Issachar Roberts leaves Nanjing on January 20, 1862, and seeks shelter on a British ship moored in the Yangzi River. In indignant letters to the press, he claims he has been greatly wronged by the Shield King, Hong Rengan, and that Hong Xiuquan is “a crazy man, entirely unfit to rule [and] without any organized government.”1 Reporting Roberts’ safe arrival at Shanghai in early February, the North China Herald shows little sympathy for the preacher it has already sarcastically dubbed “His Grace the Archbishop of Nanking” and a “sham Diogenes of former days, and would-be Plato among missionaries.”2 Roberts’ flight, to the paper’s editors, is merely poetic justice for the man who had misled the public for years about the Taipings. “Even he who first lighted the match which has led to such a wide-spread conflagration of blasphemy and murder has at last fled from the monster he has conjured up—like Faust fleeing from the demon Mephistopheles.”3

Roberts’ flight from the Heavenly Capital comes just as General Li Xiucheng, determined this time to face down the foreigners and make up for the disastrous losses at Anqing, has massed new Taiping armies outside Shanghai. Confirmation of the nearness of the Taiping troops, their strength, and their readiness for combat comes to the Western community from two of their own, one drunk, one sober, but both experienced in the ways of war. The first of them, Charles Goverston, is a seaman on a British vessel, the British Empire, moored in Shanghai harbor. Given a forty-eight-hour “liberty” to explore Shanghai in early January 1862, as he explains subsequently to the British vice-consul, he overstayed his leave “through intoxication.” Not yet “perfectly sober,” he sets out “with a Chinaman who could talk English,” to take a look at the vaunted Taiping, and finds them all too quickly. Suddenly surrounded by a squad of Taiping troops, only two or three miles from the shelter of the city, Goverston is terrified, indeed “the fright quite sobered him,” though he swiftly returns to his former state when a Taiping officer gives him more “liquor to drink which quite capsized him.” But thereafter, the terror gone, and no more drink provided, Goverston is held by the Taiping and questioned for four days through his Chinese companion-interpreter. The questions focus on whether there are French and English troops in Shanghai, where and how many, whether they are also in the Chinese city, and whether they have heavy guns. The interrogation finished, the Taiping give Goverston a message to take back to the foreigners: the Taiping request the French and British to withdraw from the city, which the Taiping are determined on taking. They undertake not to damage any European property, and not to plunder.

Neither too drunk nor too terrified to keep his eyes open, Goverston estimates the Taiping troops just in his area of confinement to number about fifteen thousand men: “The villages all around are full of them: every house crammed.” Many of the Taiping are armed with foreign muskets, some with “the Tower-mark,” others German-made. There are several Europeans with the Taiping forces, and one English-speaking “Arab” who acts as “servant” to a Taiping officer. The Arab tells Goverston there are other Taiping armed with the latest Enfield rifles. Goverston notes that the Taiping troops seem well fed and fit, “very fine-looking men” with “plenty to eat.” But they treat their conscripted Chinese coolie laborers with great cruelty, killing those who cannot manage their loads; nor do they pay their foreign helpers, but promise that when Shanghai is taken they will “get lots.”4

On January 20, 1862, another Englishman, Joseph Lambert, gives an even more detailed description of Taiping plans and troop strengths to the British officials. Lambert has been one of the supervisors, with a European “mate,” on a fleet of forty-two boats sent by Chinese merchants under the French flag to buy silk up-country. Arrested by the Taiping, held for three days, and interrogated through an English-speaking Cantonese in the Taiping force, the foreigners are threatened with death, but are spared when their employer offers their captors two thousand dollars. Lambert is then ordered to return to Shanghai and buy muskets and powder for the Taiping forces, and to deliver four letters, to the English, French, American, and Dutch consuls. If he tries to evade the Taiping order, they will behead him when they enter Shanghai, for they will be sure to recognize him. The message for Lambert to deliver is blunt:

They said that if the French or English attempted to resist them when they attacked Shanghae, they would cut off the heads of all foreigners they could get hold of, and stop all the tea and silk trade; that if French and English did not interfere with them, all white men might go over all the country, and trade.

