THE MYTH OF THE GHOST IN A COMA

A couple of centuries ago, a bunch of Ghost in the Machine dogmatists got together and decided to put their ghosts to practical use. They reasoned that the world they lived in was divided into the physical world and the mental world. These two worlds were fundamentally different, and Isaac Newton had tied up the physical world with a set of tidy natural laws: a Theory of Everything. What was needed was a science that would tie up the mental world. That science became known as psychology. We now recognise that Newton’s laws weren’t quite the tidy tie-up that we thought they were, and psychologists today are generally not Ghost in the Machine dogmatists. The sciences arising from the dogma of the Ghost in the Machine produced one outstanding figure: Sigmund Freud. He is best known for his theories on the unconscious mind.

Throughout much of the twentieth century, there was a tradition of philosophical scepticism regarding psychology. Gilbert Ryle said he didn’t understand psychology’s programme134; Wittgenstein questioned how exactly psychologists could create any theory when the critical data they wanted to study (mental phenomena) was invisible to them. However, Freud had the aura of a juggernaut of genius and even Ryle and Wittgenstein shied from criticising him for fear of being run over. Wittgenstein is known to have questioned the scientific nature of Freud’s theories, although never in print. In private conversations, Wittgenstein challenged Freud’s idea that anxiety springs from memories of the trauma of birth. He says that such a hypothesis has the appeal of myth in that it is the outcome of something that happened a long time ago.135 Wittgenstein doubted whether it was possible to design an experiment that would actually establish this as a scientific fact. “Freud is constantly claiming to be scientific. But what he gives is speculation – something prior even to the formation of a hypothesis.”136

Within philosophy, Karl Popper has been about the only fierce critic of Freud willing to commit his opinions to print.137 Popper claimed that Freud’s theories are not scientific because they are not refutable. In the words of Popper: “As for Freud’s epic of the Ego, the Super-ego, and the Id, no substantially stronger claim to scientific status can be made for it than for Homer’s collective stories from Olympus. These theories describe some facts, but in the manner of myths. They contain most interesting psychological suggestions, but not in a testable form.”138 Popper, like Wittgenstein, uses the myth analogy.

In my opinion, Freud has a more serious problem, and that is the notion that the unconscious mind can generate acts that are “irrational”. If we can explain causally why someone acted in such-and-such a way, then by definition the behaviour is rational. This means the class of all “irrational acts” is the same as the class of all actions that we cannot explain causally. Therefore, there is no explanatory content in saying that someone did something “because they were irrational”. “Irrationality” is not an explanation of anything, because it is a non-explanation of everything, and this is a misrepresentation. Is it any surprise that such theories are nontestable? I could say “This morning an irrational force made me get out of bed, and then for some irrational reason I ate my breakfast, and finally something deep in my unconscious mind made me floss my teeth.” This is complete hokum, but fully compliant with Freudian thinking. It is a non-explanation comparable to creationism – a theory where everything can be non-explained. If someone tried to argue that it was my conscious mind that made me floss my teeth, exactly how would they prove it?

Freud, like everyone else, had little idea what the conscious mind was. He was working before Gilbert Ryle busted the myth of the Ghost in the Machine. However, since Ryle, surely any Freudian should have noticed that the conceptual problems of the conscious mind become more severe when we consider a mind that is unconscious. Freud was suffering from a solipsistic bias: because he could see his conscious mind through introspection, he thought it novel that part of the mind was unconscious. But the correct way to look at it is the other way around: what is extraordinary is that part of the brain is conscious. Unconsciousness is what we should expect of it.

Today, scientists have rejected Freud’s notion of the Ego, the Super-ego, and the Id. They have also dumped some of his other more outlandish notions, such as his idea of the “Death Instinct”. However, many of them still seem to be stuck in the “Unconscious-Mind-Causes-Irrational-Acts” groove. This is utter twaddle.

Freud’s notion that primitive irrational forces drive us is clearly diametrically opposed to my own view. I argue that humans are completely rational, but that in pursuing their aim of achieving emotional goals, they rationally self-destruct as a result of corrupt concepts of emotion derived from manipulated behaviour. If the “irrational” has no place in my theory; does this mean that the “unconscious mind” also has no place? It isn’t sufficient for me to dismiss Freud’s theories solely because they depend upon a myth about the mind, because Freud’s theories involved other observations.

Freud saw the unconscious mind as a store of socially unacceptable ideas, of traumatic memories and painful emotions. The repressed thoughts were forced out of the conscious mind by “psychological repression”. Neither Freud nor anybody else described this process in simple causal steps. So nobody ever really knew what psychological repression really was. Freud thought that the repressed thoughts and emotions could surface at certain moments as a force to drive irrational acts. At which moments do they surface? What is the causality?

So, without answering the Hard Problem of consciousness, what is the unconscious mind of an entirely rational person? The answer is that the unconscious mind is not a place in a person’s brain, but a void in their ability to form concepts of emotion.

Let us assume that F is the set of all emotional feeling qualia for a hypothetical individual person: let’s call him Sigmund. I could represent this as follows:

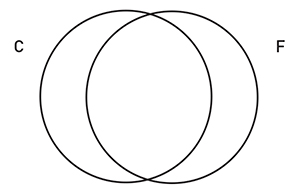

Now let us assume that C is the set of all emotions of which Sigmund has a concept. By this, I mean that he has a belief as to the circumstances that cause the feeling and what behaviour relates to it. I could represent this as follows:

So, what do the three areas represent?

