What magic intersection of timing, fate, and providence can found our Earthly Paradise upon the rock? The homage demanded from the foreign visitors, and the excoriation of Emperor Xianfeng and all his followers as demon dogs and foxes, cannot hide the realities of boundaries that shift in response to the exigencies of war, and of a Heavenly Capital that turns in upon itself.

The Taiping leadership has followed an ambitious strategy, which has worked only in part. To capture the Demon’s Den of Peking city, they have dispatched in May 1853 a dedicated Taiping army of some seventy thousand veteran Guangxi men and new recruits on a northern march, but God has not blessed the enterprise. The Qing forces have kept them guessing with false intelligence reports designed to suggest the advance of huge Qing armies to the south, while their real troops and local militia forces mount spirited defenses of small towns, slowing the marchers unexpectedly. The terrain of northern China is unfamiliar, and progress further hampered by the Qing government’s appointment of a special officer whose only task is to keep all boats on the northern shore of the Yellow River as the Taiping troops approach, making it impossible for them to repeat the triumphs of their earlier 1852 campaigns on the Yangzi.1 Even when the Taiping troops do capture medium-sized cities, Qing commanders have now been instructed to burn all their stocks of food and gunpowder if the Taiping storm their walls—and though some are reluctant or too tardy to comply, those who do so reduce the chances of the Taiping resting and restocking their supplies. Forced much farther to the northwest than they have planned, the Taipings at last cross the Yellow River, but are caught unprepared by savage winter weather, which freezes many in their tracks or leaves them maimed from frostbite—“crawling on the snowy, icy ground with their legs benumbed”—for they are southerners, and not equipped with proper winter clothes. Reinforcements, sent to their aid, are also checked or turned back by local Qing forces, for the Taiping have not kept a main supply route from north to south open and defended at any point on the vast battlefield.2

Astonishingly, by late October 1853 one of the thrusting Taiping columns pushes to within three miles of the outskirts of Tianjin, from which they might have opened up a path to nearby Peking, but they can get no farther. New Qing and local forces, including Mongol cavalry, are sent against them. Despite the initial enthusiasm of many local people for the Taiping message, and the military help of secret societies and the members of new rebel organizations like the Nian—who are also locked in struggle against their landlords and the government—the Taiping blunt their popularity. Their search for food and clothing grows desperate, and the massacre of all one town’s civilian population sends a wave of fear ahead of them.3

Swiftly though the Taiping can build defensive redoubts, for they are veterans at this kind of warfare—throwing up earthworks, digging ditches, and crisscrossing open ground with foxholes in a single day of frenzied work—the Qing are learning to encircle these encirclements, recruiting thousands of local laborers from the farming population to build a solid ring around the Taiping forces. By May 1854, with the remnants of the Taiping vanguard forces thus encircled, the Qing commander orders a long ditch built to divert the waters of the Grand Canal to a dried-out riverbed that flows near the Taiping fortified position. The work takes a month, but slowly as the water enters its new channel the Taiping camp turns to mud, and then to a lake; the soldiers can neither sleep nor cook, their gunpowder is waterlogged and useless, and as they climb onto roofs, cling to ladders, or float on homemade rafts, the Qing troops pick them off in groups and execute them. So, ingloriously, die the warriors after fighting and marching over a one-year period for close to two thousand miles.4

Had the northern campaign had full call on all Taiping resources, perhaps it might have succeeded, and the criminals’ province been renamed. But it is matched by a parallel campaign to the west, planned and executed on a similar scale; swiftly, also, this western campaign splits into two, as part of the army fights for a strategic base in Anhui province, on the northern shore of the Yangzi River, while the other part moves upriver to recapture Wuchang city, and extend the Taiping river and supply lines to China’s southern hinterland. This Wuchang campaign then subdivides, as one group of Taiping armies regains, loses, and recaptures yet again the city of Wuchang, while others push southward into Hunan, seeking once more to seize Changsha. This Hunan campaign splits in its turn, as General Shi Dakai swings south to attack Jiangxi province, southwest of the Heavenly Capital.

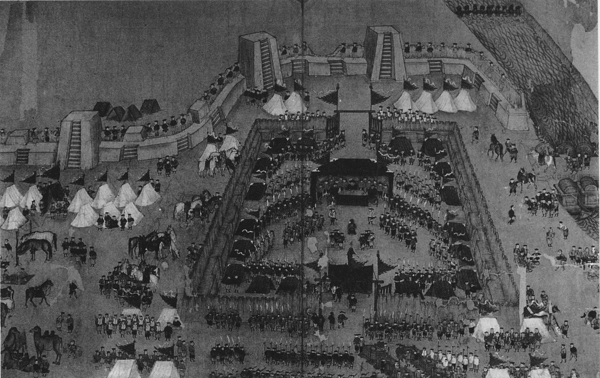

The Taiping northern campaign of 1853—1855. In the summer of 1853, after Nanjing was consolidated as the Heavenly capital, Hong Xiuquan sent an army north to seize the Qing dynasty’s capital of Peking. By October, the Taiping army of around thirty thousand men reached the suburbs of Tianjin, less than seventy miles from their goal, but here they were checked by the Qing forces and slowly driven back. After vainly fighting to hold a succession of towns, the Taiping northern army made a last stand in the Grand Canal city of Lianzhen, where they held out during an eight-month siege until they were annihilated in March 1855.

