Your Medical Checkup

■ ■ ■

We’ll do our best to keep this medical section as quick and painless as, well, not going to the doctor. You already did most of your medical heavy lifting in Level 1 when you learned about organizing your doctor and specialists (see here). Now it’s time to focus on your actual health in a way that’s helpful and not too overwhelming for your family to understand.

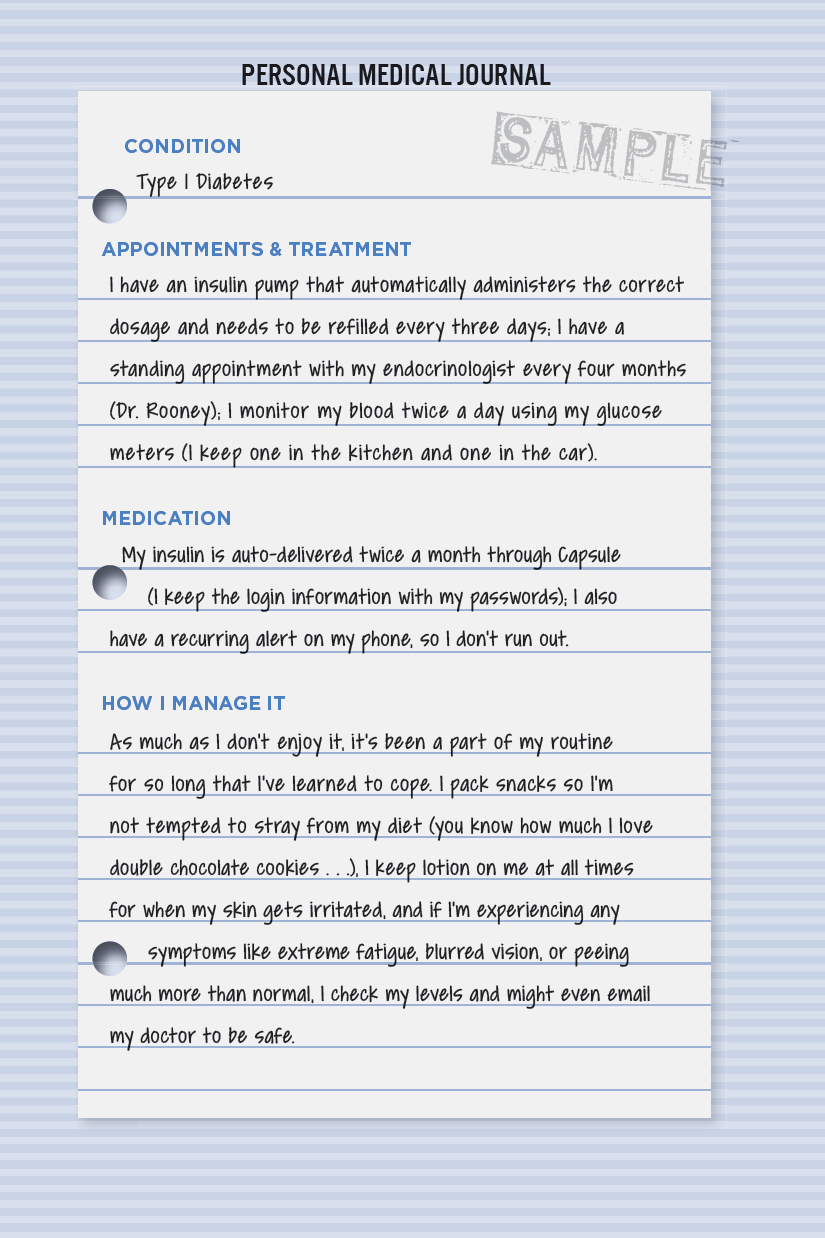

Your Personal Medical Journal

Talking about medical problems is rarely fun. People tend to downplay the bad stuff because they don’t want anyone to worry. How many times have you heard a variation of the phrases “I’ll get to the doctor when I have time” or “I’m doing everything they’re telling me to do” only to find out later neither is true? Medical problems combine many of our biggest fears: the possibility of a dire diagnosis, having to make extreme lifestyle changes to get our health back on track, and facing our own mortality.

Ideally, a person dealing with all these traumatic issues at once would be open and honest with the people they love. In reality, they often keep their health conditions a secret until it’s too late. On three different occasions, one of our coworkers found out about surgeries his parents had after the fact. (They said they didn’t want to worry him or his siblings, but it had the opposite effect.) If you’re facing an illness, it’s important to ask for help, no matter how hard that is. If you’re tasked with helping someone else face an uphill battle, try your best to be as supportive and delicate as possible. These might be the last few years, months, or days you have with someone you love.