Lambert estimates the Taiping troops in the area where he was held captive at around forty thousand. They seem poorly armed—perhaps one in ten has a musket—but they have established “a regular iron-foundry,” where they are casting the barrels for large guns.5

The information acts as a catalyst for the already nervous foreign community. The Shanghai land defenses are further strengthened by “zigzag redoubts” and gun emplacements that ring the foreign concession areas, manned by a force of four thousand troops, and with eight British warships now anchored off the Shanghai Bund. In the gun emplacements—twelve feet high, built with eight-by-eight-inch beams of Singapore hardwood, to be replaced by hewn stone at a later date when time allows—the allied troops mount swivel guns capable of firing 32-pounder shells. To prevent accidental explosions, all spare munitions are to be stored in an old hulk, moored out in the river. For these and the other necessary defensive measures, the foreign community pledges eighty-six thousand taels of its own money.6

The British “Shanghai Land-renters Association” meetings that assemble at the British consulate are attended by from thirty to forty-five wealthy merchants. Even on the eve of possible annihilation their plans for defending the city are intermeshed with shrewd schemes to make their investments pay. The defensive ditches, for instance, can serve double duty as drainage canals, so that the Chinese owners of the land will be happy to help defray the costs. Making their concession area a “city of refuge” for the wealthier of the fleeing Chinese has not only led to satisfactorily high rents but encouraged the Chinese “better class” to “subscribe freely towards the expense of the blockhouses.” The blockhouses in turn will have excellent value as long-range investments, for they can always be used “in case of a riot, [to] keep the mob in check.”7

One man at the meeting of January 15, 1862, Mr. J. C. Sillar, suggests that the British “enter into friendly communication with the Tae-ping leaders,” and hand over the Chinese city to them, thus enabling “men who printed the Bible” to take over “the idolatrous native city,” and “the city to change rulers amicably.” Thus would the British not only purge themselves of a “national sin” but be able to prevent panic and terror among the Chinese refugees now in the foreign settlements—Mr. Sillar dramatically estimates the total of refugees to be 700,000—who would otherwise “rush down the streets in hundreds and thousands, and drown themselves in the river . . . while the streets would be choked up with the bodies of those trampled under foot.” But Mr. Sillar can get no one to second his motion, and a missionary’s response that now is the time “for prompt and decisive action against the Tae-pings” is “received with acclamation.”8

What nobody, Chinese or foreign, has figured into the careful calculations is the weather. The snow starts to fall on January 26, 1862, and it continues, steadily and unrelentingly, for fifty-eight hours, leaving at least thirty inches on the ground and on the roof tops, and drifts of infinitely greater depth wherever the wind can carry them. As the snow ceases, the hard frosts begin, and the thermometer slowly drops. By January 30, the temperature is down to ten degrees on the Fahrenheit scale. For three weeks the countryside remains buried in what the Shanghai weather report in the North China Herald calls a weather pattern “unprecedented in the meteorological annals of Shanghai for its severity and the low range of the thermometer.”9

The snow is a disaster for the Taiping forces, which lack adequate winter clothing, and can neither force their way across country nor break the ice that blocks the river. “We could not move,” General Li later laconically explains.10

With their momentum checked by the weather in the crucial early months of 1862, the Taiping forces fail to break through the strengthened defenses of Shanghai, whether to occupy the Chinese city or to subdue the foreigners themselves. And seizing the opportunity offered by the absent Taiping armies, in the late spring of 1862 Qing troops advance downriver from Anqing, led by the brother of Zeng Guofan, and capture a strategic base at the foot of Yuhua Hill between the Yangzi River shore and the south gate of Nanjing city itself. Abandoning the attempt to take Shanghai, Li Xiucheng and his troops exhaust their strength throughout the autumn of 1862 in assaults against the new Qing stockades and earthworks in their own backyard, but despite numerous sorties, and attempts to undermine the fortifications, all are unsuccessful.11

Grim as conditions are for the Taiping troops, their sufferings hardly compare with those of the masses of refugees and homeless villagers who wander in the area, displaced again and again by fighting that seems to have no end. These farmers and small-town dwellers of the Yangzi delta have now to contend with at least eight different kinds of troops who march and countermarch around their former homes. There are the Taiping field armies themselves, secret-society or other irregular armies loosely affiliated with the Taiping, independent gangs of river pirates or land-based marauders, the local militias and peasant defenders of rural communities, the large Qing armies recruited by provincial leaders like Zeng Guofan and his brothers, Qing regular forces commanded by the officials of Jiangsu province, Western mercenaries hired by the Qing authorities and currently commanded by the American Frederick Ward, and regular military or naval forces commanded by the British, led by Admiral Hope and Brigadier General Staveley.

