‘A very black and little Arab Jew’:

Experience and Experimentation

or, Two Words for Jacques Derrida

Julian Wolfreys

I am trying to disinterest myself from myself to withdraw from death by making the ‘I’, to whom death is supposed to happen, gradually go away, no, be destroyed before death come to meet it, so that at the end already there should be no one left to be scared of losing the world in losing himself in it, and the last of the Jews that I still am doing nothing here other than destroying the world on the pretext of making truth, but just as well the intense relation to survival that writing is, is not driven by the desire that something remain after me, since I shall not be there to enjoy it in a word, there where the point is, rather in producing these remains and therefore the witnesses of my radical absence, to live today, here and now, this death of me, for example, the very counterexample which finally reveals the truth of the world such as it is, itself, i.e., without me, and all the more intensely to enjoy this light I am producing through the present experimentation of my possible survival, i.e., of absolute death, I tell myself this every time I am walking in the streets of a city in which I love . . .

Derrida, ‘Circumfessions’ (1993: 190–1)

Jacques Derrida.

I speak the proper name.1 How do you hear this? What is your ‘experience’ of this word? What does memory conjure? What does it call to mind or banish? How are you called, by the name ‘Jacques Derrida’? How are you called, in the name of Jacques Derrida? Before you rush to decide on an answer, before you decide, or believe you have already decided, in your response or non-response (presumed or otherwise) to the other, on your answer, pause. Hesitate before taking a step, before refusing to enter or refusing entrance, remaining on the side of the inhospitable. It may well be that you believe your response to be the affirmation of a non-response. Someone speaks up, saying, ‘I am not called by this name.’ ‘This proper name has nothing to do with me.’ ‘I have nothing, I want nothing to do with this name.’ I am, if you will allow, experimenting here with x number of voices, ventriloquising them, paraphrasing or translating from experience or memory – and perhaps from anticipation of what might be coming at my conclusion, or, more undecidably, from an act of telepathy in which I am engaging just at present. (How could you tell?) Or, more radically, these variations on a theme, being examples of a performative speech act underlying every response that affirms itself as a non-response, which affirms its response just as this despite all protestation to the contrary, in enacting the role of non-respondent; and refusing, as it were, all correspondence with the name, refusing to accept the name, returning, or seeking to return the name to sender (but wait a minute, one cannot refuse the summons, one cannot avoid being served); all such variations, so many riffs, play on the proper name, and in this, they are called. The subject who believes he or she refuses or has refused the name is deluding him- or herself – for every act of non-response is not the avoidance, the denial, it likes to delude itself that it is.

That said, allow me to reiterate these two words, the proper name:

Beyond the possible recognition of a proper name as such, I am saying nothing. For the moment, here, now, at this very moment. That’s not saying a lot. And yet, it speaks volumes. Though saying nothing more, nothing as yet, nevertheless there are those of you for whom the name speaks volumes, or so you believe. You will supply your own contexts from experience or memory, even, and perhaps especially if your contexts are those bricks in a wall you employ to build a fortress that keeps the name, like the foreigner, the stranger, the immigrant, the ‘little black and very Arab Jew’ (Derrida 1993: 58) at bay, on a border, some limit of your own making. You will supply your own contexts, whether or not you believe yours is a refusal, a non-response, whether or not you think you accept the proper name. However you align yourselves, however and in whatever ways you recognise, accept, refuse, associate, disassociate, the proper name; even if you have never heard the name until today, the name calls on you. The name is given. That it is a name is, as we say in English, a given, though not necessarily a gift. The name is nothing. It delivers nothing, nothing is given, even though the idea of a proper name, of ‘having’ a proper name, is a ‘given’. Yet something comes to be. The arrival of a name, the very principle of its arrival – and names always arrive, whether or not you recognise them; though you might not know the name, you apprehend in some fashion, on hearing or seeing, that this therefore will have been a proper name – produces in our cultures an effect, having to do with the following: singularity, property, propriety, alterity, the self and other, the subject, identity. So, the proper name, say it once more (I’ve written it again):

Jacques Derrida.

