Modernity’s Sylvan Subjectivity,

from Gainsborough to Gallaccio

Catherine Bernard

Modernity has been a fiercely contested category for a long time now. And to consider this a truism has become something of a truism too, as if any discussion of modernity was of necessity trapped in a form of belatedness. That sense of critical infinite regress has often been seen as analogical to modernity’s conflicted relation to its own present, as is evinced in Nietzsche’s Untimely Meditations, Derrida’s Specters of Marx, Bruno Latour’s We Have Never Been Modern, or more recently Giorgio Agamben’s 2008 essay ‘What Is the Contemporary?’ And Freud’s concept of Nachträglichkeit is of course of strategic import here for the way it unhinges the subject’s sense of self-presence in time.1

Similarly, the eurocentrism of modernity has been the object of systematic deconstructions, a task pithily summed up by the Argentinian-Mexican writer Enrique Dussel in his 1992 introductory Frankfurt Lectures:

Modernity is, for many (for Jürgen Habermas or Charles Taylor, for example), an essentially or exclusively European phenomenon [. . .] I will argue that modernity is, in fact, a European phenomenon, but one constituted in a dialectical relation with a non-European alterity that is its ultimate content. Modernity appears when Europe affirms itself as the ‘center’ of a World History that it inaugurates: the ‘periphery’ that surrounds its center is consequently part of its self-definition.2

Postcolonial studies and connected history have of course contributed to our understanding of the way modern eurocentrism is locked in with its dark and repressed other. As Edward Said cogently argued, there would be no Mansfield Park – I will return to Austen later – without Sir Thomas Bertram’s West Indies sugar plantations. As Terry Eagleton also contends, the forces of social and economic mutation at work in Wuthering Heights need an alien within – Heathcliff – to be fully unleashed.3 As Sanjay Subrahmanyam also shows in his 2011 Three Ways to Be Alien: Travails and Encounters in the Early Modern World,4 the budding of an inchoate European identity in the Renaissance needed the construction of unheimlich encounters on the borders of Europe.

European modernity is thus often constructed in agonistic terms, even when the alien nestles within that modernity in the making. Fallen women, foundlings, colonials must be dealt with and expelled for the system to adapt and survive. The Marquise de Merteuil must be disfigured by smallpox for Choderlos de Laclos’s ambiguous Liaisons dangereuses to fulfil its allegorical agenda. Little Jo in Bleak House must die for the redemption narrative to fully work. The same sense of a conflicted modernity is to be found in philosophical accounts of modernity, from Adorno and Horkheimer to Bruno Latour and Jean-François Lyotard. The repression and foreclusion of otherness has thus been read as unavoidable to a system inherently binary rather than dialectical,5 as if the dialectics of Enlightenment was bound to be negative; and we know how the modernist project reappropriated the power of negativity to radically subversive ends.6

Understanding the European mind in its relation to modernity may require a less aporetic approach to the dialectics of the modern, one less overshadowed by the power of Lyotard’s differend7 and his conviction that modernity has bred incompatible phrase regimes. Reintroducing the possibility of a sublation of the inner tensions of modernity would imply reading the modern in a more poietic vein, one which would perceive modernity as an ongoing practice, self-critically open to paradox and contradiction; an approach, in other words, less indebted to an absolutist definition of the modern and more atune to the productive potential of concepts once we agree that their reversibility may also have a hermeneutic effect. The emphasis on the hermeneutic productiveness of the approach – as opposed to a heuristic reading of the modern – cannot be too much emphasised as such attention to the poietics of tension entails a work, a task, rather than a revelation.

Such attentiveness to the power of paradox was one of Michel Foucault’s most fruitful contributions to the genealogy of the modern. In his essay ‘What Is Enlightenment?’, first published in The Foucault Reader and which reworks an unpublished manuscript, Foucault redefines the Enlightenment as opening the possibility of a critical ethos working with or from within its inner contradictions. Rereading ‘Was Ist Aufklärung?’, a text published by Kant in the Berlinische Monatsschrift in 1784, Foucault rethinks the spirit of Enlightenment as an ongoing practice in self-definition, a discipline that would be no disciplining subjection but an exercise in dialectical criticity. For Foucault, modernity is not a historical moment but an ‘attitude’8 that is endlessly reactivated and which must contend with its inner splits, so that modernity should not be established as an absolute, requiring an other to assert itself, but as self-divided or, even more accurately, as a practice.