For more than a year now, foreigners and Chinese traveling the roads and creeks from Shanghai through Suzhou toward the Yangzi, or even to the walls of Nanjing itself, have grown almost accustomed to a range of somber sights. Across a fifty-mile swath of land one might see almost every house destroyed, wantonly burned by one side or the other, or stripped of its doors and roof beams. That wood then serves either as fuel for the troops, or as makeshift supports for temporary bridges across the myriad canals and creeks, or to shore up the defensive ramparts of some short-lived garrison stockade, erected around villages where every man and boy has been pressed into service by one army or another, and the women carried off, where “human bones lie bleaching among cannon balls” and only the elderly are left to pick among the debris.12 In what is left of these communities, “the houses are in ruins; streets are filled with filth; human bodies are left to decay in the open places or thrown into pools and cisterns there to rot.” On many riverbanks, sometimes for tens of miles, every hut or house is gutted and the people sleep as best they may under rough shelters of mats or reeds.13

Anything that can be used for fuel, whether wood or straw, cotton stalks or reeds, has doubled or tripled in price. Villagers stand along the banks of the creeks, holding out small baskets of produce—eggs, or oranges, or bits of pork—but they are “principally old people, with countenances showing their suffering and despair.”14 Other villagers, encountered on the way, have the four characters “Heavenly Kingdom of Great Peace” tattooed deeply into their faces, proof that they have fled from combat and been recaptured by some Taiping general, and thus been warned not to stray again. Some have scarred and pitted cheeks, where they have tried to cut the same words out with a knife.15

Refugees pass by the travelers, some in small groups, others in crowds of as many as 350 people, men and women, old and young, children and the lame, some carrying their possessions, some flags or spears, some empty-handed. Western missionaries traveling by road or track walk through deserted villages where only animals pick among the ruins and the bodies lie scattered by the road. Those traveling by water find at times that their boats have to push their way slowly through the bodies of the dead, which float, decomposing, in the channels.16 For one missionary traveling in the country near Suzhou, worn by the sight of human bodies “till my heart was sick,” the image that he knows will haunt his brain the longest is that of the “wasted form” of “a little child which had been starved to death, as it sat propped up in a kind of chair or crib, such as the Chinese use for children who are unable to walk.”17

Even veteran British army officers, used to the sufferings caused by wars around the world, of which they have seen so many, and initially sarcastic about the sentimental China missionaries who they feel are prone to exaggerate the suffering they see around them, end up with very similar views. “In all such places as we had an opportunity of visiting,” writes Garnet Wolseley, quartermaster general on the British expeditionary force, “the distress and misery of the inhabitants were beyond description. Large families were crowded together into low, small, tent-shaped wigwams, constructed of reeds, through the thin sides of which the cold wind whistled at every blast from the biting north. The denizens were clothed in rags of the most loathsome kind, and huddled together for the sake of warmth. The old looked cast down and unable to work from weakness, whilst that eager expression peculiar to starvation, never to be forgotten by those who have once witnessed it, was visible upon the emaciated features of the little children.”18

Yet life goes on as people make their adjustments to the reality around them. One Western observer, out with a scouting party in the countryside a day or two after the snow has stopped, steps carefully around the corpse of a Chinese man with a spear driven clear through his skull, and finds himself on a path worn by villagers’ feet through the deep drifts of snow. At the end of the track, a group of villagers have gathered, and are brewing tea amidst the ruins of their still smoldering homes. They are celebrating the dawning of the Chinese New Year, which falls the following day, according to the lunar calendar.19

Many of the Chinese refugees gravitate toward the city of Shanghai, their pace dictated by the prevalence of rumors concerning the nearness of Taiping or other troops: sometimes they “rushed pell-mell along the roads and through the streets like a herd of stricken deer,” at other times “trudging along with their scanty bundles of food and apparel, fear depicted in their countenances.”20 Alarmed at the possibilities of infiltration by squads of disguised Taiping troops among the refugees—a technique used by the Taiping in their recent capture of Hangzhou and many other towns—the Chinese authorities order the gates of the Chinese city closed against them. The promenade, or “bund,” in the foreign areas is crammed, and, the danger of famine and disease rising, the foreigners take steps to quarantine their areas of control. The sepoy troops on the canals receive orders to raise the drawbridges, and the foreign police enforce a curfew forbidding all Chinese to be on the streets after eight in the evening.21 Foreigners have a password they must use if stopped by patrols, and Chinese with a proven right to residence are issued “pass tickets.” All Chinese found at night without these tickets are arrested and evicted from the foreign-controlled areas.22

Captain Charles Gordon of the Royal Engineers, assigned to see to the defenses of Shanghai by the commanding British officer, General Staveley, is under no illusions about the volatility of the situation. He plans his defensive emplacements, redoubts, and ditches so that the British may be protected as well from attack by the Taiping outside the fortifications as from the Chinese residents or refugees within—“a contingency not unlikely to occur considering the disaffected state of some of the inhabitants.”23 British scouting parties can see the flames of burning villages and the flags and troops in the Taiping camps. Surprising a Taiping looting party after the snow has melted, they are struck by the mundane needs of the Taiping troops, marching under their heavy loads of rice, peas and barley, cooking pots, beds and clothing, and driving pigs and goats ahead of them with their spears.24

