15

The Most Memorable Thing an Astronaut Can Do

Aside from stepping onto the surface of the moon, spacewalking is arguably the most memorable thing that an astronaut can do. Chris Hadfield, Steve MacLean, and Dave Williams were the first Canadians to have performed this remarkable and dangerous feat. The three Mission Specialists were all involved in spacewalks during the construction of the International Space Station. While carrying out their allocated duties there, all of them exhibited more resourcefulness, stamina, and courage than most of us can imagine. They used the skills they possessed, overcame the obstacles they faced, and made significant contributions to the building of the massive structure in the sky. Despite the lonely, hostile, and ultimately unforgiving environment in which they worked, the three never failed in their resolve; never retreated, and in the face of tremendous odds, never left any task undone. Station construction benefited from their expertise.

Chris Hadfield led the way. In 1995, he flew on STS-74. Then six years later, on April 19, 2001, he returned to space on STS-100. Hadfield’s earlier mission was on Atlantis. This time, the spaceship was Endeavour, and the trip would be three days longer than his first. On Atlantis, he had orbited the Earth 129 times; this time he would complete 186 rotations. There were five crewmembers on that first trip; on the second, seven. In both instances, Hadfield was the lead Mission Specialist.

STS-100 blasted off from Kennedy at 2:41 p.m., Florida time, and entered orbit less than nine minutes later. At the same time, the International Space Station was high above the Indian Ocean, and the three crewmembers there were informed of the successful shuttle departure. In fact, about twenty minutes after the launch, they were even able to see a video uplink of the event, provided for them from Mission Control in Houston. The ISS crew had been in place for just over a month, and when the newest shuttle crew docked with them, the visitors from it would be their first.

The STS-100 mission was a special one for all Canadians. Not only was there a fellow countryman involved, but the main purpose of the flight had an important Canadian component. Carefully secured in the big payload bay of the shuttle was the fifty-seven-foot-long robotic invention — Canadarm2. This Canadarm was being transported to, and installed on, the Space Station. Chris Hadfield and American Mission Specialist Scott Parazynski would do the physical work of putting the device in place. With upgrades and the necessary maintenance it would operate from there for the life of the station. From the date of its installation, the arm would become, and remain, one of the most useful and critical components of the entire edifice. No wonder this mission was highly anticipated by NASA, by the Canadian Space Agency, by the thousands of men and women who built the arm, and by those who take an interest in space and in the advances being made there. In essence, the installation of Canadarm2 was a highly complex and utilitarian step into the future.

Not only was the manufacture of the arm a long and intricate construction project; its installation also necessitated thousands of hours of training by the astronauts who were involved in placing it where it was needed. A great deal of that training took place in what most people would regard as a huge swimming pool.

What NASA calls the Sonny Carter Training Facility/Neutral Buoyancy Laboratory was opened near the Johnson Space Center on May 19, 1997. This structure, often referred to simply as “the pool,” was named after astronaut Sonny Carter, who developed many of the spacewalking techniques that ultimately became widely used. The popular and inventive Carter was in training for his second shuttle mission when he was killed in a commercial plane crash on April 5, 1991.

The massive pool, a hundred feet wide and twice as long, is forty feet deep. In NASA-speak, it provides “controlled neutral buoyancy operations to simulate the zero-g or weightless condition which is experienced by the spacecraft and crew during space flight [and] is an essential tool for the design, testing and development of the space station and future NASA programs.”1 In other words, astronauts train in the pool, and by working underwater they learn how to anticipate their roles in space. They “wear their full spacesuits along with weights to keep them underwater. Specially trained personnel in scuba gear are always nearby in case something goes wrong. Inside the pool are full scale replicas of the shuttle payload bay and space station modules.”2

As the shuttle sped towards its linkup with the space station, the Endeavour crew went through the usual stowage of the equipment that was needed during the launch, adjusted to being weightless, and, when possible, took quick glimpses out of the eleven windows of the ship. The payload bay doors were opened en route, and would remain so until it was time to come home. In the bay itself, Canadarm2 was ready for deployment, as was an Italian Space Agency cargo module called Raffaello, which contained several tons of equipment for the space station.

