The Earthly Paradise is not just one place. It is the whole of China, wherever the Taiping Heavenly Army can reach the people and destroy the demons, so that all may live together in perpetual joy, until at last they are raised to Heaven to greet their Father.

Hong Xiuquan, the Heavenly King, and Yang, the East King, and other leaders have developed the military ideas of Feng Yunshan and combined them with their experiences at Thistle Mountain, Yongan, and Wuchang, to create their own ideal system. Just as in the Taiping armies there are four private soldiers under every corporal, and five of these little units under every sergeant, so now in the Earthly Paradise at large there shall be four families linked to every corporal’s family, and twenty-five such family units under the guidance of every sergeant. Each one of these communities shall build a public granary, and also a chapel for public worship, in which the sergeant shall make his dwelling. Every Sabbath day, the corporal shall take his own family and the four others under his command to the chapel, to worship there, and men and women shall sit in separate rows as they listen to the sermons from the sergeants and sing praises to the Heavenly Lord. Every seventh Sabbath day, all senior officers, from the generals to the captains, shall visit one of the churches of the sergeants under their command, both to preach to them and to check that all in their congregations work hard and obey the Ten Commandments. Every single day the children will go to the chapel to hear their sergeants expound the Bible and the sacred Taiping texts.1

By day the people will work their land, but all must serve, when time allows, as potters, ironsmiths, carpenters, and masons, according to their skills. As to the land of China, all shall divide it up amongst themselves, with one full share for every man and woman aged sixteen and above, and half a share for every child below sixteen. All the land will be graded according to its productivity, and the shares handed out accordingly, with each person receiving land of varying richness, from best to worst. When the land is insufficient for the people’s needs, the people will be moved to where the land is plentiful. Let every family in each unit rear five chickens and two sows, and see to their breeding. Let mulberry trees be planted in the shelter of every house, so all can work at raising silkworms and spinning silk. Of the products of this labor—food or cloth, livestock or money—let each corporal see to it that every family under him has food for its needs, but that all the rest be deposited in the public treasuries. And let the sergeants check the books and tally the accounts, presenting the records to their superiors, the colonels and captains. For “all people on this earth are as the family of the Lord their God on High, and when people of this earth keep nothing for their private use but give all things to God for all to use in common, then in the whole land every place shall have equal shares, and every one be clothed and fed. This was why the Lord God expressly sent the Taiping Heavenly Lord to come down and save the world.”2

From the public treasuries, gifts shall be made to every family at times of birth, marriage and death, according to their need, but never in excess of one thousand copper cash, or one hundred catties of grain. No marriage should be treated differently because of the family’s wealth, and these rules shall apply to all of China, so that each community has a surplus in case of war or famine. And at every ceremony, the sergeant shall lead his families in the worship of the One True God, making sure that no superstitious rites from days of old are followed.3 From every family unit with a living male head, one person shall be chosen to serve as a soldier in the army; but the widowers and widows, the orphans and the childless, the weak and the sick, need not serve, but will receive food for their needs from the public treasury.4 As births and new marriages or the Taiping’s advances lead to new families joining the ranks, from every five such families a new corporal shall be created, and from every twenty-five a new sergeant, and so on up the ranks. Reports of merit even of the humblest soldier shall also be passed up the ranks from sergeant to lieutenant and so to the Heavenly King himself, so that promotions can be made and rewards given. All officers and officials, even the highest, shall be reviewed every three years, and promoted or demoted according to performance.5

Though all of this ideal system cannot be implemented at once, at least the listings and the rosters can be prepared and reviewed so that when the times allow, the Taiping leaders will be ready to act. From the earliest days of the Taiping’s entry into their Heavenly Capital of Nanjing, censuses have been taken of the people, and the lists kept up to date and duly passed up through the ranks.6 From the details entered on a specific family record, such as that of the Liangs, one can see whence they have come, the extent of their loyalty, and who is left still to serve. Liang himself, now thirty-four, born and raised in Guiping, joined the Taiping forces at Jintian in August 1850; in September he was named a sergeant, in October raised to captain. After the capture of Yongan he was raised to colonel and then to general, in which rank he still serves. His father is deceased in Guiping, his mother is a general of the women’s Fourth Rear Army. His wife holds a position in the office of court embroideries; his sister is an official messenger in the North King’s court. His children still are under age. Of his three brothers, one has died in combat, two are currently not serving in the Taiping army.7