As one might expect from Foucault, such ethos is profoundly immersed in the material reality of historicity, and should be ‘described as a permanent critique’ of our historical being.9 Here Catherine Porter’s translation of Foucault’s original text entails an intriguing misprision, choosing as it does to refer rather to ‘our historical era’. Such misprision would no doubt warrant a full volume specifically devoted to what is culturally repressed in translation. Foucault’s original text precisely refuses to narrow down the historical perspective to a specific context. In the original, that ‘attitude’ is not of a given place and age and cannot address ‘our historical era’. It is precisely beyond place and age. It engages what Foucault defines in fact, as our ‘être historique’:10 our historical being, a form of historicity beyond the here and now of any specific ‘historical era’. Such a transcension of history by historical criticity comes as no surprise if we remember Foucault’s deep interest in Nietzsche’s visionary dehistoricising of origins and his ‘untimely meditations’: I am referring here to Foucault’s 1971 essay ‘Nietzsche, la généalogie, l’histoire’, also reprinted in the same reader. For Foucault, modernity’s critical ‘attitude’ needs no other. The other, as defined by disciplinary order and as relayed by the symbolical imagination, lies within. Modernity’s criticity ‘consists of analyzing and reflecting upon limits’.11 But those limits are not external to modernity and modernity’s criticity lies in the possibility of their ongoing ‘transgression’.12

OF TREES AND MEN

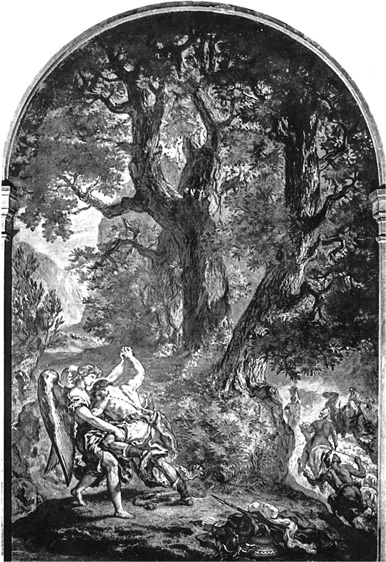

Modernity’s internal dialogue with the other entails a dialectics which has been the subject of many a work of art. From the start, nature has embodied that otherness within; and we should not be surprised that a Romantic painter like Delacroix should have devoted such a large part of his fresco, Jacob Wrestling with the Angel, in St Sulpice church (Paris), to the vision of a mysterious, timeless nature, seemingly indifferent to the momentous fight taking place (see Figure 3.1).

Figure 3.1 Eugène Delacroix, Jacob Wrestling with the Angel (lutte de Jacob avec l’ange), 1861, Chapel of the Holy Angels, St Sulpice church, Paris, © Emmanuel Michot / COARC / Roger-Viollet

The trees that dwarf the two protagonists of that dance-like struggle offer an enigmatic backdrop to the visual transcription of Genesis, chapter 32. An extension of the Angel’s divine power, the trees also resist our temptation to read them only allegorically. Absent from the biblical source, they exist as and for themselves. In this late work of Delacroix’s, they above all provide a wonderful terrain of experimentation with textures, colours and hues. They paradoxically look back and look forward. They rehearse the vision and manner of the Dutch landscape painters, of Nicolas Poussin and Claude, a vision that Constable and Gainsborough had already appropriated, in order to experiment with vision and texture. They also anticipate with later experiments with texture. They belong to the history of artistic modernity, as much as they belong to the history of visual allegory.

The critical modernity of Delacroix’s trees lies in this paradoxical relation to the history of visual representation. Delacroix’s reiteration of the sylvan motif captures something of a mute enigma; an enigma that is inexhaustible and incommensurate, that cannot be explained away by the art of quotationality and that calls for renewed instanciation, again and again and again. Painted on the eve of nascent modernism, Delacroix’s work captures modernity’s ‘attitude’ at its most critical, when it pushes against the limits of representation, a tension that was, as we know, to be foundational to modernism’s poetics of othering.

