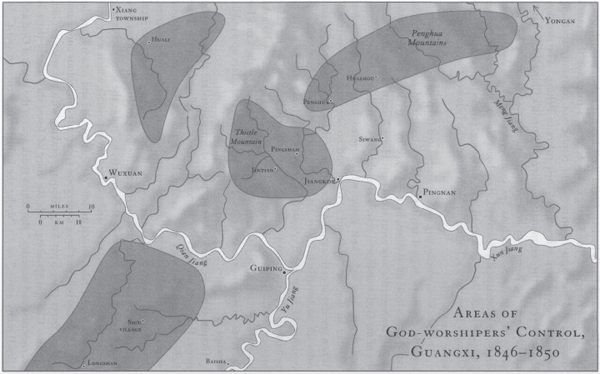

By the late summer of 1849, when Hong and Feng are back in Guangxi, there are four distinct centers of the God-worshipers, grouped in a rough semicircle to the north and the west of the district city of Guiping. The four regions—measuring from their outer edges—cover an area some sixty miles from east to west, and eighty miles from north to south. One of the centers remains on Thistle Mountain, but now includes the prosperous village of Jintian on the plain at the foot of the mountains. One encircles the area of Sigu village, where Hong long found support from the God-worshiping Huang family. One, more to the northwest, includes a network of mountain villages under the jurisdiction of Xiang township, where Hong and Feng destroyed the image of King Gan. And one newly expanding area, northeast of Thistle Mountain, sprawls through the Penghua Mountain chain, incorporating the little market towns of Penghua and Huazhou.1

Though the God-worshipers themselves are still seen by their neighbors and by the officials of the Qing state as mainly a religious group, not yet an emergency calling for direct military suppression, the area as a whole has been racked by at least a dozen risings of bandit groups connected to the Heaven-and-Earth Society. China itself has more than enough troubles in other regions, but Guangxi has become a focus for the court’s concern, and messages of anxiety and resolve are constantly speeding between the southern officials and their rulers in Peking.2 The decision the same year by the commanding officers of Britain’s China fleet—based mainly in Hong Kong—to make a final, all-out assault on the Chinese pirate bases in the South China Sea, brings yet more chaos. As the pirate bases are systematically destroyed, their boats blown up, and their storage bases and safe havens burned, the surviving pirates move upriver to Guangxi from the sea, linking up with those who followed the same route some years before.3

The four God-worshiping areas are separated from each other by intermediate zones of rugged territory that are controlled either by hostile, non-Hakka local inhabitants, by bandits, or by wary local officials. Journeying between the four areas is not easy. Hong Xiuquan, like other leaders of the God-worshipers, travels at night, between eleven in the evening and dawn, in a tight-knit group with covered lanterns, “all bunched together so that no one is out in front, and no one lingers in the rear.”4 When one day in early autumn Hong violates these safety procedures, and rides off on horseback before his designated companions have collected together, he is yet again accosted by robbers, and lucky that he survives unharmed. For this impetuosity, he is publicly reprimanded by his elder brother Jesus—speaking through the lips of Xiao Chaogui—who asks how Hong dares to break such a simple order, devised by the Lord for the protection of the true believers. Hong is contrite, and offers up a public apology.5

Despite the risks, the leaders of the God-worshipers are always on the move. For their believers are scattered in isolated villages, and the True Religion blurs constantly with local folk practices, beliefs, and shamanic voices, just as the “converts” themselves are often suspect for their motives, devotion, or sincerity. Hong is aware of the dissensions between local groupings, and one of his tasks is to examine the prophetic utterances they have issued in their trances or their ecstasy, to “judge the spirits according to the truth of the doctrine” and to ascertain if possible which were true and which were false, which indeed “came from God and which from the devil.”6 Some believers have undergone apparently miraculous cures, and if these cures come from Yang Xiuqing speaking with the voice of God, or Xiao Chaogui speaking with the voice of Jesus, then surely there is “earnestness and sincerity.” But others speak against the word of God and “[lead] many astray,” or act “under the influence of a corrupt spirit.” In such difficult cases, no one, according to Hong’s contemporaries, “was so able as he to exercise authority, and carry into effect a rigid discipline among so many sorts of people.”7 In the Taiping’s own text that records this era of Hong’s work, Jesus declares (through Xiao), “It is because the hearts of the congregations are not totally committed to belief in the Doctrine that I want Hong and you others to go to different areas and dwell there. . . . Those who currently believe the True Doctrine are few indeed—they may revere half of it, but they reject the other half. Are you able to win over all their hearts?” And though the leaders duly respond, “We cannot win them over completely,” they accept the charge that Jesus gives them.8

