It is late March, nearly sunset. The piping squeal of our cordless telephone cuts through my English lesson at about 4:30 in the afternoon. My student, a distinguished woman in her early sixties, stops telling me in mid-sentence about her father negotiating the treaty that settled Trieste inside of Italy. The details leading up to that moment—the elite liberal education he received in Vienna, the years he spent in hiding after he, as a prefect, the chief of police, decided to let 150 prisoners taken by the Germans escape—never reach their conclusion. It’s James Gill’s youngest daughter on the phone. Her voice goes nowhere. The wind is knocked out of me. We say nothing.

He had told me. He had told others—in words and in different ways—the same thing. This would be his last year. In November he panicked because a depression overwhelmed him; he feared he might take his own life. His eyes gave out in December. His heart ticked at 40 percent the normal rate. The cortisone was turning his body into mush. Could I come a bit sooner? Once a month wasn’t enough. We had stood over the heat of the Xerox machine on the second floor of his apartment. He was mixed up, laughing, half joking, as he photocopied the same chapter twice and lost the pages he was looking for. The medicines did it, the medicines.

We were duplicating the book, a story about his grandfather from Russia and a boy who in one or two ways—brilliant, a troublemaker—resembled himself. It was a rich, learned story, funny and full of pain. It had obsessions—death first and last—and in the surge of words, thought that often reached the intensity of modern music, he might well lose track of a character. He or she would evaporate—drop from sight without letting us see motivation or feeling. Usually it was a woman. The boy character’s mother kills herself. In the pages that follow it’s as if the event has no impact on the child. She just is neatly buried. James’s mother gave him up to his father when they separated in 1930. She had taken another lover.

The look in James’s eye when he handed the manuscript over to me had none of the mischief he often called forth to make life jump. I’d been reading chapters for several years, but in the last few months he declared it coming to a conclusion. Now, over the Xerox machine, he was putting the final version into my hands. I didn’t agree.

James’s glances, if they weren’t pointed, contained wild, contiguous spiral flights of stairs. This look was, instead, indescribably still. Personal, frightened, it contained a mass of feeling: trust, self-doubt, hope that he rarely allowed himself. “It’s not true, the memoir. That’s the funny thing. It’s not my life,” he said without drawing any particular conclusion and stuffing his hands in his pockets.

We had had, after an elegant lunch, the usual—a felt (even though it was all about thought) conversation, with questions ranging from which of Schubert’s Impromptus do you prefer to what do you think about Ecclesiastes. Lunch with James was like living in a beautifully paced book. James was no longer able to read my work and ask tactful questions. The magazine had shut down years before. His interest never flagged. But his energy was measured. His manuscript absorbed the entire writer in him. Now he was rushing. We made tapes. We discussed. The whole project veered close to an abyss—an ambiguous, unsatisfying place where life and the pen have unequal weight. The man in the book was dying. But the sixty-eight-year-old man slouching on the turquoise couch, taking his glasses off and putting them on while making avid notes, was not the man in the book. The man in the book was not vulnerable enough, manic enough, searching or funny enough to be the sensitive, frail, profound man on the couch.

My life in Parma changed at the heart level without James. On the surface it was one more surprisingly terrible loss. He had never ceased helping me on my path as a writer. He was someone who held the door open. Like Picasso’s blue period, it was as if the black dreams had shown me I could not escape a specific coloring to the phase I was in. Yet I hoped I could see something in the altered, altering light. My heart would have to open to the strong, hard facts of life.

As I tried to cope, Italy zigzagged on. Craxi was accused of having traveled back and forth into France on a false passport from Tunisia, where he is in exile, unwilling to stand trial. The story came and went and never was resolved as truth or fiction. Di Pietro made the strange, unclear move of stepping down from his judgeship. It was a startling response—a crack in the defense that was going to lead Italy to a new place. Why, of course, was the question on everyone’s mind. Romano Prodi, a professor of economics from Bologna, the founder of a party called L’Ulivo, Olive Tree, demonstrated little aptitude for communication, but he gave signs of courage.

