2 .

FOLLOW THE HEAT —

BEGINNING, AGAIN

ONE OF MY favourite cartoons is by Australian cartoonist Michael Leunig. It shows a distressed man with wide-open, exhausted eyes, sitting in a doctor’s consulting room. He says, desperately,‘Doctor, I have a book inside me.’ The doctor reassures him that most people have a book in them and that he can refer him to a publisher. The man cries out that he just wants to be rid of it — to have it surgically removed, or dissolved with herbs, or some sort of therapy …

I understand completely this man’s distress — sometimes it would be easier if the urge to write could be treated as an illness. The urge keeps growing, won’t go away, but still it is difficult to know how or where to ‘cure’ it. You may not even have decided whether what you want to write is fiction or non-fiction — a short story, novel, or memoir. And what exactly is it going to be about? What shall you start with? And do you have enough material for it to be a book? Even if you are an experienced writer, finding the right genre, clarifying the subject and knowing where to start can seem daunting. Perhaps you have already started and you have come to a full stop. Given that you feel you have a book inside you — and given that you are not going to have surgery or try herbal remedies — what are the steps to take?

Clarifying your subject

What can a memoir be about? The short answer is: anything and everything. Here is a quick selection of memoirs from my bookshelf: Cecilia by Cecilia Inglis explores the experience of leaving a convent after thirty years as a nun; Holy Cow by Sarah Macdonald recounts a humorous search for truth in India; The Blue Jay’s Dance by Louise Erdrich is a meditation on nature written during the first year after her baby was born; A Thousand Days in Venice by Marlena de Blasi tells the story of love at first sight in Venice; Toast by Nigel Slater is a chef ’s childhood memories of food; and That Oceanic Feeling by Fiona Capp explores a mid-life return to surfing. There is really no limit to the possible contents of memoir.

Memoir can explore any experience of being human and can be shaped by any number of parameters or themes. It can be delineated by a time and place: Out of Africa, by Karen Blixen; a relationship: Velocity, by Mandy Sayer; an illness: Forever Today, by Deborah Wearing; social issues: Once in a House on Fire, by Andrea Ashworth; a journey: Desert Places by Robyn Davidson; or even an abstract idea: The Last One Who Remembers, my own first memoir. Whatever you have done, whatever has happened to you, whatever concerns you, is a fit subject for memoir. Write any list of things that have happened in your life and you will have created a list of topics.

Sometimes you may not have clarified your subject, or its parameters. Don’t let that stop you writing — if you wait until everything is clear and organised in your mind, you may never get started. Even without a properly defined subject, you can still start writing various memories and ideas that interest you. Your precise subject can emerge over time. The manuscript that became my second memoir, Whatever The Gods Do, began as notes on singing lessons I took one summer. Over a long period of time and many drafts, a memoir emerged about a friend who had died and my relationship to her young son. I had very little idea when I began what it would become, but the story itself seemed to know where it was going all along. It is important to learn to trust the gestation process that goes on underneath the conscious mind.

It doesn’t mean that you can sit watching television and eating chocolate every evening and the story will grow perfectly formed inside you! But neither does it mean you should allow a lack of clear direction or shape to prevent you from starting. You can help the gestation process in a number of ways. For example, you can clarify your topic by doing some ‘pre-writing’ — that is, start writing the thoughts floating around in your head. You are not writing the memoir, you are writing about it. This ‘pre-writing’ is a ramble, a kind of scaffolding, from which you explore the general territory. It can be very helpful in clarifying the material and the worth of your story.

‘Composting’ your material is also useful. Often, experience feels monolithic and can take time to break down into usable writing elements. Many times in writing classes, students tackle events which are too recent, and not only are they overwhelmed by the events emotionally, they also find their writing ‘lumpy’ and raw, much like the original materials of a compost heap. Time is partly the solution. Write immediate impressions certainly, straight after a birth or death or divorce or whatever you have experienced, but do not expect that this will necessarily be the final or truest word on the matter.