Another reason for constantly traveling among the four base areas of the God-worshipers is money, the money for living expenses, for printing tracts, for helping the destitute or the victimized who are beginning to drift to the four areas from the surrounding countryside, for making or buying the simple weapons that are needed for local defense, for establishing emergency grain supplies in the face of the famine conditions endemic to the region, and for buying the freedom of those God-worshipers unfortunate enough to be imprisoned. Local gentry like Wang Zuoxin, angered by the disruptive and destructive effects of the God-worshipers on their communities, and by what they felt were affronts to fundamental Chinese moral values, were able in 1847 and 1848 to have Feng Yunshan imprisoned, and his colleague Lu Liu so mistreated that he died in prison. In the summer of 1849, following another clash and flaring of local angers, Wang Zuoxin is able to have two more God-worshipers confined to jail. One of the captives is the same young man Hong Xiuquan successfully petitioned the magistrate to release five years before, but now angers are deeper and stakes higher, and neither elegant petitions nor the arguments from international treaty law used to free Feng Yunshan are of any use. To raise the money needed for the two men’s release, the leaders of the God-worshipers invoke the sufferings of Jesus on the cross, pointing out that though such suffering purified the sufferer, and might have to be endured by all God-worshipers in their quest for salvation, it was still right to evade it for the captured brethren. Xiao Chaogui, speaking again with the voice of Jesus, suggests that all those with stores of rice donate half of them to try and buy the men’s release.9

At other times the God-worshipers exhort their congregations with moral arguments, blaming them for weakness of will, stinginess, and for cheating Heaven if they withhold their cash.10 They also urge certain of the wealthiest families among the God-worshipers, like the Shi clan, whose home is near the Huangs’ in Sigu village, to give major donations to effect the release of the imprisoned men, telling the potential donors that it is the express will of God that they make these donations. In many of these exhortations the leaders now refer to God by the oddly informal name of the Old One on High; by doing this, the petitioners seem to have been emphasizing that this was all an extended family matter.11 At yet other times, without great subtlety, the appeals for cash donations from the congregations are made in the same breath as decrees ordering savage punishments for those guilty of immorality. Either enough money cannot be raised or the officials cannot be bribed, for the appeals for funds for these particular men’s release stop by the end of the month, when the God-worshipers learn that their two imprisoned friends have been beaten or tortured to death. But within a month, two more prominent God-worshipers are arrested at local gentry urging, and the process has to begin all over again.12

This whole grim episode shows that during 1849 the God-worshipers could not yet rely on a strong financial base, and underlines the importance of those wealthy families who had already joined the movement. One of these was the Shi family, Hakkas who provided not only large amounts of money but in the person of one of their young men, Shi Dakai, only nineteen at this time, gave Hong Xiuquan a passionately devoted follower, who was later to become one of his finest generals. The Wei family, from Jintian village, owned large holdings of rice paddy, and also operated a pawnshop or shops; they were apparently drawn to the God-worshipers because despite their wealth they were unable to rise in the local hierarchies, owing to their lowly status as the “runners” or junior lictors in the local government office, and because they were of mixed blood, having at some stage in the past intermarried with local Zhuang tribesmen. There was also the Hu family, who often gave shelter to Hong Xiuquan and had extensive landholdings in both Pingnan and Guiping districts, as well as having held minor military office.13 Yet the God-worshiping leaders, at least through the month of February 1850, did not want such backers’ generosity to be widely known; and in that month, when the Hus offered to sell off their land, and to donate the proceeds along with their other property to the God-worshipers, so as to “further the Heavenly Father and Heavenly Elder Brothers’ enterprise,” they were warmly thanked for their loyalty and generosity but asked to keep the gift “completely secret” for the time being.14