These four illustrations are from a series of ten, probably commissioned from a local artist by the grateful merchants of Tianjin as a gift to the victorious Qing commander, General Senggelinqin. The pictures show the Taiping being burned and driven out of two towns, until Senggelinqin surrounds their last bastion of Lianzhen with a ring of earthern walls and gun emplacements. In the last illustration, the defeated Taiping general Lin Fengxiang is shown kneeling before Senggelinqin, whose supply trains, camels, cavalry horses, and gun positions are all clearly delineated. Lin was subsequently executed. Credit: Harvard-Yenching Library, Harvard University.

Some of these campaigns succeed and some do not: Changsha cannot be taken, nor can Hunan be held, for the gentry of Hunan have learned in full measure how to recruit, train, and pay militia armies, while Zeng Guofan, a Confucian scholar-bureaucrat at home to mourn his parents, joins forces with the reinstated governor Luo Bingzhang, and by integrating their land and naval forces slowly build a formidable fighting force.5 Wuchang, however, is recaptured by the Taiping general Chen Yucheng, aged eighteen at the time, nephew to a senior Taiping veteran but already a brilliant military strategist. The city becomes their inland base, easy of access up the Yangzi River from the Heavenly Capital.6

In Anhui province, the battles swirl for years around the strategic city of Luzhou, held for a time by another gentry leader, Jiang Zhongyuan, hero of Suoyi ford, promoted for his valor to be Anhui governor. The Taiping seize the city at last, having developed a new strategy of digging double tunnels one above the other, and lining them with explosives attached to time-spaced fuses. After the first explodes, the Qing defenders rush to mend the gaping holes, and are just completing their repairs as the second explosives fire, killing the wall menders and reopening a gaping hole through which the Taiping charge. Jiang commits suicide. But though the Taiping hold Luzhou stubbornly for twenty-two months, until November 1855, they are at last starved out, betrayed, and stormed.7 In Jiangxi province, Shi Dakai links up his forces with tens of thousands of Triad Society troops who have been fighting for possession of Canton city and, though failing in that endeavor, have escaped northward up the river Gan. Uniting these various armies, and receiving clear support from the local people, Shi makes most of the province a center of Taiping government and a rich source of food supplies, save for a small circle of land around the city of Nanchang on Poyang Lake, where Zeng Guofan, sent there from Hunan, just manages to hold the city’s defenses intact.8

With all these massive campaigns in progress, the constant shift of victories and defeats, the endless search for new recruits and supplies, the Taiping can do little toward the east of their Heavenly Capital, even though the resources there are rich. Indeed even as they threaten and hold cities hundreds of miles away, the Qing press hard upon their central base. It is all the Taiping’s locally based forces can do to hold Zhenjiang, less than forty miles downriver, the key to the approaches to the Grand Canal and the Heavenly Capital; while Qing garrison armies are encamped in force in the hilly countryside just a few miles outside the walls of the Heavenly Capital, in a series of interlocking bases from which the Taiping have never had the time or resources to dislodge them. These Qing troops are so near that they are able to keep secret communications open with anti-Taiping loyalists within the city, and to enforce the rules on their own dress and customs, so that local farmers bringing their produce to the informal markets outside the city gates often still have the shaved forehead and long plait of hair mandated by their Manchu masters.9

Of the surviving Taiping kings, only Shi Dakai, the Wing King, is constantly occupied in the field, directing and personally leading the different phases of the western campaigns. The Heavenly King, Hong Xiuquan, as spiritual leader, bestower of rewards and punishments, and ultimate supervisor, stays in his palace. Wei Changhui, the North King, acts as coordinator for the defense of the region around the Heavenly Capital, and sees to its food supplies. General administrative supervision is in the hands of the East King, Yang Xiuqing, who also acts as coordinator of all the military campaigns. Other Guangxi veterans, mainly from Thistle Mountain and Guiping, have mansions in the city and have been enfeoffed with noble ranks—they serve either in the field or as senior officials in the Heavenly Capital.10 But despite the formidable system of post stations and communications both by land and by water that the Taiping rapidly establish—with post stations ten miles apart, special bureaus to chart the weather, and couriers carrying their special seal of a flying horse surrounded by clouds, and disguising themselves as merchants or peasants when demon patrols are blocking the routes—the fronts change so often along with the areas controlled by the Taiping that most generals on specific campaigns have to be left a wide area of initiative. The river town of Wuhu, for example, some fifty miles upriver from Nanjing on the south shore of the Yangzi, and an important center for commerce and communication, changes hands eight times between 1853 and 1855 alone.11

It is at the end of December 1853 that Yang Xiuqing changes the rules as they have begun to coalesce, and begins to speak once again publicly as the voice of God. This is the first clear move in a sequence that will take Yang himself and thousands of other Taiping followers to their death. The timing and the precise motivation for the change are ambiguous. The news from the northern expedition is bad but not yet disastrous, and Yang has ordered massive reinforcements to move north from Yangzhou; the western expedition has temporarily stalled, but has already achieved remarkable successes; and the French have visited Nanjing on the Cassini and left again without making any offers of support despite Taiping encouragement.

