First semester at Mason Gross at Rutgers University in New Brunswick. Four 8:10 a.m. classes, commuting from home in Newark. Yes, I live in Newark, Brick City, bad reputation, scary place of children gunned down in a schoolyard and a riot/rebellion no one ever forgets. Even now, visiting New Yorkers expect wisps of smoke to rise from Newark’s rubble. Mine is the Newark of charismatic men: fierce Amiri Baraka and lovable Cory Booker—Newark, where everyone on the street—nearly everyone—is black, brown, or tawny. This scares some people.

My North Newark neighborhood isn’t scary, just nice houses, nice yards, and nice neighbors, families gay, straight, black, white, Latino (Puerto Rican, Dominican), and a few Asian (Southern and Eastern). I know most of my neighbors and chat with them about their dogs and what day the city will be picking up leaves.

My block of my street is a little paradise, interrupted only occasionally by a mugging or a burglary or a house alarm (mine) sounding off by mistake. The biggest news was a neighbor in one of the huge corner houses who was posing as a cosmetic surgeon in Manhattan and killed a patient who came into his hands for a cut-rate nose job. He buried her under the steps of his carriage house and ran off to Costa Rica.

Down the hill a couple of blocks is a commercial street, Mt. Prospect Avenue, with a pharmacy, restaurants, a health center, a couple of liquor stores, and shops where you can send money to Latin America and have documents notarized. At a deli takeout counter, the clerk asked about my origins, first in English. I said I’m from California. He switched to Spanish and lowered his voice: “Dominicana? Cubana?” I do indeed fit right in.

Giddily as if off to summer camp, sprightly in the early light, I would set off to Mason Gross from my quiet block at 6:30 a.m., portfolio under one arm, art box in hand. I walked across Branch Brook Park, still late-summer chromium oxide green, later, burnt-umber bare, then, in the spring, the pale green of kitchens in the 1950s.

To get from my house to Mason Gross, I joined New Jersey’s national pastime of commuting. At first I thought of my commute as simply getting to art school, as traversing the space between Newark and New Brunswick. I thought of it, no, I hardly thought of it at all, beyond calculating the time it would consume. Over time I came to cherish commuting as immersion in my polychromatic state of classes and nations. Soon I was swimming like a little brown anchovy in a school of thousands of little anchovy-commuters, happily unremarkable, yet singular with my portfolio and art box. Don’t ask me to resolve the contradiction.

The everydayness of my fellow commuters left little impression. Invariably someone waiting around the light rail station was complaining into a phone that it’s “muy caliente” or “muy frio” or other observations as banal in Spanish as in English. But there were always sparklers, people I’d never see elsewhere or never see again anywhere—the jewels of my commute.

Sitting in front of me on Newark light rail one afternoon were a couple of kids—early twenties or so—listening to music, bumping around in their seats, and talking loud, just exuberant. She was beautiful and spirited, he kind of ordinary to look at. He had the music, but he shared an earbud with her, two heads on one iPod.

As she danced in her seat, he did something amazing. He played the subway car partition like a conga drum:

DeepDEEP slap stop DeepDEEP slap stop

DeepDEEP slap Deep DEEP slap stop

DeepDEEP slap stop DeepDEEP slap stop

DeepDEEP slap stop DeepDEEP slap stop

DeepDEEP slap stop

DeepDEEP slap stop DeepDEEP slap stop

DeepDEEP slap stop

DeepDEEP slap stop DeepDEEP slap stop

DeepDEEP slap stop

DeepDEEP slap stop DeepDEEP slap stop

DeepDEEP slap stop

He pulsated a salsa rhythm on a vertical plastic divider. Totally awesome! I was ready for all of us passengers to jump up and boogie down the aisle. I wouldn’t have led off dancing, but I definitely would have joined in. What joy in our white and black metal tube of light rail beside Branch Brook Park, a carnival parade on a workday, an outbreak of brotherly love to a salsa beat. Strangers waving their arms and shaking their booties to the music, grinning and singing and looking straight in the eyes of their comrades in commute. But when the pretty girl started clapping her hands to the music, he of the beat shushed her. No dancing in the Newark light rail that afternoon.

The couple had a third-wheel friend across the aisle, a heavyset young woman their age without the couple’s brio. No music, no style. To my eye, the trio was dressed like everyday Newark kids, the women in kind of tight, fashionable clothes, the fellow in the ordinary baggy stuff of the streets. Nothing distinguished or classy, or so I thought. I misjudged them. At one point they staked their place in the cultural terrain, agreeing they wouldn’t be caught dead in Newark’s “ghetto bars.” No. They go to Irvington. The fellow imitated Irvington’s middle-class (?) white (?) talk, all “dude” this and “dude” that, with “bro” mispronounced in that way of dudes who don’t know it’s short for “brother” and ought to sound like “bruh.” Much to see and hear on public transportation.