Perhaps the agonizing and ultimately fruitless quest during 1849 for the release of their two imprisoned followers was the decisive factor that drove the God-worshiper leaders into a formal anti-government stance. Ever since his dream of 1837, Hong Xiuquan had been preaching against the “demon devils,” even though it was never quite clear who these devils were, whether they were the physical forms of the followers of the devil king Yan Luo himself, or benighted Confucian scholars who closed their eyes to truth, or Taoist and Buddhist priests, or the shamans of local folk cults, or the sinners and idolaters who broke the various versions of Hong’s or God’s commandments. Sometimes Hong was totally inclusive in his definitions, as in remarks he made at Guanlubu in 1848 or early 1849: “Those who believe not in the true doctrine of God and Jesus, though they be old acquaintances, are still no friends of mine, but they are demons.”15 At other times his definitions edged into broader zones of criticism, closer to the Protestant idea of predestination, as in one of his favorite chants, which he composed during this same period:

Those who truly believe in God are indeed the sons and daughters of God; whatever locality they come from, they have come from Heaven, and no matter where they are going they will ascend to Heaven.

Those who worship the demon devils are truly the pawns and slaves of the demon devils; from the moment of birth they are deluded by devils, and at the day of their death the devils will drag them away.16

By the end of 1849 or the beginning of 1850 it is the Manchu conquerors of China, and those officials serving them, who are now often identified specifically as the demons to be exterminated, and the Qing courts where God-worshipers are brought to trial on “trumped-up charges” are now described by Hong as presided over by “demon officials.”17 Part of the change lies in Hong Xiuquan’s own mood. At this same time he is reported to have said, “Too much patience and humility do not suit our present times, for therewith it would be impossible to manage this perverted generation.”18 Perhaps Hong thinks indeed that the God-worshipers have shown more than enough patience in the face of local hostility, or the local officials’ connivance with that same local hostility.

If the time for “patience and humility” was over, and if many people had become “the pawns and slaves of the demon devils,” one could see the Chinese people as the enslaved ones and the Manchus as the demon devils. Such thinking was common in secret-society groupings such as the Heaven-and-Earth or Triad Society, with their mystical evocations of the fourteenth-century founder of the Ming dynasty, and their widely announced hopes of a Ming “restoration” that would overthrow the ruling Qing. Hong claimed not to accept all these myths, though his thoughts followed parallel tracks. He told his followers, “Though I never entered the Triad Society, I have often heard it said that their object is to subvert the Qing and restore the Ming dynasty. Such an expression was very proper in the time of Kangxi [ruled 1661–1722], when this society was at first formed, but now after the lapse of two hundred years, we may still speak of subverting the Qing, but we cannot properly speak of restoring the Ming. At all events, when our native mountains and rivers are recovered, a new dynasty must be established.”19

In an eight-line poem written in the year 1850, Hong Xiuquan invokes images from the great founders of the Han and Ming dynasties to underline his political mood of excitement and belatedness: Both these earlier dynastic founders were men from poor farming families who had risen by courage and tenacity to overthrow tyrannical rulers and found new dynasties that endured for centuries. Both were famous for fighting against alien conquerors or invaders. According to popular stories Liu Bang, while engaged in the bitter military campaigns that led ultimately to his establishment of the Han dynasty in 202 B.C., had been so exhilarated by the winds that sent clouds scudding above his head, likening their rapid motion to his own troops, and seeing an omen that his armies would carry all before them, that he laid out ritual wine on an extemporized altar to salute the wind’s passing. While Zhu Yuanzhang, who was forty years old by the time he overcame his numerous rivals and founded the Ming in 1368, liked to compare himself to the autumn-blooming chrysanthemum, which comes into its splendor only when the other apparently more vivid flowers have flourished and faded. As Hong wrote:

Now at last the murky mists begin to lift,

And we know that Heaven plans an age of heroes.

