Lesson 5 – Entering and Manipulating Data (and the basic rules of good spreadsheet design)

In the last few lessons you learned the ins-and-outs of the Excel Ribbon interface and all of the commands that the Ribbon puts at your fingertips. In this lesson we’ll start exploring how to actually use them by setting up some business scenarios, entering and editing data, preparing them (a workbook) for distribution with formatting, and finally preparing it for printing.

Next to using functions to analyze your data, the actual data input is one of the most important aspects of using Excel. After all, without the data, you have nothing to analyze. In a small business scenario you might not have a large database or mainframe system to input your daily transactions, but instead rely on manual methods or some type of small business accounting software, like QuickBooks. A lot of times that information is great, but what if it doesn’t adequately measure those aspects of your business that will help you manage it smarter, like customer turnover vs. retention rate, or employee sales performance? Small business accounting systems are great for telling you where you stand financially, but they don’t often give you the deeper insight that can really help. While there are certainly merits to making decisions based on your gut instinct, when you have a tool like Excel right at your fingertips you should use it. The same can be said for managing household finances; why do by hand what you can have Excel do for you? Regardless of the need, it all boils down to how to you get your information from its source to Excel, and once it gets there what do you do with it.

In this lesson we’re going to talk about how to enter and edit data, how to manipulate it once it’s there, how to format it so it looks the way that you want, and finally prepare it for printing/distribution. In this lesson you’ll work with a companion workbook that is laid out in steps to help you understand the process.

Before you just start putting your information/data into a worksheet, you need to understand some fundamental concepts behind good spreadsheet design (these concepts go beyond just Excel as well). This course is laid out in such a fashion as to reinforce those steps, but we’ll go over them here and explain them in detail.

- • Questions - Before you start to enter any data in a worksheet, you should ask yourself some questions, because the biggest part of the design and question phase is to determine your function and audience.

- • Is there another tool that could do this more efficiently?

- • Is this necessary? (e.g. do I really need to create a shopping list in Excel when a pen and paper will work fine?)

- • What do I want to keep track of in here?

- • What do I want to measure (both broadly and specifically)?

- • Who is my audience/user(s), will it require data input, and if so from whom?

- • What is my primary data source? Will I be pulling data from a company server or the Internet, will users manually input data, or a bit of both?

- • Will this be an analytical tool (something that you might use for business planning), is this a flashy daily sales leaderboard you want to post to pump up your team, is it something like an employee schedule or calendar that you’ll just post on a wall and let people fill in by hand, or is it more of a data warehouse, like a customer list? All of those require some degree of data input, but the extent and methods are up to you.

Good planning goes a long way - there is nothing worse than expecting people to use a poorly designed spreadsheet; if you make it difficult for people to enter data, they will make it difficult for you to get it back.

If you can answer those questions to your satisfaction, then move on to Step 1.

1. Planning

a. This is where you conceptualize your overall design. If it’s something simple that you’re not going to reuse, then just go ahead and whip something together it, but if this is going to be something sustainable, like a pricing matrix for your products, then you’ll be better off putting some time and effort into design before you start tapping away on the keyboard. This may sound counter-intuitive, but most often the best spreadsheets and databases are laid out on paper before you even turn on the computer. If you can sketch out an overall idea of what you want, then it will be easier to set up something that can be flexible and grow with you. It doesn’t have to be perfect, just a bit of a road map to get you going; but you certainly don’t have to do it and many great spreadsheets have been built without it. However, there’s nothing worse than being stuck with, or having to redesign a poorly built spreadsheet that has consumed a lot of hours building, especially when it can all be avoided up front.

b. Inalienable Design Rules

- • Rows vs. Columns – Your detail data should go across, not down! This concept borrows from intelligent database design, which was probably derived from the old accounting ledgers that led to the spreadsheet in the first place. This is commonly referred to as a “flat file format”. If you can just keep this single, simple precept in mind anytime you start a new spreadsheet then you’ll be in pretty good shape right off the bat.

- • Following is an extreme example of data gone “bad”, next to the way data should be laid out. Can you guess which one is better?

Figure 215

- • If you haven’t already guessed, the example on the left is the “bad” one. That data is largely unusable because there’s just no way to discern one record from the next. How do you know when one record ends and another one starts? You might say that you could key on the numeric address like “123 Main Street”, but what if the address doesn’t lead with a number, like “Evergreen Terrace #3”? Another issue is that there’s no normality, because the first two customer records don’t have zip codes, but the third does. This means you can’t standardize any process like Mail Merging without a large degree of failure. Another thing to think about is that even with over a million rows in Excel 2010, you might see how you could quickly run out of room by going down (exponentially), whereas you could technically* add a million+ customer records if you formatted your layout correctly (across vs. down). (*Technically – if you have a million+ customer records you need to be dealing with a database, like Access, not Excel! Just because you can store large quantities of data in Excel it should not be mistaken for a database application, which it is not. It is an analysis tool).