Even by the summer of 1862 things have grown no better. The British consul reports, “We are once more overrun with refugees, and this time in greater numbers than ever. They are actually camping out on the bund in front of the house, and on the roads near the stone bridge. It is frightful to see the numbers of women, aged and children, lying and living out in the open air, and not over abundantly supplied with food.”25 Those country dwellers rendered destitute by the endless raids live in abject misery in Shanghai, if they ever manage to reach its walls. One shocked Westerner, signing himself simply “Humanitas,” writes of stumbling into one such camp of Chinese refugees in the summer of 1862, after Li Xiucheng’s latest assault on the city has been repulsed. The refugees are crammed into half a dozen bamboo huts off Hanbury’s Road, all “emaciated and wretched in appearance” and some “dying of starvation and disease,” lying on mud floors that flood with every rise in the tidal flow of the river. The living are mixed in with corpses “in all stages of decay,” sometimes blending life and death in one family scene, as in the case of one still living mother, lying on the floor too weak to rise, her two dead and naked children “covered with slush and mud” lying by her side. Such living skeletons are fed only by an erratic system of donated “rice tickets,” to buy more of which “Humanitas” appeals to the Shanghai residents to donate $500, of which he promises to provide one-third.26 As the cold at the end of 1862 ushers in a new winter, all foreigners going to watch the plays at the Chinese theater are asked to give the equivalent of their admission money “to provide food for the Chinese starving poor.”27

It is just after the great snowfall of 1862 that the Westerners’ dogs start disappearing. A black retriever is the first to go, in February, taken from the hospital area.28 “Teazer” is next, a light-brown long-legged bull mastiff with a stumpy tail and black muzzle.29 Then “Smut” vanishes, a black-and-tan bull terrier from the HMS Urgent, followed by two dogs together—both bitches—one a small white-and-black “Japanese,” one a white long-haired “Pekinese” with black ears, called Chin-Chin, almost ready to bear her puppies.30 General Staveley’s dog, a “liver and white pointer” with his name in Chinese characters on the chain collar around his neck, is lost on August 8.31 The brass-collared “Goc,” large and white, with black spots, disappears on August 15, the day “Humanitas” stumbles upon the dead and dying refugees, and shortly thereafter the first New foundland to go, “Sailor,” recently cropped, is taken from the London Missionary Society compound.32 Then, as winter returns again at the close of 1862, it is hard to list them all, the other Newfoundlands and setters, the bulldogs, pointers, spaniels, scotties: “Bull” and “Die,” “Bounce” and “Tie,” “Punch” and “Rover,” “Beechy,” “Toby,” “Mus,” and “Griffin,” “Towzer,” “Nero,” “Bill.”33

The very number of the vanished pets acts as a kind of index to the miseries of the countryside at large. In these endlessly fought-over areas along the Yangzi River, the once vaunted land system of the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom has now become a matter of extracting what grain one can, through levies, gifts, or confiscations. In some of the fertile delta lands to the east, the Taiping are still viewed as liberators by disgruntled peasants, who are glad to see their landlords flee, and willingly pay the Taiping from their resources in lieu of rent.34 But in many areas, after 1861, it is the peasants themselves who form defensive militias to drive the Taiping out, invoking their own gods and fostering their own military champions to keep the “long-hairs” at bay.35 Taiping officers on campaign suffer major losses when bridges they relied on for escape routes are secretly cut by local peasants, leaving their soldiers cornered on some riverbank or creek as the Qing advance. Furious crowds of local villagers, armed with primitive weapons, surround the Taiping troops and make them fear for their lives. Local villagers also stop Taiping convoys of supplies and cash, outnumbering the transporters, and making off with vital resources needed in the bitterly fought campaigns.36