The context might be widely diverging but the end of The Great Gatsby also dramatises such a moment of criticity. Nick Carraway returns to Gatsby’s house and walks down to the beach. He is, at that point, invaded with a vision of a sylvan world both elemental and mythical, a vision of ‘the old island [. . .] that flowered once for Dutch sailors’ eyes – a fresh green breast of the new world’.13 The sylvan world he imagines is inscribed in the allegorical metatext of historical predestination: ‘Its vanished trees, the trees that had made way for Gatsby’s house, had once pandered in whispers to the last and greatest of all human dreams.’14 Yet this world, from the start, resists all ideological subsumption. In front of it, consciousness is caught in a form of syncopation which the text necessarily aestheticises, yet immediately forecloses: ‘man must have held his breath in the presence of this continent, compelled into an aesthetic contemplation he neither understood nor desired, face to face for the last time in history with something commensurate to his capacity for wonder’.15 The sylvan universe conjured up by Fitzgerald is a liminal universe that produces a limit-experience. That experience is both intensely modern in its collusion with imperialism and already foregone, past, vanished, both intensely new and already archaic, both utopian and nostalgic, but nostalgic of a sense of belonging European man had not even intuited before.

Fitzgerald captures something here of the untimely criticity of modernity as a practice working against the limits of its own laws and desires. In the visionary eclipse of the trees, he also intuits the two dialectical modalities of Europe’s modern mind. Pristine nature is soon to vanish, to be rationalised, yet it endures as the negative spectre of instrumentalised nature. The trees confronting the Dutch sailors thus embody the two modalities of man’s relation to nature in the modern age. As a force soon to be subjugated, it already bears the mark of instrumental and experimental reason; as a repository for man’s ‘capacity for wonder’, it also puts instrumental reason to the test of desire. Simon Schama’s pithy definition of modern England’s relation to nature: ‘The greenwood was a useful fantasy; the English forest was serious business’16 should in fact be reversed: ‘The English/American forest was soon to be serious business; but the greenwood was a useful fantasy.’ The vanished, visionary trees of America’s ‘fresh, green breast’ push modernity’s phenomenology to its limits. The new, imperial subject in the making can only experience himself as a historical/feeling subject, a subject whose reflexive expertise is grounded in an experience that is both rational and sentient, disciplined and unheimlich.

EXPERTISE AND SUBJUGATION

Eco-history has shown how European demographic expansion and European expansionism resulted in massive deforestation and the development of forestry,17 timber being a material strategic to Europe’s imperialist agenda, as early as the Renaissance period.18 Taking up Kant’s and then Foucault’s question, ‘What Is Enlightenment?’, in his masterful study Forests: The Shadow of Civilization, Robert Pogue Harrison answers: ‘A question for foresters.’19 Of course, as Harrison also shows, such entanglement does not date back to the Enlightement; it is inherent to civilisation itself, at all times, everywhere. As Alison Byerly also notes:

The old question of whether a falling tree in the forest makes a sound if no one is there to hear it encapsulates the paradox: a tree standing in the forest is not part of the ‘wilderness’ unless a civilized observer is there to see it.20

From the start, forests have been inscribed in cultural economies that – as Byerly’s empiricist reference suggests – are both structural and empirical. One may even argue that our relation to trees and forests is necessarily cultural insofar as it is always a felt, embodied relation. Modernity took that entanglement to its limits in the way it turned forests into a shared ‘memory site’21 in which modern men and women would experience themselves as cultural/sentient beings even as they experimented with new forms of rationalisation.

The rationalisation of modern man’s relation to the forest took the form of management and improvement. As Robert Pogue Harrison insists, the state or the landlord assumed then ‘the role of Descartes’ thinking subject’.22 In Goethe’s Elective Affinities, for instance, the book’s motif of experimentation extends to the world of trees and Edward’s management of his estate is utilitarian before it is Romantic. The ‘improvement’ of his estate’s park tightly harnesses the picturesque aestheticisation of nature to another form of improvement depending on the rationalisation of agriculture. As Charlotte expresses her concern that the planned improvement may prove too costly, Edward retorts with economic arguments spelling the end of an outdated rural community and ensuring better returns:

We have only to dispose of that farm in the forest which is so pleasantly situated, and which brings in so little in the way of rent: the sum which will be set free will more than cover what we shall require, and thus, having gained an invaluable walk, we shall receive the interest of well-expended capital in substantial enjoyment.23

The process of aesthetic autonomisation characteristic of modernity is well under way. Pastoral mimicry warrants agricultural rationalisation. Sense and sensibility collude in the same phrase regime that precisely subjugates the enjoyment of improved nature to an overarching utilitarian world view. Yet, as Goethe’s advertisement also insists from the start, nature cannot be rationalised or aestheticised away:

everywhere there is but one Nature, and even the realm of clear, rational freedom is run through with the traces of a disturbing and passionate Necessity, traces not to be erased unless by a higher hand, and perhaps not in this life.24

Nature resists, and any attempt at instrumentalising it cannot suppress its capacity to unhinge Enlightened reason and even undo the accepted binarism opposing reason and sensation.