But since we’re here to help you get your life organized, forget about everyone else for a moment. The best way to keep track of your own pressing or personal medical issues—and provide a definitive record for those who might need it—is with a Personal Medical Journal.

Unlike medical records, which are cold, clinical, and filled with lots of jargon, this is a more casual and realistic way to keep others in your life apprised of your health. Like the way we helped you understand how to create a Home Operating System (see here), it’s quite simple. But instead of walking around the rooms of your home and making notes, you’ll be taking a tour of your body.

Start by listing existing or current conditions. Anything that you manage on a regular basis, or that involves treatments, should rise to the top. Any low-maintenance chronic condition that simply flares up from time to time sinks to the bottom. Think of each issue as an item you’re writing on an index card and then pinning to a 3D rendering of your body. An example of the template can be found on the next page.

Even if you don’t adhere to our exact format, try to include as much detail as possible and don’t forget about any related medical documents or records (if they can be accessed via an online portal, include the login info with your passwords) and equipment that would need to be returned to avoid a huge bill from the insurance company (including the type of device, make/model, and equipment provider).

Voilà! You just helped someone easily understand one of your important health conditions. You can do this for everything like kidney problems (dialysis), high cholesterol (medication/diet), heart conditions (pacemaker and stents), autoimmune diseases (arthritis, multiple sclerosis, lupus), hearing loss (hearing aids), or anything else that ails you.

Start from your head and work your way to your toes and categorize the conditions based on level of urgency. If you think they’re all of equal importance, do it alphabetically. Your journal can be a digital document or handwritten, though we suggest digital so it’s easier to update and share. The method doesn’t matter.

Next up are chronic problems that aren’t life threatening but still something you have to manage. This might include allergies (unless they’re life threatening, in which case they should go with the preceding important conditions), migraines, irritable bowel syndrome, past injuries that affect your walking or range of motion, eyesight issues (glasses prescription, cataracts), and anything else that would be helpful for your family or doctors to know. Use the same template and go from head to toes again (or toes to head if you want to mix it up).

Finally, it’s time to organize something that can be an actual lifesaver for those you love: your family medical history.

Do women in your family have a history of breast cancer? Do the men have a history of prostate cancer? Do you know of any heart or respiratory problems, blood disorders, muscle or spine conditions that may be hereditary? It’s common for parents to tell their kids about these problems, but they can easily be misunderstood or forgotten. Perhaps something that affected your grandparents and skipped a generation could be completely preventable and treatable if you catch it early.

We glossed over your official medical records, but you should share those as well by filling out a HIPAA authorization form—ask your doctor for one or just Google it and download—which allows someone you trust to view them. The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 was created to make your medical records easier to access while also protecting your privacy. Like everything involving health care, it’s mind-numbingly complicated, but it’s helpful for adult children caring for their parents and parents whose kids are going to college.

Plan of  Attack

Attack

Construct Your Personal Medical Journal

Gathering Records

Time: Two to three hours if you use the method and template we’ve provided (see the facing page) to document all of your current ailments and general medical history. Add an extra two hours to complete a family history, since you may have to research this information. We suggest using a digital document to keep track of everything, but a handwritten journal works too (just keep it up to date, please).

Advance Health Care Directives

When you can’t make health decisions for yourself, this is the North Star that guides your loved ones and doctors in the right direction. It might sound like an 1980s action movie—Advance Directive, starring Sylvester Stallone and Bruce Willis!—but it’s really the universal term for how you’d like to be treated in the event of a medical emergency or at the end of your life. It’s made up of two parts:

Naming a Health Care Proxy: This person advocates for your care when you can’t. We call it a Proxy, but it can go by different names such as Health Care Power of Attorney or Medical Power of Attorney (not to be confused with the financial/legal Power of Attorney), Health Care Agent, Representative, or Surrogate.

Filling Out a Living Will: This spells out the types of medical treatments you do or do not want during a major medical emergency or toward the end of your life.

The bulk of the effort you’ll spend when filling out these documents will be devoted to decision making. These decisions are not really all that pleasant to think about, but they’re much easier to make now than when you’re in a hospital connected to tubes.

Why You Need an Advance Directive

In the event of a medical emergency, things move really fast, and regrettable decisions can be made. An Advance Directive helps eliminate some of those regrets before they happen. Emotions always run high during stressful situations, but if you prepared this document outlining your wishes during a more peaceful time, it can cut through the emotional haze and provide a clear direction. Finally, if you don’t make these decisions, you’re forcing someone else to bear the burden and live with it for the rest of their life.

