On First Looking into

Derrida’s Glas

J. Hillis Miller

Then felt I like some watcher of the skies

When a new planet swims into his ken;

Or like stout Cortez when with eagle eyes

He star’d at the Pacific – and all his men

Look’d at each other with a wild surmise –

Silent, upon a peak in Darien.

John Keats, ‘On First Looking into Chapman’s Homer’1

My current work is on the question of what actually happens when someone (you or I, dear reader) opens up a book or a journal and starts reading a novel, a poem, a short story, a critical essay, a critical book or a philosophical work. My claim is that what happens is extremely strange. Moreover, it differs from person to person and for a given person from one time to another. What happens in reading can by no means be limited to just making rational sense of the words, as pedagogues and reading specialists sometimes claim should be the primary goal of reading. Cognitive science and brain scans are of little use in this project, since they can tell me which parts of my brain light up when I read a given text, but do not generally pay attention to my report of my subjective experience. ‘It’s not scientific.’ A report of my subjective experience in a given case, however, untrustworthy as it may be, is the only evidence in support of carrying out my quixotic project.

I have already written essays working on this project about passages in an illustrated novel by Anthony Trollope (Framley Parsonage), a poem by Yeats (‘The Cold Heaven’), a poem by Wallace Stevens (‘The Motive for Metaphor’) and a passage in a book by Derrida (Otobiographies).2 In this present essay, here and now, I shall try to identify from memory as best I can what happened in my mind and feelings when in 1974 I first picked up Derrida’s Glas3 in Bethany, Connecticut, and read. Tolle, lege! Doing that certainly produced ‘wild surmise’.

Or, rather, I shall perforce compare what happened then (a first reading) with what happens here and now, in Deer Isle, Maine, from 13 October to 2 November 2015, in a much later reading. The latter unavoidably stands as a screen between now and then. I now have long since read the whole of Glas, carefully, word by word. All during the fall of 1974 and beyond I read a few pages early each morning while doing my running in place. I read it, of course, necessarily in the original French, since no translation as yet existed. My French was pretty good, and I had read earlier work by Derrida in French, but I quickly discovered that to read Glas requires more than understanding sentences like ‘Je vais au tableau noir’ or ‘Je prends ma place’. Not that such an elementary level of French was good enough for Derrida’s De la grammatologie either!4 I started out with Glas trying to read just the Hegel column on the left, planning to come back later to the Genet column. I soon found, however, that Derrida’s layout was too much for me. My eye kept drifting to the right towards the Genet column. So I gave in and read both columns of a given page at the same time, with binocular vision, looking for resonances and, usually, not finding any, but having my intellectual and affective confusion exacerbated.

My reading the first page of Glas now is quite different, partly because it is a second reading and has, for starters, as a presupposition all that I remember of my first reading, especially my conviction that it is a truly amazing book, a masterwork of postmodernism. I now have at hand, moreover, all the help in reading Glas that was not available then. That includes especially the English translation by John P. Leavey, Jr. and Richard Rand,5 as well as the big book of commentary and annotation, Glassary, by Gregory L. Ulmer and John P. Leavey, Jr., with a valuable ‘Foreword’ by Derrida himself.6 In 1974, by contrast, I was pretty much on my own, even though I had read carefully most of Derrida’s previously published work and had heard his seminars at Johns Hopkins and (I think) already the first annual ones at Yale.

The printing of Glas was completed on 27 September 1974, according to the legal notice at the end of the book. On a day in late September or early October of that year, I think it must have been, I went out in all innocence from my house at 28 Sperry Road in Bethany, Connecticut, to get my daily mail from our rural roadside mailbox. I had moved from Johns Hopkins to Yale in 1972. There among the bills and ads was a sizable package from France. I carried it inside and opened it. Behold! It was a book about the size of a small telephone book with Glas in big letters on the cover and the name Jacques Derrida in small print plus the name of the publisher, Éditions Galilée, in slightly larger print. Here is a scan of what remains of that cover, in somewhat battered condition and separated from the book itself by all those months of reading the book (Figure 3.1). At some point over the years I tried unsuccessfully to glue it back onto the rest of the book.

Galilée! Of course. That is French for the astronomer and mathematician Galileo (1564–1642). It could also refer to the region of Israel called Galilee. I don’t know which, or both, the founding editors of Galilée had in mind. Joanna Delorme, who runs Galilée’s permissions department now, would probably know, but the allusion to Galileo, deliberate or not, would in any case remain. Galileo was famous, among other things, for discovering the satellites around Jupiter and for observing the planet Neptune. The lines quoted from Keats in my epigraph, ‘Then felt I like some watcher of the skies / When a new planet swims into his ken’, apply especially well to Galileo.7

If the publisher of Glas is named for that watcher of the skies who observed a new planet, then the book is published under that aegis. Its name commits it to new discoveries. My experience on first opening Glas was certainly like discovering a new planet. I had never seen anything like it. So to my mental image by way of a fortuitous association of stout Cortez ‘discovering’ the Pacific must be added the imaginary scene of Galileo looking through a telescope at a new planet. Derrida once mentioned to me soon after Glas was published that doing so had nearly bankrupted Galilée, so costly was it in those pre-computer days to get the typefaces and the arrangement of the words on the pages right. Derrida said, with a gesture of his outstretched hand, palm down about three feet from the floor, that the proofs were ‘This high.’ That mental image from my memory bank must be added to all the others Glas generates in my mind. Galilée, finally, is another of the words in ‘gl’, or almost in ‘gl’, that are so important in Glas. They are glottal stop words that mimic strangulation when they are uttered.