The military rosters, by contrast, do not list every family member, but give the age and provenance of each soldier, so their commanders can check their careers and capabilities at a glance. Thus Sergeant Ji, in the Thirteenth Army’s forward battalion, now twenty-six, is also a Guiping man, who joined the Taiping at Jintian in September 1850, and rose to sergeant after the capture of Wuchang. His assistant sergeant Wang, only eighteen years old, was born in Wuchang and joined the Taiping when they took the city in January 1853, and named to assistant sergeant after the capture of Nanjing. Sergeant Ji’s five corporals are aged nineteen, thirty-five, twenty-six, thirty, and twenty-three, and are all from the provinces of central China, not from Guangxi. The private soldiers in their squads range in age from seventeen to fifty-one. Six other men are listed as soldiers in the platoon, but classified as “off-the-registers” because of youth or age. One of these men is fifty-nine, the other five are youngsters, whose ages range from eleven years old to fifteen.8

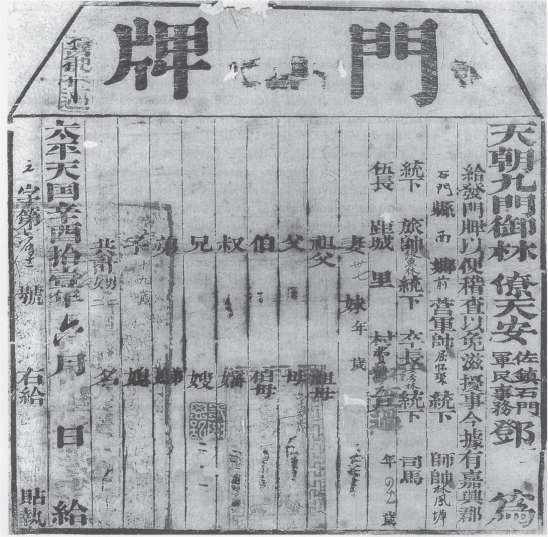

Taiping household register. Registration forms of this kind were issued by the Taiping authorities to all households in the areas that came under their control. The information on such forms enabled the local Taiping military commanders (whose names are entered on the right-hand side of the form) to calculate taxes due, and the availability of family members for military service. In this example, the household head is listed as being a certain Fei Heyun, aged forty-one, resident of a village in the western sector of Shimen county (some fifty miles northeast of Hangzhou in northern Zhejiang). With Fei live his wife, aged thirty-seven, his mother of sixty-two, and a son aged nineteen. To prevent any chance of the form being tampered with, a column on the left records that this household contains two male and two female residents. The document is dated the sixth month of the Taiping Kingdom’s eleventh year, equivalent to July 1861 in the Western calendar, when the Taiping were at the peak of their expansion into the coastal region of China.

Not everyone flocks eagerly to the Taiping ranks. Households are often reluctant to register their members, and prevaricate for weeks, sometimes until threatened with death for their delays. Some Nanjing residents hide out in their own or close friends’ homes, on some occasions walling off back areas of their courtyards and trying to conceal their family members there. Some hide themselves in closets if the Taiping come, while others simply live in the wooded hills of deserted areas of the city, the huge extent of which makes such a fugitive existence possible even in the midst of the Taiping’s own Heavenly Capital.9 One ingenious merchant establishes special institutes to manufacture luxury embroideries and face powder for the women’s quarters of the Taiping leaders, which assures the workers he employs of special perquisites and freedom to roam in search of rare materials, for the Taiping women dress boldly and garishly, and are heavily made-up, despite the puritanical pronouncements of their leaders. The same merchant, emboldened by his success, gets permission to assemble squads to gather firewood in the outer suburbs, and transport it to the capital in boats; many use this brief taste of freedom to vanish altogether into the countryside.10

In areas recently occupied by the Taiping, where the locals are not known at all to the occupiers, the local villagers and townspeople are left free to choose their own corporals, sergeants, and lieutenants, by whatever criteria they choose. They are even handed the blank forms in bulk, so they can circulate them in their neighborhoods, and omit none of the information on family members that the Taiping require of them. Once the rosters have been checked by Taiping officers, each household is issued an official doorplate with the relevant information written on it, to be publicly displayed as proof they have complied with the regulations of the Heavenly Kingdom.11

The problems of dealing with the followers of non-Taiping religions are handled by the leaders in different ways. Taoists and Buddhists get short shrift: the numerous Taoist and Buddhist temples within Nanjing’s walls, many of them treasures of architecture centuries old, are burned to the ground. The statues and images are smashed, the priests are stripped or killed. Those who survive must conform to the new Taiping religion, and Taiping soldiers preach the new religion with drawn swords in their hands, to underline the message.12 But the Chinese Muslims in Nanjing are not attacked so savagely, and the mosques already established in the city are allowed to stand.13

One group of religious Chinese in Nanjing are in a position of particular ambiguity, because of their apparent closeness to the Taiping troops’ beliefs—these are the Catholic converts, who number about two hundred. In the brief days of siege before the Taiping storm the city, these families store all their valuables for safekeeping in the mansion of the Ju family, for they are the wealthiest Catholics in the city. But one day after the Manchu citadel has fallen, the Ju family home is commandeered as the residence for a senior Taiping official, and all the property is confiscated for the common treasury. At least thirty of the Catholics are burned in their homes or cut down in the streets, during the first harsh days of chaos, before order is restored.14

