A BOOT UNDER A BUSH

Sal hoped their camp was far enough into the forest that their fire wouldn’t be seen. She left the others cracking nuts and followed the stream down to the river. She walked along the river bank looking and listening, and sniffing the air because she could smell smoke. Which team was it? And where were they?

It was nearly dark and she was about to turn back when she heard voices singing, up the hill under the trees. She crept towards them. Cody Cole and the Cowboys were sitting around their campfire singing a song about being careful not to love anyone because love only ties you down. She hid behind a tree. When the song finished they stood up and stretched.

“Four days to go, men,” said Cody Cole. The flames lit their faces from below, making them look ferocious and ghoulish.

“No stopping the Cowboys,” said one.

“Whatever it takes,” said another.

“Victory at any cost, boys. All together now,” said Cody. They put their right hands into a stack. “Victory at any cost.”

“Cowboy victory!” they called together and raised their fists into the air.

Sal shivered. When the men had all settled down on their bedrolls she stole away but was startled to hear more voices whispering in front of her. She stopped, but something was breathing right beside her. Then a quiet whinny. She had nearly bumped into a Cowboy’s horse.

A twig cracked. A horse? No. The whispering people were now just behind her. The only safe place was up, so she felt for a branch and pulled herself into a tree. She pressed herself against the trunk and breathed again. She’d had a lot of experience of hiding in trees when Pa or Ma called her and she wanted to be left alone to read or think; for some reason, when adults are looking for someone they almost never look upwards.

The whispering men came right underneath her. There were three of them; one had a shuttered lantern. They reeked of tobacco. Monty’s Mountaineers. Her first thought was that they were planning to hurt the horses. But no. They fussed around untying the horses’ tethers and hissing at each other. Then they led the horses quietly away.

Sal waited a few minutes and slid down. It was completely dark and she hadn’t a clue how to get back to the others. Out of the trees and towards the river—but which way was that?

As soon as she’d stumbled a safe distance from the Cowboys’ camp, Sal paused and ran her fingers over some tree trunks. The side the moss was growing on was north—towards the sea. Soon the slope helped too; the right way was down. After that she heard the river. Then she was out from under the trees and there was a little light from the stars and the moon to help her find her way back along the river bank.

She was just wondering how on earth she’d know which of the many little streams she was crossing was the one that led up to their campsite in the forest when she heard a whistle, and Joe popped up from behind a bush.

“Beckett went up and down the river looking for you. And Humph cried,” he said.

Sal was very sorry that the others had been worried. “Thanks for waiting for me.” She held onto the hem of his jersey and let him lead her under the dark trees to the glow of their fire. “Is there any dinner left?”

Humph was asleep, but Beckett put another log on the fire and Francie’s anxious face shone out of the darkness. Sal thought Beckett was going to snap at her but he just looked relieved and passed her a bowl of cold rice with nuts and wild sorrel chopped into it, which she wolfed down. And in between mouthfuls she told them what she’d seen and heard, and they listened with growing excitement.

Joe nudged Beckett. “We can still be first! We might not have the best maps if they mind about pencil but we can win!”

“Maybe.” Beckett nodded slowly. “If the Cowboys waste time fighting with Monty’s men, we might be able to overtake both of them. Tortoise and hare. I wonder where the Solemns and the Women Explorers are?”

“Four days to go,” said Sal.

They hadn’t gone far the next morning when they heard a gunshot. They looked at each other and dragged the donkeys further under the trees.

“They could have been shooting a pigeon for dinner. Or a rabbit,” suggested Joe. He hoped they were.

“I don’t care if they shoot each other, just so long as no one sees us and decides to sabotage us again,” said Beckett. “We’ve got to be the invisible tortoises.”

“What is a tortoise?” asked Humphrey.

“Shh—” said Sal.

A horse and rider pounded along the riverbank, quickly followed by another. The second rider slowed, raised a revolver, fired at the first man then galloped after him.

Joe ran to see. “He got away!”

“That was a Cowboy with the revolver,” said Beckett, “so they’ve got at least one horse back.”