The word ‘galactics’ (galactique) (another ‘gl’ word) is used in the inserted ‘Blurb’ (of which more later) to name the arrangement of the elements of the right, or Genet, column. ‘Galactics’ is opposed to the ‘dialectics’ of the left, or Hegel, column and may allude obscurely to Derrida’s publisher: ‘Une dialectique d’un côté, une galactique de l’autre.’ Galilée went on to publish many books by Derrida and now owns the rights to his unpublished ‘remains’, so they have got their investment back and then some, but they have served him well.

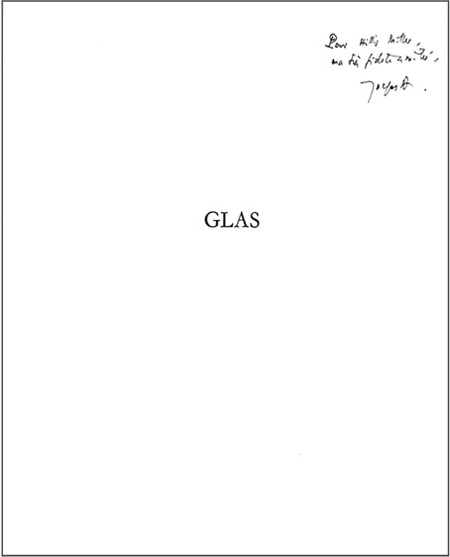

When I opened the book, I found the title page had a handwritten dedication to me by Derrida (Figure 3.1). He already had the touching generosity of sending me inscribed copies of his books as they came out. I have a lot of them from over the years until his death. They have monetary as well as much sentimental value. I used to tell him that I would support myself and my wife in our old age by selling my inscribed Derridas one by one. I have not had to do that yet.

Figure 11.2

In addition, the book had a separate insert of a smaller page size, the sort of self-explanation, aids to reading, by the author that often is printed on the back cover of a book but in France was commonly printed on a loose sheet. Derrida used one form or another of these pre-orientations habitually. Since the ‘Blurb’ provides invaluable directions for how to read Glas, here are scans of both recto and verso of my yellowed and torn copy, with the corner torn off in some accident over the years (Figures 11.3 and 11.4).8

Figure 11.3

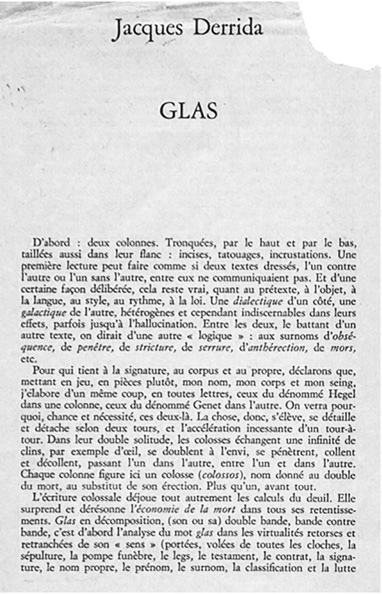

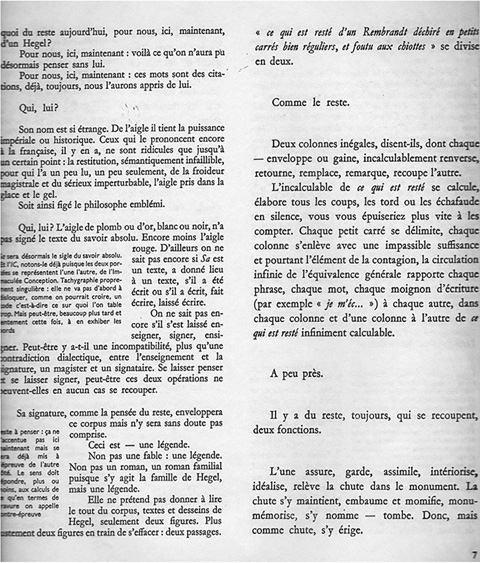

With all that preliminary digitation and deciphering as context, I must finally have opened Glas to the first page. It is numbered 7 in the book, though it is actually the first page of the text proper. I will call it in this essay ‘the first page’ or ‘page one’. Here it is, again scanned from my original battered copy (Figure 3.1).

I give all these details in part to remind my readers that beginning to read a book has all sorts of physical contexts that involve hands, fingers and other parts of the body as well as looking at the words on the page. As many other people have argued, this means that reading a printed book is quite different from reading an e-text version of the same text.