The survivors gather in the Catholic church, where Taiping soldiers find them; when the Catholics refuse to recite the prayers according to the Taiping liturgy, they are given a three-day grace period, but warned that thereafter death will be the penalty for those who still resist. Good Friday is on the twenty-fifth of March in 1853, and as they begin their service of the adoration of the cross Taiping soldiers burst into the church, breaking the cross and overturning their altar. The seventy to eighty Catholic men, arms tied behind their backs, are given a rapid trial before a Taiping judge, and condemned to death unless they say the Taiping prayers. They refuse, expecting martyrdom. But for no clear reason a reprieve is given, and while their womenfolk and children gather in the church, the men, still bound, are locked in a nearby storehouse, where they spend their Easter Sunday. By the day after Easter, twenty-two of the Chinese Catholic men have recited the Taiping prayers, finding nothing in them that specifically contradicts their faith. The others, still obdurate, are sent off to serve at the front as soldiers—where ten desert—or as laborers.15

In order to make all the necessary registration forms, and also to print enough Bibles and copies of the Taiping sacred texts for all the sergeants who need them for their reading and preaching, it is necessary to marshal the forces of the printing industry of Nanjing. The ranks of the local printers are swelled—after the Taiping capture of Yangzhou in April 1853—by numbers of Yangzhou craftsmen relocated to Nanjing, some of them masters at using metal movable type, fonts of which had been brought north by officials once stationed in Canton. The headquarters for these Taiping printing operations, suitably enough, are in the former Temple of the God of Literature, revered by Confucian scholars.16

The forms are easy to make, and require little skill, but the word of God is a different matter. It seems to be chance—or the fact that this is the particular edition that the Heavenly King has with him for several years for his own use and study—that leads the Taiping to rely on the version of the Bible translated by Karl Gutzlaff in Hong Kong, rather than any of the various other versions available, including later corrected versions by Gutzlaff himself.17 The first book of the Bible that the Taiping publish is the Book of Genesis, chapters 1 through 28, from the creation of the world through Jacob’s dream of the ladder, on which the angels ascended and descended to and from Heaven. Though Genesis has fifty chapters altogether, the Taiping leaders close this opening volume with the words of the True God to Jacob at the end of chapter 28, for these will have especial force to anyone among the Taiping faithful who can read or hear:

And he dreamed, and behold a ladder set up on the earth, and the top of it reached to heaven: and behold the angels of God ascending and descending on it. And, behold, the Lord stood above it, and said, I am the Lord God of Abraham, thy father, and the God of Isaac: the land whereon thou liest, to thee will I give it, and to thy seed; and thy seed shall be as the dust of the earth, and thou shalt spread abroad to the west, and to the east, and to the north, and to the south: and in thee and in thy seed shall all the families of the earth be blessed. And, behold, I am with thee, and will keep thee in all places to which thou goest, and will bring thee again into this land; for I will not leave thee, until I have done that which I have spoken to thee of.

And Jacob awaked out of his sleep, and he said, Surely the Lord is in this place; and I knew it not. (Genesis 28:12–16)

Even though the Chinese translation is not that fluid or perfect—and at times not even clear—the Taiping block carvers are instructed to print all twenty-eight chapters directly from Gutzlaff’s text, just as they find them, not excluding the numbers of each verse that are inserted among the columns. There is only one exception, something the Taiping leaders find so shameful that they cannot put it in their people’s hands. That is the last eight verses of Genesis 19, where Lot, after the destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah, and the death of his wife, retreats with his two surviving daughters to a cave above Zoar. Hong himself knows full well, from his Confucian texts, and his experiences at Thistle Mountain and Guanlubu, the paradoxes that can attend the filial child who seeks to perpetuate the family line. But this story is different from any in the Chinese tradition, as Lot’s eldest daughter speaks to her sister:

And the first-born said unto the younger, Our father is old, and there is not a man in the earth to come in unto us after the manner of all the earth. Come, let us make our father drink wine, and we will lie with him, that we may preserve seed of our father. And they made their father drink wine that night: and the first-born went in, and lay with her father; and he perceived not when she lay down, nor when she arose. And it came to pass on the next day, that the first-born said unto the younger, Behold I lay last night with my father: let us make him drink wine this night also; and go thou in, and lie with him, that we may preserve seed of our father. And they made their father drink wine that night also: and the younger arose, and lay with him: and he perceived not when she lay down, nor when she arose. Thus were both the daughters of Lot with child by their father. (Genesis 19:31–38)

