Frank and Dona Irvin at Their Seventieth Anniversary, Oakland, 2007, digital photograph

La di da di da di da, as carefree as I could be.

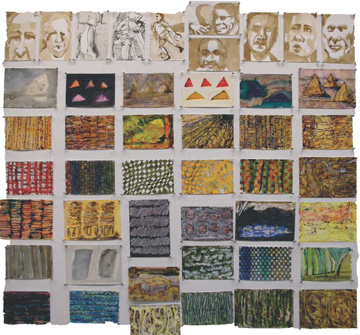

I drew and drew my one hundred drawings for Hanneline, la di da di da di da.

As the summer was ending, there came a crisis. Another crisis in Oakland. My parents. My father, weeping, could only hand my mother the phone. I had to come to Oakland, now. That call—tears, desperation—not the first such summons to Oakland, nor the last, not by far, but the first in a last sequence.

My parents were calling from their cottage at Salem Lutheran Home, where they lived independently in their own little house. Every resident wore a panic button. They had not pressed their panic button. They had not called the nurses’ station for help. Despite Dona’s night of excruciating leg pain, they even waited before calling me for help, Frank massaging Dona’s legs to assuage her pain, inadvertently increasing the risk of moving a blood clot. She howled in pain; he gave up. Desperation pushed their call to me. Diehard sense of independence forestalled further outreach. Independence, my mother’s watchword.

Dona went to Kaiser Permanente hospital’s emergency, perhaps for surgery, perhaps to lose a leg, and, unsaid, the ultimate worst possible fate. My poor father, emotionally collapsed from depression, wept over this latest possible loss, but he now wept over everything. My father had not always been depressed and wrecked, quite to the contrary. Over the course of many decades he was loved for his looks, cherished for his generosity of spirit, and profoundly appreciated for his willingness to help others, whether through sympathetic listening—he was the world’s most empathetic listener—transportation, or even money in times of need. His were not just ingrained good manners, though he was known for gentlemanliness. When you talked to him, he listened, he responded to what you had actually said. Caring for other people and good listening made my father everyone’s hero, even in those times when that good person hid from view. He had been a depressed wreck for years, unable to do more than wait for me to come from New Jersey to fix things. We knew this drill all too well by then, for my parents had already been deteriorating. By the time they reached their late eighties, Glenn and I could see them as frail.

When I say “see them as frail,” I have a particular morning in Oakland clearly in the eye of my mind. Before moving to Salem, my parents lived in the hills above the Oakland zoo. A mile or so farther up lay a hilly East Bay Regional park where my father walked his dog every day before depression nailed him to his bed. Usually he walked alone with his dog, Dona only rarely accompanying him, for the hills he walked were too strenuous for her heart after years of smoking. One sunny morning when Glenn and I were visiting, before things started totally collapsing, the four of us walked a flat path in the park.

Most of the path crossed open grassy rolling hills where you could see the San Francisco Bay, San Francisco, downtown Oakland and Berkeley, over to Richmond and Marin County. No question about it—the Bay Area is the most beautiful place in the world. Whenever I’m there, I ask myself why on earth I still live in New Jersey.

That morning Frank and Dona walked a flat path with trees on either side. Glenn and I followed, watching them lean on each other, essential supports for seventy years. They were so tenderly interdependent, so deeply and so lovingly connected! We teared up over the sight of them in the arid California bower, so tottering, so frail, like the figures on a wedding cake, but collapsing. We could see they lacked the strength to live on their own.

It took Glenn and me two years to get them to agree with each other on moving into continuing care in Salem Lutheran Home, a process that entailed an exasperating churn of home health aides. Once Dona and Frank were settled in their new home in Salem’s Redwood Cottage, I had started art school thinking my parents were stabilized. (Just as mistakenly, I had thought my book was finished.) But now Frank and Dona were failing. They had been so glorious a couple for more than seventy years, a sane, open, liberal, handsome pair, as welcoming to gays and lesbians as to straights. Everybody wanted them for parents.

My parents the paragons. People adopted them as replacements for their own lesser families. My poor parents, for so long a gorgeous, inspiring couple of progressive, intelligent beauties! No longer.

The desperate call from my father at the end of the summer of my one hundred drawings was pathetic entreaty and parental command. This was not Dona’s first hospitalization or the first urgent trip to scare me to death. Intense leg pain had sent her to the hospital a year earlier, and low blood pressure had kept her in intensive care. Angioplasty was the remedy then. Now, a year later, my mother was again in intensive care, and my father was once again weeping, commanding, and beseeching me to drop everything and fly to their rescue, his condition as alarming as hers.

