* JOHNNY_5 HAS LOGGED OUT *

{faierydust} asshole

{MustacheGirl} Still there girl?

{faierydust} hes banned

{EVLNYMPH} dialup sux

{amy_sullivan} still here

{EVLNYMPH} anybody else lagging?

{faierydust} this is the creepiest thing ive ever done

{MustacheGirl} You should look out the window. See if there’s lights.

{EVLNYMPH} stop with the ufo thing

{MustacheGirl} Have you thought about getting hypnotized? They can recall memories of those nights . . .

{amy_sullivan} no

{amy_sullivan} i don’t even know where ppl go to have that done

{amy_sullivan} sounds like a good way to get molested

{MustacheGirl} Almost midnight.

{EVLNYMPH} i am so freaked out right now i read a book about a navy ship that disappeared

{EVLNYMPH} they found it latr but the crew was all gone and some guys turned up hundreds of miles awy w/no memory

{EVLNYMPH} they think it was sum kind of time pocket or somethin

{faierydust} oh shit

{amy_sullivan} that was a movie. the philadelphia experiment

{MustacheGirl} Yes.

{faierydust} it had tom hanks. the expriment gave him aids

{MustacheGirl} The movie was based on a true story though.

{amy_sullivan} molly is staring

{amy_sullivan} she jumps up on my bed and stares at me til i take her out

{MustacheGirl} I assume the true story wasn’t as interesting.

{EVLNYMPH} im putting on music the quiet is freakin me out

{faierydust} what if its like a wormhole or something

{EVLNYMPH} bob dylan. you gotta serv somebody

{EVLNYMPH} serve

{amy_sullivan} im taking molly outside BRB

{MustacheGirl} AMY!!! Are you nuts?!?!

{amy_sullivan} BRB

{EVLNYMPH} serve

{faierydust} wormhole. i just got the weirdest picture in my head when i thought of that. ugh. worms.

{MustacheGirl} Stupid dog. I’m literally on the edge of my seat and she walks away. This is hurting my butt.

{MustacheGirl} Ew. The cat peed on my bed.

{EVLNYMPH} serve

{MustacheGirl} She NEVER does that.

{faierydust} my science teacher says if all of the worms in the world came up to the surface the world would be buried 20 feet deep in them

{faierydust} he said there are 100000000000000000000000000 sea worms in the ocean 10 w/ 26 zeros

{faierydust} they would flow around the streets like aflood

{EVLNYMPH} serve

{faierydust} there is a world like that i have seen it

{faierydust} people die choking on them

{faierydust} they are consumed from the inside out

{MustacheGirl} All of us find that exact same fate.

{EVLNYMPH} serve

* S_GUTTENBERG HAS LOGGED IN *

{S_GUTTENBERG} HEY GIRLZ!!!!!! I’M TYPING WITH MY COCK. CYBER?

{MustacheGirl} Our race was created as food for worms that do not die. Our eyes are as sweet as candy to them.

{faierydust} eye

{EVLNYMPH} serve

{faierydust} I

{MustacheGirl} None find life outside of the throat. His jaws are like a lover’s embrace.

* S_GUTTENBERG HAS LOGGED OUT *

{MustacheGirl} None

{faierydust} I

{EVLNYMPH} serve

{MustacheGirl} None

{faierydust} BUT

{EVLNYMPH} K

{MustacheGirl} O

{faierydust} R

{EVLNYMPH} R

{MustacheGirl} O

{faierydust} K

{MustacheGirl} It is done.

{faierydust} i just blanked out what time is it KORROK THE SLAVEMASTER KORROK THE KNOWING KORROK THE WISE KORROK THE LIVING KORROK THE FAMISHED KORROK THE CONQUERER KORROK THE GIVER KORROK THE ALMIGHTY I SERVE NONE BUT KORROK

{EVLNYMPH} faierydust are you o

{MustacheGirl} She’s food.

{MustacheGirl} ///////////

{MustacheGirl} ///////////////////////////////////

{MustacheGirl} ///////////////////////////////////

{MustacheGirl} ///////////

{MustacheGirl} ///////////

{MustacheGirl} ///////////

{MustacheGirl} ///////////

{MustacheGirl} ///////////////////////////////////

{MustacheGirl} ///////////////////////////////////

{MustacheGirl} ///////////

* MUSTACHEGIRL HAS LOGGED OUT *

I folded the pages and ran my hand over my mouth, unshaven jaw like sandpaper. Korrok the Slavemaster.

A blue eye in the darkness. Populations of worlds roil in his guts.

As much as I hate being right, I hate it even more when John is right.

Marcy said, “Isn’t that just the weirdest?”

I glanced at Marcy, then at John. Keep in mind, these two had been going out all of ten days.

John said, “Somebody’s got to stay with Amy tonight.”

“Oh, and don’t even get me started on her, John.” I tossed the prints aside. “I mean, did you notice that she’s not even retarded?”

Silence from John’s end, then, “Was she supposed to come back retarded?”

“They had her at that school. Pine View. The alternative school, where they put the retarded kids.”

“That would be the same facility where you went to school for a year?”

“Yes. Pine View.”

A pause on his end, then, “Anyway, I was going to stake out her place tonight—”

“Good plan.”

“—but, Steve called and he needs me and the whole crew on a job site. A chunk of roof caved in, from the ice they say—”

“John, you just made me close down Wally’s so—”

“No, listen. Guess where the job is.”

“Your mom’s ass?”

“The Drain Rooter plant. Right next to Amy’s house. We gotta be on site at five thirty in the morning.”

“I don’t get it.”

“Neither do I, but they gave Steve all these requirements about who could go where, what part of the plant we could be in. Sounded weird, all of it. Plus, I really, really need the money. They’re paying triple time. So can you stay with Amy tonight? See if anything horrifying happens?”