The visitation is announced abruptly, in the middle of a working day, after the North King and other senior officials have conferred with Yang about their administrative duties. Four of Yang’s palace women officials, with their assistants, are the only ones with him, and it is to these women that God first speaks through Yang’s mouth. God’s message to these women is that Hong Xiuquan, the Heavenly King, has grown both harsh and indulgent with his power: harsh to the women who serve in attendance on him, and indulgent to his son the Young Monarch, now four years old. In particular, four of the palace women who work for the Heavenly King—the message names them individually—should be released from their palace duties with Hong and sent to live instead in the palace complex of Yang, the East King. Their duties could be taken over by any of Hong’s other palace women. By the time the North King and the other Taiping officials arrive, God has returned to Heaven, so kneeling they receive the message from the women of the court. In a second swift visit through Yang, this time at the court of Hong Xiuquan, God orders the Heavenly King to receive forty blows of the rod for his derelictions. Only when Hong prostrates himself to receive the blows does God forgive him and return to Heaven.12

The charges of harshness and indulgence are then discussed by Yang Xiuqing: the Young Monarch, Hong’s four-year-old son, is self-indulgent and willful—he plays in the rain, despite the possible harm, and that must be stopped. He smashes presents that he is given, and that too must cease, lest as a ruler in the future he abuse the people.13 The harshness to the women has also taken various forms: when palace women dig an ornamental pool for Hong, he treats it as a general might a military operation, ordering them to work through rain or snow. The concubines have been allowed to sneer at and scold the women officials, preventing them from doing their duty in the palace, and when the women officials are attending to such details as repairing palace rooms or sweeping the protected inner gardens, the Heavenly King is always criticizing and interfering, terrorizing those who work for him. In his anger, too, Hong has kicked or otherwise punished his royal concubines, even when they are pregnant. However serious their crimes, none should be disciplined by violent means until her time is up and the child is born.14

These are the East King’s elaborations of God’s words, but on this and another occasion two days later he gives his own related thoughts, couched in the form of a “loyal memorial” from a concerned minister rather than as the direct commands of God. Yet it is clear that Hong is expected to respond to Yang as if Yang’s own words were God’s. In the running of the Taiping kingdom, the most important change is that Yang now arrogates to himself the power to decide all cases that might call for the death penalty. Yang also would refer back to Hong Xiuquan those cases in which clemency might be granted. Thus Hong’s “naturally severe disposition” and tendency to order “wrongful executions” would be mitigated by Yang’s sensitivity to “unredressed grievances” that would linger in the Heavenly Capital if people were “hastily put to death.” The result of this new arrangement would be that “the Heavenly Father’s intent in fostering human life will be eternally displayed, and the spirit of gentleness and tranquility will be handed down through all eternity.”15

On two other matters in the same December meetings Yang overturns previous decisions of Hong Xiuquan, both seeming inconsequential, but each cutting, in some way, at the heart of Taiping practice or belief. One is an appeal to Hong to lessen the severity of prohibitions of “family visits” among those loyal Taiping women followers who “forgot their homes for their country, and forgot themselves for the public good.” The “single-minded devotion” of such loyalists should be rewarded by allowing them “home visits” once every twenty or thirty days, or maybe every Sabbath, so they can see to their children, attend to their elderly in-laws, and “serve their husbands.”16 As to the world of ritual and pomp, here also changes should be made. Dragons, for example, with their ritual implications of imperial glory and grandeur, should be separated out from “demons” with whom they have been indiscriminately lumped by Hong Xiuquan as Heavenly King, in his passion for extirpating demons. Yang states that dragon palaces, dragon robes, and dragon vessels are all honorable, and should not be confused with the devil serpent of the Eastern Sea and his demon minions, who betray the souls of men.17

This discussion—or conflict—over ritual goes back to the roots of the formation of the God-worshipers in Thistle Mountain, or perhaps earlier to Hong’s visions of 1837. For in that vision, and as constantly retold in Taiping texts, and even revisited in the minds of Hong’s disciples, the figure of God the Father was wearing a black dragon robe in Heaven.18 In 1849, Hong’s loyalest followers were promised that if they persevered and were victorious one day they would wear dragon robes and horn belts, whereas if they did evil they would be killed.19 During the early campaigns of 1850, Hong’s own rural retreat was euphemistically known as the Golden Dragon Palace, and was visited by all the leading Taiping commanders, including Yang Xiuqing.20 Hong Xiuquan defends himself by saying to Yang that their Elder Brother, Jesus, long before in the Thistle Mountain area came down to earth and announced that “dragons are demons” although “the dragon of the Golden Dragon Hall was not a demon but a truly precious creature,” and Hong chose to focus on the first part of these remarks and not the second.21

One of the inner Taiping texts, not yet distributed to all the Taiping followers but known to Hong—and surely to Yang as well—quoted Jesus’ remarks in the Pingnan Mountains, autumn of 1848, as follows:

“Hong Xiuquan, my own younger brother, can it be you do not know the astral prophecy of the dragon demon? The dragon of the sea is this same leader of the demon devils, and he that the people of the world call the devil Yan Luo is that same dragon of the Eastern Sea. He is the one who can change his form, and deceives the souls of those who live on earth. When you some time ago came up to Heaven, and together with the great army of the Heavenly Host fought against that square-headed red-eyed demon devil leader, that too was him. Have you now forgotten that?” And the Heavenly King replied, “I would have forgotten had my Heavenly Elder Brother not reminded me.”22

In glossing this sacred text in the direction desired by Yang—as Hong forthwith meekly does, with the words “From now on, whenever dragons are engraved by our Heavenly Kingdom or Heavenly Court, all shall be considered as precious golden dragons, and there is no need to regard them with glaring eyes”—Hong has in fact yielded up a point in a longstanding argument over imagery and iconography, and their relationship to idolatry.

