Okay. My father settled but unhappy in West Orange, New Jersey. Me moving into my own studio in the Ironbound. Newark artist. From home in North Newark, I took my 27 bus to Market Street and walked the opposite direction on Market Street from Aferro, a few blocks east toward and through Newark Penn Station to my studio. I wore work clothes like what I was wearing six years earlier at Mason Gross on that day at Rutgers when I first heard the refrain of my art education, How old are you?

Same clothes, but no question.

On the 27 bus I sat among my fellow Newarkers, but just now seeing Artist Jerry coming on board. As Jerry walked down the bus’s center aisle, I spoke to him from my seat. My greeting brought him into awareness.

I didn’t know that was you, he said.

You blend right in, he added.

And I did blend right in, something I love about Newark. I blend right in. No need to explain my presence or answer questions or present my credentials to prove who I am or justify my being there. I’m not a curiosity or a presence to be appreciated or avoided. I blend right in.

I blend right in. That’s what I said back to Jerry, who gave me a high five right there on the 27 bus on my way to my studio.

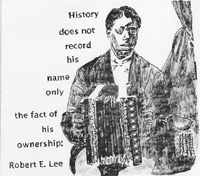

Art in Newark is a nonprofit undertaking dependent on auctions to raise money for worthy causes. One sign you’re a Newark artist is requests to donate your art for auction. I donated a History Does Not print to Aferro for auction, a small black-and-white lithograph inspired by an antebellum photograph of an enslaved young musician with vacant eyes and my comment on the absence of his name. Only the name of his owner, Robert E. Lee, is known. This very plain lithograph worked better as an image than a concept in undergraduate crit, because the students thought the musician’s name must be Robert E. Lee. The Newark Public Library’s Dane Fine Print Collection bought this piece. My first public collection.

History Does Not, 2008, lithograph on BFK Rives paper, 8" × 8"

An artist’s residency in the Newark Public Library let me investigate a little-known, unexpectedly rich visual collection, browsing at leisure as I had in Yale’s repositories. The Newark Public Library can’t match Yale’s libraries, the latter engorged by gifts from the wealthy over centuries. But characteristic of Newark’s institutions, the Newark Public Library has more than you might assume. And the 27 bus stops right there.

There came an emergency call—not about my father, thank heaven—but from the Friends of the Newark Public Library. Glenn and I belonged to the Friends of the Newark Public Library, having joined on moving to Newark from Princeton. I had presented book talks on the Friends’ behalf. This call wasn’t about my books. This was an emergency need to resolve a crisis caused by what would seem great good fortune. Great good fortune complicated by the history of American politics of visual representation. A wealthy New York collector had lent the Newark Public Library a very large drawing by Kara Walker, the famous, legendary, superstar international artist Kara Walker, which the Newark Public Library director had installed, wisely, far from the rooms frequented by children. Indeed, it is a drawing for grown-up eyes.

The charcoal drawing in black and white, reminiscent of Picasso’s Guernica, is huge, truly monumental in its artistry and sheer size, 6' × 9 ½', entitled The moral arc of history ideally bends towards justice but just as soon as not curves back around toward barbarism, sadism, and unrestricted chaos (2010). The title is apt. Beautifully drawn with Walker’s expert draftsmanship, the piece embodies the second part of the title in scenes of atrocity.

A black body lynched over the flames.

Beatings of black people, some naked, some clothed.

A cross burning.

The small figure of candidate Barack Obama delivering his speech on race in America, dwarfed by a naked black figure sucking off a gigantic white man as an older black woman looks on.

Yes, these are recognizable scenes from the iconography of American history. At the same time, this is not an assemblage to make you feel good about being black. It’s more a reminder to white people that American history is more than Diarylide-yellow enterprise and democracy in viridian green.

Revolt ensued.

One of the Newark Public Library’s librarians, an organizer who had convened meetings of Newark artists that I had attended, told the Newark Star-Ledger,

It can go back where it came from. I really don’t like to see my people like this.

She had a good point, and she spoke for masses of African Americans who needed to see something less distressing. Once again, art-world enthusiasm confronted African American tastes. The Newark Public Library worker expressed what so many had so deeply felt for so long, that black people had been cruelly stereotyped as stupid and ugly, when not exiled entirely from American visual culture, that we needed to see not more ugliness, but a corrective that showed our beauty.