We need you now.

I put my paper and ink aside, washed my pen, and flew to Oakland.

Thank heaven I had already finished my book manuscript and sent it off to the publisher. The damned thing had taken so long that I was calling it My Fucking Book, MFB for short. Of course, it would come back for more tinkering, but it had passed the monumental final manuscript stage. I had made a drawing of the final manuscript sitting on my worktable in the Adirondack screened porch, a block of pages so tall one of my Mason Gross mentors called the pile a sculpture.

MFB, 2008, ink and oil stick on paper, 6" × 9"

For a crazy moment I imagined the trip to California as an art opportunity. Maybe I could meet Mary Lovelace O’Neal, a terrific abstract artist at the University of California–Berkeley whose work made me think of my idol, Robert Colescott. I had first discovered O’Neal while researching the art that illustrates my Creating Black Americans, drawn initially by her brilliantly colored, composed, and titled Racism Is Like Rain, Either It Is Raining or It Is Gathering Somewhere, a 1993 lithograph featured by the California African American Museum in a Los Angeles show inspired by the Rodney King disturbances. O’Neal is my age, and she makes the kind of work I find myself attracted to: gestural, abstract, brilliantly colored, full of movement and action, and hinting at figuration. Though O’Neal’s work is in public collections, and she holds her share of international honors, she is a black woman painter of the modernist generation who could not pierce the veil of mainstream art history. I hoped to meet her, or even just to tell her she meant a lot to me as an artist. In Oakland I bought some art supplies in case I might continue my one hundred drawings.

Envisioning art in Oakland could not obscure the dismal facts, and the facts were truly dismal. My parents were disintegrating, Frank from depression, Dona from congestive heart failure and from the anxiety of Frank’s anger whenever she did anything he wasn’t ready to do—which was anything whatever, whenever. His anger consigned her to his paralysis, impossibly hard on Dona, ordinarily the personification of energy. I knew she had collapsed from exhaustion. We had already seen the signs: her increasing confusion, loss of concentration, inability to use her computer to check her email. Worst of all for her, she was stammering again after a quarter century of fluency.

My father said he was feeling “thrown away.” How could that be? His misery was so misconstrued, I thought, for his situation was excellent. After decades of walking his dogs in the Oakland hills, his physical health could hardly have been better. He was married, financially comfortable, loved, and well cared for. All for naught. He felt absolutely rotten and spread his naught around. This made no objective sense, kind of like unhappy rich people, weeping in the midst of splendor. But what use was objectivity? My parents were driving me crazy, for I knew they were safe, 100 percent better off than so many their age. They had the finest of health care at Kaiser Permanente and an abundance of friends, some for half a century or more. Depression and congestive heart failure, yes, but no Alzheimer’s or dementia, no poverty, no diabetes, no cancer or broken hips. No matter. My father peered into his future and saw only hopelessness. He shook and wept and gasped for breath. He said he no longer wanted to live. Dona feared he was dying. Something had to be done, but his psychiatrist had tried every medication available.

MY POOR LITTLE mother! In the intensive care unit she became delusional, imagining herself on an airplane about to take off, leaving Frank behind. She worried and fretted, trying to get us to delay departure, making us promise to hurry Frank up. He always needed hurrying up, even when he was perfectly well. In the ICU Dona was still confused, but adorably childlike in her half-confused, half-cognizant state. In the morning she was easily distracted. As I fed her some breakfast to make sure she ate, she chased other thoughts. This was the first time I had fed one of my parents. But it was not to be the last. Art school or no, I was in charge now.

Dona had been our family’s organizer, our super-duper originator, arranger, instigator, architect, executrix, and producer. Our affairs had run smoothly for so long that I had never felt the need to step into the middle of my parents’ (outwardly) sunny existence. I loved them; they loved me; everybody loved them. They had whole new families of friends. I always kept in touch over the years, but not continually, in the way of my fellow Mason Gross undergraduates, constantly chatting with their parents by cell phone about what I overheard as trivia, like what to wear on an ordinary day. Even in my parents’ mid-eighties, they were still strong, Dona organizing their next steps in lists of their finances, including account numbers and institutional contact information. She even sent me a document labeled “Body Disposal” with all the information I would need when they died, or, as they preferred to term it, once they “made their transition.” Frank was in no shape to appreciate Dona’s organization, but I certainly did. Glenn sometimes poked fun at Dona’s documentary excesses—she tallied up the attendance at their fabulous seventieth anniversary party before pronouncing herself satisfied.