Suddenness plays a part in any life. It might be a kiss, or some drive that awakens inside and tells you that hibernation is over. A different life commences. James’s first letter accepting my poems had been like that. His death would be the same. I didn’t see change as the issue. Rather, it was an obligation to dig deeper.

The snowstorm that began as rain came up within an hour after we had released petals and blades of grass into the hole where James was to be buried. The cemetery in Montreux is venerable and un-crowded. Trees tower like passions and movements walking on air. Vladimir Nabokov, another Russian exile, is buried directly behind James. Rising up to the west slants a small mountain with a simple brown chateau on top. In front, the mirror and choppy waves of Lake Leman. The snow, in a matter of an hour, turned into a capacious blizzard. In three hours, the streets were covered, the street signs buried, the buds and trees stopped, sepulchered.

Five of us crammed into a car, after having sobbed and spoken about fragments of a life. V.’s voice had turned into a hoarse cry as he confessed, “I do not believe in God, so for me this really is the end.” As different as we were and strangers to one another, our emotions and ideas on James strangely coincided. If there is love, elements even at their most contradictory and difficult fit irreplaceably into that single being. Clare said that as she hugged me, before Paolo handed my bag up the steps of the train.

In Lausanne, we mourners were emotionally desolate. I let myself be cradled in the rocking rhythms. My father’s funeral, formal, contained except for my younger brother’s sobbing in my arms, came back deeply regretted, unexpressed, burning like a piece of dry ice. The storm’s blasts enforced the immensity of the loss. Under the tumultuous white blanket nothing could be recognized. Everything had changed. A husband and wife, inseparable friends of James’s, bickered over the directions to a hotel they knew two hours before. Their sharp, nervous comments were shorthand for how his going had set things flying loose in them. We drove in circles. James’s cousin, a red-haired woman with strong, handsome features, showed me her eyes. Their experience flashed out. They touched me, as surely as if a match had burned my skin. Early the next morning she kept me company peeling a beautiful, simple red-and-green apple at breakfast. The peel made a nice, healthy spiral. She had a terrible hacking cold. Torn because she had to leave a daughter who was waiting for a child, she had come to salute her cousin, who, from childhood on in France, had shared many fierce integrities deriving from their being Jews. During the night, a call reached her at the hotel. Her tired, grief-stricken face lifted into relief as she gave me the news. It was a girl.

I was still groping, a few weeks later; grief pushed me along in its enveloping stream. I didn’t want words. I wanted silence again. Jimmy (his French name), Jimmy (his American name), Vova (his Russian name), James, to the people who knew him as an international editor in Switzerland, and Gems, Clare’s eight-year-old spelling using Italian phonetics, were all one name—for a man who, since his Russian father had taken him from Germany to France and then to the United States, had lived inside the collisions of complicated families and parallel worlds of different languages and places he absorbed as home.

James often talked about death, so much that I would have to tell him to stop. Sometimes it was the Holocaust. When I came to edit and we had finished our work, he would often take out large old-fashioned photo albums and we would turn over page after page of handsome, intelligent, prosperous people. His aunts. Uncles. Cousins. Killed. Incinerated. Dead. We would look and look until I could look no more. The next time he would take them out again. Sometimes we stopped at photos of his ten-year-old brother, who died suddenly while he was playing with five-year-old James. Sometimes it was talk of his own disease. But then he would drop the topic and move off into more promising forms of life, usually his children and their great gifts.

James had a beautiful voice. Cortisone made it hoarse and that depressed him. His answering machine message was made on a good day. Even that clicks on in my brain.

On my walk this morning, I looked at the sun-bathed city. I need to see the sky and the drift of changing shapes. After two weeks of sodden rain, a little script of May is being written on the Parma yellows and greens.