Experience needs to be filtered through the weathers of the self, remade by the processes of reflection, until it finds its richest form. You can help this process along by ‘digging’ over the memory, that is, writing about different aspects of it, testing out ways of approaching it, experimenting with starting in different places. I recently watched a documentary about the creation of ‘Imagine’, the song by John Lennon,and it was fascinating and reassuring to see such an accomplished artist try and then discard all sorts of possible arrangements until he came up with the song that is an anthem of hope even today. The process of creation is not a straight line but an experimental process with lots of trial and error. Feel free to make mistakes!

Many people also advise jotting down ideas as they come to you but, personally, I’ve found if I write something down, it is then out of my head and therefore not contributing to the general composting going on in there. It usually just stays in the notebook, not going anywhere. I find it better to have a session of jotting things down so that the thoughts are all on one page and thus can be re-read still in relationship to one another. That way, the composting process continues on the page. However, everyone’s method is different, so if the ‘jotting things down when they occur’ method works for you, keep it up.

It’s important in the beginning to ‘follow the heat’, as one of my writing teachers said many years ago. Rather than working out the sensible or logical place to start your writing, begin with the idea or event that you feel most passionate about. It is true that if you spend too much time trying to decide on the rational place to start, you can lose the impetus to begin at all. Commence with the event or person that excites your interest, arouses your emotion — positive or negative. It doesn’t mean you cannot change things around later, but begin with the heat, and follow the heat.

In relation to finding your subject, consider its length. Is it a short memoir, publishable in a magazine or collection, or is it book length? It is a key issue, for the wrong decision can result in too much material compressed, or too little material padded out — both common problems in manuscripts I have worked on. Sometimes, a subject which you thought might be a book turns out to be much more effective as a 5000 word memoir. Conversely, a short piece can keep growing as you find there is more and more under the surface and it can end up being a book length manuscript. A useful way to see if you have enough material for a book length memoir is to brainstorm your idea — see the first writing exercise later in this chapter.

Novel or memoir?

Should your story be a novel or a memoir? It might seem an obvious decision as a memoir relates stories about actual people and events, and a novel recounts imaginary people and events. But it is necessary to consider the issue because so many people have asked me whether they should write their life story ‘as a novel’. I always answer that one doesn’t write anything ‘as a novel’ — either it is a novel or it is not!

What I mean by this shorthand response is that a novel and a memoir are two different genres with different starting points and different literary requirements. A memoir must begin with and answer to the requirements of truthful exploration of an actual life; a novel must begin with and answer to the requirements of its own narrative structure. I believe that writing one’s life story ‘as a novel’ undermines the integrity of both genres.

To write a successful novel, one must be free of ‘what really happened’; one must let the needs of the characters and of the story dictate what unfolds. If you are writing your story ‘as a novel’, then you are lacking that essential freedom. Such novels often look and feel like thinly disguised autobiography, meaning that the ‘fictional’ characters and ‘fictional’ world of the novel are unconvincing.

The fresh engaging energy of an authentic voice is also most often lost when ‘a memoir as novel’ is attempted. In fact, this is the most crucial loss because the writing often becomes flat without the vitality of this personal voice. Most people writing in the first person, narrating their own life, have a voice that is at ease, confident. The change to the third person, and to the idea that this is a ‘novel’, often results in stiffness and a strained or contrived air.

I would not say that writing one’s own story as a novel never works,but I do suggest that it requires a certain amount of writing experience to make it work. The impulse to write your life is not a novelist’s impulse. Obviously, novelists ‘mine’ their own lives to write novels, but if your impulse is to write about your own life then, most often, that is what you ought to do.

It is clear that many people want to write their story ‘as a novel’ because their story is controversial in some way. There are family or friends who could be offended and distressed, individuals and institutions that may sue. It may simply be that they want their story told but wish to protect their own privacy. These are all valid reasons for fictionalising one’s story, but it is important to realise that one can also be recognised (and sued) when a story is written ‘as a novel’.

Look honestly at your story and its possible repercussions, and if it is important enough for you to write, then commit yourself to the truth as clearly as you perceive it. If you believe you cannot write what really happened but still want to explore the issues, then put aside the actual people and events, and consider writing a novel based on the essential issues or themes, or using a central narrative element of your own experience.