Faced with the moral implications of such a passage that they have no means to explain away—especially given their own insistence on the force of the seventh commandment—the Taiping leaders cut the verses altogether, continuing the Bible story with Genesis 20. In practical terms, the cut is easy, for the offending verses fall at the end of a chapter, and there is no problem of continuity between Lot’s flight from Zoar and the story of Abraham and Abimelech, which follows.18

With at least four hundred men in Nanjing employed in the job of transcribing the characters and carving the blocks, the Taiping work moves swiftly forward. The rest of Genesis is published, and Exodus too, by the summer of 1853. By winter, with the numbers working on the printing project grown to six hundred craftsmen, the Taiping complete Leviticus and Numbers from Gutzlaff’s version, faithfully transcribing the long lists of odd-sounding names and the minutest dietary and sacrificial details, and making no further cuts, for there is less that they find shocking here. Amidst the maze of technical details, one can find important reinforcement for the Taiping’s own precise regulations for the listing and organizing of the faithful, even though in the Bible the troops are older, and women are not included:

And the Lord spoke unto Moses in the wilderness of Sinai, in the tabernacle of the congregation, on the first day of the second month, in the second year after they were come out of the land of Egypt, saying, Take ye the sum of all the congregation of the children of Israel, after their families, by the house of their fathers, with the number of their names, every male by their polls; from twenty years old and upward, all who are able to go forth to war in Israel: thou and Aaron shall number them by their armies. And with you there shall be a man of every tribe, every one head of the house of his fathers. (Numbers 1:1–4)

Also that winter the Taiping publish the first of the Gospels, that of Matthew, in its entirety.19

Nanjing is, for now, the Heavenly Capital, and to protect it the great Taiping armies are divided into three: one to defend the city itself, one to sail and march back up the Yangzi River to recapture and consolidate control over the cities bypassed—or captured and abandoned—in the headlong rush downriver in the spring of 1853, and one to march overland to the north, cutting through the heartland of China and threatening Peking itself.20 In either December 1853 or January 1854 those with enough education to write a polished essay who have stayed on in Nanjing are invited by the Taiping leaders to submit essays on the three major strategic decisions that Hong Xiuquan has taken: the selection of Nanjing as the capital, the Taiping printing and publishing program, and the altering of place-names in China.

In praising the choice of Nanjing as the Heavenly Capital, the various scholars assemble a range of reasons: the direct intervention and support of God and the Elder Brother Jesus are of course central factors. But also emphasized by many are more mundane topics: the city’s high, thick walls, its full granaries, its favorable topography—“like a crouching tiger and a coiling dragon”—the “elegant, simple, and generous” customs of its inhabitants, and the prosperity of its markets and its agricultural hinterlands. Others write of Nanjing’s admirable river communications, the city’s reputation as a “realm of happiness,” its “concentration of material wealth” and location as a prime grain-producing area, the wideness of its streets, its historical resonance as a prosperous and fortunate city, and its natural role as the end of a geographical and temporal sequence that brought the Taiping armies from Thistle Mountain through Yongan to Wuchang.

Riskily but boldly, one of the scholars, a native from the Guiping area of Guangxi who once passed the licentiate’s examination that Hong Xiuquan failed, brings up the problem of the right to rule. Across all time, he writes, since God first created Heaven and earth, there have been those who have turned against their rulers; thus “regicide and usurpation were frequent, and chaos and change continued until the present.” But this process, far from being repeated by Hong, was by his goodness brought to a close. For “our Heavenly King personally received God’s mandate and will eternally rule over the mountains and rivers. The righteous uprising in Jintian signaled the formation of a valiant and invincible army, and the establishment of the capital in Nanjing lays an everlastingly firm foundation. The capital is called the Heavenly Capital in accordance with Heaven’s mandate, and our country is called the Heavenly Kingdom in consonance with God’s will.”21

In praising the printing in Nanjing of an official list of Taiping publications, each marked with the royal seal of approbation on the title page, the scholars serving the Taiping again speak much of divine will and of Hong’s majesty. “When Heaven produces an extraordinary man, it must have an extraordinary task for him to do. When Heaven has an extraordinary task, it must have an extraordinary treasure to facilitate its completion.” But some talk with more precision of the need to purify the Chinese language after its corruption by the “demonic language and barbarian words of the Tartar dogs.”22 Other scholars praise the use of such seals on the books as a proof of authenticity at this early period of the Heavenly Kingdom when “authenticity and falsehood of books are hard to distinguish.” Particularly when such books are circulated among the armies in the field, “suspicion may be mixed with belief and the demons use all sorts of tricks.” Furthermore, since the restructuring of literature and of culture is one of the prime proofs that a true leader has once more emerged on earth, spreading such clearly authenticated books will show all people, great and small, near and far, that such a new leader is now come.23 Yet other scholars link the word of God on earth as exemplified in three books especially, the Old Testament, the New, and Hong’s own proclamations. With these three circulating in authenticated editions, “the road to Heaven is now in sight,” and the day of their “secrecy” will be over; all other works such as those by Confucius and his follower Mencius, along with the “various philosophers and hundred schools,” can be safely “burned and eliminated, and no one be permitted to buy, sell, possess, or read them.”24