It is essential to Hong Xiuquan, if he is to keep his paramount position within the Taiping movement, that the central truth of his journey to Heaven not be disputed. Yang may speak with the voice of God, but Hong has seen and talked with God, recorded the color of His beard and clothes, and has seen and talked with Jesus. Thus when he is presented with a lengthy text in Chinese that argues the Christian doctrine with great force and yet denies that God can have material nature, Hong alters it with care before releasing it as a Taiping sacred text. Hong makes both deletions and additions. He deletes the statement “God is immaterial and invisible,” adding instead the sentence “He can be seen only by those who ascend to Heaven.” Hong also cuts a longer passage that runs as follows: “God is without form, sound, scent or taste; we can neither observe His form, nor hear His voice, nor feel nor perceive Him by any bodily organs.” And Hong substitutes for this and other lengthy passages of similar import remarks designed to humanize the God whom he has seen, such as the homely metaphor “When the house leaks God can observe it.” Thus purged and amplified, the text is published as a Taiping sacred work in 1854.23

Simpler on the surface, but perhaps deeper in theological implications, is the formal declaration by Hong that henceforth Yang Xiuqing shall bear a new title in addition to those he already possesses. Because of the solace the East King has brought him by his frankness and fearless honesty, says Hong, Yang shall be called the “Comforter” and the “Wind of the Holy Spirit,” the phrase that the Taiping use to translate the “Holy Ghost,” or third person of the Trinity. By conferring this title, says Hong, he consciously echoes the words used by Jesus, who “addressed his disciples, saying ‘At some future day the Comforter will come into the world.’ ” Hong is here referring to the fourteenth chapter of John’s Gospel, which—though not yet published by the Taiping—has been in his possession for several years in Gutzlaff’s Chinese translation. According to John, at the end of the Last Supper, Jesus tells his anxious disciples, “I will pray to the Father, and he shall give you another Comforter, that he may abide with you for ever.” Jesus also says, “The Comforter, which is the Holy Ghost, whom the Father will send in my name, he shall teach you all things, and bring all things to your remembrance, whatsoever I have said unto you” (John 14:16 and 26).

The phrase “Holy Ghost,” so central in the Christian idea of the Trinity, is muted in this early Chinese translation. But there is no denying that when Hong says to Yang that “the Comforter and the Wind of the Holy Spirit spoken of by our Heavenly Elder Brother is none other than yourself,” he has ventured into new and difficult terrain, especially since Hong knows well the passage in John’s first epistle, where it is written, “For there are three that bear record in heaven, the Father, the Word, and the Holy Ghost: and these three are one.”24

That Yang, through deliberate manipulation of Hong, is here moving to a higher stage in the Taiping hierarchy can be suggested by the chilling reference to the Comforter that follows those quoted by Hong. For in John’s Gospel, chapter 16, verse 7, Jesus also says, “I tell you the truth; it is expedient for you that I go away: for if I go not away, the Comforter will not come unto you; but if I depart, I will send him unto you.”

Yang is aiming high, and when you aim high, others must fall. Two of Hong Xiuquan’s closest and most trusted associates are also publicly humiliated by Yang in God’s December visitations. One of these is the North King, Wei Changhui; the other is the marquis Qin Rigang. Both have been with Hong Xiuquan from his earliest days at Thistle Mountain. Wei, a man with some education, gave all his family possessions to the God-worshipers after they helped him in his local village; Qin, while working as a miner, also studied military arts and became a formidable strategist. For years both men have handled key military assignments for Hong, and Qin is regarded as the senior-ranking Taiping officer after the surviving kings.

Yang uses his claim to speak for God to humiliate North King Wei in many ways. Whenever God appears, Yang’s women attendants summon the North King at once with drum calls; if Wei is late, it is the women who relay God’s messages to him. When Yang is speaking with God’s voice, Wei must kowtow in full prostration before him. When Yang is in a trance in his sedan chair, Wei must walk, not ride, beside him. Even Yang’s stewards keep Wei jumping, by refusing to disturb their master to clarify the messages or to see if his trance has ended. Qin has to endure similar humiliations and even has to help carry the East King’s sedan up the palace steps.25

The December clash between the East and North Kings includes one other confrontation that illustrates how each maneuvers for position with Hong Xiuquan, East King Yang to prove his own morality, North King Wei to show his support of Hong’s imperial perquisites. The incident starts when Yang suggests that Hong has more than enough embroideries and robes in his palace, and should economize for a time instead of acquiring more. The North King, ignoring Yang, replies to Hong:

You, our second elder brother, are the true Sovereign of all nations of the world, and you are rich in the possession of all within the four seas; although robes and garments are sufficient, it will still be necessary to be constantly engaged in making up more.

