Initially German tactics during the long withdrawal still emphasised the need for counter-attack as soon as an enemy attack took place. However, many officers soon came to realise that these counter-attacks involved great human cost which was depleting the army, for which fewer and fewer replacements were available. For this reason the fighting retreat was modified so that when the enemy attacked, German troops would withdraw to a rearward prepared defensive position as soon as the first position was in danger of being destroyed. The Germans continued to attack to recover important lost ground, but as the war went on German forces became starved of men – both experienced and replacement troops – and attacks were frequently less forcefully carried out than during the advances of the first two years on the eastern front.

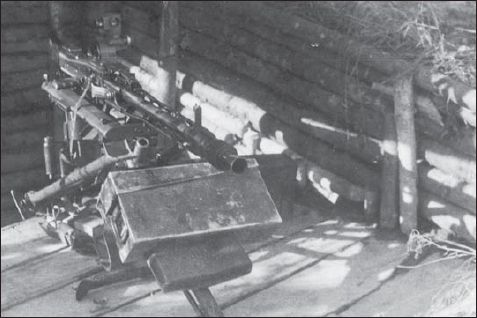

A typical prepared battalion defensive position would locate all infantry units behind frontal minefields. Battalion mortars and any short-range infantry guns supported the infantry positions and anti-tank weapons were placed about 1,000m (3,280ft) to the rear, where they were able to shoot enemy tanks but were not immediately vulnerable to attack. Lanes through the minefields allowed patrols and wire-maintenance parties to operate safely. The rapidity of Russian advances made such positions luxuries, however, and the Germans were often unable to form stop lines except at natural obstacles, particularly rivers. The Russians had learned their basic tactics from the earlier German successes, and with ever-increasing manpower available, plus numerically superior armour and artillery, were now able to give the Germans their lesson back.

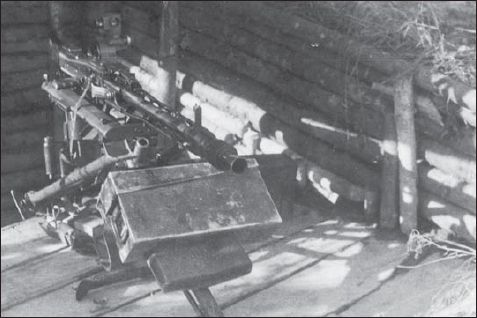

A good view of an MG42 on its tripod, set up for fixed-line firing at night. The ammunition box resting on the back pad in front of the gun is to improve stability, as the gun was prone to vibrate heavily.

A prepared battalion defensive position, showing its considerable minefield protection.

Defensive positions were arranged in depth, with the strength concentrated where the main enemy attack would take place. Advanced and outpost positions were put out from around 6,500m (21,300ft) in front of the main fighting line (Hauptkampflinie). The Germans aimed to stop the enemy as far out as possible, or to direct his attack towards points of their own choosing. Artillery fire always covered the advanced and outpost positions.

From late 1943 onwards, German defence became more passive, as the Wehrmacht began to lack the mobility and reserves they had had previously. The Waffen-SS was kept up to strength whenever possible, but many infantry battalions and regiments were always short of men – both the older, experienced men, and new replacements for the dead, wounded and captured, whose numbers mounted alarmingly.

Protected by the outpost and advanced positions, the main defence line was, if possible, constructed to give individual strongpoints linked to provide a belt. The strongpoints were built to give all-round defence, and surrounded by wire and minefields. Heavy weapon support consisted of machine guns, mortars and, when possible, infantry guns and anti-tank weapons. The new Panzerfaust was invaluable for giving the German infantryman close-range anti-tank capability.

Another section position, well dug in with overhead cover, this time of thick concrete blocks.

The Germans sited their main defence positions on reverse slopes wherever possible, avoiding detection by the enemy and making the positions more difficult to observe by artillery spotters. If there was time, woods were fortified, but the speed of the Russian advance often made such luxuries impossible. The narrower rivers and streams were defended on the enemy side, and the waterway used as an anti-tank ditch. Wider rivers were defended on both sides where there was a crossing point to allow withdrawal of German troops as the enemy attack developed.

In the face of the growing number of Russian tanks, the German soldiers created obstacles to funnel the enemy into lanes protected by anti-tank guns and on to minefields. The main anti-tank ditches were sited between the front-line trenches and the anti-tank gun positions, allowing tanks to penetrate the front-line, only to be destroyed by the anti-tank defences. Infantry accompanying the tanks were destroyed by the machine guns and rifles of the front-line defenders, and by artillery support from the rear. Minefields were concentrated within the defensive positions in the front-line, with only a few scattered mines to the front of those positions. Experience had taught the Germans that Russian artillery fire could easily create safe lanes through minefields.