*

When I began to try to read the first page of Glas I was certainly like stout Cortez (actually stout Balboa, Keats’s mistake) discovering the Pacific Ocean, ‘silent, upon a peak in Darien’. I had great difficulty even beginning to understand what was going on. Remember that I had no translation and no commentary beyond that ‘Blurb’ to help me. I knew Derrida’s previous work quite well, but nothing in that work except ‘Tympan’, the prefatory essay to Marges, published in 1972, two years before Glas, at all prepared me for the typographical high jinks of Glas.9 Though I read French quite well, as I have said, that first page was full of words I did not know. This included the word Glas itself, which means, my Petit Robert10 tells me, a trumpet call as well as the tolling of a church bell for a funeral and, figuratively, the end of a hope (for example, ‘That rang the knell on my hope to make it to Maine that summer’). The word glas comes from medieval Latin classum, ‘class’, and classicum, ‘sonnerie de trompette’, so it involves classification as well as the tolling of a church bell and a trumpet call, as Derrida himself signals. His list of meanings – what he calls in the ‘Blurb’ ‘les virtualités retorses et retranchées de son “sens”’ (‘Blurb’, recto) (‘the twisted and cut out virtualities of its “sense”’ (Glassary, 28)) – of the word glas is outrageously long. I give the English translation:

staffs, peals of all the bells, the burial place, the funeral pomp, the legacy, the contract, signature, proper name, forename, surname, classification and the class struggle, the work of mourning in its production relations, fetishism, transvestism, the ‘toilette’ of the deceased, incorporation, introjection of the corpse, idealization, sublimation, relief, vomit, the remain(s), etc. (Glassary, 28)

‘Etc.’?! Come on, Jacques, surely the word cannot mean all those diverse things! So much for dictionary meanings. But yes (Mais oui), for Derrida, ‘virtualities of its sense’ covers all those things and more (‘etc.’).

It is easy to see, once you have read the whole book, that Derrida’s list of virtual meanings for the word glas covers all the salient themes of Glas. The volume must be seen as an untangling and elaborate commentary on all those virtual senses of the word. A word means for Derrida all its possible uses and these are typically, for him, limitless, ‘infinitely calculable’, as the right column of the first page says explicitly about the word reste. This infinite calculability means, among other things, that anything like an even modestly comprehensive commentary on Glas, line by line and page by page, would be of enormous length. When I get around later on in this essay to saying something about the meaning of the first page of Glas, I shall, perforce, limit myself to a few incomplete remarks about one key word in Glas, in this case reste, remain(s), as a noun and as a verb. Otherwise, my essay would be interminable.

*

One of Derrida’s targets in Glas is the assumption that a word has a definite set of meanings that can be given in a dictionary and that allows for a verifiable identification of page one’s meaning. This would be one form of ‘absolute knowledge’, in Hegel’s phrase, given on page one by Derrida as sa, for savoir absolu. This is the meaning that scholars and students are supposed to identify and specify. Derrida asks what follows from that dismantling of absolute knowledge in a complex question in the ‘Blurb’:

What remains of absolute knowledge? of history, philosophy, political economics, psychoanalysis, semiotics, linguistics, poetics? of work, language, tongue [mostly in the sense used in a phrase like ‘foreign tongue’ – JHM.], sexuality, family, religion, State, etc.? (Glassary, 28)

The implied answer is that nothing remains except fragments, morsels, that cannot be reassembled into the kind of ‘absolute knowledge’ Hegel promised could be attained. The multiple meanings of such a word as glas ‘deconstructs’, if I may dare to use that word, all those disciplines. Make no mistake: Derrida’s target through all the fascinating exuberance of Glas is the whole edifice of Western intellectual assumptions.

One of Derrida’s most powerful tools for dismantling that edifice is those lists of apparently heterogeneous entities that are said somehow to be the same, to be validly put in apposition. Here are two examples from the foot of the right-hand column of Glas, page one. Derrida is talking about the first of two functions of ‘the remain(s)’:

The first [function] assures, guards, assimilates, interiorizes, idealizes, relieves [in the contradictory sense, in part, of the final stage of the three stages of the Hegelian dialectic. That stage is reached by an act of aufheben, meaning abolish and preserve, sublate, cancel and lift up.11 Relève is the common French translation of the German word aufheben – JHM.] the fall [chute] into the monument. There the fall maintains, embalms, and mummifies itself, monumemorizes and names itself – falls (to the tomb(stone)) [tombe]. (E1/G7)

Wow! Are the words in these lists synonyms or do they make some kind of progression? It is not possible to be sure.

I met up on that first page with other words the meaning of which I did not know, like seing (signature), as well as words whose meaning I more or less knew, like reste (remainder, remains), but that are used in Glas in odd ways, in strange syntactical combinations or in a series of different senses. That exemplifies Saussure’s claim that the meaning of a word depends on the sentence in which it is used.

