How could I possibly learn to paint like that—the composition, the figures, the detail, the touch, the colors? An impossible chasm of expertise separated The Fortune Teller from my poor inadept hand, a gulf not only of centuries, but also of skill and sophistication. At the painting marathon at the Studio School a couple of years earlier, I had bemoaned the amateurish look of a painting I had concentrated on for hours, maybe for days. My teacher, sympathetic but factual, retorted,

You are an amateur!

True. All too true.

Happily for me, artists had long ago turned to transcription as means to further their skills through close study of the work of others. This kind of painstaking labor is no longer common in art education. Still, beginning and established artists use transcription as boot camp and as an occasional return to the basics. I could concentrate on the visual in this way, via the work of others.

By gridding another artist’s painting into squares and copying the image onto my own canvas, I could follow and unlock another painter’s secrets, from composition and line to color, right down to denser or thinner paint. This was no new invention. Transcribing masterpieces used to be integral to art education. Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres copied—no, transcribed—old master paintings in the Louvre, newly opened as a museum in his youth. Henri Matisse transcribed still lifes by Jean Chardin.

Transcription would take me into the details of someone else’s painting, centimeter by centimeter. How does this line connect to that one? How much cadmium red inflects that cobalt blue? How close is this figure to that one, and do they overlap to create the illusion of depth? Is paint laid down thickly in impasto or thinned practically into ink? Copying existing works would show me new ways of seeing and applying color. From the Studio School painting marathon, I already knew that painters use tricks like putting a spot of white in the pupil of the eye to convey liveliness and making a muddy mixture of colors for an undecipherable facial shadow. A start.

I would need to learn how to paint people so that bodies looked alive. Face and figure need expression flowing into the body’s parts to make them occupy a particular space. They need movement to enliven their poses. Composition would also need a play of light and shadow, perspective, the illusion of space and volume, and the possibility of narrative, of a before and after the scene, all this without slavish realism.

For my purposes, I would also have to learn how to depict dark skin, where La Tour’s painting and virtually all the painting in virtually all the museums I’d ever visited wouldn’t help. This is not just a matter of using brown paint, because if I didn’t use additional colors, reds and yellows, even blues and greens, the brown would look flat and dead. And I would need to capture the reflectiveness of dark skin through contrast. This would be awfully hard for me, because painting dark skin and its reflectiveness weren’t taught in my school. I had Mentor Bill to help me with this, but I never managed it as an art student. However, I had encountered transcription at the Studio School.

The Studio School marathon had included an assignment transcribing a Rembrandt drawing. I had continued the exercise the summer afterward with a book of Rembrandt’s drawings I pulled off my shelf in the Adirondacks. I had bought the book years earlier and now reread the text. It talked about Rembrandt’s life and fortunes, his preferred subjects, including himself and his wife, Saskia, and his most famous paintings, The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp and The Night Watch. Before that moment, I hadn’t missed information I now sought, but found lacking: how big were these drawings? And, of even deeper import, what kind of paper, which mark-making tools did Rembrandt use? As I prepared to copy Rembrandt’s drawings, these were my questions. I hadn’t wondered about his process back when I bought the book.

I figure the drawings I copied were made on textured cold press paper with tooth, now darkened, in what looks like walnut ink but is probably black India ink that has faded. I learned later that Rembrandt also drew in red, black, and white chalk, sometimes along with ink and pencil. The 6B pencil I used makes a very different mark from a quill pen. By varying my pressure and using the point or the side of the pencil, I could evoke Rembrandt’s line and washes, though, alas, not the sureness of his hand.

Even in pencil, it was a slow process of contented concentration. It’s not the same as when I make my own work, though both processes demand submersion in the image and a kind of searching. The search in my own original work feels more open, like standing on Hurricane Mountain in the Adirondacks and looking all around for the next peak to attempt—or, more likely, how in the hell to get back down. Transcription’s gaze hones in closely on an existing image that may hold as many secrets as the mountains. Keeping to the metaphor of mountain climbing, transcription focused me on the path immediately before me, its secrets already there but held within.

That contented concentration is what I love about making art. I don’t call it fun. My non-artist friends would invariably ask about art school, was I having fun? True, art can feel like play, can actually be play. But I’d say fun is too frivolous an amusement-park word for the contentment, the concentration, the peace of mind I experience when I draw or paint, even when the work isn’t going well or feels unfinished. My friends in California would say I was in the zone. Wherever it was or is, time passes without remark; hunger disappears; fatigue only pounces once drawing ends.