As the journey continued, the Endeavour crewmembers prepared themselves in every way possible for the tasks ahead. To a person, they felt that they were as ready as they ever would be. When asked, Chris Hadfield’s reply pretty much summarized the positive aspects of the moment. “I wasn’t worried at all,” he recalled, “I had trained for four and a half years, and I knew that what I was expected to do would be a tremendous personal, technical, and physical challenge. But no, I wasn’t worried about it.”3 He went on to mention that he and his colleagues were looking forward to reaching the station and fulfilling the expectations of the mission.

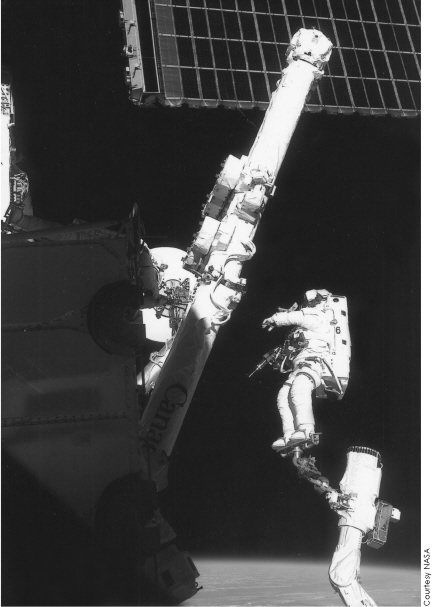

Astronaut Chris Hadfield stands on the end of the Canadian-built Canadarm to work with the Canadarm2 during its installation on the International Space Station, April 2001.

About the same time back home, a newspaper reporter was asking Chris Hadfield’s brother, Dave, about the qualities he had recognized in his astronaut brother. The answer that the writer got reflected the positive elements that Chris would demonstrate in carrying out the duties that awaited him. Obviously, Dave Hadfield was entirely confident in his brother’s abilities, in his quiet professionalism, and in his utter hesitancy to boast about his achievements. “The qualities that make you successful are not those that attract attention,” Dave Hadfield explained. “You need self-discipline, perseverance, and all around intelligence as well as a healthy body. None of these are standouts by themselves.”4

However, taken together, they represented what writer Tom Wolfe determined was “the right stuff.” Indeed, NASA’s reliance on Chris Hadfield in this mission was a vote of confidence in his abilities, and in what he could do.

On the second day of the mission, the flight crew on the shuttle carried out the various rendezvous manoeuvres necessary for a successful linkup to the space station. While that was being done, the spacesuits to be worn by Hadfield and Parazynski while they were outside the orbiter were checked and re-checked, as was the Canadarm, which would be critical for the removal of its namesake and Raffaello from the cargo hold. By 5:00 p.m. on the same day, the Endeavour was some 1,400 miles below and behind the space station, and was gradually closing the gap by 170 miles every time it orbited the Earth. Finally, just before nine o’clock on the morning of Saturday, April 21, the docking occurred. At the time, the two spacecraft were southeast of New Zealand, at an altitude of 243 miles over the southern Pacific Ocean. Then, on Sunday, April 22, 2001, the first spacewalk by a Canadian began. Chris Hadfield floated out of the airlock on Endeavour at 6:45 a.m., CST. Much later, he told me what it was like.

“Because I was the lead spacewalker, I was carrying the burden of responsibility for the entire endeavour. I was completely technically prepared for this walk. I knew right down to the hand motion what I was planning to do for the six or seven hours we were going to be outside. We had back up plans for back up plans.”5

But he was not ready for what came next. “I was not prepared for the overwhelming visual assault that you are subject to when you are outside. You have the entire universe in front of you. It is stupendously visually powerful and stimulating. It is the most beautiful thing you have seen in your whole life. You want to be able to tell people to be quiet and look at this thing. And it is like that all the time! It is mind-numbing to see, and then to try to tear yourself away from this raw, unprecedented beauty all around you and focus on the job you have been training for is physically difficult, and an insult to what is happening all around you. And you have to take some time and soak this thing up because it is so magnificent. It is a rare and tremendous human experience, and you can’t ignore it. I felt I had to take some time and look at it and try to absorb as much as I could so I could make a slight attempt at trying to tell others about it.