*

Paul de Man, in a notable passage in ‘Conclusions: Walter Benjamin’s “The Task of the Translator”’, distinguishes, with some help from Walter Benjamin, between ‘Hermeneutics’ and ‘Poetics’, das Gemeinte and die Art des Meinens, what is meant and the way that meaning is said.12 De Man argues that these two ways of reading interfere with one another, or may be incompatible, or impossible to do at the same time. That first page of Glas and all the rest (remainder!) of the book tend to place poetics over hermeneutics. This happens by way of such things as typeface, the placement of assemblies of words on the page, the constant use of ellipses, sentence fragments, and the interference of outrageous wordplay over clear paraphrasable meaning: puns, alliteration, polysemantics, polyglottism, assonance, consonance, lists of not quite synonymous words or phrases, such as all those words beginning in gl, etc. It was then and is now my habit and training to seek out what is meant, das Gemeinte. In Glas, die Art des Meinens keeps me to an amazing degree from getting on with das Gemeinte.

One could define all this wordplay in either or both of two ways: either as a magnificent exploitation of the richness of the French language or as a revengeful deconstruction, once and for all, of the vaunted clarity of French. If the latter, this is because the rich multiple meanings of words in French (as in English or other languages, too) make it impossible to mean one thing without at the same time inadvertently meaning a lot of other things. So much for any clear statement of savoir absolu! The French language (tongue) was imposed on the child Derrida as an Algerian Jew, victim of French colonial imperialism. That imperialism is alluded to in the passages about Hegel (aigle [eagle] as pronounced by the French) in the left column of Glas page one: ‘His name is so strange. From the eagle it draws imperial or historic power. Those who still pronounce his name like the French (there are some) are ludicrous only up to a certain point’ (E1/G7).

The French language will never be the same again after Glas, just as the English language will never be the same again after Joyce’s Finnegans Wake. Derrida read the Wake carefully during his year on an école normale fellowship at Harvard during the 1950s. Finnegans Wake was undoubtedly one of his models for Glas. Joyce too, like Derrida, was a victim of colonialism and was forced to use the tongue of the conqueror, just as I am in a different way. We Americans went on using English and basing our ethos on British literature long after we won the War of Independence, right down to the present. We still are taught that all Americans should read Shakespeare. Why? My ancestors were chiefly German immigrants. Why would not Goethe or even Hegel do as well for me as Shakespeare? Hegel, by no means French, was after all the basis of French university intellectual life in Derrida’s youth, in Sartre’s time. Derrida was on official record as at work writing a habilitation dissertation on Hegel, of which Glas is a sardonic, belated and defiant fulfilment.

*

Two things happened at once and happen again now when I try to ‘read’ that first page of Glas: (1) I made, and now make again, a heroic and on the whole unsuccessful attempt to figure out just what Derrida is saying, just what the words mean. I shall return to this effort at the end of this essay. (2) A strange inner space opened up then and opens up again within me. That imaginary space is generated partly by the arrangement of the words on the page and partly by what that ‘Blurb’ says, as well as by what the text itself says. This space is made up of two tall columns side by side in a sandy desert and encrusted with inscriptions that interact in complex ways. These columns are also colossi, that is, like enormous memorial statues of kings and the like. The words on the page are, after all, in parallel columns that are covered with inscriptions of various sorts, with strange inserts on the sides in smaller typeface, as you can see from my scan above of page one (Figure 3.1). Derrida gives these inserts striking names drawn from windows in walls: ‘Judases’ and ‘Jalousies’. A Judas window is an aperture enabling a prison guard to see into a cell without being seen by the prisoner, a peephole. The allusion is to the way Judas betrayed his pretended friendship for Jesus.13 Jalousies is the French word for what in English we call louvred windows.14

I have found that what actually happens when I read a poem, a novel, a philosophical text or a critical text is the spontaneous generation of a quite definite imaginary space with appropriate feelings as well as a visual vividness not entirely justified by the words on the page. Glas is no exception. There before my mind’s eye are those two inscribed columns standing side by side in a desert solitude. They are a scary and forbidding sight. This imaginary vision reminds me of those ‘two vast and trunkless legs of stone’ standing in the desert in Shelley’s sonnet ‘Ozymandias’.15 This is an example of those irrelevant and fortuitous associations that are one of the (perhaps distressing) things that happen, to me at least, in reading. Can I be the only person for whom this occurs? I doubt it.

*

The generation of an imaginary image of two vast columns in the desert is perhaps primarily brought about by the way the words are arranged on the pages of Glas, but three actual passages near the beginning powerfully endorse that mental and affective image. I give a citation from each in the order in which I encountered them, first a passage in the inserted ‘Blurb’, then a passage on the first page of Glas, then one of the two passages from Hegel that are given on the following pages. For the convenience of the reader I give these ‘passages’, somewhat reluctantly, in the English translations, with some of the French interpolated. The French versions of the first two are in any case given in my scans above.

Derrida, by the way, plays on the innocent-looking word ‘passage’. He makes it mean a movement towards disappearance, as we speak of someone’s death as a ‘passing’. He speaks at the bottom of the left-hand column of Glas on page one of the two passages from Hegel on which he will focus as ‘two figures in the act of effacing themselves, two passages’ (E1/G7).