To the Western troops and merchants in Shanghai, on the other hand, the snowstorm, though uncomfortable, is seen as an act of “providence,” and the blow to the Taiping forces is accepted as a blessing, even if the patrolling Western vessels along the smaller creeks are hindered in their work by the ice and snow. For those Westerners with experience of traveling in the last few years through Taiping terrain, much that once seemed colorful or bold has lost its luster and allure. Taiping clothes appear now not as dramatic and original but as “tawdry harlequin garb,” a “burlesque costume.”37 The newly enfeoffed Taiping kings present “a drowsy dissipated appearance,” in their “mountebank yellow dresses and tinsel crowns.”38 The streets of Nanjing are crammed with “a wonderful number of good-looking young women” in gorgeous silks, but these are the captured women from Suzhou, prisoners of war who often try to run away; and though huge new palaces are rising in the city they “stand conspicuous among the ruins,” each strip of cleared land surrounded by evicted families.39 Similarly, the playful Taiping boys who once seemed charming to the Westerners are seen now as sinister, or as starvelings. The very silence of the city, once a harbinger of peace, seems now heavy with the menace of impending doom.40 And the vaunted Taiping warriors, on closer glance, are “dirty and diseased,” displaying, underneath their glittering silks, arms jingling with golden bracelets that cannot hide the scabs of running sores.41

Even Joseph Edkins, intrigued by his religious arguments with the Heavenly King and eager to be one of those missionaries sought to bring new life to Taiping religion, slowly and reluctantly gives up his dream of settling in the town of Nanjing that once had seemed to him so beautiful. For Edkins has a young wife of twenty-three, and he worries over her safety in the insurgents’ city should he be away preaching. He grieves too over the Taiping’s practice of forbidding day laborers from entering the city, the low-quality housing offered to him and his wife, and the terrible unhealthiness of the climate and foulness of the water. He notices that even the Chinese who have lived in the city for years still choose to mix large doses of medicinal drugs into their water before they dare to drink it. Ultimately, for the young couple, “duty calls to Nankin, while inclination says the north,” and inclination wins.42

After the departures of Roberts and Edkins, there are no Westerners left in the Heavenly Capital except for a few mercenaries still held to the Taiping cause by love or money. One last Protestant missionary travels there in the late spring of 1863, and he is wary rather than hostile in the brief report he gives to the Hong Kong press. Nanjing seems to him still fairly prosperous; some crops are growing within the walls. He is granted an interview with the Shield King, Hong Rengan, whom he finds baffled by the foreigners’ unfriendly behavior, and threatening to wreck all foreign trade if they send armed forces against Nanjing.43 As to Hong Rengan himself, for several years the courteous mediator with the Westerners, he claims merely that Roberts’ flight from Nanjing is due to “some slight misunderstanding.”44 But either that misunderstanding or something else unexplained is sufficient for Hong Rengan to forfeit the high office and trust that Hong Xiuquan has given him since he first arrived. Instead of being confirmed in his position as the modernizer of the Heavenly Kingdom, and joint director of the Taiping armies, he is told to supervise the education of the Young Monarch, Tiangui, an assignment that leaves him so “filled with anxiety” that he gives “way to tears.”45

The constant fighting in the area around Shanghai and the growing isolation of Nanjing do not mean that trade has fallen off for the foreigners. Indeed since the revised commercial and diplomatic treaty settlements of 1860 with the Qing, and the reopening of trade by riverboat and steamer with the inland Yangzi city of Hankou, Shanghai is the booming center of the trade in silk and opium, munitions, food and tea. So many ships are moored along the bund and in the lower reaches of the Huangpu River that a special daily broadsheet—the Daily Shipping and Commercial News—is published to supplement the weekly North China Herald.46 By September 1862, another supplement begins, published in Chinese to cover Chinese trade, “The Chinese Shipping List and Advertiser,” to appear on Tuesdays, Thursdays, and Saturdays.47

It is true that the American presence in Shanghai has somewhat fallen off, for the “East India Squadron” of the United States has been dissolved in 1861, as news of the Civil War at home reaches the ships of the China station. Though the commanding officer, Flag Officer Cornelius Stribling, refuses to accept the resignations offered by those of his officers who support the Confederacy until he receives confirmation from the Navy Department, he himself is abruptly relieved of his command on orders from Washington because his native state is South Carolina. The serviceable American vessels are ordered to steam or sail at once for home. Thereafter, for three years, the only major sign of the American naval presence comes from the largely imagined threats of Confederate “privateers.”48 But as if in compensation, in June 1862 the first Japanese ship to dock in Shanghai, the Zen Sai Maroo—formerly the British ship Armistice, bought by the Japanese government for $34,000—arrives “with a cargo of sundries,” and bringing with her to Shanghai “a sort of Commission charged with the duty of acquiring all kinds of information, commercial, statistical, and geographical.”49

