9

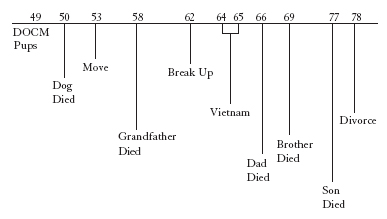

The Loss History Graph

Now that you’ve established that myths, intellect, and short-term energy-relieving behaviors have not been providing the kind of long-term benefits needed, you might have begun to feel stuck. This is the point at which you may have started to “act recovered.” That’s when you say, “I’m fine,” when you really mean, “I’m hurting.” This is a dangerous place to wind up.

If there were some magical way that we could lift the pain of your losses off your shoulders, we would. But we can’t, so we’ll do the next best thing. We will teach you how to complete your relationship to the pain caused by the loss.

The loss history graph is designed to help you discover what losses have occurred in your life and which of them are most restricting your day-to-day living. At first glance, it might seem strange for us to tell you that you need to identify the losses in your life. After all, shouldn’t you know what they are? Sadly, many people, particularly when they were young, were taught to compare losses and minimize feelings. Thus, they may not be aware of the emotions they have from past events that continue to limit their lives.

Somewhere during your formative years, you heard the statement, “I cried because I had no shoes until I met a man who had no feet.” Clearly, this statement is designed to get people to pause and be grateful for what they have rather than focus on what they don’t have. While that is an admirable quality, it is often construed to mean, “Compare losses to minimize feelings.”

Russell remembers a dinner party where he was seated next to two women friends. One woman’s husband had died of cancer several months earlier. The other woman was in the middle of a painful divorce. Russell asked her how she was doing. She whispered, “Terrible, but I can’t feel bad about my divorce because her husband died.” This is a perfect example of compare and minimize.

Once we establish a habit, we continue to use it unconsciously. Our lives are made up of many habits. You’ve probably been putting on the same shoe first all your life and never thought about it until right now. This is also probably true of how you’ve been trying to deal with the losses in your life. That’s why a Loss History Graph is so important. We need to know what our pattern is so we can confront and change it.

The primary purpose of this exercise is to create a detailed examination of the loss events in your life and to identify the patterns that have resulted from them. There are several other reasons for making a Loss History Graph. One is to bring everything up to the surface where we can look at it. Buried or forgotten losses can extend the pain and frustration associated with unresolved grief. Another is to practice being totally truthful. We can often be dishonest without ever lying. That is, we omit things and thereby create an inaccurate picture. An additional benefit of using this exercise is observing which short-term relievers we have relied upon after losses.

We’re all going to have other losses during our lives, and we don’t want to fall into the same old traps. As the old mountain man told the young mountain man, “If you want to avoid bear traps, it’s a good idea to know what they look like.”

In order to do a Loss History Graph, it’s a good idea to know what it looks like. Here are ours.

JOHN W. JAMES

BORN: February 16, 1944

’49 Puppies—As a starting point, I’ll tell you about my dawn of conscious memory. My first memory is from the day our family dog gave birth to a litter of puppies. Late one night, after my brother and I had gone to sleep, our father woke us up. He took us to the dog’s bed. Our dog, who had always been friendly, seemed to be suspicious and wary. I remember being a little frightened. As my dad brought us closer to the bed, I could see three or four little lumps near her. Soon she began to whine and move around. I thought that she was in pain and wanted to help her. My father told us to stay back, that she was having trouble delivering one of the puppies. When he said that, it dawned on me what the little lumps were. I was happy, scared, proud, and confused all at the same time. Eventually, my father had to help her give birth to the last three puppies.

My brother and I wanted to hold and pet the puppies right away, but we were told that our dog might not like that, so we went back to bed. Of course, we couldn’t sleep and spent half the night talking about this wondrous event. The next two weeks were spent being solicitous of our dog and waiting for the puppies to open their eyes.

This event is the very first conscious memory that I’ve been able to identify. I have no earlier recollection of anything.

’50 Dog—My dog died (as discussed in chapter 3).

’53 Moving—This was the year we moved for the first time. Moving is a major loss for children. My parents explained all the intellectual reasons why we were moving: we would live in a better neighborhood and a better house, it was closer to school, and we would own it rather than rent. That didn’t make the move feel any better. I was going to miss my friends.