IF TRANSCRIPTION IS to reveal its lessons, it’s a meticulous process that takes a lot of time, which I did not have in painting class. Though La Tour’s Fortune Teller measures only about 40" × 46", it was far too detailed with too many figures for me to transcribe in one semester, even if that were all I planned to paint. Perhaps with more than a few months before me, I would have attempted it. But probably not, for more than just skill separates me from Georges de La Tour. His painting was too much a piece of its seventeenth-century times, too subtle, too close to museum masterworks for me to replicate.

I had many reasons to hesitate before the La Tour painting that intrigued me: the limitations of my undergraduate skills, my times, my in-between-ness as an ambitious student and as a black artist coming out of an invisible art history. Already I could hear the expectation, an unspoken command, that a black artist’s subject must always be blackness, that white art history was art history, and a black artist’s relation to it could only be confrontational, even though no one was saying this kind of thing to me in so many words. The judgments spoke through the air, wafting toward me unbidden, issuing from mouths I could not see. Even though I always told myself that other people’s expectations wouldn’t hinder me, disembodied expectations gave me pause.

So there I was, trying to learn to paint people, not just white people, avoiding the trap of too much realism, but wanting to capture likeness and a certain kind of unconventional beauty—beauty as a barbed concept but the truest word we have for excellence. A further conversation with Teacher Stephen brought him around to my choice of artists to transcribe. I leaned toward offbeat images that held my eye with unexpectedness. My choices, based on the formal qualities of their work, were two twentieth-century painters now in art history, the German Max Beckmann and the American Alice Neel. In Neel’s case, there was the draw of her ballsy, nude self-portrait as an old woman and a portrait of another woman painter, Faith Ringgold, whose work as an artist and activist addresses injustices in American society. My attachment to them as women and as older women artists was obvious. There was also, for both Beckmann and Neel, the lure of depicting oneself psychologically in time and place.

I FELL HARD for Alice Neel’s unprettified, humorous, naked self-portrait at age eighty. I thought the painting was generous in size at 53" × 40", though in light of contemporary art’s prevailing huge dimensions, that now seems a modest scale. The work’s courage spoke to me first, for this was back when I was conventional-minded enough to fault Neel’s draftsmanship. I could never paint myself naked—I cringe just mentioning such a thing, and I could not even have done it in my youth when American history and my personal upbringing dressed me modestly. I admired Alice Neel’s spunk, which reminds me of You or I (2005), the Austrian painter Maria Lassnig’s self-portrait, also naked in her maturity. Neel ordinarily painted other people as she painted herself, naked. In its unflinching depiction of an old female body, her self-portrait is also an anomaly within the long tradition of artist’s self-portraits, usually male, usually young, seldom sagging in body or face.

Neel was a leftist early on and never discarded her strong political convictions. She painted a union organizer reading the Communist Daily Worker, showing its name, hammer and sickle logo, and the headline “Steel, Coal Strikes . . .” clearly legible beneath his fists. Living and loving in Greenwich Village and working on the WPA in 1933, she portrayed an eccentric writer friend, Joe Gould, undressed, with five uncircumcised penises, three in the center on his own torso, one each on torsos on the sides of the frame. In the 1940s, ’50s, and ’60s, she painted her working-class Latino neighbors in Spanish Harlem when white artists seldom painted subjects of color. She painted naked women with big, pregnant bellies, children, herself and her lovers, always with genitals strikingly resolved. Sometimes her backgrounds show an interior, but vigorous color more often amplified the emotional impact of portraits that got bigger as time passed, without approaching the massive scale of her Abstract Expressionist contemporaries.

After decades of obscurity, Neel started being recognized in the 1970s. She began painting art-world notables like Andy Warhol and Frank O’Hara that put her in proximity of celebrities. These works came at the same time that feminist art historians and critics were at last making women artists visible through acknowledgment in print, as in Linda Nochlin’s groundbreaking 1971 ARTnews article, “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?” and in groups like Women in the Arts and Women’s Caucus for Art, where Neel showed her work alongside Faith Ringgold’s. Neel and Ringgold became comrades marching together in picket lines protesting art-world discrimination and the Vietnam War.

Neel’s 1974 Whitney retrospective signaled her arrival as a major artist. I was struck that after so many years keeping at her art, it took the Whitney retrospective to justify her work in her own eyes. “The show finally convinced me that I had a perfect right to paint,” she remarked at the time. Reading that statement, I thought it was so like a woman. She was seventy-four years old. So like a woman that it took until then.

