There is no precise moment at which we can say the Taiping move from tension with the Qing state to open confrontation, but clearly in 1850 their provocations mount steadily until war becomes inevitable. It is in February 1850 that Hong and his closest associates begin to use martial language when talking of their followers. In April of that year Hong dons a robe of imperial yellow. In late July, Jesus tells Hong to “fight for Heaven,” “to take responsibility for all the rivers and mountains,” to “show the world the true laws of God the Father and the Heavenly Elder Brother,” and to realize God has given him “full authority” to rule his kingdom. “In such a venture,” says Jesus, “you must take the long view, not just focus on what is in front of you.”1 By August and September, the various Taiping leaders are beginning to assemble and arm groups of troops, and move them to the Jintian area.2 In mid-October, arrangements are made to keep beacons and signal lights burning through the night around Hong Xiuquan’s base area, so that the alarm can be instantly given in case of enemy attack.3 On October 29 Hong sends out a more general mobilization order, telling all his followers to prepare for action, though still he urges secrecy upon them. While it would be premature “to proclaim Hong Xiuquan openly as leader, or to unfurl the banners,” the God-worshiping brothers are told to begin to draw up plans, with those in the base area strengthening their defenses, while those in the outer areas not only make military preparations but “buy up gunpowder in bulk. When the general call goes out, then will be the time for all forces to unite.”4

The “bulk buying” of gunpowder would surely be a provocation, for such purchases might well be noticed and reported to the authorities, given the God-worshipers’ enemies among non-Hakkas and the local gentry. But this is seen as a calculated risk, a decision to end the period of surreptitious arms manufacture that has been going on for some months, especially in the Jintian village area, in which families like the Weis have set up front operations where simple arms are made by night, wrapped, and hidden in one of the myriad ponds that speckle the area.5 And though there is no separate Taiping banner to unfurl as yet, the rudiments of a system of signal flags for different military units have already been designed by Feng Yunshan and one of his friends.

Feng’s fundamental strategy is to build up units from the lowest levels systematically, and to identify each by clear markings and banners. Thus 4 men are to be under a corporal; 5 corporals and their men, a total of 25, are to be under a sergeant, who has his own square identifying flag, two and a half feet high. Four sergeants with their troops, 104 in all, are commanded by a lieutenant, with his own somewhat larger banner, and so by gradations up through captains and colonels to generals, who at full strength would have divisions of 13,155 troops under their command.6 Individual units are also to be identified by different-colored triangular flags, labeled with their base area in bold characters. In addition, the corporals have insignia, five inches square, on the back and front of their shirts or coats, identifying them by platoon and battalion, while privates have four-inch-square insignia, which give their squad and platoon of affiliation and their personal identifying codes. In every squad, to help standardize battle orders, the same four code names are given to the four soldiers, one being given the name “Attacking,” one “Conquering,” one “Victorious,” and one “Triumphant.” Signals for emergency use when flags cannot be seen at night are made by sound, using gongs and rattles, in an ingenious series of combinations, to differentiate each large unit from every other.7

Some of this organization, particularly the arrangement of the men in small-sized units with a clearly identified chain of command, is taken by Feng from the Zhouli, or “Rites of Zhou,” a text with a complex history of composition and transmission, allegedly detailing the administrative and military structures of the duke of Zhou, the efficient and moral minister of one of China’s earliest dynasties, who was deeply admired by Confucius. Feng even uses exactly the same terms for his units and their commanders as those in the Zhouli, and almost the same number of soldiers in each unit—the only discrepancy probably reflecting an ambiguity in the original text.8

Other commanders of local God-worshiping forces find these classical echoes either unnecessary, or pedantic, and an irritation with textual punctiliousness is clearly expressed by both Xiao and Yang, ascribing their views, as customary, to Jesus and to God. The two men’s sparring for prestige is obvious at times, expressed in their complaints that each is being forced by the other to “lose face” in public, since as Xiao says of Yang “men need to keep face just as trees need their bark.”9 Some Taiping leaders speak up for the need for scholarship and knowledge, branding Xiao and Yang as “hardly literate”; but Xiao and his friends in turn mock the misplaced “scholarship” of those who seem to prefer “antiquated texts on astronomy and geography” or classical poetry to the practical experience and useful knowledge of men who have “an unusually good understanding of things.”10