In the face of uproar, the Newark Public Library director had panicked, covering the drawing with a drape. Obviously, in an institution serving a majority black city, a large work by a major black artist could not remain shrouded. To deal with the crisis, the Friends of the Newark Public Library called an emergency session. We talked to Kara Walker.

Kara Walker to the rescue!

She came to Newark with her images, her assistant, her gallerist, and her gallerist’s assistant, all without charging the Newark Public Library a cent. A cent the Newark Public Library didn’t have but would somehow have found if necessary. Walker sat with me on a raised platform in Centennial Hall to show her work and answer first my, then the audience’s, questions, the audience, rapt, overflowing, and full of Newark artists thrilled to be in the presence of so renowned an artist. Walker charmed Newark artists who were already her fans. Artists, after all, were not protesting her work. Artists weren’t her critics.

She showed slides of the drawing as she made it in her studio as part of a larger exhibition, Dust Jackets for the Niggerati. Walker spoke softly—she said she felt a little anxious. She explained that her work expressed the “too-muchness” of race in America. When she said her images of racial terrorism “should be horrible to behold” and “should feel both familiar and uncomfortable,” was she thinking of black viewers? I don’t know that she convinced those hungering for something uplifting. After Walker’s visit, the drape came down.

IN THE FALL I had another residency, at Yaddo in Saratoga Springs, New York, where I resumed the Odalisque Atlas I had begun at Yale in the spring before my father’s needs superseded my own.

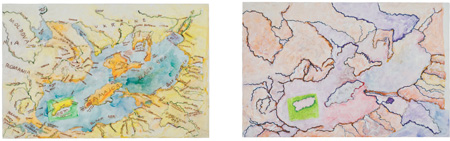

Maps have always intrigued me as visual images and as representations of human and geographical presence. They depict at once physical space and cultural significance. At Yaddo I used my atlas to draw regions of enslavement on tracing paper, arranged them according to my plan, and scanned the assembled tracings as an imaginary geographic template. Most of the tracing paper disappeared in the scan, but the rectangle around Puerto Rico showed up, purely an artifact of my process. Liking the way it looked, I kept it in my paintings. Viewers could interpret its meaning as they wished, especially if their roots lay in Puerto Rico. It could be a cobalt-green rectangle as a green rectangle or a cobalt-green rectangle of Puerto Rican innuendo. I forgot to show Cuba, an oversight that also prompted political interpretation.

I projected the template on 26" × 40" sheets of Yupo, traced the projection in charcoal, and applied acrylic paint and ink thickly on some and thinly on others. I painted eight maps that contrasted visually, though all derived from the same template. One looked like it might be a real map, with local names in the right local places, but the places where slave girls came from jumbled together. Haiti scrunched up by Crimea. Thailand abutted Russia and Ukraine. New Orleans and the Mississippi River delta stuck out into the Black Sea. West Africa turned around to face east. Istanbul lay near Moldova. The Caucasus occupied a prominent place at the top. One map in whited-out color had no place names. Place names on another bore no relation to actual geography, so that the rivers on the turned-around shape of West Africa bore European names. One map was splotchy angry red and blue. Two were gray, with textures I made with different kinds of erasers.

LEFT: Black Sea Composite Map 4 Historic Map, 2012, acrylic on Yupo, 26" x 40"

RIGHT: Black Sea Composite Map 7 Washed Away, 2012, acrylic on Yupo, 26" x 40"

With a freedom unavailable to me as a historian, my imagination was feeding off history that I had written. After my eight maps, I turned to two new paintings, repeating a figure I took from a New Orleans brothel photograph in the Beinecke. The backgrounds of these two paintings were from detailed maps, one of West Africa, one of the Caucasus. I was relishing my work, savoring it as a kind of secret pleasure, for I still lacked confidence in my own eye. If I liked something I had made, I couldn’t be sure it was truly any good.

So dumb to still be so insecure! One evening in the library (the only place with internet connection), I confessed to Richard, another Yaddo guest—at Yaddo, residents are called “guests.” Richard was a composer nearly as old as me, but with a long list of prestigious achievements befitting his age. The world had listened to Richard’s work and applauded it. In the library I confessed to him that I had asked a more experienced artist friend to stop by and look over my new work on her way up to the Adirondacks. She could tell me if my Odalisque Atlas was actually okay. Or not. I was so fucking self-doubting.

Richard of the long experience and impressive achievements made a confession of his own:

I’m still insecure.

Now that was good to hear.