I also chose Alice Neel because I felt I painted a little like her, or, rather, if I painted longer and better, I’d hope to paint like her. The way she painted unconventional subjects with a drawing hand free from anatomical punctiliousness made her portraits psychologically acute. Her non-naturalistic color, her expressive line, and her flattened pictorial surface made her my hero. My plan to steal her secrets through transcription settled on her forthright painting of Faith Ringgold.

I had known Faith Ringgold slightly for years and had admired her extraordinary range of work—much on historical and art-historical themes—before attempting the transcription of Alice Neel’s 1976 portrait. Ringgold writes as well as paints, and she was the first object of my love for artists who make books. Although a generation younger than Neel, Ringgold was still one of the multitude of women artists whose work was ignored for a long time.

I once asked the painter Pat Steir how she kept working in those many decades of sexist obscurity. How did you persist, I asked. She answered,

Sheer spite!

Painter Howardena Pindell has said she kept working to deprive The Art World the satisfaction of shutting her down. Ringgold kept going by making art that addressed her own personal questions as a woman artist and as a black woman artist. Those questions aren’t the same, because racism isn’t the same as sexism. It comes on top of sexism and can run off in different directions. Ringgold’s work answered in words as well as images, in her own original way.

Ringgold began her painting career protesting American white supremacy and patriarchy. It was this work, she told me, that damned her in The Art World as an activist rather than a painter and her work as propaganda rather than art. In the 1980s she began working on fabric in collaboration with her mother, a fashion designer, creating a series of painted and collaged story quilts that combined text and images. These quintessentially postmodern works create fictional art-historical narratives in which historical figures like Matisse (one of Ringgold’s favorite artists) appear beside invented characters. Ringgold was making the free-spirited historical fictions that had drawn me to art in the first place.

One of the twelve story quilts of The French Connection (1990–1997), Dancing at the Louvre, depicts Willia Marie Simone, Ringgold’s fictional African American protagonist, in Paris in her twenties. Willia Marie becomes a muse and model to Matisse and Picasso and an artist herself. Living a life in Paris of extravagant fullness, she speaks for Ringgold and many other women artists:

My art is my freedom to say what I please, n’importe what color you are, you can do what you want avec ton art.

Out of necessity, she said, Ringgold turned to writing, after complaining of invisibility to her activist lawyer friend Florynce Kennedy.

Kennedy responded, Write your own damned self.

Ringgold wrote Tar Beach, a Caldecott Honor Book, based on her story quilt of the same title, and an autobiography, We Flew Over the Bridge, describing how she makes her art—more than ninety-five quilts and hundreds of other artworks, including sculpture and public installations like the Flying Home Harlem Heroes and Heroines mosaics in the 125th Street station of the New York City subway. I admired her work and her grit at keeping at it over the long haul. Here came inspiration.

In her determination to paint and write her own damned self, Ringgold shared Neel’s dedication to her work across decades of disregard. Having painted so long in obscurity, both worked in their own ways, heedless of Art World fashions. They had freed themselves and their work from The Art World’s gaze and persisted. They were seeing their art through their own eyes, not the eyes of others. By now, at last, Neel and Ringgold have won their share of Art World recognition.

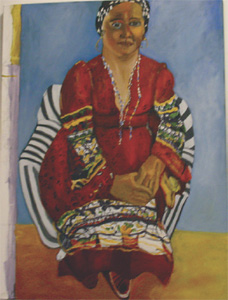

My Neel’s Ringgold, 2007, oil on canvas, approx. 24" × 18"

Neel’s Ringgold portrait is a strong image dominated by the cadmium red of the dress against a cobalt-blue and yellow-ochre background. Neel wanted to paint Ringgold naked, but Ringgold said no, perhaps out of the same black-woman aversion that made me recoil from depicting myself unclothed. Ringgold’s refusal of nudity yields a bounty of pattern in the dress, necklaces, and hair decoration against the blue-and-white-striped chair that appears in many of Neel’s portraits. This is a thoroughly feminist work that started, and I do mean only started, teaching me how to enliven a portrait and paint dark skin.

Ringgold told me that after Neel’s death, she copied Neel’s naked self-portrait, adding text that affectionately recalled their friendship.