Towns and villages were regarded as excellent strongpoints by the Germans, especially where the buildings were built of stone or good brick. Towns offered especially good anti-tank defences, due to the problems of coordinating attacks in built-up areas and the ease with which tanks could be attacked at close quarters, especially with the Panzerfaust. The edges of the built-up area were lightly defended; the main resistance was concentrated further in. This made artillery support for an attack more difficult to observe and control, and meant that the attackers would be funnelled along roads to points the Germans chose to defend.

As the enemy penetrated further in, pockets of Germans would create small centres of resistance to slow down the rate of advance, and provide flanking fire on the attackers. Every attempt was made to trap the attacker in culs-de-sac, and to attack with a mobile German reserve held within the built-up area for that purpose. Larger reserves were held outside the town.

The German soldier had, by 1944, learnt the skills of urban combat. Booby traps were laid in both defended and unoccupied buildings; doors were blocked and windows filled with sand bags or bricks; ‘mouseholes’ were established in rows of houses so that the Germans could move internally, away from enemy fire and observation. Firing took place from the centre of rooms, not from the windows, so that muzzle flashes were well concealed from the enemy outside; after firing the Germans frequently moved to another room or even another storey of the building they were defending. Even the cellars were defended, with the lessons learned in Stalingrad being part of German doctrine thereafter.

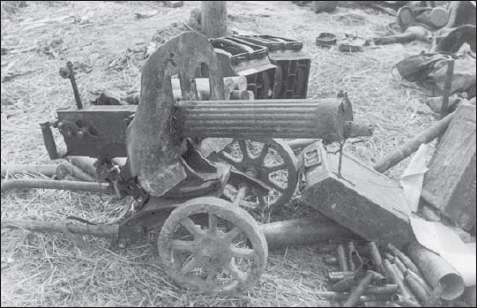

A captured Russian Maxim water-cooled machine gun. The weapon was far too heavy and awkward to handle for the Germans to be interested in using it, especially in comparison with the MG42.

Villages were defended as an entity: the village (if large) would have an inner defensive position surrounded by the outer defensive positions. The same aim was apparent: funnel the enemy into the killing zone in the centre, and harass his advance whilst he was moving through the outskirts. Tanks were regarded as ineffective in built-up areas, but when they were destroyed the Germans made sure that they could not be used by the Russians as observation posts or rendezvous points.

Although the Germans had spent the first two years of the campaign in Russia advancing, they had an effective system for withdrawal. The German troops would withdraw if there was no prospect of success in the battle, and particularly if they were in imminent danger of defeat. Careful planning was needed to break off an engagement, and to retire to rearward defensive positions. The Germans were adept at withdrawing troops securely, with all units completing a phased, planned withdrawal to the surprise of the enemy.

However, the German retreat on the eastern front was often the result of far superior numbers of Russians attacking; furthermore the Russians developed their own form of the war of movement, and were very successful in pushing the Germans back. Russian guns, tanks and infantry worked together extremely efficiently, with the tanks penetrating the German line and flooding towards the rear areas; following them were the infantry, who mopped-up German defences as they were met (or merely bypassed them). The attack was always supported by ever-increasing artillery firepower, from the outset to the limit of the tank advance and beyond. The Germans were understandably respectful of the Russian artillery, which made their lives hell, as one German soldier who fought at Kursk recounted: ‘first came a dreadful barrage. I knew in advance what it was going to be like, because my father, who had been injured at Verdun in the First World War, described it to me. He knew what it was like to be at the mercy of the big guns – and in 1943 the Russians had many big guns. My father said that he had had to jump into shell holes. The ground looked as if it had been ploughed up. It was the same for us in Russia. You saw on the left or the right of you that there was a new shell crater, so you jumped into that one and then the next one. This went on for three hours before the actual fighting began.’

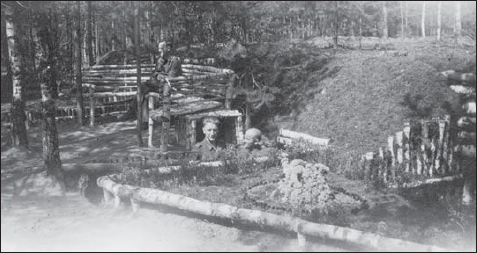

This rest area is the result of homesickness, with its wooden bank of seats and the flowers in the foreground. However, it has a military purpose as well, for beneath the bench is the entrance to the covered bunker on the right of the picture. Unfortunately nothing is known of the purpose of the bunker, but it may well be a headquarters.