c. Data Separation – Wherever possible separate your data as much as possible. For instance, storing “Bob Smith” in a single cell is much less usable than having separate columns for First Name/Last Name. Both can be parsed out (split apart) with functions, or with Excel’s Data, Text to Columns tool (we’ll discuss both later), but it’s often unwieldy at best and should be avoided if at all possible. This becomes really important when you start dealing with middle name/initial, suffixes/prefixes, etc. To borrow a math term, the more you can break your data down into its lowest common denominators the better. Just think of all the Internet sites where you enter First Name, Last Name, Address, City, State, etc., separately. Those are all database driven, and they follow those rules for a reason.

d. Another thing that can chuck your data right out the window is to store it all in a single cell:

Figure 216

- • In the “Really Bad Data” example the data has been crammed into one cell, which renders it all but useless. No degree of formulas or VBA code can reliably strip that data out, so you might as well start over. Unfortunately, data like this is all too common in Excel, so this is a more than gentle hint to not let this type of data into your world.

- • Try not to think 2-Dimensionally – Excel is just like a ream of paper in that it’s a series of worksheets stacked on top of each other, but that doesn’t mean that you can’t develop relationships between one worksheet and another (or other workbooks for that matter). One of Excel’s strongest points (thanks to its powerful functions) is the ability to store data on different worksheets and relate them via a common identifier (much like a database). For example, you can have table of employees with all of their information (Employee #, Name, Address, Wage, Hire Date, etc.) on one sheet, and then a transaction list of sales by employee number. A few simple functions will let you summarize sales by employee #, yet you can have the information remain on separate worksheets (in the case of sensitive employee or customer information, those worksheets can be hidden from your users). Grasping this can be a big hurdle for a lot of people, because it just seems so far-fetched, but it’s really very easy, so keep that in mind when you’re planning your workbook.

2. Design & Build

a. Once you’ve decided on a function for your spreadsheet(s) you need to focus on a design, then it’s time to start building the spreadsheet. You should already have an overall concept in mind, like if this will be a balance sheet with expense categories in rows on the left and months as your column headers, or an employee schedule with employee names in rows, and days of the week as column headers. As you gain experience with building spreadsheets for different scenarios you’ll find yourself reusing your favorites over and over again. The initial pain is in setting up the first few, but once you get a few under your belt you’ll quickly know how to start a new one with relative ease.

b. The next step is to build the guts of your spreadsheet by defining the row and column headers that you want (e.g. Employee 1, 2, 3 & January, February, March, etc.). You’re still very flexible at this point, so don’t get too bound by the idea that you can’t change your mind.

c. Try to keep things as simple as possible. An overly complex model can be confusing and difficult for users to understand. A spreadsheet can be very powerful thing even with a simple, time-tested design.

d. Try to reuse elements wherever possible. Why type in January-December for each row, when you can do it once and refer to the original values throughout the worksheet, and even the entire workbook?

3. Populate – Sample Data

a. Once you’ve gotten your design down (or relatively close) it’s time to start entering in some sample data. At this point there’s no reason to enter in real data unless it just happens to be right there in front of you, otherwise just make up some numbers that will reasonably represent what you plan on entering later. All you’re going to do here is set the stage to evaluate your functionality. You don’t want to invest a lot of data entry resources at this point just in case you decide to completely change your design.

4. Evaluate/Calculate

a. This is where you start putting Excel’s true power as an analytical tool to use. Here you start developing the formulas that you’ll use to summarize and evaluate your data, be it simple sums or averages, or complex ratios and relational formulas.

b. We’ve got a whole lesson that will be devoted to using Excel’s functions, so this won’t cover much, but you should try some of the AutoSum features that we discussed earlier and see how they work in a real situation. As we get into the Function lesson, some more insight about what you can do in Excel will also help expand your design capabilities. One of the limiting factors when people design spreadsheets is that they just don’t know that something is possible, so they don’t think to add it. You’ll instantly know when you have one of those “Ahh haa! I didn’t know Excel could do that!” moments.

5. Format

a. As much as you might be tempted to add formatting elements while you’re building your spreadsheet, you should try to avoid it and wait until it’s functional. Otherwise you will find yourself going back and adjusting the formatting as you adjust your sheet design. This also holds true for other applications, like Word or Power Point; saving the formatting for last will save you time in the long run. You can easily get bogged down investing time into formatting a sheet, just to throw the design away and start over, like crumpling up a piece of paper. It’s a shame to have formatting time wasted like that. Fortunately, formatting is easier than ever with Excel’s new styles & gallery selections, as well as themes. What used to take a lot of manual labor can now be created in just a few mouse clicks.

6. Populate – Live Data

a. Now that your workbook/sheet is set up and doing what you want, it’s time to start putting real data into the workbook. If you’re entering the data yourself or pulling it from an external source you generally don’t need to worry about protecting the workbook/worksheets. But if you’re going to be relying on users to enter your data, then you’re strongly encouraged to take advantage of Excel’s protection, so they can’t inadvertently overwrite your functions. As mentioned earlier, you just select the cells/ranges in which you want to allow data entry, goto Format, Cells (Ctrl+1), Protection and uncheck “Locked”. Then protect the worksheet from the Review tab, selecting the particular elements that you want to allow.

