Not so many years ago …

Are you sure about that? Didn’t that lightning strike nearly twenty-five years back? Isn’t time one of the most difficult stories to tell straight? Can you really remember when you were standing near that tree outside Parma, ten years before you would move to that very city with your second husband?

Yes, I can. I can see how the branches were sheared off and the tree whacked in two near the bottom. I remember the smell of smoke and how fast the lightning came and went. I remember the thunder all around and how my mind joined it to the crack of the tree splitting. I remember the smell but I can’t describe it or the dead percussion of the earth as the tree hit the ground. More than anything I remember how close the force came, how I was a few feet away, and how in that moment I stood outside the circle of fire.

And now? Why are you searching those details?

I suppose I like the vulnerability, the coincidence, the cosmic power, the truth: it happened. I’m quite a private person. From the time I was asked to write a book about Parma, I began to realize that by telling stories about a real place, I was going to change my life. A silence would open. The lightning was not going to miss me.

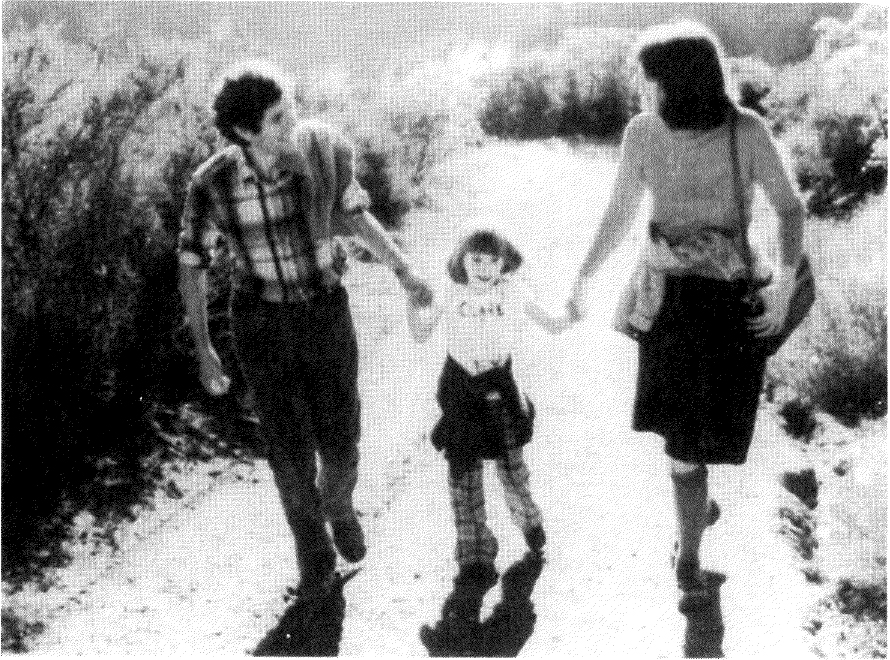

I moved to Parma, Italy, from Palo Alto, California, in October 1981, ten months after my marriage to Paolo Menozzi. My husband, an Italian population biologist, was offered a chance at the most coveted of prizes, a university chair in his hometown. I, an American, a writer, with my six-year-old daughter, Clare, adopted by Paolo, left Stanford University in order to follow him.

Those two words, follow him, burn on the page and soon kindle into flame. The words are a past, fastened in Parma, one place, happened and happening, day in and day out. The words link me to all the Ruths that ever were. They press down hard on the writer and freedom seeker whose search oscillates between open rebellion and inner contemplation. Haven’t I always known that there is no one and nothing to follow except my soul’s quick motions?

The wife in me (and this was Ruth’s story) questions but does not halt in front of the words. The mother in me trembles at the responsibility of having altered a child’s roots by changing countries, but each part, since a life rarely finds instant and obvious unity, subscribes to the move: the following because of him. Following him was a felt, necessary decision. To become a family we needed to stay together. From the beginning, within the choice grew an ideal of equality, a nearly untranslatable concept given the extent of our different assumptions about its meaning. It is true that if we had moved to another Italian city, if we had defined ourselves outside of Paolo’s family and customs, this whole book would be different. That fact, as strong as it is, can be said about the effects of any major action.

