Hong has grown up in Guanlubu with many different gods, and paid homage to them in a host of ways. First in each year come the series of celebrations to honor the new year and the first full moon of spring, followed by the Qing-Ming festival in memory of the dead, and the Dragon Boat festival of five-five (the fifth day of the fifth lunar month). This festival, at which boats from different villages race each other on the rivers, honors the loyal but disgraced minister of a ruling house two thousand years before, who committed suicide in a southern stream after writing China’s most celebrated lament. At the Dragon Boat festivals around Canton the people hang rushes and artemisia outside their doors, and offer horn-shaped cakes of sweet and sticky rice to their ancestors before sharing them among themselves, and with family and neighbors, while the children hang amulets and seals on colored threads around their waists. Despite the glory of their boats and their colorful costumes, the men competing for the prizes often erupt in fights, fed by the tension of the times and by old, still smoldering, feuds. Violence has grown so bad that in 1835 the governor from his office in Canton forbids the races to be held, an order that is observed by few, if any, villages.1

After the celebration of the summer solstice, the year starts to turn toward its end. On the sixth day of the seventh month, so it is said, Heaven’s daughter sends down her seven sisters, and so do the women in Hua county prepare festoons of colored silk and gather, in their best clothes, between noon and early afternoon, to worship the visitors and beg their help for skill in needlework. They hire blind singing boys and girls to chant their ballads and on their tables lay out fruit and flowers and pretty ornaments. The next day is double-seven, the festival of the herdboy and the weaving maid, who meet on that day only, using the Milky Way as their bridge. That festival overlaps with the early autumn feast of All Souls, when hungry ghosts are delivered from their anguish by the intercession of the Buddha, in rites first practiced eleven hundred years before. These ceremonies are hardly over when bowls of rice are prepared for all the Buddhist and Taoist monks and nuns and for any beggars in the town, who on seven-ten shall not go hungry.2

At the double-nine, all worship again at ancestral graves, and picnic—if they can—in the hills, to remember the reclusive sage Fei Changfang, who once saved a disciple’s life by urging him to flee to the hills with his young family since death was coming to his home. The disciple followed his advice, keeping his spirits up with chrysanthemum wine, and upon return found all his chickens and farm animals dead in the yard—taken as substitutes, said Fei, since death could not find the humans he was seeking.

A few days later, as the ninth month ends, the Fire God has his festival: for three full days, street by street, people implore his protection, for fire is the worst enemy, one that has leveled towns and villages so many times. For three days lamps blaze all night in streets festooned with streamers, and the residents and shop owners in the wealthier roads stage plays to serve as the “Fire God’s Requiem.” Sometimes of course, as happened in the Dragon Boat races, such ceremonies reverse themselves—in one village near Canton, which celebrated the festival in 1835 with five days and night of plays accompanied by fireworks, the flaming devices set the tents and chests of theatrical clothes on fire, forcing the terrified audience to run for their lives, trampling ten or more in the melee. Just one year later, in a village outside Canton, another crowded theater caught on fire, and this time two hundred men and women were killed in the terrified stampede.3 The festival year ends with the celebration of the winter solstice and its promise of lengthening days, and the visit of the kitchen god, who must be fed and welcomed if his favors are to be granted in the new year.4

In Hua, where heat and hunger, dampness and diseases are never far away, these festivals take on a special urgency. The people of Hua, according to their own early historian, are the kind who will summon a doctor if they have a slight illness, but if their sickness is severe they turn to the spirits. At New Year’s time, before the dawn, they bathe in scented water as the festival begins, and amidst the sound of firecrackers and the drinking of spring wine they weigh the rainfall day by day for twelve days straight, to gauge the coming year’s prospects. Similarly, they chart the wind’s direction, wishing for a cold north wind that will reverse itself and lead to a warm spring, and praying to avoid a southern wind that brings bad luck. Men and women crowd together as they pray before clay figures of water buffalo and their celestial drover; they stage plays in the street to entertain the spirits, scatter pulse and grain on the ground to bring a fertile year, and eat cakes of plain flour and vegetables to keep them free of smallpox. After the first full moon, they welcome the Yellow Emperor by hanging chains of garlic on their doors to ward off evil forces, and cook large round pancakes of sticky rice on which they place a needle and thread, which they say will help them patch the heavens.5