Even more central to our argument is the way such sublation speaks of man’s ‘attitude’ and his capacity to articulate and experience his sense of historical belonging. From Austen to Hardy and even Ford Madox Ford in Parade’s End, from Gainsborough to Richard Long, the English imagination is structured around that complex and often unacknowledged negotiation between instrumental reason and historicised sensibility. Austen’s England is indeed, as Jonathan Bate suggests, ‘one in which social relations and the aesthetic sense [. . .] are a function of environmental belonging’.25 As the running metaphor of improvement also shows, from Sense and Sensibility to Mansfield Park, Austen’s England is one in which reason and emotion co-exist and even collude in the definition of the modern self as rational/sentient, or as a fully phenomenological subject, self-reflexively thinking/feeling in the world.26

Gainsborough’s Mr and Mrs Andrews (1750) is also exemplary of such phenomenological negotiation. As the fierce art historical debates surrounding it have shown, its seemingly irenic natural setting is also an embattled ideological ground. Kenneth Clark’s passing remark on Gainsborough’s painting in his 1949 Landscape into Art27 came under considerable flack from cultural theorists, geographers and eco-historians, from John Berger to Gillian Rose.28 Clark’s Rousseauistic reading of the work and the more recent culturalist and Marxist interpretations occupy two symmetrical positions representative of two antagonistic conceptions of modern subjecthood. In Clark’s humanistic apprehension of Gainsborough’s oil, modern subjectivity does not simply express itself through aesthetic contemplation. It invents itself as aesthetic contemplation.29 Meanwhile, the phenomenological alchemy that turns landscape into art abstracts subjectivity. It lifts the subject above the economic and ideological apparatus of instrumental reason. The process of autonomisation at work here is well known and one could read Gainsborough’s entire work as gradually intensifying that process of autonomisation, from the still relatively grounded vision of Mrs and Mrs Andrews or The Gravenor Family (1754) to the famed Mr and Mrs William Hallett (‘The Morning Walk’) (1785) or Mrs Richard Brinsley Sheridan (1785–7). Agonistic readings, such as Berger’s or Rose’s, denaturalise Gainsborough’s aestheticised nature and its repressed economic realities. Aesthetic autonomisation is thus perceived as a strategy of containment that suppresses the underlying system of production.

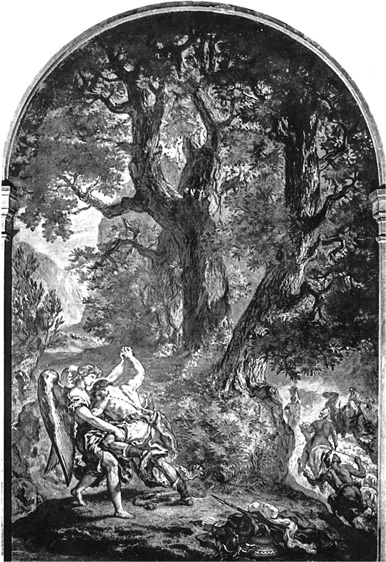

I would like to argue for an even more dialectical approach to such layered images. Gainsborough’s sylvan subjects are not so much conflicted as simply complex. The modern phenomenology in the making here is both rational and sentient,30 both utilitarian and aesthetic, both modern and nostalgic. Recent studies in Gainsborough’s rustic genre scenes, such as Landscape with Woodcutter and Milkmaid (1755) (see Figure 3.1), or his other works in which pollards also feature, tend to show that such antagonistic interpretations fail to do justice to his layered imagination.

