You know now that Teacher Henry proclaimed his truth that

I may show my work.

I may have a gallery.

I may sell my work.

I may have collectors.

But I would never be an artist.

And you know my retort,

Henry, that’s bullshit.

Ontology or epistemology? The twentieth-century German Bauhaus notion that art cannot be taught held on until right down to Henry at RISD. Within that mystic ideology of the ontological An Artist, education cannot really help make art. As someone who had been in academia her entire life, I clung to my belief in education, whether my teachers did or not. Thank heaven Artist Friend Denyse reassured me that the language of visual art could be learned.

I figured out that “You’ll never be an artist!” was meant mean-spiritedly, as a way to take me down a peg—knock me off my high horse, put me back in my place, something like what that drunken Harvard lawyer at dinner in the Berkshires tried to do. That realization came only later, as I felt my own way into making my own art. Friends suspect I may have threatened my teachers, who may have been struggling against misgivings over their own status as An Artist artists. I don’t know. Be that as it may, Henry’s comment both enraged me, as I recognized it as criminally bad teaching, and humiliated me, by feeding into my colossal graduate-student insecurity. His comment doubtless said more about him than about me, which was of absolutely no help whatever. I was only thinking about me.

I WASN’T FEELING appreciated for my real strengths—intellectual sophistication and visual ambition. To the contrary, my strengths felt like impediments. Better to make abject images of toasters and trash bags or paintings in which accidents conveyed enigmatic meaning. Recognizable meaning seemed embarrassing to the painters around me, and, I suppose, if I had been a more acceptable painter, meaning would have embarrassed me, too. But it didn’t embarrass me, and I persisted along my own singular path. That path brought recognition in the world I had come from, in the form of commissions for book and journal covers. Signs reproduced details from two panels of my Harriet Tubman series. Fierce Departures and Chronicles, by the poet Dionne Brand, used abstract drawings I had made by hand and then digitally recomposed in colors that were bright and subdued. For the cover of My Dear Friend Thadious Davis’s book Southscapes, the designer used two searingly colored drawings I had made from a black-and-white 1930s southern photograph. My artwork was circulating outside my art school.

It was a wonder I didn’t lose my mind, or maybe I did. On some level I knew myself to be a super-duper intellectual, author of a blockbuster book, an Argonaut venturing where few dared to tread, et cetera, et cetera, Superwoman but not in such tight skimpy clothes. I was a star and a dud, simultaneously.

TOP RIGHT: Cover, Fierce Departures, by Dionne Brand, 2009

BOTTOM LEFT: Cover, Chronicles: Early Works, 2011

BOTTOM RIGHT: Cover, Southscapes: Geographies of Race, Region, and Literature, 2011

SO WHO THE hell is An Artist? Joseph Beuys said everyone is an artist, which is manifestly not true, either potentially or in terms of how you spend your time. It does seem that anything can be art, not only Marcel Duchamp’s urinal and bicycle wheel, but also the contents of your dorm room or a list in a tent of everyone you’ve ever slept with. Arthur Danto supplied an answer that still serves: art is what is shown in the context of art, that is, what’s put on a pedestal in galleries (is my living room a gallery?) and exhibited in a museum (what’s a museum?). A value judgment suspended between market value and aesthetic imagination. Add what the art world calls the critical consensus, what critics agree is the right stuff, along with three queries: Who counts as a critic? Where does the criticism appear? When do you take your snapshot to capture consensus?

I wish I could say this reasoning comforted me on a daily basis—it did not. I didn’t have to contend with the armies of negativity every day. But those armies bivouacked right nearby, ready at any time to defeat me. Just holding them in their barracks exhausted me.

I didn’t know whether my fellow painters were struggling against armies of their own, even whether they were hearing criticism that made them question if they should or could stick it out. One rule about being An Artist is never to voice doubts, about yourself or about your work. “They” will use your doubts against you, especially if you are a black artist. That rule seemed to hold even among white artists, who even before so much as a hello were always touting where they had just gotten off the plane from and the places their work was being shown.