Leaping the hurdles to begin

Knowing you have that book inside you, knowing its general shape and size, how do you to start the process of putting it on the page? Everyone has different ways of starting, but in every case it involves leaping over several hurdles:

• Does anyone want to read about my mad mother/trip to India/life on an olive farm? Is it worth it? To jump over this one you must ask yourself not ‘Does anyone want to read it?’, but ‘Do I want to write it? Is it important to me that it is written?’ Once you are sure it is necessary for you to write it, then the hurdle of whether other people will want to read it falls to the ground.

On the other hand, practically speaking, it might be that there have been a number of other books written on the topic and perhaps readers have had enough of renovating houses in Italy or growing up in a zany, dysfunctional family. In that case you need to make sure that your perspective on it is fresh and original. If you want to write your Italian renovation memoir, then read recent publications on the same topic, perhaps look at your story again and see if there is something singular about yours that will make it a unique story.

• Do I have the right to tell the world about my mad mother/my boyfriend’s infidelity/my nasty neighbours? This is the trickiest question of all and one on which many memoirs founder. The anxiety induced by whether you have a right to tell the story can stop you in your tracks. This issue will be discussed in more detail in chapter 8, but in order to leap over at least the beginning hurdle,you need to ask yourself, once again:‘How important is this story to me?’ If it has been deeply significant in your life, then, as a starting point,you have the right to tell it as part of your story. You can also try the Scarlett O’Hara trick — worry about that tomorrow. Tell yourself that this is only a first draft — you can take the controversial topic out later if it will cause a problem. That way you can at least overcome the initial paralysis.

• Where in this huge tangle of events do I start? This question can delay beginning very effectively, especially when your memoir covers a number of years and/or very complicated events. It can sometimes be difficult to discern the actual origins of the story you want to tell. If this is the case, then try the patchwork quilter’s method — just start making small pieces. Don’t try to decide whether or not you are writing the beginning, simply start writing particular pieces, the incidents or memories that you keep thinking about. (Follow the heat!) This acts as a kind of warming up process — you don’t start running in the Olympic Games without having done a bit of training and you don’t start writing a book without doing a few warm-up exercises. These short pieces can be 300 words or 3000 words. It doesn’t matter. Doing short pieces will help you gain or restore confidence and you will have made a start without having to leap over the biggest hurdle at the beginning.

• I want to start but I just keep putting it off — how can I overcome the ‘one day I’ll do it’ syndrome? This endless delaying tactic usually comes from fear of failing: if you don’t start, then it is always a perfect idea, unmarked by messy struggle. ‘One day I am going to write a book’ is much easier to handle than actually starting and not succeeding. This is a particularly tricky hurdle and a cunning strategy is needed to overcome it. Instead of having a vague ‘one day I’ll start’, or a terrifying ‘today I will start’, give yourself a precise date in the near future — say, two or three weeks away — to commence. Make sure it’s a convenient date — not when you are at work or on Mother’s Day — write it on your calendar or in your diary, and then just keep it in mind. Work out which days of the week and times you can continue with the work. Pick a writing exercise from this book well beforehand. When the day comes, sit down and do the writing exercise. At first, only allow yourself half an hour for writing. Be strict; not a moment more. The combined strategies of a deliberately delayed start and a very limited writing time tend to lessen the anxiety and increase the desire and focus. Keep to the timed routine but after a few weeks give yourself an hour. Once you are well established in the writing, allow yourself as much time as possible.

• What if I have started, but can’t continue — how do I begin again? That feeling of having come to a full stop can be depressing. The writing just won’t go anywhere and you feel either uninspired, which is usually caused by over-planning, or utterly in a muddle, which is mostly caused by an early flaw in the structure.

If overplanning is the problem then you may need to throw the plan to the winds for a while and tack out in a different direction.Write something you had not thought of before. Try a topic which is off the beat or at a tangent to what you have been writing about. Try making a short list, for example, of ‘things that I am never going to include in this story’, then write a paragraph on each. It could open up a new window, let a fresh breeze into your manuscript. Sometimes all you need is to get other parts of your brain firing, other neural pathways functioning. Do something different. Take a class in Mongolian chanting, walk in the woods, ask someone from another culture about their childhood.

