HAPPITRONOMICS

In the chapter History of a Belief: Trickle-up Economics, I mentioned that there were really two premises on which capitalism was based: firstly, that it makes people richer; and secondly that wealth enhances human wellbeing. Unless we can demonstrate this second premise, then there is no point to getting richer. The exploration of the relationship between money and happiness is a tricky one. People who are both professors of psychology and economics are a bit thin on the ground, so there are two ways to approach the problem. Firstly, we are going to explore what happens when economists try to be psychologists, and then we will look at it the other way around.

The bridge is beautifully constructed from both riverbanks.

Sadly, it does not meet in the middle.

ECONOMISTS PLAY AT PSYCHOLOGY

It makes sense to start the debate from the point of view of economists. They are the more motivated players in the debate because if they fail to demonstrate that wealth causes happiness, then their entire discipline is as much use as a chocolate teapot.

So how good are economists at psychology?

The first economist who achieved fame by playing psychology was Richard Easterlin.203 His research gave rise to what became known as the “Easterlin Paradox”. This states that once people have obtained the basics of nutrition and shelter, then increasing their wealth does not make them any happier. The Easterlin Paradox is a very important conclusion, because if it is true, then capitalism has ceased to benefit mankind.

Easterlin’s research is valuable up to a point, but relies on one rather significant flaw: his measurement of happiness. To measure happiness, first we need a unit of measurement. Let’s call it a ‘happitron’. We also need a device to count happitrons. Let’s call it a ‘happitronometer’. Easterlin’s happitronometer consisted of, uh . . . asking people! Unfortunately, this means that he was not measuring happitrons; he was measuring beliefs, and these will be subject to correlated bias according to cultural emotional behavioural manipulations. To his credit, Easterlin recognised this shortcoming. He distinguished between “avowed” or “reported” happiness, and more sophisticated measures that asked respondents to describe what happiness means to them, and then place themselves on a scale of 1 to 10. For the most part, Easterlin relied on a technique developed by an earlier researcher called Cantril, who developed the “self-anchoring striving scale”. However, even this more sophisticated measure relies on the questionnaire respondent calibrating their own happitronometer.

In any case, the only outputs of Easterlin’s respondent-calibrated happitronometers were “very happy”, “fairly happy” or “not very happy”. His happitronometer scale does not go all the way to the bottom. This of course creates an interesting problem in happitronometer calibration: does “completely depressed” count as zero happitrons, or can the scale go negative? This is not a trivial question because it is difficult to know if ‘unhappy’ means simply the absence of happiness, or a completely distinct emotion. In other words, is its apparent oppositeness just a quirk of language?

There are other problems with this research. For example, when you perform these happiness surveys internationally you have to translate the survey questions into other languages. Cantril (whose data Easterlin used) claimed that great care was taken in this translation. But when the research data is self-calibrated by respondents, there is considerable scope for cultural bias.

Despite all these problems, Easterlin was able to draw some persuasive conclusions. One conclusion is that he found that at any point of time within a country that wealth made a significant difference to people’s reported happiness. Pretty much all research seems to come up with this same conclusion. One could conclude that this is a matter of perception, namely that poor people assume that rich people are happier without having a basis for knowing this. Alternatively, seeing people richer than you creates aspirations that you cannot fulfil for economic reasons. This was a phenomenon that Karl Marx recognised about a century earlier.

Another of Easterlin’s conclusions was that comparing international levels of happiness produced no evidence that citizens of wealthy countries were happier than those of somewhat poor ones, although it does appear that they are happier than citizens of countries with extreme poverty. For example, in the data used by Easterlin, Cuba was about as happy as the USA, and Egypt (one of the poorest countries in his survey) was the third happiest. However, as noted before, it is difficult to avoid data distortion: Much of this data came from 1960. At this time, Cuba was in a honeymoon period following its revolution, and Egypt had just kicked out their British colonial masters and seized the Suez Canal; so the political climate in each country could have produced a blip in reported happiness that had nothing to do with wealth.

Perhaps his most interesting conclusion relates to time series of happiness within a country. The most consistent data seemed to come from Japan in the period since the 1950s and the USA since the 1940s. There is also emerging data from China. What this seems to indicate is that, over time, people within a country don’t get any happier despite significant economic growth over the years. This is particularly shocking in the case of Japan: at the start of this data series, Japan was still crawling out of the rubble of the world’s only two nuclear detonations set off in anger; but by the end of the time series, it was one of the richest countries in the world.