My fellows could have been doubled over in psychic pain in their studios or enjoying their Narragansett beers in serene self-assurance, leaving me as the only one hanging on the precipice of quitting. Intellectually I knew I was not the only one in the world harboring doubts. Later on when I would tell that story, someone would reply with their version of discouragement, their or a friend’s leaving art school decades ago in the bad old days or only yesterday, often a woman, but sometimes a man, usually white, because non-white students in art school are rare. At the time I felt alone in my miserable alienation. Conflicting thoughts, confounding emotions as my everyday situation.

I held yet another set of thoughts at the exact same time. Sure, I might not be good enough, but many artists, An Artist artists, aren’t good enough in other people’s eyes. The curator of MoMA’s PS1 told Dana Schutz, one of the leading painters of our time, “You must be the worst painter I’ve ever met.” If you didn’t know Amy Sillman and Nicole Eisenman were huge successes, you might question whether their draftsmanship was “good enough.” I had overheard students belittle the painting skills of Kehinde Wiley, President Obama’s official portraitist. And I knew my own surprise at Jackie Gendel’s artist’s talk, where she showed the progression of her art as she made figurative paintings. A lot of them were badly drawn and badly painted. But she had people on her side as she kept at it. Jackie Gendel is An Artist with gallery representation. Another cool visiting artist, Trenton Doyle Hancock, sent RISD students into raptures with work on a mythological scale, pulp culture, cartoons, imaginary fantasy worlds, text, personal and biblical narrative, all rooted in the art history of Hieronymus Bosch, George Grosz, Philip Guston, and R. Crumb and carried off with faux naive craftsmanship. His work exceeds judgments of “good” or “bad.” I saw his work in his gallery in Chelsea. Definitely An Artist.

GALLERY REPRESENTATION, I quickly learned, is the main criterion for who counts as An Artist. I once filled out a questionnaire for artists that divided us into two categories: those with gallery representation and those without—the better class and the lumpen. Even if you thought Gendel’s paintings weren’t very good or Hancock’s were childlike, you had to admit they were An Artist artists because of gallery representation. How do you get a gallery? You make work that counts as interesting in the eyes of An Artist with a gallery. Who are artists with galleries? Your teachers, your peers, your friends. They persuade the gallery director to visit your studio and concur that your work is interesting. There are so many galleries and so many ways of making art and so many good artists, even, and a whole lot of even bad artists have gallery representation. How do you tell what art is “interesting”? It looks like art. What is art? Art is what’s in galleries. Now you know.

I learned another way to recognize An Artist artists. We graduate students would visit their studios to admire their process or at least recognize theirs as ways An Artist artists make art. There was the artist who poured acrylic paint on plastic sheets, let it dry, and glued it to canvas. There was the artist who projected pages from old IKEA catalogs and painted them mimetically in large format. There was the artist who put her paper on the floor and walked on it to make her marks. There was the professionally trained British artist who purposefully painted like a child. Clearly there were hundreds, thousands of ways to make art and to be An Artist.

RISD Teacher Kevin and Mason Gross student Keith used gallery representation as taglines of artists’ identity, as though their galleries were their last names. (Some annoying writers do this to size up other writers according to the prestige of their publishers.) You rank galleries along a scale of coolness, so that attaching Pierogi to an artist’s name would definitely sound good. Not just any gallery—not just any Chelsea gallery on the ground floor—could make an artist An Artist or a cool An Artist.

Gallery representation, as one sign you are An Artist, connects to two other criteria: selling your work and having collectors, two different things. I sold a little of my work even before going to art school, to friends and occasionally to colleagues. I know painters in Newark who haven’t gone to art school who have sold way more art than I have or ever will. Plein air painters, cowboy painters, painters of pop star portraits and horses in sunsets can all sell circles around me. After all, who was the bestselling contemporary painter? Thomas Kinkade (“Painter of LightTM”), with his nostalgic, kitschy scenes of Victorian mansions all lit up in the kind of deep snow that global warming has extinguished. Selling like crazy, but hardly An Artist artist.

