A DEFENSE OF HISTORY

As instructed, the Assistant arrives at the campus library early on Friday. This despite not being what one would call a morning person. He needs coffee ASAP, which makes his location convenient. Among undergrads, the library is more commonly and aptly referred to as “the place where Starbucks is.” He shivers in November’s autumnal chill as he waits for the Historian, a professor in the department where he is pursuing his Ph.D., the one who has beckoned him here at this early hour, the attractive older woman upon whom he has the most innocuous of crushes and whom he hopes will guide his own studies when he’s ready to dissertate in a couple of years. Still finishing his coursework, the Assistant was appointed to help her with research this semester, a post that until now has mostly entailed tracking down a few articles for her book project on the People’s Party.

“Populists,” she said when they met in her office back in early September to discuss her research. “Radical agrarians. You’re familiar?”

The Assistant learned quickly that in this environment there is nothing worse than showing intellectual uncertainty, and nodded with a confidence that wouldn’t, on pain of death, betray the fact that he had no idea what she was talking about. Afterward, waiting in the interminable line at the bookstore to purchase texts for his classes, he took out his smartphone.

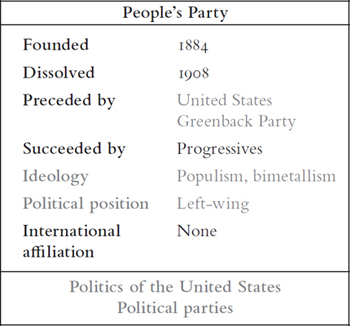

Populist Party (United States)

The People’s Party, later erroneously also known as the Populist Party (derived from “Populist” which is the adjective which describes the members of this party) was a short-lived political party in the United States in the late 19th century. It flourished particularly among western farmers, based largely on its opposition to the gold standard. The party did not remain a lasting feature most probably because it had been so closely identified with the free silver movement which did not resonate with urban voters and ceased to become a major issue as the U.S. came out of the recession of the 1890s. The very term “populist” has since become a generic term in the U.S. for politics which appeals to the common in opposition to established interests.

—WIKIPEDIA ENTRY, 2010

The research has been interesting and his duties minimal, but yesterday he received an e-mail from the Historian asking if he was going to be around this weekend and whether he might be able to help with her research at the library. There was urgency in her tone, a faint allusion to an imminent deadline of sorts. He’d planned to drive the two hours home to spend a long weekend with his parents. His mother is sick and has been undergoing treatment throughout the summer and fall, something he’s avoided facing since school started up, and the Historian’s request gave his continued avoidance an air of legitimacy. “Of course we understand your school obligations,” his dad said, clearly bummed, when the Assistant called to cancel. “I’ll give Mom your love.”

When the Historian arrives, they enter the building through the slow-sliding automatic doors, purchase coffees, and take the elevator to the fifth floor, where they find an empty conference room. The Historian is slim and fit, an obsessive user of a personal home Elliptical, the Assistant would wager. Her hair is red, cut short, textured, and styled messy, and her face has an angularity that gives her a hint of masculinity that makes her seem both sexy and fierce. If she made a pop album, it would be called Sexy/Fierce. Instead of a backpack or briefcase, she tows behind her a roller bag too large for overhead stowage in an airplane. It makes her seem older than she is—mid-forties, he’d guess, but clearly passes for late thirties. He helps her lift her luggage onto the large, rectangular table. “This is my war room for the weekend,” she says, unzipping the bag to reveal stacks of yellow legal pads tattooed with blue ink, as well as books from her home and office.

Properly caffeinated, the Historian lays out the game plane. Her book proposal on the Populists is due on Monday. She has three days to figure out her angle on these radical farmers and work up a pitch. She wants him to focus on primary sources today, to see if he can’t find something interesting, something she’s overlooked. “Take notes on anything that seems relevant,” she says, tossing him a clean legal pad. Relevant to what? he wonders. He takes it and puts it in his messenger bag. “Transcribe, make photocopies if necessary.” He stares at her, faintly nodding, waiting for more direction. He’s unsure where to begin, but too embarrassed to say he’s unsure where to begin. “This is good training for your own research,” she tells him, ushering him out of the room with a powerful little nod toward the door. “I’ll be in here if you need me.” As he makes his way down the hall, he hears the Historian call out, “Thank you!”

The time has come when it is necessary in our own defense that the working people of this country, the farmers, mechanics, day laborers and all men and women who earn their living by hands or brains, organize against usurpation. . . . This is not a movement against the merchant, the lawyer, the beggar or anyone else, but a great uprising of the people. They say we want to destroy capital. But we want to restore the supremacy of the people, and we propose to do it.

—WILLIAM PEFFER, POPULIST SENATOR, KANSAS, 1891

Equal rights for all and special privileges to none.

—SLOGAN OF THE PEOPLE’S PARTY, 1891

It’s been a little while since he’s considered the matter, so the Assistant recounts what he knows. In the decades after the Civil War, farmers were crippled by agricultural debt, and by the 1880s the country was deep in recession. They organized alliances in the South and Midwest to press for economic relief and governmental reform, but the Democrats and Republicans did little to alleviate the situation of the farmers. The grassroots push for an independent third party that would do something grew rapidly, spurring the formation of state parties that won major electoral victories in 1891, as in Kansas, and within a year the national People’s Party was founded. The Assistant wonders how he’d never heard of the Populists before. His entire life spent in the state and it took coming here to Manhattan, Kansas, to the state’s agricultural college, to find out about them. How does that happen?

I am the innocent victim of a bloodless revolution—a sort of turnip crusade, as it were.

—JOHN JAMES INGALLS, REPUBLICAN SENATOR, KANSAS, UPON HIS DEFEAT BY POPULIST WILLIAM PEFFER, 1891

And I say now to you as my final admonition, not knowing that I shall meet you again, raise less corn and wheat, and more hell.

—MARY LEASE, KANSAS POPULIST,

ADDRESSING A GATHERING OF FARMERS, 1891

For nearly five decades the Assistant’s grandfather, who considered himself an Eisenhower Republican, was a farmer in western Kansas. He died when the Assistant was young, but from what he remembers he could never imagine his grandfather raising less wheat and more hell. The Assistant feels drowsy, could use a little break, so he picks up another coffee, exits the library, and calls home to see how his mother is doing. She’s in partial remission and there’s constant fear and likelihood of recurrence. Throughout the awful summer, he’d driven her to appointments and sat in waiting rooms and worried, while at home he’d read to her from her favorite chapters in the Bible. All the while she grew frailer and frailer but her optimism and fortitude didn’t diminish the way the Assistant’s had. That was what was tough to face: her equanimity in the face of it all. It was either denial or acceptance, and both were unsettling because they led to the same end.