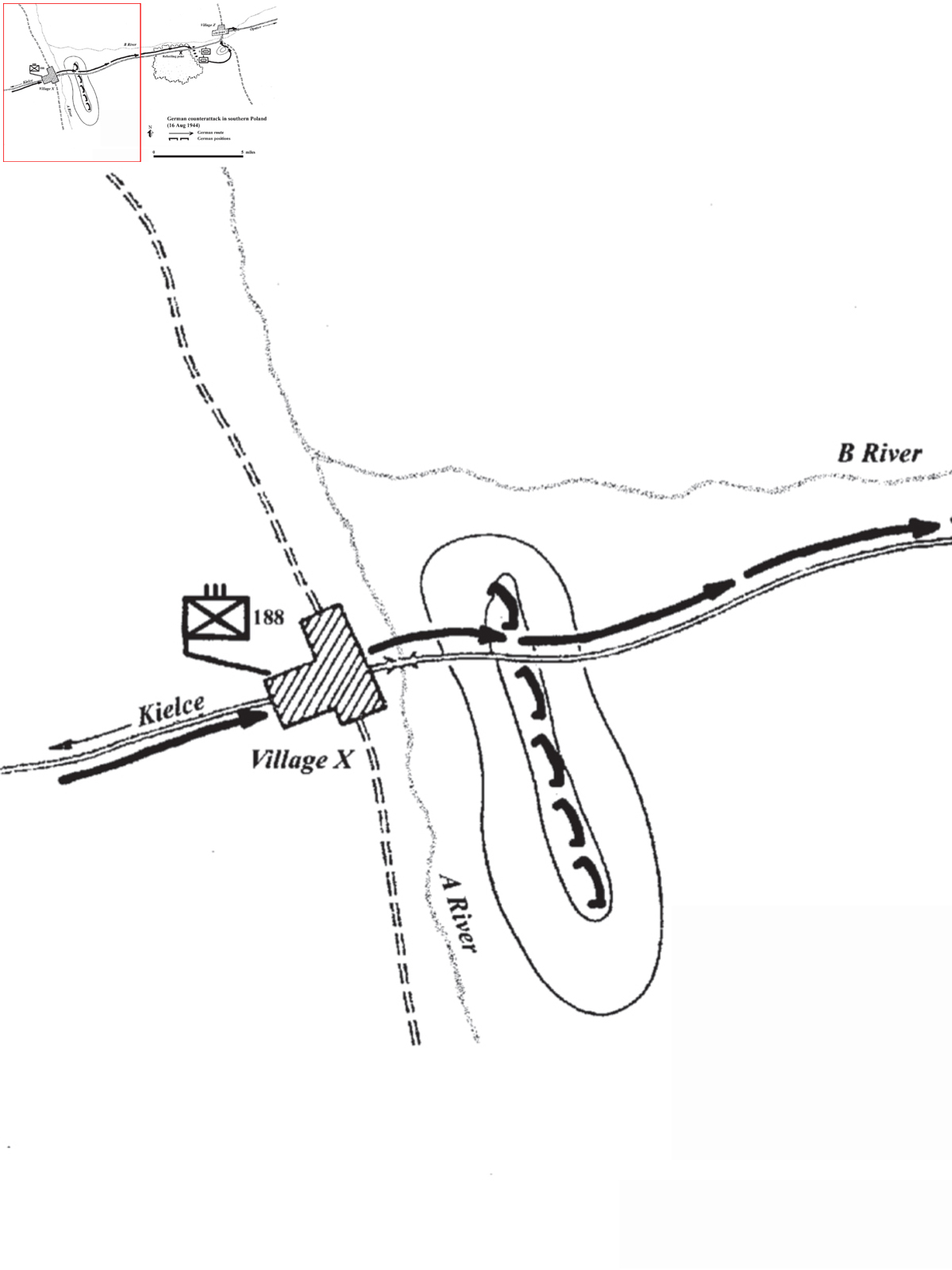

The Germans became aware quite soon during the war in the east that tank-infantry cooperation was vital to any success, and in those isolated instances in which German armoured forces units were at full strength, they were still able to attain local successes, even in the summer of 1944. During the nights of 13 and 14 August 1944, the infantrymen of 3 Panzer Division detrained at Kielce in southern Poland. Their mission was to stop the advance of Russian forces that had broken through the German lines during the collapse of Army Group Centre and to assist the withdrawing German formations in building up a new defence line near the upper Vistula.