7. Report

a. Now that your workbook is set up and functioning what do you do with it? The final output should have been something you considered in the design phase when you detailed the workbook’s functionality and your audience. This is where you start telling a story with your data, and all data can tell a story, it just depends on which story you want to tell and how. There is no right or wrong way to do this, it’s largely a matter of preference. Some people prefer to let the numbers speak for themselves, others like to tell a story visually with Charts and other visual aids, while others want to add in end-user functionality with Pivot Tables. This is another area where you’ll get some good ideas by browsing through the Microsoft Template Gallery.

8. Distribute & Collaborating

a. The last step is distribution. Again, your audience and the data use dictates how you’re going to send the information out. The first thing you do is hide any worksheets that contain sensitive personal or customer information. If you hide worksheets you’ll also want to protect the Workbook, not just worksheets in order to prevent the hidden worksheets from being unhidden.

b. If your workbook is for data entry, you’d need to take steps to protect sensitive cells or those with functions from being overwritten.

c. If the workbook is purely for review purposes, you might want to consider creating a copy of the workbook, then on each worksheet, select all cells (Ctrl+A), Copy, Paste Special, Values. This will get rid of all your formulas, and it will also serve to shrink your workbook’s size. Another option is to save as a PDF. If you don’t have a PDF writer, you can find several on the Internet for free, and Office 2010 now supports creating PDF’s natively (File, Save & Send). PDF’s are also a good way to secure your data. If you send out an Excel workbook, even as values only, the data can still be copied, which you might not want.

d. For workbooks, and just about anything else where you need user input, in the past most people generally just e-mailed them back and forth, but the advent of online file sharing services have rendered this all but obsolete. Take a look at Microsoft’s SkyDrive service, which will let you post files in a secure cloud-based environment. You can invite people to share documents with you, and set what degree of changes they can make. And Microsoft has released its new Office Web Apps, which let you work in a workbook real-time with other users with a great new feature called “Co-Authoring”. If you have users spread out in different locations this is a great way to move documents back and forth without relying on e-mail and wondering which version of a workbook is the latest, who made changes to what and where. And best of all it’s free, so there’s no reason not to at least give it a try.

Entering and Editing Data

- • Now that you’ve laid out your plans with regards to function and design, it’s time to start developing your workbook (many people refer to this as building a model, so if you hear someone saying something like: “we calculate our pricing using a complex model”, they’re most likely referring to a spreadsheet). The example you’ll be following in the companion workbook is a company Monthly Cash Flow statement by week. While we’re only going to build one worksheet in this example, in reality you would probably have 13 worksheets, one for each month and a summary at the end (when we get to the Function lesson we’ll discuss how you can quickly summarize the data from those 12 monthly worksheets).

- • The first step is to determine your primary categories, in this case Cash Received, Cash Disbursed and Final Cash Position, or balance. Note that a lot of people will put their category headers in ALL CAPS as a way of making them stand out. You could also BOLD them and format the header row, it’s entirely up to you.

- • Next since we know we’re going to do this on a daily basis your dates will go across your columns. In this case just enter the first week of the month in column B (mm/dd), then to fill the rest of the dates you can use the formula “=B1+7”, and copy that across instead of manually entering the dates, or drag the fill handle from the first cell across to the last and let AutoFill do it. (=B1+7 simply adds seven days to the original date and will repeat each time you paste it, adding seven days to the previous entry, and so on). Now that you have Rows & Columns defined, you need to break down the line items for each primary category, and then determine where you want to have sub-totals. If you don’t already have expense categories for your business, you can find plenty of examples in the Microsoft Template Gallery. Fortunately, Cash Flow categories are relatively standard, so you probably won’t need to make a lot of modifications to whatever list you find. In the companion workbook there are only 22 sub-items for Expenses. The nice thing about building models is that once you have the base model done, you can reuse it any time you want and not worry about having to re-enter all of that information.

- • Lastly is how do you want to summarize your data? Certainly you need to sub-total each primary category (Cash In, Cash Out & Final Balance), but you might also want to summarize other details, like all payroll elements (exempt vs. non-exempt wages, commissions, etc.) as separate line item sub-totals beneath the statement. In some cases if you have more than one primary revenue stream, or multiple locations, you might also want to break down your cash receipts by those elements. Now is the time to add details, because as your model progresses it becomes more of a chore to add new elements, as well as keeping track of everything you need to update those additions throughout your workbook. Think about what it might take to add a single line item to your 13 Monthly worksheets, as opposed to doing it while you’re still building the first one. (Although we are going to talk about how to make the same change(s) to multiple sheets shortly). In the Cash Flow example there are several line items of operating information

Entering and Editing Formulas/Functions

- • So now you have your worksheet designed and all of the basic elements in place, but at this point it’s nothing more than a shell, so you’ll probably want to put some sample data in there so you can start building your formulas. Adding sample data to a model while you’re building it can generally save you time vs. entering in your own information, because you can let a single repeated function do it for you, rather than manually entering a series of sample data. All you want to do is test the functionality of the formulas that analyze your data, you’re not actually analyzing your own data at this point, so there’s no point in representing until the model is built.