“John, did you read the chat log? Do you remember the—”

A glance at Marcy.

“—thing. In my toolshed? She’s not safe with me, John.”

Marcy’s eyes widened. “You mean there’s something in there other than the dead body?”

I closed my eyes and silently counted to ten.

“Dave, we’ve made it this far. What else are we gonna do, chain you up in your room? I got something else to show you. You see it, you’re gonna want in on this. You ready?”

John unfolded a white piece of paper with a color photo in the center. A printout from a color printer.

“Camera still. From two days ago.”

A grainy shot of Amy’s bedroom. Good light, early evening. Amy standing right there in the center, arms held up, bent at the elbows, one foot lifted off the floor. Motion blur.

I said, “What is she doing?”

“Uh, I think she’s dancing. But that’s not the weird part.”

I knew what the weird part was. There was a black shape behind her, standing there, in the form of a man. Like a body painted in tar, head to toe. The now-familiar image of a man who had been neatly cut from reality . . .

I closed my eyes.

Shiiiiit.

I said to Marcy’s boobs, “What did Amy think?”

“To her,” John said, answering for them, “it’s just a picture of her in the empty room.”

“How is that possible, John? It’s ink on paper. Either it’s there or it’s not.”

“Wouldn’t you be surprised if I somehow knew the answer to that? Marcy doesn’t see it, either. Just you and me. Anyway, I was thinking maybe you could put on a red wig and pajamas and pretend to be Amy. Sleep in her bed, see if they’ll abduct you instead. Will you stay with her?”

Notice the subtle transition from “can you do it” from a few seconds ago to “will you do it.” If I had jumped in and answered “no” to the first one, I’d have been saying I can’t, it’s impossible. If I refuse now, though, I’m saying I won’t do it. I can, but I choose not to because I’m an apathetic asshole. Smooth.

Hmmm . . . what would Marcy’s boobs do in this situation?

“And watch out for Molly. See if she does anything unusual. There’s something I don’t trust about the way she exploded and then came back from the dead like that.”

“I gotta get back to work. Good to see you, Marcy.”

I stood, she stood. She leaned forward and, to my utter shock, threw her arms around me and squeezed.

She sat down and smiled and said, “You looked like you needed a hug.”

How about . . . NOW?!?

“Um, thanks.” I stood awkwardly for a moment, then walked away. From behind me I heard her say to John, “Where was I? Oh, yeah. I ran outside and just then realized I wasn’t wearing pants . . .”

I went back to the store and worked the rest of my shift because I’m a huge dork. Jeff came in at six, took one look at the storm that was salting the air and declared the shop closed for the day.

I stopped by the house to change and saw I had a package in the mail, a thick brown envelope, from an address unknown to me. Handwritten, blocky letters. Little kid writing.

I tore it open and found a pair of cardboard glasses with plastic lenses, a Scooby-Doo logo on the earpiece. A prize from a Burger King kids’ meal. It said “GhostVision” in spooky letters on the side. I put them on, saw a faded cartoon ghost smiling at me. There was a Post-it note inside the envelope that said, “HELP IM A GOST LOOKER 2 MOO MOO MOOOOOO FUCKASS.”

Nice.

I flung it in the passenger seat of the truck, then almost fell on the ice four times on my way to my front door. I knew I needed to shovel the walk before the mailman broke his neck.

Sure. The shovel’s right back there in the toolshed . . .

About an hour later I emerged from the hardware store with a brand-new snow shovel. It was getting late so I went straight to the Sullivan place.

Amy opened the door with the too-happy-too-see-me look I associate with crazy people and dogs. She wore thin wire-framed glasses—she didn’t have them last night but I guess she didn’t wear them to bed—and seemed to have put a lot of work into her hair. Jeans and bare feet with tiny red toenails. It made me cold just looking at them. I observed that she still didn’t have a left hand.

Molly was standing in the entryway, looking at me with utter disinterest. Amy turned around and gestured to me, said, “Look, Molly! David’s here! You remember David!”

The one who made you explode!

The dog turned and walked away, making a sound that I swear was a snort of derision. Amy led me through the living room. The television was on, displaying nothing but the face of a white-haired old man staring quietly at the camera. PBS, probably. There was a picture on the wall, a black velvet Jesus painted in comic-book tones. There was only a lone table lamp in the room, which left about half of the space in shadow.

Of all the creepy places to spend a night . . .

She said, “You look tired! Your eyes are pink.”

“Eh, I haven’t been sleeping. Got a headache.”

Feels like elves tugging on fishhooks in my brain . . .

“Be right back!”

Amy vanished into the kitchen, almost bouncing.

Vicodin.

I sat on the couch and glanced at the TV again, same old guy. Odd-shaped face. He leaned over, whispered to someone just out of frame, then looked back toward the camera again. Weird, because he seemed to be looking at me.

Amy bounced back in, a green Excedrin bottle in her hand and a red Mountain Dew bottle in the crook of her elbow. She nodded her head toward the TV and said, “Cable’s out. I hope you brought something to read.”

I looked at the old guy, looking right back at me.

Oh, SHIT.

The screen blinked, went to black, then came up on MTV. Some reality show with teenage girls screeching at each other.

Amy set the bottle in front of me and said, “Hey, it’s back! I got that cherry Mountain Dew. John said you liked it so blame him if it’s not . . .”

It’s not cherry, dear. It’s RED.

“No, it’s fine, thanks.”

I studied the television. Nobody home but the screeching girls.

Amy said, “It comes and goes. John says that he saw a bunch of birds on the lines and they were flapping their wings but couldn’t take off because their feet had frozen there.”