Figure 3.2 Thomas Gainsborough, Landscape with Woodcutter and Milkmaid, 1755, oil on canvas, 106 cm x 128 cm, © His Grace the Duke of Bedford and the Trustees of the Bedford Estates. From the Woburn Abbey Collection

The scene in Landscape with Woodcutter and Milkmaid is intensely modern, in the full historical meaning of the term. As Elise Lawton Smith has recently shown,31 it tells us of the current mutations of the rural world, the pollard trees standing for the waning economy of the commons. But the picture functions in other ways, as an allegory of course, warning the spectator against the dangers of idleness, Gainsborough harnessing the ancient idiom of allegory to the language of the modern work ethics. In the same landscape and the same sylvan vision, two cultures, two spatial economies, two models of selfhood come to cohabit.

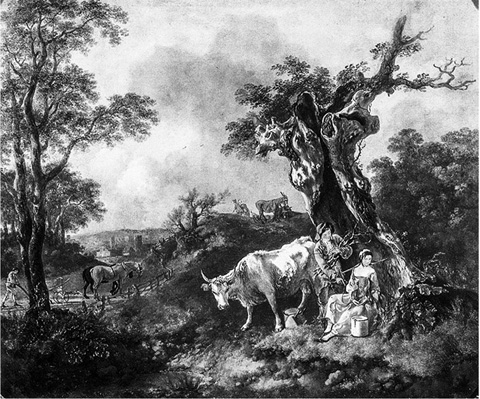

Pollards and timber are the symbols not so much of a changing world vision, but of the complexity of the modern. In Pride and Prejudice, the woods of Rosings in which Elizabeth Bennet learns to read Darcy and herself, as she rereads his letter, are a site of introspection in which the modern subject comes to experience herself as thinking and sentient, as fully phenomenological. But these woods are also the product of instrumental reason, that same reason that invented forestry and enclosed the commons. Similarly, Rousseau’s cherished trees of Ermenonville are both fountains of emotion and potentially the liberty trees of the French Revolution (see Figure 3.1).32

Figure 3.3 Arbres de la Liberté, print, Paris, Musée Carnavalet, © Musée Carnavalet/Roger-Viollet

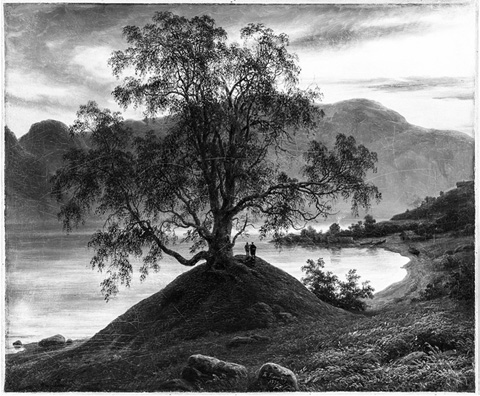

The sylvan imagination of modern Europe is thus far more entangled than our obsession with ruptures and historical periodisation may imply. The anthropomorphic and pantheistic imagination of the likes of Charlotte Brontë in Jane Eyre, Wordsworth, Caspar David Friedrich, or Thomas Fearnley (see Figure 3.1) should not be read as merely antagonistic to changes in sensibility and economic conditions. Jane Eyre’s chestnut tree crystallises a sign system in which dominant, emergent and residual cultures – to resort to Raymond Williams’s taxonomy in ‘Base and Superstructure in Marxist Cultural Theory’33 – do not so much cohabit as function as one and fashion a subjectivity that sustains itself through a constant negotiation between seemingly contradictory aspirations and mind logics.

Figure 3.4 Thomas Fearnley, Slindebirken, 1839, oil on canvas, The National Museum of Art, Architecture and Design, Oslo

The phenomenological subject of modernity experiences herself as a sentient being through a contemplation whose empirical basis is also that of rational experimentation. This is the rational/sentient subjectivity that Joseph Wright of Derby captures in his 1768 An Experiment on a Bird in the Air Pump. Nature is subjugated in order for the subject of Enlightenment to come into his own. The same sublime nature that fuels Friedrich’s or Fearnley’s restless and wandering desire presses at the window of Wright of Derby’s experimentation room and is kept at bay, as if foreclosed. A similar chiaroscuro technique is used by all three painters as an index of transcendance and also as a meta-pictorial instrument through which they experiment with vision and technique, thus anticipating later modernist experimentations.