Selling their work is a criterion very few artists can fulfill, even An Artist artists with gallery representation, solo shows, and work in public collections. Some years ago the painter Susan Crile won her Internal Revenue Service appeal that was all about sales and professional status. Because she listed very few sales, the IRS sued her for back taxes, reclassifying her art as a hobby rather than a business. This counts financially, because you can’t deduct hobby expenses; business expenses are tax deductible. Crile hadn’t sold enough art to make a steady profit, even though her work was in museums. She won her case in tax court, vindication for us all, for very few artists, even An Artist artists, make enough money to live on through sales of their work. Those who do are—this won’t surprise you—disproportionately white and overwhelmingly male.

To be recognized as a serious artist, An Artist artist today, you need an art degree, an MFA, not just a BFA, though the essential graduate degree won’t pay your bills. Even artists well enough credentialed to teach in higher education aren’t making much money. Nowadays most artists teaching in colleges and art schools are adjuncts who either scrape by financially or teach in several institutions at the same time. I should say and/or teach in several institutions. Art and sustenance often conflict, for earning a living will prove fatal to your art if you have to spend too much time on the road chasing from gig to gig to paint. I didn’t have to take a day job in order to live, thanks to my Rutgers professor husband. My financial well-being may have counted against the possibility of my being An Artist. To explain, I need to return you to my studio for another studio visit from Teacher Irma.

She was razzing me about wrong painting, and I, pathetic as usual, was trying to propitiate her. I riffled through the computer in my studio, desperately hunting for a work I hoped would meet her approval. She glowered. I searched. I couldn’t find the image I was searching for. I apologized.

It must be in my laptop in my apartment, I stammered.

You own two laptops? Irma shrieked.

Yes, I owned more than one computer, I confessed. But one was just a dinky little white plastic laptop! (All right, it was a MacBook.) Another demerit on my record, another obstacle between me and An Artist artists. And I hadn’t even begun to approach the collector criterion.

Collectors. When people in The Art World say “collector,” they mean rich people. Really rich people who own more art than they can put on their walls at one time, even though they have lots of walls in multiple houses. They fly private jets from one international art fair to another, rotating between glitzy parties in exotic rooms. These big-name collectors, like François Pinault, Alice Walton, Walter Evans, the Rubells, David Driskell, the Broads, Dakis Joannou, Nancy Lane, the Chenaults, and Agnes Gund, are known for owning the work of superstar artists like Koons, Warhol, and Basquiat, mostly male New York artists. Hardly any of the big collectors are black, as are few of the artists they collect. This is changing to a certain degree as society desegregates, but there’s still a very long way to go.

Big-name collectors serve on the boards of museums and contribute dollars, euros, and, increasingly, United Arab Emirates dirham and Chinese renminbi in the six and seven figures. They donate art from their personal collections to their pet museums, public and private, that turn the artists from their collections into “museum artists,” attractive to other collectors. At auction, museum artists’ work can sell for millions; in galleries, for hundreds of thousands and more. Collectors sometimes stand in line to buy work that hot artists haven’t even made yet. Those hot artists are clearly museum artists, An Artist artists. I could see that museums, like galleries, were ranked according to wealth, status, and coolness. Obviously New York museums—MoMA and the Met and the Whitney and PS1 and the New Museum—sit at the top of the heap. Through the sponsorship of wealthy philanthropists, the Studio Museum in Harlem comes in close behind, having moved up in a generation from scrappy alternative space to premier destination for collectors and for hot young artists trained at Yale.

Henry was right that I would never be that kind of An Artist artist, though, as he conceded, I may sell my work; I may be represented by a gallery; I may have collectors. In fact, I already have collectors in New Jersey. But do collectors in New Jersey count? Oh my, I had so many deficits: no gallery, few sales, and New Jersey.

YOU KNOW, BACK in graduate school, I should have ignored my deficits. Even better, I should have flaunted them, making art according to my own bad-artist’s hand, and lots of it, like a woman in the undergraduate painting class I had to take in the winter session of my first year. Sulking over my punishment, I envied her freedom over in the large corner she had commandeered and turned into her own personal studio.

Mary wasn’t a regular RISD student. She was on the staff, taking a painting class just for the hell of it. No one was telling her to work on her skills. She fenced off her corner with piles of the work she made with a cadmium-red-hot-furious, total disregard. She made tons of work, most of it junk. But some of it grabbed you and would not let loose of your eyes. Some of it exploded with all the energy she threw—and I do mean threw—into her paintings.