Without breaking my gaze with the TV, I said, “To John, something being funny is more important than being true.” I glanced at a grandfather clock that was ticking but was off by approximately seven hours.

The television blinked back off, switching to snow.

Amy said, “See?”

I said, “When the TV goes out, it’s just snow?”

“Sure.”

“Never anything else? Like—other programming?”

“No. Why?”

I shrugged. She couldn’t see the old man.

By responding to her attempts at small talk with nothing but ambiguous grunts, I was able to drive Amy back upstairs to her room. I glanced at the grandfather clock . . .

12:10 A.M.

. . . realized again that it was utterly useless, then looked at my watch instead:

7:24 P.M.

This was gonna be a long damned night. I thought absently that maybe if Amy got taken at midnight again I’d be able to duck outta here and go sleep in my own bed. Nobody would notice.

There was a coffee table in front of the sofa and I noticed some magazines resting on a shelf on the end of it. I sifted through them. Cosmo. I picked up the top one and flipped through the pages. Topless woman. Another woman, naked, except for some whipped cream on her naughty bits. Two more pages, a naked man’s ass. I had seen less nudity on Cinemax. I glanced up at the velvet painting and suddenly felt sacrilegious ogling naked models. I stuffed the magazine back in the coffee table and nodded an apology to Badly Drawn Jesus. I looked at my watch again.

7:25 P.M.

I leaned over on the couch and put my feet up. Like lying on a pile of felt-covered bricks. I wondered if I could set all of the clocks ahead to midnight, maybe fool them into coming early.

John and I had looked into the case of a Wisconsin guy who spontaneously combusted while driving his green Oldsmobile last year. We had one witness who claimed the flames formed a huge, satanic hand at the moment of explosion. We went up there, talked to a few people, came up with nothing. Eventually we get a call from a goth kid up there who was heavily into Satan worship. The kid said he had made a pact with Satan to kill both of his parents, then backed out of it when his mom unexpectedly bought him a video game console. The kid, as it turned out, also drove an olive-green Oldsmobile.

The avenging demon—or whatever it was—got the wrong car, barbecued the wrong guy. So they can make mistakes. They can confuse identities. The kid felt terrible about it and from then on spent every night on his knees, praying to God for another chance. For my own safety I pray that Brad Pitt doesn’t do anything to piss off the dark realms.

Eyes getting heavy. A shadow moved on the far wall, probably from passing headlights in the street. My eyes closed.

Open again. Darker. Had time passed? Shadow on the wall again, elongated figure of a man.

No, just the tree outside the window . . .

Another shadow, next to it. Another, a forest of shapes. Moving, slowly. Was I dreaming this? Suddenly there was darkness right in front of me, pitch-black. Two orbs of fire appeared right in the center of it, two burning coals floating right there, inches away.

I flung myself upright, my muscles on fire with adrenaline. The room was normal again. There was still a lone shadow on the far wall, which was in fact just a tree backlit from the front yard. I walked over to it, reached out, and touched it. The shadow didn’t react. That was good.

My watch: 11:43 P.M.

I pounded up the stairs and burst into Amy’s room, terrifying her. She was on the bed with the laptop, legs crossed under her, a handful of what looked like Cheetos frozen halfway to her mouth.

I caught my breath and said, “How can you eat those and type on your computer? Don’t you get that orange shit everywhere?”

“Uh, I . . .”

“Come downstairs. If this thing’s gonna happen, it’s gonna happen. But I want to be on the ground floor and near an exit.”

“Why?”

In case we have to run screaming out of this place.

“And put some shoes on. Just in case.”

11:52 P.M.

The television was back to regularly scheduled programming, the basic cable package of somebody who doesn’t watch a lot of TV. No movie channels. I turned it off and turned to Amy, who was sitting stiffly on the stiff sofa, biting a thumbnail.

She said, “What are we waiting for?”

“Anything. And I do mean anything.”

“Can I ask you something?”

“Sure.” I stalked around the walls of the room, stopping to peer out of the big bay window. Not snowing, at least.

As long as you don’t bring up your brother . . .

“You said yesterday that, like, most of what people say about you guys is true. So—there are some things that I’ve read that, you know . . .”

“What do they say, Amy?”

“That you guys have, like, a cult or something. And that Jim died because of something you guys were into.”

“If that were true, would I admit it?” I glanced at my watch, something that was becoming a compulsion with me.

11:55 P.M.

“I don’t know. You were there, though, right? In Las Vegas?”

“Yeah.”

“And John says he didn’t die in an accident, the way the papers said.”

“What did John say?”

“He said a little monster that looked like a spider with a beak and a blond wig ate him.”

Awkward pause. “You believed him?”

“I thought I would ask you.”

“What are you willing to believe, Amy? Do you believe in ghosts and angels and demons and devils and gods, all that?”

“Sure.”

“Okay. So, if they exist, then to them we’d be like bacteria or viruses, right? Like way lower on the ladder. Now the trick is that a higher being can study and understand the things under it, but not vice versa. We put the virus under the microscope. A virus can’t do the same to us. So if there are things that exist above us humans, beings so radically different and big and complex that they can’t fit inside your brain, we’d be no more equipped to see them than the germs are equipped to see us. Right?”

11:58 P.M.

“Okay.”

“I mean, not without special tools.”

“Okay.”

“John and I have those tools. But just because we can see these things, these odd and weird and horrible things, it don’t mean we can actually understand them or do anything about them.”

“Ooooo-kay.”

“Now let me ask you something. Big Jim, he was into some things, he had unusual hobbies. He built model monsters. But he knew some people, too, didn’t he? Weird people? You know who I’m talking about, right? The black guy with the Jamaican accent?”