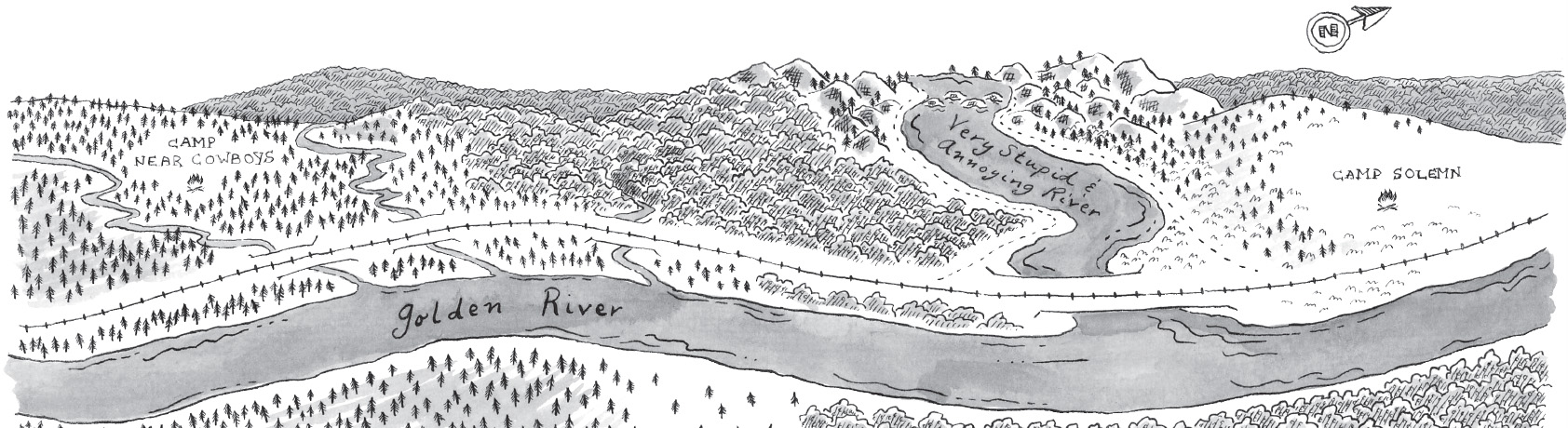

They came to a river that flowed into the Golden River—a tributary too wide and fast-flowing to cross, so they had to follow it upstream. It was frustrating to be going in the wrong direction and uphill again. Joe kept scrambling down the bank to see if he could see a crossing place but the river was running through a gorge.

Sal took bearings from a hill on the other side. “The railway can go straight over here but we might have to go hours round. So annoying.”

Humph threw a stone down the hill. “I’m going to call it ‘Very Stupid and Annoying River’.”

“Let’s hope it turns out to be too short to write its whole name on the map,” said Joe.

“It is,” said a voice. “Only a few minutes further to a crossing place.”

It was Agatha Amersham. And there were the other members of the Association of Women Explorers. Their camp was colourful, with a row of stripy stockings hanging like flags from a line strung between their two small tents. One woman was sitting on a blanket with a bandaged foot stretched out in front of her. Another was brushing their horse, whose leg was also bandaged, and the fourth one was tending the fire under a steaming billy. She looked up at the new arrivals.

“Good heavens, it’s the children!” She left the fire and crossed the grass to peer short-sightedly at them through her glasses. “Well done, well done. Sit down, rest your legs. My goodness, I think this might be a hot chocolate moment, don’t you, Agatha?”

“Excellent suggestion,” said Agatha. “Mugs out, everyone.”

There really was hot chocolate. The short-sighted woman, called Daphne, broke a wedge of chocolate into each cup and topped it with hot water and white powder, which she explained was dried milk.

Joe had never drunk hot chocolate before. It was glorious. He tried to sip it slowly to make it last.

“This is my best ever, ever, ever,” said Humph, grinning under a chocolate moustache.

Beckett asked what had happened to their horse and whether it was badly injured.

Agatha frowned. “Someone, we know not who, hurt our beloved Boudica.”

“Two nights ago, someone came into our camp, sliced through her halter and stole Boudica,” said Daphne. “We searched and searched and eventually Harriet here found her halfway down that bank with an injured leg. We managed to haul her up but in the process Harriet fell and sprained her ankle badly.”

“Idiotic thing to do,” said Harriet.

“Heroic,” said Agatha. “If you hadn’t risked your life we’d never have got Boudica out alive, would we, Zinnia?”

“Boudica will recover,” said Zinnia, “but it will be a couple of weeks before she can walk far. Nothing to be done but make a comfortable camp and wait.”

“That’s terrible,” said Sal, and told the women about the war between the Cowboys and Sir Monty’s team.

“So it’s Monty’s team who are the horse thieves.” Agatha snorted. “I despise people who would allow a defenceless animal to be hurt in order to gain an advantage.”

Carrot, who’d been pecking about in the firewood pile, flew onto Agatha’s hat and dropped a large green caterpillar onto the brim. Joe tried not to laugh.

Francie rummaged in the first-aid bag and found Ma’s pot of salve.

“It’s magic,” said Humph.

“It really is.” Joe held out his hands. “Just a few days ago I fell down a cliff and my hands were pulped. Now look.”

He wiggled his fingers to prove they still worked, as they were far too dirty to see any scabs and bruises.

Zinnia took the salve and her eyes welled with tears. “Can you really spare it?”

“Of course we can,” said Sal. “It works on humans and horses both. You’ll probably be able to walk again tomorrow or the day after, Harriet.”

The women said how grateful they were.