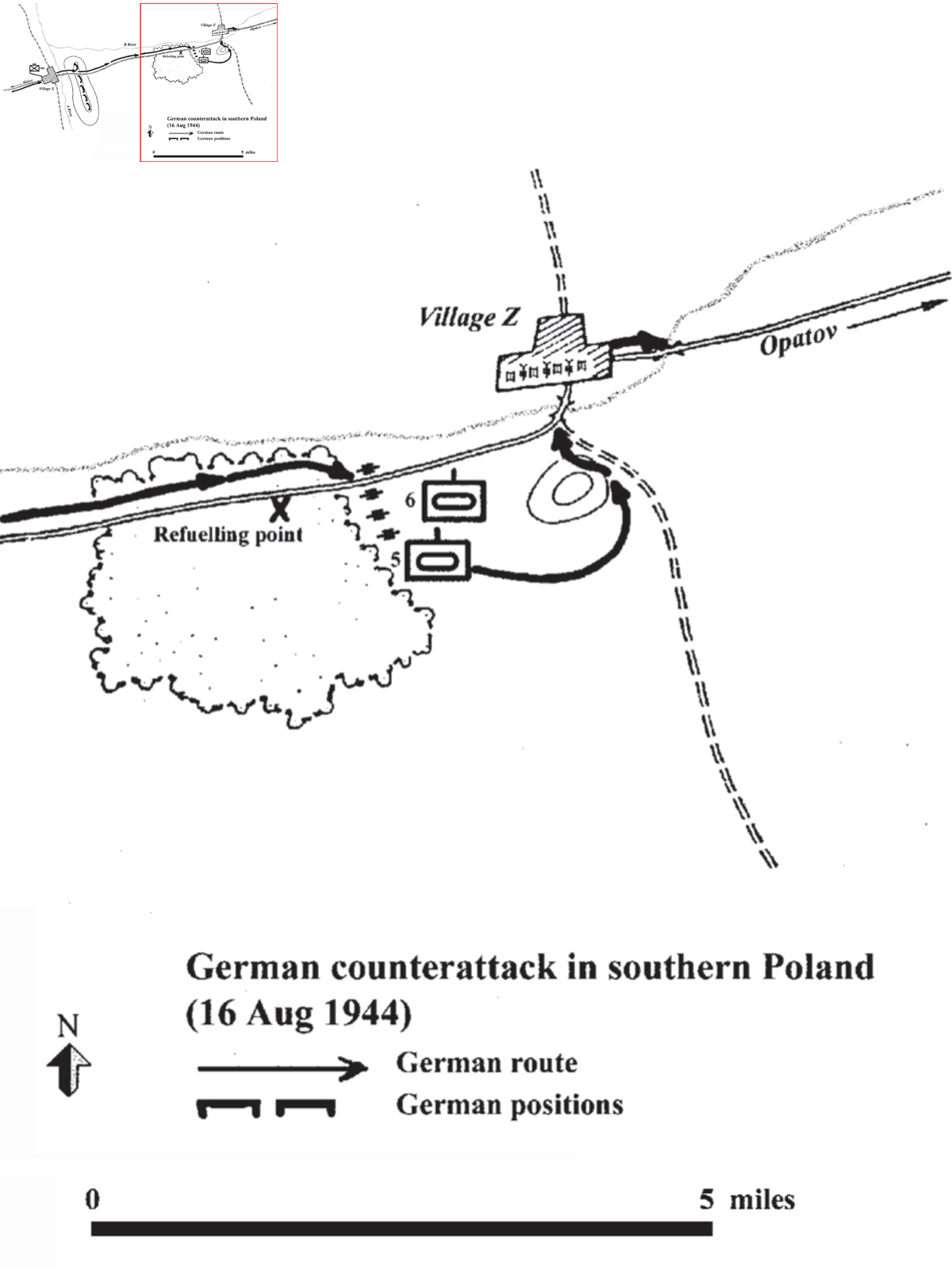

In order to allow all units of the division the time needed to prepare for their next commitment, and at the same time secure the route of advance, the division commander decided to form an armoured forces task force from the units that had detrained first. The force was to be led by the commander of II Tank Battalion and was to consist of 5 and 6 Tank Companies, equipped with Panther tanks, one armoured infantry company mounted in armoured personnel carriers, and one artillery battery equipped with self-propelled 105mm howitzers. The task force was to launch a surprise attack on Village Z, situated approximately 48km (30 miles) east of Kielce, and seize the bridges south and east of the village in order to permit the main body of the division to advance along the Kielce–Opatow road toward the Vistula.