If a flaw in the structure is the problem, it is very probably because you have not been honest about what is important or about the real causes of events. That might sound accusing, but it is easy to avoid the real issues and it often results in paralysing confusion later on. The solution is not simple; it might mean dismantling what you have done and throwing out a lot of material, which is never an easy task. Take a break of a few weeks then write a paragraph or two clarifying what you were trying to do in the manuscript, then re-read it to see if you can spot where you left the rails. If you can’t see the problem, it can be useful to show it to someone else. A detached observer can often spot the gaping fault-line on which you have been trying to build. There will be more on troubleshooting structural problems in chapter 6,‘Finding Form’.

You will have observed that my preferred methods for dealing with hurdles are side-stepping them, or staring them down. Rather than backing away and giving up, or trying to leap over them and crashing down, it can often be best to either saunter around them — or to question whether they are really very substantial anyway and walk right over them.

READING

Are You Somebody?

by Nuala O’Faolain

When I was in my early thirties, and entering a bad period of my life, I was living in London on my own, working as a television producer with the BBC. The man who had absorbed me for ten years, and who I had been going to marry, had finally left. I came home one day to the flat in Islington and there was a note on the table saying ‘Back Tuesday.’ I knew he wouldn’t come back, and he didn’t. I didn’t really want him to. We were exhausted. But still, I didn’t know what to do. I used to sit in my chair every night and read and drink a lot of cheap white wine. I’d say ‘hello’ to the fridge when its motor turned itself on. One New Year’s Eve I wished the announcer on Radio Three ‘a Happy New Year to you, too.’ I was very depressed. I asked the doctor to send me to a psychiatrist.

The psychiatrist was in an office in a hospital.‘Well, now, let’s get your name right to begin with,’ he said cheerfully. ‘What is your name?’‘My name is … my name is …’ I could not say my name. I cried, as if from an ocean of tears, for the rest of the hour. My self was too sorrowful to speak. And I was in the wrong place, in England. My name was a burden to me.

Not that the psychiatrist saw it like that. I only went to him once more, but I did manage to get a bit out about my background and about the way I was living. Eventually he said something that lifted a corner of the fog of unconsciousness.‘You are going to great trouble,’ he said, ‘and flying in the face of the facts of your life, to recreate your mother’s life.’ Once he said this, I could see it was true. Mammy sat in her chair in a flat in Dublin and read and drank. Before she sat in the chair she was in bed. She might venture shakily down to the pub. Then she would totter home, and sit in her chair. Then she went to bed. She had had to work the treadmill of feeding and clothing and cleaning child after child for decades. Now all but one of the nine had gone. My father had moved him and her and that last one to a flat, and she sat there. She had the money he gave her (never enough to slake her anxieties). She had nothing to do, and there was nothing she wanted to do, except drink and read.

And there was I — half her age, not dependant on anyone, not tired or trapped, with an interesting well-paid job, with freedom and health and occasional good looks. Yet I was loyally creating her wasteland around myself.

One of the stories of my life has been the working out in it of her powerful and damaging example. In everything. Nothing matters except passion, she indicated. It was what mattered to her, and she more or less sustained a myth of passionate happiness for the first ten years of her marriage. She didn’t value any other kind of relationship. She wasn’t interested in friendship. If she had thoughts or ideas, she never mentioned them. She was more like a shy animal on the outskirts of human settlement than a person within it. She read all the time, not to feed reflection, but as part of her utter determination to avoid reflection.

As the title suggests, Nuala O’Faolain’s memoir is shaped around the question of identity and its relationship to parental influences. From the beginning, it is clear that she is jumping in the deep end, into the heart of the matter. It is a wonderful example of ‘following the heat’. As she says in her introduction, ‘…eventually, when I was presented with an opportunity to speak about myself, I grasped at it. “I’m on my own anyway,” I thought. “What have I to lose?” But I needed to speak, too. I needed to howl.’ Like the howl of many artists before her, like the yawp of Walt Whitman and the scream of Edvard Munch, her howl resounded in many other hearts.