To this clear challenge to his own authority, the East King responds as follows:

I beseech you, our second elder brother, to pardon this younger brother’s crime and permit this younger brother to memorialize straightforwardly. If apparel were insufficient, then it would be necessary to make up more; but if it is said it is sufficient, it will be better to delay the making up of more, and then we can see the second elder brother’s virtues of economy and love of man. Why should our younger brother Zheng [the North King] memorialize on the necessity of constantly making up more clothing?

Faced by these conflicting claims, the Heavenly King praises Yang, saying:

Brother [Yang Xiu]Qing! You are certainly what the ancients called a bold and outspoken minister. And you, brother Zheng, although you may have a sincere regard for your elder brother, are not so straightforward and open in your statements as our brother Qing; for which he is to be much more commended. Later, in the reign of the Young Monarch, all who are ministers should imitate the example of our brother Qing in speaking straightforwardly as he has done this day; thus will they fulfill their duty as ministers.26

The humiliation of Marquis Qin is more indirect, but after he and the East and North Kings have been treated to a banquet by the Heavenly King, in honor of their presence at God’s visit, he is firmly reminded by Hong that he is not in the inner circle of Hong Xiuquan’s “brothers” and that such special grace, rare already, will not be repeated once Hong Xiuquan has departed this world, for Qin is, and will remain, only a “minister” and not a king.27

This distancing of Qin does not however mean that Yang accords North King Wei the same kingly dignities he claims for himself, any more than he does Shi Dakai, the Wing King, who in any case is away most of the time directing the western campaign and poses no current threat to Yang. What Yang has done, with Hong’s apparent agreement, is structure an inner “family” of four brothers, with Jesus the eldest, Hong Xiuquan the second, and Yang himself the fourth. (The third place in this sequence was either allotted to the South King, Feng Yunshan, now safely dead, or to Hong’s eldest son, Tiangui, still only four years old.)28 In an abbreviated history of the Taiping movement and its beliefs, written by two of Yang Xiuqing’s close advisers and issued on his personal orders in 1854, Yang is described as being “personally ordered by the Heavenly Father to descend into the world, to become the Senior Assistant and the Chief of Staff of the Heavenly Kingdom, to save the hungry and redeem the sick, and to rule the younger brothers and sisters of all nations throughout the world.”29 In the same text Yang’s “Holiness” is distinguished from the “eminence” of the other kings, just as the “kindness and liberality” of Yang the Comforter is separated from the mere “tolerance” of the other kings.30

On March 2, 1854, God pays another visit to earth through the mouth of Yang. This time, His message is in two parts. One part is again directed against the veterans from Guangxi, especially those of the highest ranks, just below the kings; three of these men are manacled and lectured on duty and morality before they are released. Two other men, senior Guangxi veterans, are brought forward and accused in front of all their colleagues of sleeping with their wives on four or five occasions, instead of following the Taiping prohibitions of sexual love until such time as final victory over the demons has been won. One of these men—now a minister at court, and in earlier days the collaborator with Hong Xiuquan on the expanded Taiping version of the Ten Commandments—is given a pardon after he makes a full confession. The other is condemned to death, along with his wife, by being beheaded in public, on the grounds that they tried to suborn their female staff from revealing the news of what they had done.31 In making his accusations, God through Yang reminds the Taiping officials of the penetrating power of his vision, which has led him to unmask traitors in the Taiping ranks on crucial occasions in the past, both in the Guiping region and in occupied Yongan. By pinning this scrutiny to the intimate activities of the bedchamber, Yang even more strongly makes the point that no one can escape God’s all-seeing eyes and Yang’s network of informers.32

In the second part of his March message God speaks through Yang of the fundamental virtues that are embedded in China’s classical texts. God first states his position elliptically, through a riddle-like couplet:

The heroes of old are never lost to us,

For their achievements have been preserved for us in the pages of books.

Once the Taiping officials, on God’s urgings, have done their best to explain this utterance, God through Yang gives his own elaboration:

“You should ask Fourth Brother [Yang] to notify your Heavenly King that among the ancient books which were condemned as demonic are Four Books and Thirteen Classics which advocate Heavenly feeling and truth. These books exhort people to be filial and loyal to their country. For this reason, East King requested me to order the preservation of those books. You should keep the books in compliance with truth, filial piety, and loyalty, but destroy those which celebrate sensual desire and absurdity. Historical writings throughout the ages, in venerating good and condemning evil, have inspired filial piety and loyalty among people, motivating them to kill rebellious officials and prodigal sons. The absolute moral standard which they advocate is crucial to social mentality and ethics. Moreover, since I created Heaven and Earth, most of the faithful men and heroes I have sent down have been responsible persons. These heroes are not necessarily demons, so their names are recorded in various writings and last forever. How could you destroy those books and erase the names of these figures? I have sent down the Heavenly King to rule the world. This is the right time for our heroes to help establish the Heavenly Law and exterminate evil. Those who remain loyal to Heaven are also motivated by immortal fame which will inspire later generations to be loyal. Also, there is no need to avoid the word shen (god); the same goes for many words which before were regarded as taboo. From now on, the dragons drawn from Heavenly Court should be guarded by five paws, since four paws signify a demonic serpent. The chief minister can adopt the phoenix as his symbol.”