AS THOUGH THEIR lives drew from a single reservoir, Frank rallied as Dona declined. His depression had dragged her down until she collapsed, then his depression relented. During her hospitalization, he visited her with me and sat with her in her hospital room. I read to them from Barack Obama’s first memoir that we pronounced excellent, candid, and sensitively, elegantly written. Frank and I sat transfixed in Dona’s hospital room as Obama accepted the Democratic nomination for president, a wondrous thing neither of us had imagined possible within our lifetimes. At this same awesome moment, Dona lay elsewhere mentally, agitated, confused, and hallucinating. She was questioning what we couldn’t see on the ceiling of her hospital room and picking at her bedclothes. She drifted off to sleep during Obama’s Great Historic Speech, never aware it had taken place.

WHILE WE IRVINS were absorbed in our family drama, the Democrats were making history every night. Michelle Obama was beautiful and touching. The Clintons did right. Joe Biden called on his people—the firefighters and police officers (but not the hospital and childcare workers). Obama was tough and beautifully ethical, balancing talk of unity, purpose, and respect with policy and nice criticisms of John McCain’s $5 million/year = middle class, and the Republicans’ so-called ownership society, translating it as you’re on your own. My father and I savored every momentous phrase, every transcendent image.

I felt proud of Americans’ working through hotly contested matters. The Democratic National Committee wrestled with contending delegations from Florida and Michigan and reached compromises without drawing guns. Some time ago I would have taken quite for granted the nonviolent resolution of political differences. No longer. In these days of electoral bloodletting, of slaughter in cinemas and grade schools, in churches and casinos, when contested elections produce ethnic cleansing and everybody carries a gun, I felt, still feel, Americans have done something fine.

I remembered a conversation with a Haitian taxi driver taking me from Princeton Junction to Princeton during the drawn-out settlement of the 2000 presidential election. He kept All Things Considered on his radio because, he said, he marveled at the peaceful settlement of political controversy.

FOCUSING MY FATHER beyond his misery, the 2008 presidential campaign kept him alive. His attention had not always been so closely circumscribed, for years ago, before passing eighty-five, he had subscribed to the daily New York Times, the actual paper, I mean. By his late eighties he could no longer take pleasure in the paper as a whole, but in 2008 his interest in current events revived. He followed Frank Rich, Bob Herbert, and Gail Collins, relishing every report of John McCain’s weaknesses, especially after Sarah Palin dirtied up the campaign. In Oakland I read to my father from the Times online every day.

Glenn and I helped Dona and Frank fill out their absentee ballots, allowing them the historic gratification of voting for Barack Obama for president of the United States of America. A milestone of milestones, an occurrence that changed American history. For a while, anyway, very much for the good. I credit George W. Bush for making my parents’ vote possible, for opening Obama’s way. First, Bush appointed two black people to the previously unattainable—even unimaginable—position of secretary of state, one a black woman—a black woman who was not an immigrant or child of immigrants, not even a woman with skin light enough to comfort American eyes. Okay, okay, Bush and his people trashed Colin Powell, and Condoleezza Rice was as feckless and right-wing as the rest of the Bush people. But she and Powell remained black. Had a Democrat tried to appoint black people to so prominent a position, the Republican uproar would still be resounding. I felt any such appointees (and they surely would have been as able as Rice or Powell) would have been Lani Guinierized, shredded by mean-spirited lies. But good-ole-boy Republican Bush did the impossible. With the actual fact of black secretaries of state, the domain of the possible widened. If Powell and Rice could be secretaries of state, maybe a black man—a man, mind you—could be president.

By my lights, Bush’s second gift to Obama was a disastrous presidency, early bringing thousands into the streets against the war. Then the Great Recession scared everybody to death in 2008. By that point, things had descended to such a nadir that Americans opened up to extreme measures. Obama was so different from Bush that he could appear as a remedy.

The great fear, of course, was that some American would shoot him, in another tradition aimed at charismatic political figures, especially those who are black. Michelle Obama confronted that threat directly, saying that in the United States a black man could get shot just going to the grocery store. Subsequent events have shown this as literally all too true.

MY MOTHER IN the hospital, I got to live my own life in Oakland for a couple of hours. I searched for contact information for Mary Lovelace O’Neal, that terrific abstract artist at Cal–Berkeley, who was pretty damned well hidden. I finally unearthed an email address that she never used. I visited my friend Anna’s studio and gallery in San Leandro, where Anna and I talked about materials and curating, about colors and taste, about the art market in general, about the market for work by black artists, and about making work that fits the pocketbook of black buyers. Anna lamented that most of her buyers were white, because she wanted also to reach black buyers. We pondered our situation as American artists, in which the race of our buyers would seem to matter. Anna was happy to have buyers, and that put her ahead of me.