The Assistant’s father answers the phone and tells him that Mom is resting, so the Assistant asks about Grandpa, the farmer. “Dad was a man full of contradictions,” says the Assistant’s father. “He hated farming but did it anyway. He lobbied for and relied upon government subsidies that kept his farm afloat, and then voted a straight Republican ticket each election.” The Assistant asks if he’s ever heard of the People’s Party. “The what?” his father answers. “Is that some new commie outfit on campus?” The Assistant tells him he needs to get back to work.

It’s only right that the Conference come at the call of Kansans, for on her plains was shed the first blood in the struggle that freed six million slaves, and on her soil was fought the first battle which is to free sixty-three million industrial slaves.

—WILLIAM F. RIGHTMIRE’S OPENING REMARKS AT THE CINCINNATI CONFERENCE THAT WAS TO CREATE

THE NATIONAL PEOPLE’S PARTY, 1891

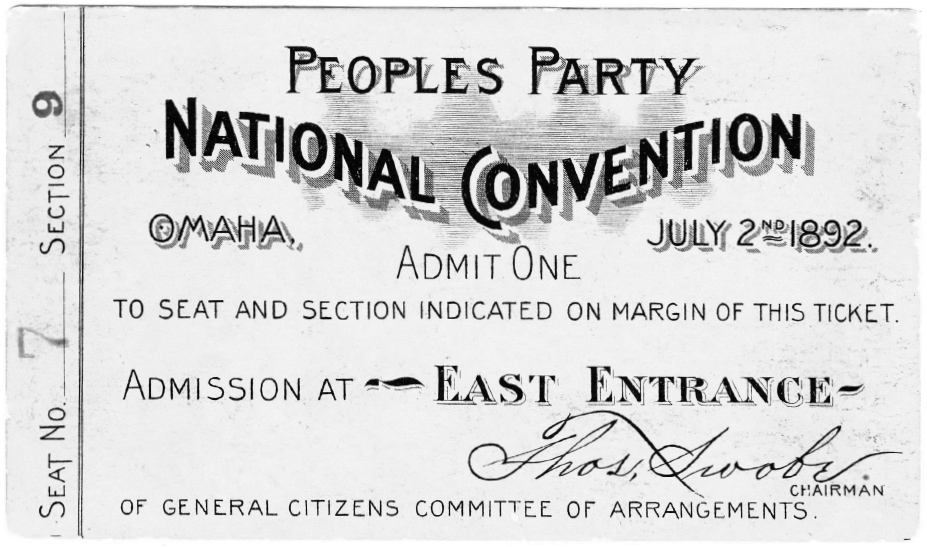

The Assistant feels a slight preference for the yellow highlighter over the green. He studies a Xerox he’s made of the Omaha Platform, the Populists’ first unified statement of their policies and beliefs. Wealth belongs to him who creates it, he highlights. The interests of rural and civic labor are the same; their enemies identical. Their platform called for government control of transportation and communication: The time has come when the railroad corporations will either own the people or the people must own the railroads. They also demanded the direct election of senators, an eight-hour workday, a progressive income tax, and the free coinage of silver to create a more flexible currency that would protect farmers from inflation and debt. The land, including all natural sources of wealth, is the heritage of the people and should not be monopolized.

Just then the Assistant realizes the Historian is looking over his shoulder. “The Omaha Platform,” she says. “My God, isn’t it beautiful?” The Assistant opens his mouth and the Historian raises a hand to stop him. He wants to ask what exactly it is he’s supposed to be looking for. “Just going to pee,” she whispers, walking away from his table. “Carry on.”

The new movement proposes to take care of the men and women of this country and not the corporations. This movement is a protest against corporate aggression.

—POPULIST PRESIDENTIAL CANDIDATE JAMES BAIRD WEAVER, 1892

I have no qualms of conscience about commanding the corporations of the country to obey the law, they are the creatures of the law; all that they have the law gives to them; and the people of this country, especially the farmers and the workmen, have been trampled upon by these railway corporations until they are crying out in despair almost.

—WILLIAM PEFFER, POPULIST SENATOR, KANSAS, 1893

A movement against unchecked corporate power in the 1890s? Fittingly, the Assistant ponders that as he waits in line for another coffee at Starbucks. As a twenty-seven-year-old man in 2010, he sometimes feels like they, corporations, are some modern phenomenon unique to his personal life chronology, like MTV or the Internet.

While the Populists lost the national election of 1892, they did garner eight percent of the national vote and won four states outright, the Assistant learns, making their showing kinda phenomenal considering the party was less than a year old. And here in the Kansas state elections the Populists made even bigger gains, electing their entire state ticket.

It is the mission of Kansas to protect and advance the moral and material interests of all its citizens. . . . The grandeur of civilization shall be emphasized by the dawn of a new era, in which the people shall reign; and, if found necessary, they will “expand the powers of government to solve the enigma of the times.”

—KANSAS GOVERNOR LORENZO D. LEWELLING, INAUGURAL ADDRESS, 1893

We have come today to remove the seat of government of Kansas from the Santa Fe [Railroad] offices, back to the Statehouse where it belongs.