All the woman officials kneeled down and listened to the Heavenly Decree. Each of them promised to follow the Heavenly Father’s instruction. The Heavenly Father returned to Heaven.33

In thus reasserting that certain core values of the Chinese past are preserved for all time in the Confucian classics, and can be ignored only at the Taiping’s peril, Yang is striking at the heart of the doctrine that Hong Xiuquan has put together across so many years. Originally, it was Hong himself who was the scholar, filling his early pronouncements with echoes from his reading and Confucian moral judgments. But slowly the versions of his vision of 1837 came to contain more details of God’s anger with Confucius, and even of Confucius’ public humiliations; in the Thistle Mountain years, Jesus, through the mouth of Xiao, also joined in the chorus of condemnation. This was made clear in an account of a visit by Jesus to the Taiping mountain retreat in the winter of 1848:

Heavenly King asked Heavenly Brother: “How is Confucius doing in Heaven?”

Heavenly Brother: “When you ascended to Heaven, there were a few occasions on which Confucius was bound and whipped by Heavenly Father. He once descended unto the world and instructed people with his writings. Although he had some good points, he often made great mistakes. All his books should be burnt during the Age of Great Peace [Taiping]. However, since Confucius can be generally regarded as a good person, he is allowed to enjoy happiness in Heaven, so long as he does not descend again.”34

A similar message, linked to anti-Manchu patriotic slogans designed to win over secret-society membership, was reiterated during the campaigns of 1852 and 1853, in the names of both Hong Xiuquan and Yang Xiuqing. But now, with the city of Nanjing, with its large population and many scholarly inhabitants, as the temporary—perhaps permanent—Heavenly Capital, Yang seeks to establish his own reputation as the preserver of eternal values. His declarations to Hong, which have been recorded and distributed to the people of Nanjing, not only show his special powers as God’s mouthpiece but are also larded with references to the role of the virtuous ministers and moral exemplars drawn from the Confucian classics, especially to the central text, the Confucian Analects.35

In so appealing to mainstream Confucian values Yang Xiuqing also shows an awareness of the deep unhappiness of many people—both the educated elite and the uneducated—with the Taiping occupation. Gentry militia leaders like Zeng Guofan, who are now building up their own regionally based army forces in a sustained effort to hold back the Taipings, have shown themselves fully alive to the importance of this war over moral values, and able to fight back with pronouncements of their own. As Zeng phrases it in a proclamation widely distributed in central China at this time:

Since the days of T’ang, Yu, and the Three Dynasties, the sages of all ages have been sustaining the traditional culture and emphasizing the order of human relationships. Hence, ruler and officials, father and children, high and low, honored and humble, were as orderly in their respective positions as hat and shoes which can never be placed upside down. Now, the Yueh [Taiping] bandits steal some dregs of foreign barbarians and adhere to the religion of God; from their fake king and fake ministers down to the soldiers and menial servants, they address one another as brothers, alleging that only Heaven can be called father. Aside from this, all the fathers of the people are brothers and all the mothers are sisters. The farmers cannot cultivate their own fields to pay taxes, because it is said that all the land belongs to the Heavenly King. The merchants cannot do their own business to make profits, because it is said that all the commodities belong to the Heavenly King. The scholars cannot read the classics of Confucius, but they have others called the doctrines of Jesus and the book of the New Testament.

In short, the moral system, ethical relationships, cultural inheritance, and social institutions and statutes of the past several thousand years in China are at once all swept away. This is not only a calamity in our great Qing Dynasty but is, in fact, the most extraordinary calamity since the creation of the universe, and that is what Confucius and Mencius are crying bitterly about in the nether world. How can all those who study books and know the characters sit comfortably with hands in sleeves without thinking of doing something about it?36

Yang’s reassertion of certain traditional Chinese values overlaps with the Taiping discovery of a plot to open the gates of Nanjing secretly to the Qing forces encamped outside. The leader of this conspiracy, Zhang Bingyuan, is a holder of the licentiate’s degree that Hong had failed to pass, an alert and inventive man, who by the time his plot is discovered in March 1854, has recruited in person and through intermediaries, an estimated six thousand disaffected soldiers and Nanjing residents. His plan secretly to open one of the eastern city gates at dawn so the Qing troops can storm inside is foiled only by the dilatoriness and suspicions of ambush by the Qing commander. There is also a disastrous muddle in which one party plans its armed link according to the Taiping calendar while the other calculates according to the traditional Qing calendar; since the two calendars use the same terms for dates that are in fact six days apart, the mistake is discovered only when it is too late.