’58 Grandfather—My grandfather died.

’62 Girlfriend—My girlfriend and I broke up.

’64/65 Vietnam—The way Vietnam veterans were treated in our society reinforced the loss-of-trust experience. It is this loss of trust that causes so many problems for veterans even to this day. As a society, we have paid and are still paying dearly for this. During the years of the war, we suffered the deaths of more than fifty-eight thousand combat troops; in the years since the war ended, we have felt the loss by suicide of more than three times that number.

’66 Father—My father died. I had seen him only once since I came home from overseas; much was unfinished in our relationship. His drinking had continued until it finally killed him. It was a very painful experience for me.

’69 Brother—My younger brother, a twenty-year-old pole vaulter at Southern Illinois University, was in perfect health when he died. He was on his way to visit me in southern California, where I lived at the time. He was traveling with two of his friends from college; they’d stopped for the night and had all decided to take a nap. Later that afternoon, when his friends went to wake him, they found that he had died.

I spent days trying to find some intellectual reason for his death, and when I couldn’t find one, I assigned blame for his death to God.

’77 Son—My son died. Two years earlier, my wife and I had had a daughter. Her arrival was the high point of my life. When my wife became pregnant again, I was looking forward to another such experience. About five months into the pregnancy, complications set in. When my wife went into premature labor, we raced to the hospital, where every possible medical technique was employed to slow or stop the process. She was hooked up to monitoring devices, and for two days we had to listen to a perfectly healthy heartbeat while knowing there was little chance the child would live.

All of my life I had been taught to believe certain things about what my job was as a man, a husband, and a father. I had been taught to believe that it was my job to identify problems and solve them. What I discovered right away was that it did not matter who I knew, what I knew, how much money I had, or how intelligent I was—there was nothing I could do. It was the most frustrating experience I had ever had.

Despite all the medical intervention, our son was born. For the first eight hours, it appeared that everything would be all right. Then things started to go wrong. Once again, identifying the problem was easy. I could see the problem: he weighed about two pounds, had black hair, and was encased in a glass box. But there was nothing I could do but stand and look at all the monitoring equipment and feel impotent.

This went on for two days. I was trying to help my wife because that was what I had been taught to do. There is nothing wrong with that except, in trying to help her, I was not acknowledging my own pain. At the end of the second day, my son just breathed out and never breathed in again.

If you can believe this, it started to go downhill from there. The things people said and did were shocking. That my wife and I were unable to talk became apparent. Our relationship began to fall apart immediately. During the next eight months, I went everywhere, talked to everyone, and read everything that I could get my hands on to help ease the pain. This was the point where I discovered there was little or no help available to deal with the grief. That was real despair.

’78 Divorce—My wife and I were divorced. The divorce happened because we had no idea how to deal with the grief caused by all the changes in our lives. We were newly married, new parents, and new grievers, all at the same time. The death of our son was the straw that broke the camel’s back.

In typical griever fashion, my mind was preoccupied with thoughts of what I wished I had done different, better, or more. If I hadn’t made the cost of medical bills such an issue, my wife might have gone for checkups more frequently. The night the emergency started, we had no baby-sitter and no real idea of the seriousness of my wife’s condition, so I didn’t go with her to the doctor’s office. I used to sit and think about how frightening that must have been for her. Even as all of these thoughts were running through my mind, I had no skill or practice at being able to talk about what I was feeling. I felt isolated and alone, yet I truly believed that I was supposed to be strong and keep it all inside. Since that was all I knew, that is what I did. With that type of pressure building up, arguments became common. Hurt feelings were then added to the fire, and more arguments followed. At the same time, my wife was thinking that if she hadn’t gotten pregnant so soon after the birth of our daughter, then none of this would have happened. That was her different, better, or more thinking. She too had no knowledge about the importance of talking about her feelings.

When communication breaks down in a marriage, no matter the cause, it is only a matter of time before divorce occurs. When the divorce takes place, we have yet another grieving experience to deal with, so the cycle continues.

While writing this book, I called my former wife to discuss her thoughts about telling this part of the story. One of the things she shared with me was the fact that she had not known for several years how much the death of our son affected me. How could she have possibly known? I was an academy award griever then.