The third public task given to the scholars assembled in Nanjing is to comment on Hong Xiuquan’s proclamation that henceforth the city of Peking be named the “Demon’s Den,” and the province of Zhili, in which Peking is situated, be called the “Criminal’s Province.” At once arcane and direct, Hong’s purpose here is to brand the very language given to the region where the Manchus dwell as tainted and improper. Peking, the administrative capital of the Manchu empire, is set in the northern province of Zhili, a name that can be interpreted as “correct” or “attached.” Since “the demons have defiled that region,” writes Hong, “and the ground they tread is involved in their crimes,” the name must be changed to “Zuili,” “criminally attached province.” Similarly Peking, “the northern capital,” must also be abandoned as a name, since there can be no capital other than Nanjing, the Southern and Heavenly Capital. In all military reports and future orders, the former Peking shall be called Yaoxue, the “Demon’s Den.” When all the demons have been exterminated, the original name of Peking will be restored. And when all in the Criminal’s Province “have repented of their sins and begun to worship God our Heavenly Father,” then the Criminal’s Province too will have its name changed. But in honor of this transformation it will be given, not its old name, but a new one, “Province Restored to Goodness.”25

The scholars all praise the celestial wisdom of this proclamation, and their arguments complement each other and overlap. In condemning the more than two hundred years in which the northern region has been occupied by the Manchus, they point to the region’s perversions, its dishonesty, its love of idolatry and rejection of the One True God, its gambling and opium smoking, and the slavish nature of the Chinese living there. They also imply that the Manchus are now driven into a corner, and that this is the last area left to them. “With such a small territory,” they ask, “how can the demons resist the heavenly troops?” In “their ludicrous self-importance” the Manchus have named their “caves and dens” as an upright province. But having behaved so unpardonably, they have been condemned for all time by the Heavenly Father and Heavenly Elder Brother, Jesus. “Their crimes are too flagrant to be tolerated, and their viciousness is so excessive as to make their extermination certain.” Thus the area that the Manchus think they can call their own is in fact “a prison erected by Heaven.”26

Behind Hong’s proclamation, however, lies a deeper truth, a truth about language. Almost all the writers acknowledge in a general way the importance of changing the names to “Demon’s Den” and “Criminal’s Province,” and praise Hong for his wisdom in doing so. But only one, Qiao Yancai, later to be rewarded with the highest honors in the Taiping’s newly instituted examination system, gives a slightly fuller explanation of why this should be so: “The world has long been deluded by these demonic Tartars, and it is imperative that they be soon destroyed. But before we destroy these people, we must first destroy their bases. And before we can destroy the power of their bases, we must first destroy the bases’ names.”27

It is not only place-names that have this kind of force and resonance. When the presence of the devil demons runs through other names, then they too are changed. Thus Xianfeng, the reigning emperor and by definition leader of the earthly demons, whose name in its correctly written form means “united in glory,” has his name rewritten with a dog component added to the original characters, so all can see his dog-like nature. And the word Ta, used unflatteringly already as a way to refer to barbarian nomads or “Tartars,” is also given a dog component so that all Manchus are mocked alike. The temples where both the Manchu demons and the Chinese idolators worship their false gods are also given their own mocking character, a new coinage that shows that the truth is absent within them.28

Other words are freshly created because certain components are too tainted to be used. The words for “soul” and “spirit” fall into this category, whether their basic meaning concerns our animal, sentient, or inferior souls that bind us here on earth, or the spiritual, upward-tending divinely oriented souls that are ours throughout eternity. When the component in such words is gui, used commonly for the dead, the spirits and the demons, it is removed, and the simple component for “human being” is used instead. Thus it is our human nature, not our demonic one, that urges us toward our God.29

Some characters that represent the forces of the highest good must of course be retained, if no impurity adheres to the composition of the character, but they must then be forever tabooed for any other use. Ye, huo, and hua are three of these, for they are the ones used to represent the word Jehovah; the characters used to transliterate “Jesus” and “Christ” are also banned from all other use, and accepted substitutes are clearly stipulated, as are those for “Heaven,” “holy,” “spirit,” “God” and “Lord,” and “elder brother.” The words for “sun” and “moon” must also be written in an altered form, for the original characters in all their purity are reserved for Hong Xiuquan himself, the Sun, and his true wife in Heaven, “the First Chief Moon.” The personal names of all five Taiping kings are tabooed from other use, whether like Feng Yunshan and Xiao Chaogui they have left this mortal life, or like Yang and Wei and Shi Dakai they still lead the Taiping troops in earthly combat. The family name of Hong Xiuquan himself, the Heavenly King, also is forbidden to others, replaced by different characters with the same pronunciation.30