The first ‘passage’, caught in the act of effacing itself, I would have read uncomprehendingly, en passage to Glas itself, since I did not yet know just what he meant by ‘two columns’. This is the first paragraph of the ‘Blurb’, in the English translation in Glassary, with some key words in French interpolated. I also insert some commentary in brackets along the way. I do this for brevity’s sake, rather than appending my commentary separately and therefore necessarily at greater length. I have quailed before the idea of putting my commentary in as Judas windows:

First of all [D’abord]: two columns. Truncated at the top and the bottom, also carved [taillées] in their flank: interpolated clauses, tattooings, incrustations. A first reading can act if the two erected [dressés] texts, one against the other or one without the other, do not communicate between themselves. [That was the way I tried at first to read Glas – JHM.] And in a certain, deliberate way, that remains true, concerning pretext, object, language, style, rhythm, law. [He means, I guess, that the two columns seem at first to be separate texts in different styles, one about Hegel, the other about a greatly different writer, Genet. This is still a shocking juxtaposition – JHM.] A dialectics on one side [How can anyone write about Hegel without engaging in dialectical reasoning? – JHM.], a galactics on the other [I suppose that is an allusion to Walter Benjamin’s idea in The Arcades Project16 of gathering together passages that are not sequential but arranged in an imaginary spatial array, like a galaxy or like the stars in a constellation. Or it may be an obscure allusion to Galilée, the name of the publisher of Glas, as discussed above – JHM.], heterogeneous and yet indiscernible [indiscernables: the French word has a somewhat different meaning from the English homonym. The French has the double senses of ‘inseparable’ and ‘impossible to be distinguished or differentiated from one another’ – JHM.] in their effects, at times up to hallucination. [Why is this hallucinatory? I suppose because such a similarity in effects of two such different columnar texts seems crazy, like a hallucination – JHM.] Between the two the clapper [le battant: I should have thought ‘beating’ or ‘vibrating’ might have been a better translation, but my Petit Robert gives the noun and the adjective three additional meanings: the clapper of a bell, the beating of a heart, and the pelting of a heavy rain – JHM.] of another text, one would say of another ‘logic’: with the surnames [surnoms: nicknames] obsequence, pénêtre, strict-ure, lock, antherection, bit [mors], etc. [Here is another of Derrida’s bewildering lists of words. What in the world, for example, is an ‘antherection’ (anthérection)? Erections in various senses appear often in Glas, both in the sense of the erection of a tower and in the sexual sense. Derrida sees all towers, including his two columns, as phallic, but what about the prefix ‘anth-’? It can hardly just mean ‘anti’, in the sense of detumescence, or Derrida would have written ‘anti’. The answer to my question requires reading carefully the whole Genet column of Glas, with its treatment of homosexuality in Genet’s writings. Sartre’s big book on Genet hovers somewhere in the background.17 Genet’s homosexuality is placed in juxtaposition with Hegel’s family life, treated in the left column. What, moreover, is the word for a morsel (mors) doing at the end of the sequence, and what in the world is an ‘obsequence’ (obséquence)? It must have something to do with exaggerated marks of politeness, but what that has to do with the third text beating between the two columns and generated by their interaction beats me. Maybe the two columns are obsequious to one another by figuratively bowing with exaggerated politesse. The defeat of my comprehension makes my heart beat faster. Just where on the page, by the way, is that autre texte to be found? It must be a hallucinatory or ghostly text that exists and does not exist, but is generated virtually by the interaction between the words in the two columns. I certainly had no idea what those words in this list meant and what they were doing there when I first read the ‘Blurb’. One answer to my questions, I suppose, is, ‘Read the whole of Glas, all 291 pages of it, carefully and thoughtfully, word by word and line by line, with one eye on each column, and you will find out.’ Good luck. I’ll see you in a couple of years or maybe more. Let me know when you are ready – JHM.] (Glassary, 28)

*

In any case, the passage about the two columns in the ‘Blurb’ encourages me further to do what I already do spontaneously when I look at page one. I see it in my mind’s eye as a strange spatial scene of two physical inscribed or incised columns standing side by side. A passage on the right column of page one reinforces that mental image but also greatly complicates it or even makes it impossible to imagine it as a coherent visual scene. My earlier essay on a passage in Derrida’s Otobiographies18 similarly discovers that the passage in question also is not imaginable in the way the description of a drawing room in a novel by Anthony Trollope can be successfully imagined to look. This success occurs in Trollope’s case even if that subjective image goes beyond the actual details Trollope gives and imports something from my memories of actual drawing rooms from ‘real life’, or from films and television.

*

Here is my second pillars passage, this time given in the English translation of Glas by Leavey and Rand. It is a pretty bewildering series of notations, in English or in French. Again, I give glosses in parentheses along the way:

Two unequal [Why are they ‘unequal’ (inégales)? Because they are in different typefaces and have a different number of total words, though they fill the same space on the page? – JHM.] columns, they say distyle [disent-ils] [The similarity in sound is the justification for translating a phrase which means ‘they say’ as ‘distyle’. It adds to my mental image of those two columns in that ‘distyle’. ‘Distyle’ means ‘a temple having two columns in front’ – JHM.], each of which envelop(e)(s) or sheath(es) [enveloppe ou gaine: gaine in French has a bewildering number of meanings, including, as a noun, the cover for an umbrella or even (no doubt somewhere in Derrida’s mind) ‘vagina’, which means ‘sheath’ in Latin – JHM.], incalculably reverses, turns inside out [as one might turn the finger of a glove inside out, a figure Derrida elsewhere forcefully uses, under the name of ‘double invagination’.19 The fingers of a glove are already vagina-like sheaths. To push one finger of the glove inside itself makes another vagina-shaped container. Hence ‘double invagination’. You will note that Derrida’s phrase does not necessarily name a static fact but by way of the ‘-ion’ at the end of ‘invagination’ may name an ongoing action. Part of the reason for my failure to imagine the scene Derrida’s words name in this citation is that, unlike my mental image of the drawing room in a Trollope novel, it is in constant dynamic movement like a glove finger constantly turning to outside in and then back to outside out – JHM.], replaces, remarks, overlaps [recoupe] the other. [. . .] each column rises with an impassive self-sufficiency, and yet the element of contagion, the infinite circulation of general equivalence relates each sentence, each stump [moignon: I suppose this is a synonym of the enigmatic mors (morsel) in the insert, but ‘stump’ obscurely implies what remains after an emasculation – JHM.] of writing (for example, ‘je m’éc. . .’) [‘I gag. . .’, later important in Glas, is a play on what happens when you say ‘gl. . .’ or ‘cl. . .’ as the first letters of any of the many words that Derrida lists that begin with ‘gl’ or ‘cl’ – JHM.]) to each other, within each column and from one column to the other of what remained [ce qui est resté] infinitely calculable. (E1/G7)

Wow! If you can follow all those parentheses and lists you are a highly adept reader. The bottom line is that Derrida is now describing these two columns not as solid pillars but as two strange entities (strange because they are made of words not stones, as I imagined them to be) that constantly and dynamically interact in weird ways that are unimaginable as a static mental visual image. Each column envelops the other, turns itself and its fellow column inside out, like a glove or a sheath. What Derrida is, in my view, attempting to describe is the way the words, each with its own multiple and contradictory meanings, as put down in each column and in the interaction between each column with the other, violently subvert one another or contaminate one another by an irresistible contagion. This happens in a way that is ‘infinitely calculable’. That means, I take it, that you would never come to the end of calculating or specifying this interaction among the words just on page one of Glas. The final implication of this second passage is that you can name something in words that cannot be coherently imagined as a physical visual image, even though the reader is invited both by the format and by the spatial images in the words (for example, ‘Each column rises with an impassive self-sufficiency’) to struggle, though unsuccessfully, to see some encompassing coherent imaginary visual image generated by page one of Glas.

*

After the somewhat hallucinatory effect, on me at least, of my second passage, the third and final one is straightforward and simple, or almost. That may be because it is not by Derrida. It is a citation from Hegel’s Aesthetik. At the bottom of the left-hand column of page one, Derrida says his ‘legend’ does not ‘pretend to afford a reading of Hegel’s whole corpus, texts and plans [desseins], just of two figures. More precisely, of two figures in the act of effacing themselves, two passages’ (E1/G7). The following page indicates that one ‘passage’ from Hegel’s Aesthetik is about the ‘religion of flowers’, the other about ‘the phallic columns of India’. It is the second one that interests me, since it is an invitation to view the two columns of Glas in imagination in a certain way. The passage, Derrida tells the reader, comes in Hegel’s Aesthetics in the chapter on ‘Independent or Symbolic Architecture’. The passage is primarily a translation of what Hegel says, as the inserted long citation in Hegel’s German, not re-cited by me, demonstrates. We are reading in the version I cite the translation of a translation:

[The phallic column of India] is said to have spread toward Phrygia, Syria, and Greece, where, in the course of Dionysiac celebrations (according to Herodotus as cited by Hegel), the women were pulling the thread of a phallus that thus stood in the air, ‘almost as big as the rest of the body.’ [When I was in grade school in a very small town in upstate New York, my father was President of a tiny Baptist women’s college of two hundred students, Keuka College. Every May Day students from the college would dance in a circle around a maypole, two groups going in opposite directions and interweaving, each holding a ribbon attached to a pole. If it was done right, the pole would gradually be covered from the top down by the interwoven ribbons. I had no idea of the phallic significance or antiquity of this charming folk ritual, nor do I think the dancing girls did. It was just something you do on May Day. A maypole dance also appears in Hardy’s The Return of the Native. That dance’s meaning is made more or less explicit by Hardy. Hardy’s girls wreathe the pole in flowers from the top down20 – JHM.] At the beginning, then, the phallic columns of India, enormous formations, pillars, towers, larger at the base than at the top. Now at the outset – but as a setting out that already departed from itself – [A long exegesis would be required to unravel this observation. It fits Derrida’s assertions in many places in his work that the origin is always already self-divided. Difference or differing (différance) goes all the way down21 – JHM.] these columns were intact, unbreached [inentamés], smooth. And only later (erst später) are notches, excavations, openings (Offnungen und Aushöhlungen) made in the columns, in the flank, if such can be said. These hollowings, holes, these lateral marks in depth would be like accidents coming over the phallic columns at first unperforated or apparently unperforatable. Images of the gods (Götterbilder) were set, niched, inserted, embedded, driven in, tattooed on the columns [another of Derrida’s lists of synonyms that are not quite synonyms – JHM]. Just as these small caverns or lateral pockets on the flank of the phallus announced small portable and hermetic Greek temples, so they broached/breeched [entamaient] the model of the pagoda, not yet altogether a habitation and still distinguished by the separation between shell and kernel (Schale und Kern). A middle ground hard to determine between the column and the house, sculpture and architecture. (E2–3/G8–9)