IN NEWARK PENN Station in the morning, we’d bolt up escalators (they nearly always work), many heading to track 1 to New York City, others, like me, to track 4 for the Northeast Corridor train going west (meaning south) toward New Brunswick and Trenton. In the track 4 waiting room my fellow commuters massed shoulder to shoulder on long, facing benches, a few traditionalists reading newspapers and books, many, many more bending their heads into their iPods and cell phones. At first I couldn’t figure out where the droning came from. Other travelers knew better. They kept to their phones and ignored the evangelist, a Jamaican according to his accent, insinuating Revelation at us captives.

With time my irritation subsided and the evangelist became just another character, just another star in the drama of New Jersey Transit. He did eventually depart, and after he had departed, I missed him as this jewel of my New Jersey commute, with its rainbow of voices from the islands of the Caribbean Sea, English and Haitian Creole and Spanish, and Hindi from the East.

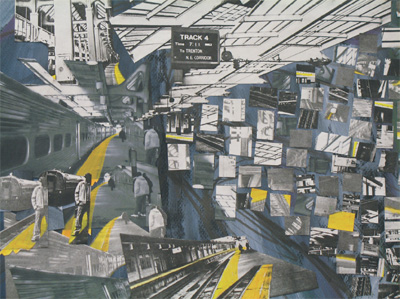

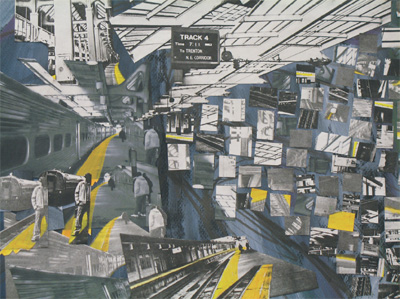

I passed through Newark Penn Station almost every day. It has moving sky above the open girders, clouds, and, if you stand aside, the windows of Newark’s skyscrapers reflecting clouds and sun. An overload of information on trains and things you can buy and Broadway shows and insurance and travel to other, sunnier places, even Massachusetts. Newark Penn Station has its own perspective, its own light and shadow, its own movement in a rainbow of gray, yet within its overall colorlessness, a beguiling combination of a million yellow-grays that have no name. People all nearby and down the track. I made piece after piece of art on the theme of Newark Penn Station.

Newark Penn Station, 2006, paper collage, approx. 18" × 24"

Newark Penn Station sits between downtown and the northwest edge of the Ironbound section, which used to be the city’s poorest, the low-lying East Ward neighborhood of industry bounded by the railroad tracks giving it its name. The Ironbound was always a mixed place of working-class people, an entire neighborhood on the wrong side of every track. Nowadays the Ironbound takes its character, at least that part of its character considered tourist-worthy, from Portuguese, Brazilians, and people from Central and South America. The Ironbound’s current fame, such as it is, rests on places to eat too much and to watch soccer games as you drink. Ferry Street’s a great place for spontaneous street parades of honking cars and giddy people when your Latin American country wins a soccer game.

The Ironbound’s overall complexion tends toward swarthy, its sartorial character unpretentious. One day on my way to Newark Penn Station on Ferry Street, I encountered a young man who complimented me on my hair. (People like my gray hair.) His T-shirt rendered me speechless. Across his chest was, “Fuck you, you fucking fuck.” Three fucks on one piece of clothing. To my mute astonishment, he responded,

Have a blessed day.

EVER OBSERVANT OF my unsurpassed (though chronically underappreciated) state, I watched it from the window of my Northeast Corridor train. Yes, New Jersey is splendid, its crummy cities testifying to lost industrial might, its Atlantic beaches, the little houses with long narrow backyards where people garden and, in good weather and weekends, eat and drink under leafy arbors replicating the old country. I would sit in the train on the east side, passing the time and temperature on the Budweiser factory, Elizabeth’s hulking, slot-windowed jail, a gigantic new apartment building under construction by the Rahway station, the accounting companies’ behemoths at Metropark, where even Amtrak stops occasionally, and the Raritan River at New Brunswick.