The attack was to be launched at dawn on 16 August. According to air reconnaissance information obtained at 1800 on 15 August, Village Z was held by relatively weak Russian forces and no major troop movements were observed in the area. The only German unit stationed in the area between Kielce and Village Z was 188 Infantry Regiment, which occupied the high ground east of River A and whose HQ was in Village X.

A knocked out T34 tank. The vehicle has been hit on the far side and subsequently ‘brewed up’, as the deposits in front of the turret show. The T34 tank turned the fortunes of the Russians around, and was highly mobile and very effective against the German Mk III and Mk IV tanks.

The country was hilly. Fields planted with grain, potatoes and root crops were interspersed with patches of forest. The weather was sunny and dry, with high daytime temperatures and cool moonlit nights. The hours of sunrise and sunset were 0445 and 1930, respectively.

The task force commander received his orders at 2000 on 15 August and immediately began to study the plan of attack. Since the units that were to participate in the operation had not yet been alerted, the entire task force could not possibly be ready to move out before 2300. The maximum speed at which his force could drive over a dusty dirt road without headlights was 10km/h (6mph). The approach march to Village Z would therefore require a minimum of five hours. Taking into account the time needed for refuelling and deploying his units, the commander arrived at the conclusion that the attack could not be launched before dawn. Since the operation might thus be deprived of the element of surprise, he decided to employ an advance guard that was to move out one hour earlier than the bulk of his force, reach Village X by 0200 at the latest, and cover the remaining 15km (9 miles) in 1 ½ hours. After a short halt the advance guard could launch the attack on Village Z just before dawn.

At 2020 the task force commander assembled the commanders of the participating units at his HQ and issued the following verbal orders:

6 Company, 6 Tank Regiment, reinforced by one platoon of armoured infantry, will form an advance guard that will be ready to move out at 2200 in order to seize Village Z and the two bridges across River B by a coup de main. A reconnaissance detachment will guide the advance guard to Village X. Two trucks loaded with fuel will be taken along for refuelling, which is scheduled to take place in the woods two miles west of Village Z.

The main body of the task force will follow the advance guard at 2300 and form a march column in the following order:

2 Tank Battalion Headquarters,

5 Company of 6 Tank Regiment,

A Battery of 75 Artillery Regiment, and 1 Company of the 3 Armoured Infantry Regiment (less one platoon).

After crossing River A, the tank company will take the lead, followed by battalion headquarters, the armoured infantry company, and the artillery battery in that order.

The task force will halt and refuel in the woods two miles west of Village Z. Radio silence will be lifted after River A has been crossed.

The commander of 6 Company will leave at 2100 and accompany me to the HQ of 188 Infantry Regiment and establish contact with that unit. 5 Company’s commander will take charge of the march column from Kielce to Village X.

Upon receiving these instructions the commander of 6 Company, Lieutenant Zobel, returned to his unit, assembled the platoon leaders, the company sergeant major, and the maintenance section commander and briefed them. He indicated the march route, which they entered on their maps. For the march from Kielce to Village X, the headquarters section was to drive at the head of the column, followed by the four tank platoons, the armoured forces infantry platoon, the fuel trucks, and the rations and maintenance sections. The senior platoon commander was to be in charge of the column until Zobel joined it in Village X. Hot coffee was to be served half an hour before the time of departure, which was scheduled for 2200. The reconnaissance detachment was to move out at 2130 and post guides along the road to Village X.

A corduroy road made of small tree trunks, absolutely vital in keeping transport moving to and from the front. The detail in this photograph shows a road junction and a horse-drawn trailer, suitably camouflaged in the wider passing place on the right.

After issuing these instructions to his subordinates, Zobel rejoined the task force commander, with whom he drove to Village X. When they arrived at the HQ of 188 Infantry Regiment, they were given detailed information on the situation. They learned that, after heavy fighting in the Opatow region, the regiment had withdrawn to its present positions during the night of 14–15 August. Attempts to establish a continuous line in conjunction with other units withdrawing westward from the upper Vistula were under way. The Russians had so far not advanced beyond Village Z. Two Polish civilians who had been seized in the woods west of the village had stated that no Russians were to be seen in that forest.