—“SOCKLESS JERRY” SIMPSON, POPULIST CONGRESSMAN FROM KANSAS’S SEVENTH DISTRICT, 1892

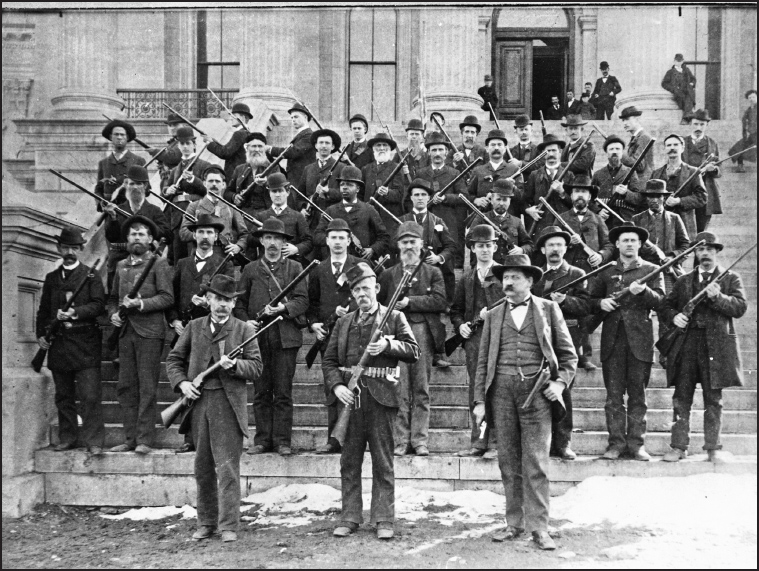

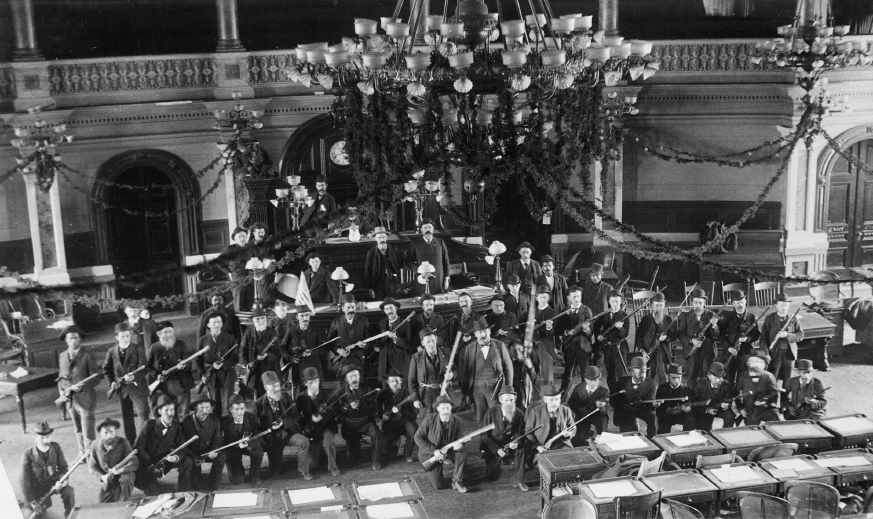

Late in the afternoon, the Assistant comes across the story of an incident he’d never heard of before called “The Legislative War,” one so unbelievable he literally writes WTF? in the margins of the book where he found it. According to this account, it was perhaps the only attempt ever made in this country at “social revolution in the classic sense: violent seizure of the apparatus of government accompanied by class warfare in the streets.” The conflict was between the Republicans and Populists over contested election returns that would decide the balance of power in the Kansas statehouse in 1893. Neither side gave ground, and for more than a month the legislature was a divided body, with Republicans using the chamber in the morning and the Populists in the afternoon. Little was accomplished and frustration grew as threats issued from both sides, until finally the schism led to armed conflict. The Populists locked the Republicans out, and the Republican speaker of the House used a sledgehammer to break down the doors and gain entrance to the chamber. Fistfights broke out on the House floor, while outside members of both parties armed themselves. Populist governor Lorenzo Lewelling sent in the militia to restore order, declaring: “We are here by the will of the people and will disperse only at the point of the bayonet.” The hostilities went on for days.

What is an almost-revolution like? the Assistant wonders now, looking away from the machine where he examines old newspapers on microfiche. A fleeting vision: he is marching with the disquieted masses, storming the capital in expropriated SWAT gear. There is urgency and anger. Fists are raised. A grappling hook might be involved.

“ANARCHY!”

“ANARCHISTIC!”

“THE JACOBINS!”

“Is the Kansas Trouble the Incipiency

of a National Anarchist Uprising?”

—February headlines from The Kansas City Mail,

The Wichita Daily Eagle, The Marion Times,

and The Kansas City Gazette, 1893

It appears to be the determination of the opposing factions in the Kansas House to superadd to the stupidity of a senseless deadlock the crime of an open revolution.

—KANSAS CITY STAR, 1893

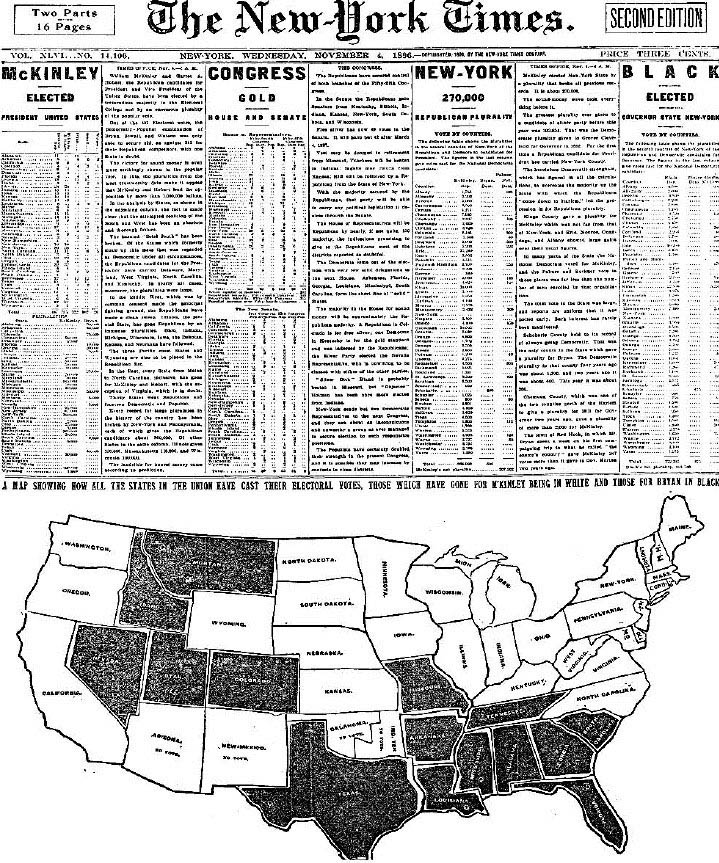

When things calmed down, however, the upstart Populists were blamed for the affair. This was the beginning of the end for the party, the Assistant learns. Though they would win state elections in Kansas in 1896, it was the national election of that same year that would prove fatal.

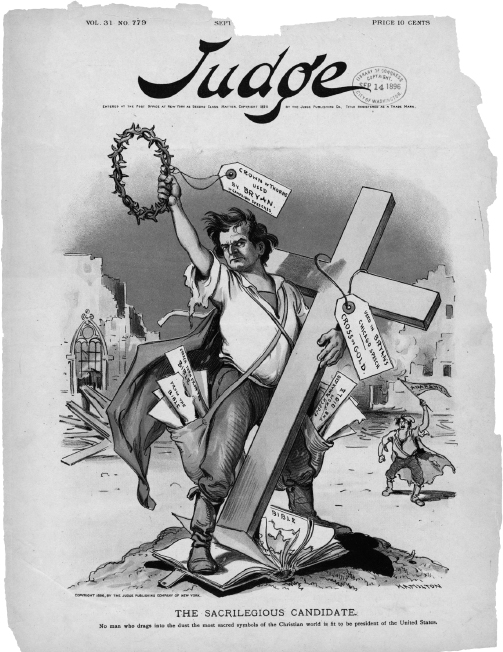

While the party’s numbers had increased sharply in a few short years, Populist strength was largely concentrated in regional pockets of the South, Midwest, and West. Without additional support, which meant merging with one of the major parties, it would be impossible for them to have a chance of winning a national election. And so it was that the issue of silver, a minor plank of the Omaha Platform, became the central issue in the debate over fusion. The People’s Party advocated bimetallism, the use of gold and silver as currency, to increase the money supply and alleviate the debt farmers and the poor had taken on throughout a decade of economic depression. The pro-gold financial elite in the Northeast, who were also the creditors for most of the country’s debt and benefited from staying on the gold standard, supported the Republicans. The Democrats, backed by silver mine owners in the western states, decided to make the free coinage of silver a central issue in the presidential election in an effort to win Populist support. Their young charismatic presidential candidate, William Jennings Bryan, electrified many with his fiery rhetoric.