In the fourth month, too, they gather to share a ritual meal, in this case the flavored liquid in which the Buddha’s image has been washed outside the temple gate, and then eat sweet rice cakes cooked with a hundred herbs. Some say this will cure delirium.6 At the summer solstice, they cook and eat dog meat, to keep away malaria, and at the coming of winter they share a broth of meat, peaches, and mustard greens, to keep any other sicknesses away. Even more careful than the procedure followed in the first month is the charting of the rains and wind at the end of the sixth month, on the day they call the Dragon’s Measure. “Heavy rain on this day,” goes the local saying, “means that one will plow the mountaintops; no rain, that one will have to plow the bottoms of the ponds.” But there are other signals from the heavens that must be watched with equal care: a squall that doesn’t last, despite its initial fury; a sudden violent cloudburst, with heavy wind and thunder; or a severed rainbow after rain, known as the Mother of Typhoons, that presages the rage and roar of the fiercest storms that knock down homes and trees, and make travel on the waterways impossible. These are called warnings from Pengzu himself, China’s longest-living patriarch.7

In Hua, the people are told that to avoid poverty they must light huge fires in the street to greet the Yellow Emperor’s arrival, and placate the grain spirits by offering them boiled suckling pig and wine. To further assure good fortune, they should eat dried fish in bulk at the moment of the winter solstice. To place themselves under the Jade Emperor’s protection at year’s end, they burn model houses of bamboo and stay awake all night, hang strings of oranges before their doors, and carve peachwood charms for the gods of the gate. To keep cold winds away, they eat boiled noodles cooked in ritual vessels. To greet the moon in the middle of the autumn, they prepare three separate types of mooncakes, called “goosefat,” “hardskin,” and “soft skin” cakes, ranging in weight from an ounce or two to several pounds, some sweet, some salt, their surfaces decorated with multicolored pictures of humans and animals. Eaten as the lanterns are hoisted high to greet the moon, these cakes bring promise of early marriage and plenteous children.8

Animals and birds, mythical or real, are an inextricable part of these relations with the spirit worlds. Dragons are linked through ceremonies to certain days of the year, when the way they are propitiated can determine the force of the sun or prevent the rain clouds from forming and releasing their bounty; at the winter solstice, for instance, “the hidden dragon represents the Celestial Breath which returns to the point of its departure.” In this role, the dragon stands for the yang force of the east, the strength of sun and light.9

The tiger and the cock each features prominently in many ways and guises, also linked to the changing cycles of the seasons, especially the passage from winter into spring. Because of stories from antiquity, the tiger is often associated with a giant peach tree, under which he stands at the eastern corner of the world waiting to eat the spectral victims bound and passed on to him by two divine protectors of the human race. By association of ideas—and lacking real tigers—the magistrates often place peachwood images of human guardians outside their formal office entrances, and painted tigers on the lintels, from which also dangle the ropes of reed or rush in which the specters had once been bound. The specters entering the tiger’s maw had approached the peach tree from the northeast, and thus the tiger came to represent the yang force vanquishing the powers of winter, cold, and yin (the north).10

The red color of peach can counteract evil. Strips of red paper on a house door are effective substitutes for peachwood images, just as peach twigs can serve in exorcism, and even the roughest picture of a tiger guard a house from harm, as infants might also be protected by wearing a simple “tiger hat.”11 A white tiger, however, represents different kinds of danger—it is linked to the stratagems and the violence of war, the thirst for blood, and also can bring mortal danger to infants and to pregnant women. With its name linked to certain so-called baleful stars, the white tiger figures centrally in astrologers’ calculations of avoiding disaster. Thus can a spirit considered the protector become, in altered guise, a force of death and destruction.12

The cock looms large in local consciousness as well. Sometimes it is sacrificed, its blood smeared over door lintels to give protection, the very lintels on which the tiger images are hanging. In early tales, the cock presided in the tree under which the tiger ate his victims. “In the mountain or land of the peach capital is a big peach tree with a foliage extending over three thousand miles. A gold cock is perched upon it, and crows at dawn.”13 Even though the blood of freshly killed cocks can help exorcise demons, they must not be slain on the first days of the year, when only their presence can provide the force to counteract the demons escaping the tiger’s jaws. At other times, cocks—especially those of reddish color—would be sacrificed to the sun, a practice some ascribed to the ancient state of Lu, where Confucius was born and where he taught, “because its voice in the morning and its red feathers drove evil from the rulers of that state.” Like the peach, it was observed, “the cock dispels disease on account of its solar propensities, and moreover confers on man the vitality bestowed by the universal source of life, of which it is the symbol.”14