“I had to force myself to go back to work. All the while you are outside, the clock is ticking and you are very aware of it. Since everything else but the visual is contained inside your suit, the only real link you have that you are on orbit is the visual.”

But the necessary duties did get done, and Hadfield was extremely cognizant of his role in upholding the Canadian end, in representing his country well in everything he did. This aspect of the mission was further reinforced that morning, shortly before he and Parazynski left the shuttle confines. Steve MacLean sent a message of congratulations to Hadfield, assured him of his support, and wished him all the best. Even Mission Control Houston got into the act by transmitting a rousing version of “O Canada,” performed by Roger Doucet, the beloved police officer who used to sing the national anthem at Montreal Canadiens hockey games. No wonder Hadfield was determined to do his best. The pressure was unrelenting.

Once the magnificent shock of being at one with the universe was somewhat absorbed, the two spacewalkers turned their attention to matters at hand. Their first task was to install an ultra high frequency antenna (UHF) on what was called the Destiny module of the space station. The twenty-eight-foot-long Destiny was an American laboratory that had been affixed to the ISS a couple of months earlier. The deployment of the antenna took two of the seven hours in the first spacewalk. But then, just as the two men were getting more attuned to their surroundings and becoming more confident in their abilities outside the shuttle, Hadfield found himself embroiled in a situation he could never have predicted. In fact, his problem was unprecedented, unexpected, and serious — but not even mentioned in NASA’s official status report that covered the day.

Chris Hadfield suddenly went blind!

What happened was mentioned, rather casually, by Hadfield himself, in answer to my question regarding methods of rescue in case an astronaut became incapacitated during a spacewalk. When I asked the question, I had no idea how close to home it actually was.

“You can become incapacitated for a lot of reasons,” he explained, “so we practice how to deal with whatever the problem is: right from someone being sick and throwing up inside their helmet, to having their vision messed up, to having a hole in their suit, and maybe dying. We practice how we are going to get that person back inside. We practice in a virtual reality lab and go through what we have to do to get the person. You have to get them tethered to you; then you have to move them around in more or less the same way you would move a five hundred pound payload. If they happen to be on the Canadarm, you might be able to fly the arm around to the airlock, so the rescue would be quicker. We train our arm operators to be able to do that. And then the other spacewalker has to stuff them into the airlock. We have to get the hatch closed and get them depressurized. I think we could probably do it in about thirty minutes, but that would be about as quick at it would happen. I was blinded, and I could not see for at least half an hour when I was on my first spacewalk.”

The remark was unexpected.

“I was working away outside,” Chris Hadfield told me, “and suddenly my left eye became irritated. Then it started tearing up and stinging, like when you get raw shampoo in your eye. Your eye shuts and you have to rub it and flush it because you can’t see out of it anymore. Well, my eye started doing that. Because I could not figure out what was causing the problem, I tried to work with one eye for a while, and I didn’t tell anybody. The trouble is, tears need gravity, and drain because of gravity. That way, your eye cleans itself; it generates tears, which wash the contaminant from your eye, and when there is gravity causing the tears to fall, you are okay.

“But without gravity, you just get a bigger and bigger ball of contaminated tear. Then it gets big enough so that it goes across the bridge of your nose and gets into the other eye. That’s what happened to me. Soon both of my eyes were blinded and I couldn’t see out of either of them,” Hadfield explained. As he did so, he paused in his narrative, as if temporarily reliving the experience. His facial expression told me that describing the situation — even long after the fact — was not particularly pleasant.