Having behind us the producing masses of this nation and the world, supported by the commercial interests, the laboring interests and the toilers everywhere, we will answer their demand for a gold standard by saying to them: you shall not press down upon the brow of labor this crown of thorns, you shall not crucify mankind upon a cross of gold.

—WILLIAM JENNINGS BRYAN, 1896

Is the Populist party ready to be dumped into the lap of [the Democrats]? Are the men who have been fighting the battle of humanity in this country for twenty years willing to acknowledge all they wanted was a change in basic money? Are we ready to sacrifice all the demands of the Omaha Platform on the cross of silver?

—ABE STEINBERGER, KANSAS POPULIST, 1896

If Populism means nothing more than free coinage of silver, there is no excuse for the existence of such a party.

—WILLIAM PEFFER, POPULIST SENATOR, KANSAS, 1896

The party that was going to pay off all the debts of the people by legislation, that was going to even up the inequalities of life that come from inequalities of the brain, the party that was going to stop the smart man from getting the best of the stupid chump, the party that was going to do what God himself couldn’t do—make men equal. . . . And all that is left of this great nightmare is a roomful of sad visages, seedy citizens and a terrible past.

—WILLIAM ALLEN WHITE, REPUBLICAN NEWSPAPERMAN FROM EMPORIA, KANSAS, 1895

After Bryan lost to William McKinley in 1896, the People’s Party ceased to be relevant at the national level. The Kansas Populists were voted out of office in 1898, and by 1900 most had either given up on politics or become Socialists. In the ensuing decade much of the Populist platform was either enacted or on the way, championed by the very Republicans, rebranding themselves as Progressives, who’d opposed them initially.

We caught the Populists in swimming and stole all their clothing except the frayed underdrawers of free silver.

—WILLIAM ALLEN WHITE, REPUBLICAN TURNED BULL MOOSER, 1940

I met some of my old Republican opponents today and they said to me: “Oh, Jerry, you ought to be in Kansas now. Kansas is all Populist now.” Yes, I said to them, you are the conservative businessmen of the state, and doubtless all wisdom is lodged with you, but you are just learning now what the farmers of the state knew fourteen years ago.

—“SOCKLESS JERRY” SIMPSON, FORMER POPULIST CONGRESSMAN, KANSAS, 1905

The Assistant keeps at it all afternoon and into the evening, occasionally catching sight of the Historian walking somewhere with extreme purpose or scribbling furiously on a legal pad. He’s been so wrapped up that he’s forgotten to eat lunch, and with the dinner hours nearing he’s tired and ravenous. When a voice comes over the PA to tell them the library will be closing in fifteen minutes, the Historian appears.

“What the hell kind of university library closes at six?” she says. “In my day they were open all night—you could bunk up with a transient if you wished.”

“Sounds great.”

“It was! I got so much work done.”

He follows her to the conference room down the hall where she packs up her absurd luggage, and they walk toward the elevator. On the ride down, his stomach makes increasingly loud thundery sounds, which both agree tacitly not to acknowledge.

“How did it go today?” she says as they exit the library.

“Good, I guess, but I don’t really know what I’m looking for.”

“You’re doing the right thing. I just want a lot of source material to consider once I figure out my argument. It’s bound to click soon. Usually it comes out of nowhere. Who knows, maybe it’ll hit me on the walk home.”

She turns to leave, saying she’ll see him tomorrow. She lives close to campus, the Assistant thinks as the Historian and her bag roll away. He wonders what her house is like and for a brief moment considers following her before deciding that’s an absolutely terrible idea. He returns to his apartment to supper on Hot Pockets and Sunny D, the dinner of folks everywhere who don’t even compete in the race, but it’s been a long day and, well, so what if he likes his Hot Pockets. He plops onto his futon, which is employed permanently in its couch function because it’s broken, and turns on the TV, which gets a single, fuzzy channel. Through the garish swirl of bad reception he can just make out a detective show of some sort, which he watches semi-awake, followed by another detective show of some sort—a spin-off of the first perhaps—before the late local news comes on. During his time in graduate school he’s become a lazy citizen, neglectful of affairs local and otherwise. He has a general sense of things, overhearing bits of conversation at school, ignorantly uh-huhing as one of his parents references some incident or other. But mostly, as they say, he’s fallen out of the loop. Sometimes on the phone his mother will ask, “Do you live in a cave or something?” and he’ll look around his three-hundred-square-foot apartment at the stacks of books and mounds of dirty clothes and consider answering in the affirmative.

Tonight there’s a story about a massive Tea Party rally in Washington against the expansion of health care. He actually has heard about this, thanks to good ole Dad’s middle-age flirtation with libertarianism, his father’s love-hate relationship with the Republican mainstream. Sitting on the coffee table next to a half-empty Sunny D is the legal pad he took notes on today. He picks it up and begins to doodle absentmindedly as he listens to the TV. It’s strange when the newscaster uses the term populist movement in reference to the Tea Party, these people whose rage seems both real and subsidized by billionaires. They are the complete opposite of the Populist Movement the Assistant has spent the day researching that wanted to use government to help the rural and urban working poor at the expense of the rich and corporations. These small-p populists seem to want to destroy government to protect Big Business at their own expense. Oh, and personal freedom, that’s a big deal for them. From their cold dead hands or something. No, that’s guns, which is also apparently about personal freedom, so maybe it is the same thing. He’s heard all the Tea Party talking points from his dad, and the Assistant listens quietly, not bothering to voice suspicion of his freedom to be uninsured, that opportunity to accrue massive and insurmountable poverty-trapping debt in future visits to the ER if he so chooses—second only perhaps to the poor’s sacred freedom to starve.

Actually, once he didn’t listen quietly. Once this summer, in fact, when his mother had just come home from the hospital and his father was ranting at clips of the president on TV, the Assistant said, “What about Mom? What if she didn’t have insurance? What if you all had to take on the debt of her surgeries and treatment and medication?”

“You leave Mom out of this,” his father had said. “Don’t you dare make this personal.” And then Dad went ahead and made it very personal: “Say we actually had national health care. Do you know what would have happened if Mom didn’t have surgery right away? If she had to wait weeks or months in line behind others?”

They’d caught the disease early, but it was an aggressive form, and his dad had taken her to Kansas City immediately, to the best treatment center in the region. While his father did not analogize the situation to those new barroom jukeboxes he’d seen in some of the bars near campus whereby one can pay more money to cut to the front of the song queue, the Assistant’s mind went there immediately. No, there was no mention of line-cutting, let alone the fifty million people not even allowed to wait in line at present, and yet the terrible thought of Mom languishing there as the disease consumed her insides did penetrate the Assistant like a lance through the chest. Mom. The Assistant sets the legal pad aside and thinks of calling home, but the clock on top of the TV that he’s never properly reset after last month’s power outage says it’s 3:17 p.m., which means it’s 10:32 p.m., much too late to phone.