DONA LEFT THE hospital, but not to return to Redwood cottage. She moved to room 107A in Salem’s skilled nursing department, a kind of mini-hospital. One day a group of my parents’ close friends from the First Church of Religious Science made a prayer circle around we three Irvins, Glenn having departed to teach in New Jersey. The friends prayed and sang over us in a most beautiful and moving fashion that sent tears down my face. They hugged me and let me lean on them. That felt lifesaving physically and emotionally.

A day or so later, two other Religious Science ministers came to talk with us, giving Frank and Dona a Religious Science “treatment” that raised their spirits, Frank’s especially. I’m not religious, but the treatment felt good to me, too, as an uncanny infusion of encouragement, a physical embrace. I thought I understood the fact of my mother’s impending death, but I had not. I had no idea of the feelings and fears and complications, the pit opening up before me, the loss of the key to my identity. I also had no grasp of the enormous support I enjoyed from my parents’ strong network of friends. Thanks to them, I was not going into this alone.

One morning Frank asked me what would happen to Dona. I said the short answer was I didn’t know. I really couldn’t know what I knew, even though I knew it in a place I could not reach. I admitted the long-term prognosis wasn’t good. He shuddered and wept.

One mental image I kept was my frail, nearly ninety-year-old father walking from Salem Lutheran Home, down and back up the hill on 23rd Avenue to the convenience store for ice cream for Mom. He was so vulnerable! He could not satisfy her demands in the angry phase of her mortal illness, a rage that reduced him to tears. He wanted so much to please her. This new ability of hers to be angry with him fascinated me and demoralized my father. He cried,

We’ve been together for seventy-one years. We’re like one unit.

I agreed with him. But when he said he couldn’t live without her, I asked him not to go there, to take it one day at a time.

I hated to think it, but I hoped that an end to this long marriage might lift my father out of his depression. Already Dona’s breakdown had gotten him out of bed more than in years. Maybe both my parents were suffering from too much togetherness for too long a time.

WITH DONA RESETTLED in Salem’s skilled nursing, I returned to Mason Gross. Back in New Jersey, I grappled with my mother’s impending death, and not for the first time. It had already come up on account of her mental instability and weakness. Her hold on reality wasn’t firm, but her spirits were pretty good, for she didn’t understand the gravity of her situation. But whenever I told others she suffered from congestive heart failure, their faces fell. As I told Glenn these things, he began looking at his calendar for when we could return to Oakland. Glenn was teaching every Monday, so any visit on his part would have to accommodate that schedule—somehow. But me, I felt as though I should just go to Oakland for the duration. Fuck it. Just let my semester go.

Let it all go. In the end, I didn’t let the semester go, even though there were, what, six? seven? trips to Oakland that academic year.

I managed to keep up with my Mason Gross classes, but my work spoke bleakness. After an evening in the basement drawing and painting, I went to bed feeling oppressed. I couldn’t shake Teacher Lauren’s adjective for my portfolio of new drawings: “dreary.” She came down hard on those pieces, offering a little criticism doubtless meant as constructive, but I couldn’t hear constructiveness. “Dreary” stuck most tenaciously, because I was so tired that dreary described my being as a whole.

LEFT: Pan in Brooklyn, 2008, ink on paper, 22 ½" × 30"

RIGHT: Ruth Disappears, 2008, ink and white conté crayon, 18" × 24"

One of my most helpful mentors, Artist Friend Denyse Thomasos, described my work in terms I never could have come up with on my own. She noted my acid tones, my grayed, low-contrast palette, the open spaces, all conveying a sense of isolation and sadness. She said my paintings translated my anguish. After crit, I collapsed on the floor of my studio, exhausted, but unable to nap, my hysterical knee throbbing despite multiple ibuprofens. I was emptied out and queasy, with a canker sore in my mouth. I was so tired, so very tired. And my studies seemed so futile.

My father wailed on the phone that he was close to his breaking point, crying again—he was always crying—back in his all-too-welcoming despair. Depression is definitely contagious, and he spewed depression all over me long-distance. My poor mother must also have caught it over the years and was still now catching it in his hours at her bedside.