Easterlin’s conclusions have recently been challenged204 both with new data and re-examination of the old data. There has been an explosion of international opinion surveys, notably by Gallup. They talk about “life satisfaction” and researchers are all keen to point out that this is not the same as happiness, but most undermine themselves with a hand-wavy definition of “life satisfaction” that includes a host of emotional factors.

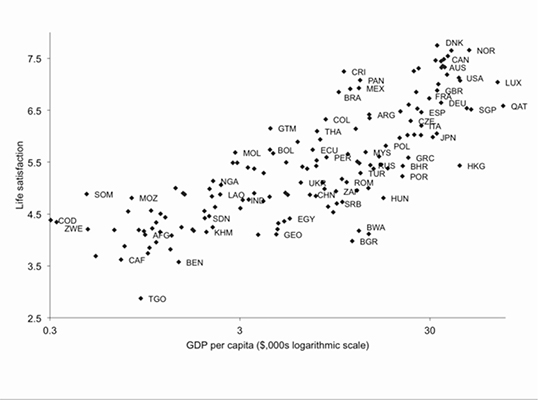

The latest research from Stevenson and Wolfer agrees with Easterlin’s conclusion that relative wealth within a country increases happiness. They also agree with Easterlin that the data from the USA shows that happiness has shown no improvement despite considerable economic growth. However, they challenge Easterlin’s conclusions on Japan because some of the survey questions changed subtly over time, and this causes problems in comparing the data over the time series. I read all this research and I remain convinced of Easterlin’s conclusion regarding the Japanese: their spectacular economic growth has not made them happier. However, Stevenson and Wolfer’s biggest divergence from Easterlin is in their data across countries. Clearly their data, shown in the table below, is much more extensive than Easterlin’s. I have only identified some of the countries, hopefully the more important ones, to avoid the chart becoming too cluttered.

Satisfaction Ladder (Gallup World Poll, 2008–2012)205

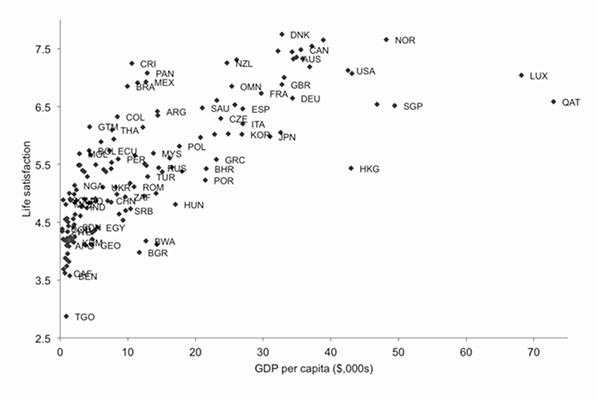

The chart overleaf seems to show a nice relationship between wealth and wellbeing. However, the data scatter is quite wide and the x-axis scale is logarithmic – which is how this data is usually presented. If we remove the logarithmic scale, then an entirely different picture emerges:

Here it can be seen quite clearly that above a GDP per capita in the high-twenty thousands – the level of New Zealand, Czech Republic and South Korea – increasing GDP per capita has no discernable impact on wellbeing, or at least the impact is completely masked by other factors. Stevenson and Wolfers argue that there is no evidence of a satiation point, but they appear to have only statistically analysed it up to a level of $25,000. However, even if you accept that wellbeing is proportional to the logarithm of GDP without a satiation point, then this still supports wealth redistribution because incremental income has a greater wellbeing impact on poorer people.

My suspicion is that this divergence from Easterlin’s conclusion has a simple explanation. It is that the tendency of poorer people within a country to be less happy has gone global. Easterlin’s research was from 1974, but most of his data was much earlier. At that time, poor people (for example in Asia or Africa) had no clue that rich people in other countries had Digital-Microwave-Programmable-Cappuccino-Makers. Today, this knowledge is inescapable because even the poorest people will see TV (even if they don’t own one) and will walk past advertising billboards showing happy people drinking soft-drinks in speedboats. Advertising in less developed countries such as India and China is an incredibly simplistic behavioural deception: a good-looking actor pretending to be happy while consuming a product. It is a relentless and completely unsubtle message. Global media has bought awareness of income disparity to the world’s poor in a way that only existed on a local basis before. Easterlin used 1960s data from (among others) poor people who compared their wealth with the richest person in their neighbourhood. Stevenson and Wolfer use data from the twenty-first century based on people who compare their wealth with people living far away that they see through the media. This difference is therefore affected by the development of media over that period.