Figure 217

- • A fast and efficient way to enter a lot of data is to use a function that will generate random numbers for you, so select the range that you want to fill, then in the first cell enter =RAND()*100, but don’t hit ENTER. In this case you want to confirm the function with CTRL+ENTER, and you’ll instantly have something like the following example. If you hadn’t guessed, CTRL+ENTER will fill an entire range with the active cell’s value, function or formula.

Figure 218

- • Not very pretty is it? Before you move off of this selection, enter CTRL+SHIFT+4, which will instantly format that range as Currency (CTRL+SHIFT+1 = General Number format, CTRL+SHIFT+4 = Percentage).

- • Now you can select B2:F2 and copy and paste it to the other rows in the Purchases section. Remember, the shortcut for copy is CTRL+C, while paste is CTRL+V. Here’s another trick for quickly entering copied data across a large range: once you’ve copied B2:F2, go down to the beginning of the Purchases section and in the first cell hold the SHIFT key, then arrow down to the bottom of the range. Once you get to the bottom enter CTRL+V and the formulas will be pasted to the entire range. Note that you didn’t need to select the entire range, just column B – Excel knows that you want to copy it across to column F.

Figure 219

- • By now you’ve probably noticed that when you paste your sample data keeps changing doesn’t it? That’s because the RAND function is a particular class of function called Volatile, which means that any event that takes place on the worksheet that causes calculation (like entering a value in a cell) will cause volatile functions to recalculate as well. If you want to stop that behavior you can either turn off Calculation in File, Options (you can manually recalculate at any time with F9), or, since you have your sample data in place, you can copy each range, then paste as values to remove the formulas (keyboard shortcut: CTRL+C, ALT+E+S+V).

- • Now it’s time to start summarizing some of that data, so go back to column B to the total row for Cash Receipts. Now from the Formula tab click on the AutoSum button and choose SUM. Excel will input the formula for you, but it will also give you a chance to evaluate it and see if it’s gotten the range correct. If you agree with Excel’s decision, then just hit ENTER. Then Copy & Paste cell B5 to C5:F5, by Copying and holding down the SHIFT+RIGHT ARROW key to select the range, then CTRL+V to paste. Note that you didn’t need to move off of cell B5 in order to paste, Excel just replaces the existing function with the same thing. If the source cell and the destination range are contiguous, it’s generally faster to copy the source cell and keep it as part of the destination range, than it is to move off of it. You can go ahead and repeat the AutoSum for your Expense category, then it will be time to calculate the difference (often referred to as Variance) between Cash Receipts and Expenses.

- • This next exercise is a simple one, and it’s not so much about learning a particular formula per se, but the steps to enter it. Go to the Cash Position row (B31) and enter “=” (this lets Excel know that you’re entering a formula – if you’re entering text you just start typing as you’ve seen). Next click on the Total Cash Receipts row (B5) and enter a minus sign (either from the primary keyboard, or the 10-Key pad). By now you’ll see “=B5-“ in the formula bar. Now click on the Total Cash Paid out row and hit ENTER. Excel will automatically return the difference between Cash In/Cash Out. You didn’t need to use the mouse-click method In order to select the formula’s cell references, you could have also used the keyboard navigation keys. In fact, just for practice, pick any empty cell, enter “=” and just start moving around with the arrow keys and watch the formula as you do. See what happens if you enter any operator (+, -, /, *) and move to another cell. Each subsequent action locks the previous action into the formula, so entering the minus sign in your variance formula locked B5 in the formula. And you don’t always have to use mathematical operators; for instance this formula will sum cells in a non-contiguous range: =SUM(B10,C13,D20,E24,F28). To enter that function, you would type “=sum(“ then click on the first cell in the range and lock it in place by entering a comma, and repeat until you have your entire range selected and hit ENTER to confirm it (you can actually do it really quickly if you enter the comma with your left hand, and click the cells with the mouse in your right, or vice versa if you’re a lefty). Note that you don’t need to capitalize the function name (Excel is blind to cases and will convert it for you), nor do you need to enter the final parenthesis to close the formula, Excel will do that for you as well.

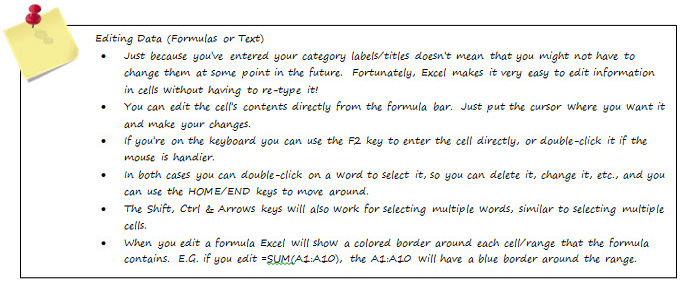

Figure 220

- • Now that you’ve entered a few formulas you need to know how to edit them if you need to make changes. If you know a formula is just plain wrong and you want to use something else it’s generally just as fast to start over by simply typing right over it. As soon as you start typing, the previous values will be wiped out, although you can retrieve them by hitting ESC before confirming the new formula. If you’ve already confirmed it, then CTRL+Z will restore your original. Editing formulas is

- • At this point you have your Row & Column headers defined, you’ve got your sample data in and checked that your vertical formulas are working, but what about horizontal totals? Right, you need to add those as well, so goto cell G1 and enter Total. Then in G2 you can invoke the AutoSum tool from the Formula bar, enter your horizontal total and copy it to the other relevant rows. Notice how the AutoSum knew to go across this time instead of up. If you don’t confuse it with too much data then AutoSum will usually do a pretty good job. But you’ll always want to check the blue formula border and make sure it got everything/not too much.