The foreigners now pouring into Shanghai span the whole range from affluence to desperation, and the city adapts swiftly to receive them. For the wealthiest, there is the Hotel de l’Europe, open now for “tiffin,” and the French concession offers fine rooms in the new Hotel des Messageries Imperiales.50 A new luxury hotel, the Clarendon, opens in July 1863, to supplement the old Imperial Hotel, where as a legacy from the departed Americans, there is now a brand-new tenpin bowling alley.51 A recently departed visitor is honored in the newly named Elgin Arms, headquarters for the weekly assemblies of the North China Pigeon Club.52 The Astor has a new billiard room, and it is perhaps a sign of the changing values in the town that the Oriental Billiard Saloon has taken over the former Shanghai library on the corner of Church Street and Mission Road, where it also sells wines and spirits.53 Miller’s Hotel, going everyone else one better, offers both a bowling alley and a billiard room. While for those who want a calmer life, just off the Yang-king-pang Creek that separates the British from the Chinese city, the old brig Sea Horse has been converted into the Sea Horse Floating Hotel, and offers a “quiet and comfortable home” for permanent or transient boarders, at decent rates of sixty dollars a month, with one dollar extra for breakfast or dinner, though all board must be paid “invariably in advance.”54

The city’s amenities expand to respond to these newest needs and tastes. Fogg and Co. is offering for sale six sets of tenpins and bowling balls, and six sets of billiard balls and cues, complete with extra tips and chalk. Two “photographic portrait rooms” are established in the town, which as well as taking pictures of the locals offer “sceneograms” of troops in the recent battles. 55 “Professor Risley and the most Numerous and Talented Company of Artistes with Ten unrivalled Horses” performs in the town, while not only has the racecourse been expanded, but a consignment of twenty Arab racehorses arrives from Sydney in Australia, along with mares and geldings to serve as carriage horses.56

From the ships that cram the harbor come, as well, a steady stream of deserters, ne’er-do-wells, and drifters. The police station logbooks are full of the harassments, the delinquencies, and the random violent acts of those they list as “distressed subjects,” or as “vagrants.” Some of the crimes are often pathetic in their smallness, hinting at the real misery of the offenders: at various times Westerners are booked for stealing a loaf of bread, a piece of meat, some peaches, or some pairs of socks, all from Chinese vendors.57 But others show different levels of violence, from drunken assaults and attempted rape of both Chinese and Western women in the town to the abduction of Chinese boys.58 There are stabbings and murders in the run-down rooming houses where the derelicts congregate, such as those run for the “Manilamen” in Bamboo Town, or in Mr. Harvey’s Grog Shop in Hong-que, in the “low public house in the French Concession” known as the Liverpool Arms, or in Allen’s Mariner’s Home, across the river on the Putong side, effectively beyond the range of either Western or Chinese law.59

The British consul attempts to control both the pleasures and the violence by issuing annual licenses to the “Houses of Entertainment” in the Hong-que district, but there are constant setbacks and deceptions: Police Sergeant Mason, for example, turns out to be a secret partner in a hotel in Hong-que where many of the crimes occur, and Police Constable Hayden has for months been “receiving money from keepers of gambling houses without authority.”60 Indeed around a quarter of the cases prosecuted in Shanghai during 1863 concern the police constables themselves, charged with being absent from duty, asleep at their posts, drunk and incapable, disorderly, or with committing assault and battery on the populace they are meant to be protecting. In many cases the constables are repeat offenders: there is a seventh arrest for drunkenness for Police Constable 4, a ninth for PC 118, and a fourteenth for PC 32.61 As the chief inspector of police points out plaintively to the Shanghai Municipal Council in early 1863, he has only enough reliable men to patrol the north-south streets effectively. Fully aware of this, the local rowdies and criminals concentrate their robberies on the streets that run from east to west.62

Most difficult to control are the cases of those who deal in weapons with the Taiping. The numbers of cases grow steadily in 1863: “P. Lodie, aged 31, Scotland, resident Shanghai, selling arms to rebels.” “W. Hardy and others, having charge of a cargo boat with arms and rebel passes.” “H. Stokes, alias Beechy, and others, Breach of Neutrality.”63 The materials of war are everywhere in the city, and there is apparently no way to contain them. Some of the arms travel huge distances, from Hong Kong and even from Singapore, where at least three thousand cannon a year enter the international arms market, and the marine stores all sell both artillery and small arms.64 The municipal council itself contributes to some of the spread, despite its protestations, by selling off all its old muskets and percussion caps to raise money when a new batch of Enfield rifles is shipped in for the volunteer forces.65 The British army also contributes through General Staveley, who sells off the “arms and accoutrements” of the Twenty-second Punjab Native Infantry and the Fifth Bengal Native Infantry to ease the logistics of their passage when they are posted home to India.66