Craxi is refusing to come back into the country to testify about his part in tangentopoli. Here, James, is a knotty problem of translation. Has the internal émigré moved? Please speak after the beep. Calling, you’d have told me what they’d said on CNN. You’d have asked me to send the Xeroxed review of Amy Clampitt that I’m going to make this morning. Although she was not one of your favorite poets, we would have talked about what was good in her work and where you found it distant and intellectual. We would have chatted about the family, and then you and I would have gone back to being readers. I have no one like you to share reading with. Not here in Italy or anywhere, really. Mandelstam said all he had to do was tell the books he had read and his biography was done. You had that as a measure, didn’t you, James?

Pietro came down unexpectedly last night. He settled in the American rocker and was willing to stay for dinner. He and I tiptoe around politics. He favors politicians who seem hopelessly on the right. It’s difficult for me to know what to talk about. The present, in general, doesn’t seem to exist between us. He can be quite happy, though, dropping into the past. He leans back. Yes. It will be the past. The conversation takes off. Pietro’s sensitivity creeps out of its shell and he begins venturing—like the unimaginable climbs he makes with ropes and picks—into space.

He laughs in a high way—almost like a donkey neighing. It’s half a laugh and half a strategy he uses to cope with the extremes that make up his experience of life. As he accepts a piece of salami, he leaps onto the topic of Nonna Rosalia—Alba’s mother. He laughs excitedly. Pietro sees her differently than Paolo. Rosalia loved Pietro best.

He looks at me. He gives Clare a caress. The world of family starts again. It is utterly unlike anything I ever imagined I would be a part of.

“You know about Venetian blinds—those slatted structures to regulate the light? Rosalia always kept them down, but with little cracks to spy through. She studied every move in the village from behind one that looked out into the square. As a child—who always jumped out of the bathroom window, running away from home—I remember her best as a talking window. She always saw me, and from nowhere an incriminating voice shot through the closed shutters. ‘Pietro, Pietro, you rascal, you brat. I see you in the square. Come in this minute. Do you hear me? You are not to be out there. Come in.’

“She believed in black magic. When there was a thunderstorm, she’d get her relics in the middle of the room and get down on her knees and pray. ‘Santa Barbara / Sant’ Simon / keep the lightning from killing me in one blow.’ ”

Paolo is warming up. Clare seems transfixed. Paolo opens up a bottle of wine and says, “It was our father’s favorite. Albana.”

“Really?” says Pietro. He drinks a glass. “It’s good.” He takes another sip. “It’s hard to face, but I can’t pretend. Papa was not a Demochristian. Ruffino told me, too; Papa was a Liberal.”

“Do you like the wine?”

“I already told you it’s good.” Pietro doesn’t like being interrupted. Like a Ferrari just reaching its running speed, he shifts upward. But Paolo is quick.

“Who were Santa Barbara and Sant’ Simon, anyway? Bogus saints unsanctioned by the church,” he interjects, answering his own question.

“They didn’t hurt anything,” Pietro says, defending Rosalia and tapping Clare to make sure she’s listening. “Nonna Rosalia and I always met head-on. It was better that way. You—Paolo—you just criticized her.” Pietro laughs loudly. This time it’s nearly a cackle. “She would beat me with a broom when she could catch me, but after that it was pari, pari—tit for tat. I would get the other end of the stick and pull it as hard as I could. We’d struggle and then—bat-ta-bang—I’d let go. Poverina. Once I dressed up like a ghost; I half knew she really believed in those things. She was sitting in her bed. Seeing the white, walking sheet coming toward her, she started to scream. She clutched at her heart, ran into the kitchen, and came back with two knives. She stabbed, trying to get me. I kept my ghost voice up and slipped out the door. Shaken, unsure if it was really me, she wrapped her head in a towel and went to bed. She had a knife in each hand.”

Paolo said, “I was four years younger, but I remember it like yesterday. I knew you were under the bedsheet, but she didn’t. She was so clumsy I was afraid she’d kill you.”