The next morning the Assistant makes his way back to the library. Still half-asleep, he notices clusters of purple-and-white-clad students staggering around campus. One young man is literally army-crawling across the quad in purple overalls. What is going on? There’s something of a zombie apocalypse about the scene. Maybe this is a dream. But then it hits him: home football game! The Assistant has never been up early enough on a Saturday to actually witness this, but here he is in the midst of ritual. In Manhattan, Kansas, two things are sacrosanct: football and farming.

The library has just opened and the Assistant figures the Historian might already be in the war room, but when he arrives at the fifth-floor conference room he finds someone else there: a young female student sitting at the head of the table before her laptop, wearing headphones and giggling. She has on pink sweatpants tucked into furry winter boots as well as a men’s undershirt, as if the bottom half of her were prepared for winter while the top was still summering. Oh hell no, he thinks. He stands in the doorway until she looks up from the computer screen to take notice of him. He switches his messenger bag from one shoulder to the other, meaning: Do you know who the fuck I am? She goes back to watching her dumb show or dumb movie or whatever the hell it is she’s watching, but the Assistant just stands there glowering until finally, vanquished, she rises, unplugs her power cable from the wall and brushes past him, refusing to close the laptop, which she bumbles awkwardly as she relocates to a common area down the hall. The girl is rail thin, but the seat of her sweatpants says Juicy in cursive, which is strange, but also better than having Fat Ass written across your butt, whatever its actual size, he concedes.

When the Historian arrives, the Assistant wants to tell her how he defended her honor, or protected their turf, or drew a line in the sand, but can’t find the right bromide and lets it go. They’ve got work to do anyway. She’s dropped the sexy-fierce pantsuit of yesterday in favor of snug blue jeans and a well-worn Liz Phair concert tee from the early nineties, which is sexy in its own way. Sexy-casual. He wants to ask how her walk home was yesterday evening, whether the idea came to her, but he can see she’s agitated and there’s little time to waste with pleasantries.

“You’re on secondary sources today,” she says.

“Okay.”

“You can start here.” She motions toward The Bag, which somehow seems to have put on a few lbs. since yesterday.

“Okay.”

“But you might also run a search, check the databases, and see if anything interesting turns up.”

“Okay.”

Her directives still sound a little like “Go walk around for several hours and write down everything you see,” but he’ll do his best. The Historian unloads books from The Bag and pushes the stack across the table slowly toward him. The books at the top skirt the edge, about to fall, but stop, leaning precariously, as if held there by some unseen wad of chewing gum. A biblio-Pisa. He decides he’ll work in a carrel near the computers and takes the books low into his arms and clamps his chin on the top to steady them for the hazardous walk down the hall. “We’ll meet up later and see where we stand,” the Historian calls after him, a command the Assistant can acknowledge only with the slightest turn of his head.

Kansas was probably the most radical state in the Union in the 1890s, and leftwing efforts continued there for decades.

—WILLIAM C. PRATT, “HISTORIANS AND THE LOST WORLD OF KANSAS RADICALISM,” 2008

The Populists in Kansas, however, were never successful in uniting the rural with the urban political elements. . . . The agrarians, in their struggles against bankers, railroads, mercantile interests, and sound money men, held little appeal to the average urban workers who confronted quite different problems and adversaries. . . . The Populists, however, left a good legacy of labor legislation despite workers failing to reciprocate with political support for agrarians.

—R. ALTON LEE, FARMERS VS. WAGE EARNERS: ORGANIZED LABOR IN KANSAS, 1860–1960, 2005

Parry, parry. Riposte:

Populism was never just a farmers’ movement, even in its earliest stages, and agrarian radicalism always encompassed more than just farmers whether they be “subsistence yeomen” or “petty producers.” And I do not think farmers would have accomplished nearly as much as they did had the movement been limited to farmers from the beginning.

—O. GENE CLANTON, A COMMON HUMANITY: KANSAS POPULISM AND THE BATTLE FOR JUSTICE AND EQUALITY, 1854–1903, 2004

The Assistant’s carrel is overrun with small, variously colored sticky tabs that he uses to note passages the Historian might find helpful. He discovers a yellow tab affixed to his coffee cup. Mysteriously, too, one on a neighboring chair. Colored red.

In their struggle, Populists learned a great truth: cultures are hard to change. Their attempt to do so, however, provides a measure of the seriousness of their movement. Populism thus cannot be seen as a moment of triumph, but as a moment of democratic promise. It was a spirit of egalitarian hope, expressed in the actions of two million beings—not in the prose of a platform, however creative, and not, ultimately, even in the third party, but in a self-generated culture of collective dignity and individual longing. As a movement of people, it was expansive, passionate, flawed, creative—above all, enhancing in its assertion of human striving. That was Populism in the nineteenth century.

—LAWRENCE GOODWYN, THE POPULIST MOMENT: A SHORT HISTORY OF THE AGRARIAN REVOLT IN AMERICA, 1978

The interpretative volleying of historians. The Assistant recalls his father’s fondness for saying that opinions are like assholes: everyone’s got one.

The interpretations of Populism have run a considerable gamut. John Hicks’s Populist Revolt (1931) saw it as interest-group politics using popular control of the government and government action to regulate corporations and political conspiracy. Chester Destler in his 1946 account de-emphasized the regional aspects and saw the People’s Party as part and parcel of long-held radical beliefs on natural rights. . . . Robert McMath, in American Populism: A Social History (1993), emphasized that Populism was especially strong in Kansas because the mainstream party response to farm problems was ridicule and intransigence. Had there been some bend in the Republican establishment, perhaps there need not have been such a fracture. Worth Robert Miller has found the picture still not orderly after one hundred years of analysis. . . . The movement does not fit neatly into a standard ideological category. Miller concluded, “It was a thoroughly American, nonsocialist, anticapitalist movement that called for enough change in the institutions of land, transportation, and money to be considered moderately radical.”

—CRAIG MINER, KANSAS: THE HISTORY OF THE SUNFLOWER STATE: 1854–2000, 2002

He wonders what angle the Historian will take.

The Assistant, spitballing: Populists as some kind of anti-agribusiness/sustainable-farming avant-garde? Possible title: Organic Revolution.

A study of populist outrage: the People’s Party and the Tea Party? Possible title: Grassroots vs. Corporate Roots.