The category of religious books known as the Jade Record also chart the course of every year, although in harsher ways, as they present the march of souls through hell. The prologues to the Jade Record state that the central holy text was sent down to earth by the being termed the Highest God, after being submitted to him by Yan Luo, the king of hell, and by Pusa, the compassionate Bodhisattva. The purpose of the text is to clarify for all human beings the relationship between bad deeds on earth and suffering in hell after death, and to show how suffering can be averted by good actions on earth. In dealing thus with the world of hell, and with the souls of the dead, the text deliberately reverses the well-known words of Confucius, who had always said to his disciples that since we cannot even fully understand life on earth, how can we presume to discuss the gods or the afterlife?15

In line with these principles, tradition says that the text of the Jade Record was initially given not to a Confucian worthy but to a Buddhist priest, and by him passed on to a wandering Taoist. As stated in the book itself, this was in the reign period of Taiping, or “Great Peace,” a title adopted by both the Chinese Song emperors and the barbarian Liao invaders, a dual coincidence that allowed ingenious scholars to place the heavenly transmissions with precision to the years of 982 and 1030. All who read and absorb the message of the Jade Record, and print extra copies so that others too may read and learn, will not only escape the worst torments of hell, and bring prosperity to their families and descendants, but in the transmigration of their souls may be reborn as human beings, or even move to higher stages of life—men to the happy lands, and women to the life of men. Those who ignore, deface, or mock the tracts will find no such mercy, but be condemned at death to descend to the lower layers of hell and, according to their crimes on earth, move through each of the ten hellish palaces in turn.16

Pictures in the Jade Record show, for those who cannot read, how the judged souls are transformed. Only a few return as happy, healthy humans. Of the others, some are allowed to stay human, yes, but condemned to be ugly, misshapen, poor, and ill; while many, according to their sins, return as horses, dogs, birds, fish, or creeping things.17 Copies of the Jade Record are everywhere as Hong Huoxiu is growing up, since editions begin to proliferate just in the years when he is preparing for his exams, even though the sixteen maxims that the scholars read aloud to educate the people include a ringing condemnation of the Jade Emperor and the books issued in his name.18

The calendar printed in each Jade Record devotes the first day of the first lunar month to the Maitreya Buddha, the Buddha of the future, whose plump, smiling presence can be found in many a temple, and whose protection can be sought by prayer and intercession, and by taking on this day a vow to respect heaven. The eighth day, in contrast, belongs to Yan Luo, known to all as the king of hell. Strangely, though, the Jade Record notes that Yan Luo has lost his former proud position as lord of the first of the hellish palaces. In that role, long ago, he proved too compassionate to those who had been unjustly killed, and allowed them simply to return to earth again to lead new lives. For this error of compassion the Highest God demoted him to the fifth palace, where he now presides, though it is his name above all others that still stands for hell itself. In the sixteen dungeons of his hell, his minion devils tear out the hearts of those who committed any one of a varied group of crimes: whose faith in the Buddha is weak, who while on earth did not believe in retribution, who killed live creatures, or who broke their word, used magic arts, wished death to others, forcibly or guilefully seduced the innocent, cheated in business, let their neighbors die, spread discord, or nursed their rancorous hearts in other ways.

Outside his dungeons Yan Luo has built a tower, which he calls his “Tower to View the World,” a tower shaped like a bow, eighty-one units of distance around, the back like a taut string facing toward the north, the curved front spanning east and south and west. Sixty-three steps lead to its summit, forty-nine measures above the ground of hell, and to this lofty eminence the tormented souls are led by their demon guardians, so that, all unseen, they can gaze upon the earthly families they have been forced by death to leave.* And with the wisdom of death and Yan Luo’s help they see how their dear children and closest relatives, heads bent over the departed one’s coffin in apparent mourning, in fact are cursing the dead one’s memory, defying his instructions, selling off the goods and property he so painfully acquired, and battling through lawsuits for what is left.19 Tormented by these visions of life on earth, they are assigned by Yan Luo to his sixteen separate dungeons, where they join the bandits and prostitutes on whom Yan Luo did not waste the subtler sorrows of the tower. Here, the guilty souls are seated on iron blocks and tied to metal pillars with copper chains. With small, sharp knives the demons slice their chests and bellies, and tug the hearts out with a hook. As the souls look on in agony, the hearts are sliced in pieces and fed to a crowd of waiting wolves and serpents.20