The rest of us in the class, mostly undergraduates, were dutifully painting studio set-ups with models and a collection of miscellaneous objects—tires, fishnet, pots, chairs, and fabrics—things famously hard to depict. I hated every last damned painting I made there, so stinking were they of art-school set-ups. There I was, laboring like an undergraduate over verisimilitude, striving to capture the set-up, when I should have been, like Mary, painting what my hand was seeing. I was trying to paint as I thought I was supposed to in order to improve my skills. I hated hated hated every fucking moment in the studio in that class. Mary loved it with matching fervor.

Over in her corner, she painted, tore up her paintings, pasted them together in every which way, assignments be damned. To hell with the assignments! To hell with the blasted set-ups! Meanwhile, boring old me painted my stupid paintings by the rules. I’d never be an artist, never be An Artist. What would I be?

A T O T A L F A I L U R E

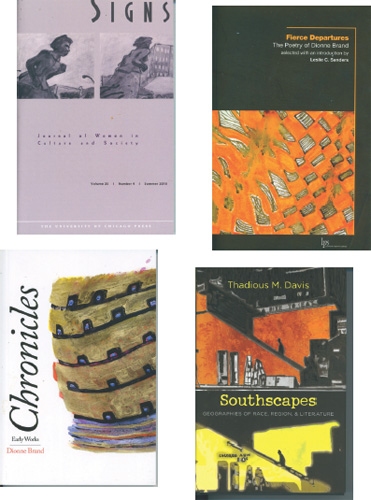

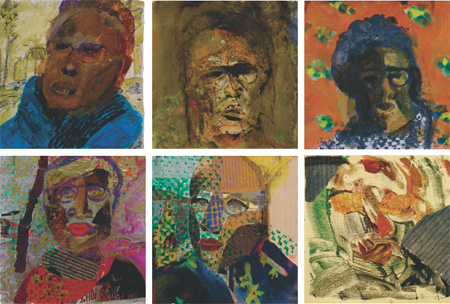

Hey! Not so fast. Not a total failure. One assignment, tapping into my old habit of painting myself, suited my eye and my hand. Sitting at the kitchen table in my apartment, I freely drew, painted, and collaged myself. We were to paint ten self-portraits, 12" × 12". I made twenty-five. I made them on paper and on board, as drawings, collages, and monoprints, in colors bright and subdued. They were all close-ups, but with varied backgrounds: landscapes, patterns, collage, and abstract. Okay. Twenty-five instead of ten of me me me. Best things ever at RISD. Who cares if I’m never An Artist artist?

I have never tried to make my self-portraits look like me, for issues of beauty and skin color and all the other judgment-laden markers of race and gender threaten to trip me up. I’m a nice-looking woman. What does it say if I paint myself as beautiful? My skin is dark. What if I made myself too dark or too light? What even counts as too dark or light?

TOP LEFT: Self-Portrait 3, 2010, acrylic on board, 12" × 12"

TOP MIDDLE: Self-Portrait 5, 2010, acrylic and collage on paper, 12" × 12"

TOP RIGHT: Self-Portrait 10, 2010, acrylic and collage on paper, 12" × 12"

BOTTOM LEFT: Self-Portrait 11, 2010, acrylic and collage on paper, 12" × 12"

BOTTOM MIDDLE: Self-Portrait 12, 2010, acrylic and collage on paper, 12" × 12"

BOTTOM RIGHT: Self-Portrait 16, 2010, acrylic and collage on paper, 12" × 12"

Here lie snares for every black artist, for issues of skin color and nose shape and lip size and thickness and hair texture all carry positive and negative connotations in the aesthetics of race. They aren’t just appearance, not just how things look. Every single line or volume carries social meaning. If I made my lips too thin or my color not dark enough, it could speak a lack of race pride. What about my hair? What a chore to try to depict it in its variegated nappiness, but how to capture it? Every single decision about self-representation could tip me into a racial morass.

My self-portraits wouldn’t be just paintings of a particular individual rendered in a particular painting style. They entered a field of black-woman visual representation encompassing the beauty of Beyoncé and Michelle Obama, in which the light skin of the former fits easily into American tastes and the dark skin of the latter awakens new understandings while also attracting bigotry. “The black body” as minefield.