“You started to cry,” Pietro said. He laughed and went on, happy with the memories that had come alive.

“Then there was Nonna Nice. She was awful—with that roving eye slightly off-center and those lips that you didn’t want to graze your cheek. You never had to spend the night with her. But I did. Mamma was right to make us know her—our father’s stepmother. But she was horrendous. We were just used by her, when she came in the summer. She would cough in the night and call me. I was fourteen. ‘Pietro, Pietro.’ That eye would be rolling in her head, and she’d be coughing and crying out for medicine. For a good drink of spirits. With those awful lips. I could fake it. I could be kind, but she was frightening. It was a lot to help an old lady like that. You never knew, really, if that horrible coughing sound might be her last.

“Nonna Rosalia, on the other hand, I cared for. She, too, had her crisi—day and night. Her heart. She couldn’t breathe. She needed a scoop of cherries soaked in brandy. She had a great palate. Do you remember how in Castelnovo in those early years Mama rented out our rooms and we crammed into Rosalia’s rooms in the summer?”

“They were horrible,” Paolo said. “Her rooms.”

“You’re wrong,” Pietro said. “They had a nice cotto floor. Good light coming in the windows. It was the renters who had complications. One didn’t get a kitchen, the other a bath, but so what? Remember that woman who set fire to the curtains? She’d had a story with a priest. She’d been sent to the mountains, through the church’s network, to get her life back together. Mamma was picked as the person to give her shelter for free. She fell asleep smoking and burned up the only special thing in the room: the heavy curtains Rosalia loved.”

“What’s your first memory, Pietro?” I ask.

“I don’t know for certain. I think a tree trunk—large, solid. I remember leaning against it. Otherwise, but I don’t know if it’s really mine, I remember being brought home from a farmer’s house where Angela and I had slept. We had scabies. My poor mother rushed us into the bath, while trying not to criticize the farmers. I remember seeing the fixtures for turning on the water and screaming with fear. I never, even as a small child, was one for a civilized, confining way to live.”

When Pietro leaves, we’re all in a good mood.

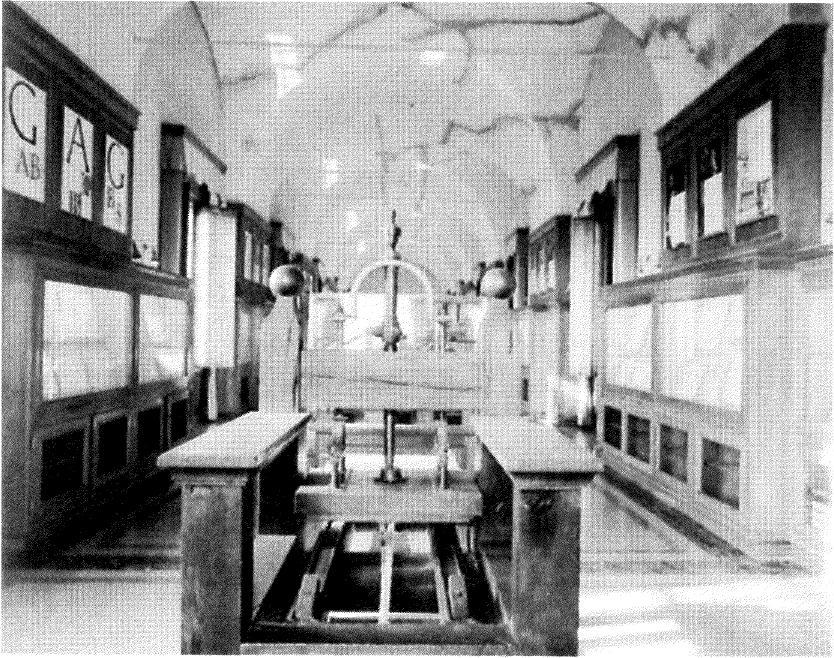

Bodoni’s fame was such that the dukes hired him to run a ducal printshop and allowed him to have private business