Nothing is so contagious as example.

FRANCOIS DE LA ROCHEFOUCAULD

I’ve written about hope from time to time, perhaps because I want so desperately to feel it, to have it stop wriggling away from me when I try and pin it to the mat. Hope is your best club in golf, the hope that on the next shot this stupid little white thing will do what you ask it to, that maybe a miracle will occur and you’ll be there to see it.

You need hope in golf; you need it even more when you have three teenagers. Lately I’ve been praying that these kids will stop grumbling and yelling at each other. That we’re not raising complete pagans here. That they will encounter godly people who are full of hope. After all, most of us would rather see a sermon than hear one any day.

My prayers have been especially earnest when it comes to our younger son, partly because he reminds me of myself at his age—filled with mischief and always about three seconds from a very bad decision.

Jeff is a big, tough, stylish kid, handsome and strong, the teenager all the little kids love and the kind girls phone to discuss math problems with (or at least that’s what they tell you when they finally get past your customer service department). His laugh was enough to bring the house down when he was a kid, but that contagious laugh began to vanish by the time the boy was twelve and was completely extinct when he turned thirteen. It’s a horrible thing to watch someone view life wearing the glasses of a teenager, trading in joy because it isn’t so cool.

Our kids have always laughed a lot, partly because they get their sense of humor from my wife’s side of the family, whose motto is this: “It’s all funny until someone gets hurt. Then it’s hilarious!”

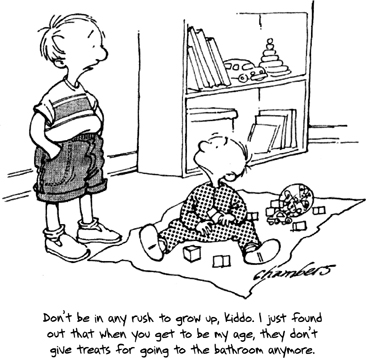

I slip on an icy sidewalk, landing on my rear, and these kids will snort and laugh until they hyperventilate. I raise a window to get some air in the room and it slips, landing on my fingers, and they fall off their chairs laughing. But by the time they are teenagers the hyperventilating has pretty much been cured. Life is as serious as a cracked rib. If childhood is spring training, the teen years are extra innings in the World Series. Laughter seems out of place, like a puppy at church.

And so I worried about Jeff’s dislocated funny bone, because laughter is surely one of God’s purest gifts to us. How I longed to hear that laugh again. The only time it seemed to eke through was during a movie I wouldn’t necessarily recommend or when I hit my elbow on the back of a chair. I even wrote the word on a prayer list I keep for each of my kids—laugh—believing that God cares about these things as surely as He cares for the other requests on the list: respect, soft heart, attitude, that my son will find a godly wife in about ten years.

To complicate things, the boy was struggling in school. He was late on assignments as often as United Airlines. A teacher called to tell me this and to hint that if he could issue marks below zero, he would give them to my son. Imagine telling your friends you have a minus twenty-three in Chemistry. Not an F, but an H.

My prayers turned more urgent. At night I closed my eyes in the dark and tried to pray, but the whole thing seemed so hopeless that I would get up and turn on CNN. There I found a strange relief knowing that things were at least as awful as I thought. Maybe worse. That the sky really was falling, that situations were bad everywhere, that the good guys were in the minority. Sometimes, if things grew really desperate or I couldn’t find the remote, I would open my Bible.

I received a welcome phone call in the midst of all this. It was Compassion, the international child-development agency, asking us to go to the Dominican Republic on a short mission trip. I prayed about it for one-third of a nanosecond, then eagerly said yes. I would run away from home. And take Jeff along.

The teacher caught wind of our escape plans and called to accuse me of taking leave of whatever senses I had left. I thought of something I’d read about the Cuban Missile Crisis, how the Kremlin sent two messages to President Kennedy. One was hostile, the other calm. Kennedy said, “Let’s respond to the saner message,” and as a result, those elementary school drills where we cowered under our desks in panic were all in vain. So I listened for the saner message. The teacher said I was neglecting what’s truly important by taking Jeff out of school, that he should be at home with his teenage skull buried in serious books.

I considered telling this teacher that I learned about 6 percent of what I now know in the classroom, but thankfully I went with a saner response. I am a Christian, and sometimes I am relieved to find myself acting like it. “I’m so glad you care about him,” I said, “but I’m really concerned about his spiritual health.” I did not say, “I don’t want his schooling to interfere with his education.” I’m thankful I didn’t.

That night I waved the plane ticket in front of Jeff like a carrot. I told him that he’d better smarten up, listen up, and catch up on his assignments, or I would give the ticket to a complete stranger, maybe even the next girl who called. He smiled ever so slightly. “Do your assignments,” I told him. The smile was still there when he promised he would.

We were met at the airport in the Dominican Republic by Pastor Bernard, who has a glow about him like he works at a nuclear power plant. Bernard doesn’t say a lot, which is one of the first signs of sainthood. Mostly he grins, like he knows something you don’t. People ask him why he’s grinning, and he tells them, “Peace. Joy. Hope.” And they want to know more.

Bernard speaks three languages fluently, but he’d rather listen to you. Jeff latched on to him during those ten days. He listened to Bernard’s stories of God at work. He watched Bernard tell others of Jesus. And better yet, he saw God for himself—through Saint Bernard.

We stood in a village devastated by a hurricane, but Bernard’s face was beaming. “They want me to tell you that their houses are gone but it’s okay. The church is still standing.” The crowd smiled and nodded. Jeff kicked at a rock and shook his head. We saw children who subsist on food they’ve scrounged from the dump, kids with hollow eyes and bloated bellies. We helped feed them and saw what child sponsorship can accomplish. When we said good-bye, it was amid tears and ample hugs. Jeff hugged Bernard.

“I’ll miss you,” said Bernard.

“Me too,” said Jeff.

If you were to ask me about my happiest moment of fatherhood, I might mention the night soon after we returned. Jeff’s marks were up a little, hovering near the passing mark. I hadn’t heard him fight with his sister or grumble about a thing. Not yet. And the laughter was back—not the hyperventilating kind, but his vital signs were good. He was making himself a snack in the kitchen along about midnight, and I could smell it from our bedroom, so I crept out to see if he would share.

The boy had cracked half a dozen eggs into a bowl, along with a pound of shredded cheese, and thrown an entire package of Canadian bacon into a sizzling frying pan. As he stirred the eggs and cheese together, he said to me, “Dad, I’d like to sponsor a kid in the DR. It’s thirty-five bucks a month, right?”

I tried not to let him see my tears, then decided it didn’t matter. I’d just watched my son go from talking about Christianity to doing it. From following those who follow Jesus, to following Jesus for himself. I guess hope always catches us a little by surprise.