Copying Formulas - Absolute & Relative References

- • So far you’ve entered some formulas, and copied/pasted them to other cells. The next concept, Absolute & Relative Referencing, is absolutely essential to know when you start working with formulas and getting them to evaluate the range/ranges that you want and expect.

- • One basic precept of spreadsheet design is to make it as simple and efficient as possible. In the current Cash Flow example, the dates in C1:F1 consist of a formula that refers back to cell B1, where you would initially enter the starting date. Then B1:B7 was copied to the other date header rows. This isn’t very efficient as each row of dates is dependent on the value in column B of that row, so if you wanted to change the starting date you’d need to do it in 3 places (in this example, think about how many potential changes you could make it a really big model!) We’re going to change all of that and make all of the dates dependent on a single cell, B1. So go back to the Cash Flow example, cell B7, and enter =B1. Now copy that across from B7 to F7. Next copy B7 to the next date header row in B33:F33. You don’t get quite the result you expected did you? You got something like this right?

Figure 221

- • What are those nonsensical dates you’re probably asking. Before you think that Excel’s broken, you should understand that Excel did exactly what it was told to do! Take a look at the formula in B33. It’s =B27 right? When you copied the formula in cell C7, and moved down to B33 you moved down, or offset, 26 rows. So if the original formula in B7 was =B1, and 1 + 26 = 27, then B1 + 26 =B27. Well that’s kind of stupid isn’t it? Not really, because there are times you want your formulas to change like that. That’s called Relative Referencing. It means that the formula is going to update relative to its position on the worksheet, not necessarily the cell to which the formula first referred. In our case we wanted to always be referring to B1 right? Yes and no; we want to refer to B1 as we copy the dates down, but what about when they’re copied across? If you always referred to B1, then your Cash Flow statement would only have one date, so we really want B to change to C to change to D, and so on as it gets copied across. To do that we need to mix Relative and Absolute Referencing, which you would do with =B$1. The $ is the key to Absolute Referencing, as it fixes whatever it’s attached to in place. So in this case the B will change as it’s copied across, but the 1 will always remain a 1 as it’s copied down. You’ll see more examples of this as we get into the Functions & Formulas lesson.

- • A quick way to update Absolute/Relative References is to enter Edit mode on that cell, then select the range reference you want to change and hit the F4 key. Each time you hit F4 you’ll toggle between another reference state, $B1, $B$1, B$1, etc. In big formulas this can be faster than trying to add the $ by hand. Once you have the formula edited you can recopy it and this time the dates will correctly reference the master date.

- • If you just want to move formulas around, you can use the Cut & Paste option (CTRL+X, CTRL+V) to move formulas from one location to the next without modifying any formulas.

Lists & AutoFill

Figure 222

- • These are two tools that often work in conjunction and can save you untold amounts of time in the course of a year (if you remember to use them). Unfortunately, these are features that are often overlooked by even seasoned users. As you may remember from the introductory lessons, Excel maintains a set of internal standard lists for Days and Months, and dates (although they are calculated vs. stored in a list). You can use those lists anywhere in your workbooks. Let’s say you were building a Summary worksheet for your 12 monthly Cash Flow statements. You’d have January-December as the column headers in the summary. The logical assumption for populating those dates in the workbook would be to manually enter them, and you’re partially correct, but you only need to enter one moth and let the AutoFill tool do the rest for you. In the Lists & AutoFIll worksheet example you’ll see January entered in A2. Select A2 and in the lower right-hand corner, grab the Fill Handle (when you hover over it your cursor will turn into a dark cross), and drag it down. Watch the Control Tip Text as you drag it down, and you’ll see each subsequent month as you drag. When you release the fill handle those months will be filled in for you. That’s so much faster than continually entering months by hand. In the next example you’ll see Month-Year entered, so try dragging that one down and see what happens. (If you hold down the CTRL key while dragging you’ll just copy the original value, not increment it). Next look at the date, drag that down and see what it does. Before you go do anything else though, you’re going to see one of the neat things that AutoFill can do with dates. Right-click on the AutoFill Options button at the bottom right-hand of the range you just filled and you’ll see the following sub-menu. That’s right, Excel can fill just certain incremental date elements for you. One of the most common is the ability to fill weekdays only.