She said, “Yeah, I think we talked about that, didn’t we? He was homeless. They found that guy and I heard he, like, exploded. I always wondered about that. Do you think Jim was into something, too?”

There was no short answer to that, so I said nothing. Amy looked at the floor.

11:59 P.M.

Amy said, “So what are we expecting?”

“Anything. Beyond anything.”

She looked very pale. She wrapped her arms tightly around herself, rocking slightly.

“What time is it?”

“Almost time.”

“I’m scared to death, David.”

“That’s good because there’s lots to be afraid of.”

I glanced at Badly Drawn Jesus, then pulled the gun from my pocket. On Judgment Day, I’d be able to proudly state that when I thought the hordes of Hell were coming for a local girl, I stood ready to shoot at them with a small-caliber pistol.

I said, “Keep talking.”

“Um, okay. Let’s see. Keep talking. Talking talking talking, doo doo doo doo doo. Uh, my name is Amy Sullivan and I’m twenty-one years old and, um, I’m really scared right now and I feel like I’m going to pee my pants and my back hurts but I don’t want to take a pill because I think I’ll just throw it back up and this couch is really uncomfortable and I don’t like ham and—this is hard. My mouth is going dry. What time is it now?”

I held my breath, my heart hammering. Anything. Ridiculous, the idea that anything can happen. Impossible. But we should have known from the start. The Big Bang. One moment there was nothing and then, BAM! Everything. What was impossible after that?

12:02 A.M.

I glanced back at Amy. Still there.

“Well,” I said. “They’re late.”

“Maybe they won’t come with you here.”

“Maybe.”

“Or maybe their clock isn’t the same as yours.”

Another good point.

She asked, “Are you scared?”

“Pretty much all the time, yeah.”

“Why? Because of what happened in Las Vegas?”

“Because I sort of looked into Hell, but I still don’t know if there’s a Heaven or not.”

That stopped her.

She finally said, “You saw it?”

“Sort of. I felt it. Heard it, I guess. Screams, bleeding over into my head. And I knew, I knew right then what it would be like.” I took a breath and knew I was about to spill a giant load of stark-raving lunacy.

“It was just like the locker room,” I said. “That day at the high school. Not Pine View where we went to school together, but before that, before they shipped me off there. Billy Hitchcock and four friends. Their hands on me like animal jaws, twisting me, pushing me to the ground. So easy. So fucking easy, the way they overpowered me, and that look, that look of stupid joy on their faces because they knew, they knew that they could do whatever they wanted and they knew that I knew. And that fear, that total hopelessness when I realized I wasn’t going to kick my way out of it and the coach wasn’t gonna come in and break it up and nobody was going to come to my rescue. Whatever they wanted to do was going to happen and happen and happen until they got bored with it and they got so high off that power . . .”

I felt the Smith’s plastic grip digging into my palm, knew I was involuntarily squeezing it.

“Before that, Billy’s neighbor had this little yappy dog, expensive thing. One day the old lady comes home and finds the little yapping thing in her backyard, only it’s not yapping because Billy has taken a hot glue gun and glued its jaws shut. He decided to do the eyes, too, and—look, the point is I think that people live on, forever, outside of time somehow. And I think people like Billy, they never change. And I think they all wind up in the same place, and you and I can wind up right among them and they have forever, literally forever, to do what they want with us. In whatever way people live, maybe you don’t have a body they can cut or bruise or burn but the worst pain isn’t in the nerve endings, is it? Total fear and submission and torment and deprivation and hopelessness, that tidal wave of hopelessness. They never get tired, they never sleep, and you never, ever, ever die. They stay on top of you and they hold you down and down and down, forever.”

I let out a breath.

12:06 A.M.

She said, “Billy Hitchcock. He was the kid who di—”

Her words broke off and she let out an enormous snore, like she’d suddenly fallen into a deep sleep in midsentence.

I turned, and where Amy had been sitting there was now a human-shaped thing with jointed arms and gray rags for clothes, legs sticking stiffly out in front. Like a department store mannequin crafted by a blind man. The red hair looked to be made of copper wire. A hinged jaw clamped shut and the snoring sound was clipped immediately. Two seconds later the jaw yawned wide open again and the enormous snoring sound poured forth—a sound that was more mechanical than human. Artificial.

I got to hand it to them, I thought. I really wasn’t expecting that.

I heard a clump and realized the gun had fallen out of my limp hand. I also realized my jaw was hanging open. I tried to pull myself together, forced my legs to step forward. I reached out toward the thing—

The gun was back in my hand. Amy was back on the couch, sitting bolt upright, looking blankly into space. I immediately looked at my watch—

3:20 A.M.

SHIT.

Amy slowly turned her head, coming to. She saw me, saw the look on my face. Realization washed over her and her hand flew to her mouth, her eyes suddenly wide.

“Did it—did it happen? It happened, didn’t it?”

I said, “Go upstairs and pack as much stuff as you can carry. We’re getting outta here.”

She bounded down the stairs seven minutes later, a satchel over her shoulder and the laptop under her arm.

We found Molly in the kitchen, standing on a chair and eating from a box of cookies that had been left open on the table. After some coaxing and threats we got her to follow us out to my truck. We loaded up, the engine growled to life. The windshield was a solid sheet of white.

Amy found the cardboard GhostVision glasses on the dashboard and examined them with a quizzical look. I found my ice scraper from under my seat and jumped out to scrape the ice from the windows. Outside I turned toward the house–

I stopped in my tracks.

I mumbled, “Oh, shit, shit, shit.”

There was a figure on the roof, silhouetted against the pearly moonlit clouds. Nothing but silhouette, a walking shadow. Two tiny, glowing eyes.

“What are you looking at?”