You may have noticed, some of you, that I have proposed a number of hypotheses, all of them connected in one way or another, each of them threaded through the matrix of the proper name. Even as those hypotheses begin to define without determining, the shape of the proper name, and our assumptions concerning the identity and function, the purpose or economy of the proper name; so too, the proper name, as idea, as presumed and shared concept across what we think of as ‘our’ cultures is, properly speaking, a matrix, it generates, it engenders. This is still not to speak of context, or at least the contexts I assume are already presumed, assumed, assembled, contrived, recovered. Yet, I have risked certain hypotheses, without indicating my intentions (supposing I know them myself), in order to begin carrying out a small experiment. The experiment, put simply, is to send the name, to deliver this name to you, to deliver that proper name, which, for a number of you (I cannot possibly know or guess, and do not intend to take a head or hand count, this has nothing to do with data, or the quantifiable) has already, as I’ve hypothesised, been delivered. It strikes me that at this very moment, I could abandon the keynote, give up my delivery, and invite you all for the rest of the time allotted to engage in a supplementary experiment: to write in brief, as if this were an exam as well as an experiment, about your experience of the proper name. Not simply the proper name in general, but the name I have re-delivered today, this morning. To recall just the first of my questions: how do you hear it? Thus, the experiment might begin. Were it not for the fact that it has already begun, that it has always already begun as soon as any of us is named, as soon as any of us receives our own proper names. To name is an experiment, it is an act of experimenting with the self, with identity. For to give the name is to introduce the animal to its subjectivity, a subjectivity it will only belatedly begin to reflect upon. We have language inflicted on us; we suffer under the sign, the signature, of the proper name; the proper name is ours on sufferance. This is a digression, however; having announced – confessed – my experiment, I will say unequivocally, nothing could interest me less than seeing the experiment through to some conclusion. The very idea of a conclusion is itself, for me, risible. For this matter of experimentation in the name, experimentation with, on, in the name of, the proper name, has more to do, as my questions, my provocations, my hypotheses and analyses of response and non-response, engagement and avoidance, might suggest, with experience. We experience the proper name, we experience proper names, as no other word.

Such experience (and I’m not done with this word just yet in relation to experiment), along with all the modalities that ‘experience’ implies, all those modalities I have just named (non/response, engagement/avoidance, and so forth) have to do with ‘exappropriation’. Not expropriation, but exappropriation, a neologism invented by one Jacques Derrida for the purpose of continuing a career-long experiment with, and experience of the proper name, beginning at least with the essay ‘Signature événement contexte’, from his 1972 publication, Marges de la philosophie, and lasting beyond his death, in comments made in a posthumous translation, For Strasbourg. (A parenthesis: all translations are posthumous inasmuch as they take place in the structural absence of the author. This is the risk the translation takes, whether or not the author is ‘actually’ living or dead; every translation behaves as if the author were dead, this is its inescapable necessity and responsibility. The words translated are always remains; and however faithful the translation, there is always a remainder, even, and perhaps especially, because translation bears witness, taking place in the name of the author, exactly in order to seek to preserve the author’s proper name. The proper name has its chance only in being no longer what it is but being, however lovingly, improperly reinscribed, in, or on, the tongue of another. Translators always know more about death than any author.) Here is Derrida on ‘exappropriation’ and the name, in response to a question from Jean-Luc Nancy concerning the difference between expropriation and exappropriation:

What I wished to say with exappropriation is that in the gesture of appropriating something for oneself, and thus of being able to keep in one’s name, to mark in one’s name, to leave in one’s name, as a testament or an inheritance, one must expropriate this thing, separate oneself from it. This is what one does when one writes, when one publishes, when one releases something into the public sphere. One separates oneself from it and it lives, so to speak, without us. And thus in order to be able to claim a work, a book, a work of art, or anything else, a political act, a piece of legislation, or any other initiative, in order to appropriate it for oneself, in order to assign it to someone, one has to lose it, abandon it, expropriate it. That is the condition of this terrible ruse: we have to lose what we want to keep and we can keep only on the condition of losing. It’s very painful. The very fact of publishing is painful. It departs, one knows not where, it bears one’s name, and – it’s horrible – one is no longer even capable of reconstituting it oneself, not even of reading it. That’s exappropriation, and it applies not only to those things we speak of with relative ease, that is, literary or philosophical works, but to everything, to capital, to the economy in general. (Derrida 2014: 24)

As soon as there is the proper name, there is exappropriation. The parent, the priest, loses the very thing it seeks to claim or to keep, the animal, on which it confers identity and subjectivity by the act of giving the proper name. As soon as there is the proper name, as soon as the fiction of singularity is inscribed, there takes place exappropriation. This is the experience. This is our experience in the name of the proper name. Allow me therefore, once again, to reiterate this particular proper name:

Jacques Derrida.