My artist friend rightly skipped Yaddo, leaving me to trust my own eyes. Eventually that trust crept into me. Eventually. But more as I-don’t-care-if-this-is-good-or-not-I-like-it than as certainty as to the objective value—objective value?—of my work.

RIGHT THEN THE longtime partner of my Dear Cousin Diana called me from Oakland. Devastating news. Diana had liver cancer. Liver cancer kills, kills fast. It would kill her before my next visit to the Bay Area. And now, with my father in New Jersey, when would that be? If I wanted to see Diana alive, I would have to suspend my work and leave Yaddo to go see her now. Once again, family won out over art.

But there was no going to see her now, as Superstorm Sandy shut down air travel. I was stuck; Diana was dying. I spoke to her by phone, both of us choking up, both of us crying. She said she really wanted to see me, with an emphasis stronger and deeper than the usual afternoon visits I would pay her whenever I was in Oakland. This wasn’t whenever-you’re-in-Oakland. This was now. She really wanted to see me urgently. This meant now. A now feeling more urgent than my father’s nows, which belonged to a series. Please, Diana, hold on. Hold on. Diana’s now would expire.

I felt that now, that impending ending as a muddy gray mashing down, the green-tinged brown on an unwashed palette, the same heaviness as in my mother’s death. Diana’s dying seemed like my dying, too.

Growing up we had been like sisters, close in age—she a little older—and sharing much of the looks of my father’s mother’s side of my family, but not his pale skin. Same braids. Same composed expression. My parents drove us around California with the abandon of southerners finally allowed the freedom of the out-of-doors that had been denied them in the South. California was ours, experience was new, and we drove all over. Both generations experienced California with the freshness of first time, before repetition and familiarity dulled the edges of our delight. As adolescents, Diana and I diverged. We became less sisterly while remaining close cousins. She went to Hayward State. I went to Berkeley. I visited her every time I came to California, year after year.

Stuck at Yaddo until the Superstorm passed and I could travel, I called my friends and cried to them for consolation. Finally in California, I sat with Diana in convalescent care, where a woman down the hall cried out ceaselessly, Help me! Help me! Help me! Diana, weakened and in pain, was not yet moribund, but I saw death coming for her. This took her partner totally and unaccountably by surprise. He was determined she would recover, and, bent on recovery, he refused her hospice care. Shortly after I departed, Diana died, hooked up to machines intended for cure.

My return flight east traced, no, retraced, a gorgeous transit I had made countless times over nearly countless decades, over the Phthalo-blue San Francisco Bay, over the yellow ochre hills of the Coast Range, over the Jenkins green fields of the Central Valley with its aqueducts, over the now sepia, not yet nevada-snowy Sierra Nevada to the arid neutral gray flats of Nevada where you can hardly see any roads.

From the Bay to Nevada I wept over losing Diana, the sister of my girlhood, and the shutting down, the closing out of even the memory of my youth in my hometown and home state. When Glenn remarked to my father on leaving after seventy years, I had sensed an ending, but as more a thought than a sensation. I had become the parent of my parent, and I was bringing him home to me. His was an ending, yes, but an ending as a transition opening to a continuation elsewhere and in that way an opening to something new.

Losing Diana meant an ending as transition only in that New Age denial of the finality of death. My ending flying over California this time leaving Diana did not open onto new. This was chopping off a root, the closing down of the time when I was learning my way around for the first time, not as the constant readjusting of age to keep up with change over time, a severing of the connection to the personal deep past of my geographical history.

FROM MY YADDO residency I took a yield of eight maps and two paintings of my Odalisque Atlas. My early years as a painter, in Providence, New Haven, and Saratoga Springs, felt as much about family and loss as about art making. But how else could it be for a grown-up with a grown-up’s attachments? After a certain age, you’re responsible for your family, and family means crisis; family means loss.

BACK IN WEST Orange, New Jersey, I was reading my father Toni Morrison’s new novel Home. He was praising it, savoring Morrison’s language, following her plot. Then he weakened. Suddenly he couldn’t sit up in his wheelchair or keep his eyes open. Uh-oh, he was sinking. He had seemed terminal before, actually several times before. But he had always bounced back. Still, I had never before seen him this unresponsive. I fetched the nurse to check on him, and she called hospice. Someone would come the very next day.

The hospice nurse came the next day, but, she said, she couldn’t find the right room. The man in the room she’d been sent to was sitting at his table eating peanuts. Wrong room? Wrong person? No. That was my father at the table eating peanuts. He was back in life again.