Well! That gives me a lot of new different mental images to have at once when looking at those two columns on the first page of Glas. They are columns that are also phalluses. These phalluses are bare but are also encrusted with painful (to me at least, in imagination) incisions that are almost, but not quite, also habitations, like pagodas. They are also, as Derrida observes in the ‘Blurb’, like colossuses, huge statues of dead royalty, reminding me once more of those remains of a colossus in Shelley’s ‘Ozymandias’. The columns are also innocent, but not quite innocent, maypoles. What a lot of mental images to think of at once, in superimposition! The mind boggles.

*

A final question about those columns. Why are there two of them, side by side, each with the characteristics of Hegel’s mature phallic column from India? You will remember that ‘erections’, in all senses of the word, are a big topic in Glas. We know that this is to set Hegel against Genet in a scandalous juxtaposition, but other ways to do this can be imagined. The answer, in my judgement, is that the doubling of the columns on the page is an echo of what Freud (a big source for Glas throughout) says about the way the doubling in dreams of the phallus, or some penis symbol, equals its disappearance, the castration we men so (mostly unconsciously), Freud says, fear,22 and as all those incisions on Hegel’s phallic columns from India so painfully threaten. It hurts to think of it. The loss of the phallus, the head signifier, is of course one way to express the loss of systematic coherent meaning, the loss of the savoir absolu that gives certain comprehensive knowledge of ‘history, philosophy, political economics, psychoanalysis, semiotics, linguistics, poetics [. . .] of work, language, tongue, sexuality, family, religion, State, etc.’ (Glassary, 28). As Wallace Stevens puts it: ‘exit the whole/Shebang!’23

Please remember that I am still on page one. Think what a commentary on all 291 pages of Glas would be like. Interminable!

*

I conclude with a few words about Derrida’s use of the word reste (remains) as a noun or a verb. The word appears repeatedly in the ‘Blurb’ and on page one, as in the beginnings in mid-sentence of the two columns: ‘what, after all, of the remains(s), today, for us, here, now, of a Hegel?’ [Why a Hegel? To call attention to the homology in the French pronunciation, developed a moment later, of Hegel and aigle (eagle)? – JHM.]; ‘“what remained of a Rembrandt torn into small, very regular squares and rammed down the shithole” is divided in two. / As the remain(s) [reste]’ (E1/G7). Other appearances of ‘reste’ on page one are ‘remains(s) to be thought’; ‘The incalculable of what remained calculates itself ’; ‘the infinite circulation of general equivalence relates each sentence, each stump of writing [. . .] to each other, within each column and from one column to the other of what remained infinitely calculable’; ‘Of the remain(s), after all, there are, always, overlapping each other, two functions.’ [He goes on to say these two functions are the fall to the tomb and the simultaneous erection – JHM.] In the ‘Blurb’: ‘What remains of absolute knowledge?’ (Que reste-t-il du savoir absolu?) (Glassary, 28; ‘Blurb’, verso).

The meanings of reste are, as Derrida says, infinitely calculable. I could never have done with them. Nevertheless, I terminate, without really terminating, with a few final remarks. By the way, we have ‘rest’ in English, meaning ‘the missing parts’, as in ‘Where is the rest of me?’ or ‘What did you do with the rest?’ ‘Rest’ also means a period of relaxation, as in ‘I think I’ll take a rest now.’ The French word reste is clearly an example of a ‘double antithetical word’. It not only has many meanings, but those meanings contradict one another. Reste means ‘remains’ in the sense of dead body, as in ‘The remains were laid to rest.’ It means what is left over, perhaps something of great value, though now in fragments. It means both a fall to the tomb and the erection of something that is still there, even though in morsels. The mind goes back and forth between these two extremes. To initiate that oscillation is perhaps the most important feature of Derrida’s use of reste. It is a key word in Glas.

I return in conclusion to my initial question about what actually happens in the act of reading. What takes place when I read Derrida’s iterations of reste, in its various contexts in the insert and on page one of Glas, is that bit by bit there arises in my mind a composite image, a collage or montage, of a pile of debris such as you might find in the town dump or in a garbage can or in a waste basket; of faeces; of a Rembrandt torn into regular squares; of the works of Hegel similarly fragmented; of a dead body (Derrida’s own: he was obsessed with the question of his own remains, in all senses, including his unpublished manuscripts); of a fragmented poster of an imperial German eagle; of debris falling and then rising again as a tower and simultaneously as a colossus.

I rest my case, in all senses of ‘rest’.

NOTES

1.John Keats, ‘On First Looking into Chapman’s Homer’, Poetry Foundation, available at <https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems-and-poets/poems/detail/44481> (last accessed 15 December 2016).