Setting out to do a Loss History Graph can be a scary proposition. So before we ask you to do this exercise, we want you to see another example.

Here is Russell’s loss history graph.

RUSSELL FRIEDMAN

BORN: January 4, 1943

’47 Dawn of Conscious Memory—My first conscious memory is neither happy nor sad. It is a simple memory of a blue bedspread. It was covered with nautical designs.

’48 Little Blue Jacket—My father took me to a Rochester Royals basketball game. At the game, he bought me a Royals jacket. Some time later, I lost the jacket. When my father found out that the jacket was lost, he berated me for losing it. I remember feeling as if my father was no longer safe for me. After several other incidents of this type, I did not trust him anymore.

’51 Feeling Different, Plus Major Move—I was born allergic to milk, eggs, nuts, and chocolate. One of the consequences of the allergies was the need to have special food when I went to school. I felt very different from the other kids in my class. I also had very, very red hair, and approximately two and a half million freckles. That may sound cute. But as the possessor, it did not feel cute. I was teased often and sometimes cruelly by the other children. I did not have the wherewithal to defend myself. I just felt so terribly different.

We lived in Rochester, New York, which gets very cold and damp in the winters. I suffered with asthma. It was so serious that my parents were advised to move to either Arizona or Florida for the heat. I did not want to leave my friends and the neighborhood to which I had grown accustomed. I made an emotional appeal to my parents. My appeal was met with intellectual explanations about a better school, a bigger house, and Daddy having a better job. My presenting emotions about my friends was never addressed.

We moved to Florida. In Florida, another physical problem surfaced that has had lifelong consequences. Having red hair and very light skin, Miami’s intense heat and deadly ultraviolet rays had an immediate impact on my life. I was forced to wear shirts in the swimming pool and zinc oxide on my face so I could play outdoors. I suffered a few serious sunburns and also developed a fear of the sun. It started to affect my choice of activities, affecting in turn my friendships with my peers. The bottom line for me was that my red hair, fair skin, and freckles made me feel very different from everyone else.

’57 Grandma—Grandma died. She had been living with us since my mom had gone back to work. Grandma was the primary caretaker for my brother, who is ten years younger than me. This is where I learned to “be strong for others.”

’64 Broken Engagement—This was my first full-fledged love affair, with major plans for marriage and children. When it crashed and burned, I was devastated. I had absolutely no ideas, tools, or skills to help me deal with the intense emotional pain. I was in my last year of college. I cut classes. I stared at walls. I just went through the motions.

’64 College Graduation—Traditionally, graduations are perceived as positive experiences. And that is at least half true. I was torn, however, between the excitement and freedom of my new adult status and the sadness of leaving behind four years of people and places and familiarity. No one wanted to hear about or acknowledge the sad part.

’68 Grandpa—Grandpa died. I was not fond of my grandfather. He was very gruff, and I was scared of him. Even as I got older, I found his manner threatening. When he died, he and his son, my dad, had not been on good terms. I tried to “be strong” for my dad.

’72 First Divorce—This divorce was totally unexpected for me. I did not have an inkling that it might happen. I was devastated. I was confused. I was totally lost. The only tool I had for dealing with any kind of loss was “be strong for others.” But this was me. I was the other. As I look back on it, I am amazed that I am still alive. I cannot imagine how I drove a car without accidentally killing myself or anybody else. It was almost impossible for me to concentrate. Even then, I knew that this loss was not singular. I had a sense that in addition to the loss of the marriage, there was the loss of all my hopes, dreams, and expectations, coupled with a massive “loss of trust.” Since trust had always been a major problem for me, this divorce and how it happened crushed what little trust I had left.

’73 Closed Business—When my wife and I divorced, I kept the restaurant we had opened together. I was preoccupied with the emotions caused by the divorce. I had no effective skills for dealing with those painful emotions. While I had normally been a fairly attentive entrepreneur, my concentration was greatly diminished. I started making some very poor business decisions, which, in turn, led to poorer ones. In the end, I closed the business down. My heart was not in it anymore.