Thus far I have sought to let the name resonate unremarkably, leaving it for you to consider, reflect on, experience, and perhaps to experiment with a little, the experiment shifting as I have spoken and as you will now be reading. I cannot control any of this. I have sought, as part of my small and admittedly insignificant experiment – refusing to accept any methodological premises or theoretical models, and insisting instead on the primacy of experience, and, along with that, all that cannot be predicted, programmed, measured, ordered – to embody, if you will, or to perform that which hypothetically speaking the proper name makes possible. Of what it makes possible, I might say, in the name of Jacques Derrida. When I write, as I wrote ‘in the name of Jacques Derrida’ (last Tuesday shortly before 1 p.m.), and what I say, when I say ‘in the name of Jacques Derrida’, I hear this phrase two ways at least. On the one hand, in a wholly conventional way, I am speaking, I am writing in Derrida’s name. That which I articulate – and we’re not even talking about matters of style so-called, much less ‘school of thought’, ‘literary theory’, poststructuralism (sic), or any other -ism – is in Derrida’s name, on behalf of ‘Jacques Derrida’. On the other hand, to raise the stakes and risk a strong reading, I am excavating, experimenting with what takes place in Derrida’s name, what comes to pass in the experience of the name Jacques Derrida. A problem arises immediately though. When I say I am seeking to say something in Derrida’s name or on behalf of Derrida, a confusion might emerge. Am I speaking for the man or the text signed in his name? The two are only homologous to a degree. The one signs the other, the other bears the name. Whenever I have said

Jacques Derrida,

which is it, do you imagine, I have been speaking of – citing, referring to, using, giving you? I have not said. I might be talking of the person (cultural identification, pronominal signifier, inscription of the biological entity), the person’s ideas (synecdoche, metonymy), the person’s texts, or a particular text, not even an entire essay or a book, a lecture or article, but a paragraph, a phrase, a passage, an extract. Indeed, my experiment has wagered in part on the hypothesis that, in stating the name, keeping citation and reference to a minimum, you would, to varying degrees, presume the individual, the human animal on which the name is inscribed, thereby providing a camouflage of individuality, selfhood, singularity, and that you would, of your own accord, conflate the name with the writing; this is to say, in part my trivial experiment was to imagine you inventing the figure that stands behind the texts and not wondering whether I was in fact speaking of one or the other, as if there were an inevitable economy, a modality of metonymic or synecdochic substitution taking place. And, I have to admit, I nudged you toward the self – albeit an estranged, perhaps defamiliarised figure of the self – rather than the text. Often, it must be said, the things we believe we understand are the result of that aspect of experiment that is akin to sleight of hand. When I spoke earlier of a ‘little black and very Arab Jew’ I called to mind an image, a representation conjured by Jacques Derrida, an auto-representation, the self as other, the self speaking on behalf of, bearing witness to the self as other, in a place where the other cannot speak, but stands as mute testimony to the experience of racism and anti-Semitism, in one of fifty-nine otherwise unpunctuated sentences or what are called, by the author who exappropriates himself knowingly, ‘periphrases’, small more or less cryptic, confessional and autobiographical traces of the self. As early as Marges de la philosophie Derrida had observed how the proper name in Aristotle, specifically the Rhetoric (III, V) (‘recourir aux noms propres, c’est éviter le détour de la périphrase . . .’ / ‘using proper names evades the periphrastic detour . . .’ (1972: 328/1982: 247; translation modified)) served to control reception, which for Aristotle was the correct thing to do.