Those who brought low our sacred land shall not do so again;

All men should worship God, and we shall do so too.

The Ming founder tapped out the rhythm of his chrysanthemum poem,

And the Han emperor poured out wine for the singing wind.

As with all deeds performed by men since ancient times,

The dark clouds are scattered in reflected light.20

In February 1850 a change seems to occur in the shape of the God-worshipers’ military organization or at least in the language with which it is discussed. From this month on there is talk of the God-worshipers having an “army” on the march, moving between the four areas where they have their bases, an army that demands careful tactical planning, feeding, and other logistical support. There are set piece attacks on prepared “demon” positions. Loyal “troops” who have traveled from distant places have to be replaced, and allowed time to rest up, unless ten or twenty of them choose to volunteer for further combat. Troops from “nearby places” can stay in action for a few days longer. Reports of military action have to be carefully written up by the commanders and taken to Hong Xiuquan’s temporary home in the northeastern Pingshan base area, where Hong is recovering from a leg injury that prevents him from riding on horseback. Hong’s base area is now sometimes called “the court,” and Hong himself referred to as the “Taiping king.” Tempers flare at some of the leaders’ strategy meetings, as they argue about whether to press on with a given attack or to retreat. Food supplies run out, with no prior warning being given to commanders in the field, causing desperate hardship.21

A record of conflict from Baisha village, a few miles east of Hong’s temporary home of Sigu and just outside the southern area of God-worshipers’ control, shows many of these elements in place at once: the violence slowly growing, from squabble to threat to confrontation, with the concern over arms and supplies constantly cutting into the narrative. The enemy driving the people of Baisha into the God-worshipers ranks are first described as “demons,” and might be government-supported non-Hakka local families, or local bandit groups allied to such families. In the main part of the narrative, they are simply called “bandits,” or “outsider bandits.”

Heavenly Brother asked Luo Nengan about the real situation in Baisha. He answered, “Li Desheng left his plowing buffalo with Lin Fengxiang to be fed. The outsider bandits from Lingwei village tried to extort money from Li Desheng, but the latter refused. So two of the bandits stole Li’s buffalo from Lin Fengxiang’s, but Lin got it back from them. He did not hurt the bandits during the fight. Next day, forty or fifty bandits went to Lin’s house, yelling and trying to provoke a fight. Eight of us, while preparing our meal, saw the bandits begin to shoot their guns. Five of us grabbed our own weapons, and chased them; they escaped, leaving behind two cane shields, a box of gunpowder, and five guns. The second time, two hundred bandits showed up and we defeated them with fifty-eight people. They escaped and left three cane shields, a box of gunpowder, two guns, and one ‘cat-tail-shaped’ gun. Now we have assembled one hundred eighty brothers in Baisha.”

Heavenly Brother asked Luo Nengan how they could supply enough food for the army. Luo: “The relative of Li Deshang, Wu, donated two thousand dan of rice.”

Heavenly Brother: “Who arranged the horses?”

Luo: “Qin Rigang.”

After Heavenly Brother asked Luo many questions, He bid Luo to return and temporarily disband his troops, just retaining a dozen or so. Heavenly Brother: “When you go back, don’t worry! Everything will be taken care of by Heavenly Father’s and Heavenly Brother’s Heavenly Army. You can defeat one thousand people with ten people; if they dare come again, we will send more troops to fight them. . . ,”22

Given the colossal amount of grain these new Baisha allies could offer—two thousand dan would have been over one hundred tons—they would be invaluable allies in case of a major attack or siege by Qing forces. Yet the God-worshiping leaders were still clearly cautious about massing so many people in the central base areas that they would prompt immediate reprisals.

