5. The Impoverishment of the Environment: Women and Children Last*

Vandana Shiva

Ruth Sidel’s book, Women and Children Last1, opens with an account of the sinking of the unsinkable Titanic. Women and children were, indeed, the first to be saved on that dreadful night — that is, those in the first and second class. But the majority of women and children did not survive — they were in the third class.

The state of the global economy is in many ways comparable to the Titanic: glittering and affluent and considered unsinkable. But as Ruth Sidel observed, despite our side-walk cafes, our saunas, our luxury boutiques, we, too, lack lifeboats for everyone when disaster strikes. Like the Titanic, the global economy has too many locked gates, segregated decks and policies ensuring that women and children will be first — not to be saved, but to fall into the abyss of poverty.

Environmental degradation and poverty creation

Development was to have created well-being and affluence for all in the Third World. For some regions, and some people, it has delivered that promise, but for most regions and people, it has instead brought environmental degradation and poverty. Where did the development paradigm go wrong?

Firstly, it focused exclusively on a model of progress derived from Western industrialized economies, on the assumption that Western style progress was possible for all. Development, as the improved well-being of all, was thus equated with the Westernization of economic categories — of human needs, productivity, and growth. Concepts and categories relating to economic development and natural resource utilization that had emerged in the specific context of industrialization and capitalist growth in a centre of colonial power, were raised to the level of universal assumptions and thought to be successfully applicable in the entirely different context of basic-needs satisfaction for the people of the erstwhile colonies — newly independent Third World countries. Yet, as Rosa Luxemburg2 has pointed out, early industrial development in Western Europe necessitated permanent occupation of the colonies by the colonial powers, and the destruction of the local ‘natural economy’. According to Luxemburg, colonialism is a constant, necessary condition for capitalist growth: without colonies, capital accumulation would grind to a halt. ‘Development’ as capital accumulation and the commercialization of the economy for the generation of ‘surplus’ and profits thus involved the reproduction of not only a particular form of wealth creation, but also of the associated creation of poverty and dispossession. A replication of economic development based on commercialization of resource-use for commodity production in the newly independent countries created internal colonies and perpetuated old colonial linkages. Development thus became a continuation of the colonization process; it became an extension of the project of wealth creation in modern, Western patriarchy’s economic vision.

Secondly, development focused exclusively on such financial indicators as GNP (gross national product). What these indicators could not demonstrate was the environmental destruction and the creation of poverty associated with the development process. The problem with measuring economic growth in GNP is that it measures some costs as benefits (for example, pollution control) but fails to fully measure other costs. In GNP calculations clear-felling a natural forest adds to economic growth, even though it leaves behind impoverished ecosystems which can no longer produce biomass or water, and thus also leaves impoverished forest and farming communities.

Thirdly, such indicators as GNP can measure only those activities that take place through the market mechanism, regardless of whether or not such activities are productive, unproductive or destructive.

In the market economy, the organizing principle for natural resource use is maximization of profits and capital accumulation. Nature and human needs are managed through market mechanisms. Natural resources demands are restricted to those registering on the market; the ideology of development is largely based on a notion of bringing all natural resources into the market economy for commodity production. When these resources are already being used by nature to maintain production of renewable resources, and by women for sustenance and livelihood, their diversion to the market economy generates a scarcity condition for ecological stability and creates new forms of poverty for all, especially women and children.