Italy has drawn centuries of pilgrims and pillagers through its unbearable and unconquerable beauty. Samuel Johnson observed—his statement corrected to include the female half of humanity—“A person who has not been in Italy is always conscious of an inferiority, from not having seen what it is expected a person should see.” I loved Italy from earlier experience of living in Europe, writing, teaching, and doing archaeology. I was anxious to absorb its artistic stimulation as someone who belonged. Waking every morning as a permanent resident of an ancient land suggested much to me as a writer, but the idea of fitting was wrong.

Not getting a job in the university—open competition is not a usual practice—was painfully difficult. It took disciplined acceptance to see that the near-vacuum I chose offered me, in time, a gain. Saying no to the medieval patronage system created free, if rocky, ground around my life. This specific quality of going no further, of drawing lines that then make fitting in an obstacle, is a darker or lighter gift often bestowed on poets. It leaves irreversible, at first cranky and then guiding, grooves in the wheel of self.

In spite of my conscious choice, I complained and thrashed. I had no regular job: no independence, no formal contact with others, no salary. In Parma, my life as a writer washed out into an undefined isolation. I hated what I professed to want: solitude offering me time to explore my own heaven and hell. I wrote in the house. Its oppressive cowl covered up my life. I had few friends. Literature was a far-off country to my daily life. It was as if my whole struggle for independence as a woman had folded back upon itself. Writing prose placed me against the other and otherness—Italian society, its nuts and bolts—in a concrete, factual way. Italy was my country—not just its beauty but its uglinesses—and I couldn’t identify with it as mine—perhaps because in Parma the pressure to conform excluded so much difference. Poetry, with its focus on mind and voice, witnessing and memory, rhythm and sound, contained infinitely greater possibilities for survival and lyrical discovery, especially since I had to stay put. I would write with my life. Italy, beginning with its physical marvels, would work its way in.

I followed him. It was Paolo who so often reminded me that poetry gestates in loneliness and deepening, not just space and stimulation. Had I forgotten that most poets die undiscovered? Paolo was quite surprised by my restless American impatience, my optimistic hoping to arrive, my belief that art makes flying leaps. How had I come to imagine the life of poetry as being in touch? I balked at fixed, repressive definitions thrown out by provincial Italian lives around me. I didn’t want fame, but I would not give up touch—touch with substantial experiences, with others who were creative and searching, touch inside words so that they launched back, newly defined, into art.

After three years of sending out work, finally a sign came. The letter with a blue prioritaire sticker arrived from Switzerland.

James Gill, a publisher and writer, who lived in the worlds and bookshelves of Russian, French, and English, became an inestimable friend. Unpaid, I joined his magazine. A nearly seamless border opened between us. Often a few words over “the gray receiver” would lift my day into sharing life in its fullest sense. We met often and, to great advantage, in extraterritorial places. Connections grew deep along a vast American prairie (or was it a snow-glittering Russian steppe?) of poetry, music, philosophy, and feelings. Generous, vulnerable, brilliant James had another aspect: he lived with a fatal disease. Though he had mastered many branches of knowledge, his most impressive study involved steadying himself like a large, newly winged bird over a stony cliff.

But before and after James’s first letter, writing in Parma went on as slow fighting for air. For Paolo resistance was the nature of life. One didn’t ask or expect, except within the family. Struggle was how Paolo had grown up. He resumed that history by returning home. His grandmother’s favorite saying was “La vita è affanno.” “Life is troubling.” The translation implies searching. Rosalia, who was the eldest of seventeen children, might have preferred “trouble.”

Parma, where Paolo had a job and his family, was a place for me to sit still and write. I was upset and often lived in my head. How could I ever find my subject? Sharp, defining instants—slow-motion openings of grace—kept me from sinking. Often they were seemingly as casual as a butterfly landing on my shoulder. Then, in a moment, the world fluttered into another level of order. Although they were difficult to believe, these intense meaningful feelings were more difficult not to believe. Their depths helped me to grapple with my own poverty and suggested experience I could never exhaust.

Equally challenging and painfully uncharted was the adjustment required as a mother, trying to live a family life in another culture. Clare, because she was six, had no choice about following. She was carried. We moved. The phrases break up, except that the choice was wanted. I will never know how much of her basic sense of identity was diverted. Nor perhaps will she. Her American father has evaded the responsibilities and joys of her life. My family, often absent, began to spread out thirty years ago, after my father’s sudden death. She has put down European roots. She has an Italian family. She’s shy about America.