Inevitably the leaders of the God-worshipers worry about the potential loyalty of followers such as these: some call the new recruits “brothers,” some call them “demons.” Sometimes Jesus, through Xiao Chaogui, is asked for his opinion, and declares the newcomers good people, worthy recruits to the Taiping cause, people who will “support the kingdom.” Hong Xiuquan often remains unconvinced, believing that the true goal of these strangers from afar is to “destroy the army.”23

Regardless of such suspicions, there are mass baptisms of the new arrivals, four hundred at a time one day in late February 1850, after they have been preached to at some length, and taught the secret code names for their leaders. As to the hierarchy of the top leadership, as it is now emerging, the faithful are told that “those who sincerely acknowledge Hong Xiuquan are in the presence of the Old One on High; those who sincerely acknowledge Feng Yunshan, [Yang] Xiuqing, and [Xiao] Chaogui are in the presence of Old Elder Brother.” The converts are told to live with patience and sincerity, to convert their wives and children, so that all may live as children of God before their final entry into Paradise.24 For their part, the leaders undertake to receive all the sincerely faithful into the God-worshiping ranks, whether or not they bring “ritual offerings” with them, for all are equal before the Lord, and each family’s lacks or surpluses are the common concern of all.25 By early April 1850 Hong Xiuquan sometimes wears a yellow robe, a garment only emperors are allowed to assume, though he wears it in secret, inside the home of the believer with whom he is sheltering.26

The transcript of the initiation of one God-worshiper into the nascent Taiping forces has been preserved in a Taiping text. This particular ceremony takes place on April 9, 1850, at Hong Xiuquan’s base—or retreat—in Pingshan. (The convert, Tan Shuntian, later became one of the Heavenly King’s senior officers.) The main questions are posed by Xiao Chaogui, acting as mouthpiece for the Heavenly Elder Brother, Jesus. Hong Xiuquan is present, but acts as observer only, seated—in the absence of any other furniture in this isolated mountain home—upon the bed. The Taiping’s own record of this encounter runs as follows:

Heavenly Brother declared to Tan Shuntian: “Tan Shuntian, do you know who is talking to you now?”

Tan Shuntian: “You, Heavenly Brother.”

Heavenly Brother: “Who is that person sitting on the bed?”

Tan: “It is Second Brother [Hong Xiuquan].”

Heavenly Brother: “Who sent him here?”

Tan: “Heavenly Father.”

Heavenly Brother: “Why did Heavenly Father send him here?”

Tan: “Heavenly Father sent him to become the King of Great Peace [Taiping].”

Heavenly Brother: “What is meant by: ‘adding starlight brings the view of Holy Father’?”

Tan: “It means if we have our Second Brother [i.e., Hong Xiuquan], we will be able to see Heavenly Father.”

Heavenly Brother: “Who is ‘Rice King’?”

Tan: “It is Second Brother.”

Heavenly Brother: “You should acknowledge him. In Heaven you should trust Heavenly Father and me; on earth you should follow his instruction; you must not be stubborn and willful, but follow him obediently.”

Tan: “With all my heart I will follow Heavenly Father, Heavenly Brother, and Second Brother.”

Heavenly Brother: “Who is ‘Two Stars with Feet Up’?”

Tan: “It is East King [Yang Xiuqing].”

Heavenly Brother: “Who is ‘Henai’?”

Tan: “It is also East King.”

Heavenly Brother: “You should recognize East King since it is he who is the mouthpiece of Heavenly Father. All nations on earth should listen to him.”

Tan: “Yes, I know.”

Heavenly Brother: “Shuntian, at times of hardest testing do you lose your nerve or not?”

Tan: “I do not lose my nerve.”

Heavenly Brother: “You should remain faithful until the end. It is just as it is with sifting rice, one watches it with one’s eyes and then separates out the grains. The Taiping course is set, but caution is still essential. The basic plan must not be divulged to anyone.”

Tan: “I will obey the Heavenly Command.”