Yet Hong’s name can be incorporated in newly coined characters when their majesty is great enough. The character for the “rainbow” of God’s covenant with Noah, pronounced “Hong,” like the Heavenly King’s own name, is banned from general use. But the new character created in its place, of a rain cloud above and a flood (or Hong) beneath, reminds all who read of the disasters striking earth before the covenant was made. Other characters that can be ambiguous or even sound obscene if pronounced with the Cantonese, Guangxi, or Hakka accents of many of the God-worshipers are changed accordingly. Three of the terms for cyclical days in the calendar are changed for these reasons, and euphemisms are designed for certain basic human functions. For the government of the Heavenly Kingdom, too, certain new words are created: a word for “true unity,” another for “pure justice,” one for “glory,” and one for “distribution by boat of needed food supplies.”31

The inclusion of a word for “food supplies” in such a list highlights a material problem for the Heavenly Kingdom. Since Yongan, or even earlier, the Taiping have been drawing largely on contributions—some given from religious fervor, others coerced—and from the loot of captured cities put into the common treasury. The huge city of Nanjing, lying in the midst of fertile farmlands, densely cultivated, offers ample food for a time, but there are too many Qing armies in the area to enable the Taiping faithful to establish the units of five families led by their corporals and guided in morality by their sergeants in any permanent form. And questions still remain about the permanence of the Heavenly Capital. If the northern armies overthrow the Qing, will not the Demon’s Den, as Hong has promised, be freed from its opprobrium, and the Criminal’s Province blossom anew as Province of Restored Goodness?

To highlight the differences between the Heavenly Capital and the Demon’s Den, Yang Xiuqing, the East King, has told the Taiping faithful that it is not yet time to end their period of sexual separation.32 Men who force themselves on women, even if they are veteran soldiers from Guangxi with accumulated merit, must be executed, and even married couples arranging for clandestine reunions, when caught, are sternly punished. Some will seek to avoid these prohibitions by resorting to prostitutes, but that too is strictly forbidden, and enforcement backed by group involvement; those who work as prostitutes, or those who use them, will not only themselves be executed but so will their families. Anyone in the community reporting such improper acts to Taiping authorities, however, will receive special rewards.33 Male homosexuality is punished with similar severity; if the partners are both aged thirteen or older, both shall be beheaded. If one is less than thirteen, he shall be spared and his partner beheaded, unless the child was an active partner, in which case he too is killed.34 Even the sending out of clothes by the men to be washed or mended by women in the town is carefully scrutinized and may be harshly punished, for “with this type of intimate contact, love affairs between them cannot be prevented.” To avoid the chance of sin, all men should wash and mend for themselves.35

Like Wuchang, the city of Nanjing is divided into blocks of men’s quarters, and those for women and their children. Within these blocks, as far as practicable, people are arranged, by sex and occupation, into their groups of twenty-five, called guan. The world of city life is naturally different from the countryside, and within Nanjing itself the dream of labor shared in common yields to specialization, to keep the people and their leaders sheltered, clothed, and fed. Thus among the guan are those for bricklayers, carpenters, and decorators; for tailors and shoemakers; for millers, bakers, soy sauce and beancurd makers; and, in a sense overarching all others, those for medical care, fire fighting, and the burial of the dead. All these workers are meant to labor for the public good, and draw their food from the common treasury.36 The women are marshaled under their own female leaders—older Guangxi veterans—and clustered in buildings near the Xihua Gate in squads of around twenty-five also called guan. The numbers of women under Taiping control grow dramatically, as the cities around Nanjing are seized and occupied by Taiping troops.37

To make these newly captured cities true bastions of defense, all commerce and traveling merchants are forbidden inside their gates, and the women and children are shipped off to the Heavenly Capital, leaving the teenage boys and fighting men to guard the walls of the garrison towns. The common treasury sees to the maintenance of these uprooted people in Nanjing. In the stripped-down cities, as also in Nanjing, to preserve security all regular trade and markets are forbidden within the city walls. Whatever supplies can be found must be bought at the stalls clustered around the city gates, where the local farmers soon set up stands for meat and fish, and even teahouses; though the Taiping officers, always watchful, often order that even these little shops be separated by sex, some for male and some for female customers. These stocks can be supplemented by foraging or purchase in the countryside, and by privately arranged barter or trade.38