How to Choose a Health Care Proxy

If you become incapacitated and can’t speak for yourself, you’ll want someone you trust to speak on your behalf. This person needs to know what types of treatments you want, will stand tall in the face of adversity (namely, pushy doctors and pesky family members), and will make sure you get the care you want. Enter your Health Care Proxy. But before you settle on someone, it’s important to understand what they’ll be able to do.

For starters, they can make choices about your medical care and pain management. This includes the ability to request or decline life support treatments, medication, or surgical procedures. Your Health Care Proxy can also decide where you can seek medical treatment, including moving you to different facilities. They can view and approve the release of your medical records and apply for benefits on your behalf, including Medicare or Medicaid. Finally, they can take legal action on your behalf to ensure that your medical decisions are honored.

Now that you understand the power of a Proxy, here are the characteristics you’ll likely want in whomever you choose. They should be a person you trust implicitly and one who understands your values. They should be someone who has a clear understanding of how you want to be treated in a medical emergency. And your Proxy should be willing to follow your decisions, even if they don’t agree with them or are put under pressure from family or medical professionals.

Finally, your Proxy needs to have endurance. Their responsibilities could drag on for weeks, months, or even years. Your choice might be a member of the family, a lifelong friend, or an associate you feel will put emotion aside and stick to what you want. You want someone who will remember that these are your decisions, not theirs, and will always act accordingly, even if things get tough.

TIP: You should also choose an alternate or secondary Proxy in case your first choice is unavailable during an emergency.

Tell the Proxy They’re the Proxy!

When you choose someone, it shouldn’t come as a surprise to them.

There was an episode of Grey’s Anatomy where one of the doctors was clinging to life after being electrocuted, leaving the rest of the staff with two options: let him die or do a risky procedure that might kill him. When the nonelectrocuted doctors consulted the electrocuted doctor’s Health Care Directive, they learned, to their shock(!), that he had named Meredith Grey as his Proxy. (For those who don’t watch, she’s the star . . . hence her last name being the clever play on words in the show’s title.) When Dr. Grey found out, she was stunned.

“But he can’t make me next of kin without talking to me first,” Grey says.

Oh, but he can, Dr. Grey. And he did. We forget how the episode ended. Maybe he lived, maybe he did not. Maybe two attractive doctors started making out and the credits rolled. The point is, it’s possible for you to be a person’s Proxy and not know about it until you’re the final word on whether they live or die. This is fine for a prime-time drama, but a terrible thing in real life.

The first rule of naming a Proxy is that you need to tell them well in advance that they are your Proxy. The second rule is that you should have an open and honest conversation with them so they know how you’d like to be treated and the types of care you’d like to receive. It could be that this person isn’t the right fit. What if they’re unwilling to pull the plug even though that’s what you want? What if they’re all too willing to pull the plug when you want to be kept alive no matter what? Better to get this all sorted out well ahead of time.

Although it might be difficult to share these decisions with your family, it’s important to do so to avoid confusion. It’s possible that some family members won’t understand the choices you’ve made and may even try to talk you out of them. Stand your ground and let them know this is about the medical care you desire. Tell them these aren’t easy decisions to make, you want their love and support, and you will offer them the same consideration for whatever they choose for themselves.

Living Wills

Think of a Living Will as an emergency medical treatment checklist for the important players in your life. Your doctors will use it as a guide to manage your care, and your Health Care Proxy will use it to make sure what you want is getting done.

What a Living Will Is (and Is Not)

If you’re worried that a Living Will gives medical professionals permission to kill you, you’re being way too dramatic. (Perhaps you should try out for a part on Grey’s Anatomy?) Living Wills are primarily about life-support treatments, specifically if you’re suffering from a terminal or progressive illness or a major accident where you’re unlikely to recover. A Living Will is used only if you are deemed incapacitated and mentally incompetent by at least one doctor. Even then, it can be overruled if it jeopardizes your care.

Evaluating Life-Support Treatments

All life-support treatments have pros and cons—something we may have learned when COVID-19 made ventilators front-page news. For each treatment, consider the following questions, which you should go over with your doctor if you have concerns.

What Happens If . . . You Don’t Have a Living Will

Those of a certain age in the 1990s and early 2000s probably recall the name Terri Schiavo. When Schiavo was twenty-six, she had a full cardiac arrest. After she spent eight years on life support, doctors determined she was in a persistent vegetative state, and her husband got a court order to remove her feeding tube.