Stevenson and Wolfer’s data could even come from people who compare their wealth with people who don’t actually exist – namely actors in American TV shows. It is normal in American TV shows for characters to live a lifestyle that real people with their fictional careers could never afford. For example, the sit-com Friends shows viewers in many poor countries a group of people with mostly mediocre careers who live in New York apartments that would only be affordable to successful professionals. Another example is Sex and the City, where the central character survived on a columnist’s income, but was depicted living in a house in New York’s West Village that recently sold for almost $10 million.206 This is a case of media distortion negatively impacting people’s sense of worth, but it has had almost no media attention. However, it is exactly equivalent to fashion magazines showing thin models and giving all their readers a poor body image. Would poor people be happier if these TV shows depicted the true draughty bedbug squalor that average New Yorkers live with? When I travel in poor countries people react with incredulity when I tell them that there are poor people in America and Europe.

I outlined earlier some of the problems caused by talking to questionnaire respondents who calibrated their own data. There is one other problem that all these researchers share: the scales on their happitronometers only go as low as “Not Very Happy”. What is that? “Not very happy” is how I would describe myself on the days I have root-canal surgery. The data for all this research is just not complete.

Andrew Oswald is a cheery economist whose happitronometer scale goes all the way into the danger-zone.207 His conclusions are closer to Easterlin than to Stevenson and Wolfer. Oswald points out that suicide rates in the USA are the same as they were in 1900, despite six-fold growth in income (although there has been a slight decline in Britain). Oswald also points out that mental health problems, such as depression, are increasing; so is stress at work.

Kate Pickett and Richard Wilkinson picked up this theme in The Spirit Level.208 They demonstrated statistically by using eleven different measures of health and social problems from drug abuse to teenage pregnancy that countries with greater equality perform better. This provoked a stormy debate that split along predictable left/right lines, and as this became more heated the statistical analysis of the protagonists became dodgier and more cherrypicked.

The problem with all this research is that ideology always trumps empirical evidence, and when the evidence contradicts your ideology you reject the evidence. This is because the ideology is a logical tautology that is irrefutable to its believers, but all evidence is subject to interpretation. As with most sociology, the data is sufficiently dirty that it permits statistical creativity: debaters from the left seek out countries that have high inequality and poor wellbeing, and ones from the right seek out countries that are the other way around. This isn’t hard: Japan is a miserable place with extraordinary equality, and in Brazil they never stop partying despite a colossal wealth gap. But there is plenty of evidence that the correlation pointed to by Pickett and Wilkinson is indeed there if you incorporate all the data in a statistically rigorous fashion.

Whether mathematics is politically left- or right-leaning or not leaning at all, all research shows no improvement in happiness in the US over time. Getting richer from one generation to another does not improve the happiness of Americans. There is even research that demonstrates that economic growth negatively impacts human wellbeing.209 This is a vital conclusion because if economic growth has to shrink to avoid environmental collapse there is absolutely no reason why this could not be achieved without people’s perception of their own wellbeing deteriorating.

The view that these factors need to be considered further appears to be growing. All of these ideas are extensively debated in the World Happiness Report210 that debates different measures of happiness and how to achieve them sustainably. Another academic to explore these ideas is Ed Diener of the University of Illinois, who authored an online petition calling for a replacement of economic growth as the arbiter of a nation’s success with measures of wellbeing and ill-being.211 The interesting thing about this is that Diener is a psychologist, but many of his signatories are economists.

PSYCHOLOGISTS PLAY AT ECONOMICS

Let’s revive discussion of Sigmund Freud, the father of psychoanalysis. His theories of the human mind and the treatment of mental illness and his contribution to the understanding of psychology were controversial in his day and remains so in ours. He is best known for his theory of the unconscious mind. [Wait! Haven’t I refuted that already?]