The Westerners in Shanghai carry arms as a matter of course; the inventories of their possessions often show shotguns, rifles, and revolvers, along with the brandy and cigars, the furniture, crockery, dogs, and bedding.67 The British interpreter Thomas Taylor Meadows, an adventurous but pacific soul who remains one of the Taiping’s most forceful backers long after most other Westerners have turned against them, casually describes the personal armory he takes on his trips upriver as consisting of “a Jacob’s single-barrelled 32 gauge rifle; two long single-barrelled shoulder wild-fowl guns (Colonel Hawker’s kind); two double-barrelled shot guns with longish barrels; two double-barrelled shot guns of the usual length; and, lastly, a pair of holster and a pair of belt revolvers of the London Armory Company (Adam’s patent).”68

Gunrunners and arms dealers operate on an ever-larger scale, as shown by the register of arms sold to the Taiping in April 1862 by an American firm “well known for their dealings with the rebels”: 2,783 muskets, 66 carbines, 4 rifles, 895 field pieces of artillery, 484 powder kegs, 10,947 pounds of gunpowder, 18,000 cartridges, and 3,113,500 percussion caps. The dealers—in this case four Americans, their linguist, and eleven coolies, operating two boats—carry passports valid “by land or water” anywhere in Taiping territory, signed by an officer of the Loyal King, Li Xiucheng, and dated “12th year of 4th moon, and 2nd day, of the Kingdom of Universal Peace of God the Father, God the Son, and God the Heavenly King.”69 Less than two months later, in a double raid, British police seize a boat, manned partly by Europeans, that is conveying an additional 1,550,000 percussion caps and forty-eight cases of muskets to the Taiping, while the French stop another boat that has around 5,000 “stands of arms.” Significantly, the French also impound “the implements for manufacturing them,” and a Shanghai newspaper notes that many of these arms are manufactured “under our very eyes, on the opposite bank of the Wong-poo River.”70

Such sales of equipment are important to the Taiping. A Western observer in Nanjing in the summer of 1862 notes that “the city possesses some men of ingenuity,” and the guns made there—including heavy cannon—are far better than those manufactured by the Qing.71 Boxes of percussion caps are used instead of currency by foreign traders dealing with the Taiping.72 Other arms shipments intercepted include 300 pounds of gunpowder marked as “kegs of salted butter,” while percussion caps are shipped as “screws” or even as “religious tracts,” and rifles as “umbrellas.”73 The bulk of these foreign gunrunners and illicit traders are British or American, but some are Belgian, Swedish, Prussian, or Italian.74 The Taiping also capture Western arms in combat, including gunpowder, muskets, and even a 12-pounder howitzer, and add these windfalls to their own stockpiles at Nanjing and elsewhere.75

It is in early 1863 that Li Xiucheng attempts to launch a new campaign to the west, on the north bank of the Yangzi, in Anhui province, to distract Zeng Guofan and his brother from the Nanjing siege. Within a few weeks Li’s troops, which have set out so boldly, are bogged down in mud and driving rain. The areas on the north bank of the Yangzi they campaign in have been fought over so often that no grain supplies are left, and the new crops have not yet had a chance to ripen. Many of Li’s troops fall sick; some of them eat grass; others die of hunger. The Qing garrisons in Anhui, made canny by past experience, simply sit tight behind their defenses and refuse to be lured out in combat.76 Like Li’s Shanghai ventures, the new campaign is a brave but costly failure, which deflects tens of thousands of Taiping troops and new recruits from either relieving the siege of Nanjing directly or strengthening the cities between Suzhou and Shanghai. These fall one by one to the inexorable and well-armed British and French military and naval forces stationed in Shanghai, working in conjunction with Qing troops and the Ever-Victorious Army, led first by Frederick Ward of Salem, Massachusetts, and then by Charles Gordon.77