Clearly, normal emotional conception lies in the central area. With idealised normal emotional conception, we experience an emotional quale, and the people in our world experience the same or a similar emotional quale, and nobody fakes or suppresses the behaviour associated with this, so everybody’s experience of this emotional state is represented identically to the outside world through behaviour. It is therefore possible for Sigmund to be able to identify and name the emotional quale underlying the emotion, in himself and in others. He will also be able to study the occurrence of the emotional state in himself and others and learn the circumstances that cause this emotional state. He will therefore have a complete (and correct) concept of this particular emotional state: the circumstances that cause it, the internal experience of the feeling, and the behavioural evidence that accompanies the experience of the emotion in himself and other people. He will also likely have a word for it, which will always be correctly applied.

The area on the left is perhaps the area that is conceptually most difficult to understand. I aim to demonstrate that humans can invent their own emotions, and I call these “virtual emotions”. I will examine this in the next chapter. For now, I will just say that this area represents concepts of emotion where no feeling is present ever, i.e. concepts of emotion that are pure belief.

That leaves the area on the right. For Sigmund, this is the class of all feelings where he has no causal concept of the emotion. This would occur whenever the behaviour is absent. He cannot have an awareness of the feeling in other people, or of what causes the feeling. This is the unconscious mind that Freud and all his followers have misrepresented. Freud is correct that in this space are unacceptable and painful emotions. But “psychological repression” explains nothing without a definition. The feelings for which Sigmund has no concept are in the right-hand section (namely his unconscious mind) because of suppression of the behaviour that they would normally cause. When an emotion is unacceptable or painful, is it not entirely to be expected that he (and other people) would suppress the behaviour associated with it?

Examples of this are the abused woman in Scenario A and the angry man of Scenario B. A Freudian might say that the abused woman acted irrationally because of some force from her unconscious mind. This is not the case; she made an error in identifying a feeling because behavioural suppression meant that she could not complete the concept of the emotion to which it related. A Freudian might say that the man had unconscious anger. Actually, this choice of words makes sense, but it is unconscious because he suppresses the behaviour and therefore has no basis for identifying his own emotion. Unconscious anger is not a thought; there is no such thing as an “unconscious thought”; rather, logically incompatible terms are being married together here without explanation. A thought is something in our phenomenal mind, and there is no sense in saying a thought could meaningfully be anywhere else. Unconscious anger is an absence of concept arising from the absence of the behaviour that permits us to complete the concept.

Freud thought that the unconscious mind also contained “suppressed memories”. Consider the following: imagine a man has a traumatic experience that is completely beyond his prior experience; say a shell-burst in a trench, or some other near-death experience. Such an experience would trigger a feeling that he has never experienced before; something completely overwhelming. His behavioural reaction to this would almost certainly be something that he has never seen before in another human being. His situation is exactly the same as the abused woman in Scenario A. For the abused woman in Scenario A, there is no difference between her being unable to recognise her feeling because everyone in her world suppresses the behaviour, and her being unable to recognise her feeling because nobody in her world ever experienced it. Severe traumatic experience therefore can have parallel characteristics to emotions that reside in the unconscious mind because the behaviour has been suppressed. The inability to recognise the feeling arises through absence of behaviour with which to identify it. The man who experiences the shell-burst has never seen the relationship between the cause of the feeling and its expression in behavioural form in another person. He has an absence of concept.

When biologists discover a weird appendage on a fish, they ask two questions: firstly, what does the weird appendage do; and secondly, how does it boost the chances of survival of the fish? If the biologists can answer these two questions, then they can explain the purpose of the weird appendage in terms of evolution by natural selection. The unconscious mind as conceived by Freud is a weird appendage on a human, and we have to ask the same two questions. Freud thought he had answered the first question. [I disagree!] But nobody asked the second question. We cannot argue that the unconscious mind improves the chances of survival of humans. In fact, it is connected with our tendency to self-destruct. I suspect that Freud would agree with this. How then, does a Freudian justify the existence of the unconscious mind as they construe it?

The unconscious mind did not evolve because it boosted our survival chances; so it must exist for another reason. It is a product of suppressed behaviour – a non-evolutionary explanation. Since we live in a world where words exist for many of these feelings, despite the behaviour having been removed from our perception of it, we have language without concept. When we experience any feeling in this space, any hypothesis as to what caused the feeling is irrefutable because we lack the conceptual framework that would permit refutation. This is not irrational.

What about cognitive neuroscience? Well, it doesn’t really account for the phenomenal mind, so is hardly likely to fair better with a bit of the phenomenal mind that is even stranger. Virtually everything that cognitive neuroscientists know about the functioning of the brain was discovered by looking at unfortunate people who have had parts of their brains destroyed. Neuroscientists then study what normal functions such people have lost and draw their conclusions about which parts of the brain do what function. This process cannot teach us anything about the unconscious mind.

“Oh gosh, Professor Smythers! The patient has become completely rational. The shrapnel must have completely destroyed his unconscious mind.”

“Egad, Doctor Jenkins! I believe you have concluded correctly. We will have to normalise him with misinformation therapy.”

“By Jove, I think you are right, but it’s risky. Misinformation therapy has only ever been tried on people who are partially rational.”

Does this mean that I am replacing Freud’s theory of the unconscious mind with my own theory? No! I don’t have a theory of the unconscious mind; but I am not disputing that the concept has meaning. The difference between Freud’s theory and my nontheory is that Freud saw the unconscious mind as a cause, and I see it as an effect. For Freud, self-destructive actions are caused by the unconscious mind. For me, the unconscious mind is the effect of being unable to perceive the causes of feelings because there is no visible behaviour with which to identify them. Since I see the unconscious mind as an effect, it has little more than a walk-on part in this book. The unconscious mind is not a thing; it is a non-thing – a collection of missing concepts of emotion. It has no physical form, only a logical form.

Freud’s conception of the unconscious mind is identical to the concept of the soul redefined with pseudo-scientific jargon. We were almost rid of the idea of the soul, and Freud took us right back to Square One.