Her birth family believed she was still conscious and fought to have the feeding tube reinserted. For the next seven years Schiavo’s husband and family fought in court. The battle even reached the highest level of government when President George W. Bush signed legislation to keep Schiavo alive. Eventually, the original decision to remove the feeding tube was upheld, and Schiavo died in 2005.

Regardless of which side you believe was right, if Schiavo had created a Living Will, it could have eliminated a lot of heartbreak for all involved. It would have prevented her husband from getting pitted against her family, and the final decision would’ve been hers alone.

The only upside to this highly upsetting and divisive moment in history was how it made Advance Directives front-page news, waking millions to the importance of creating one, regardless of age. If you don’t have a Living Will, the default course of medical treatment is almost always to do everything possible to keep you alive at all costs. Or to force your family into making the call to suspend treatment and live with that decision for the rest of their lives.

To save the people you love this agony, all you have to do is make your choice clear in a Living Will. The only bad decision in this case is none at all.

LIFE SUPPORT What It Does to (and for) You

The following are the most common types of life-support treatments, how they work, and their possible side effects. Please bear with us. We’re fully aware that this part isn’t much fun.

❏ What purpose does the treatment serve?

❏ What are the side effects?

❏ What type of medical equipment will be used, and how will it affect my body?

❏ Does this treatment usually improve my overall health, or does it simply extend my life?

Additional medical forms that aid people closer to the end, specifically a DNR and POLST, are covered later (see here).

Where to Store Your Advance Directive

An Advance Directive isn’t one of those documents that requires privacy or discretion. You shouldn’t keep it locked in a safe or hidden away in your secret fortress of solitude. For it to be of any use, it has to be available when it’s needed. And you never know when it’ll be needed, so here are some suggestions:

TIP: Play it extra safe and also store a digital copy in a shared folder or an online platform, be it a health care portal or a site like Everplans. Although it’s always preferable to have the physical copy, this digital version can still be handy in a pinch.

1 Keep it with other important household documents (emergency contact list, Wi-Fi password, Home Operating System, Personal Medical Journal).

2 If you’ve been experiencing health problems, keep it on your fridge or someplace in plain sight; you should also keep a copy in your car, since many unexpected medical emergencies are the result of an accident.

3 Give a copy to your Health Care Proxy.

4 Give a copy to your doctor.

Visit Your Advance Directive Every So Often

Once you have an Advance Directive, review it periodically to think about whom you named as your Proxy and to verify you’re still on board with all the decisions you previously made in your Living Will. Things change over the course of your life—people move (and pass) away, and you may have a change of heart about certain medical treatments—so always keep everything as current as possible.

SECOND LIFE: Donating Your Organs

You don’t need to wear spandex, see through walls, or have a billion-dollar suit of armor to be a superhero. All you need to do is become an organ donor.

Many people view organ donation as a final altruistic gesture to help others, and almost all religions support it. Every state has its own donor registry; if you’ve registered through your local Department of Motor Vehicles, you may get a sticker or some other sign on your driver’s license identifying you as a donor. As long as you do it in some form, you’ll be in your state’s donor registry.

It also appears as an option on most Advance Directive forms, offering another shot if you never did it through the DMV or a state registry. You may want to tell your family, your Health Care Proxy, and your doctor you’re a registered organ donor so they can support your decision to donate.

How the Donation Process Works

Here’s some background so you can sound well versed on the topic if it comes up at a cocktail party. And what cocktail party is complete without a discussion about giving away your organs?

Organ donation in the United States is regulated by the nonprofit Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network, which is administered by the United Network for Organ Sharing under contract to the US Department of Health and Human Services.

If you have a fatal accident or illness and are admitted to the hospital, your family or your Proxy will tell the hospital team treating you that you’re a registered organ donor, which can help them prepare.

What Can Be Donated?

Think of this as a menu of lifesaving (or life-improving) goodness.

ORGANS: Kidneys, heart, lungs, liver, pancreas, intestines

TISSUE & OTHER VITAL BITS: Corneas, skin, heart valves, bone and cartilage, veins, tendons and ligaments

How far in advance do you plan vacations? A few months, usually, right? You book the flights and hotels, arrange for time off from work, get the kids out of school, and start looking forward to it from the moment you make the final arrangements. We view eldercare in this same anticipatory light because it’s never too early to think about how and where you want to live when you’re older.

Granted, the circumstances may not be very vacation-like. You could be having trouble getting around and taking care of regular daily activities (like cooking, cleaning, and driving) or become ill. But you don’t have to wait for something to happen to start getting a handle on your options.