The next day, Tan received his formal baptism.27

As the troubled times draw more and more men and women to the God-worshipers’ ranks, the Taiping leaders must not only feed and protect the newcomers but also protect their own reputation for virtue, and stop both licentiousness and dissension in their own ranks. Hong’s original commandments had been strongly critical of sensuality, and now these are reinforced by examples from the Bible and Mosaic law. It is early in 1850 that the Taiping leaders begin to make pronouncements hinting that men and women should be separated, in the interests of decency and the common good. Feng Yunshan, Hong’s close friend and founder of the God-worshipers, who has left his wife and children at home in Guanlubu, is held up as the model for male behavior. A woman, Hu Jiumei—probably a daughter of the wealthy Hu family that had donated their possessions to the God-worshipers—is announced to be the paragon of female behavior. God Himself, through His son Jesus, sends poems down to earth in their honor, brief classical poems each of four seven-beat lines, that make mnemonic puns on the chosen models’ names, and point out their virtues. Thus the poem for Hu Jiumei as the paragon for women plays on the idea that the homophone for Hu’s name is another character that means “lake”:

Women observing Hu, a well of pure water,

Will long remember that pure repose as they boil up their tea.

The mountain birds can be large or small, the trees make no distinctions;

Each red flower has a single bud, dwelling among men.28

Speaking through one of the congregation, God’s wife also comes to earth, with her own exhortations to the God-worshipers: “My little ones, above all heed the instructions of God the Father. Next, heed the instructions of your Celestial Elder Brother. In general, be faithful and true, and never let your hearts rebel.”29

Such moral exhortations are backed by stern examples of public punishment for wrongdoers. One God-worshiper named Huang Hanjing, who is discovered to have been having sexual relations with a woman, is condemned to a beating of 140 blows with a heavy pole. The woman he slept with—even though Huang had either kidnapped or abducted her in some way—receives 100 blows.30 Given the shock and loss of blood from such beatings, this number of blows could amount to a death sentence.

The webs of divine and earthly family relationships inevitably intertwine in these heavenly messages and practical instructions. When Xiao Chaogui, for example, spoke as the voice of Jesus, he would naturally address Hong Xiuquan as his “younger brother.” But in earthly life, Xiao had recently married a female relative of Hong Xiuquan’s, perhaps a cousin, and so the two men were bonded together as “brothers-in-law.” If Xiao wished his wife to be more obedient, as he apparently did at times, then he could do so in the voice of Jesus demanding that his “blood relation” obey her husband.31 Instructions from on high, parallel to those given to Hu Jiumei, could also be given in the name of God or Jesus to other God-worshiping women prominent in the organization, as in the case of those for the “second daughter” of the Chen family, Chen Ermei. Such messages had the force of divine decrees, as in the case of the one of January 30, 1850: “Chen Ermei, women must know how to keep out of the way: men have quarters that should be left to men, and women have quarters that should be left to women. Senior or junior sisters-in-law should also keep a proper balance, for the older ones have things to do that would not be suitable for younger sisters-in-law, just as the younger have things to do not suitable for the older. It is never good for them to compete with each other.”32

From such pronouncements grows the Taiping policy of separating men and women altogether into separate camps and units, until such time as all will win their Heavenly Kingdom and be reunited. But as the Taiping develop this policy it results not merely in restricting women’s lives but also in the formation of women’s army units, and in establishing the rights of women to serve as officials in the Taiping bureaucracy. The fullest explanation of this policy’s rationale from a Taiping text is the following:

Moreover, as it is advisable to avoid suspicion [of improper conduct] between the inner [female] and the outer [male] and to distinguish between male and female, so men must have male quarters and women must have female quarters; only thus can we be dignified and avoid confusion. There must be no common mixing of the male and female groups, which would cause debauchery and violation of Heaven’s commandments. Although to pay respects to parents and to visit wives and children occasionally are in keeping with human nature and not prohibited, yet it is only proper to converse before the door, stand a few steps apart, and speak in a loud voice; one must not enter the sisters’ camp or permit the mixing of men and women. Only thus, by complying with rules and commands, can we become sons and daughters of Heaven.33