Black artists have myriad strategies for dealing with “the black body,” for each individual black person’s body, in this case, my own, exists within a visual field of pre-existing imagery, be it negative or positive. I had seen this firsthand with my parents, who were seen differently with the passage of time. And I don’t mean this in terms of age, but with regards to skin color and evolving beauty ideals.

My father had always been considered handsome—still was, deep into his nineties, his light skin according with American beauty standards, his good health and personal charm further heightening his attractiveness. My mother, a different story, and not only because for years she was so shy. Because of her dark skin, my mother never felt beautiful, even though she always was beautiful. Only in her maturity was she widely complimented, due not to a change in her appearance, but to a broadening of American beauty ideals. She was in her eighties when she quoted what people said to her as the title of her memoir: I Hope I Look That Good When I’m That Old. After black became beautiful in the 1960s, my mother’s beauty became obvious. I watched that change, and it inspired my work on physical beauty, manifested in my Michael Jackson and Apollo Belvedere paintings. So, yes, when you see my paintings and my self-portraits, you’re seeing reflections of my mother’s emergence into beauty and my awareness of a nimbus of images and appearances around “the black body,” mine as well as hers. Prominent artists have tackled the challenge of racial expectations in various ways.

Emma Amos and Robert Colescott, two light-skinned African American painters, solved the color conundrum by depicting themselves in their paintings with darker skin to signal their racial identity. Colescott painted himself as dark-skinned in his art history paintings, where a light-skinned figure of the artist would complicate, even obscure their ironic cultural message.

Contemporary artists’ depictions of dark skin avoid mimesis entirely. Toyin Odutola draws with multicolored ballpoint pens so her dark figures shine with countless colors. Amy Sherald, Michelle Obama’s portraitist, paints African American subjects’ skin a flat gray reminiscent of black-and-white photographs. Derrick Adams fragments faces into collage-like blocks of bright, unrealistic color. Kerry James Marshall solves the skin-color conundrum by painting his black figures a dense, matte black to reclaim the “power of blackness.” His paintings are ironic and otherworldly, allegorical rather than naturalistic. Deep black figures in suburban settings transport viewers into an idyllic fantasy realm. Yet this means of rendering dark skin can confuse viewers, can even pique black viewers more accustomed to seeing work in public by white artists, and, given American history, accustomed to seeing black figures depicted in ways that denigrate us.

The traps awaiting black artists can encourage a turning away from figuration. I braved adoring crowds to query abstract painters Julie Mehretu, in Providence, and Mark Bradford, in New Haven. I asked whether the racial politics around depictions of black people played any role in their choices of genre. Both said yes, that by working abstractly they sidestepped controversies of figurative representation that would distract from their art. Mehretu and Bradford do not approach figuration in their painting, and seldom in their titles. Jack Whitten, an abstract painter of great distinction, splits the difference. He captioned an abstract painting Self-portrait, and his titles often refer to black history. I came to painting too late to meet Alma Thomas, who rarely attached political titles to her abstract painting, one reason her work was so hard for such a long time for critics and collectors to value.

HENRY’S CONCEPT OF being An Artist brings me back to ontological thinking, this time about race. You are An Artist in the way you are your race. Both race and art can be envisioned as some quality beyond words that inheres within the person, a quality that can’t reliably be measured. You can be dark-skinned, but still not be black enough. You can have gallery representation but still not be An Artist. It’s more than skin color, more than sales, more than geographical origin, more than gallery representation, more than hair texture, more than collectors. According to this kind of logic, art and race reside in something as slippery as your temperament and the way you perform your identity of black person or artist; you can’t change them, by this common line of thought, for they cannot be taught or learned. Being An Artist has little stable meaning, and its definition and the criteria you use to define it depend, as with race, on who’s speaking to whom, when, where, and for what purpose.

Easy enough for you to say, oh lofty voice of reason. But impossible to hear down here on the ground in the muck and the confusion of the studio and the crit room, down here where An Artist mythology strode the halls as ideal. Impossible to avoid, so just run away.