Freud believed that sexual desire was the primary motivator of human beings, and that human personality was formed by childhood experiences. In particular, he believed that we carry into adulthood unconscious desires and fears that have been repressed in childhood.

Freud first published his theories at the beginning of the twentieth century. At this time, his views were in direct opposition to the social views of the time. Contemporary European class structures required respect, and this required the suppression of emotional behaviour. However, it was not long before historical events started to provide new evidence. Freud saw the outbreak of World War I as support for his theories. He argued that this was the release of the primitive unconscious forces that he claimed existed in all humans. World War I demonstrated exactly how he thought we should expect people to behave based on the findings of psychoanalysis.212

World War I bought the seriousness of psychiatric illness to the public’s attention for the first time. The term “shell-shock” had been in use in the military for some time, but it was only after the early offences of the Great War that the term became generally used, including in the medical profession. There had always been psychiatric illness in warfare, but in earlier wars the problem was buried because sufferers were executed for cowardice. World War I was a new kind of war, where men in fixed trenches bombarded one another with heavy artillery. What quickly emerged was that the psychiatric casualties exceeded the physical ones.

Early in the war, the medical profession had little idea how to deal with these mental illnesses. Psychology barely existed at the time, and it wasn’t until the battle of Passchendaele in 1917 that Charles Myers and William Brown started to treat shell-shocked soldiers with hypnosis. Myers’ early efforts concentrated on persuading soldiers under hypnosis that they were not afraid, but Brown realised that the right approach was to take them straight back to their fear. His hypnosis treatment involved encouraging soldiers to relive their experience in its full horror, and thereby release suppressed memories of emotional trauma. It is difficult to be sure that these soldiers were “cured” because the only criteria of the time was that they could return to active duty, but Brown was achieving success rates on this measure of up to 70%.213 These reports of “curing” shell-shock were considered at the time to demonstrate the validity of Freud’s theories.

Freud in his practice in Vienna, and the many psychiatrists and psychologists who developed their knowledge treating the psychiatric casualties of World War I, were only interested in applying these new theories for the mentally ill or emotionally disturbed. However, it wasn’t long before it was realised that these theories could also be used to manipulate the sane. Some of this was motivated by the desire to create better societies. For others, the reason for doing so was profit.

Edward Bernays was born in Vienna, but moved with his family to New York as an infant. Most significantly, Bernays was the double nephew of Sigmund Freud – his parents were Freud’s sister and Freud’s wife’s brother.

Bernays started his career in journalism and went on to become a press agent. From here he launched the career that caused Life Magazine to name him one of the 100 most influential Americans of the twentieth century. Bernays realised that he could combine his uncle’s theories on the unconscious and the newly emerging theories of Gustav LeBon on crowd psychology. The combination of these theories enabled Bernays to develop the business of public relations.214

Bernays’ earliest success was in promoting Diaghilev’s Ballet Russes that toured the USA in 1915. Bernays admitted “I was given a job about which I knew nothing. In fact I was positively uninterested in the dance.”215 At the time, Americans had no interest in ballet. They thought that male dancers were deviants.216 Bernays prepared editorial letters for all the major magazines and newspapers. Already at this early stage of his public relations career, he was showing his subtle ability to manipulate the perceptions of the public: he countered the prejudice towards male dancers with a questionnaire called “are American men ashamed to be graceful?” This too was placed in certain magazines. Bernays persuaded designers to sell clothing based on the costume design of the dancers, and when they arrived at New York docks, he photographed the onlookers and made sure the pictures appeared in the newspapers. The tour of the Ballet Russes was a spectacular success, and their New York performances were sold out before the first show.

Bernays’ knowledge of his uncle’s theories quickly persuaded him to directly consult with psychologists in his public relations business. In the 1920s, public prejudice (and some laws) prevented women smoking in public. George Washington Hill, the president of the American Tobacco Company realised that he was losing half his market, and he asked Bernays to break the taboo against women smoking. Bernays consulted a psychoanalyst called Dr. A A Brill.217 Dr. Brill told Bernays that cigarettes were subconsciously representative of the penis,218 and that he would need to find a way of countering this image that was exclusively male.