In preparation for potential conflict, units of God-worshiping troops are now assembling under their various commanders on a regular basis, and reciting aloud the entire Ten Commandments as they are listed in the Bible, with glosses and expansive commentaries provided by Hong Xiuquan himself. Even if the God-worshipers recite the commandments correctly, they can be publicly beaten for violating their basic premises, or for showing sarcasm or ignorance of God’s wider purpose.11 The Ten Commandments themselves become the basis both for daily life and for future hope, as Hong Xiuquan explains in a poem to his followers, and its accompanying commentary:

In your daily life, never harbor covetous desires;

To get caught in the sea of lust leads to the deepest grief.

In front of Mount Sinai the injunctions were handed down,

And those Heavenly Commandments, earnest and sincere, are full of power today.

Repent and believe in our Heavenly Father, the Great God, and you will in the end obtain happiness; rebel and resist our Heavenly Father, the Great God, and you will surely weep for it. Those who obey the Heavenly Commandments and worship the True God, when their span is ended, will have an easy ascent to Heaven.

Those who are mired in the world’s customs and believe in the demons, when they come to their end, will find it hard to escape from hell. Those sunk in their beliefs in false spirits will thereby become the soldier-slaves of false spirits; in life they involve themselves in the devil’s meshes and in death they will be taken in the devil’s clutches.

Those who ascend to Heaven and worship God, they are God’s sons and daughters; when they first came to earth, they descended there from Heaven.12

The public recitations of the commandments are a part of the constant probing by the God-worshiping leaders, a probing made urgent by the swiftly rising number of new recruits to their ranks. In late 1850, this influx becomes almost unmanageable, as two human movements numbering thousands of people converge on the Jintian base area. One of these is made up of Hakkas from four different neighboring areas, driven—like their brethren of Baisha—to seek shelter in the main base area because of the ever-rising local levels of violence directed against them by local non-Hakkas, by local gentry and officials, and by bandits of various kinds. Ironically, the last of these categories forms the second human wave—bandit groups themselves, no fewer than eight according to accounts at the time, who converge on the Jintian region because of the massive campaign now being coordinated against them by the Qing government.13 At least two of these bandit groups are led by women, and one by Big-head Yang, the Macao mixed-blood pirate who was central in causing the disruptions in Guangxi that gave such impetus to the growth of the God-worshipers in the middle 1840s.14

In early December 1850, regular units of the Qing forces, working with local gentry-led militia, and coordinated by their commanding officer in Guiping township, begin aggressive campaigning in the northeastern-most of the four God-worshiping base areas, the safe haven provided for Hong and his family by the Hus in Huazhou village. The Qing have not yet identified Hong Xiuquan as the God-worshipers’ leader, and they are acting on vague information that troublemakers are there. Nevertheless, they come dangerously close to capturing him. Crossing the broad river that flows past Guiping, the government troops bypass Jintian and converge on Huazhou from the south, via the village of Siwang. The terrain is treacherous, and the approach difficult—one narrow mountain track, with steep ravines to one side, sheer mountain walls to the other, a perfect place for ambushes. So while making a show of strength, the Qing troops content themselves with closing off the village by driving hundreds of sharpened bamboo stakes at an angle into the track and the adjacent slopes, making egress impossible. Alerted to the danger, Hong sends loyal messengers out by mountain tracks to the northwest, who then circle back to Jintian and warn the other Taiping leaders. Moving with dispatch, the God-worshipers attack the Qing forces from the rear, routing them, removing the stakes, and bringing Hong and his family safely back to Jintian. In the conflict there is heavy hand-to-hand fighting, and as many as fifty government troops and militia are killed, among them a deputy police magistrate, Zhang Yong. In the name of their God, the Taiping have now killed a “demon” who officially represents the ruling regime.15