Finally, the conventional paradigm of development perceives poverty only in terms of an absence of Western consumption patterns, or in terms of cash incomes and therefore is unable to grapple with self-provisioning economies, or to include the poverty created by their destruction through development. In a book entitled Poverty: the Wealth of the People,3 an African writer draws a distinction between poverty as subsistence, and poverty as deprivation. It is useful to separate a cultural conception of subsistence living as poverty from the material experience of poverty resulting from dispossession and deprivation. Culturally perceived poverty is not necessarily real material poverty: subsistence economies that satisfy basic needs through self-provisioning are not poor in the sense of deprivation. Yet the ideology of development declares them to be so because they neither participate overwhelmingly in the market economy nor consume commodities produced for and distributed through the market, even though they might be satisfying those basic needs through self-provisioning mechanisms. People are perceived as poor if they eat millets (grown by women) rather than commercially produced and distributed processed foods sold by global agribusiness. They are seen as poor if they live in houses self-built with natural materials like bamboo and mud rather than concrete. They are seen as poor if they wear home-made garments of natural fibre rather than synthetics. Subsistence, as culturally perceived poverty, does not necessarily imply a low material quality of life. On the contrary, millets, for example, are nutritionally superior to processed foods, houses built with local materials rather than concrete are better adapted to the local climate and ecology, natural fibres are generally preferable to synthetic ones — and often more affordable. The cultural perception of prudent subsistence living as poverty has provided legitimization for the development process as a ‘poverty-removal’ project. ‘Development’, as a culturally biased process destroys wholesome and sustainable lifestyles and instead creates real material poverty, or misery, by denying the means of survival through the diversion of resources to resource-intensive commodity production. Cash crop production and food processing, by diverting land and water resources away from sustenance needs deprive increasingly large numbers of people from the means of satisfying their entitlements to food.

The resource base for survival is being increasingly eroded by the demand for resources by the market economy dominated by global forces. The creation of inequality through ecologically disruptive economic activity arises in two ways: first, inequalities in the distribution of privileges and power make for unequal access to natural resources — these include privileges of both a political and economic nature. Second, government policy enables resource intensive production processes to gain access to the raw material that many people, especially from the less privileged economic groups, depend upon for their survival. Consumption of this raw material is determined solely by market forces, unimpeded by any consideration of the social or ecological impact. The costs of resource destruction are externalized and divided unequally among various economic groups in society, but these costs are borne largely by women and those who, lacking the purchasing power to register their demands on the modern production system’s goods and services, provide for their basic material needs directly from nature.

The paradox and crisis of development results from mistakenly identifying culturally perceived poverty with real material poverty, and of mistaking the growth of commodity production as better satisfying basic needs. In fact, however water, soil fertility, and genetic wealth are considerably diminished as a result of the development process. The scarcity of these natural resources, which form the basis of nature’s economy and especially women’s survival economy, is impoverishing women, and all marginalized peoples to an unprecedented extent. The source of this impoverishment is the market economy, which has absorbed these resources in the pursuit of commodity production.

Impoverishment of women, children and the environment

The UN Decade for Women was based on the assumption that the improvement of women’s economic position would automatically flow from an expansion and diffusion of the development process. By the end of the Decade, however, it was becoming clear that development itself was the problem. Women’s increasing underdevelopment was not due to insufficient and inadequate ‘participation’ in ‘development’ rather, it was due to their enforced but asymmetric participation whereby they bore the costs but were excluded from the benefits. Development and dispossession augmented the colonial processes of ecological degradation and the loss of political control over nature’s sustenance base. Economic growth was a new colonialism, draining resources away from those who most needed them. But now, it was not the old colonial powers but the new national elites that masterminded the exploitation on grounds of ‘national interest’ and growing GNPs, and it was accomplished by more powerful technologies of appropriation and destruction.

Ester Boserup4 has documented how women’s impoverishment increased during colonial rule; those rulers who had for centuries subjugated and reduced their own women to the status of de-skilled, de-intellectualized appendages, discriminated against the women of the colonies on access to land, technology and employment. The economic and political processes of colonial underdevelopment were clear manifestations of modern Western patriarchy, and while large numbers of men as well as women were impoverished by these processes, women tended to be the greater losers. The privatization of land for revenue generation affected women more seriously, eroding their traditional land-use rights. The expansion of cash crops undermined food production, and when men migrated or were conscripted into forced labour by the colonizers women were often left with meagre resources to feed and care for their families. As a collective document by women activists, organizers and researchers stated at the end of the UN Decade for Women:

The almost uniform conclusion of the Decade’s research is that with a few exceptions, women’s relative access to economic resources, incomes and employment has worsened, their burden of work has increased, and their relative and even absolute health, nutritional and educational status has declined.5

Women’s role in the regeneration of human life and the provisioning of sustenance has meant that the destructive impact on women and the environment extends into a negative impact on the status of children.