Then the Assistant comes across this:

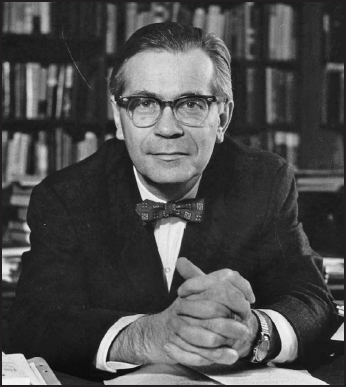

The grievances and solutions articulated by the People’s Party have been the source of much historiographical conflict. In the 1950s Richard Hofstadter portrayed the Populists as an assortment of angry, reactionary rustics, dreaming of preindustrial times rather than facing the permanence of recent changes. Others found the Populists a far-sighted group of reformers concerned with America’s industrial future.

—THOMAS FRANK, “THE LEVIATHAN WITH TENTACLES OF STEEL: RAILROADS IN THE MINDS OF KANSAS POPULISTS,” 1989

Which rings a bell from earlier research. Hofstadter, the name keeps coming up. The Assistant scans the H columns of the indexes in the books on his desk.

Hofstadter was no specialist on Populism, but his treatment in this book changed the direction of scholarship on the topic. No other account had such an impact on the study of farm movements. He explored the darker side of populism, focusing on its illiberal tendencies. In his eyes, Populists indulged in conspiratorial thinking, nativism, and anti-Semitism. The Age of Reform won the Pulitzer Prize for History in 1956 and, to this day, is acknowledged by many as one of the most influential works by a post–World War II historian.

—WILLIAM C. PRATT, “HISTORIANS AND THE LOST WORLD OF KANSAS RADICALISM,” 2008

The Assistant fancies himself old school, still favoring the book-as-object that one can touch and smell, and in which one can underline and spill coffee. But in 2010 the writing, so to speak, is on the wall, and he wonders how long before he will capitulate and buy a goddamn e-reader. A menacing gloom overtakes the Assistant as he searches the stacks to find a copy of Hofstadter’s book, already missing these last precious days before everything is finally digitized.

The Populists looked backward with longing to the lost agrarian Eden, to the republican America of the early years of the nineteenth century in which there were few millionaires and, as they saw it, no beggars, when labor had excellent prospects and the farmer had abundance, when statesmen still responded to the will of the people and there was no such thing as the money power. What they meant—though they did not express themselves in such terms—was that they would like to restore the conditions prevailing before the development of industrialism and the commercialization of agriculture. . . . In Populist thought the farmer is not a speculating businessman, victimized by the risk economy of which he is a part, but rather a wounded yeoman, preyed upon by those who are alien to the life of folkish virtue.

—RICHARD HOFSTADTER, THE AGE OF REFORM, 1955

The Library of Googlexandria.

In the books that have been written about the Populist movement, only passing mention has been made of its significant provincialism; little has been said of its relations with nativism and nationalism; nothing has been said of its tincture of anti-Semitism.

—RICHARD HOFSTADTER, THE AGE OF REFORM, 1955

The Age of Reform serves up a pupu platter of vitriol and condescension that spurs the Assistant to write cheese dick in the margins of page 156. Hofstadter, the Assistant feels confident in asserting, is not only misguided in his analysis, but also kind of a jerk; however, he’s aware of a certain strain of Stockholm syndrome particular to academe in which the researcher comes to overly sympathize with the researched. He’s protective of his Populists as a mother hen now that they’ve kidnapped him from his own work, his responsibilities, his life.

Later in the afternoon, the Historian pops over to see if he wants to “powwow.”

“Sure, let’s powwow,” he answers. Now that she’s introduced the word, he can think of nothing but it. “I could use some more coffee. How about we powwow downstairs?”

“My treat.”

At Starbucks he orders his third venti dark roast of the day, and she a grande Americano and a cake pop. “Goddamn, I love these things,” she says as they take a seat. The quasi-fart smell of burnt coffee hovers over everything. “You’ll never believe what I saw two undergrads doing in the stacks.”

“I believe you,” he says, and she laughs before consuming the rest of her cake pop as though she were a sword-swallower. “So, what did you want to”—don’t say powwow—“talk about?”

She takes a swig from her drink, shaking her head.

“I don’t know,” she says. “It’s like I’ve hit a wall. I can’t figure out my argument, and the proposal is due the day after tomorrow.” She pauses a moment. “I don’t suppose you came across anything interesting.”

He tells her about coming across Hofstadter, and she says The Age of Reform was a seminal book and largely responsible for shaping public perception of the Populists as “ignorant, pitchfork-wielding rubes, screaming about silver. But refuting Hofstadter has driven the field for the last fifty years. I want to do something new.” She takes a sip of her drink and adds: “I need to do something new.”

“What do you mean?”

She grimaces, seeming to weigh whether she wants to answer, and finally says, “I have a two-book deal with the publisher.”

“Okay,” he says. “That’s great, right?”

“Not when the first book bombs.” She pauses. “Mine did.” This admission of failure feels like intimacy; he’s been admitted into her confidence. Suddenly he wants to tell her every dopey thing he’s ever done, every sin committed. “And the second book is contingent on a proposal, which I submitted last month, but they weren’t impressed. Not provocative. Too safe, they said. They gave me one more chance. That’s what’s due Monday.”

“What happens if they don’t like the new proposal?”

“They kill the book,” she says. She seems to recognize his silence as confusion and explains: “I’ve taken money for one book that did poorly and a second I couldn’t deliver.”

“So you’d have to give the money back?”

“Normally that would be the case.” She says this with a smile that is unsettling because she’s clearly upset. “Except I’ve spent it all.” The Assistant recalls a high school girlfriend who would double over in fits of laughter in moments of great despair or misfortune. “That’s how I bought my house.”

Neither of them says anything for a few moments.

“It’s not just the money, though,” she says. She looks at her Americano, slowly turning it in circles. “I’ve been here for a while, and I’m used to it, but with a successful book I could . . .” She doesn’t finish the sentence, but doesn’t need to. The Assistant realizes she is a woman who never once imagined she’d spend the majority of her life in Manhattan, Kansas, the Little Apple.

He wants to help, doesn’t like the idea of somebody murdering her book or fucking with her domicile situation, and tells her the ideas that came to him while researching, but she dismisses Organic Revolution and Grassroots vs. Corporate Roots with a look of squinting, silent disfavor. Later, when the library closes and they leave, she says they’re good attempts but just not right for this particular project. Across campus shine the bright lights of the football stadium. The cold night air does something strange to the oracular voice of the announcer so that only every fifth word is understandable.

“Well, what’re you up to?” she asks.

“I better check into the game. My teammates need me,” he says, nodding in the direction of the stadium. “You?”

“Home. I’m gonna work a while longer.” She starts to turn, but stops. “If you want, you could come over and we can work together. I’ll order a pizza or something . . . but you’re probably—”

“Thanks, but I’m pretty beat. I should—”

“Of course,” she says, “of course,” shaking her head, clearly regretful she extended the invitation.

“But I can help again tomorrow, if you’d like.”

“That would be great. I appreciate it.”