Things to Consider Right Now

Take the following things into account when preparing yourself mentally for decisions you, or your family, will need to make:

Health: Will you need doctors and nurses on staff to help with any medical problems? Even if you’re not ill, perhaps you want easy access to medical professionals, just in case.

Finances: Do you have the means to live where you want, for as long as you want? Did you even read what we wrote about how expensive Long-Term Care Insurance can be on here? (It’s OK if you didn’t. You can always go back. It’s not going anywhere.)

Location of Family Members: Do you want to be near family and friends, or will they travel to you?

Degree of Independence: Do you like doing things on your own, or are you OK with someone else pitching in and helping out with your daily routine?

It’s hard to predict all of these things in advance. No one likes to picture themselves as anything other than able-bodied and healthy. But knowing what to expect and preparing yourself and your loved ones for different possibilities is an achievement in itself.

Three Types of Eldercare Housing

In-Home Care: This option is for those who want to continue living at home (and who doesn’t?) but may need some help with daily activities like cooking, cleaning, and hygiene.

This level of care may require some modifications to your home to reduce the chance of accidents and make caregiving easier—like installing ramps for a wheelchair, widening doorways, installing a stair lift, and adding railings in the bathrooms and shower.

Cost: This can vary greatly, depending on your current living situation and the level of modifications needed for your home. Although this is probably the preferred option for many, it also has the most variables, especially as your health declines.

Assisted Living: This option is best if you can manage your own care but need occasional help with daily activities, such as cooking, cleaning, and other routines that might become difficult to do on your own.

Although this type of care moves you out of your home, you can still have a healthy degree of independence—like living in a small apartment—with the added benefit of having doctors and nurses on staff at all times.

Cost: Assisted-living facilities generally require a down payment and monthly fees that range from $1,000 to $5,000. The costs vary based on location, size and style of the room, and services and amenities offered. Medicare won’t cover the cost, though some facilities accept Medicaid, as well as Long-Term Care Insurance (again, see here) and HMO/managed care plans, but you’ll have to pay the bulk of the cost out of pocket.

Nursing Home: This is for those who need a high level of medical care—there are doctors or nurses on the premises at all times—in addition to help with daily activities.

Cost: Since nursing homes provide the highest level of care, they’re also the most expensive, averaging around $6,000 per month. To lessen the financial burden, Medicare covers short-term stays (usually about 100 days) and Medicaid might cover the costs (you have to qualify, and not all homes accept it). If you don’t have the financial means, you’ll need a large savings account or generous family member willing to foot the bill.

In the Autumn of Your Life: It’s understandable to want to ignore the fact that all humans eventually need some type of care. It’s also not an easy conversation to have with your family, especially if every time you try it ends with a vague “We’ll figure it out when the time comes.” You may think one of your kids will take you in and set up a cozy room, but what if they can’t?

The key is to face this head-on, know your options, and work toward getting a financial plan in place. Preparing today can help you stop worrying about tomorrow.

No, You Won’t Be Killed for Your Organs

If you’re worried that doctors will let you die so they can put your parts into another human, that won’t happen.

The hospital needs absolute confirmation that you’re brain dead before moving ahead with the donation process. To determine brain death, a neurologist will perform a series of tests (often more than once) to see if there’s any brain activity. Brain death is not a coma. It is, in fact, death. If there’s no brain activity, the death will be confirmed by a neurologist and the body will be kept on life support to maintain the organs until they are removed.

At no point will your care be compromised. This isn’t a Lifetime movie where a doctor wants to harvest your kidneys to save his dying son. This is real life where medical professionals keep you alive at all costs. Once that’s no longer an option, donation becomes a chance to save others.

There’s Never Enough to Go Around

We’ve come across countless donation stories where a family turned the worst day of their lives into a positive force in the world. Whether it was the eleven-year-old boy in China who succumbed to brain cancer and donated his kidneys and liver or the sixteen-year-old football player whose sudden death ended up saving his own grandfather with his kidney, these stories of tragedy have become symbols of love and hope.

According to OrganDonor.gov, there were more than 113,000 men, women, and children on the national transplant waiting list in 2019, and twenty people die each day waiting for a transplant. If you still have reservations, please reconsider because it’s the best gift you can give.

Plan of  Attack

Attack

Making Big Decisions

Time: Around a minute to download your state’s form (incasethebook.com/advance-directive-forms); an hour to understand the decisions you need to make if you’re already sure of what you want. And if you’re unsure and want to speak with a doctor, bring the form along to your next appointment.

Cost: Free if you do it yourself; a fee if you do it with an attorney as part of an estate planning bundle.