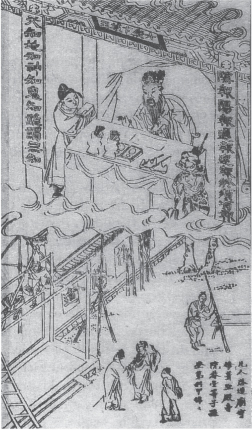

The sixth court of hell, as portrayed in a nineteenth-century edition of the Jade Record. These tracts, representing the teachings of moralistic forms of folk-Buddhism, circulated widely in South China during Hong Xiuquan’s youth. After his conversion to Christianity, Hong argued that all such tracts should be destroyed. The illustration above shows the underworld king Bian-cheng sitting at his desk as he presides over the sixth court of hell. He is flanked by his two assistants, one in scholar’s garb to summarize the dead person’s record on earth, and one in demon form to supervise the appropriate punishments. The accompanying illustration shows four of the sixteen torments that are imposed on sinners by King Biancheng: hammering metal spikes into the body, flaying alive, sawing the body in half vertically, and kneeling on heaps of metal filings.

After passing through all the ten levels of hell, the dead proceed to the palace of the goddess Meng, where they receive a potion of forgetfulness before their souls transmigrate back to earth for a new cycle of life, as insect, bird, animal, poor human, or rich, according to their deserts. This process is presided over by the two demon-spirits shown here. Though the exact details vary in different texts, “Life-is-short” (top) usually wears dark clothes, is armed, and laughs uproariously. “Death-has-gradations” (bottom, sometimes rendered as “Death-comes-swiftly”) is always dressed in white, wears a conical white hat, wails continuously, and carries an abacus to tally the exact amount of each person’s sins. Courtesy of Yale University Library.

Only one day after King Yan Luo’s feast, on the ninth day of the first month, comes the day of the Highest God, also called the Jade Emperor, or, in combination, “Jade Emperor the Highest God.” For him, the vows that must be made are those of loyalty and filial devotion, for his power exceeds that of all the others, though his exact origins are vague. According to common tradition, the future Jade Emperor was conceived by his royal mother after a dream, in which she was visited by Lao Zi, Confucius’ contemporary, and the earliest great philosopher of the religion later known as Taoism. The babe was born on the ninth day of the first month, at noon, and at the moment of his birth the splendor from his body filled the whole land. During his princely childhood, he was endowed with sublime intelligence, and showed himself at all times loving and compassionate, distributing his goods and the surplus of the treasury to the poor, the sick, the widows, and the orphans. Called to ascend the throne after the death of the king, his “father,” he handed over the government to his ministers, and withdrew to the mountains to a life of religious contemplation. Achieving a state of perfection, he attained immortal life in heaven, but chose to revisit earth in three protracted cycles of eight hundred visits each; during these forays back to earth, he preached his doctrine of compassion and salvation, healed the sick, and taught the people. By a series of imperial decrees issued between the years 1015 and 1017 by the Song dynasty emperor Zhenzong, this figure was officially deified as the Celestial Jade Great Ruler of Heaven.21

Under the Highest God’s general supervision, each of the other nine gods of hell—just like Yan Luo—has his holy day, and an invocation that, if correctly and respectfully uttered, may ward off his rage. Cumulatively, among themselves, they judge every foible of which humans are capable, and few will escape being punished by them. The role of the god who rules the first hell is preliminary scrutiny of the newly dead, prior to passing them on to others: in his palace hangs a mirror, called the Mirror of Reflection, where all must see their own sins through their own eyes. Most are pushed on at once to the other palaces of hell, where their specific sins are dealt with, but two groups are kept for further suffering through thought: the first is composed of those who killed themselves without good reason, out of petty spite or sputtering anger, not because of unbearable hardship or humiliation. In taking their lives for inadequate reasons, such people betrayed both the gods of the land who gave them existence and the parents who spawned and raised them; for this ingratitude, they must, once in every twelve-day cycle, endlessly relive the exact suffering that led them to the act of suicide itself. Those in the other group are Buddhist and Taoist priests who were careless in their chanting of holy texts, or took money for their services, or deceived the gullible; each is enclosed in a narrow cell lit only by a guttering lamp with an endless line of wick and a hundred pints of lamp oil, until every word of the sacred books has been read aloud correctly.22