2.The essays on Anthony Trollope’s Framley Parsonage and Wallace Stevens’s ‘The Motive of Metaphor’ are forthcoming in Ranjan Ghosh and J. Hillis Miller, Thinking Literature Across Continents, Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2016; I discuss Yeats in ‘Cold Heaven, Cold Comfort: Should We Read or Teach Literature Now?’, in Paul Socken (ed.), The Edge of the Precipice: Why Read Literature in the Digital Age?, Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2013, pp. 140–55; the essay on Derrida’s Otobiographies appeared as ‘How to Read the Derridas: Indexing moi et moi’ in a special number on A Decade after Derrida of Oxford Literary Review, 36: 2 (2014), 269–73.

3.Jacques Derrida, Glas, Paris: Galilée, 1974.

4.Jacques Derrida, De la grammatologie, Paris: Minuit, 1967; Jacques Derrida, Of Grammatology, trans. Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, Baltimore and London: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1976.

5.Jacques Derrida, Glas, trans. John P. Leavey, Jr. and Richard Rand, Lincoln, NE and London: University of Nebraska Press, 1986. Page references will henceforth be given in the text to this translation and to the Galilée edition preceded by E and G respectively.

6.John P. Leavey, Jr., Glassary, Lincoln, NE and London: University of Nebraska Press, 1986; henceforth Glassary.

7.See ‘Galileo Galilei’, Wikipedia, available at <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Galileo_Galilei> (last accessed 15 December 2016).

8.An English translation of the ‘Blurb’ is given in Glassary, p. 28.

9.Jacques Derrida, ‘Tympan’, in Marges de la philosophie, Paris: Minuit, 1972, pp. i–xv; Jacques Derrida, ‘Tympan’, in Margins of Philosophy, trans. Alan Bass, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1986, pp. ix–xxix.

10.Paul Robert, Dictionnaire alphabétique & analogique de la langue française, ed. Alain Rey, Paris: Société du Nouveau Littré, 1976, p. 787.

11.See ‘Aufheben’, Wikipedia, available at <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aufheben> (last accessed 15 December 2016).

12.Paul de Man, ‘Conclusions: Walter Benjamin’s “The Task of the Translator”’, in The Resistance to Theory, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1986, p. 87.

13.See ‘The Judas Window’, Wikipedia, available at <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Judas_Window> (last accessed 15 December 2016).

14.See ‘Jalousie Window’, Wikipedia, available at <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jalousie_window> (last accessed 15 December 2016).

15.L. 2. For the whole sonnet, see Percy Bysshe Shelley, ‘Ozymandias’, The Literature Network, available at <http://www.online-literature.com/shelley_percy/672/> (last accessed 15 December 2016).

16.Walter Benjamin, The Arcades Project, trans. Howard Eiland and Kevin McLaughlin, prepared on the basis of the German volume, ed. Rolf Tiedemann, Cambridge, MA and London: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1999.

17.Jean-Paul Sartre, Saint Genet, comédien et martyr, Paris: Gallimard, 1952; Jean-Paul Sartre, Genet, trans. Edmund White, corrected edn, London: Picador, 1994. I taught myself back in the 1950s good enough French to read this book before it was translated, so important did it seem to me then to learn what Sartre said about Genet.

18.See note 2 above.

19.See Jacques Derrida, ‘La Loi du genre/The Law of Genre’, trans. Avital Ronell, Glyph, 7 (1980), 176–232, especially 190–2, in French; 217–19, in English. See Simon Morgan Wortham, The Derrida Dictionary, London: Continuum, 2010, p. 76: ‘an invaginated text is a narrative that folds upon itself, “endlessly swapping outside for inside and thereby producing a structure en abyme.” [Derrida] applies the term to such texts as Immanuel Kant’s Critique of Judgment and Maurice Blanchot’s La Folie du Jour. Invagination is an aspect of différance, since according to Derrida it opens the “inside” to the “other” and denies both inside and outside a stable identity.’

20.See Thomas Hardy, The Return of the Native, Book Six, ch. 1, available at <http://www.gutenberg.org/files/122/122-h/122-h.htm> (last accessed 15 December 2016).

21.See Derrida, ‘La différance’, in French, in Marges de la philosophie, pp. 1–29; Derrida, ‘Différance’, in English, in Margins of Philosophy, pp. 1–27.

22.‘This invention of doubling as a preservation against extinction has its counterpart in the language of dreams, which is fond of representing castration by a doubling or multiplication of a genital symbol’ (Sigmund Freud, ‘The Uncanny’, trans. Alix Strachey, then considerably modified, in The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works, under the general editorship of James Strachey, in collaboration with Anna Freud, assisted by Alix Strachey and Alan Tyson, London: Vintage; The Hogarth Press and the Institute of Psycho-Analysis, 2001, vol. XVII, p. 235).

23.Wallace Stevens, ‘The Idea of a Colony’, ll. 6–7, Part IV of ‘The Comedian as the Letter C’, in The Collected Poems, New York: Vintage Books, 1990, p. 37.