The people of the Heavenly Capital react to these new impositions in many ways—some stay in hiding, some plan to flee, some plot to poison or overthrow the occupiers, others join the Taiping ranks with varying degrees of passion, yearning for the restitution of some family life.39 There are extra employment opportunities for many people, since though the lieutenants, sergeants, and corporals supervise the lives of their dependent families at the local level, the Taiping kingdom now has a growing bureaucracy of men and women, all with their own staffs and assistants. As the East King explains the situation in a message to Hong Xiuquan: “As a consequence of the great mercy of the Heavenly Father and the Heavenly Elder Brother in sending our ruler, the Second Elder Brother, down into the world to be the true ruler of the ten thousand countries under Heaven, and to establish the Heavenly Capital, heavenly affairs have daily increased in complexity and in number, and people are needed to assist in the administration.”40

The six central government ministries, with their elegant archaic names drawn from the Rites of Zhou—the Ministries of Heaven, of Earth, of Spring, Summer, Autumn, Winter—are largely honorific, the real work being done in the more than fifty departments and agencies ranked under them. These oversee the treasuries and granaries that supply the Heavenly Kingdom. They provide the personnel to supervise the storehouses of gunpowder and shot that supply the armies on campaign, to manufacture war vessels, to provide the robes and embroideries for the kings and their palace women, and to preserve the heavenly decrees and other sacred texts. There are also staff positions for the procurement of cooking oil, salt, and firewood, for the goldsmiths, and for the supplying of fresh water.41

Sometimes the various skills must flow together, as with the symbols and calligraphy of the new hats that the Taiping rulers design for themselves. The ceremonial hat for Hong will have a fan-shaped front and be decorated with twin dragons and twin phoenixes. The other kings may each have twin dragons as well, but only a single phoenix. On the upper part of his hat the Heavenly King—and he alone—shall have the embroidered words “the mountains and rivers are unified” and on the lower part the words “the heavens are filled with stars.” The three other surviving kings shall each have one line of embroidered calligraphy: for East King Yang, the characters “Lone Phoenix Perching in the Clouds”; for North King Wei, “Lone Phoenix Perching on the Mountain Peak”; for Shi Dakai, the Wing King, “Lone Phoenix Perching on the Peony,” accompanied—as a gesture to his youth?—with a single embroidered butterfly.42

One group of skilled practitioners constantly in demand are doctors, for most of the scholars specializing in these arts left Nanjing for the shelter of Shanghai or other cities as the Taiping troops approached. In a great city such as Nanjing, there is always the danger of disease, but to the city’s normal needs are added now the exigencies of war, with the attendant wounds, the presence of many additional women and their children, some separated from their families at short notice in nearby towns, and the East King, Yang Xiuqing, whose problems with his eyes and ears had kept him from the front lines of leadership for a time in Thistle Mountain. Thus the Taiping proclamations, issued by the North King, invite all those living in Taiping areas who have skills at curing diseases of the eyes, handling children with convulsions and other illnesses, and special knowledge of obstetrics to make their names known to any Taiping commanders in their area. Those doing so will be given special escorts to the Heavenly Capital and—if their skills are real—high-ranking office and a huge cash payment of ten thousand taels (each tael roughly one ounce) of silver. Their term of service completed—the length of time is nowhere specified—they will “be sent back to their native place in peace.”43

The North King expresses regret that doctors have not responded in the past to Taiping pleas, but hopes now that the higher rank and cash payments will be sufficient inducements. “None should hide their talents,” for they were given to them by God “for benefit of all mankind.”44 Enough doctors are attracted by these or other means at least to staff the hospitals for the seriously ill—known, so as not to discourage the patients, as “institutes for the able-bodied”—and to provide some basic medical care in each of the sixty zones into which the Heavenly City has been divided. Others are assigned to the neighboring garrison towns, to help those wounded in combat.45

The Heavenly Capital needs fitting palaces for the kingdom’s rulers. Part of the Taiping plan is implemented here, in that all those with skills at carpentry, masonry, and decoration are called to pool their skills and labor to create the palaces. Ten thousand people work for six months on the splendid palace built for their Heavenly King, ten times grander than the former magistrate’s residence in Yongan. This palace rises on the site of the former governor-general’s mansion, at the center of the northern side of the main residential city.46 After the first few days of the occupation, the leaders move into the main city, using what is still salvageable from the old buildings in the ravaged Manchu citadel to decorate their grand new palaces. When Hong’s almost completed palace complex accidentally burns down, in late 1853, as many more hands—some from Nanjing and some from neighboring provinces—are recruited to rebuild among the ruins, and to decorate the walls and pillars with the colorful paintings of birds, animals, and mountain scenery that the leaders seem to value most.47