In considering Clare’s life, we knew that Parma was a quiet, culturally rich city for a child. Paolo’s family would reach out. Six-year-old marvelous Clare would unbuckle her squat California sneakers and exchange them for little Italian leather shoes and socks. She would learn to be a Carthaginian who battled the Roman army. I would read her books about George Washington and Mrs. Tiggy-winkle and track the redoubtable creatures from Oz. Fortuna, Clare’s Palo Alto cat, would live in the house. Step by step, we would all learn to sit still in Parma.

The pressure on those optimistic words pushes inside almost like the 35,000 feet of atmosphere that in a few minutes stands between an airplane and the ground. Don’t thinly about it. How can you understand the cold on the other side of the plastic window? How can you explain the wonder of seeing vast dissolving white clouds nearly rub on your palms? What does it feel like to look straight down above the onyx, mountainous surface of the ocean? If you fell now, it would be very cruel. Going on, you will land.

To become a family we needed to stay together

The flight is not an odyssey. I’m not on a journey to Ithaca. I am moving east toward our home. A pilot is taking me to Milan, back from my yearly visit to the States. Clare didn’t want to return this time. Paolo hasn’t come for years. He’s in Brussels. I wriggle in my seat and drowse, cramping my long legs and arms for a sleepless night as my language idles and then disappears, like the seven hours that are wiped from my watch in one swift twiddle.

In the night sky, while the flickering lights of Chicago, Cleveland, Pittsburgh sweep up and fade out, my language thins and leaves the ground and becomes unbearably, and at the same time interestingly, private, internal, not spoken. Morning: a nubby fog that will burn off wraps the ground. Italian customs men with their yellow trimmings arrive. I start speaking a language I can speak and like to speak, although Clare tells me—perhaps hyperbolically or perhaps because hers is that of a native speaker—that my Italian is half invented. (Paolo rarely corrects my twirling sentences.) Voices in the airport begin to sound frantic and men’s voices seemingly grow an eighth of an octave deeper. I am living in Parma, two hours further south. The journey isn’t over.

Parma is a provincial city of fewer than 200,000 people, in a region which produced miraculous music, art, and writing that affected the entire world in the last two centuries. Among the strong talents: Giuseppe Verdi, Arturo Toscanini, Renata Tebaldi, soprano, Giovanni Guareschi, who wrote the Don Camillo stories, Attilio Bertolucci, poet, and recently his son, the filmmaker Bernardo. Each left his or her native ground. Some were persecuted for political reasons; most sought cities with greater opportunities. But many in old age returned to settle in the foothills or on the flat farmlands banking the city. Or they rejoined their birth villages along the twists and turns of the Po River.

The younger Bertolucci, while making a film in Tibet a few years ago, stood where two strong rivers converged. He asked their names and was told they were called the Mo and the Po. “I knew then that I had to go home, back to Parma. When I admitted to myself that I couldn’t even remember the word in dialect for plowed-up clods, I knew that I had lost a sense of who I was.” As rhetorical as this sounds, it contains truth.

In Milan, at its eastern airport, I am less than two hours from our home in Parma, the city of sweet, enveloping fogs and flat horizons marked by majestic poplars. Yet I immediately feel its dark superficiality. My elegant city is unforgiving, petty, busy, rich, and yet tolerant to the point of indulgence. It is a complicated city of masks and narcissistic poses, of caustic undermining irony, sophistication, epicurean appetites, and earthy realism. Its court-like beauty suggests nearly nothing of the pragmatic democracy that I know in my bones. The layered city has a relationship to time that stresses its diurnal rhythms and denies time’s rich uniqueness. As in most provinces, the work of censorship exists: one person on another. Conformity is a long black rope of indeterminate strength tying most people down. Parma’s heroes and heroines are strong, abrasive characters and often physically brave.

Everyone says that Parma is an easy city to live in. Its physical charm is great. In vivibilità, a measure of livability that includes mean income, safety, culture, space, cuisine, Parma was recently voted the second most desirable city in Italy, after Bolzano. Yet as a merchant said to me: “Emptiness is our problem. We want nothing anymore. We go to church, but we go in at eleven, since we eat at one.”

The city’s center, a mix of medieval, Baroque, eighteenth- and nineteenth-century French-influenced palazzi and churches, nearly feels (except for the early medieval stone) like formal gardens. The streets curve in appealing human ways, and buildings follow the curves. The edifices are mainly painted in earthen colors and most are freshly plastered. The stronger golds reflect, not consciously, the deep amazing yellow of the region’s richly textured cheese, parmigiano, and the pale reds are the color of its famous, delicate ham. Some buildings venture into taupes, persimmons, willow greens. All in all, the city is gorgeous.