Amy, trying to follow my gaze.

“You can’t see it.”

She squinted. “No.”

“Get back in the truck!”

In a series of frantic bursts I managed to scrape a lookhole in the powdered-sugar crust of ice on the windshield, then jogged around to the back to do the same.

I heard Amy say, “Hey! What’s he doing up there?”

I leaned around the truck and saw Amy was wearing the Scooby-Doo ghost glasses and was staring right at the spot where Shadow Man was standing. She pulled off the glasses and looked at them in amazement, then looked through them again and said, “What is that thing? Look! What is it?”

“What—are you using the damned Scooby glasses?”

“I can see it! It’s a black shape and . . . it’s moving! Look!”

I did look, long enough to see the shape spout giant black wings. No . . . that wasn’t right. It became wings, two flapping wing shapes that didn’t quite meet in the middle. It flitted into the sky, a black slip against the clouds, higher and higher until it vanished.

I heard barking. Molly had gotten out of the truck, was at my knees.

Amy kept staring up, her mouth hanging open, steam jumping out in little puffs. She said, “David, what was it?”

“How should I know? They’re shadow people. They’re walking death. They take you and you’re gone and nobody knows you were ever there.”

“You’ve seen them before?”

“More and more. Let’s go, let’s go.”

We climbed in, called to Molly. She didn’t move, stood stiffly, trembling, growling at the sky. I called to her again, got out, picked her up and threw her inside.

I jumped in, floored it.

We fired down the road, fishtailing on the glaze of skating-rink-caliber black ice left over from the road graters. The house shrank in the rearview mirror. Beyond it, the low, flat Drain Rooter factory.

Amy twisted in her seat and peered back through the rear window, then did the same with those stupid ghost glasses. Molly was up and dancing behind us, bouncing around, probably thinking she’d be safer out on foot. Amy squealed, “Look! Look!”

I gave it a glance in the mirror, saw high headlights behind us, probably a Rooter truck leaving with a load. I did something they don’t teach you in driving class, which was to lean my head out into the blistering wind and look up, steering blind with one hand.

Black shapes were swirling overhead, winged things and long, whipping forms like serpents. Swirling, stopping, turning, like bits of debris in a tornado.

They were congregating around the factory.

Most of them were. Some of them were breaking off and following us, dark shapes flitting across the sky and into the shadowy trees and houses around us, vanishing from view. I pulled in my head and focused on the road.

Amy sat forward and strapped her seat belt on, screamed, “What do we do?”

Another glance into the mirror, headlights closer now. Trucker hauling ass, hauling drain cleaner.

A shadow flicked across the hood.

I stomped the brakes, the Bronco spun out, skidded, plowed ass-first into a bumper-high snowdrift alongside the road. Silence for a second, then the apocalyptic sound of eighteen wheels skidding on ice.

The semi jackknifed, the front end stopping and the heavier rear still pushing forward, toward us. A giant cartoon plumber, a red “X” through him, loomed in the windshield.

The trailer skidded to a stop about six feet from the bumper, then rocked threateningly back and forth, deciding whether or not it wanted to tip, clumps of snow spilling off the roof with each sway.

Silence, save for the tick of the engine and the rushing of the wind. Finally, Amy said, “Are you all right?”

“Uh, yeah.”

I was scanning the sky for shadows. I glanced at the red cab of the semi, could see somebody moving inside. An elbow.

A hand clamped on my arm. Amy whispered, “There. Over there.”

She was pointing, with her handless wrist, God bless her, at a black shape growing on the side of the semi, several shapes, molding together, forming something like a spider. Sitting there on the white wall of the trailer like a piece of black spray-painted gang graffiti.

The little hand clamped tighter on my forearm, hard, like a blood-pressure cuff. A low growl from Molly, who had backed up all the way to the rear wall of the Bronco, pressed against the rear door like she was trying to escape by osmosis.

“David, go. Go.” Amy was whispering it hard, harsh hisses of “GO GO GO GO GO . . .”

I slammed on the gas. The tires spun. Spun and spun and spun. Four-wheel drive. Two wheels buried in packed snow, two wheels spinning on ice.

The shadow spider moved, blurred, flicked across the length of the tractor trailer and appeared right next to the cab. Just a few feet from the driver inside. I threw the Bronco into reverse, then forward, rocking out of the ruts dug by the spinning tires, praying for traction.

“David!”

I looked up. The spider shape was gone.

I heard screams, curses. Rage. The driver had stumbled out of the cab, a big guy, tall and fat, a goatee.

The man was ranting, spit flying from his mouth, staring us down, fists clenched. Face pink with the effort of it. He turned his eyes on us. A rabid dog. “Cunt blood fucking cunt motherfuckers—”

Maybe he thinks we’re plumbers . . .

He stomped toward us and I could see them now, shapes moving around him, shadows wrapping around him like black ribbons twisting in the wind. And his eyes. His eyes were pure black now, the pupils and the whites gone in coal-black holes.

A few feet away from us now, trudging toward us like a robot. I slammed on the gas again, spun again, felt the rear end shift and then settle in, the tires making a pathetic, wet whine against the slush. A thin arm shot across my chest and it was Amy, reaching over and slapping the lock shut on my door a millisecond before the truck driver started clawing at the handle.

Crazed curses muffled by the door, his breath steaming up the glass. Tires whirring against ice. “FUCK YOU MOTHERFUCKING MOTHERFUCKERS EAT YOUR FUCKING—” A meaty hand smacked the glass.

The curses were replaced by a long, howling scream. The man stumbled back as if shot, a hand flying to his forehead. He stumbled, went to a knee, screeched like a saw blade on metal plate.

He exploded.