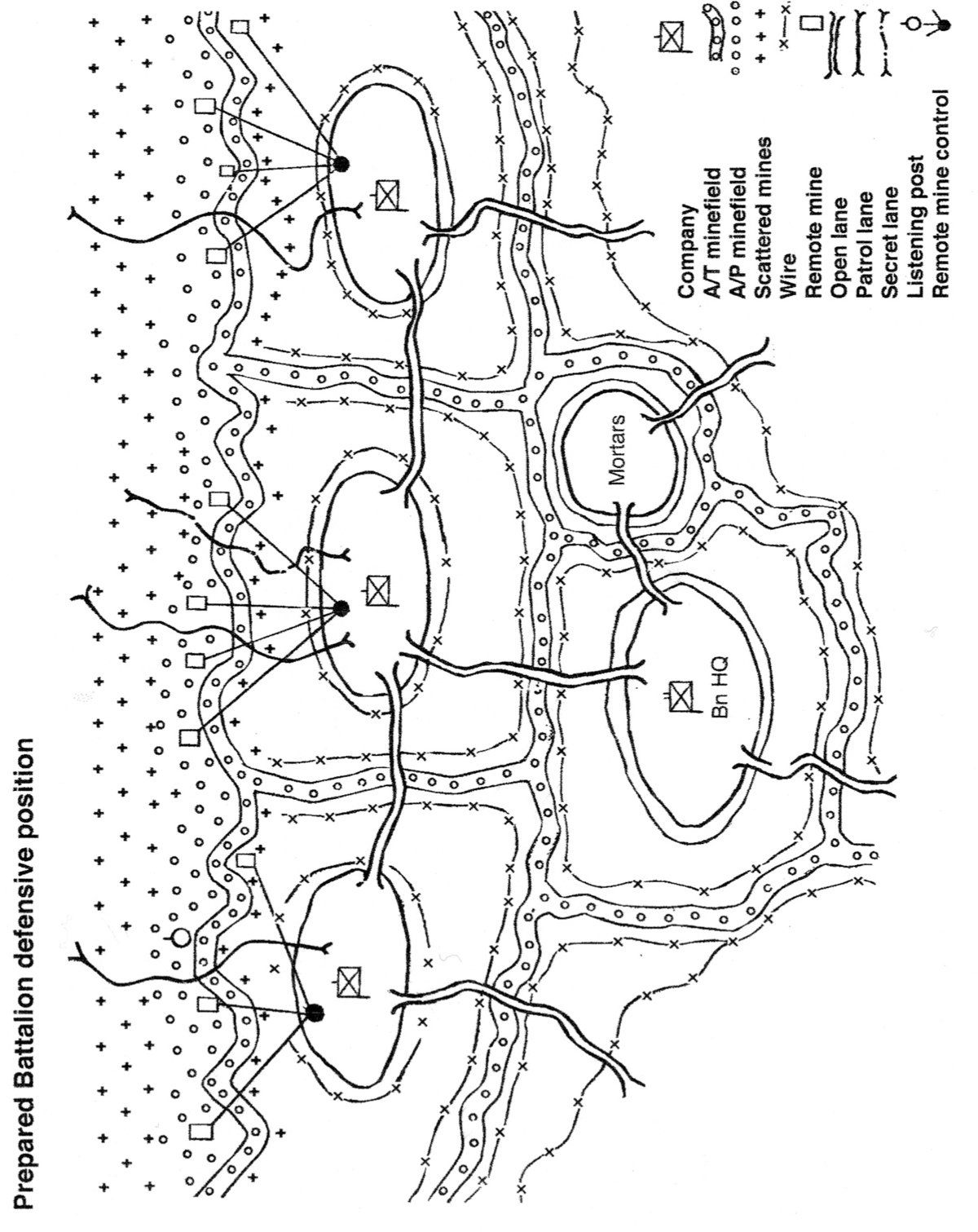

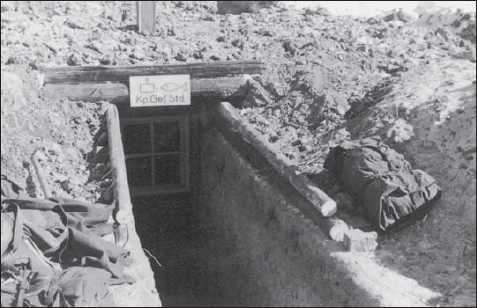

The entrance to a company battle headquarters. From this position the company commander could control his men and be protected from shell and bomb. The unit is 2 Company of 34 Fusilier Regiment, which was part of 35 Infantry Division. The unit was retreating towards Danzig when this photograph was taken.

German counter-attack in southern Poland.