The modern subject of epistemological reason is also the modern subject of phenomenology, grounded in empirical observation, looking both above and ahead, and yet also rooted in the here and now of her or his presence to the world of the senses and emotion. Acknowledging modern subjectivity as layered rather than conflicted implies we rethink modernity’s relation to its own historicity, a historicity we have too often been taught to think of as agonistic and self-divided. To return to Foucault’s argument, modernity might thus be approached as a self-reflexive practice enacting a sublation of binary tensions.

Jumping two centuries, I would like to try and see how contemporary art has reappropriated such critical historicity for a deconstruction of the suppressed narrative of modernity. Hamish Fulton’s sylvan wanderings may provide ample material for such explorations, but I would like to turn to an installation by Anya Gallaccio – Beat (2002) – that forced the spectator to a violent experience of her or his own modernity by questioning the economy of aesthetic experience as engineered by the museum. Beat was commissioned by Tate Britain to coincide with Gainsborough’s great exhibition also held at Tate Britain from October 2002 to January 2003. For Beat, Gallaccio took inspiration from the Tate Britain collections and ‘began to consider the possibilities of working with that archetypal symbol of the British landscape: the oak tree’.34 She ‘fill[ed] the South Duveen galleries with whole tree trunks, with their bark intact but with their branches removed’, thus ensuring ‘their original and “natural” state is not forgotten’.35

As she has done previously, for instance in Glaschu, her 1999 in-situ work at Lanarkshire House, now the Corinthian, in Glasgow, Gallaccio uses site to reflect on the way it functions as a memory site. In the two installations, she more specifically produces embodied allegories of the English/British layered relation to nature. Nature’s uncanny intrusion into the exhibition space does not merely transcend the nature/culture dichotomy; it discloses the overlooked, repressed memory of late modernity. Gallaccio’s response to the two commissions is a political response that confronts modernity’s ramified identity. In both cases, she engages with the artistic or visual language associated with the site’s symbolical functions: a national museum in the case of Tate Britain, and not any museum, the museum solely devoted to the grand narrative of British art; a listed building, in the case of Lanarkshire House, formerly Glasgow’s Sheriff Court and Justice of Peace Court, and which when extended by John Burnet in 1876–9, built on an earlier neo-classical building.

In Glaschu (Glasgow in Scottish Gaelic), Gallaccio chooses to reproduce a carpet design she had found in the archive of a local factory. Cracks created in the concrete floor of the neo-classical house allow foliage to grow through, producing the impression that nature may gradually invade that cultural site and reappropriate it.

In Beat, she enters in a dialogue with Gainsborough’s conflicted vision of nature. Her agonistic installation taps into the hidden history of the building and also into the ideological subtext of much of Gainsborough’s work and of the English cult of nature. Needless to say, the oak trees of the installation are powerful quotations of the landscape tradition of English painting. They are paradoxical, embodied abstractions of a grand narrative that itself is haunted by the memory of the lost forests of England. Not only is the oak tree, to use curator Mary Horlock’s phrase, ‘a powerful signifier of the British countryside’;36 here it is meant to function as a ‘quasi-object’, that is, one of those hybrids, neither fully natural nor exclusively cultural, which, Bruno Latour argues in We Have Never Been Modern, is the hallmark of our current sense of political and epistemological crisis.37

The objective reality of the installation is itself hard to circumscribe as it encompasses the site itself. The location is of course part of Beat’s meaning. Tate Britain’s Duveen Galleries did not merely house Gallaccio’s work. They were fully part of the work’s quasi-object mechanism and were in their turn revealed as another sign system in which the museum, as imagined and funded by one of the icons of Victorian industrialism – the sugar magnate, Henry Tate – engineers a form of a-historical contemplation suppressing the museum’s political rationale. That memory is present in the title of the installation, Beat, an ironical reference to the beetroots used in the production of white sugar. It is also embodied in another component of the installation: two slabs of molten sugar placed in the North Duveen.

As the third part of the installation makes clear – a hollowed root filled with water whose calm surface reflects the gallery space – Beat is intensely reflexive. Its ethical reflexiveness extends of course to the grand narrative developed by the museum and its complex dramatisation of the visitor’s sense of cultural belonging; down to its most specific detail: the oak trees Gallaccio worked with originated from the Englefield Forestry Estate in Berkshire, a ‘traditionally managed rural estate’38 in its time painted by John Constable.