As for the other palaces of hell, all those who have not lived purely and thus could not avoid the mirror’s judgments, must face their suffering in turn. Thither go the quack doctors who in search of profit harm their patients, the priests who deceive children of either sex to be their acolytes, people who sequester others’ scrolls or pictures, marriage go-betweens who lie about their clients’ charms.23 Hither come shop clerks who deceive their customers, prisoners rightfully condemned who escape from jail or exile, grave robbers, tax evaders, posters of abusive bills, and negotiators of divorce.24 Hither come those who won’t yield the right-of-way to those who are crippled, who steal flagstones from the road and tiles from public buildings, who refuse to help the sick, who sell fake medicines or debase the quality of silver, who foul the streets with filth. The rich who forcibly build on the land of the poor, the careless or mischievous who set fire to hillsides or to property, the killers of birds, the poisoners of water, the destroyers of religious images, the defacers of books, the writers and readers of obscene literature, the hoarders of grain, the heavy drinkers, spend thrifts, thieves, bullies, the drowners of baby girls, the killers of slaves, gamblers, lazy teachers, neglectors of parents—all, all, all shall suffer the penalties due them. The Jade Record lists every punishment for every category, the suffocating and the lacerating, the slicing and the burning, the breaking of bones and the yanking of teeth, snakes in the nostrils and worms in the brain, severing the penis, smashing the knees, pulling the tongue, tearing out nails, scratching out eyes—until the mind staggers under the horror of it all.25

Yet it is a melancholy truth that the world in and around Canton provides violent deaths enough to test the mettle of all ten kings of hell and to wear the treads on the stairs of King Yan Luo’s Tower to View the World. The Canton authorities execute hundreds of their people for violent crimes each year, and both these killers and their victims must face judgment once again in the courts below the earth.26 Often there has been both public spectacle and retribution, as with the Canton wife condemned to death by slicing because she killed her husband. Huge crowds assembled to watch her death, drawn, it is said, by her pride and fierceness, her amazing beauty, and the tiny size of her feet.27 Crowds gather too to see a woman who murdered her mother-in-law executed in her husband’s presence, and to watch as a member of the pirate gang that killed twelve innocent foreign seamen is executed by being nailed to a giant cross.28

Others around Canton have committed crimes for which punishment both on earth and in the realms of hell seems justified to their contemporaries. The men who pose as regular sedan chair carriers, using their disguise to kidnap and sell blind singing girls; the Buddhist priest who runs a den of thieves from his temple outside the city’s eastern gate; those who rob the local graves not only of the ritual objects that might be buried there but of parts of bodies, to practice their “murdering, diabolical and magical arts.”29

Other gods and spirits have their places and their days in the Jade Record: Guanyin, the compassionate Bodhisattva of mercy, and the Buddha Sakyamuni have two days each, one for the day of their earthly birth and one for the day on which they achieved enlightenment; the kitchen god has two as well, once for his birthdate and once for the day at the end of the year when he reports back to heaven what he has seen down here on earth. The city god has his day in the middle of summer, as do the local gods of the soil, in the middle of spring. The goddess Meng has her day on the thirteenth of the ninth month. Her role is a central one, for in the ten reaches of hell where the dead souls wander and suffer, the focus of the other gods is on judgment and remembrance, so that all human souls can be punished until the record is clear. But Meng’s role is to induce forgetfulness, so that those born again to various forms of life on earth will not be burdened—or overgifted—with earlier memories.