Bernays recruited a group of debutants to smuggle packets of cigarettes to a major parade in New York City. At a given signal, the debutants lit their cigarettes right in front of the assembled newspaper reporters. When amazed observers asked what they were doing, the debutants declared that their cigarettes were “torches of freedom”. This was very shortly after women got the vote in America, and this was a gesture of protest for social equality with men. In Freudian psychoanalytic terms, the image gave women their own penises. This publicity stunt appeared in all the papers, and had a lasting effect on the prejudice against women smoking.

Perhaps Bernays’ greatest contribution was to teach corporate America that they should create products that appealed to consumers’ unconscious desires, rather than their needs. This was an era when the mass-production of consumer goods was in its infancy. The idea that you could make consumers want a Digital-Microwave-Programmable-Cappuccino-Maker that they didn’t need was revolutionary.

Bernays set out to create emotional attachment to consumer goods in the minds of consumers. Later, he went further in that he created emotional attachments to the corporations themselves – for example, the Ford Motor Company. Bernays reinvented economic nationalism – he converted it from a matter of government policy and placed it into the hands of consumers.

Paul Mazur, who became a partner of Lehman Brothers in 1927, wrote: “We must shift America from a needs to a desires culture. People must be trained to desire, to want new things, even before the old are entirely consumed. We must shape a new mentality. Man’s desires must overshadow his needs.”219 What Mazur is talking about here is the re-engineering of what happiness is, and he was talking about doing this to fulfil a profit motive.

In 1928, President Herbert Hoover addressed a group of advertisers and public relations people: “You have taken over the job of creating desire and have transformed people into constantly moving happiness machines; machines which have become the key to economic progress.”220 Hoover is perhaps the first President to recognise that America had become a consumerist society. However, what he is talking about is the reversal of the causal link that I discussed in the first half of this chapter: It is not that economic progress causes happiness; rather happiness can be re-engineered to cause economic progress.

Vance Packard’s The Hidden Persuaders describes how the advertising and marketing industry manipulates the masses into obedient shoppers and voters. People become malleable dough, but the objective of this manipulation seems to be lost in the simple maths of who is paying the advertising industry. US children see on average over 40,000 TV commercials per year.221 This equates to approximately 3,000 hours of TV commercials by the time they have finished high school. This is up from about 1,500 hours in 1980.222 Children younger than nine-years old are incapable of distinguishing between fact and the intent to influence in a TV commercial. Commercials essentially portray people acting happy in conjunction with consumption of a product, and young children absorb this uncritically. Adults might be more critical, but the relentlessness of it means that eventually your critical faculties become fatigued.

If we have been persuaded that buying the Digital-Microwave-Programmable-Cappuccino-Maker will make us happier, then what exactly does ‘happiness’ now mean? If it is indeed the case that the human concept of happiness can be re-engineered to suit commercial or political interests, then all the research referred to in the first part of this chapter is meaningless. It relies on questionnaire respondents to report their belief in their own happiness, but ignores the fact that this belief has been systematically manipulated to correlate with consumption. The research is based upon systematically corrupt data.

If someone believes that they are happy, then does that make their happiness a certainty? Put it another way: Can someone believe that they are happy, but be mistaken? If people are being manipulated to believe that happiness is caused by consumption, and their happiness does not increase despite increased consumption, then we should conclude that their true wellbeing has declined.

Vance Packard explores the morality of the persuasive methods used by the advertising and marketing industry. Surprisingly, the people in this industry are very aware of the issue, and have no problem with expressing it openly. Packard notes an article in Printers Ink in which an ad executive from Milwaukee expresses the view that “America was growing great by the systematic creation of dissatisfaction.” The executive talks about how the cosmetic industry expands by deliberately causing women anxiety about their appearance, and he concludes the article by expressing triumphantly “and everybody is happy”.

Packard points out that many people in the industry simply assume that the moral issues can be dealt with simply: manipulating peoples desires increases economic output, and that has to be good. Again, we are dealing with the reversal of the original causal effect: economic growth may cause happiness, but let’s work on the assumption that dissatisfaction causes economic growth – a contradictory logic.

We reduce the problem to a simple disconnect: economists focus on wealth creation, and assume that this makes people happy. The psychologists who have been our focus here manipulate our perception of happiness to create economic growth. Each party to this argument is creating the assumption that the other relies upon. Each assumes that their argument demonstrates benefit to mankind. But combined, they have created a circular argument.