If one looks up, not far above the medieval cathedral doors, a nine-hundred-year-old figure at the center of the arch smiles down. It is a benevolent sun, and next to it splay fat carved bunches of grapes on vines. A kerchiefed peasant with a basket is gathering them on her hands and knees. In the arch, chiseled in marble, are images of planting, threshing, slaughtering a pig, curing its plump oblong shape by hanging it upside down to weather. The blessings from the rich alluvial Po plain influenced and inspired worship and are announced as the basis of life in the powerful stone façade. Yet the land, usually parceled out among nobles and landlords, produced centuries of bosses, starvation, bloody feuds, humiliation, and limits for the tenant farmers. Bertolucci made an epic, 1900, about the harshness of life in this region from a Communist point of view. He described as inevitable the peasants’ demands for social justice finally obtained by using violence. Ermanno Olmi told a similar story about Lombardy. In his film The Tree of the Wooden Clogs, which uses the lens of a Catholic faith, the sense of history turns to the individual’s learning acceptance. The five-story pink octagonal baptistery, begun in the late twelfth century at right angles to the cathedral and the Bishops’ Palace, seems a noble’s cake offered for consumption by the eyes of the people. Inside, the frescoes tell an encyclopedic version of the Bible. Today, too, the baptistery’s fantastic shape and magical pink color make tourists smile in amazement.

My language, English, ends definitively at the airport. It stops as a given force that opens doors and creates exchange. Its space and assumptions disappear. I use the word “space” deliberately rather than “ground.” Space pertains to my history. It is an image of growing up in America’s physical enormity and its transcendental myths. I feel the reality of losing this space as if I am going underwater. Like Philomela, my tongue is cut out. My mother tongue, absolutely truncated, suddenly nearly replicates a dramatic experience of women’s traditional ground, a passive, acute sense of observation and inner, unspoken flow. All that is assumed by language, starting with culture, turns into another history. I, who trust words, often discover that language is a foreign land where I am trying to define and keep alive another existence. This strong, confusing sensation sometimes strikes when I am speaking aloud in Parma. I reach out and find myself being soundly remonstrated for what I have just said. People can be very practical here and existence is demonstrably concrete.

My ears and heart don’t drown at the airport, but they reconnoiter, introspect, withdraw inside. Parma has emphasized an awareness in me of distance, of differences between any two people. I followed him. The commitment to stay here caused such major alterations that I’m not sure a pledge of such a deep nature should be made to any source but God.

Misha is Clare’s cat. The way he has developed, as well as what happened to our other two pets, is emblematic of our lives’ lighter collisions. Without touching anything essential, they show how frail and flighty, how hard to pin down, normality is. The pets, like mischief, create a set of frictions where there are no victors. They may be a part of multicultured existences.

The lawyer who lives behind us noticed Misha some months back. He wanted him because of his eleganza. The lawyer’s cat, Dick (pronounced Deek), receives regular scrubs in the tub and has his white fur gathered by little rubber bands to make ringlets. The lawyer prods him continuously, the way children are badgered to behave here. He is an animal, and therefore needs to be domato, trained, stood to attention. He must reflect well on his padrone. As I was taught to expect as a child growing up in Wisconsin, having been raised in such a heavy-handed way, the lawyer’s cat scratches, bites, and is without pity. So Misha’s blissful character was extolled. We were objects of envy. And his coat of fur … “Bello, bello, bello. Davvero. I mean it,” the lawyer said.

The next acts were simple Machiavellian corruption on the lawyer’s part. The minute, prune-faced man enticed Misha with meat, tinned fancier food than the dry health stuff we offered. The lawyer wanted what was ours. With this crude but effective tool he successfully lured him into their far less intellectually stimulating household. Misha began to live there on and off. After inspecting what was featured at our house, the cat would make a flying, awkward leap out a rear window, back to the world of Parma grassa. This phrase literally means fat Parma, the Parma of excess, decadent, indulgent Parma, of rumored orgies, highly paid mistresses, gambling away family fortunes, and its tamer version, rich banquets that end after eight or nine courses in a humid dawn. The lawyer, as do most Parma households, offered lovely food.