Figure 223

- • Another handy tool that was discussed earlier is the ability to fill a series without having to use the AutoFill handle and drag it across or down, which is great for an extended series. For instance, let’s say you were building a pricing model and you wanted to see what would happen at certain volume levels, but you don’t want to enter them all in by hand. In cell E5 on the AutoFill worksheet, goto Home, Fill, Series and you’ll see an expanded Fill dialog. In this case enter 250 for the Step value, and 50000 for the Stop value. When you click OK, you’ll see that the 15000 entry in E5 has incremented by 250 all the way to the right until it hit 50,000.

- • The List feature is one of the things that drives AutoFill, but it doesn’t have to be limited to Microsoft’s values, you can enter your own. Here’s an all too common scenario: a company has a dedicated workbook that has a lot of relatively static company information, like Operating Units (Sales, Production, Accounting), Regions (East, West, North, South), Offices (New York, Dallas, Los Angeles), even their list of Cash Flow or General Ledger Accounts, and so on. Whenever a new workbook is created that needs one of those lists, someone opens up that other workbook, copies the list in question, returns to the new workbook and pastes it in, then goes back and closes the list workbook, or worse they copy more data. That’s actually quite a few steps when you could just do it with AutoFill. The key is to build your lists into Excel, which is equally easy. On the Lists & AutoFill worksheet in the companion workbook you’ll see a list of countries beginning in A20. Go ahead and select that range, then goto File, Options, Advanced, Edit Custom Lists (it’s near the bottom), and you’ll get the following dialog.

Figure 224

- • Notice how Excel has already recognized your selection as the list range it’s supposed to import. When you click Import you’ll see your list beneath the existing Microsoft lists, and in the currently selected list box on the right.

- • That’s all well and good right, but what good does it do you? Well, anytime you need to populate that list in any workbook, all you need to do is enter a beginning value (it can be any value in the list), then drag the AutoFill handle down and Excel will build that list as far as you want it. It’s a lot faster than copying and pasting from another workbook.

Data Validation

- • This is a tool that goes hand-in-hand with lists. Data Validation allows you to use a list to limit cells to only accept values that fit parameters that you specify. This is great for ensuring that users follow your rules regarding what they can and can’t enter. Some examples would be limiting an Employee Annual Wage Increase to 5%, or limiting the date range in a Time-Off Request to certain periods. Data Validation can also use your list values to give the user a drop-down list of selections that they can make, and not accept anything not in the list. This is a great tool to prevent errors, because when you provide users with a list they can select from, then they don’t have to type (and possibly misspell) the input value. It can also be great for things like order forms where you might have detailed product names, and don’t want users to have to re-type them for each order. Data Validation can be found on the Data tab. You can recognize a cell with Data Validation because it will display a drop-down symbol on the right-hand side of the cell when you activate the cell.

Figure 225

- • First we’ll look at setting up Data Validation to only accept certain values. Select any cell on a blank worksheet and invoke the Data Validation dialog. For this example we’ll limit the value entered to only dates greater than today’s date (using your system date), so select Date from the list of choices. As soon as you do you’ll see the Validation dialog change a little bit so its Date options are exposed. In the Start date field enter =TODAY(), then OK. Now try to enter a date before today’s in that cell, and you’ll get a not-so-subtle error message.

Figure 226

- • Fortunately, you can modify the error message to be much more palatable to your users.

- • In the Data Validation dialog there were two other tabs behind the primary Settings tab (Input Message and Error Alert). The first lets you define your message while the second lets you identify which kind of errors you want to allow (if any).

- • The Input Message will be seen when a user enters the Data Validation cell, while the error message will appear when an invalid entry is detected. You can disable error checking and allow user entries by unchecking the “Show error alert…” check box

Figure 227

- • Data Validation List selections don’t have the same degree of flexibility as the input options, but you get to define the selection list, so you pre-determine what can be selected. For this example enter several city names in a blank area of a worksheet; you can put the list across, but as you learned earlier that’s not the efficient way to maintain any list, so make sure that you enter your list from top down. The first step for setting up a Data Validation list is to call up the Validation dialog, and in the Allow box, select “List”, then in the Source box you can either enter the list range or select it with the mouse. If you want to enter the list range by hand make sure to precede it with an equals sign, or the list range will be interpreted as literal text and that’s what you’ll see in your drop-down. If you have fairly static values you can enter them by hand: Yes,No – Male,Female – Mr.,Mrs.,Miss, etc., but you don’t want to do this for lengthy lists, especially those with values that could change.

Figure 228

- • Using a range reference for a Data Validation list is fine in most cases, but it requires that the list be on the same worksheet as the Data Validation. This isn’t very convenient on something like an order form where several lists might be confusing to users, or worse yet, they could delete or change some of the values. You could hide those list rows/columns, but there is a trick to being able to make Data Validation seamless to your users by using a Named Range. Named Ranges are a great tool for managing end-user applications because they allow you to keep all of your list information, as well as any other details you might want hidden from the users. The first thing you want to do is insert a new blank worksheet (ALT+I+N). Then Cut the list you entered previously and paste it anywhere in the new worksheet (CTRL+X, CTRL+V) Then select the list range and goto Formulas, Define Name (ALT+D+L), and enter a descriptive name in the name box and click OK to add the name.