Goddess Meng’s Tower of Forgetting, subdivided into 108 chambers, lies just beyond the tenth palace of hell, where all souls have received their final decisions on reincarnation. In every chamber of her domain her demons lay out cups of the “wine that is not wine,” and every soul that enters is forced to drink. As they drink, their past lives vanish from their senses, they are stripped clear of memory, and tossed into the red waters of hell’s last river. Borne by the current, they are washed ashore at the foot of a red wall, on which a message four columns long is hung: “To be a human is easy, to live a human life is hard; to desire to be human a second time, we fear is even harder. If you wish to be born into the Happy Lands, there is one easy way—say what is really in your heart, then you’ll reach your goal.” Two demons then haul them ashore, to send them on to their newly allotted spans. One demon is tall, round-eyed and laughs uproariously; he is in a fine robe, with a black scholar’s hat on his head, writing brush and paper in his hands, a sword on his back. His name is Life-is-short. The other is dressed in soiled cotton clothes, blood flows from his head, he furrows his brows and loudly sighs, carries an abacus for calculations, and has an old rice bag slung around his shoulders in which he stuffs scrap paper. His name is Death-has-gradations.30

There is one group of souls, the Jade Record tells us, who after they have passed through all the trials, and been prepared for their return to earth, petition the demons to stay as ghostly souls a while longer, before regaining their corporeal forms, and sometimes their petition is granted. These are women who have been so badly treated by men in their former lives that they wish to return as ghosts to get revenge. Some were falsely promised marriage then betrayed, some were seduced, some were promised they would be the principal wife and found other consorts already in the home. Some were widows, promised shelter for their aged parents, or succor for their children from a former marriage, and for these or other reasons, when humiliated or betrayed, took their own lives. If the men who wronged them so on earth are about to sit for the examinations, and the women succeed in getting the demon’s permission to delay return in bodily form, as soon as the evildoers congregate in the examination halls the women will hasten thither. Then in their formless state they will enter the halls and approach their abusers, now their victims, and addle their minds and misguide their writing brushes, so that they have no chance of passing. The men faced with this disaster have one way out: on the seventeenth day of the fourth month, on the holy day for the king of the tenth and last palace in hell, if they worship him sincerely, and promise to reform themselves and live by the precepts of the Jade Record, then they can pass their examinations and be safe at once from the women’s shades, the exactions of the Mandarins, and the dangers of flood and fire.31

Once the New Year’s festivities of 1837 are over, Hong Huoxiu yet again takes the qualifying examinations in Hua county. He passes this early round and, as he did in 1836, takes leave of his family, and travels to Canton for the second stage. This time, the pressures in the city are even higher than the year before. The literary director of Canton has warned of the prevalence of dishonesty among the licentiates in his region, and announced that any candidates offering bribes to have their papers given special commendation will be strictly punished. Mockingly, he records the euphemisms given by the candidates as they seek his special favor: “conveying expenses,” “book gold,” or “small expenses for opening the door.”32 In contrast to the previous year, no foreign tracts are being distributed, and so many Canton printers have been rounded up that it is hard for publishers to meet their deadlines. Yet the Jade Record still circulates, assuring the hopeful that one sure way to attain examination success is to follow its admonitions for a virtuous life, and giving numerous examples from previous reigns to ram the moral point home.33

Late in the second lunar month of 1837, Hong learns that despite his success in Hua he has yet again failed the round of examinations in Canton. Feeling too ill to make the long walk home, he hires a sedan chair with two bearers, reaching Guanlubu on the first day of the third month, the birthdate of the king of the second hell, who punishes the purveyors of false hopes. Now too weak to move, Hong goes to bed.34 A great crowd gathers around his bed, summoning him to visit King Yan Luo in hell. It is a dream, but Hong sees it as the warning of the end. He calls his family to him, and his two elder brothers hold him half upright in the bed. Hong’s parting words, as remembered by his cousin, are these: “My days are counted, and my life will soon be closed. O my parents! How badly have I returned the favour of your love to me! I shall never attain a name that may reflect its lustre upon you.”35 Hong’s wife, too, is weeping by the bed, and to her Hong says, “You are my wife. You must not remarry. You are now pregnant and we do not know whether you will bear a son or daughter. If it is a son, let my elder brothers look after you, and do not remarry. If it is a daughter, do likewise.”36

Hong lies back on the bed, too weak to say more, and the family realize that he is about to die. His body is still, his eyes are closed. In his crowded brain, another throng assembles. There are men playing music. There are children in yellow robes. There is a cock. There is a tiger. There is a dragon. Attendants bring a sedan chair, in which Hong takes his seat. Borne aloft on their shoulders, accompanied by his varied retinue, Hong is carried away toward the east.37

Inside his sedan chair, Hong stirs in fear. But when the procession halts at the great gates, the crowd is bathed in light, and welcoming. The attendants who greet him wear dragon robes and horn-brimmed hats, not the martial dress of Life-is-short, or the soiled motley of Death-has-gradations. Though they slit him open, like the fiends in hell, it is not to torment him but only to remove the soiled mass within, which they at once replace with new organs, sealing the wound as though it had never been. The texts they unroll slowly from a scroll before his eyes are clear to read, not distorted by a sputtering wick, and he absorbs them fully, one by one.