Hong Xiuquan gradually came to apply the idea of the separation of the sexes not only to unmarried men and women joining the Taiping but even to husbands and wives within the Taiping ranks. Such a doctrine, if rigorously enforced, would obviously make procreation impossible until the Taiping created their projected Heavenly Kingdom. This would have advantages for a large army, with many civilians, on the march, but it would be the final blow to any lingering adherence to Confucian views of filial piety toward ancestors with their emphasis on production of a male heir. Hong Xiuquan himself might well have been rendered more receptive to a policy of separation by gender by the news he received in January 1850—rushed to him from Guanlubu—that his wife, Lai, whom he had left at home pregnant when he returned to Thistle Mountain, had given birth to a boy, on November 23, 1849, and that both mother and son were strong and well.34 Hong names the boy Tiangui, “Heaven’s Precious One.”

For five months after receiving this news Hong appears absorbed with the world of God-worshipers, and seems to have no special concern over his family. Then, in the middle of June 1850, despite the perils of the journey, he suddenly summons them to join him in Thistle Mountain. Hong does not go in person to Guanlubu, but sends a small delegation of three trusted followers he has known since his earliest visits to Guangxi. One of these men is a physician, who carries always his box of medicines with him as he travels, to quell the suspicions of any government patrols they might encounter.35 These three men carry a letter to his family, and though we do not have the letter, we know the effects are immediate. Within days, most of Hong’s close family members have packed up or disposed of their possessions, and begun the long trip from Guanlubu to the Thistle Mountain base area. Given the advanced age of some members of the group, and the fact that Hong’s baby son is still less than eight months old, it is probable that they travel by boat or by litter. (The adults in Feng Yunshan’s family choose not to leave their homes, though they do send Feng’s two sons to join their father and the God-worshipers.)36

What prompts Hong to this decisive action at this particular time is not completely clear. A number of factors may have flowed together in his mind. For one, the kidnapping of God-worshipers’ children for ransom was becoming a nightmarish part of life, and Hong may have feared for his family’s survival if they stayed in Guangdong.37 Also there were famine conditions in parts of Guangdong province, including the region around Hong’s original home district of Hua. Furthermore, Hong has developed an apocalyptic view of the fate of mankind, claiming that God told Hong that in the thirtieth year of Emperor Daoguang’s reign (equivalent to the Western 1850), He would “send down calamities; those of you who remain steadfast in faith, shall be saved, but the unbelievers shall be visited by pestilence. After the eighth month, fields will be left uncultivated, and houses without inhabitants; therefore call thou thy own family and relatives hither.”38

In addition, in May 1850, Yang Xiuqing, the spokesman through whom God’s messages had for more than a year been relayed to the God-worshiping faithful, and who had been claiming to cure the sicknesses of all true believers by absorbing their sicknesses into his own body, himself fell ill with a mysterious yet shocking malady: he “became deaf and dumb, pus pouring out of his ears and water flowing from his eyes; his suffering was extreme.”39 Taiping sources later said this illness had two causes: Yang’s “weariness” from redeeming his followers from harm, and God’s determination “to test the hearts of us brothers and sisters.” But at the same time, those not aware of these twin causes considered that Yang had “become completely debilitated by illness.” If Yang had in some ways been constricting Hong Xiuquan’s freedom of action, as many both then and later believed, his spell was now temporarily broken, and Yang remained in his “debilitated” state until early September 1850, when he suddenly recovered.40

Xiao Chaogui, too, almost ceased to speak in the name of Jesus during the whole spring and summer of 1850. Later that summer Xiao was described as being afflicted by some kind of ulcers or running sores, which cut back his activities, and perhaps this painful scourge had already caught him. Conceivably, also, he was chastened by Yang’s illness and God’s silence, and preferred not to speak if Yang could or would not.41 Compared with the flood of celestial edicts earlier and later in the year, there were only two messages from Jesus during this period, both brief: on May 15, when Hong Xiuquan nervously asked him, “What is the demon devil Yan Luo doing at this time?” Jesus replied, “He has been cast down and bound, and is powerless to cause trouble. Let your heart be at ease, let your heart be at ease.”42 And on June 2 Jesus urged Hong, along with key supporters, to stay out of sight “while the demons killed each other. Once they are completely exhausted, then of course the Heavenly Father and Heavenly Elder Brother [Jesus] will give you clear orders on what to do next.”43 This elliptical statement may well refer to the massive campaigns of bandit suppression that Qing government forces were finally initiating around the Guiping area, campaigns that would bring both opportunities and fresh dangers to the God-worshipers.