Jintian village is crowded and in chaos from the masses of Hakka refugees, bandit recruits, local God-worshipers, and fresh recruits recently arrived. There are so many new arrivals that—despite the stock-piled grain resources of groups like the God-worshipers from Baisha—by early December conditions in Jintian have reached near famine levels, and the God-worshipers and their allies are reduced to a daily ration of thin rice gruel. Some of the bandit troops defect in the face of this hardship, while the Taiping leaders try to keep morale high among their own troops by pointing out that this deprivation is a simple trial, devised by God and His son Jesus, “to test the determination” of their followers on earth.16

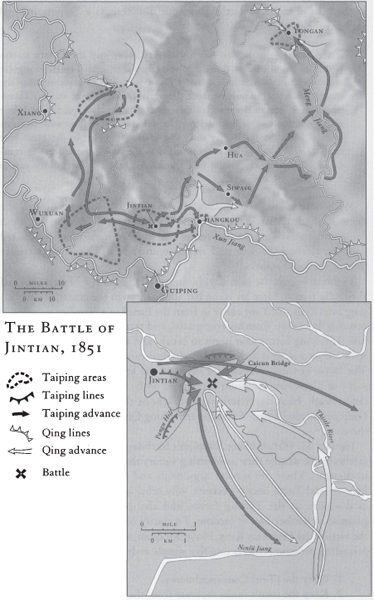

It is no surprise, after the killing of one of their officers in the line of duty, that the Qing attempt a second strike, this time more thorough and more massive. On December 31, 1850, a much larger Qing force, commanded by a dozen veteran officers and supplemented by some local militia, which has marched northeast from Guiping in three columns, crosses a tributary of the Xun River and establishes a base area command post only five miles from the village of Jintian. The Taiping forces, now with their recent recruits and bandit allies at least ten thousand strong, march a mile east of Jintian and take up three coordinated defensive positions in a wide arc between the Qing forces and Jintian, with Yang Xiuqing commanding the troops on the left flank, extending to the point where Caicun Bridge spans the Thistle River; Xiao Chaogui on the right flank, centered on Pangu Hill; and Hong Xiuquan and Feng Yunshan commanding the center.17

The complicated defensive formation adopted by the Taiping troops shows they are confident in their battle readiness and in the communications system they have devised. Each major Taiping encampment has its own signal flag, depending on its strategic location: red for the south, black for the north, blue for the east, and white for the west. The center has a yellow banner, as well as a duplicate of the other four banners. With these large flags as the main signals, backed by smaller triangular flags to request troop reinforcements, complex instructions can be conveyed even in the heat of battle, and at considerable distance. As a Taiping manual explains the system:

If the demons on the east side prove very active and the eastern station wishes to draw soldiers from the west, they shall add a small triangular white flag to the great blue banner. This signal shall be transmitted to the center which will in turn transmit the signal to the western station. Thereupon the officers in command of the western station shall quickly lead their soldiers to the east to help destroy the demons. Or if they wish to draw soldiers from the south they shall add a small red flag to the great blue banner. When this signal is transmitted to the south, the officers in command of the southern station shall quickly lead their soldiers to the east to help destroy the demons.18

With only minor adjustments, this same system can be used if the demons attack on two fronts at once. For instance, if the east and south come under attack at once, the center will hoist both the blue and the red banners, alerting the west and north commanders to prepare to relieve their embattled brothers.19

Fighting begins the next day, January 1, 1851. As the Manchu colonel Ikedanbu tries to force his seven battalions through the center of the Taiping line, Xiao and Yang curve in from the flanks in a coordinated assault, severing Ikedanbu from his rear guard, and trapping him against a small hill. The Qing forces soon begin to break, and the break becomes a rout, with a dozen officers and three hundred or more dead on the Qing side. The horse of Colonel Ikedanbu skids on the bridge as its rider flees the scene of his defeat. Ikedanbu is pounced on by Taiping foot soldiers and cut to death. Next day, reinforcements sent by the commanding officer in Guiping are also defeated, and the remaining Qing troops pull back across the river.20