She says goodbye and leaves. For twenty seconds or so he simply watches her go, but then his feet begin to move in her direction, and ten minutes later the Assistant is standing on the opposite side of the street, watching as she lugs The Bag up her front porch, unlocks the door, and enters. The pretty yellow bungalow is just the kind of place he would have imagined her in. What am I doing? he thinks, as he crosses the street and stands behind a tall oak tree. She flips on lights and moves from room to room. Finally she seems to settle on the kitchen and the Assistant skulks over to some holly bushes on the side of the house. What am I doing? She uses a black wine key to open a bottle and pours a glass of what he suspects is Shiraz. This isn’t that weird. She invited me over, after all, so I came over. That’s all this is. The Historian sits at the small kitchen table, staring at her wineglass—thinking what?—and then suddenly begins to cry. Like really cry. Head down on the table, shoulders shaking. He’s pretty sure this qualifies as weeping. These do not seem like tears over only a failed book proposal; these are tears of existential worry. He’s seen something he shouldn’t have, which tends to happen when you spy on people, when you are engaged in activity of the pervert/voyeur/stalker variety. What the hell am I doing? He leaves quickly, cursing himself. I’m the worst. What was I thinking? Idiot!

“I’m so sorry,” the Assistant says the next morning when he finds the Historian waiting outside the library.

“For what?” she says, turning his way.

He looks at the tall building.

“For being late.”

“Don’t sweat it,” she says. “Place isn’t even open yet. Apparently on Sundays they don’t open till noon.” They both just stare at the library as though awed by its capricious sense of operating hours. “Buy you breakfast?”

They walk to a diner off campus and sit in a booth near the back. It’s not busy, the calm before the post-church storm. She’s wearing a Yo La Tengo shirt today and he wonders how long she’ll keep up the concert-tees-from-my-twenties theme. Today is the rare occasion she looks her age, whatever that is. She appears exhausted, proverbial bags under the eyes like she hasn’t slept, or like if she has slept she probably spent the time crying. Sleep-crying. Talk about a wet dream. He thinks of her last night, his shameful encroachment on her privacy. And yet, part of him is glad he saw what he did. To behold the suffering of others can be illuminating and strangely bond-forming. Perhaps that’s so because most of the time we don’t, can’t, or won’t, he realizes, apropos of his own strange relationship to his mother’s illness. He wants to tell the Historian about it, how sometimes at unexpected moments his body, too, will spontaneously combust in wet, lugubrious sorrow.

“I had a great night,” the Historian says.

“You did?”

“I think I figured it out. My angle for the proposal.”

“You did?”

“I did—thanks to you.”

She tells him how she’d all but given up on it when she thought back to their conversation earlier in the day and recalled something he’d said. For a brief moment he’s thrilled.

“You want to use Organic Revolution!” he interjects.

“Oh,” she says, “no. No, I don’t.”

“Grassroots vs. Corporate Roots?” he whimpers, which she refuses to dignify with a response.

“You brought up Hofstadter and The Age of Reform.”

“I did.”

“And I said refuting Hofstadter was old hat.”

“You did.”

“And that’s when I had the idea,” she says, her eyebrows raised, a slight opening of the mouth. “An apologia.” She says this uncertainly at first, as if only testing out how it sounds, but it’s just a matter of seconds before she avers, “I will defend Richard Hofstadter.” And like that, lured by the provocative potential of so-unfashionable-it’s-fashionable contrarianism, her hammer has forged an angle.

The Assistant, with the earnestness of his seven-year-old self: “But he was wrong.”

“Maybe,” she says. “Doesn’t really matter, though.”

“Doesn’t matter?”

“What matters is carving out space in the scholarly debate. There is no right, no ultimate position. There’s only interpretation.”

Interpretations are like assholes, the Assistant wants to say. Everyone’s got one.

“Besides, this is the kind of thing the publisher likes. Something controversial.”

“It does matter,” he says. “You can’t defend him.”

He feels both nervous and confident in eschewing his usual deference. In the hierarchy of their shared world, he’s supposed to know he is basically toilet paper stuck to her stiletto. Normally he does, but he can’t help himself. He’s gone into mother-hen mode. For a fleeting moment he imagines “Sockless Jerry,” William Peffer, and Mary Lease lying completely still in their graves, smiling. Equal rights for all, special privileges to none.

“Excuse me?”

But he also likes the Historian and wants to help her.

“I can do whatever I want,” she says, a slight your-move edge in her voice. Her eyes narrow a tad, as though if she really wanted to she could summon laser beams that would shred him into confetti.

“Of course you can,” the Assistant says.

For about half a second he felt like a hero, but then she iced over and readied ocular lasers, and now they fill the rest of their time with silent eating and occasional remarks that carry a we’re-still-cool-right? subtext. And they are still cool, it seems. Despite their fatigue, at least they have a goal. His mission is no longer to wander out into the world, writing down everything he sees. In the war room the Historian tells him to focus on compiling information on Hofstadter. She’s going to begin drafting the proposal. Before he leaves, she asks for his legal pads, the primary and secondary sources he’s taken notes on the past two days. “Oh right,” he says, removing them from his messenger bag and sliding them her way across the table.

The most influential book ever published on the history of twentieth-century America.

—ALAN BRINKLEY, HISTORIAN, ON HOFSTADTER’S THE AGE OF REFORM, 1985

Hofstadter’s ground-breaking work came in using social psychology concepts to explain political history. He explored subconscious motives such as social status anxiety, anti-intellectualism, irrational fear, and paranoia—as they propelled political discourse and action in politics.

—WIKIPEDIA ENTRY, 2010

There’s no question that Hofstadter’s writing was wonderful. But his understanding of the American past now seems narrow and flawed, and marked, inevitably, by the preoccupations of a generation that lived through Hitler and Stalin, by a gnawing anxiety that some kind of American fascism, a vicious right-wing movement coming out of the heartland, was not only possible but likely. . . . Hofstadter’s “status politics” thesis held that the Populists were driven to irrationality and paranoia by anxiety over their declining status in an America where rural life and its values were being supplanted by an urban industrial society. Populism, in this view, was a form of reactionary resistance to modernity. Here Hofstadter was the Jewish New York intellectual anxiously looking for traces of proto-fascism somewhere in middle America. He saw Joe McCarthy as a potential American Hitler and believed he had found the roots of American fascism among rural Protestants in the Midwest. It was history by analogy—but the analogy didn’t work.

—JON WIENER, “AMERICA, THROUGH A GLASS DARKLY,” 2006

I still think his position is as biased by his urban background and by the new conservatism as the work of older historians was biased by their rural background and traditional agrarian sympathies.

—MERLE CURTI, HOFSTADTER’S DISSERTATION ADVISOR AT COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY, 1955

The Assistant takes a break to get more coffee. He’s fading and there are still several hours to go. He should have just worn a beer helmet that holstered twin venti dark roasts this weekend. His research chapeau.