Limbs flew, flecks of red splattered over the windshield, Amy screamed. A head tumbled through the air, landed on the road and bounced out of sight. The tire sounds stopped. I realized I had let off the gas, was gawking at the looping remains of the man’s intestines, steaming in the frozen air.

The shadows, restless again. Crawling over the truck and the snowy ground around us, the things as stark as black felt in the snow-reflected moonlight. A tall one grew in front of us, almost the shape of a man but without a visible head and with too many arms. Molly went wild, barking and barking and barking, then melting into high, breathy whimpers.

I stomped the gas pedal one more time, got the tires spinning, heard bits of ice and dirt smack the fenders. The shape moved toward us, melting into the hood, walking through the engine block, moving across the hood like wading into a pond. It reached up with an arm, an arm as long as a man, then plunged it into the hood. The engine died instantly. The headlights went dark.

Shadow everywhere now. Movement, hints of it through the moonlight. Amy breathing next to me, quick, nervous gasps. For a long time, nothing happened.

She mumbled something, too low to hear. I glanced at her; she leaned in and said, “I don’t think they can see us.”

I didn’t get it at first but it almost made sense. Whatever they were, they didn’t have corneas and pupils and optic nerves. We couldn’t see them, normally. They were sensing us, feeling us out, searching without seeing.

I looked up, saw one shape flit away and disappear into the sky. Another, floating past the semi trailer, crawling over the plumber logo, then dissolving into the darkness.

I nodded, slowly, whispered, “They don’t belong here, in this world. They’re flying blind, with no eyes to—”

A soft thump on the window. Amy screamed.

Outside my window, inches from my face, was the severed head of the truck driver. A six-inch hunk of spinal column dangled from his neck, hanging in midair. His eyes were wide open, no sign of lids, two orbs twitching this way and that, taking us in. Amy was still screaming. Some lungs, that girl.

“Amy!”

The head pressed up against the window, squishing its nose, cramming its eyeball against the glass to get a look in. Its mouth hung open, lips pressed against the glass, teeth scraping.

“Amy! Plug your ears!”

She looked at me, saw me pull out the gun, pressed her forearms over the side of her head. I started rolling down my window.

I created a gap of about six inches when the head tried to ram into the opening, jaws working, teeth snapping. I jammed the gun in its mouth and squeezed the trigger.

Thunder. The head disintegrated, became a red mist and a rain of bone chips. I glanced at the gun, impressed, wondered about the loads the stranger had sent me. I leaned to the window and screamed, “You should have quit while you were a—”

“David!”

I turned. Darkness was falling around us now, pooling, the clouds over us vanishing behind living shadow. Suddenly it was dark, cave dark, coffin dark. I opened my mouth to tell Amy to run, to run and leave me behind because it was me they wanted and not her, but nothing came out.

I twisted the key, the engine turned over, stalled. I tried again, it fired to life, I stomped the gas. I floored it and we went nowhere, nowhere, nowhere and then lurched forward, across an unseen street, smacking into the drift on the other side of the road. I threw it in reverse, floored it again, spinning out and then crawling forward—

We were off. Out of the blackness and into the night, eating up the street, my hands strangling the wheel. The speedometer crept up, tires floating under us, like driving a hovercraft. I felt a hand on my arm again, Amy, breathing, whipping her head around, trying to see everything at once through the ridiculous cardboard glasses.

The night outside got darker and darker, shapes swirling around, blackness closing in, swimming in it, like being downwind from a forest fire.

And suddenly, Amy was gone. An empty seat.

And then I felt stupid.

Of course the seat was empty—I came out here alone and we had never found Amy; the house had been empty and we all knew she was actually wrapped up in a tarp in my—

The darkness swallowed me. The passing scenery outside was gone, no houses or grass or snowdrifts, like driving in deep space.

Shadow poured into the Bronco like floodwater. A blade of ice pierced my chest, cold flowing in like poison. My heart stopped. It was like strong, cold fingers reaching behind my ribs and squeezing.

And then I was gone, out of the truck, out of anywhere. A storm of images exploded in my head, crazed mental snapshots like fever dreams:

—looking down, a black crayon in my hand, drawing pictures of three stick figures. One drawn with long hair, one shorter with a spray of red at the top—

—under my car, my old car, my Hyundai. On my back, another guy next to me, long blond hair. I’m holding up a muffler and he’s threading in bolts, and I tell Todd we’re missing a bolt, that it rolled away, and he’s saying that the jack is tilting and GET OUT GET OUT BECAUSE THE CAR IS FALLING—

—running, breathing hard, through a ballroom in a Las Vegas casino. Chaos, then seeing Jim and knowing what I had to do, raising and firing and watching him go down, clutching his neck—

—blue canvas, knees in the snow, rolling a body, rolling it up because somebody could show up any second and it’s sooooo hard to move the deadweight—

Back. In the truck again, fingers clamped on the wheel. Plowing through deep snow, a mailbox flying toward me.

“David!”

I was driving in somebody’s front yard. I cranked the wheel, ground through a drift and landed in the street again. I saw Amy was back, in the passenger seat, pale as china. I reached over and grabbed her by the arm, pulled her over, like I could somehow stop her from getting sucked out of reality again if I hung on really, really tight. She screamed, “The light! Go to the light!”

No idea what she was going on about. Then I saw it, a pool of light in the pitch blackness just ahead. A flat of parking lot, a hint of an unlit red sign.

It was getting darker, blackness eating up the landscape around me, a power outage during a lunar eclipse. I cranked toward the embankment and jumped the curb, climbed over a little hill then landed with a lurch. I slammed the brakes, spinning on a white plane as flat as a hockey rink.