’86 Second Divorce—This divorce was very different from the first one. The pain was intense. In addition to the death of the relationship and the hopes and dreams, another factor troubled me greatly. I was forty-three years old. My sense of myself, my life, and my future was different from what it had been after my first divorce. I was older. My business was in a neighborhood populated with elderly people. I used to sit and stare at the elderly couples, thinking, “When do I get to go off into the sunset with someone?” My parents and my wife’s parents were still together. I was 0 for 2 in marriage. I felt like a complete failure.

’87 Bankruptcy—Having experienced a first divorce and closing a business in response to it did not prepare me for the second divorce and the financial tragedy that followed. In fact, the earlier events almost predicted the later ones. I was practiced at divorce, so I got another one. I was practiced at business failure, so I failed again. In neither case had I experienced recovery or completion of the emotions caused by the losses. The cumulative unresolved feelings created a massive preoccupation from which I made one horrible business decision after another. I had no alternative but to declare bankruptcy. Having been socialized to be the provider, the bankruptcy caused me to feel like the biggest “loser” on the planet.

’89 Marie—Marie, my girlfriend’s mother, died. We had become quite close. I loved the way she asked me how I was doing and then really listened to my answer. By the time Marie died, I had begun working at the Grief Recovery Institute. More important, I had completed my relationship to the pain caused by the prior loss experiences in my life. My personal completions allowed two different things to occur. First, I was as complete as I knew how to be with Marie while she was still alive. Second, I was really affected by her death. Having completed earlier relationships, my heart was open to new ones. Being open means that painful things hurt. That same openness had allowed me to be more loving. Sadness being the normal and healthy reaction to loss, Marie’s death hurt my heart.

’92 Harry—Harry, my girlfriend’s father, died. He and I had become very close after his wife, Marie, died. We spent countless hours on the couch at his house or my house watching every possible sporting event. He was eighty-seven, but he had an amazingly critical eye for all the details of each sport. He also had a wealth of knowledge of sporting events from before I was born. It was often like a fun history lesson for me. As fate would have it, Harry died just a few days before the Super Bowl. There was a very empty seat on my couch on Super Bowl Sunday.

’93 Dog Zoey—Our dog Zoey died. She was a 100-pound lap dog. (If a 100-pound dog wants to sit on your lap, you don’t argue with her.) She was zany and wonderful, and as with many relationships with pets, mine with her was unconditionally loving. She had been with my girlfriend and her daughter since she was a puppy. When I moved in, she adopted me and trained me. When she got cancer, we tried everything, but to no avail. As I arrived home each evening shortly after she had died, my heart would fall to my feet as soon as the garage door started up. Those moments when I remembered that Zoey would not be at the top of the stairs to greet me were among the most painful I have experienced.

’93 Mom—The day before Thanksgiving, suddenly and unexpectedly, my mother died. Let me try to describe for you what I experienced in the moments after I was told that she had died. I had walked into my office around 11:00 A.M., having just finished an early morning round of golf. As I walked through the office doorway, my assistant stood up and said, “Russell, I have terrible news, your mother has died!” I felt as if I had been hit in the chest with enough force to knock me down—my knees buckled and I started crying. As my legs sagged, my assistant and another friend surrounded me and held me up. I fell into their arms and sobbed and sobbed.

WHAT GOES ON THE LOSS HISTORY GRAPH

Since most of us relate the words grief and loss primarily to death and perhaps to divorce, let’s establish which human experiences come under the heading of grief. Here is the most helpful definition we use: Grief is the conflicting group of human emotions caused by an end to or change in a familiar pattern of behavior. Thus, any changes in relationships to people, places or events can cause the conflicting feelings we call grief.

Look at how many other loss events are also covered by this definition. Think about moving. When we move, every single familiar pattern may change. Where we live, where we work, and who we regularly see all change. Major financial changes, positive or negative, create massive changes in our familiar patterns. Major changes in bodily functions or abilities can have enormous grief consequences. Losing the use of limbs or eyesight or a condition like diabetes or kidney failure automatically alters familiar patterns. Strokes and heart attacks often affect how and when we exercise and what and when we eat. Menopause can cause huge feelings of loss for women as well as for their mates. Divorce is somewhat obvious when it is our own. We are also affected by the divorce of anyone we are close to—parent, child, sibling, or other.