Yang’s subsequent uses of the power he has wrung from Hong Xiuquan in December 1853—to be the ultimate arbiter of death sentences in legal cases—is given ironic substance by Zhang Bingyuan’s fatal subtlety. For when Zhang is first arrested, and charged with attempted treason by a Taiping informer, he convincingly insists the informer is an opium addict, who acted as he did because he was afraid that Zhang would turn him over to the authorities. For this crime the informer is executed on Yang’s orders before all his charges against Zhang have been substantiated. When the main plot is unraveled and Zhang is interrogated by Yang’s agents, he blithely lies again, naming thirty-four of the most talented Taiping military officers as his co-conspirators. Only when all thirty-four have been summarily executed do the Taiping leaders find they have been duped into doing themselves much of what Zhang himself had hoped to achieve. The final execution of Zhang can not atone for all these Taiping dead.37

The contradictions in Taiping text and policy are now so pronounced that they can hardly be concealed. But it is not only on Confucian ground that the battle is being joined. In the biblical world as well tensions and ambiguities are pressing to the fore. Hong Xiuquan, as God’s second son and Jesus’ closest younger brother, obviously has a kind of primacy over Yang as “fourth brother.” Yet with Xiao Chaogui now long dead and the voice of Jesus stilled, Yang’s double claims as voice of God and “Comforter and Wind of the Holy Spirit” give him two places in the structure of the Christian Trinity, while Hong has consistently and consciously denied the nearness of any force to God Himself. Just as Jesus himself is lesser than his father, so is the Comforter and Wind of the Holy Spirit only an emanation rather than an equal force. Moreover, though other Taiping leaders have traveled up to Heaven, and met at intervals with the Father, Son, and others in the holy families, it is Hong Xiuquan’s revelation of 1837 that is the decisive one, with his vision of the golden bearded God in black dragon robe, and his special nearness to Jesus’ wife and children, his elder sister-in-law, and his son Tiangui’s first cousins. But how can such claims be balanced or evaluated in all their complexity, since no one in the Taiping leadership has training in theology, and Issachar Roberts has been banned from visiting the Heavenly Capital by the American commissioner, punctilious about the neutrality of the United States in the current war?

Providence, which works in many ways, gives Yang an opportunity to test the waters. It is the British who occasion the opportunity. Frustrated by their experiences with the Hermes in 1853, they have sent no more formal diplomatic visits. But in late June 1854 they can no longer contain their curiosity. Claiming the need for the British in Shanghai “to ascertain whether a supply of coals can be provided for the public service” from the Taiping, since coal is rumored to be stored in Wuhu, which has been intermittently under Taiping control, the British minister sends a small mission under Captain Mellersh of the Rattler to investigate the options. The two junior British diplomats assigned to the mission are further instructed to find out everything they can about the current state of Taiping life and belief—“their political views, their forms of government, their religious books, creeds and observances, their domestic and social habits, and all facts respecting them which seem entitled to notice.”38

Reaching Nanjing on June 20, 1854, the British are denied permission to enter the city or its suburbs, and no Taiping come to their ship. Frustrated, they submit to Yang, the East King, thirty questions on a wide variety of topics—trade prospects, troop numbers, laws, tariffs, initiation rites, examinations, the common treasury, separation of males from females, opium prohibitions, ranks of nobility—and two intrusive ones on a matter of different import: what does it mean when Hong Xiuquan says he is Jesus’ younger brother; and why, among his many titles, does the East King include those of “Comforter” and “Holy Ghost”? Yang’s answer comes promptly, in a large yellow envelope, one foot wide and eighteen inches long. Though often evasive or elliptical, on the questions relating to Hong’s identity and his own titles he is more direct, and the British interpreter at once translates Yang’s answers:

To your enquiry (as to whether and why I received the appellation of “the Comforter,” “the Holy Ghost” and as to the meaning of the titles “Honae Teacher” and “Redeemer from Disease”) I reply, that the Heavenly Father appeared upon earth and declared it as his sacred will that the Eastern Prince should redeem the people of all nations upon earth from their diseases, and that the Holy Ghost should enlighten all their blindness. The Heavenly Father has now pointed out the Eastern Prince as the Holy Ghost, and therefore given him the title of “Comforter, Holy Ghost, Honae Teacher and the Lord who redeems from disease,” so that all the nations of the earth may know the confidence placed in me by the Heavenly Father in his mercy. . . .

To your enquiry (whether you are to infer by the designation given to Jesus of Celestial Elder Brother and that given to the Celestial King of Second Elder Brother, that the latter is actually the child of God, or that he is so only by allegory) I reply, that the Celestial King is the second son of God, truly declared to be by the Divine Will of God. The Celestial King likewise ascended up to Heaven in his own person and there again and again received the distinct commands of God to the effect that he was the Heavenly Father’s second son and the true sovereign of the myriad nations of the globe. Of this we possess indubitable proof.39

In return, Yang poses fifty questions of his own to Captain Mellersh; in their range and nature, the first thirty of them show with great clarity the questions that are troubling the Taiping Celestial Court about their heavenly claims. The East King writes:

The questions I have to ask are these—

You nations having worshipped God for so long a time, does any one among you know,

1. How tall God is, or how broad?

2. What his appearance or colour is?

3. How large his abdomen is?

4. What kind of beard he grows?

5. What colour his beard is?

6. How long his beard is?

7. What cap he wears?

8. What kind of clothes he wears?

9. Whether his first wife was the Celestial Mother, the same that brought forth the Celestial Elder Brother Jesus?

10. Whether he has had any other son born to him since the birth of Jesus his first born?

11. Whether he has had but one son, or whether, like us mortals, a great many sons?

12. Whether he is able to compose verse?

13. How rapidly can he compose verse?

14. How fierce his disposition is?

15. How great his liberality is?

You nations having worshipped God and Jesus for so long a time, does any one among you know,