“I opened and closed my eyes, again and again, but they wouldn’t clear, and the situation actually got worse. Now both were totally clouded with the contaminant. Finally, I called Houston, told them I couldn’t see, and that I would have to take a break.” Meanwhile, Hadfield was well over two hundred miles above the Earth, isolated from his partner, gripping the shuttle, and travelling through space at ten miles a second. Yet, even with the discomfort and the uncertainty of what was happening, he refused to panic, and was able to talk to Mission Control in the same kind of casual matter of fact manner that airline pilots use when they welcome passengers on a flight.

“But Houston was quite worried because our suit gets rid of carbon dioxide by using a chemical called lithium hydroxide, and we get our oxygen through our backpack, and it flows through a lithium hydroxide canister. But if the chemical breaks through its filter and gets into the suit, one of the first symptoms is eye irritation. It’s also bad for your health because it can get into your lungs and do a lot of damage.

“So Houston’s concern was that I had a lithium hydroxide leak. Because of that, while I was still blind, they asked me to start venting my suit. So I opened the valve for this, and started dumping my oxygen. I remember thinking: this is a really strange place to be. I can’t see what I’m doing; I’m holding onto a spaceship, and I’m pouring my life-giving oxygen out into the vacuum of space. But I became very philosophical about it, hoping it would clear the problem after a while. But it didn’t.

“So, after about fifteen minutes of that, Houston said: ‘Okay, close the valve.’ So I closed the valve. But after twenty-five to thirty minutes, I’d cried enough, and there was enough tearing that it diluted the contaminant. Then the tears evaporated. So, taking the place of gravity, the evaporation took place and I could see again, though things were a bit murky at first. They got better though, and I was able to see for the rest of the spacewalk.

“When I came inside, they took a bunch of swab samples of the dried stuff that was around my eyes, and we found out what it was. We had covered the inside of the visor with a surfactant to keep it from fogging up, and the surfactant had a few chemicals in it. I had a water leak from my drink bag, and it had picked up a big bubble of this stuff and that got into my eye. It was nothing life-threatening, but it was mission-threatening. Since then, we have changed the way we clean our visors.”6

While all of this was happening in space, the media on Earth were generally not aware of just how serious Chris Hadfield’s problem was, although they noted it in passing. For the most part, the stories they ran dealt with the size of Canadarm2, the fact that it was essentially a “high tech crane,” that it weighed more than a ton and a half, and that it was made of aluminum, steel, and graphite epoxy. The fact that it was folded up in the cargo bay of the shuttle was mentioned, and that Chris Hadfield had once described it as a big spider with its legs curled up. Once unfolded and attached to the space station, the arm would represent a “giant leap for Canada.”

Now that he could see again, Hadfield turned to his partner, and together they began the transfer of the arm to its placement on Destiny. Shuttle Pilot Jeff Ashby used the robotic arm on-board to lift the big metal, U-shaped pallet that held Canadarm2 out of Endeavour’s cargo bay. Then the two spacewalkers attached the pallet to Destiny, and hooked up temporary power cables so that the “space crane” could be activated and its arms unfolded. While all this was being done, Chris Hadfield was tethered to Canadarm by foot restraints so that he would not float away into space, and so that his hands were free to perform the operations needed.

From time to time during the procedure, Hadfield mentioned the stark, utterly majestic beauty of the world in which he worked. He had emerged from the shuttle when it was over the Atlantic, just off the coast of Brazil, and his first observations were exuberant, like the delight of a child in thrall of what is before him.“Oh man, what a view!” he exclaimed as he exited the airlock for the first time. “That takes your breath away.” Later on, he tried to describe the Australian southern lights for his colleagues inside the shuttle and at Mission Control: “The horizon is lit up with tentacles going up a huge distance into space,” he said. “They come almost far enough to be under us.” Then at one point, he reflected on the whole experience when he said to Scott Parazynski: “When I was a little kid wanting to grow up to be an astronaut, this is what I wanted to do.”7

By the end of that first day, he and Parazynski had spent seven hours and ten minutes spacewalking, and during that time had circled the Earth almost five times. More importantly, they had completed the objectives for the day, and each had earned a much-needed rest. However, their excitement made resting difficult.

