.

Sal walked behind Dumpling, watching the altimeter and dodging the donkey poo. “Blooming donkeys! No need to waste your silks, Joe, the donkeys are leaving their own trail for Ma.”

But the biggest problem with the donkeys was that they kept stopping to graze.

“You sure these beasts are donkeys, Beckett?” Sal tugged at Dumpling’s halter, but Dumpling just reached for another mouthful of thistles. “Sure we’re not trying to drag two tortoises over the mountains?”

Joe pushed Treacle’s rump. “Come on, you! This isn’t a snail race.”

Treacle just flicked his tail in Joe’s face and put his nose into a wild rose bush.

It was Carrot who got them moving. She flew down and perched between Dumpling’s ears and screeched: “Sit straight, face front!”

Like magic, Dumpling started moving, and Treacle followed. And they kept going, as long as Carrot snapped at them from time to time.

To begin with there was hardly any need for route finding—the way was directly up the wide, straight valley of the Brightwater River. When they came to a fork in the river, Joe checked his compass and Francie’s sketch map and decided which branch of the river to take. The ground was level, the rise was gentle, and there was plenty of room for a railway track.

The river sparkled and they wanted to jump in. It was a baking hot afternoon but Sal kept hurrying them along the river bank where there wasn’t much shade. The shadows grew longer and longer until finally Beckett said the donkeys had to stop, even if the Santanders didn’t. At last. They pulled their boots off and threw themselves into the cool water. Beckett couldn’t swim, but he sat in the shallows and let Humph splash him.

In the middle of the night Humph cried out that he wanted Ma, and he sobbed and sobbed. Joe cuddled him and whispered, “You’ll see her soon. Just think, this is our second night on the race already. Only twenty-four days to go.”