January 11, 1851, is Hong Xiuquan’s birthday, but there is little time to celebrate, for despite their astonishing victory the Taiping forces are again in disarray. There are massive arguments and quarrels with the various Heaven-and-Earth Society recruits, who rebel against the excessive levels of discipline in the Taiping forces, and also perhaps at the absence of promise of further loot or income. To clarify his own position, just after the victory the Heavenly King, Hong Xiuquan, summarizes all his various preceding pronouncements into five simple orders:

1. Obey the [Ten] Commandments.

2. Keep the men’s ranks separate from the women’s ranks.

3. Do not disobey even the smallest regulation.

4. Act in the interests of all and in harmony; all of you obey the restraints imposed by your leaders.

5. Unite your wills and combine your strengths and never flee the field of combat.21

With resources dwindling, and with the disturbing news that Big-head Yang, the woman leader Qiu Erh, and several other secret-society leaders have not only abandoned the Taiping camp but offered their services to the Qing forces in exchange for official positions and pardons, Hong and his fellow leaders decide to abandon Jintian, and move to a base with better defensive possibilities. Their choice falls on the prosperous market town of Jiangkou, fifteen miles to the east, on a fork of land where two rivers converge, making it a good base both for controlling commerce and for supplying reinforcements. Since Jiangkou is also the chosen base for Big-head Yang’s renegade forces, as well as the hometown of Wang Zuoxin, the gentry and militia leader who so often crossed and harried the God-worshipers in the past, the town offers a nice focus for revenge. By mid-January the Taiping have left Jintian, ahead of any counterattacking Qing forces, and by the end of the month they have taken over Jiangkou and refurbished their forces. They are crucially aided in this endeavor by the one major Heaven-and-Earth leader who has not defected, the sincere God-worshiper Luo Dagang; from this time onward Luo becomes one of Hong’s key advisers, bringing the Taiping crucial skills in the command and execution of water-borne campaigning, navigation, and supply.22

But Jiangkou is too well chosen for the Qing to allow the Taiping to keep it as their base. This time, learning from past defeats, the newly appointed coordinating general for all Guangxi forces, Xiang Rong, with two other generals commanding troops from Yunnan and Guizhou, leads three massive columns of troops by land to Jiangkou, supported by two water-borne columns—some ten thousand troops in all. By mid-February they have reached the Jiangkou area. For three weeks the Taiping hold the town, but the forces against them prove too strong, and in early March the Taiping leaders slip out of the city at night and head back to their original base areas near Guiping, settling in the area of Wuxuan township, west of Guiping. During their retreat, the city of Jiangkou is burned to the ground, each side blaming the other for the disaster.23 For the rest of the spring of 1851 the fighting is bitter in the region, if sporadic.

It is in the midst of this chaotic period, perhaps in March 1851, that Hong Xiuquan declares the formal existence of the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom, a concept long promised yet long delayed. Oddly, however, there is no single ceremony, not even any single day, to point to, and the Taiping themselves never celebrate any particular anniversary for their founding. An unexplained illness of Hong Xiuquan in the spring—described in one Taiping source as the “pestilence”—may have further delayed the dates of key decisions on organization. But from this springtime on, the year known in the West as 1851, and to the Qing dynasty as the first year of the Emperor Xianfeng, is called by the Taiping themselves the First Year of the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom.24

Starting from March 30, 1851, a new kind of public ritual is inaugurated, one that combines celestial advice on the kingdom, rewards for the virtuous, and stern punishments for the backsliders. On this day, Jesus (through Xiao) talks of the growing strength and complexity of the Heavenly Kingdom now on earth, and his special desire “to discipline those who disobey the Heavenly Commandments.” After this introduction, Jesus gives voice to a fuller exposition of confidence in the Taiping kingdom’s future:

All of you should be at ease and try your hardest. When undertaking this Heavenly enterprise, you cannot take all the weight on your own head. This enterprise is directed by Heaven, not by men; it is too difficult to be handled by men alone. Trust completely in your Heavenly Father and Heavenly Brother; they will take charge of everything, so you need not worry or be nervous. In the past I tried to save as many mortals as possible from among those who were threatened with destruction by demons. Now we have so many followers of God, what should you fear? Those who betray God won’t be able to escape Heavenly Father’s and Heavenly Brother’s punishment. If we wish to have you live, you will live; if we want you to perish, you will die, for no one’s punishment will be postponed more than three days. Every one of you should sincerely follow the path of Truth, and train yourselves in goodness, which will lead to happiness.25

Following this statement Jesus gives his blessings to a long list of Taiping leaders and staff officers—some twenty-three in all—who are taken to Heaven and initiated into its mysteries. Jesus then gives specific instructions to the five military leaders, identified by their army corps: front, left, rear, right, and wing—in other words, to Hong’s five associates Yang, Feng, Xiao, Wei, and Shi. They are told that disobeying a military order is the same as disobeying the word of God, of Jesus, or of the Heavenly King, Hong Xiuquan. To underline this sense of discipline, an opium smoker in the Taiping ranks is publicly tried—“Can you fill your stomach by smoking opium?”—savagely beaten (with “one thousand blows” according to the text), and then given a last meal of glutinous rice before being publicly executed. Another battalion commander is given one hundred blows for not being watchful for traitors within his own unit, and Jesus then gives each commander authority to “kill any such rebels before reporting them to higher authorities, since killing these rebels won’t lessen the strength of our armies, whereas having rebels in our army ranks harms the entire kingdom.” No units, Jesus emphasizes, are free from such traitors, so eternal vigilance is needed.26

A brief reminder to all the faithful of Hong Xiuquan’s kingship, and of the awe due to him as the ruler of the world sent down by God, is given by God Himself, speaking through Yang Xiuqing, on April 15, 1851.27 Then, on April 19, while the Taiping troops are still fighting for survival in the same area of Wuxuan, another solemn meeting is held, containing the same general elements as that of March 30 though in different order: a public trial of a wrongdoer followed by mass expressions of devotions and religious commitment and a general pronouncement on policy. This time, the wrongdoer is a man who has abused his trust as the bodyguard to the family of the Triad leader and pirate-turned-Taiping general, Luo Dagang, by stealing a golden ring and a set of silver toothpicks from Luo’s wife while she was in a religious trance.28 Like his opium-smoking predecessor the previous month, the thief is to be given one thousand blows, prior to receiving his final meal of glutinous rice and being consigned to the executioner’s sword and “a life in hell.” The solemn ceremony this time is for all the unit commanders, at the army, divisional, and battalion levels. Jesus’ words on this occasion are not only remembered; they are made a written part of one of the Taiping movement’s most sacred texts:

All of you, my younger brothers, must keep the Heavenly Commandments and obey military orders; you must be harmonious with your brothers. If the leader has more to do than he can manage, let his subordinates assume some of the duties; if the subordinates cannot carry out their duties, then let their superiors take on some of them. You must absolutely not consider people as enemies and hate them because of some chance sentence they uttered that you then committed to memory. You should cultivate goodness and discipline yourselves. When you are in a village you must not ransack people and their possessions. In combat you must never flee from the field when going into battle. If you have money, you must recognize that it is not an end in itself, and not consider it as belonging to “you” or “me.” Moreover, you must, with united heart and united strength, together conquer the hills and rivers. You must clearly discern the road to Heaven and walk upon it. At present there is some hardship and distress; yet later you will naturally be given high titles. If, after receiving these instructions, there are any of you who still violate the Heavenly Commandments, still disobey military orders, still willfully contradict your superiors, and still, when advancing into battle, flee from the field, you should not blame me, the Heavenly Elder Brother, if I give orders for your execution.29