The task force commander thereupon ordered Zobel to carry out the plan of attack as instructed. Zobel awaited the arrival of the advance guard at the western outskirts of Village X. When the column pulled in at 0145, Zobel assumed command and reformed the march column with 1 Tank Platoon in the lead, followed by the headquarters section, 2 and 3 Tank Platoons, the armoured infantry platoon, the wheeled elements, and 4 Tank Platoon.

A guide from 188 Infantry Regiment rode on the lead tank of 1 Platoon until it reached the outpost area beyond River A. The column arrived at the German outpost at 0230. The sentry reported that he had not observed any Russian movements during the night. Zobel radioed the task force commander that he was going into action.

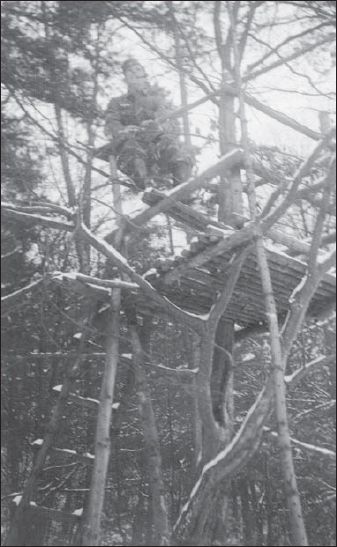

A treetop observation post. These positions were used frequently to enable long-range observation of the enemy, and were very valuable as long as they were well concealed.

To permit better observation, the tanks drove with open hatches. The tank commanders stood erect with their heads emerging from the cupolas, listening with a headset. The other tank hatches were buttoned up. Gunners and loaders stood by to open fire at a moment’s notice. In anticipation of an encounter with Russian tanks the guns were loaded with armour-piercing shells.

At 0845 the advance guard reached the wooded area in which it was to halt and refuel. The tanks formed two rows, one on each side of the road, while armoured forces infantrymen provided security to the east and west of the halted column. Sentries were posted at 50m (164ft) intervals in the forest north and south of the road. Trucks loaded with fuel cans drove along the road between the two rows of tanks, stopping at each pair of tanks to unload the full cans and picking up the empties on their return trip. The loaders helped the drivers to refuel and check their vehicles. The gunners checked their weapons, while each radio operator made coffee for his tank crew. Zobel gave the platoon commanders and tank commanders a last briefing and asked one of the returning lorry drivers to carry a message on the progress of the operation to the task force commander in Village X.

According to Zobel’s plan of assault, the advance guard was to emerge from the woods in two columns. The one on the left was to consist of 1 Tank Platoon, the headquarters section, and 4 Tank Platoon, whereas the right column was to be composed of 2 and 3 Tank Platoons and the armoured infantry platoon. The plan was for 1 Platoon to take up positions opposite the southern edge of Village Z, with 2 Platoon at the foot of the hill to the south of it. Under the protection of these two platoons 3 and 4 Platoons were to seize the south bridge in conjunction with the armoured infantry platoon, drive through the village, and capture the second bridge located about half a mile east of the village. Then 2 Platoon was to follow across the south bridge, drive through the village, and block the road leading northward, while 1 Platoon was to follow and secure the south bridge. The tanks were not to open fire until they encountered enemy resistance.

Zobel did not send out any reconnaissance patrols because he did not want to attract the attention of the Russians. In drawing up his plan Zobel kept in mind that the success of the operation would depend on proper timing and on the skill and resourcefulness of his platoon commanders. Because of the swiftness with which the raid was to take place, he would have little opportunity to influence the course of events once the attack was under way.

Here soldiers are preparing the defences of a village during the long retreat. Morale is still relatively good, as can be seen from the smile on the face of the man on the left. The small wooden causeway bridge is of interest.

At 0430, when the first tanks moved out of the woods, it was almost daylight and the visibility was approximately 1,000m (3,300ft). As 1 and 2 Platoons were driving down the road toward Village Z, they were suddenly fired on from the flank by Russian tanks and anti-tank guns. Three German tanks were immediately disabled, one of them catching fire. Zobel ordered the two platoons to withdraw.

Since the element of surprise no longer existed and the advance guard had lost three of its tanks, Zobel abandoned his plan of attack and decided to await the arrival of the main body of the task force. He reported the failure of the operation by radio, and at 0515 his units were joined by the main force. After Zobel had made a report in person, the task force commander decided to attack Village Z before the Russian garrison could receive reinforcements. This time the attack was to be launched from the south under the protection of artillery fire.