His reading finished, a woman comes to greet him. She is not the goddess Meng, forcing him to drink beakers of forgetfulness on the edge of a blood-colored stream. For this woman calls him “son,” and herself his mother. “Your body is soiled from your descent into the world,” she tells him. “Let your mother cleanse you in the river, after which you can go to see your father.”38

Hong sees that his father is tall, and sits erect, his hands upon his knees. He wears a black dragon robe and high-brimmed hat. His mouth is almost hidden by his luxuriant golden beard, which reaches down to his belly. There are tears of anger and of sorrow in his eyes as he addresses Hong, who prostrates himself before him, then stands to one side in reverent attention.39

“So you have come back up?” says his father. “Pay close attention to what I say. Many of those on earth have lost their original natures. Which of those people on earth did I not give life to, and succor? Which of them did not eat my food and wear my clothing? Which of them has not received my blessing?” Again he asks, “Have they no scrap of respect or fear of me?” Hong stands attentively. “It is the demon devils who have led them astray,” says his father. “The people dissipate in offerings to the demon devils things that I have bestowed on them, as if it was the demon devils that had given life to them and nourished them. People have no inkling as to how these demon devils will snare and destroy them, nor can they understand the extent of my anger and my pity.”40

Moved to outrage by his father’s grief, Hong offers to start at once arousing and enlightening people to the demon devils’ evil ways, but his father checks him saying, “That will be hard indeed.” He shows his son the myriad ways the devil demons harm the people on the earth. The son sees how the father, unable to bear looking any more, turns his head away from the sight in sorrow.41

Angered also by the tragic sight, Hong asks his father, “Father, if they are as bad as this, why don’t you destroy them?” Because, comes the reply, the devil demons not only fill the world; they have forced their way even into the thirty-three layers of heaven itself. “But father,” Hong asks again, “your power is so vast that you can give life to those you want to have life, and death to those you think should die. Why then allow them to force their way in here?” “Wait,” says the father. “Let them do their evil a little longer. They shall not escape my wrath.” But, says Hong, if they keep on waiting, those he loves on earth are only going to suffer more. If you find the evil intolerable, replies his father, then you may act.42

Hong watches the demons carefully, and sees that the leader is Yan Luo, the king of hell, whom people on earth call also the Dragon Demon of the Eastern Sea. Again, he begs his father for permission to do battle, and this time it is granted. To help him in the struggle, his father gives him two gifts, a golden seal and a great sword called Snow-in-the-clouds. With the sword and seal, Hong goes to war on his father’s behalf. Up they fight, through the thirty-three levels of Heaven; he wields the sword; his elder brother stands behind him, holding the golden seal, the blazing light from which dazzles the demons and forces them into flight. When Hong’s arms grow weary, and he has to rest, the women of Heaven surround him and protect him, reviving his strength with gifts of yellow fruits. When he is rested, they return to battle together, and fight on side by side. Devious is King Yan Luo, and capable of endless transformations—now he appears as a great serpent, now as a flea on the back of a dog, now as a flock of birds, and now as a lion. Forced slowly down through the many levels of Heaven, at last the demons are driven down to earth itself, and there Hong and his celestial army behead them in great numbers. At one moment, Yan Luo himself is in Hong’s grasp, but Hong’s father orders his son to let the demon go, for such a captive would pollute the very heavens, and in his guise as serpent might mislead people still, and eat their souls. Protesting but obedient, Hong spares the devil king. As to Yan Luo’s minions, all those that Hong can find in the world below, his father lets him slay.43