WRITING EXERCISES

1. Brainstorm circles

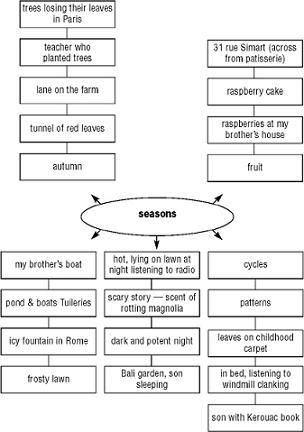

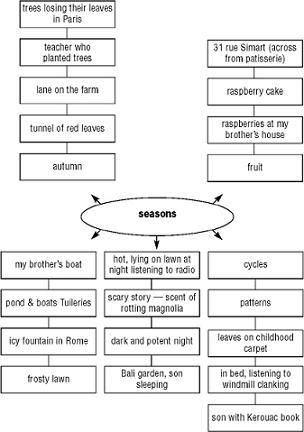

This is a way of seeing how much material you have stored away in your mind on a particular topic. Start by drawing a circle and writing in it the subject you think you want to write about. It can be a word or a phrase, for example, ‘Seasons’ or ‘Iraq 2003’ or ‘Michael and Cancer’ or ‘Mountain Climbing in Peru’. Then you write the first association that comes to mind, then the association that comes to mind from that one, and so on. You free-associate from the previous word, not back to the central word or phrase. When you have reached the edge of the paper or come to a stop, go back to the central word and start another line of association. Do this five to ten times — see the diagram opposite where I have free-associated from the word ‘seasons’.They are my personal associations and so are very idiosyncratic. You will end up with a spider’s web of interconnecting associations around your central idea or image. It will give you an indication of how rich — or not — your idea is, and it will give you a list of possible pieces to write. (20 minutes)

FOLLOW THE HEAT

2. Ramble

This is useful if you are unclear about your subject matter or when you have, perhaps, just a vague idea. Start with a very uncertain phrase, that is, expressing how vague you feel, and head off with no clear direction in mind but a willingness to explore possibilities. For example, you might begin: I feel I might want to explore that year I spent in London — I don’t really know why. It’s just that the image of that bare little room with the slatted bed keeps coming to mind. There was one picture on the wall, though, a poster of a mountain in Italy. Maybe that’s why I went to Italy the following year. Perhaps that is what I want to write about — the little things which have changed my life … And then you keep on rambling! This exercise is meant to be very loose, very discursive — a way of loosening the order of the organising brain. Follow any train of thought that arises as you wander. It is not meant to yield good writing, but to find the trail. It is like sifting through the contents of a large drawer, not looking for anything in particular, but alert to treasures that may be uncovered. (20 minutes)

3. Locking editors in the closet

This is for writers who feel paralysed or blocked by a person or persons who might disapprove of the memoir. You simply name all the people who might be upset, disapproving or in any way limiting to your writing, and mentally lock them away in a cupboard in your mind — or send them to a tropical island if you wish — somewhere where they are not going to see what you are writing. Then start with the phrase, It is very difficult for me to write about — and continue. It is interesting how naming the problem you are having will often lessen its hold over you, at least enough to get started. (20 minutes)

4. Patchworking

This exercise is also useful for writers who know the general territory they want to write about, for example, ‘Travelling Alone in South America’, but do not have a clear idea of the story or thematic thread, or even if there is one. Write a short list of particular memories of the time — running into an old school friend in an Aztec ruin, getting lost in Buenos Aires, the sounds of the jungle — and start writing the pieces, one by one. Do not worry about the overall shape; simply make each piece as if you were making the pieces of a patchwork quilt. When you have written a few, then you can start looking at how they might be placed together, but to begin with, just concentrate on making the pieces. (1 hour)

5.Three beginnings

If you are clear on the subject of your memoir already, deliberately write three different beginnings from three different times in the story. Don’t try to decide beforehand which one is the best place to start, just pick three intriguing places. Give each your full attention — as if this is ‘the one’. After you have written them, see which one is the best. (20 minutes on each)