The plan called for Zobel’s company to conduct a feint attack along the same route it had previously taken and to fire on targets of opportunity across the river. Meanwhile 5 Company and the armoured infantry company were to drive southward, skirt the hill, and approach Village Z from the south. While 3 and 4 Platoons of 5 Company, the armoured infantry company and 6 Company were to concentrate their fire on the southern edge of the village, 1 and 2 Platoons of 2 Company were to attack across the south bridge, drive into the village, turn east at the market square and capture the east bridge. As soon as the first two platoons had driven across the bridge, the other tanks of 5 Company were to close up and push on to the northern edge of the village. The armoured infantry vehicles were to follow across the south bridge and support 1 and 2 Platoons in their efforts to seize the east bridge. The soldiers of 6 Company were to annihilate any Russian forces that might continue to offer resistance at the southern edge of the village. The artillery battery was to go into position at the edge of the woods and support the tanks.

No more than two tank platoons could be employed for the initial attack because the south bridge could support only one tank at a time. All the remaining firepower of the task force would be needed to lay down a curtain of fire along the entire southern edge of the village. This was the most effective means of neutralising the enemy defence during the critical period when the two tank platoons were driving toward the bridge. To facilitate the approach of the tanks to the bridge, the artillery battery was to lay down a smoke screen south of the village along the river line. Having entered the village, the two lead platoons were not to let themselves be diverted from their objective, the east bridge. The elimination of enemy resistance was to be left to the follow-up elements. The attack was to start at 0600.

A 15cm s FH 18 emplacement. The crew are relaxed, but shells are being fused, so presumably the gun will soon go in to action against an impending Russian attack.

The tanks of 2 Company refuelled quickly in the woods, and the battery went into position. The task force was ready for action.

At 0600, 6 Company began to move. The task force commander and an artillery observer were with the company – the battery gave fire support against specific targets. At 0610 the tanks of 5 Company emerged from the woods in columns of two, formed a wedge, turned southward, and made a wide circle around the hill. The vehicles of the armoured forces infantry 6 Company followed at close distance. As the tanks and armoured forces personnel carriers approached the hill from the south, they were suddenly fired on by Russian machine guns and anti-tank rifles from the top of the hill. The commander of 2 Company slowed down and asked for instructions. The task force commander radioed instructions to engage only those Russians on the hill who obstructed the continuation of the attack. The tanks of 2 Company thereupon deployed and advanced on a broad front, thus offering protection to the personnel carriers which were vulnerable to anti-tank grenades. Soon afterward 5 Company reported that it had neutralised the Russian infantry on the hill and was ready to launch the assault. The task force commander thereupon gave the signal for firing the artillery concentration on the southern edge of the village. Three minutes later 1 and 2 Platoons drove toward the bridge and crossed it in single file, while 6 Company’s tanks approached the crossing site from the west.

As soon as the last tank of 1 and 2 Platoons had crossed the bridge, the other two platoons of 5 Company and the armoured personnel carriers closed up at top speed. The two lead platoons drove through the village and captured the east bridge without encountering any resistance. Russian infantry troops trying to escape northward were overrun by 3 and 4 Platoons and knocked out two retreating Russian tanks at the northern edge of the village. Soon afterward all units reported that they had accomplished their missions.

German signals lorries. These two vehicles are from divisional headquarters.

The task force commander then organised the defence of Village Z, which he was to hold until the arrival of the main body of 3 Panzer Division. Two tank platoons blocked the road leading northward, two protected the east bridge, two armoured infantry platoons set up outposts in the forest east of River B, and the remaining units constituted a reserve force within the village. The artillery battery took up positions on the south bank of the river close to the south bridge. Its guns were zeroed in on the northern and eastern approach roads to the village.

In this action the task force commander made the mistake of ordering Zobel’s advance guard to halt and refuel in the woods 3km (2 miles) west of Village Z. In issuing this order he applied the principle that tanks going into combat must carry sufficient fuel to assure their mobility throughout a day’s fighting. Although this principle is valid in general, it should have been disregarded in this particular instance. Since the element of surprise was of decisive importance for the success of the operation, everything should have been subordinated to catching the Russians unprepared. If necessary, the advance guard should have refuelled as far back as Village X or shortly after crossing River A. Since the woods actually used for the refuelling halt were only 3km (2 miles) from Village Z, the German commander should have foreseen that the noise of starting the tank engines would warn the Russian outposts, which happened to be on the hill south of the village. Moreover, the task force commander should not have stayed behind in Village X, but should have led the advance guard in person. By staying up with the lead elements, he would have been able to exercise better control over both the advance guard and the main body of his force. However, in general the attack by the fully assembled task force was properly planned and its execution met with the expectedly quick success.