Before returning to periphrasis as experiment on the name and experience of the self, and looking at an extract from one of the periphrases in question, I wish though, to offer a short commentary on Derrida’s understanding of the proper name. This is so as to offer an ‘internal’ parergon, an inner frame within which the proper name might be situated as that around which I have been writing, without identifying with any certainty to what or whom the proper name belongs. I can do no better than to cite John D. Caputo:

The whole idea of a proper name, its very ‘condition of possibility,’ is to come up with a signifier that is just that particular person’s own signifier, the sign of just that one person, of that singular one and of no one else, to be that singular one’s own personal sign. In a proper name, only that person answers to that name and that sign picks out only that one person. That is what we desire, what we love, so that the proper name is a work of love. But that is impossible (which is why we love and desire it all the more), so that the very condition under which the proper name is possible makes it impossible. [Recall, if you will, Derrida, on exappropriation, and the horror of writing and publishing – JW.] For were the sign to be utterly proper, absolutely unique and idiomatic, no one would understand it, and we would not even know it was a sign rather than just a noise or a scratch on a surface. To be a name it must be a signifier, and to be a signifier it must be significant. And to be significant it must be repeatable. We must be able to sign this name again and again, call it or be called by it, use it again and again, including when its referent is absent [either structurally absent, not in the room, or in the country, for example, or as Derrida has it, radically absent, which is to say dead – JW.]. A signifier must be woven of repeatable stuff or be consigned to unintelligibility. But if this signifier is repeatable. It is assignable to others [or to books, works of art, and so forth – JW.] who can bear the same name, so that its propriety is compromised. It cannot be an absolutely proper name, not if it is to be a proper name. A proper name is an attempt to utter something repeatable about the unrepeatable. (Caputo 2000: 40)

Something takes place in the proper name, or, one is tempted to say in the name of: this one or that one, this or that text. Yet, as soon as the name is signed, supposed guarantor of some unique property, the signatory standing in for the subject whose proper name this is assumed to be, in order for that signature to operate in its singularity, it has to be capable of being spirited away; indeed, it is always already haunted from within by its own iterability, the paradoxical quality by which, in the name of which it might be added, the proper name is no longer proper to itself. We might just illustrate this in part with a proper name, a surname, such as Wiewiórka, which some of you will know means squirrel. Červenka, to take another proper name, a Czech example, means robin, which in Polish is Rudzik, also a proper name. (Names, like birds, have no borders.) The proper name very quickly slips away from itself, from any propriety or formal qualities. In names such as these, the human’s individuality is partially erased, its animality the trace that haunts that illusion.

It is not necessary, however, in exploring what appears as an experiment in the proper name to dwell further. We need only return to the point almost of departure, and so start once more with the proper name, the two words that have insisted:

Jacques Derrida.

When I wrote this proper name, to what, to whom, was I referring? Was I in fact not referring but citing? Alluding? Acknowledging, perhaps, remembering, mourning, bearing witness. All of these, any of them, each iterable occurrence in a different register, another modality of representation, of presentation without representation. Of course, Jacques Derrida has, in his writings, played on his own name, as some will know; this is not the place to offer a recapitulation of such performative tropes, to suggest different headings. My small experiment, this gestural tic I have assumed, a prod, a provocation, an allergen it might just be; my experimental foray in speaking so as to make possible for you an experience that I can neither govern nor control, still insists on that which, in its revenance, refuses its proper status, its propriety – and so performs its own impropriety, enacting its own exappropriation, exappropriation as the haunting trace within the proper name itself (as though all proper names were suddenly betrayed, as though we found ourselves plagued by some restless spirit). It may be that I am speaking of, in the name of the man, the author; or it may be that I am speaking of a text – not merely a text on which this name is inscribed as its author, but a text that is named Jacques Derrida. Or, third possibility, I may be alluding to, signifying both, man and book, the former writing himself within, and against a book with such a title. And what a title! I have not yet let you in on what – or who – I am calling what or who calls when I write, when I say Jacques Derrida. The name not only is nothing, not

in any case . . . the ‘thing’ that it names, [it is] not the ‘nameable’ . . ., but also [it] risks to bind, to enslave or to engage the other, to link the called, to call him/her to respond, . . . even before any freedom. . . . And still, if the name never belongs originarily and rigorously to s/he who receives it, it also no longer belongs from the very first moment to s/he who gives it. . . . the gift of the name gives that which it does not have, that in which, prior to everything, may consist the essence, that is to say – beyond being – the nonessence of the gift. (Derrida 1995: 84–5)