One day in New Jersey in my car on the way to New Brunswick, I waited for the light to change at Bloomfield Avenue and JFK Drive to take the Garden State Parkway. Exit 148. The wind blew dead leaves across the intersection, a wave of desolation on a cold, cloudy day. Through the car window I couldn’t hear the leaves’ clatter. I knew the soundless sound, a dry rasping, “it’s over.” The worst of my sorrow subsided as I drove up the ramp and onto the Parkway. The deaf graphite rattle of leaves in the wind.

IT WAS THE first day of final crits in Hanneline’s class. Only two other students and I were there on time at 8:15. Matt had spent the night in the classroom, another last-minute, overnight wonder. I had seen this phenomenon before in other classes with other students, and I always admired the originality and scale of pieces made overnight. A student who seemed silent and mediocre in class would make a masterpiece, a twenty-four-hour marvel of invention I could never envision. They could do this, the youth, just now producing a huge, handsome collaged drawing, a tour de force that did not relate to any of our assignments. Such unfettered freedom left me slack-jawed in admiration—for the work and for the freedom to disregard what had been asked of us.

The freedom of disregard.

I put my final project drawings up first to claim an entire wall. By the end of the abbreviated class, only six of us had put up work. My friend Madeleine came to give me moral support and loved my final project, my massive, three days’ worth of drawing produced in an uncanny, desperate effort following California. She initially assumed it too good to be mine. But in a nice way.

WHEN GANGRENE SET into my mother’s leg, I prepared to leave New Jersey at any moment for her death. In BFA thesis class I showed my classmates the four paintings I wanted in the BFA show. They promised to hang my pieces for me, a favor that was welcomed and, finally, needed. Out in the world the news was scary. More firings, unemployment up to 7.1 percent. Republicans still screaming for tax cuts. Obama still trying to accommodate them, even though they wanted to trash his plan to save the American economy. I was hoping his expectation for bipartisanship would work out, though the Republicans were being awfully naughty.

My father was spending nights in my mother’s room in skilled nursing under a blanket the nurses gave him for his bedside vigil. On the phone he told me, weeping, that Dona had said—to the room, not particularly to him:

I don’t want to die.

This broke his heart again, and it echoed in my ears all night and into the morning. The remarkable thing in her statement and in his repeating it to me was the forthright phrase “to die” instead of their New Age euphemism, “to make one’s transition.” They were both preparing for the inevitable, though I still didn’t have an idea of when, exactly, it would be. Perhaps Frank was expecting “the end” sooner than it would actually occur, perhaps out of grief fatigue.

I was in my lithography class when a phone call from Dona’s hospice nurse interrupted the counter-etch of my litho plate. Come immediately, she won’t last out the week. That call from Oakland plucked me out of a morass. I had been so sluggish, so emptied out and exhausted, more debilitated than my usual tired. I was living a muddle, struggling through a swamp of slimy, clotted vegetation ensnaring my legs and feet in a bottom I could not see. My actions lacked all meaning. That was how I felt, even though I had not wasted my time. There was a disjunction between my feelings—narcose, lethargic—and my actions—effective and organized. Through the fall’s anxious weeks, I had been working on copyedited MFB and took chapters twenty-five through twenty-seven to Oakland with me.

Frank’s response intrigued me, for he was unusually composed in those very last days of his vigil by Dona’s hospital bed. That vigil carried him to another plane, where he slept better and nearly relinquished self-pity. Would his depression lift with Dona’s passing? Glenn saw Frank’s depression as a response to her failing health. I rather saw it the other way, that she broke down under the strain of trying to keep him going. Maybe we’re both right, as my parents were so intimately connected.

AT SALEM, I returned to what had become my second home, the little no-color, one-room cottage 2C: single bed, bureau with a boxy old-time TV on top, night table with lamp, bathroom, and closet, everything brown and gray and sad worn-out white. The whole cottage was smaller than our bedroom in Newark. The radiator clanked infernally all night. Salem’s feral cats yowled outside unceasingly.

Over in skilled nursing, my mother was comatose, eyes 90 percent closed, mouth open, head back, oxygen tube around her nose and neck, its pump both generator and iron lung and sounding like it. A noisy thing, never letting me forget its life-giving function. The time would come, and soon, when it would no longer suffice.

My father was keeping his watch, another night in the chair by Mom’s bed. He held her hand, monitoring the relative strength and weakness of her pulse. I watched the faint rise and fall in her throat of her breathing. He stayed in Dona’s room, saying he couldn’t sleep at home for worrying about her. I believed him.