The Raritan complicates relations between the Rutgers campuses in Newark and New Brunswick. Rutgers was founded as Queens College in New Brunswick in 1766, before the American Revolution, “on the banks of the old Raritan,” as in the university’s official song. The Raritan River runs through (then) bucolic (now suburban) central Jersey, emptying into Sandy Hook Bay down by Perth Amboy. The University of Newark joined Rutgers in 1946, becoming Rutgers University–Newark, an urban campus near the banks of the Passaic River, the industrial north Jersey Passaic River that empties into Newark Bay beside the Hackensack River coming from Secaucus, the warehouse capital of the world. You could say that these two rivers, the grubby, industrial Passaic River and the picturesque, colonial Raritan River, stand for the contrasts, the tensions, between the haughty flagship campus in New Brunswick and the scrappy urban one in Newark. Hence Newark’s river-identified colonial resentment. I was attached at both ends.

NEWARK PENN STATION pivoted me between Newark’s light rail and my train to Mason Gross in New Brunswick. But if I wanted to go to New York City to visit The Art World, I’d often take a New Jersey Transit train from the other Newark train station, Broad Street, or, as Newark old-timers call it, Lackawanna Station.

Walking up to the 27’s bus stop on Mt. Prospect Avenue on a sunny midmorning, I heard a familiar sound from my long ago, my very, very long ago. An alto recorder. Now there was a sound of my nostalgia. When I was in high school in Oakland, my mother and I played recorders with an amateur early music group. I recognized the sound on Mt. Prospect Avenue without being able to make out the melody. As it ended, I was about to thank the musician, to gush about recorders and say how much I enjoyed his music. But his lurch to the right gave me pause. Was he drunk? Was he high? Recorder or no, I couldn’t engage a man so obviously impaired.

The musician staggered a few more paces along the wrought-iron fence of Bethel Evangelical Church, where a worker was mowing the grass inside the fence. On Mt. Prospect Avenue, the musician was African American, the Bethel Evangelical Church lawn mower Latino. The recorder player faced the mower, looked at him sweetly, and resumed playing in the mower’s honor. This time I recognized the air: the prelude to La Traviata. La Traviata on Mt. Prospect Avenue in Newark, played on a recorder. A drunken musician serenading a man mowing the lawn on the other side of the wrought-iron fence in front of the Bethel Evangelical Church.

That was the first time I’d heard anyone playing a recorder in Newark. But in the late afternoon of the same day, as a party of us architecturally minded, upright citizens were touring the newly empty, faded yellow-ochre Central Graphic Arts Building4 on McCarter Highway, the son of one of our party pulled out his soprano recorder and started playing while we were on the roof. Two Newark recorders in one day. But only one in my commute.

I’M STILL GRATEFUL for public transportation to New Brunswick, thankful for a visually interesting state of colorful congestion and junkiness and its characteristic sounds—Revelation, salsa drumming, La Traviata played on an alto recorder, and, leaving every stop, the voice of then Mayor Cory Booker thanking me and all my fellow travelers for riding Newark light rail.

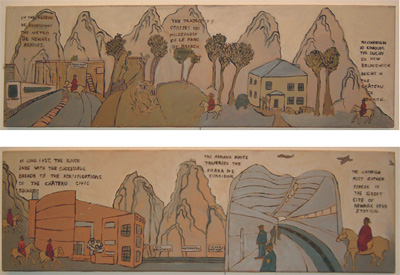

Faux Chinese Scroll, 2006, oil on canvas in two pieces, each 12" × 48"

For my final project in painting class I depicted my commute from home to Mason Gross after an art history assignment had taken me to the Metropolitan Museum for a report on southern Song Chinese painting. My final painting project reworked that assignment, adopting the style of an ancient Chinese scroll, reading right to left and painted in the scrolls’ warm, desaturated colors. I depicted myself as a mounted Chinese warrior in a gorgeous red coat, repeated in the style of simultaneous narration that I had just discovered in Islamic art in art history class. Chinese-warrior-me repeated seven times, starting with leaving my house, crossing Branch Brook Park to the light rail station, to Newark Penn Station, my New Jersey Transit Northeast Corridor line (complete with lumpy Chinese mountains), and over to Civic Square Building on Livingston Avenue in New Brunswick. Traveling on public transportation meant I couldn’t carry my piece on the train as it should have been made, twelve inches high and eight feet long. So it’s in two pieces, with what should be the right side above the left.

My Faux Chinese Scroll commemorated my emblematic experience in art school: my commute and my affection for New Jersey camaraderie. A commute anchovy in what I might call Du Boisian oneness with my fellow anchovy-commuters.