As scrupulously as I have tried – and failed – neither to cite, refer, allude nor acknowledge in any but the most minimal manner (which is still the most violent, with the nudity of command or injunction) this or that or the other Jacques Derrida, my experience of the proper name still insists on binding the other to me; my experiment has involved calling, demanding unreasonably a response. But this experiment has been engaged, in the name of Jacques Derrida, in order to announce that which escapes, or exceeds any ‘economical formalization’ (Derrida 1995: 85), any methodological systematisation – I have wagered everything on challenging, by experimenting with the minimal requirements of the proper name and all that comes to put in place the proper name in ‘our cultures’, in ‘our traditions’, so as to withdraw in the face of ‘economical formalization’, or theorisation so-called, so as to remain with, and allow to remain a certain ‘reserve of language, almost inexhaustible’ (Derrida 1995: 85) that the presumed propriety and containment of the ‘proper name’ serves most starkly to reveal, despite the intention with which it is given, despite the desire that accompanies this gift of nothing that calls, binds and enslaves.

Which returns me once more, returning to me as just the name

Jacques Derrida,

whether ‘person’ or ‘book’ (I will not say ‘text’, for both ‘person’ and ‘book’ are textual, textile, and for which the proper name merely serves as something ‘elliptical, taciturn, cryptic . . .’ (Derrida 1995: 85), thus:

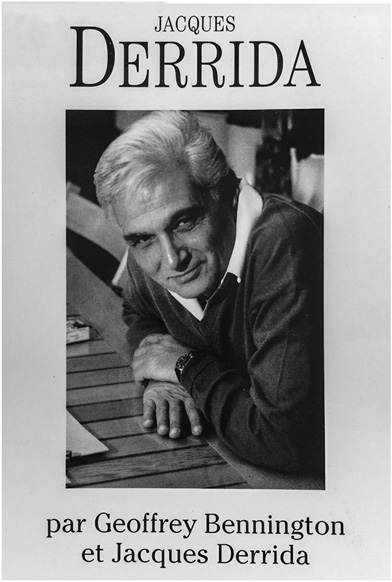

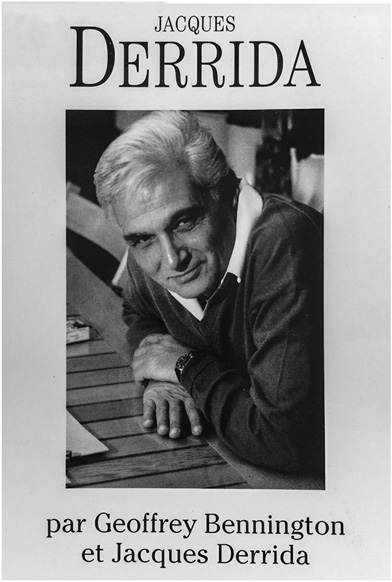

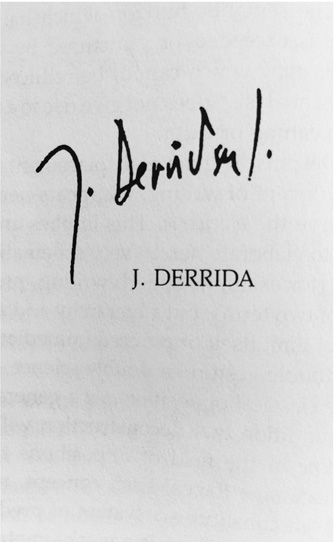

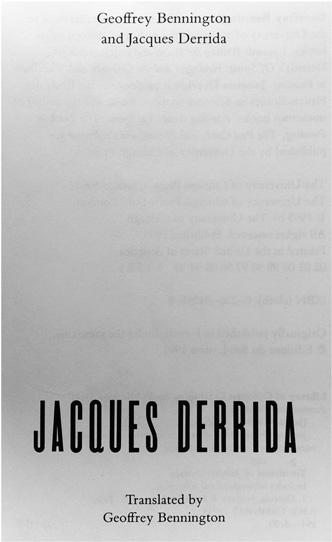

Figure 12.1

Figure 12.3

Taking these pages, the cover, on which the name appears twice on every occasion, and on two occasions the proper name ‘improperly’ escapes its purpose to give itself as other than itself, as title and, no longer, strictly speaking, ‘author’, I would like you to ask yourselves, to which – to book or person – have I been alluding, referring, citing, calling? To which have I bound myself? To one more than the other? Both? And what have I given away, giving something that stricto sensu is not mine to give, is nothing as such? Can you tell? Is this possible? Someone, not me, would need to wish to engage and so bind themselves to a more or less rigorous reading of the ‘uses’ of Jacques Derrida in this paper. Someone would have to try, having been called by the name, finding themselves addressed, called, as it were, in the name of Jacques Derrida. (Though which one, we will never know; even were I certain, I could not say for sure; this is my experience, this is why, in memory of my experience and the experiences of the proper name to come, I have experimented here, today, in the name of Jacques Derrida.) And this experiment would have to begin, once again with the experience, confronted all the while with that which is undecidable, and which therefore, haunting every iteration, would withdraw, even as it undoes all that is proper in the proper name.

However much a few of you, some, or even all of you may believe this so much frivolity, irresponsibility, mere word games, grant me the possibility that I am seeking to direct you to something in the experiment having to do with experience, an experience to which each of our proper names attests. This paper is an experiment inasmuch as it has sought from the outset to adopt a course without being sure of the outcome or destination. This is not an experiment in the sense of testing out hypotheses. I have put forward particular hypotheses, it is true. But this has been done in order for you to test them if you wish, leave them alone if you don’t. The experience of that to which you are attending has at its heart the merest chance that you may wish to pursue the experiment in your own way.

I have, you may have noticed, used the word ‘experience’ repeatedly, alluded to experience, often in conjunction with or adjacent to ‘experiment’. Both ‘experiment’ and ‘experience’ derive from the same Latin source, experiri, meaning, quite simply, ‘to try’. In thinking about ‘experiment’ for this paper, this conference, in trying out various ideas, rejecting many, my experience was one that led me to consider, as the fiction of a starting point, an artificial ‘origin’, or what George Eliot calls ‘the make believe of a beginning’ (Eliot 2014: 3), which she insists all men need, I searched Derrida’s texts, the texts that bear the name ‘Jacques Derrida’, for the word ‘experiment’. It is used relatively infrequently. Experiments are tried in telepathy by the Russians and Americans, or by Freud, observes Derrida in ‘Telepathy’ (Derrida 1988: 236). It is used by Lacan, Derrida reminds us, in speaking of experimentation on humans and animals (Derrida 2009: 156–7). Or it is used to describe Hegel’s hypotheses on sense-certainty (Derrida and Ferraris 2001: 112). It is rarely used by Derrida about his own writing. Experience, however, as experiment’s other, its countersignature, is everywhere woven into the weft of the Derridean text, in the texts signed by this singular proper name.

Which brings me to that inaugural passage, from which I departed but which now returns, as if the experiment required that one start, again. As if one had never left, stepped over the threshold of the proper name.