Beat’s ethical reflexiveness is no intellectual play. It is embodied in the physical experience of the visitors who encounter the dead oaks as they enter the museum space. Gallaccio’s installation functions as a phenomenological conceit. It develops a sustained allegory signifying the discursiveness of the museum experience through sensation. Confronted with the dead oaks, we can no longer ignore the fact that the museum is grave-like in more than one way. Its celebration of the art of the past cannot be abstracted from a sense of ‘our historical being’ nestling in the dominant cultural apparatus, a sense that the museum conceals and represses.

Confronted with the dead oaks, the visitor is both necessarily shaken out of her or his complacency and forced to reflect. She or he may choose not to reflect and head straight to the galleries housing the permanent collections. But even that movement of denial is trumped by the overall reflexiveness of the work. Beat’s site-specificity turns space into a site of embodied intellection. Gallaccio’s experimentation with space – a characteristic inherent to the very genre of installation art – offers a form of experiential criticity, in which aesthetic experience is newly endowed with a profound and disturbing historicity. Entering the museum we are forced to confront our own historicity, our own existence not only in the here and now of aesthetic contemplation but also as it survives through a long, conflicted history of denial.

Beat is thus both mausoleum and ghost chamber. As a quasi-object, it compels us to an embodied moment of reflexiveness. At the heart of the museum machinery, it harnesses sensation to a critical task that is both physical and intellectual. With it, modernity’s sylvan imagination is meant to be understood for what it has always been: a contested and layered site, a site in which rationality and experience are interdependent. Its ethos remains intensely modern. Its criticity springs from the heart of modernity’s embodied consciousness. The agonistic dialogue it initiates with our empirical memory is one in which our modernity does more than survive its own melancholy failure. That dialogue is one in which body and reason become fully productive of a historical reflexiveness that is both concept and practice.

NOTES

1.In the field of visual arts, such untimeliness might also be characteristic of the temporal turn of contemporary art; see Christine Ross, The Past Is the Present; It’s the Future Too, London: Continuum, 2012.

2.Enrique Dussel, ‘Eurocentrism and Modernity’, boundary 2, The Postmodernism Debate in Latin America, 20: 3 (Autumn 1993), 65–76, 65. He is referring here to Jürgen Habermas’s The Philosophical Discourse of Modernity (1985), Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 1987 and to Charles Taylor’s Sources of the Self: The Making of the Modern Identity, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1989.

3.See Terry Eagleton, Heathcliff and the Great Hunger: Studies in Irish Culture, London: Verso, 1995.

4.Sanjay Subrahmanyam, Three Ways to Be Alien: Travails and Encounters in the Early Modern World, Waltham, MA: Brandeis University Press, 2011.

5.On the subject, see a recent essay by French philosopher Jacob Rogozinski, Ils m’ont haï sans raison. De la chasse aux sorcières à la Terreur, Paris: Cerf, 2015.

6.Sanford Budick and Wolfgang Iser (eds), Languages of the Unsayable: The Play of Negativity in Literature and Literary Theory, Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1987.

7.Jean-François Lyotard, Le Différend, Paris: Éditions de Minuit, 1983.

8.Michel Foucault, ‘What Is Enlightenment?’, in The Foucault Reader, ed. Paul Rabinow, New York: Pantheon Books, 1984, pp. 32–50, p. 39.

9.Ibid. p. 42.

10.Michel Foucault, ‘Qu’est-ce que les Lumières?’, in Daniel Defert and François Ewald (eds), Dits et écrits, 1976–1988, Paris: Gallimard, coll. Quarto, 2001, pp. 1381–97, p. 1390.

11.Foucault, ‘What Is Enlightenment?’, p. 45.

12.Ibid. p. 45.

13.F. Scott Fitzgerald, The Great Gatsby (1926), Harmondsworth: Penguin Modern Classics, 1986, p. 171.

14.Ibid. p. 171.

15.Ibid. p. 171.

16.Simon Schama, Landscape and Memory, London: Vintage, 1995, p. 153.