We smacked a pole, light bathing the interior. I saw out of the rearview mirror the sign for a new doughnut shop, the place still under construction but the parking lot lights on. And then I saw nothing at all, because blackness settled over everything outside the little island of lit snow we had settled in. In a second we were cut off from the universe, nothing in any direction, like we had submerged in a lake of oil five hundred feet under the ocean floor. Just black and black and black.

Silence. The sound of two people breathing. I felt a wet nose at my ear, saw Molly poking her head up, wagging her tail, bouncing back and forth on her paws, growling low under her breath.

Amy said, “They can’t get us! They can’t get us in the light! I knew it!”

“How did you—”

“David,” she said, rolling her eyes, “they’re shadow people.”

She rolled down her window, poked her head out into the night and screamed, “Screw you!”

“Amy, I’d prefer that you not do that.”

She pulled back in and said, “My heart’s going a thousand miles an hour.”

I looked out into the nothing, found the gun in my lap and squeezed it. A good luck charm at this point, and barely that.

Amy said, “Ooh! Look at that. What is—”

Little bits of light, moving around in the darkness in pairs. Twin embers, small as lit cigarettes, floating slowly around us. There were a few and then a few more, until dozens of the fiery eyes were peering in at us. And then, through the windshield, I saw color. A thin line of electric blue across the darkness, like a horizon. Then the blue line grew fat in the middle, expanding, widening like a slit cut in black cloth. It expanded until blue was all that was visible through the windshield.

It was an eye. The eye. Vibrant blue with a dark, vertical reptilian slit of a pupil. The hand on my forearm again. I thought Amy was going to break the bone with her grip. The eye twitched, taking us in. Then it blinked, and was gone.

The shroud of blackness was gone, too. Just the night now, shrouded stars and moonlit snow and a sad, dormant doughnut shop.

Amy said, “Are—are they gone?”

“They’re never gone.”

“What was that?”

Well you see, Amy, it’s like this. We are under the eye of Korrok. We are his food, and our screams are his Tabasco sauce.

Instead I said, “I’m not leaving the light.”

“No.”

Amy craned her head around, looking in all directions again, then took off the cardboard glasses. I looked down at the Smith and realized something, probably several minutes too late. I grabbed the barrel and offered it to Amy, butt-first.

I whispered, “Take this.”

“What? No.”

“Amy, that thing, with the truck driver? You saw how they took him over, used his body? Well that same thing can happen to me.”

And don’t ask me how I know that, honey.

“No, David—”

“Amy, listen to me. If I start acting weird, if I make a move at you, you need to shoot me.”

“I wouldn’t even know how to—”

“It’s not complicated. The safety is off. Just squeeze. And don’t get cute and try to go for my arm or some shit like that. You’ll miss. Just aim for the middle of me, jam it into my ribs. Shoot and get out, run for it. Don’t, you know, keep shooting me. Please, take it.”

To my surprise, she did. She turned the pistol over, the gun looking huge in her little hand. She said, “Well, what if it happens to me? What if they take me instead?”

“I can overpower you if I have to, get the gun away. But I don’t think it’ll happen. Not with you.”

“Why?”

I leaned back, suddenly feeling lighter without the gun. I swear the things generate their own gravity.

“It’s just a theory I have.”

Amy pulled her feet up on the seat and scrunched against me, shivering. The gun was in her right hand, laying across her hip and pointing vaguely at my crotch. There would be some real symbolism there, I thought, if this turned out to be a dream.

I said, “Besides, I don’t need the gun.” I held up my hands and said, “They passed a law that said I couldn’t put my hands in my pockets. Do you know why? Because they would become concealed weapons. I can kill a man with these hands. Or just one of my feet.”

She snorted a dry, nervous laugh and said, “Yeah, okay. I’ll watch out for you then.”

I again gripped the steering wheel with both hands, tendons tensing across my forearms like cables. I sat like that, in silence, for an eternity of minutes. A whole bunch of words trapped behind clenched teeth.

Finally, I closed my eyes and said, “Okay. Look. You need to understand something. About this situation, who you’re trapped in here with.”

She twisted around to face me. Those eyes were so damned green. Like a cat. “Don’t, just—just listen. Do you know why I was in the special school, why I was in the BD class in Pine View?”

She said, “Sort of. The thing with Billy, right? The fight you got into with him? And then later when he—”

“Yes, that’s right. Listen. Men are animals. Get us together, take out the authority figures, and it’s Lord of the Flies. Billy and his gang, a couple of guys on the wrestling team, they used to make these videos. The kid, you know the Patterson kid, kind of fat? Anyway, they got him after school and tied him to a goalpost and shaved his head and all that, and it was hours before somebody found him, and by then, you know, the skin on his face was all blistered from the contact with the feces . . .”

Maybe you can cut back on the details a bit, hmmm?

“. . . and they have this party and they show the tape, show the tape of them torturing this fat kid and him just screaming. And they sat there with their beers and watched that tape over and over and over and that’s the way it is in high school. Shit that would get an adult put in a straightjacket is just brushed off. ‘Boys will be boys.’ ”

I hesitated, scanned the night for something, anything. I saw a lone bird on a power line, flapping its wings, but it didn’t seem to be going anywhere.

“Anyway, the Hitchcock guys, I had gym with them and they picked me outta the crowd. It became this daily thing. Little shit at first but they kept pushing it further and further and it took more and more to keep them entertained. And the coach there, he hated me, so he would make sure and not be there. I mean, I literally saw him turn his back and leave the room when they came after me one time, made sure I saw him do it. And one day they got on me and took me to this equipment room in back, this little storage area with shoulder pads and wrestling mats stacked all around and it’s hot as an oven and there’s this moldy smell of old sweat fermenting in foam padding. And things got crazy. Like, prison yard crazy. And eventually it ends and they leave me there and they’re walking out through the locker room and . . .”