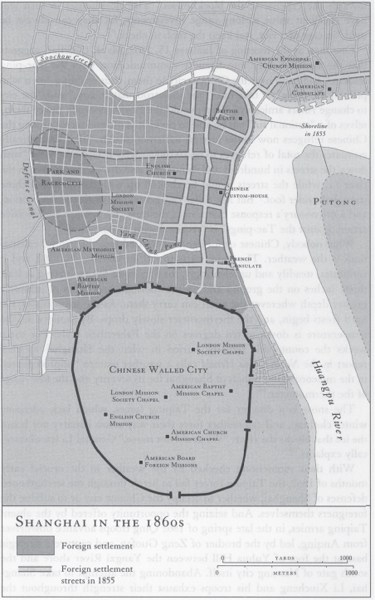

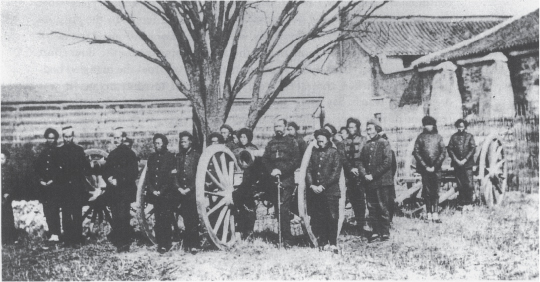

In 1860 the Taiping threat to Shanghai prompted the formation of a foreign mercenary defense force, which evolved into the Western-officered force of Chinese troops called the Ever-Victorious Army. Trained in Western drill and tactics, well-armed and neatly uniformed, the force was led in turn by the American Frederick Ward and the British officers John Holland and Charles Gordon. A similar type of force, commanded by French officers, was named the Ever-Triumphant Army. These armies, though at times erratic in performance, played a significant role in establishing a defensive perimeter around Shanghai, and later in helping the Qing suppress the Taiping in East China. The first photographs of combat troops in China were made during Lord Elgin’s assaults on the north in 1860. These two photographs of the Sino-foreign forces in the Shanghai region probably date from 1863 or 1864.

In May 1863 Li abandons the Western campaign as a failure, and hurries back down the north bank of the Yangzi River to Nanjing on the urgent orders of the Heavenly King. He is met, as he attempts to cross the river, by the Qing forces, now much strengthened and armed with Western implements of war. In Li Xiucheng’s own words, “It was just at the time when the Yangzi was in spate; the roads had been destroyed by the floods, and there was no means of advancing. . . . The army was in disorder. Combat officers and troops, and the horses, were first taken across the river in boats. The crossing was almost completed, but some old and very young, and horses which refused to embark, were left on the river bank. Jiufu zhou was flooded and the soldiers had nowhere to lodge. Even if they had rice, there was no fuel to cook with, and a great many died of hunger. Just at this time, Zeng Guoquan sent river troops to attack.”78 The resulting battle, as described by a Western mercenary still loyal to the Taiping cause, is catastrophic:

Even when [the Taiping] had arrived within sight of their capital, the sufferings of the unfortunate people were not completed until they had endured much more loss by the assaults of the enemy. Upon the arrival of the famished and emaciated troops at the brink of the river, they were saluted with one continuous cannonade from the gunboats that now found ample opportunities of slaughtering them as they crowded the bank for a distance of nearly two miles. With incredible fortitude they maintained their position, and did not flinch backward by the least perceptible movement; and, in the face of the terrible fire poured into their dense masses at point-blank range (mostly from English guns), proceeded to the work of embarkation as steadily as their weakened condition would permit. . . .

The fearful sights that met my gaze upon every part of the shore I shall never forget. Very many of the weakest men, totally unable to assist themselves further, were left to die within sight of the goal for which they had striven so hard and suffered so greatly, their number being so large that their comrades were not sufficient to help, or get them over the river in the presence of the enemy. The horrible “thud” of the cannon shot crashing continuously among the living skeletons, so densely packed at places that they were swept off by the river, into which they were forced by the pressure from behind; the perfect immobility with which they confronted the death hurled upon them from more than a thousand gunboats; and the slow effort the exhausted survivors made to extricate themselves from the mangled bodies of their stricken comrades, were scenes awful to contemplate. It was dreadful to watch day after day during the time occupied in getting the remnant of that once splendid army across the river, with but little means to succour them, the lanes cut through the helpless multitude on the beach by the merciless fire of the enemy; all so passively endured.79

Once again, Hong Xiuquan has no specific words for General Li, neither of solace nor of encouragement. Nor has Hong himself received such words for some time now, not from his Heavenly Father, nor from his Elder Brother. And if his earthly wife, his mother, or his eldest son have told him of their dreams, Hong has not shared them with his Taiping faithful followers. In the last of the books that he has written, and published in Nanjing, Hong has passed in review all the visits down to earth that Jesus made, and all the messages he conveyed through Xiao Chaogui in the days at Thistle Mountain; he has lived again through the diatribes and promises of God the Father, relayed to Yang Xiuqing and his attendants in the early days in which the city of Nanjing became the Heavenly Capital. He has written out the somber words of Xiao Chaogui, after his wounding in Yongan, that the greater the suffering the more a man can grow, and transcribed with his blunt-nosed brush the final cry of Yang Xiuqing: “The city of your God is set aflame. There is no way to save it.”80 How often the voices from Heaven spoke in those far-off days! Now Heaven has fallen silent.