Reasoning that we must interrupt the miseducative cycle, we chose the fairly bland and not too hopeful course of polite exchange. We cornered the lawyer at the newsstand one morning and explained how the cat was Clare’s, how the lawyer must desist from feeding Misha and keeping him hostage in his house. The hopeless logic of asking for normal limits reminded me of Licio Gelli’s internment in Parma not that long ago. Gelli is a businessman indicted in the fall of the Banco Ambrosiano (a collapse that in the late 1970s and early 1980s brought on murders and suicides, as well as rumors leading to the highest socialist and Vatican circles). He was detained for trial by being kept in a specially refurbished prison cell outside the jail in Parma. The facts were well known. Gelli’s “cell” had a new tile bathroom, decorator couches, and a spanking modern kitchen. After fifty days, health reasons sent him home. Indulgence is a kind of slipperiness that soon becomes a slimy slope that honest citizens accept with nearly good-hearted resignation. Power moves are assumed to be corrupt and corrupting. If one is caught and is powerful enough, it is assumed, too, that punishment will not be commensurate with the crime. Pleasure, in these ambiguous situations, is hardly a source of shame or contrition: it’s always happened.

In the end, to get Misha back, we switched foods and entered into a competition to seduce Clare’s cat into staying home. We succeeded in creating an obese gourmet.

“You must stop feeding our cat,” we said, aggressively raising our voices over the back fence. “He’s more than eighteen pounds.”

“I don’t mind,” the lawyer said. “I don’t mind at all. We give him good food, happily. Misha’s so cute and my granddaughter loves him. She likes to take him into the bathroom and sit him in the bidet when she washes for school.” (Ugh, we thought to ourselves.) “Of course,” we said, “but you understand, Mr. Lawyer, he’s Clare’s cat. You mustn’t encourage him with food.” Then we lowered our brows into belligerent scowls. “You understand, don’t you?”

Nothing changed. Misha began looking like a Botero statue. One rainy overcast night, we received a telephone call about ten o’clock. Unashamed, in a complicated admission of how things lay, exposing his untenable position, the lawyer confessed. “You know how cats are, they don’t like to go out in rain, so don’t worry. He’s in front of the TV and in his box. He’ll just stay with us. I would hate it if we were responsible for his catching cold.”

With that testimony, the lawyer flummoxed me. “You know,” I said, “that the cat mustn’t be encouraged to stay. Will you be fair? Have you ever heard of King Solomon, or Lovelace, ‘I could not love thee, Dear, so much, lov’d I not honor more’? You’ve got to be joking, Mr. Lawyer. You’re killing him, you’re wrecking his nature, confusing him, and breaking Clare’s heart. He’s not yours.”

“For heaven’s sake, signora, it doesn’t hurt. He’s Clare’s cat. I know that. But I’m old. There’s not that much pleasure to life. If you could only see how much my granddaughter loves him.”

Paolo came down halfway on the lawyer’s side. “At least you know where Misha is. Otherwise he’d be on the street and probably killed on the busy Viale Duca Alessandro. The drivers are crazy,” he said, reversing himself, using the finely sharpened tools of compromise that replicate the jungle in petty bourgeois HO-gauge versions. “And it’s for a kid he’s doing all this.” “And ours?” I ask, upset by the omnipresent logic of the bella figura.

When Clare comes back some nights, if Misha is not home, she telephones the lawyer. There is no scene over the wires. There is utter civility and no guilt or nastiness, as if no rule had been broken. Everything has been wrenched into a place where words have little meaning, and if used aggressively, the fight will only be stubbornly refought—uselessly, because we have no power to control Misha’s movements.

“Of course I’ll send him home,” Mr. Lawyer says pleasantly. “He’s here at my feet, just resting in his box.”

Clare, passionate in her feelings when she can get them out, after putting down the receiver and waiting for the cat to reappear, often shouts, “I hate the lawyer.”

Some evenings after dinner, I go into the backyard, looking for justice or revenge. I try to inspire the lawyer to release the cat by lifting my voice in a high-pitched approximation of an unabashed Appalachian pig call. “Here, Mee-shee, Mee-shee, Mee-shee,” I boomerang around the apartment walls. I enjoy the shattering seconds of exposure. Often all the lights go out in the lawyer’s house, as if the chilling sound has reached their hearts. The shutters instantly drop in a whir of clicks. I persist with the high, embarrassing call. This public pressure produces some effects. In the dark, usually, from a crack in the ever so slightly lifted shutter over the stairs, a fat shadow squeezes through.