The book that is named Jacques Derrida, which is written, first in French, then in English, by Geoffrey Bennington and Jacques Derrida, is first of all an experiment. It is an experiment concerning the possibility or impossibility of methodological systematisation. Put bluntly, this experiment, which the putative authors describe as presupposing a contract, ‘itself established or stabilized on the basis of a friendly bet’ (Bennington and Derrida 1993: 1) concerned the attempt on the part of Geoffrey Bennington to ‘describe, according to . . . pedagogical and logical norms . . . if not the totality of J. D.’s thought, then at least the general system of that thought’, without ‘any quotation’. Bennington, the brief preface continues, ‘would have liked to systematize J. D.’s thought’ (Bennington and Derrida 1993: 1). You know the kind of thing. You must do, some of you at least. For there are some of you who assume, judge, prejudge or prejudice yourselves by speaking of some, or all, of the following: literary theory, theory, critical methodology, structuralism, poststructuralism (with or without the hyphen), or, raising the stakes just a little more, ‘deconstruction’, as if this named a theory, a system of thought, a methodology. However, given this experiment, this wager or contract, this is only half the story. For while Bennington’s text, that which occupies in the book Jacques Derrida the upper two-thirds of most of the pages, is just this attempt to describe and so systematise, the bottom part of the page consists of those fifty-nine periphrases, to which I have already alluded. Derrida’s stake in the work is ‘to show how any such system must remain essentially open, [the] undertaking [of systematisation] . . . doomed to failure from the start . . . . In order to demonstrate the ineluctable necessity of the failure’. Derrida wrote something ‘escaping the proposed systematization, surprising it’ (Bennington and Derrida 1993: 1). This ‘something’ concerns, touches on, autobiography, the mother, the mother’s illness, the sister, St Augustine (at one time, someone ‘very black and little Arab’). A typical periphrasis focusing on his mother’s illness begins: ‘April 10, 1990, back in Laguna, not far from Santa Monica, one year after the first periphrasis, when for several days now I have been haunted by the word and image of mummification . . .’ before shifting to the recollection of a dream: ‘this does not stop me from walking out in the street, arm in arm with a young lady, under an umbrella, nor from seeing and avoiding, with a feeling of vague guilt, my Uncle Georges’ (Derrida 1993: 260–1). The text by Jacques Derrida, to which he puts his name, exceeds that written by Geoffrey Bennington, that which is titled Jacques Derrida, whether in the French or the English edition (the proper name moves, its register different in each language, but it remains untranslatable). Indeed, both upper and lower parts of the text are titled Jacques Derrida, even though one is ‘by’ Jacques Derrida about a certain Jacques Derrida, and other is about the ‘thought’ of Jacques Derrida and not the life, the person of, Jacques Derrida. This is the experiment.

In this experiment comes the statement cited above. I will not repeat this aloud, but allow it to appear, for you, each and every one, to read, or not read, to experience or to seek to avoid the experience, to engage with, take up, or to believe you can ignore (rather like the graffito that reads ‘Do not read this’ [if you’ve read it, it’s too late; if you haven’t, it is impossible to obey]):

I am trying to disinterest myself from myself to withdraw from death by making the ‘I’, to whom death is supposed to happen, gradually go away, no, be destroyed before death come to meet it, so that at the end already there should be no one left to be scared of losing the world in losing himself in it, and the last of the Jews that I still am doing nothing here other than destroying the world on the pretext of making truth, but just as well the intense relation to survival that writing is, is not driven by the desire that something remain after me, since I shall not be there to enjoy it in a word, there where the point is, rather in producing these remains and therefore the witnesses of my radical absence, to live today, here and now, this death of me, for example, the very counterexample which finally reveals the truth of the world such as it is, itself, i.e., without me, and all the more intensely to enjoy this light I am producing through the present experimentation of my possible survival, i.e., of absolute death, I tell myself this every time I am walking in the streets of a city in which I love . . . (Derrida 1993: 190–1)

I remarked earlier that Derrida rarely speaks or writes of experiment. Here is an exception. The passage exceeds the proper name by confronting the self’s ownmost condition, the future memory, the memory to come of the self’s death, the death, not of the author, but of the ‘I’, of saying ‘I’. One of a possibly infinite, certainly uncountable number of selves, who may well happen to bear the name Jacques Derrida, but whose name could equally be any of ours, mine, yours, his or hers, seeks in anticipation of that death that is ‘supposed to happen’, to lose consciousness of selfhood, of the ‘I’. Derrida writes ‘supposed’ because none of us knows; I may know that I am dying, I certainly know that I will die, as I know, one day, each and every one of you, and everyone you know, will die – this future is guaranteed, it is just the when and the how that remain to come, unknowable as such. The ‘I’ seeks to remove itself from the scenario it anticipates but cannot experience. But it does so by writing. For writing is what remains, it remains to come, the trace, not the presence. The trace is the remains of the self, what remains to come, to return, to be read, misread, not read. In a word, iterable; in another, revenance itself, a revenance that reminds the reader that the itself is not there, in the writing, in the signature, in the proper name, even though the proper name is of the order of writing, despite its apparent singularity.