It is July 28, 1850, in the afternoon, when Hong Xiuquan and his family are reunited, at a little village in Guiping district. There is Hong’s wife, Lai, their two daughters, and their baby son, whom Hong now sees for the first time. There is Hong’s recently widowed stepmother. Hong’s elder brother Hong Renda and Renda’s wife and family have obeyed the summons, as has Hong’s wife’s uncle. Hong’s eldest brother and wife, and other cousins and children, are on the way. The family is further increased by various male members of the Lai family who live near Guiping. Since Hong’s wife is a Lai, they now claim relationships as Hong’s “brothers-in-law,” claims that Hong accepts.44 Accompanying the group of relatives are three more of Hong’s most trusted friends, two men and one woman: Qin Rigang, a Guiping native and sometime soldier and miner; Chen Chengyong, a wealthy landlord from a nearby town who has brought his whole family into the God-worshipers’ camp; and one of the daughters from the same Huang family who had helped Hong so often.45 It is this woman—perhaps initially assigned by Hong to watch over his women family members as they traveled—who has offered up the Huang family residences to the large and disparate group. Asked if she and her family can afford to support so many people—despite the numerous brothers and sisters of the God-worshipers they have aided in the past—she answers, Yes, with the Lord’s help, and that of his son Jesus, they can.46

Xiao Chaogui, silent for months, now resumes his mediator’s role, and with the voice of Jesus summons the new arrivals individually to their duties as God-worshipers and protectors of their relative the Heavenly King. Hong’s elder brother, Hong Renda, is told to be cautious over whom he trusts, and not to let people scare him. He and his brother will fight for the rivers and mountains of China together; as one enters his Heavenly Kingdom, so will the other; as one gets food or clothing or the tribute offerings of the myriad nations on the earth, so will the other, as each partakes of their glory under God on High.47 Hong’s stepmother, Li, is told to instruct and watch over her daughter-in-law and the children, and to maintain their integrity, till she comes at last “to dwell in her golden palace built of golden bricks.”48 Hong’s eldest daughter, now a little over twelve years old, is told to trust in the teachings of her grand-mother, mother, earthly uncles, and her uncle Jesus. The other in-laws receive their suitable instructions. And to Hong Xiuquan’s own wife, Lai, come special words, in light of the special tasks confronting her: “Lai, with all your heart obey the Heavenly Commandments, and strive to bring honor to your husband, and preserve his reputation. Your husband is not as other men, so rejoice at your good fortune, cleave to this your husband; you are not as other women, you must discipline yourself with extra vigor, be filial to your parents, and obedient to your husband. Leave the education of your children to your older sister-in-law. It is no light task to be the wife of the Taiping Lord of all the countries on this earth.”49

For a month the Hong family live together near Guiping township, sheltered by the Huangs, but it is a dangerous and fugitive existence, with the possibilities of arrest or betrayal at every turn. As anxiety mounts for the group’s safety, Wei Changhui, whose own wealthy clan have made the market town of Jintian a safe haven for the God-worshipers, negotiates and plans with other leaders to bring the group northwards. This is no mere matter of assembling a small group at night and proceeding on mountain tracks with covered lanterns. There are numerous sedan chairs to be hired, boats to be found, supplied, and placed at the right spot on the riverbank, away from prying eyes. There are elaborate stories to be made up, and rehearsed, so that if they meet Qing patrols all in the party can state with conviction where they have come from and whither they are going. Stupid mistakes are made, which nearly wreck the venture, and the Heavenly King loses his temper and has to apologize. But by August 28, 1850, they have crossed the broad river near Guiping and reached the Jintian base area, ready as a family to build the Heavenly Kingdom.50