AN UNSWALLOWABLE ROCK

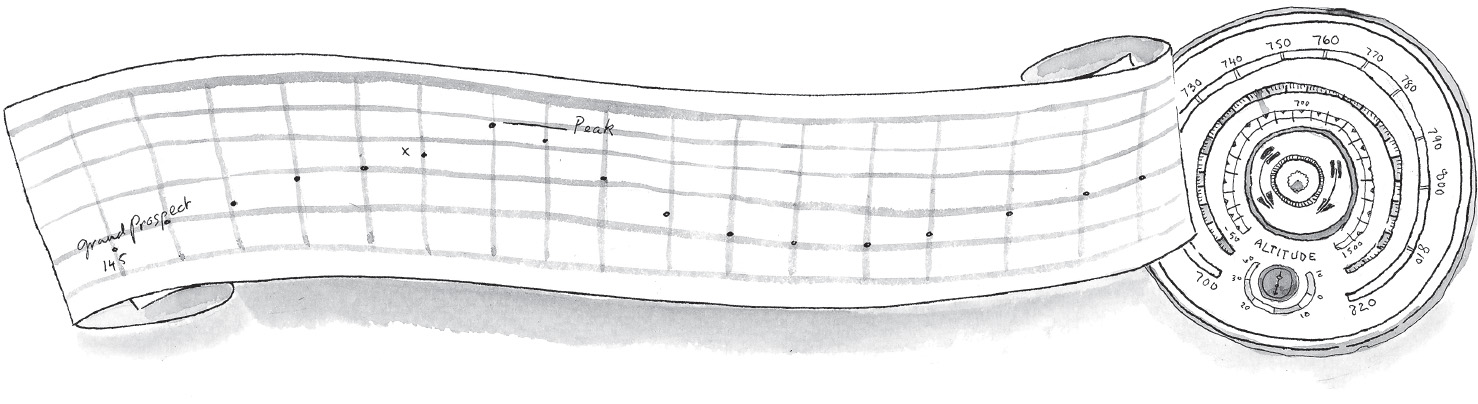

While Joe had been finding the next section of their route, Sal and Francie had worked on the map of the route they’d already travelled. Sal opened the altimeter and unrolled the scroll of paper inside. She was relieved to see that the altimeter was working perfectly. There were hundreds of dots along the scroll, one for every hundred clicks of the altimeter wheel, and they rose gradually up the width of the paper from the starting point at Grand Prospect (145 feet above sea level) to this clearing at 920 feet above sea level. Less than one foot up for every one hundred feet along—perfect for trains.

She sharpened a pencil with her pocketknife and opened her notebook. She had the whole day to do what she liked doing best, which was trigonometry. How high was each peak? How far below their track was the river? What was the gradient of the slope ahead?

Time passed. When Sal finally glanced up she was astonished to see that the sun was already hidden behind the trees. How did it get to be afternoon already? And where was Humphrey?

“Have you seen the boys?”

Francie shook her head without looking up.

“Where did they go?”

Francie shrugged.

“Francie!” Sometimes Francie was exasperating.

Francie sighed, screwed the lid on her ink pot, put down the pen with which she’d been drawing tiny trees to represent the forest, and stood up. She let her eyes go squinty and turned slowly round in a circle. Her nose was up as though she were sniffing the air. At last she nodded downhill and gave Sal a look that said nothing terrible has happened to Humphrey and Sal had to be satisfied.

She cut them both some bread and cheese and gave the list of heights she’d made to Francie, who was adding colour wash to the map she’d drawn: very thick forests were dark green, and places that were easy to walk she coloured pale pink. All the features were neatly labelled in Francie’s tiny handwriting: Black Bear Bend, Mt Beckett (2601 feet), Wait-for-Me Stream, Hop Over Stream, Crocodile Ridge and Lost Knife Gully.

“Where could they have gone?”

Francie ignored her.

Sal listened hard. Insects buzzed and hummed. A cuckoo called, and a lizard rustled away under the leaves. No voices. That morning Sal had snapped at Humph to stop asking questions and leave her in peace, but now she wished she could hear his insistent voice saying, “Sal? Hey, Sal?”