Childhood issues of mistreatment—physical, sexual, or emotional—often set up patterns wherein positive interactions are sabotaged because they are not as “familiar” as negative interactions.

Many life experiences fit our definition of grief. Almost anything that has affected you negatively is a grieving experience for you. When you read John’s and Russell’s Loss History Graphs, you got some idea of which life events are losses. Generally speaking, if you think something was a loss, put it on your graph. You can’t really make a mistake in this exercise.

THIRD HOMEWORK ASSIGNMENT: PREPARING YOUR LOSS HISTORY GRAPH

With all of the preambles out of the way, it is time to begin. We will give you (both partners and those working alone) the instructions for the Loss History Graph exercise just as we do in our seminars.

1: The entire exercise should not take you more than an hour. You may experience a wide range of emotional responses as the result of doing the Loss History Graph. Or you may have little or no emotional response. That is perfectly okay, do not be alarmed. Have a box of tissues handy. If you have an emotional reaction, let it be okay with you.

2: The writing part of the exercise is nonverbal. It is best done alone and in silence.

3: Get a pen or pencil and a piece of blank paper, at least the size of typing paper or standard notebook paper (8½" × 11"); legal-size paper (8½" × 14") is even better. Place the paper horizontally on your desk or table.

4: Draw a straight line across the center of the page. Then divide your line into four equal parts, marking the sections lightly with a pencil. This will give you reference points for plotting dates.

5: For example, if you are fifty years old, at the halfway point you were twenty-five. Write the year of your birth at the left end of the line. Write the current date on the right end of the line. Then plot your dawn of conscious memory, or earliest recollection, whether you perceive it as a loss or not, and mark it just after the year you were born.

6: Our examples began with our earliest conscious memory. If you think hard, you’ll find that your first recollection will most likely fall between ages two and five, probably closer to five. It may be good or bad, happy or sad; it may be an event, an experience, an object, or a place. One of the easiest ways to establish an effective dawn-of-conscious-memory date is to remember something about your first house. Do not spend an inordinate amount of time establishing your dawn-of-conscious-memory date. It is merely a starting point.

7: You do not need to get the dates exactly right. We are much more interested in your emotional response to your losses.

8: Now take a few moments and ask yourself, “What is the most painful, life-limiting loss I have ever experienced?”

All losses are experienced at 100 percent intensity when they occur. As we reflect, we recognize that some losses have had a greater impact on us than others. We have referred to the fact that relationships are composed of both time and intensity. Here is what we mean.

Russell had gone to the same dry cleaner, twice a week, for ten years. The same lady took his shirts and his money each time. He didn’t know her name, so he referred to her as “the lady.” One day when Russell went to pick up his shirts, a man came and took care of him. Russell said, “Where’s the lady?” “Oh, she died.” Russell felt a sense of sadness even though he had not known her name, nor anything about her. That relationship, although of many years’ duration, had almost no intensity.

Russell was engaged to a young woman in 1964. This passionate relationship lasted only three months. When the romance crashed and burned, the two of them were not on good terms. He never spoke to her again. Thirty-two years later, Russell got a call from a mutual friend saying that she had died. This news had a powerful impact on him. The relationship, while short, had had tremendous emotional intensity.

1: Identify your most painful loss. Find the approximate date point on your horizontal line and draw a vertical line downward to the bottom of the page. Make a notation of what the loss was: “Mom died,” “Child died,” “Divorce.” You don’t have to spend too much time writing out at length each separate grieving experience, as we did in our examples. Just make simple notes of words or phrases that will remind you of the loss.

2: After establishing and plotting your most painful loss experience, let your mind go back to your earliest memories and start marking down the loss events you remember. Use the length of the vertical line to establish the relative degree of intensity of the loss. Always make short notes so you will be able to recall what the loss was; for example, “Dog died,” or, “Lost business.”

Occasionally, you may realize that you have had both positive and negative responses to the same experiences. This is totally normal. For many people, their wedding day is simultaneously the most exciting of all days while also representing a “loss of freedom.” The birth of a child can be exhilarating, on the one hand, and terrifying, on the other, as the parents take on new responsibilities. For the purposes of this exercise, however, we are focusing on the sad, negative, or painful aspects of these events. Grievers will often try to deal only with the positive side, so as to avoid the painful. That’s one of the reasons you are using this book, so even if it seems uncomfortable, please stay with the loss perspective only.