Capitalism is founded on a belief in a wealth-happiness relationship. However, the sole extent to which this relationship exists is that the ideology that creates the wealth also changes the perception of the happiness.

The ideology manufactures the evidence of its own truth.

The thought is irrefutable.

SCENARIO: CERTAIN HAPPINESS

The Man lived in a world that valued hard work and prosperity. Hard work enabled the people in the Man’s world to build beautiful homes for themselves and live in comfort, and successful people lived in communities with other successful people. They wanted to make friends with people who were happy.

The Man worked in an office. He was good at his job. His boss praised him, and he received regular promotions. Every day, he went to work, opened his mail and delegated tasks to the people who reported to him.

The Man had a Wife. She was pretty and cheerful, and she greeted him when he returned from the office. People in the Man’s world valued cheerfulness. They considered it to be polite to be cheerful, so people were cheerful all the time. If you showed any unhappiness, it might upset other people and that would be selfish. Everyone smiled and greeted one another with a wave.

The Man and the Wife were friendly with the neighbours. The Neighbour Husband had a nicer car that the Man, but the Man pretended that it didn’t matter. The Neighbour Wife was slim and elegant in her designer dresses. She mixed cocktails for the Man and the Wife, and they all laughed and acted happy together.

On holy days, the Man and the Wife went to church. The priest would address the congregation and encourage them to give thanks for all their good fortune. He never preached to them about morality, or tried to make them feel guilty about anything. He didn’t need to. His congregation lived happy, simple, affluent lives and everybody was good to one another.

On the way out of church, the Man noticed that the Wife had a handbag that he hadn’t seen before. “That’s funny,” he thought. “I don’t remember her buying that.” The Man wondered sometimes what she did when he was at the office. Anyway, she was always happy, so why did he need to worry about it?

It wasn’t that the Man had any complaints. He had none. His life was pretty much perfect. It was just that lately he had been wondering what it was that made his world such a good place. He was wondering why everybody couldn’t live this way.

That night, the Wife’s favourite TV show was on. The studio audience was laughing, and he watched the Wife as her face lit up with laughter. But he wasn’t laughing. He was watching her. He was thinking that life was wonderful in an abstract way – thinking it, but not feeling it. He needed to explore these thoughts, but the laughter of the studio audience distracted him; so he went out into the garden. He didn’t want to disturb the Wife because that would be inconsiderate, so he slipped out silently. He walked across the grass in his bare feet.

The sun had gone down, and the clouds were fading from blue purple to the slate grey of night. It was beautiful. The Man told himself that it was so beautiful that he did not need to consider again what had driven him out of the house for his nocturnal think. He stood on the lawn and breathed deeply. He stared at the darkening sky in aimless contemplation. He tried to reach for his feelings. He thought that if he relaxed sufficiently, that these feelings would arise naturally.

So still was the night that only one sound caught his ear. It was the sound of muffled sobbing, and it came from the Neighbour’s garden. He crept over to the hedge, and as he came closer it became clear: The Neighbour Wife was crying in their garden. He called her name in a whisper, and the crying stopped abruptly. He called again, but there was silence. He tried to peer through the hedge, but it was too dense. In the Man’s world, people valued privacy. It was rude to pry.

He went to bed with an uncertain frown, but the Wife was bathed in the warm glow of laughter after her TV show. She fell asleep on his arm with a peaceful smile, and the Man stared at the ceiling breathing the fresh scent of her hair until he too drifted off to sleep.

Next morning, as he drove to work, he saw the Neighbour Wife. As she saw him there was a flash of anxiety across her face. She searched his face for any sign that he might have known it was her crying in the garden, but then she suppressed the anxiety. Denial is the best policy; so she smiled and gave him a cheery wave. Better to pretend that I know nothing he thought, so he waved back. “See you at the party tonight” she called. The Man nodded and smiled.

At the office he was irritable. One of his subordinates was suggesting a better way to execute a project than the way he had devised. He felt disconnected from his function. He knew that his productivity was lower than normal. His boss asked him if everything was OK. “I’m fine,” he said.

That night at the party he was with the Wife and the Neighbours. Several other friends from the Man’s world were also there. Everyone was happy and laughing. Everybody had a drink and the food was as delicious as ever. The conversation was frivolous and people told jokes.