17.See W. G. Hoskins, The Making of the English Landscape (1955), Toller Fratrum: Little Toller Books, 2013, pp. 84–90. For a synthesis of the research on the topic, see for instance Ian D. Rotherham (ed.), Trees, Forested Landscapes and Grazing Animals: A European Perspective on Woodlands and Grazed Treescapes, London: Routledge, 2013; John Sheail, ‘The New National Forest, from Idea to Achievement’, The Town Planning Review, 68: 3 (1997), 305–23. On eco-history, see Jean-Paul Deléage and Daniel Hémery’s very early essay ‘De l’éco-histoire à l’écologie-monde’, L’homme et la société, 91: 2 (1989), 13–30.

18.See Jonathan Bate, The Song of the Earth, ebook, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2002, ch. 1.

19.Robert Pogue Harrison, Forests: The Shadow of Civilization, ebook, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1992, ch. 3.

20.Alison Byerly, ‘The Uses of Landscape: The Picturesque Aesthetic and the National Park System’, in Cheryll Glotfelty and Harold Fromm (eds), The Ecocriticism Reader: Landmarks in Literary Ecology, Athens, GA: The University of Georgia Press, 1996, pp. 52–68, p. 58.

21.I am of course adapting Pierre Nora’s meta-category: Pierre Nora (ed.), Les lieux de mémoire, Paris: Gallimard, 1984–92. In section 3 (‘Les France’) of volume 2 of this collective work, a chapter is devoted to the forest: Andrée Corvol, ‘La forêt’, in Les lieux de mémoire, Paris: Gallimard, coll. Quarto, 1997, pp. 2765–816.

22.Harrison, Forests, ch. 3.

23.J. W. Goethe, Elective Affinities, ebook, Boston: D. W. Niles, 1872, ch. 7.

24.Quoted in N. K. Leacock, ‘Character, Silence, and the Novel: Walter Benjamin on Goethe’s Elective Affinities’, Narrative, 10: 3 (2002), 277–306, p. 285. See also Walter Benjamin’s essay ‘Goethe’s Elective Affinities’, in Marcus Bullock and Michael W. Jennings (eds), Walter Benjamin: Selected Writings. Volume 1, 1913–1926, Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1996, pp. 297–359, p. 315.

25.Bate, The Song of the Earth, ch. 1.

26.On the complex relation between nature, naturalism and Enlightenment, see Taylor, Sources of the Self, pp. 328–30.

27.Kenneth Clark, Landscape into Art, London: John Murray, 1949, p. 34.

28.John Berger, Ways of Seeing, London: Open University, 1972, p. 107; Gillian Rose, Feminism and Geography: The Limits of Geographical Knowledge, London: Polity Press, 1993. See especially ch. 5, ‘Looking at Landscape: The Uneasy Pleasures of Power’, pp. 86–112.

29.On this process of aesthetic grounding, see once more Benjamin, ‘Goethe’s Elective Affinities’, p. 315.

30.For a reading of the correlation to be established between Gainsborough’s painterly vision and empiricism, see Amal Asfour and Paul Williamson, ‘Splendid Impositions: Gainsborough, Berkeley, Hume’, Eighteenth-Century Studies, 31: 4 (1998), 403–32.

31.Elise Lawton Smith, ‘“The Aged Pollard’s Shade”: Gainsborough’s Landscape with Woodcutter and Milkmaid’, Eighteenth-Century Studies, 41: 1 (2007), 17–39.

32.See Schama, Landscape and Memory, ch. 3.

33.Raymond Williams, ‘Base and Superstructure in Marxist Cultural Theory’, New Left Review, 1: 82 (November–December 1973); reprinted in Raymond Williams, Culture and Materialism, London: Verso, 1980, pp. 31–49.

34.‘Anya Gallaccio, 16 September 2002–16 January 2003’, available at <http://www.tate.org.uk/whats-on/tate-britain/exhibition/anya-gallaccio> (last accessed 13 December 2016).

35.Ibid.

36.Mary Horlock, ‘The Story so Far’, in Anya Gallaccio: Beat, London: Tate Publishing, 2002, pp. 11–17, p. 12.

37.Bruno Latour, Nous n’avons jamais été modernes, Paris: La Découverte, 1991. The term is itself borrowed from Michel Serres’s Le parasite, Paris: Grasset, 1980. A similar concept is used by David Matless in the introduction to his important book, Landscape and Englishness, ebook, London: Reaktion Books, 1998: ‘The power of landscape resides in it being simultaneously a site of economic, social, political and aesthetic value, with each aspect being of equal importance’.

38.Horlock, ‘The Story so Far’, p. 12.