Recently Misha has taken up sex. He leaves our house after trying to spruce up the corners of the living room with his new scent. He returns home with bloody nicks, crusted with mud, giving off the strong reek of his animal life. This morning he came in the front door wafting of lemons. His fur had no oil. It fluffed. “That goddamn lawyer,” Clare shouted. “Shampooing him. It’s not fair. I hate the lawyer.”

Our dog, Lulu, was acquired because of a series of misunderstandings and misread signals—not really intercultural misreadings. Lulu (pronounced LooĹoo) was a misplaced translation of what was needed for Clare. Clare wanted a dog, a noble dog, and we, finding a frantic, abandoned one in need of rescue, forced Lulu upon her, as a lesson. Lulu never discovered a streak of heroism in herself. The poor animal is as far from nobility as a carp is from a blue heron. Insecure, self-protecting, she, like most dogs, sought out the woman in the house for affection. She became mine.

Lulu, too, leads a grassa life, marked by food, power struggles, and messy borders. She has a round of eternal feeders and no clear sense of loyalty. The worst enabler from our vantage point is Signora Biocchi, who splats down whole chicken parts from her second-story window. Lulu stands pointing in her direction each morning, after Paolo leaves. She demolishes the evidence quickly, knowing that she has broken the rules. She shamelessly fawns. Signora Biocchi lets us know at high volume that the dog loves her more than anyone else. “They,” she mutters to her grandchild, Antonio, “are calling the dog back because they are jealous that she loves me more.” This monstrous observation is usually put forward in an operatic sotto voce. Words are inflated, idle, and unbearably empty.

Sometimes I run into Signora Biocchi at the corner. She has taken Lulu to the park and is sneaking back. She, Antonio, and the dog have been romping in the grass. About a year ago, little Antonio, upon seeing me, used to squeal how much fun Lulu was. Now his grandmother has taught him to dissemble. Signora Biocchi and Antonio usually fall into intense conversation. Lulu keeps jumping up on them. Their proximity to a triangle is unconvincingly orchestrated as sheer coincidence.

Signora Biocchi has instigated the outing to the park because she is babysitting Antonio for the afternoon. Most likely her wish to appear more grand in his eyes and to offer him some special fun made it impossible for her to keep to the straight and narrow. If you explode, she will deny to your face that Lulu has ever spent a minute with her. An opera is being born. Unrepentant, she will wildly rattle the saber. In front of the child, who sees his grandmother heroically resisting the enemy with a lie, she might shout as she clutches him, “Your rules keep my little grandson from a dog whom he loves with all his heart.” “Bad signora,” Antonio says, shaking his mustard-colored, curly head at me, half menacing, half sad that our fat, friendly dog isn’t his.

The final decision about Lulu was based on a hexagram I received after casting coins for the I Ching. The fatal line of emphasis said, “There is room in the world for everything.” Clare, much more than Paolo, questions how I ever interpreted that line as meaning that the dog should be hers. “Don’t you think it could have meant that the dog would have been fine, left abandoned?”

Lulu in some way has fulfilled both Clare’s idea and mine of what the I Ching meant. Lulu uncovered propitious niches: people’s loneliness. She is a dog for all seasons. Sly and sensitive, she is called by many a cristiano. She becomes the object of a daily ritual in which a grandchildless man provides her with a cookie on a napkin. His offering is as neat as the tight wiping of the chalice in the mass by our local priest. Lulu so enthralled a woman on the block beyond ours that she prepares a steaming bowl of rice and vegetables for her each morning. We discovered this when the alarmed woman arrived at our gate in a faded yellow bathrobe and dirty padded slippers. “Has anything happened to Lulu? She usually eats at our house before nine. Is she sick?”

Then, almost as if these pets reflect culture, we come to Fortuna (pronounced For-too-na, instead of For-tew-na, because she is American). She was acquired, for the cost of an inoculation, from a pet shop on University Avenue in Palo Alto, now nearly nineteen years ago. She was alone, the last kitten, defined by undistinguished black and white archipelagoes of fur. She appeared wet and miserable as the sun beat down on the shopwindow. Black and white, she was like her name, Luck: dark and light, yin and yang, good and bad.