Dona had many visitors in her last two days, some praying and singing her over. A Religious Science friend sang sweet Hebrew songs to comfort her dying. Even though Dona couldn’t register any reaction, we knew she knew we were there. I hoped so; Frank certainly hoped so, wanting so deeply to be with her when she “made her journey.”

The process of my mother’s dying lasted more than two days, her face going slack, not just mouth open, but tongue falling to the side, jaw also slumped to the side, and eyes sunken and unfocused. I hadn’t thought before of all the muscular effort required to hold the face composed. Except for the obvious exertion required to express emotion, I took muscle tone for granted. But I see now that even a lack of emotion makes muscles work. Dying releases everything, like a stream feeling its way down a landscape, seeking its lowest level.

My mother died at three in the afternoon on a Thursday. My father and I were both there, one on either side, each holding a hand, when she died. Emptiness. Frank summoned the strength to go to Mosswood Chapel mortuary with me to sign her death certificate. Where did he find the power to face this testament of ending? I didn’t ask this about myself, accustomed as I was by then to taking charge of my parents’ lives and fates. I think now that Dona passed organization on to me in a transfer she had begun years before as part of my inheritance.

Before Thursday ended, the mortician took away what was left of my mother in a small black plastic bag. Though I had been with her as she died and sat with her for a time while she was very dead, the smallness of that package shocked me. A plastic bag contained my entire mother, except for the twenty-one grams of her soul. That small plastic package sealed her deadness. A living person, asleep, might be stretched out on a bed in skilled nursing, but a person still alive could never fit into so small a black plastic bag. It seemed a final insult, the diminution of my beloved mother into a parcel to be carried by hand.

I WAS DOUBTING my artist’s bona fides before my mother as a visual spectacle. If I were a real artist, I accused myself, I would have drawn or photographed her dying. I had that thought before she died, struggling to make myself see her as a motif and to draw her. But I could not draw my dying mother, even to insert her image into my one hundred drawings. I could not take my sketchbook into her room, a gesture that I felt would distance her from me. I tried. I failed. LaToya Ruby Frazier made a poignant series of photographs of her family’s physical decline. Annie Leibovitz photographed the fatal illness of her partner Susan Sontag. Roz Chast made an entire, hilarious book about her parents’ old age, ending with sober drawings of her mother on her deathbed. I could not do that. Feeling numb, weeping now and then, I loaded my failure as an artist onto my daughter grief.

HOW TIRED COULD a person get? I was plumbing the depths of exhaustion swamp as never before. Lord knows, I’ve been tired in this life of mine. If my prior experience with exhaustion weren’t so extensive, so, well, exhaustive, I’d say I’d never been so tired in my life. So I just collapsed in my infernal 2C cubbyhole, with the diabolical radiator clanking all day and night and the goddam cats yowling.

It took weeks to wind up my mother’s death and arrange her triumphant “Celebration of Life” at the First Church of Religious Science in Oakland. Even cremated, my mother, from her perch in wherever it is good people go after death, would have been counting up the four hundred and more who came out for her. My father managed Dona’s celebration with his erstwhile charm and grace. Once the public appearance ended, he fell back into depression. He left me to deal with everything, every single fucking thing. And then, to all his many friends, he accused me of abandoning him. I was furious, totally furious at his disregard. Finally back in New Jersey, I was a wreck.

I RETURNED TO classes at Mason Gross with my hysterical leg—not just knee, the whole fucking leg, groin, thigh front and back, knee all around, calf front and sides and back, ankle all around, all throbbing like hell. Muscle-relaxing pills didn’t help. Breathing into the pain didn’t help. Three Excedrin didn’t help.

One day in lithography class I felt faint.

Sit down! Sit down!

My eyes would not focus.

Sit down! Sit down!

Other students’ voices went muffled.

Sit down! Sit down!

I had to sit down, but sitting was too hard.

Lie down! Lie down!

I lay down.

I lay down on the floor behind the press, didn’t care who saw me.

One Hundred* Drawings for Hanneline, 2008, mixed media, dimensions variable

No one saw me. They were too far away at the other end of the room and too absorbed in their own work. I just blotted into the floor behind the press.

Strength and focus returned in a few moments, at least I thought it was a few moments. I stumbled down the hall to the water fountain and drank. My poor old body, my poor old woman’s body, just could not manage it all any longer.

My doctor named this syncope, passing out. At least it wasn’t a stroke. I managed to complete my Rutgers semester, to show some of the sixty-seven, not one hundred, drawings in One Hundred Drawings for Hanneline, and graduate. Whew.