Beckett was all right. No, he was excellent at what he was good at: cooking, managing donkeys, entertaining Humph. But he wasn’t an explorer. He didn’t have a compass. Five steps into the forest and you could be lost forever.

She called and called, but there were no answering shouts.

How long should she give them before starting to search? What on earth were they doing anyway, going off without telling her? Anything could have happened. Bears. Snakes. And neither of them could swim. Cliffs. A broken leg was all they needed. Didn’t Beckett realise they mustn’t take risks—they all had to be fit and in one piece to tackle the high mountains. She was getting more and more furious inside, so when Beckett and Humphrey strolled out of the trees with the donkeys, she bellowed, “Where the hell have you been?”

Beckett looked shocked. “You knew where we were.”

“How could I know?”

“You could know,” Beckett said slowly, in his most annoying, patient voice, “because I told you. So did Humphrey. I said, ‘We’re going down to that pool we passed, to bathe the donkeys and to see if we can catch a fish.’ Humph said he’d dug some worms for bait. And you answered, ‘Right-o, good.’ ”

“Oh.” Sal could have apologised then, but instead she said, “I hope you caught something.”

“Well, no, we didn’t.”

“So what are we having for dinner?”

“You can eat boiled grass for all I care,” Beckett growled.

A few minutes later there was a terrible howl from the food store. He’d found the cheese hacked into and left unwrapped, the raisin tin lighter than it had been, and, worst of all, that someone had helped themselves to the bag of sugar and left it open. A procession of ants was carrying it away, grain by grain.

“That’s it,” he said in an icy voice, stuffing his greatcoat into his rucksack. “You all promised, but it seems the promise of a Santander isn’t worth two ears of barley. If I can’t trust you, I can’t travel with you, so I’m going home. Your mother can get her rucksack and sleeping bag back when you return the donkeys. If you return the donkeys.”

*

When Joe walked into their camp expecting to be hailed a hero, Humphrey hurled himself at him, red-eyed and sobbing.

“Beckett’s gone,” he cried. “Sal shouted and Beckett’s gone.”

“Going, going, gone,” Carrot shrieked, digging her claws into Joe’s arm.

Before Joe could even open his mouth to ask what happened, Sal screamed at him to help Francie. “Quick!”

Treacle had slipped his halter and galloped off. Joe snatched up the halter and caught up with Francie and together they chased after the donkey, skidding and sliding downhill. When at last Treacle paused, it was in the middle of a patch of stinging pinksap. He waited until Joe had the halter over his ears then he ducked away.

Finally, as the sky grew dark, Treacle allowed himself to be cornered and led back up the hill.

Joe was shaking with tiredness when he flopped down by the fire, legs and arms all scratched and itchy, for a dinner of burnt, sugar-less porridge.

“So, what happened?”

Sal told Joe what Beckett had said.

“I took a bit of cheese and some raisins,” Joe admitted.

“So did I.” Sal had calmed down and just looked sad.

“And me. A little bit. Actually, quite a lot of little bits of sugar,” said Humph.

“So did Francie. We all did,” said Joe, putting his arm around Humph.

“But we promised,” said Sal. “And we haven’t got much food. Beckett’s right, we’ve got to ration it.”

“And now we haven’t got Beckett, because he can’t trust us.” There was an rock in Joe’s throat. “We didn’t think. We should’ve thought. We have to be able to trust each other.”

“That’s what I meant before,” said Sal. “About having to think like a grown-up. I don’t know if I can. Fourteen isn’t old enough.”

Joe shivered. The dark seemed darker and scarier than before. “I wish he was here.”

“Tell him!” said Humphrey. “Shout.”

Joe climbed onto a rock and shouted “Beckett! Beckett! We’re sorry. Come back. Please!” as loudly as he could. His voice echoed down the dark valley into silence. Joe could usually see the bright side of everything, but going on without Beckett felt like a stomach-knotting, terrifying disaster.

“And we’ve still got twenty-one days to go,” said Joe.

They put more wood on the fire and huddled together, but it was a long time before anyone slept.

“Joe? Joe?” Sal was shaking his shoulder.

“What? I’m asleep.”

“We’ll have to go back. We can’t do it without him.”

Joe rolled onto his side. He was surprised at how relieved he felt. “I know. In the morning. Back to Grand Prospect and find Ma. It was a stupid idea, anyway.”