She belongs to Clare and Paolo, and took her first eighteen-hour flight heroically, inoculated, accompanied by voluminous documentation. Italian customs officers never looked at her papers or into her box, where she sat, miserable and slick, in what was a sea of airsickness. She has lived here, gotten used to another garden, different trees, other cats, and for many years spent weeks in the summer, when the weather got ferociously hot and sticky, vacationing in the mountains in which Dante situated Purgatory, sleeping in the cool of Paolo’s mother’s house and its surrounding fields.

The only time I took Fortuna to an Italian vet she proved her fierce sense of self and territory. Never one to spare the mere edge of a claw to express her need for space, she made the transition to Parma holding fast to a dignified perception of borders. She never bows or appeases. She has never been a feline actress.

The visit was undoubtedly a shock for her, but it was one for me as well. Upon meeting Fortuna for the consultation, the vet, a professor at the veterinary school, of all inconceivable things, grabbed her by her nearly hairless, then thirteen-year-old tail and yanked her into empty space, while his obsequious students, encircling the metal examining table, took notes. Fortuna gyrated and wildly clawed at him. “Signora,” the obese and puffing man shouted as he forced her squat on the table, “you have a terrible cat.”

“How would you feel?” I asked, with undisguised disbelief and disgust, quietly of course. He ignored me and went on with his recitation. The professor released our small feline from his heavy grip, and as she stirred, he unconscionably brought down his other thick, fat hand hard on her back, bare of all its fur—the original cause of the visit. Here was a dark soul used to kicking and prodding animals, to seeing them slaughtered. He hit her rippling spine as hard as a farmer knocking out a rabbit before skinning it. Fortuna screamed. She whipped around to bite him, but with none of the sadism in her response that was in his wicked blow. Fortuna’s black-and-white body flew off the table. Clumsy, he lifted his hand too late. She fled across the room and hunched down under a lab bench in the room’s far corner. The students continued taking notes. The vet, meanwhile, shouted theatrically at me.

“Signora, your cat is a beast. I can’t handle her,” he said, waving his mildly injured hand like a prima donna. “Put her back in the cage. She deserves her fate. She’s been worked over by a lot of bad males.”

“Like you?” I asked, surprised by my words and hoping that the passive students would puzzle the question into their notes. I still can conjure up their young faces, fixed in immobile helplessness. None of them felt moved to stand up to the authority figure who was licking his chubby wounded finger.

Spinning in these minor events are different ways of playing games. They remind me of a nearly constant scramble inside words, their meanings and effects. Experience simply is what it is. Control is an illusion. Paolo usually asks that I sit back when contrasts arrive from the outside world. He didn’t want to hear about denouncing the vet, although now things have changed. Now there are good vets. At the time he said, “It’s a hassle. It won’t go anywhere. Vets are used to handling cows and horses. They have no tradition of little animals. It’s your mistake. You shouldn’t expect something.”

“If you’d listened to me,” he usually remonstrates, insisting, often correctly, that he understands one level of the Parma surface better than I. This theme has also been part of Clare’s upbringing. The words and the tone are a trap. Clare has often dived through, played in, and been overwhelmed by energies lost in the tugs, pulls, and reversals.

“I told you before you went to the vet that Fortuna needs grass. That’s all. You don’t have to pay someone to learn that. Either her coat will grow back in the spring or she has a disease too serious for anyone to save her.” Paolo reiterated his diagnosis in a didactic tone that seemed, as science is pledged to be, objective and slightly detached.

In the spring, when the shoots returned along with the violets that name a wonderful old-fashioned perfume, Violetta di Parma, Fortuna’s coat became refulgent again. Its black and white patches worked down over her naked skin. She was well. She was so frisky that she returned to climbing trees and bagging fallen baby birds. Paolo was right and couldn’t resist a boast: “If only you would listen to me,” he said, probably wishing his own life ran closer to predictable, scientific guidelines.

I felt the thousands of fractures along that needling phrase. They came in lightly, but not quite. In moments like this an introspective exhaustion invites the quiet words. I see T. S. Eliot’s exiled Prufrock turning toward the window. I hear his ineffective mumbling: “That is not it at all.” And his more terrible surrender: “That is not what I meant, at all.” Sometimes, another kind of exile pipes up and resists the tired discourse.

The fire bites. The fire bites.

Bites to the little death. Bites

Till she comes to nothing. Bites

on her own sweet tongue. She goes on. Biting.

The anger is a woman’s voice, Olga Broumas’s, from a recent American book of contemporary poetry, bringing me news from another place.