If you find that a half-hour has gone by and all you have plotted is your dawn of conscious memory and one other loss, then take a break. Sometimes we try a little too hard and get stuck. Look back at John’s and Russell’s graphs. Their graphs will remind you of some of your losses.

It is not at all unnatural to sense some resistance in yourself. Remember, persistence will pay off in the long run. Our experience has shown us that most people over the age of fourteen have at least five losses to plot. For adults, the average is between ten and fifteen loss experiences.

Don’t try to get this “right.” Just be honest. There are no grades given for this work, and no one’s approval is required. Abandon yourself to the exercise, and you will receive benefit directly proportional to the amount you put into it. But first, and now, you must begin!

LEARNING FROM YOUR LOSS HISTORY GRAPH

Congratulations on finishing your graph!

The story of your life can be an eye-opening experience. It is imperative that you look at your losses to discover what misinformation you were taught directly or absorbed indirectly. It is equally essential that you not judge, evaluate, or criticize yourself for what you were shown or for interpretations you made.

Your first commitment in this regard is to be gentle with yourself about the discoveries you make. It can also be helpful to suspend judgment and criticism of those who taught you any incorrect ideas. Don’t worry, you will have ample opportunity later to complete any thoughts and feelings about the sources of misinformation.

Having finished the graph, it is now time to examine it and see what you can learn. From your dawn of conscious memory onward, you may be able to get some very clear pictures about what you were influenced to believe. For those of you working with partners, you will soon see how many parallels there usually are between grieving people. In our seminars and outreach programs, people are often amazed at the losses and attitudes they have in common. While there are many parallels, we are still individuals. Scientists tell us that no two snowflakes, crystals, or grains of sand are alike, but they are made of the same ingredients. People are also unique. This exercise helps illustrate our human similarities and differences.

For those of you working alone, you might notice that some of your losses and attitudes are similar to some of John’s and Russell’s.

Begin by reaffirming your commitments to total honesty, absolute confidentiality, and the uniqueness of your individual recovery. As always, meet in a private place where you will not feel uncomfortable if you cry. Have tissues handy.

This meeting marks a change in how you will proceed. These new guidelines will carry you through the balance of your meetings. Read them very carefully. Successful completion hinges on following these instructions.

Working with a partner does have benefits. One is the ability to verbalize what you have written. In order for this exercise to have the maximum value, we will give you some very strong guidelines, which we have developed over twenty years. We suggest that you adhere to them.

Make sure you bring your Loss History Graph and the two lists—on misinformation, and short-term energy-relieving behaviors—that you’ve already discussed.

Instructions for the Listening Partner

- Sit a reasonable distance away. Avoid a sense of being in your partner’s face or smothering him or her.

- As the listening partner, you may laugh or cry, if appropriate, but you may not talk!

- Do not touch your partner. Touch usually stops feelings.

- Remember the image of being a heart with ears. Do your best to stay in the moment and really listen to your partner’s story.

Instructions for the Talking Partner

- Try to tell your loss history graph in half an hour or less. This is not a rigid rule, but be careful not to turn the entire meeting into a long monologue, which would have no value for you.

- If you cry, try to keep talking while you cry. Push the words up and out, rather than swallowing them. People tend to choke off feelings in their throat.

- When you finish your graph, ask your partner for a hug (assuming you’ve made hugs safe).

- After getting your hug, take a few minutes to talk again about the misinformation you learned following your losses as well as the short-term energy-relieving behaviors you may have participated in. This is an ideal opportunity to see the connection between your beliefs and the limits they may have put on your recovery.

Take a little break, and then let your partner do his or her graph.

Make plans for your next meeting.

For Those Working Alone

Since you are working alone, you may find it effective to use John’s and Russell’s Loss History Graphs as your silent partner. Reread theirs, then look at yours. Notice the similarities and the differences. Once again, look at your STERBs. See if you notice any connection between your short-term relievers and your losses. Look at your lists of myths and beliefs to see whether they connect to the losses you have graphed.