16. How tall Jesus is, or how broad?

17. What his appearance or colour is?

18. What kind of beard he grows?

19. Of what colour his beard is?

20. What kind of cap and clothes he wears?

21. Whether his first wife was our elder sister?

22. How many children he has had?

23. Of what age is his eldest son?

24. How many daughters has he had?

25. Of what age is his eldest daughter?

26. How many grandsons has God at this moment?

27. How many granddaughters has God at this moment?

28. How many heavens are there?

29. Whether all the Heavens are of equal height?

30. What the highest Heaven is like?40

The remaining twenty of Yang’s questions refer to specific problems of interpretation of New Testament passages, to the role of the “Comforter,” to the nature of the Taiping mandate from God to destroy the Manchus, and the significance of Britain’s alleged stance of neutrality. With a sharper touch, in the fiftieth question Yang notes, “You have the audacity to presume to impose upon us in spite of ourselves, and without any sense of propriety to represent that your object in coming to the Celestial Kingdom is the desire to get coals.”41

The small group of foreigners on the Rattler—none of whom has theological training either—form what they sardonically call “a synod” with Captain Mellersh for the purpose of answering Yang as well as they can, locating apposite passages to answer specific points, and moving thoroughly through all fifty of his questions. For questions one to eight, the answer is that God has neither height nor breadth. On nine to eleven, God as spirit does not “marry,” and has no son but Jesus. For twelve to fifteen, God is always merciful, and nothing to Him is impossible. On sixteen to twenty, the New Testament gives no information. On twenty-one to twenty-seven, references to the “marriage of the Lamb” as found in Revelation can only be understood figuratively, as the “union of believers with Christ.” Twenty-eight to thirty are unknowable.42 But though these answers to the specific questions are courteous and thorough, the British “synod” ’s summary of their conclusions and reflections reads harshly indeed to Yang:

In reference to your closing declarations, such as that God has specially commissioned you and your people to exterminate the imps—that your sovereign is God’s own son, and the uterine brother of the Celestial Elder Brother—that he is the true sovereign of all nations—that you, the Eastern King, are appointed by God to the office of the Holy Ghost, the Comforter—I think it right to state to you distinctly that we place no faith in any one of your dogmas to this effect, and can subscribe to none of them. We believe only what is revealed to us in the Old and New Testaments, namely, that God the Father is the creator and Lord of all things—that Jesus is his only begotten son—that he came down into the world and became flesh—that he died on the cross to redeem us from our sins—that after three days he rose again from the dead, and ascended into heaven, where he is ever one with God—that he will appear once again hereafter to judge the world—that those who believe in him will be saved—and that those who do not believe in him will be lost—that the Holy Ghost is also one with God—that he has already been manifested among men, namely, shortly after the ascension of our Lord—that now those who pray for his influence will receive him in their hearts and be renewed thereby—and that these three, the Father, the Son and the Holy Ghost, are the one and true God.43

And the Englishmen reiterate, in conclusion, that in all problems of doubtful interpretation Yang should follow Christ’s simple injunction: “Search the Scriptures, for in them ye think ye have eternal life, and they are they that testify of me.”44

This letter is sent to the East King on June 29, 1854; next day the Rattler leaves Nanjing for Shanghai, where the vessel docks on July 7. The Taipings have not allowed them to ship a single lump of coal, but safely stowed on board are copies of the latest books to have left the Taiping presses, Leviticus, Deuteronomy, and Joshua, which carry the story of the wandering tribes of Israel from the death of their leader Moses to their final entry into the Promised Land, which he was fated never to see. Also on the ship is Hong’s revision of the text on the nature of God, with its painstaking attempt to argue for the propositions that the “synod” has just refuted.45 That same day of July 7, in Nanjing, God speaks again through the mouth of Yang. The message is brief and unprecedented in the history of the Taiping movement:

“Your God has come down to you today for one reason and one reason only: namely to inform you that both the Old Testament and the New Testament, which have been preserved in foreign lands, contain numerous falsehoods. You are to inform the North King and the Wing King, who in turn will tell the East King who can inform the Heavenly King, that it is no longer useful to propagate these books.”46

When God, through Yang, asks the assembled Taiping officials to comment, there is little for them to say. One veteran Taiping general protests that he, being illiterate, can hardly consider the merits of such a decree; another, who has a scholar’s training in the old society, and senses what answer Yang really seeks, replies that “there can be no mistakes in the sacred instructions of Our Father or Our Eldest Brother,” clearly implying that the messages relayed to earth by Xiao and Yang are the pure revelation, while the written text itself can be seen as suspect. God replies through Yang: “Those books are neither polished in literary terms nor are they fully complete. You must all consult together, and correct them so that they become both polished and complete.”47

The challenge to Hong Xiuquan, and to his followers, is unmistakable: the biblical word of God, which has carried them all so far, is now to be altered by the hands and minds of men. But the words of God as revealed through Yang are correct in every detail, and none shall presume to alter them.