- • Now you can go back to the worksheet where you want the Data Validation list to appear and invoke the Data Validation dialog again, but this time instead of entering an actual range in the Source box, you’re going to enter =YourListName. When you select the drop-down you’ll now see the same list you did previously, but now it’s out of harm’s way.

Figure 229

- • There’s obviously a lot of Data Validation that we’re not going to talk about here, but you should see that it certainly gives you a great many options for building end-user worksheets, as well as limiting errors.

Inserting and Deleting Ranges, Rows & Columns and Worksheets

Since a big part of building and working with spreadsheets is entering data and formulas, then naturally so is altering them, moving things around, and even deleting elements that you may have already entered. But you can’t just jump into a worksheet and start adding or deleting things without first understanding what implications your actions might have on the rest of the worksheet, and possibly the entire workbook.

- • Inserting Rows & Columns is fairly straightforward (Home, Cells, Insert, or ALT+I+R for Rows and ALT+I+C for columns), but there are a few pointers. Let’s go back to the Cash Flow worksheet as an example. What if you wanted to add some more categories to either the Cash or Purchases lists? It might seem logical that you would go to the first blank cell between the ranges and enter a few rows there. Unfortunately, that’s going to be the long way around. If you proceeded with entering rows below the range, then added in your new categories and values, you would then need to move and update the sub-total formulas, as they won’t recognize the additions to the ranges beneath them. Instead, put your cursor anywhere inside the list range and insert your rows. Not only did you remain in the list, but the formulas automatically updated to include the new rows as well. That is convenient, and more importantly when you let Excel do it, you don’t have to worry about forgetting not to do it. If that happens you now have a potential error between your actual values and what your totals show, and those errors can often be difficult to see, let alone track down. You can do the same thing with columns, just make sure that your active cell is inside the range you want to expand so that the formulas are expanded as well. If you’re not worried about expanding formula ranges, then insert wherever you want provided it doesn’t materially affect another range.

- • Deleting Rows & Columns - (Home, Cells, Delete, or ALT-E-D-R for Rows and ALT-E-D-C for Columns) requires a bit more thought, because one seemingly innocuous deletion could cascade through an entire worksheet or workbook. Going back to the example of the single date entry in the Cash Flow statement, what would happen to all of those dependent cells if you deleted that value? They would all lose the values they derived from that single cell. And think about this: what you delete on one worksheet may have no affect whatsoever on that sheet, but there could be other worksheets that were dependent on it. Unfortunately, by the time you realize it, it may be too late to undo your action, so you close the workbook without saving, hoping you didn’t put too much work into it beforehand. Here is an all too often repeated scenario: many detailed models rely heavily on hidden rows and columns for certain secondary and even tertiary calculations. And just assume for a moment that this is an end-user application, so formula errors have been suppressed (this is often done so that users don’t get the impression that the worksheet is “broken” when they see formula errors). For whatever reason someone deletes some key information, either by deleting cell contents, or columns/rows; the remaining formulas may continue to recalculate, but without those missing components, they may well be calculating incorrectly, if at all. This can cause an organization to make all kinds of false assumptions. More than one million dollar mistake has been made as a result of an incorrect spreadsheet. Do million dollar mistakes happen all the time, no, of course not. Do mistakes of a lesser magnitude happen all the time, absolutely.

- • Nothing substitutes for knowing how your worksheet is designed, but fortunately, you do have some tools that can help you make informed decisions before you delete formulas. On the Formula tab under the Formula Auditing group are the Trace Precedents/Dependents tools. If you ever have a question regarding whether or not it’s safe to delete a formula, then try these tools because they’ll point you to all of the places that your formula goes and where it’s been (note that when a formula reference points to another worksheet, you won’t be told where on the other sheet, just that it’s on another sheet somewhere). Unfortunately, there is no tool to evaluate the effects of deleting rows or columns beforehand. Generally, if you have a command of your spreadsheet, then you’ll have a good idea of what is safe and not safe to delete.

- • Hiding/Unhiding Rows & Columns - This is often necessary to prevent users from seeing certain internal calculations or even creating Custom Views. Many times hiding rows & columns is a better alternative than deleting them. Simply select the row or column range (you don’t need to select the entire row or column, just a single range of cells. E.G. A1:B1 to hide columns A & B; A1:A5 to hide rows 1-5). Once selected goto Home, Cells, Format, Hide & Unhide). In order to unhide you need to select the range to the immediate left and right or top and bottom of the hidden area, so that the hidden area can be included. If you run up against row 1 or column A, you would click the Select All button at the intersection of the Row & Column headers (CTLR+A) and then proceed with unhiding.

- • Shortcuts: ALT+O+R+H or ALT+O+C+H to hide rows & columns; ALT+O+R+U or ALT+O+C+U to unhide.

Deleting Worksheets

- • You can delete a worksheet by right-clicking on the worksheet tab and selecting delete. If the worksheet contains any data then you’ll get a warning prompt. Once you delete a worksheet, there is no undo, other than closing the workbook without saving changes.