With the great battle over, although the final outcome still is unresolved, Hong rests in Heaven. He lives in his palace in Heaven’s eastern reaches, with his wife, the First Chief Moon. She tends him lovingly, and bears him a son, whom they have yet to name. Their Heaven is full of music, and Hong finds it easy to forget the world from which he came. Patiently, his father guides him through another group of moral texts, awaiting his transformation. When Hong remains unchanged, his father guides him word by word, till understanding comes. His elder brother is less patient, and grows furious at his obtuseness. At such times Hong’s elder brother’s wife acts as mediator, placating her husband and reassuring Hong. Hong comes, in time, to see this elder sister-in-law as his second mother.44

Despite these joys and studies, Hong’s father will not let his son forget the world below. Hong must return to earth, his father says, the demons still are strong, and the people there debauched. Without Hong, how will they be transformed? Before he goes back to earth, Hong’s father adds, he must change his name. The name of Hong Huoxiu is no longer fitting; it violates taboos. Instead of the Huo, or “fire,” in Hong Huoxiu, the father orders him to use the name “completeness,” quan. Hong himself can choose any one of three ways to use this name, his father tells him. He can keep the new name secret from the world, and style himself Hong Xiu. He can jettison both his earlier given names, and style himself Hong Quan. Or he can keep the non-tabooed given name, and call himself Hong Xiuquan. To prepare for the return to earth, his father combines Hong’s new name with a formal title, reflecting his newfound power and dignity: “Heavenly King, Lord of the Kingly Way, Quan.”45 And as another parting gift, the father chants two poems that he has composed for his son, to take with him on his journey back below. Their meaning now seems shrouded in mystery, he says, but one day they will become clear.

Hong takes the gifts and says farewell to his wife and son, who cannot accompany him on the long journey to earth. They must stay in Heaven with Hong’s parents, and Hong’s elder brother, wife and children. There will they find comfort and safety till Hong returns from earth in glory. In final benediction, Hong’s father reassures his son, “Fear not, and act bravely. In times of trouble, I will be your protector, whether they assail you from the left side or the right. What need you fear?”46

Hong’s earthly family have watched over him day and night as he sleeps and wakes and sleeps again. Now he is deadly quiet; now he shouts out excitedly, “Slash the demons. Slash the demons,” pointing to “one here, one there,” as they wing their way past him, and crying out that none of them can resist the blows of his sword. Now he leaps from his bed and runs around his room, shouting battle cries and moving his arms as if in combat; now he falls back again, silent and exhausted. Repeatedly, he sings the same two lines from a popular local song: “The victorious swain travels over rivers and seas /He saves his friends and kills his enemies.”47 Sometimes he addresses himself as Emperor of China, and is delighted when others do the same. He writes out in red ink the words of his new title, “Heavenly King, Lord of the Kingly Way, Quan,” and posts it on his door. For his older sister, Hong Xinying, he writes the four characters of an alternate title he has adopted, “Son of Heaven in the Period of Great Peace.” To other visitors he sings aloud what he has learned to be “the sounds of high heaven.” He openly contradicts his own father, and denies that he is his father’s son. He argues with his older brothers. Father, sister, brothers, visitors, all feel the bite of his tongue, and hear his assertions of his duty to judge the world, to separate out the demons from the virtuous. He remembers and writes down poems that he composed during those sky-war days and nights. One goes:

My hand grasps the killing power in Heaven and earth;

To behead the evil ones, spare the just, and ease the people’s sorrow.

My eyes roam north and west, beyond the rivers and mountains,

My voice booms east and south, to the edge of the sun and moon.48

Another has these lines:

With the three-foot blade in my hand I bring peace to the mountains and rivers,

All peoples living as one, united in kindness.

Seizing the evil demons I send them back to earth,

And scoop up the last of the evildoers in a heavenly net.49

His own closest relatives and the people in Guanlubu village murmur that Hong Xiuquan may be mad. His brothers take turns to see that the door to his room is kept shut, and that he does not escape from the house. Such precautions are essential. Chinese law holds all family members responsible for any acts of violence committed by an insane person. If a madman kills, all his family members will pay the penalty.50

Yet slowly Hong Xiuquan calms down. Family and friends grow used to his new name. His wife, Lai, bears him a baby girl. He returns to his Confucian texts, and begins to prepare yet again for the examinations. He resumes his teaching duties at a nearby village. The dream is beyond interpretation, and therefore by common consent it can have no meaning.51

* As with many other numbers in these texts, we are here being presented with mystical multiplications of the numbers seven and nine.