For ‘I’ exceeds the singularity, the weight, the burden, of the proper name. ‘I’, more properly that which expresses the self, yet which is irreducible to any particular self, but which is the most naked affirmation of Being, escapes the proper name. Derrida’s experimentation, the ‘present experimentation of my possible survival’, is just this writing of the self, an ongoing process, an experience of the self, the ‘I’, in writing, as the trace itself, anticipating itself as the not-self, the non-essential trace, remainder, revenant that lives on, sur-viving, ‘living’ beyond mere physical, corporeal, animal existence, beyond the death of the one who bears the proper name. Derrida erases the proper name in the name of ‘I’, L’Innommable, the unnameable. (It is as if, I like to imagine, another proper name were being called, came calling, was cited without being cited, cited indirectly; it is as if, imagine it, Beckett were cited, called, referred to, alluded to; as if Beckett had come calling here, had left in this word his calling card, and this were Derrida’s response.) No proper name, no one chained to the name, yet in the face of death, ‘I’ presents itself even in the absence, the structural or radical absence of the one who writes, the ‘I’ continuing to arrive even post-mortem. ‘I’ survives absolute death. This is, to reduce it to its starkest element, what takes place as experiment and experience in the name of Jacques Derrida, in Jacques Derrida, exceeding and escaping systematisation, totalisation and even life. And because there is no proper name that can encompass, frame or enslave the ‘I’, there remains, as there remains to come for each and every ‘I’ who speaks, who reads the ‘I’ of an other, the singularity of experience in intimate relation to the world, at once singular and also universal; or, as a certain Jacques Derrida has it, thereby countersigning with his trace as the trace of a survival ahead of and beyond his death, though unnameable as such, ‘I’ bespeaks a ‘universal pronoun, but of so singular a universality that it always remains, precisely, singular. The function of this source’, writes Jacques Derrida, speaking to us from beyond the grave, ‘which names itself I is indeed, within and without language, that of a singular universal’ (1982: 281).

I can’t go on.

I’ll go on.

Or, in the words of Gloria Gaynor, I will survive.

NOTE

1.A version of this chapter was first delivered as a keynote address on 19 May 2016, at the Seventh Between.Pomiędzy Festival and Conference, Sopot-Gdynia-Gdańsk, Poland, 16–21 May 2016. I would like to thank the organisers, David Malcolm, Monika Szuba and Tomasz Wiśniewski, for all their hard work and for being such gracious hosts.

Bennington, Geoffrey and Jacques Derrida (1993), Jacques Derrida, trans. Geoffrey Bennington, Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Caputo, John (2000), ‘For the Love of the Things Themselves: Derrida’s Phenomenology of the Hyper-Real’, Journal of Cultural and Religious Theory, 1: 3 (July), 37–60.

Derrida, Jacques (1972), Marges de la philosophie, Paris: Minuit.

Derrida, Jacques (1982), Margins of Philosophy, trans. Alan Bass, Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Derrida, Jacques (1988), ‘Telepathy’, trans. Nicholas Royle, Oxford Literary Review, 10, 3–41.

Derrida, Jacques (1993), ‘Circumfessions’, in Geoffrey Bennington and Jacques Derrida, Jacques Derrida, trans. Geoffrey Bennington, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, pp. 3–315.

Derrida, Jacques (1995), On the Name, trans. Thomas Dutoit, Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Derrida, Jacques (2009), The Beast and the Sovereign, vol. I, trans. Geoffrey Bennington, Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Derrida, Jacques (2014), For Strasbourg: Conversations of Friendship and Philosophy, ed. and trans. Pascale-Anne Brault and Michael Naas, New York: Fordham University Press.

Derrida, Jacques and Maurizio Ferraris (2001), A Taste for the Secret, trans. Giacomo Donis, ed. Giacomo Donis and David Webb, Cambridge: Polity Press.

Eliot, George (2014), Daniel Deronda, ed. Grahame Handley, intro. K. M. Newton, Oxford: Oxford University Press.