The Populists saw the principal source of injustice and economic suffering in rural America in what they called “the money power.” In Hofstadter’s analysis, this was evidence of irrational paranoia, of “psychic disturbances.” Moreover, Hofstadter argued that these denunciations of “the money power” were deeply anti-Semitic. . . . The problem with this analysis, aside from the paucity of evidence, was that anti-Semitic rhetoric was hardly a monopoly of rural Midwestern Protestants in post–Civil War America. The Protestant elites in East Coast cities were probably more anti-Semitic, and Irish Catholic immigrants in Eastern cities had no love for Jews either.

—JON WIENER, “AMERICA, THROUGH A GLASS DARKLY,” 2006

While Hofstadter’s misreading has a quality of grandeur, the source of his difficulty is not hard to locate: he managed to frame his interpretation of the intellectual content of Populism without recourse to a single reference to the planks of the Omaha Platform of the People’s Party or to any economic, political, or cultural experiences that led to the creation of those goals. Indeed, there is no indication in his text that he was aware of these experiences.

—LAWRENCE GOODWYN, The Populist Moment: A Short History of the Agrarian Revolt in America, 1978

This being Hofstadter’s most pointed-out flaw as a historian: an aversion to consulting the historical record.

In a liberal society the historian is free to try to dissociate myths from reality, but that same impulse to myth-making that moves his fellow man is also at work in him.

—RICHARD HOFSTADTER, 1956

The Assistant wakes under the gentle hand of the Historian. “Hey there,” she says. “You okay?” He’s fallen asleep on top of a picture of Hofstadter he printed out from the Internet. A bead of drool has dampened the paper and now dried, giving Hofstadter the impression of entirely elective plastic surgery gone awry. The Assistant nods, not quite verbal yet. He does not feel rested. It was the kind of nap that only makes you more tired. “Closing time,” she says. “Buy you a coffee on the way out?” It does not feel humanly possible to ingest more coffee than he has the last three days. He shakes his head and begins packing things up. He hands her the legal pad with today’s findings on Hofstadter. “Your notes have been very helpful. You found some great stuff,” she says. “I finished a draft of the proposal. It would be great to have another set of eyes on it, though. I wonder if you might look it over before I submit it to the publisher tomorrow morning. I’ll e-mail it to you tonight.” He tells her sure and they leave together. “I’m beat,” she says, yawning. “But it’s a good kind of tired”—speak for yourself—“like we earned it.” She thanks him for his help. “Obviously I couldn’t have done it without you.” She moves a centimeter toward him, which for a quick second feels like the beginnings of an embrace, but she stops and just pats him once, awkwardly, in the general vicinity of his shoulder. “Go get some rest, okay?” she says and turns to leave. Watching her go, he feels the slightest nostalgia for the godforsaken Bag.

Back at his apartment, the Assistant climbs into bed, intending only to redeem what he can of his truncated nap but wakes thirteen hours later. His body has performed some weird kind of intervention. Look, homie. We love you very much, but you’re not taking care of yourself so we’re unplugging you for a while. We’re doing this for your own good. He staggers over to his desk, which is a repurposed card table he bought at Walmart for twenty dollars when he started grad school two years ago. He checks his e-mail and finds seven from the Historian. The first of which arrived yesterday evening with the proposal attached, and they appeared steadily every few hours throughout the night and morning, sometimes with a new draft attached, sometimes with a thinly veiled entreaty disguised as a joke and full of exclamation points and ha-ha!s. It’s the e-mail trail of a crazy person; her body has not performed an intervention. The most recent e-mail from less than an hour ago, 6:27 a.m., said something to the effect that she needs to submit the proposal by 8:00 a.m. and could he pretty pretty pretty pretty please for the love of God read it ASAP! She would be soooooooooooooooooooooooo grateful!

Quickly he opens the attachment of the latest draft and reads. He’s disappointed when he remembers the core of her argument, which is really Hofstadter’s specious argument, denigrating the Populists. Maybe the book will become famous and he can perform a respectful takedown of it in a few years with his own work on the subject.

As he reads on to the second page, she makes the case for the importance of her book, its relevance to the field, and gives a synopsis, outlining the structure and timeline for the completion of the book. In the section titled “Research Plan,” she provides samples of the sort of evidence she hopes to incorporate into the project, and that’s when he sees some of his notes. He’s still a little groggy, but it’s strange. One note in particular seems off. “They are in fact reactionary betrayers of the term populist who want to carry forward a regressive agenda that will overwhelmingly harm the majority of the population.” Who the hell said that? It’s attributed in the proposal to William Allen White, the famous newspaperman from Emporia, Kansas, ardent Republican and fierce critic of the Populists. But he didn’t say that, did he? Then it hits him: White didn’t say it—the Assistant did. Or, rather, he wrote it. Friday night, when he was watching the news story on the Tea Party rally, he’d been scribbling on the pad and written down the thought, carrying on an imaginary argument with his dad, perhaps the germ that led him to Grassroots vs. Corporate Roots the following afternoon. He must have written it on his pad close enough to a William Allen White quote for her to have mistakenly attributed it to White. Surely she wouldn’t have knowingly done so. There are other quotes from his notes, correctly transcribed but taken out of context, and they’re presented in such a way as to move the Historian’s thesis a notch above conjecture. Your notes have been very helpful.

The Assistant had been an English major as an undergrad and recalls something he read long ago in a Brit-lit survey, Shelley’s A Defence of Poetry, in which the great Romantic argued that poets are the “unacknowledged legislators of the world.” If this is so, the Assistant realizes, then historians are the autocrats.

Next to the keyboard, the Assistant’s phone suddenly buzzes. For a moment he thinks the Historian has given up on e-mail and changed tactics, but it’s not her. It’s a text from Mom. Each morning she sends him a Bible verse for the day. The Assistant and God have been at an impasse since he was sixteen, and while he used to find these messages annoying, now he sort of looks forward to them. “Therefore, as God’s chosen people, holy and dearly loved, clothe yourselves with compassion, kindness, humility, gentleness and patience.” Colossians 3:12. Then a second text arrives: Missed u this weekend. May B nxt? Thinking uf u. Luv Mom.

The Assistant wants to be compassionate, kind, humble, gentle, and patient. He also wants to be honest and responsible. The clock on his phone, the only accurate clock in his apartment, says 7:31 a.m. He thinks of the Historian and her crumbling book deal, desperate to leave a place she doesn’t want to be, crying into her wine each night in her little yellow bungalow. Maybe the notes aren’t wrong after all. Maybe this is how history works. Maybe interpretations are like assholes. The clock: 7:33 a.m.

Sorry for the delay—totally crashed when I got home! he types in response to the Historian’s last e-mail. Just a couple of minor things. He points out a typo and a comma splice. I’m glad to have been of help, he types. Best of luck—fingers crossed!

He stares at the screen, the cursor blinking, and then he hits SEND.