Hmmmm . . . would she notice if I suddenly changed the subject?

“Well, I had taken to bringing a knife to school, not a switchblade or anything cool but a little two-inch blade on my key chain. It was all I had. And I get this blade free and I get behind Billy and I slice him, right up his back, a shallow little cut up his spine. It wasn’t deep but it got his attention and he fell over, thinking he was dead, blood all over the bench and the floor. And I got on him, sat on his chest and I started jabbing at his face, cutting, the blade bouncing off bone in his forehead and blood and . . .”

I thought long and hard about how to dress up this next part, but couldn’t think of a way. I wondered when the doughnut shop was scheduled to open.

Filling in the silence, Amy asked, “What did they do to you?”

“Let’s put it this way. I’ll never, ever tell you.”

She had no answer, which either meant she was totally unfamiliar with the concept or very well familiar. I pressed on.

“So, I wound up—”

—cutting out his eyes—

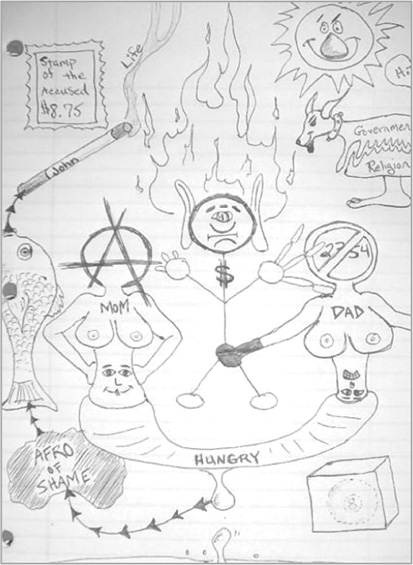

“—hurting him pretty bad, he lost his eyesight. I mean, like, legally blind. I wound up getting charged with aggravated assault and several other things that are all synonyms for aggravated assault. The school was talking a permanent expulsion. My dad—my adoptive dad—he’s a lawyer, you know, he had a series of meetings with the school and the prosecutor and it was a mess. They wound up testing me for mental illness, which I knew even at the time was a way to get me off because the case could be made that the school should have protected Billy from me, should have diagnosed me, whatever. I met with a counselor who had me talk about my mom and look at inkblots and roleplay with puppets and draw a picture of how I viewed my place in the world. . . .

. . . and I knew it was a scam, a lawyer trick, but I kept picturing Coach Wilson turning his back, again and again and I figured, hey, screw them. The prosecutor, this bearded Jewish tough guy, didn’t want to push the charges. He said it was a five-on-one fight and shit happens, didn’t want to see me disappear into the jaws of the juvie justice system. The school backed off on the expulsion under threat of lawsuit and, bada-boom, I wind up spending my final year at Pine View.”

A speck of crystal landed on the windshield. A lone snowflake. Another landed a few inches away.

“So,” I said, “four months later Billy is adjusting to life without eyes, saying good-bye to sports and driving and independence and knowing what his food looks like before he eats it and never knowing if a fly has landed in his soup. He takes all of his pain pills at once. Demerol, I think. They find him dead the next day.”

Silence. Desperate to hear her say something, anything, I asked, “So how much of that story did you already know?”

“Most of it. There was a weird rumor that went around that you had snuck into his room and poisoned him or something stupid like that, with rat poison or something, which was stupid because the police would have noticed that.”

“Right, right.”

I started that rumor, by the way.

“You must have felt horrible when you found out. About Billy, I mean. That’d be awful.”

“Yeah.”

Nope.

What followed was the longest and most tense conversation pause of my life, like being stuck on a Ferris wheel with somebody you just puked on. Exactly like that, by the way. The truth was, I didn’t feel sorry for Billy. He teased a dog and got his fingers bitten off. Fuck him. Fuck everybody. And fuck you, Amy, for somehow getting me to tell you this. Sure, yeah, I felt bad about it, Your Honor. And that day years ago when I heard about the kids shooting up the school in Colorado I shook my head and said it was a tragedy, an awful tragedy, but inside I was thinking the look on the jocks’ faces when they saw the guns must have been fucking priceless. So, yeah, as far as you know, I felt just as bad about Billy as a good person would. And I’ll never, ever tell you otherwise. Never.

She said, “Still, who knows what he would have done to somebody else if you hadn’t—”

“I don’t feel bad about it, Amy. I lied about that part. When I heard, I felt nothing at all. I thought I would, I didn’t. The guilt just wasn’t there because I’m not that type of person. And that’s what I’ve been saying, that’s why you’re in danger here. I don’t think those things, those bits of walking nothing can use you, but I think they’d know me as one of their own. So keep the gun on me. And keep your finger along the side of the trigger and be ready to squeeze it as hard and as fast as you can.”

Silence again. Did I say that last silence was the longest and most awkward of my life? The record didn’t stand for long.

I would give everything I own to somehow take this conversation back.

I said, “We have no idea what they were doing to you, Amy, when those things took you all of those times. But they’re not going to do it again. This being scared bullshit, it’s exhausting for me. And you know, I reach a point where I say, you can kill me or tear off my arms or soak me in gasoline and set me on fire, but you won’t keep me like this, imprisoned by fear. Now, after everything I’ve seen, I’m not really scared of monsters and demons and whatever they are. I’m only scared of one thing and that’s the fear. Living with that fear, with intimidation. A boot on my neck. I won’t live like that. I won’t. I wouldn’t then and I won’t now.”

After a long time she said, “What do we do?”

“We sit here. Just keep the gun on me, okay? We’ll sit here and wait for the sun. Then I’ll talk to John. John will know what to do.”

I can’t believe you just said that.