The work the spacewalkers did was noted elsewhere, of course. On their farm at Milton, Ontario, Roger and Eleanor, Chris Hadfield’s parents, watched the unfolding of the drama on NASA TV. They were transfixed in front of the flickering screen, and found themselves listening intently for the always clipped and sometimes garbled transmission of their son’s words from space. Both were so proud of him, and at times found it difficult to comprehend the wonder of what was happening so far above the clouds.

Senior astronaut Marc Garneau followed the progress of the walk from his location at the Canadian Space Agency facility, near Montreal. The veteran flier told a reporter that he felt two things as he watched his colleague and friend conduct an activity that he himself had not been fortunate enough to have done.

“The first is, boy, I wish I was doing that,” he said. “The second is a lot of pride. Chris is fulfilling a dream, and at the same time helping Canada to do something extremely important for us. We have reached a level of maturity comparable to other space nations.”8

In Houston, Mission Control was ecstatic with the success of the whole operation. When Hadfield and Parazynski ventured outside the shuttle for the second walk, the status report issued by NASA referred to the fact that Endeavour’s two spacewalkers worked as space age electricians, completing connections that allowed the new International Space Station robotic arm to operate from a base on the outside of the Destiny science lab.

“Hadfield and Parazynski worked to complete all of the primary goals of the mission, including the connection of the Power and Grapple Fixture circuits for the new arm on Destiny, the removal of an early communications antenna and the transfer of a spare Direct Current Switching Unit from the shuttle’s payload bay to an equipment storage rack on the outside of Destiny.”9 In those few words, despite their jargon-like tone, it is obvious that the decision makers in Houston were pleased.

The second spacewalk lasted seven hours and forty minutes, and as far as the two men outside were concerned, went extremely well. By the end of their work day they were able to reflect on what had transpired, take pride in it, and see the results of their efforts. Canadarm2 was in place, was operational, and ready, at long last, to make the further expansion of the space station a reality.

Another historic part of the mission for Canada occurred on Saturday afternoon, April 28, when an astronaut on the space station named Susan Helms, who was part of what NASA called Expedition Two, used Canadarm2 for the purpose for which it was intended. The maneuver was described in a status report from Mission Control issued that day: “A Canadian ‘handshake’ in space occurred at 4:02 p.m. Central time today, as the Canadian-built space station robotic arm — operated by Expedition Two crew member Susan Helms — transferred its launch cradle over to Endeavour’s robotic arm, with Canadian Space Agency astronaut Chris Hadfield at the controls. The exchange of the pallet from station arm to shuttle arm marked the first-ever robotic-to-robotic transfer in space. The successful exchange of the pallet was the last remaining major objective of the mission.”10

While the shuttle was docked at the ISS, the crews of the two spaceships had a reunion of sorts, and everyone not otherwise occupied pitched in and unloaded the over four tons of supplies that were delivered in the Raffaello module. These included racks of hardware intended for installation on Destiny, running slats for a broken treadmill, radiation shields, mufflers for noisy machinery, science equipment, and even clothes and towels. As well, “the shuttle astronauts delivered mail from home, apples, oranges, carrots, celery and candy.”11 In return, Raffaello would be packed with gear and garbage from the station, all of which would end up in recycling depots or dumps once returned to Earth. None of it was jettisoned into space.

The crew of STS-100 returned to Earth on schedule, but they were unable to land at Cape Canaveral as hoped. Cloud, continuous rain, and high winds swept the Atlantic coastal areas of Florida on May 1, the date of return. As conditions were expected to remain unchanged for the days that followed, Kennedy Space Center’s Leroy Cain, the entry flight director, waved off landing opportunities there. Instead, Endeavour glided to an 11:11 CDT touchdown at Edwards Air Force Base in California. The mission was over. In all respects, it had been successful, historical, and safe.