Much of the energy and cost for building goes not into palaces but into defense of the Heavenly Capital, or the newly conquered or reconquered towns that lie beyond. Within Nanjing, the great city gates are at first cleared of the obstructions and the sacks of earth put there by Qing troops in their fruitless defense. But within a few days, under the constant threat of counterattacks by government forces, the gateways are reinforced with stone, and the passageways through them narrowed so that only one file of people at a time can pass through; the gates themselves are repaired, and additional gates built in front of or behind the existing ones, so that one leaf at a time can be opened without rendering the whole defensive system vulnerable. Emplacements for cannon—two per gate—are constructed, and special encampments reinforced with palisades for the gunners and the other troops on gate duty. At intervals across the city, and beyond the walls in the forward defensive encampments, wooden watchtowers are raised, to a height of thirty or even forty feet. Here veteran soldiers stand the watches, supplied with colored flags to make the signals that can warn from which direction any demon attacks are launched.48

The smaller towns nearby—though lacking Nanjing’s mighty walls and gates—are defended with a care designed to give even the largest demon army pause; the houses near the city walls are burned or torn down to remove the possibility of cover, and the open spaces crisscrossed with ditches, palisades, and felled trees with obtruding branches. Whole areas are honeycombed with small round holes, a foot across and two feet deep, lightly camouflaged with grass or straw, so that any rapid movement or transportation of heavy loads is impossible. Between these barriers lie fields of sharpened bamboo stakes, their spikes four inches or so above the ground, so sharp they rip bare feet and go through any shoe, so close together that only by moving slowly one step at a time can one pass through them. Tens of thousands of such stakes are made and sharpened by the civilian populations of the occupied towns, working as ordered through the nights. Where stone for walls is lacking, the doors and floors of all the city houses have been commandeered and fastened in serried rows to two high lines of posts, five feet or so apart, and the space between them filled with pounded earth.49

Beyond the walls of the heavenly havens, in the land the Taipings pray will soon become the Earthly Paradise, the war is one of guile and cruelty. Just as the demons find it hard to pierce walls so defended, so the heavenly troops are cautious when they venture forth to cities abandoned by the enemy. The Taiping troops are warned by their commanders, “The demons sometimes bury gunpowder and shot under the ground and camouflage it with straw, fresh earth, or bamboo leaves. Sometimes they conceal a bow and arrow so that anyone coming in contact with it releases the arrow. Sometimes they conceal spikes or iron nails under wooden bars, or sometimes they dig pits.” Umbrellas, apparently abandoned on the ground, conceal shot and gunpowder in their handles, which are triggered when the umbrella is opened. Precious objects lying on the ground are linked to fuses and explode when one picks them up. Even innocent-looking documents may contain concealed arrows or explosives that fire or erupt when the document is opened. Such demon tricks “cannot be detected by the eye,” the troops are told. Anticipation and wariness are the only methods of defense.50

Secure for now behind the stakes and walls and ditches, with the watchers in their towers around him, and his women at his side, Hong Xiuquan surveys his kingdom. He knows that the naming of all under Heaven is now within his personal purview. It is his royal writing brush that contains all things, all mysteries. As once the vocabulary of China’s children was learned from the Thousand Character Essay, which gave the essence of the language to those who had mastered their “Three Character Classic,” so now the subjects of the Heavenly King will learn from Hong’s own “Imperially Written Tale of a Thousand Words” not only the history of their origins but the very words with which to phrase them:

Our Great Lord God

Is One. There is no other.

In the beginning He showed his skills,

Creating Heaven and earth.

When the myriad things were all

complete

He gave life to men on earth,

Dividing lightness and darkness

So day and night came in succession.

Sun and moon each shone their light,

Stars and constellations formed an order.

The winds reached to the four directions,

Fierce and harsh they blew.

Far off, the clouds gathered

And rain fell from the void.

After the flood waters ebbed away

God in compassion made a Covenant:

Never again to send such a deluge—

The rainbow would stand as His sign.

He slew the devils, wiped out the demons,

Thunder crashed and lightning struck.51

Now that Hong’s name is in the rainbow, he partakes both of God’s wrath and of His mercy. The proof of this, for the Heavenly King, is in the present:

The capital is established near Zhong Mountain;

The palaces and thresholds are brilliant and shining;

The forests and gardens are fragrant and flourishing;

Epidendrums and cassia complement each other in beauty.

The forbidden palace is magnificent;

Buildings and pavilions a hundred stories high.

Halls and gates are beautiful and lustrous;

Bells and chimes sound musically.

The towers reach up to the sky;

Upon altars sacrificial animals are burned.

Cleansed and purified,

We fast and bathe.

We are respectful and devout in worship,

Dignified and serene in prayer.

Supplicating with fervor,

Each seeks happiness and joy.

The uncivilized and border peoples offer tribute,

And all the barbarians are submissive.

No matter how vast the territory,

All will eventually be under our rule.52