Suddenly, the Man said, “Sometimes I wonder what causes happiness.”

“Ha ha!” said the Neighbour Husband. “You think too much.” But the Neighbour Wife scurried off to get another drink, or to speak to someone else who had caught her attention. The Man thought she was avoiding him. And then the Man caught sight of the Wife’s look. She was staring at him with a look of terror and accusation. Her look was tight. She wanted him to see her look but she wanted her look concealed from everybody else. The look appeared to threaten the Man: “Everything is perfect. Don’t mess with it.”

In the Man’s world, everybody acts happy all the time in accordance with a value system that includes consumerism and a work ethic. They do this because otherwise they will be socially excluded. In the Man’s world, the systematic affectation of happiness has caused a belief in a feeling, where the belief is that the feeling is caused by their values.

In the Man’s world, ‘happiness’ means living in a particular way. The causality is reversed: normally living in a particular way would cause happiness, but in this situation, happiness has been redefined to mean the product of living that way.

Like any other belief system, the belief works due to a logic trap. The value system requires people to act happy all the time, so the ability to relate the behaviour to the feeling has disappeared. But if the value system makes people behave happy all the time, then surely it must be working. The rightness of the value system is irrefutable to the people in the Man’s world. Happiness must be good, but in fact it is merely a behavioural construct.

In the Man’s world, it is of course a problem for the individuals that nobody can identify the feeling of happiness. But it is not a problem for society as a whole because the individuals collectively pressure each other to maintain the denial. The Wife’s look of accusation is part of that system of denial. The system of denial works because nobody can see anyone else’s feeling, and any problem that nobody can see is ignored.

The Neighbour Husband is completely unaware that he does not know what happiness feels like. It has never occurred to him that he is missing part of the experience.

The Wife ignores the issue, but is dimly conscious that she is ignoring it. She buries the issue in conformity. It is a contract that she has made with herself – it guarantees both acceptance and happiness (whatever that means). When the Man raises the question of what makes people happy, it terrifies her because it threatens to break her numb equilibrium.

But the Man cannot ignore his inability to experience the feeling because he yearns for it. He believes that he is happy while not being able to identify the feeling. He needs the feeling.

The Neighbour Wife could be undergoing a more extreme version of the Man’s concern. She is living the perfect life but yearning for a feeling that she cannot isolate – a feeling that she needs without being able to determine what causes it. However, she could be experiencing something more complex: maybe she has, through some great perception, seen though the mask of the people in the Man’s world. Maybe she has learned to identify a subtle glitch of human expression that enables her to tell when people are affecting happiness. By this perception she has become aware of true happiness: the feeling; not the belief. Through this observation she has been able to determine that her own happiness is entirely pretended.

The next morning, the Man set his alarm clock especially early. All good resolutions start with getting up early. He had to throw off this doubt. He was worried that if he didn’t put a stop to his doubts, his friends would sense it. Then they would not want to spend time with him. It was just one of his moods, nothing more. He knew it.

The thought crossed his mind that he might lose his job. “Oh that’s ridiculous,” he thought. Maybe he needed to lose some weight, so all he had for breakfast was a single piece of dry toast and a black coffee.

As he set off for work, the Neighbour Husband was in the drive. He wound down the window of the car.

“Wonderful morning!” he called out.

“You bet it is,” said the Neighbour Husband.

“How is the missus?”

“Oh, she’s great,” said the Neighbour Husband. “She is just doing fantastic.”

As he drove to work, the Man thought that he would get his hair cut at lunchtime, and he would go to the gym on the way home. As he parked his car and walked to the office, he could already feel the spring come back into his step. He bounced up the stairs and greeted the security guard.

It felt good to be at his desk early. There was nobody else there, and he instantly felt his productivity get back into gear. He had read all his daily mail before anyone else arrived. The first to arrive was his boss.

“How is it going?” asked his boss.

“Oh it’s great,” he said automatically. “It’s just great.”

This Scenario is essentially the same as the Generic C/D ideology, but reconfigured to make the ideology centred upon consumerism and a work ethic. I have also expanded upon the basic Generic C/D ideology. The four central characters are stuck in a belief feedback loop, but each of them has achieved a different level of understanding of their situation. A logic trap is only a trap until you have a realisation of what it is. Then it can be escaped.