IN THE MID-TWENTIETH-CENTURY era of Abstract Expressionism, Alice Neel was an outsider whose raw, expressive brushwork and sensitive drawing put her in the company of the German artists of the Neue Sachlichkeit, or “New Objectivity,” of the 1920s. Like the German painters I was drawn to, she captured the tenor of her times, often with an edge of satirical social realism, though her work never approached the bitterness of George Grosz and Otto Dix or the searing social protest of Käthe Kollwitz. Neel called her portraits “writing history,” saying, “I paint my time using the people as evidence,” an attitude that spoke to the historian in me. I count her as an expressionist, for her personal style shared the essential spirit of German expressionism.

In art school, I came back to German expressionism via Alice Neel, though I had first encountered it in an exhibition of work about Potsdamer Platz at the Neue Nationalgalerie when Glenn and I were on sabbatical in Berlin. The exhibition showcased this crossroads that had been under the Berlin Wall from 1962 to 1989 and was being aggressively redeveloped after the wall came down. The exhibition centered on Ernst Ludwig Kirchner’s Potsdamer Platz (1914). On my first view of Kirchner’s painting, I thought,

This stuff is really ugly.

Vertiginous perspective, skinny women with green faces and vacant eyes, crazy color, slapdash brushwork. But the more I saw of Kirchner and, especially, the postwar painters of the New Objectivity, the more they spoke to me. Influenced by art from Oceania and Africa newly arriving in Europe, early-twentieth-century German expressionists made mordant images of postwar German hypocrisy and rejected the naturalism of pretty prewar paintings that I also could not like. I admired this work’s critical edge as the perfect antithesis of work like Norman Rockwell’s, the black romantics’, and the Adirondack plein air painters’. Expressionists rejected sentimentality. And bravo to that.

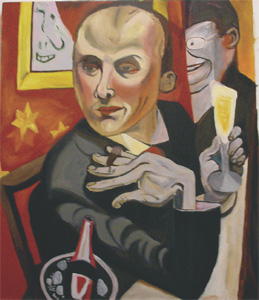

Here was the style I was coming to prefer, figurative but untethered from slavish realism. Art with an edge of unrest. I chose to transcribe two of the self-deprecating self-portraits of one of the Potsdamer Platz artists, Max Beckmann. Beckmann made large works with multiple figures depicting scenes from mythology before and after a series of sardonic self-portraits. It was not only the life of the painter that attracted me, as with Neel and Ringgold. There was a bit more. Beckmann painted Self-Portrait with Champagne Glass in 1919, a year of tumult I had written about at length in Standing at Armageddon: The United States 1877–1919. So, yes, once again, something of history came along with the art I was drawn to.

Beckmann was an artistic prodigy from Leipzig in Saxony in eastern Germany who spent time in France and Italy in the very early years of the twentieth century. There he made huge paintings and fancied himself the German Delacroix. From the beginning he painted self-portraits, early inspired by cubism, later more painterly, all expressing his intensely individual focus. He holds a horn or saxophone, wears a red scarf or bowler hat, or masquerades as a sailor, an acrobat, or the medical orderly he had been in the First World War before a nervous breakdown.

Beckmann flourished after the war until Hitler’s National Socialists designated him a “degenerate” artist in 1937 and ruined him in Germany. The Nazis confiscated six hundred museum works (he had made six hundred paintings of museum quality!) and sent him into several unhappy years of exile in the Netherlands. In 1947, with the help of his dealer and the head of the Saint Louis Art Museum, he immigrated to the United States to fill in temporarily for Philip Guston at Washington University in Saint Louis. Beckmann died of a heart attack on the corner of West 61st Street and Central Park West in Manhattan in 1950, as his work was being featured in the German Pavilion of the Venice Biennale.

The weird reflections of diabolical others, the off-kilter depiction of Beckmann’s eyes and hands, its lack of sentiment, its lassitude, its futile posturing in view of a demonic neighbor, its astringent, grayed-down palette, the chalky white and yellow skin colors, the warmth of the ground, and its strange treatment of the body, all this in Beckmann’s besotted Self-Portrait with Champagne Glass beguiled me. I transcribed this tipsy self-portrait of the world’s weariness. A perfect summation of 1919. A visually satisfying figurative painting.

My Beckmann’s Self-Portrait, 2007, oil on canvas,

approx. 20" × 18"

More than its connection to history and its era, Beckmann’s self-portrait was my artist’s version of the French medieval history that had first brought me to the study of history—the freedom to be drawn to the work just because it intrigued me. It is a weird painting whose secrets of weirdness I probed through transcription.