Figure 230

- • Should you generally be worried about all of the aforementioned perils of deleting? No, but you should be aware of and mindful of what can happen if you delete dependent components, because there will most likely be more than one occasion that you delete something you can’t get back. This is where the mantra of “Save Often, Save Early” can be a lifesaver, because it can literally determine if you can recover your data or not.

Modifying Data on Multiple Worksheets

- • As we were laying out the Cash Flow worksheet, you were encouraged to make sure that it does what you want before you go and recreate it. In the Cash Flow report’s case you would have recreated it 12 times; one for each subsequent month and one for the yearly summary. In most normal worksheet models you can do a relatively good job of this and be fully prepared when you start creating your copies, but there will arise the occasion where you need to make one or multiple changes to one or more worksheets. The good news is that while other people struggle making those changes to each sheet, one at a time, you’re going to see how to do it all at once. This method works on the method of grouping sheets, in which you can group sheets together. And they don’t need to be contiguous either (you’ll see a good reason for this in a minute). Go ahead and open a new workbook (you don’t need to save it as anything, it’s just for an example). Once it’s open add a few more worksheets to it (you can quickly add a sheet with ALT+I+W, or you can goto Home, Cells, Insert, Sheet).

- • Group All Contiguous Sheets

- • In the new workbook select the first sheet, then hold down the SHIFT key and click on the last sheet tab. You don’t have to select all of the sheets though; the SHIFT key will group the first sheet, the last sheet selected and any sheets in between. You could also right-click on the sheet tab and choose “Select all sheets”, but that groups all of the sheets. Note that the tabs have all turned a different shade; this indicates that they are now grouped, and any change that you make on the active sheet will also be made on the other selected sheets. Go ahead and apply some formatting, add some text, try anything you want, then click on any of the other sheets and see what happened.

- • There are certain things you can’t do to grouped sheets, and once you see the list you’ll realize that it’s pretty reasonable, as most of the exclusions have their own sheet specific parameters, or just have too many potential combinations between sheets to be feasible:

- • Conditional Formatting

- • Format as Table

- • Anything from the Insert Ribbon other than Header & Footer and Signature lines

- • Certain Page Setup elements, like setting the Page Area (but you can by and large apply the same Page Setup properties to all sheets at once! That alone can be a huge timesaver when you’re getting ready to distribute a workbook!)

- • Arranging objects

- • Formula Auditing

- • Anything from the Data tab

- • Protect Worksheets

- • When all of the sheets are grouped, all you need to do to ungroup is select any other sheet.

- • Group Individual (Select) Sheets

- • You’re not limited to grouping all of the worksheets; you can group select sheets as well. One of the most common reasons to group select sheets would be in a finance model that works on a 5-4-4 monthly basis (5 weeks, 4 weeks, 4 weeks in each month – e.g January has 5 weeks, February has 4 weeks and March has 4 weeks, then the process repeats in April, etc.) Given that structure you’ll have 4 months that have 5 weeks, and 8 months that have 4 weeks. You could probably make changes to all the sheets at once for the 4-week months, since you could naturally include the 5-week months, but what about the other way around? So you can group just the 5-week months and apply the necessary changes to those without having to interfere with the 4-week months.

- • To group select sheets you use the CTRL key instead of the SHIFT key, and right-click on each sheet you want to select group. Then make any changes necessary. To ungroup select sheets just activate any of the non-grouped sheets. Activating a grouped sheet will not ungroup them.

Unit Summary: Entering and Manipulating Data (and the basic rules of good spreadsheet design)

- • In this lesson you learned about some of the concepts behind good spreadsheet design, beginning with the initial concept and planning phase, continuing on to design.

- • You saw some of the methods of quickly populating a worksheet with repeating data like months, dates, and even sample data sets.

- • You started working with some simple functions and formulas, and learned about how to copy them around a worksheet utilizing Absolute & Relative Referencing. You also learned the different ways that you can edit existing data and formulas.

- • You learned about how to add your own Custom Lists and use them with AutoFill, as well as some of the user-input features of Data Validation.

- • You saw how to make multiple changes to multiple worksheets at once.

Review Questions – Lesson 5 – Entering & Manipulating Data

1. How do you begin entering text in a cell

a. __________________________________________________

2. How would you enter the same text in multiple cells at once?

a. __________________________________________________

3. How do you begin entering a function/formula?

a. __________________________________________________

4. What are Absolute & Relative References? What symbol characterizes an Absolute Reference?

a. __________________________________________________

5. How would you fill a series starting at 1, ending at 10,000 in increments of 500?

a. __________________________________________________

6. What are some uses for Data Validation?

a. __________________________________________________

7. How would you make changes to sheets 1 & 3 at the same time?

a. __________________________________________________

Lesson Assignment – Lesson 5 – Entering & Manipulating Data

- • Work with the Cash Flow example in the companion workbook to:

- • Populate a range of sample data using RAND().

- • Check out the TODAY() function.

- • Use different AutoSum functions to see how they operate.

- • Enter your own SUM, AVERAGE & COUNT functions.

- • Work with the Lists & AutoFill worksheet to:

- • Enter Months, Days and Dates in different configurations.

- • Try the Fill, Series tools.

- • Practice adding Custom Lists and setting up Data Validation.