From this time on, also, as a heightened proof of the religious discipline now to be expected, those who fail to attend meetings when summoned, or even those who are late, or stumble in their responses to the religious ritual questions, can be beaten with one hundred blows, dismissed from their military posts, or both.30

The frustrating, circular fighting over all-too-familiar ground continues through the spring and summer heat of 1851. The most important of the battles is one the Taiping fail to win. Seventy miles to their south, on April 19—the same day as the major Taiping trial and rally—God-worshipers from a fifth base area have crossed the border from Guangdong province and managed to seize the town of Yulin. The leader of these God-worshipers, Ling Shiba, a Guangdong native, is known to the Heavenly King. Ling had been converted to the God-worshipers’ religion while laboring as a migrant indigo gatherer in the Pingshan Mountain area, between 1848 and 1849, and became a passionate believer. Moving between his Guangdong native place in Yixin township and the Thistle Mountain base area, Ling converted hundreds to the cause, and prospered in business. Early in 1850 he sold all his accumulated land—paddy field, unirrigated land, and mountain land—and put all the proceeds, more than 340 ounces of silver, into the common Taiping treasury.

Even earlier than other leaders in Thistle Mountain, Ling began secretly to make and stockpile arms, store gunpowder, and prepare red cloth and sashes for his fledgling army. But when he approached Hong Xiuquan in the summer of 1850, asking to join him in Jintian, he was told to wait for a more propitious time. While waiting, he built up his military base by holding off the local militia, and roused popular support by seizing granaries and opening them to the poor, and by posting placards in villages attacking the greed and selfishness of local landlords and officials. Now, in mid-1851, with three thousand or more of Ling’s troops holding Yulin and ready to move north to join up with Hong, the times are propitious indeed. But realizing the fateful nature of this planned union of Taiping forces, the Qing generals concentrate all their resources to stop Ling from moving north, and to stop Hong’s troops from moving south. Despite repeated attacks on the Qing lines, neither army of the God-worshipers can break through.31

The key figure in preventing the linkup between Hong Xiuquan’s troops and Ling’s is the same former pirate leader Big-head Yang, whose riverine forces prevent all Hong’s attempts to cross the Qian River. And by June 1851 the incessant counterattacks of the Qing and local militia troops force Ling to abandon Yulin, and to retreat back eastward into Guangdong. To strengthen their morale after this setback, Hong’s Taiping troops are told in mid-June to shed their doubts and fears, and not only to protect their “kingdom” as it is now constituted, or to look to eternal rewards in Paradise at God’s right hand, but to fix their sights on the coming “Earthly Paradise,” or “Heaven on earth” (xiao tian tang), where all God-worshipers “would receive rewards beyond their expectations.” Though the exact location of this yearned-for place is not disclosed, this is the first indication Hong Xiuquan has given that the Taiping forces may soon have a permanent base in which they and their families can live in joy and peace.32

The Qing forces keep up their pressures throughout the Taiping base area, and despite these promises of an Earthly Paradise Taiping morale begins to sag. Taiping leaders single out for praise the women’s units, which with some divine help repulse formidable militia attacks.33 But instructions issued to unit commanders at the newly instituted roll calls for soldiers suggest that attrition is taking its toll: a name board is now to be prepared for each unit, with the names of soldiers assigned to the unit written on it. Those who have “ascended to Heaven” since the fighting began—that is, have died in combat—have their names marked with a red dot; those who are ill are marked with a red circle; those wounded are marked with a red triangle; and those who have recently deserted are marked with a red cross. “Thus,” says the Taiping instruction, “the person who calls the roll, upon reading the name board, will know immediately the number of available soldiers.”34 In his constant hunts for traitors in the Taiping ranks Hong—aided at times by timely warnings from Jesus relayed to earth by Xiao Chaogui—orders public executions for those caught, and placards hung around their necks, reminding all that “Jesus our Elder Brother showed us the treacherous heart of this demon follower.”35