Beckett cleared his throat and turned to Agatha. “Excuse me for asking, ma’am, but would you, by any chance, be able to spare us a little ink?”

*

“They were so kind,” said Sal as they splashed over the river at the crossing place that Agatha Amersham had shown them. “And they stuck together.”

“They could have abandoned Harriet and Boudica and raced on,” said Joe. “Cody Cole would have. And Monty.”

“I’m going to have hot chocolate every day when I’m rich,” said Humph dreamily.

“And we have ink!” said Sal. “That was very clever of you, Beckett.”

Beckett’s ears turned pink. “Well, there’s no harm in asking, is there?”

When they reached the point on the opposite side of the gorge that she’d marked as the place for a bridge across Very Stupid and Annoying River, Sal stopped to measure and Francie inked in the map. Joe and Beckett persuaded Humph to stay with the mapmakers and they went on ahead. Beckett took the bucket, determined to find something to cook for dinner, and Joe took the slasher to clear a path through the undergrowth, which was much thicker on this side of the valley. Except he didn’t need to, because they soon came across a ready-made path that was going in exactly the right direction. Beckett thought it must have been trampled by animals—bears perhaps, or wild pigs—though they couldn’t see any spoor or scraps of fur on the bark of trees. Joe held the slasher tightly, just in case they met something fierce. Beckett had his catapult and knife at the ready in the hope that the path had been made by a wild boar; he talked of roast pork and described how to make delicious crackling.

Joe noticed a flash of blue. A branch had been pulled back and tied to the one next to it with a blue thread. He untied it and showed it to Beckett.

“Strange. Have you ever seen the like?” asked Beckett.

“Never. It’s so strong.”

Beckett tried to snap it but he couldn’t, even though it was as fine as a hair. “You could wind up a mile of that and still hold the ball in one hand.”

A prickle bush had been chopped off at knee height; some person had definitely cut this trail, and that someone was ahead of them. They came to another deliberately tied-up branch, and another.

“It’s got to be the Solemn men,” Joe said. “That thread is totally scientific. And it must mean that at least some of the Solemn men are behind us. Brilliant!” said Joe.

“Except maybe the following Solemns have already passed here and just not bothered to untie the threads,” said Beckett.

“Oh. That’s true,” said Joe sadly. “I think my brain’s slowing down because I’m so hungry.” The delicious full-up feeling from the hot chocolate had long since worn off.

But at least the track was easy to follow and soon they were walking along the bank of the Golden River again. Late in the afternoon the trees thinned out and they came into a clearing. The sun was bright, but there was a cold wind scouring the valley. Joe shivered and crouched by the water’s edge for a drink. He didn’t immediately notice the booted foot that stuck out next to some crackerjack vine.

When he did, he nearly fell backwards into the river. He stood up quietly. There was another boot, and both boots were attached to legs, brown-knitted legs, and above that a brown-knitted jersey. And a head. It was one of the Solemn men. Asleep? Or dead?

Joe coughed loudly but the man didn’t stir.

He called, “Hello? Hello?” and looked around. Definitely no one else there. He held his breath and crept nearer. He’d never seen a dead person before. He touched the man’s hand. It was cold as snow.

Then the man groaned and Joe’s heart started thumping again.

“So you’re not dead, then? That’s good.” He squatted down. The man looked like the leader, Keith Skinner, though it was hard to tell as a lot of his face was covered in a new beard and moustache. His face was blue-tinged in the places that weren’t deeply tanned, like his eyelids, behind his ears and below the hair on his neck. His eyes opened—even the whites were blue.

Carrot landed on one of the man’s boots. “Dearie me.”

“Are you hurt? Where’s the rest of your team?”

“Nearly there,” Skinner mumbled through clenched teeth. “Steak for protein, iron, more hydrogen …”

Joe touched him on the arm. The man’s clothes were sopping wet. “Did you fall in the river? I think you’ve got hypothermia.”

There was a slasher lying near Keith Skinner’s rucksack. Inside the rucksack was a ball of the blue thread, a scarf, which Joe wrapped round Skinner’s head and ears, some chemical-looking jars and packages, a cup and a plate. No food, and no dry clothes.

Joe took off his own jacket and tucked it over Skinner. “Lucky for you the cavalry’s coming.”

“What have you found?” Beckett came down the river bank, bucket in one hand and a dead pigeon in the other. “It’s a Solemn! Is he by himself?”

“Seems to be.”

“He can’t be lost, surely?”

“Don’t know. He’s freezing.”

They quickly dragged dry wood into a pile and made a fire. When Keith Skinner’s lips were less blue, he whispered, “Food.”

“Can we spare anything?”

Beckett lowered the bucket. There were eight small eggs in it. “Pigeon’s eggs. He can have one, I suppose.”

Keith Skinner’s eyes were huge in his bony face. He grabbed an egg, broke it into his mouth and swallowed it raw.