By mid-August 1851 Hong and the other Taiping leaders have come to a difficult decision. Despite the hallowed role of Thistle Mountain in their movement’s founding and growth, they must make a breakout. To do this successfully calls for extraordinary secrecy and meticulous planning. Special orders are given forbidding any record of the discussions about the decision; even so, there is obviously bitter disagreement, and many God-worshipers are castigated for their selfishness and pettiness as the time for departure approaches.36 It is Hong Xiuquan who has to explain this collective decision to his followers, and he does so in both celestial and strategic terms:

In the various armies and the various battalions, let all soldiers and officers pluck up their courage, be joyful and exultant, and together uphold the principles of the Heavenly Father and the Heavenly Elder Brother. You need never be fearful, for all things are determined by our Heavenly Father and Heavenly Elder Brother, and all hardships are intended by our Heavenly Father and Heavenly Elder Brother to be trials for our minds. Let every one be true, firm, and patient at heart; and let all cleave to our Heavenly Father and our Heavenly Elder Brother. The Heavenly Father previously made a statement, saying, “The colder the weather, the more clothing one can remove; for if one is firm and patient, one never notices such things.” Thus, let all officers and soldiers awake. Now, according to a memorial, there is at present no salt; it is then correct to move the camp. Further, according to the memorial, there are many sick and wounded. Increase your efforts to protect and care for them. Should you fail to preserve a single one among our brothers and sisters, you will disgrace our Heavenly Father and Heavenly Elder Brother. . . .

Whenever the units advance or pitch their tents, every army and battalion should be equally spaced and in communication, so that the head and tail will correspond. Use all your strength in protecting and caring for the old and the young, male and female, the sick and the wounded; everyone must be protected, so that we may all together gaze on the majestic view of the Earthly Paradise.37

Once again, there is no sign of where the Earthly Paradise lies. But there are indications of its general direction, since the breakout is made to the northeast. In military terms, the maneuver is stunningly successful: fast, disciplined, coordinated, and leaving the Qing troops off-balance. But it is ruthless too, for the masses of the God-worshipers are told to burn their houses as they prepare to leave, as proof of their total commitment to the Taiping cause. And as each village is abandoned, it and the surrounding hills are combed for hidden supplies of food that will be needed on the march.38 The vanguard land forces of the Taiping are led by Xiao Chaogui and Shi Dakai, and the river forces by Luo Dagang; they move swiftly up the Meng River valley toward the walled city of Yongan, some sixty miles north-northeast of Thistle Mountain. Unable to work out what route the Taiping are taking, two pursuing columns of Qing troops move either too far to the west or too far to the east to stop them. Hong Xiuquan, guarded by Yang Xiuqing’s central army, moves behind the vanguard by river, with his family. Feng Yunshan and Wei Changhui are given the dangerous task of guarding the rear of the massive column.

The city of Yongan, though stoutly walled, is unprepared for such an onslaught, and not strongly defended. The Taiping vanguard forces reach the edges of Yongan on September 24, 1851, and in a strategy later lauded in Taiping accounts, they bewilder and shatter the nerves of the city’s defenders by riding their few horses around the city walls with baskets of rattling stones to amplify their sound and exaggerate their numbers, and by lighting and hurling into the city, throughout the night, a large store of fireworks that they have found in the suburbs. The next day, with the city’s residents dazed and sleepless from the explosions, fumes, and colored lights, the Taiping forces train what cannon they have on the city’s east gate, and send scaling parties over the walls—some protected from the defenders’ fire by coffins held on long poles over their heads, others laying ladders horizontally onto the walls from the roofs of nearby houses that the defenders have failed to demolish. By evening, eight hundred Qing troops are dead, and their senior officers have been killed or have committed suicide. It is September 25, 1851, and fourteen years after Hong’s first celestial battle the Taiping have acquired a solid earthly city.39