The exclusive focus on incomes and cash-flows as measured in GNP has meant that the web of life around women, children and the environment is excluded from central concern. The status of women and children and the state of the environment have never functioned as ‘indicators’ of development. This exclusion is achieved by rendering invisible two kinds of processes. Firstly, nature’s, women’s and children’s contribution to the growth of the market economy is neglected and denied. Dominant economic theories assign no value to tasks carried out at subsistence and domestic levels. These theories are unable to encompass the majority in the world — women and children — who are statistically ‘invisible’. Secondly the negative impact of economic development and growth on women, children and environment goes largely unrecognized and unrecorded. Both these factors lead to impoverishment.

Among the hidden costs generated by destructive development are the new burdens created by ecological devastation, costs that are invariably heavier for women, in both the North and South. It is hardly surprising, therefore, that a rising GNP does not necessarily mean that either wealth or welfare increase proportionately. I would argue that GNP is becoming increasingly a measure of how real wealth — the wealth of nature and the life sustaining wealth produced by women — is rapidly decreasing. When commodity production as the prime economic activity is introduced as development, it destroys the potential of nature and women to produce life and goods and services for basic needs. More commodities and more cash mean less life — in nature through ecological destruction and in society through denial of basic needs. Women are devalued, first, because their work co-operates with nature’s processes, and second, because work that satisfies needs and ensures sustenance is devalued in general. More growth in what is maldevelopment has meant less nurturing of life and life support systems.

Nature’s economy — through which environmental regeneration takes place — and the people’s subsistence economy — within which women produce the sustenance for society through ‘invisible’ unpaid work called non-work — are being systematically destroyed to create growth in the market economy. Closely reflecting what I have called the three economies, of nature, people and the market in the Third World context, is Hilkka Pietila’s6 categorization of industrialized economies as: the free economy; the protected sector; and the fettered economy.

The free economy: the non-monetary core of the economy and society, unpaid work for one’s own and family needs, community activities, mutual help and co-operation within the neighbourhood and so on.

The protected sector: production, protected and guided by official means for domestic markets; food, constructions, services, administration, health, schools and culture, and so on.

The fettered economy: large-scale production for export and to compete with imports. The terms dictated by the world market, dependency, vulnerability, compulsive competitiveness and so forth.

For example, in 1980, the proportions of time and money value that went into running each category of the Finnish economy were as follows!

Table 5.1

Time | Money | |

A. The free economy, informal economy | 54% | 35% |

B. Protected sector | 36% | 46% |

C. The fettered economy | 10% | 19% |

In patriarchal economics, B and C are perceived as the primary economy, and A as the secondary economy. In fact as Marilyn Waring7 has documented, national accounts and GNP actually exclude the free economy as lying outside the production boundary. What most economists and politicians call the ‘free’ or ‘open’ economy is seen by women as the ‘fettered’ economy. When the fettered economy becomes ‘poor’ — that is, runs into deficit — it is the free economy that pays to restore it to health. In times of structural adjustment and austerity programmes, cuts in public expenditure generally fall most heavily on the poor. In many cases reduction of the fiscal deficit has been effected by making substantial cuts in social and economic development expenditure, and real wages and consumption decrease considerably.

The poverty trap, created through the vicious cycle of ‘development’, debt, environmental destruction and structural adjustment is most significantly experienced by women and children. Capital flows North to South have been reversed. Ten years ago, a net $40 billion flowed from the Northern hemisphere to the countries of the South. Today in terms of loans, aid, repayment of interest and capital, the South transfers $20 billion a year to the North. If the effective transfer of resources implied in the reduced prices industrialized nations pay for the developing world’s raw materials is taken into account, the annual flow from the poor to the rich countries could amount to $60 billion annually. This economic drain implies a deepening of the crisis of impoverishment of women, children and the environment.

According to UNICEF estimates, in 19888 half-a-million children died as a direct result of debt-related adjustment policies that sustain the North’s economic growth. Poverty, of course, needs to be redefined in the emerging context of the feminization of poverty on the one hand, and the link to environmental impoverishment on the other.

Poverty is not confined to the so-called poor countries; it exists in the world’s wealthiest society. Today, the vast majority of poor people in the US are women and children. According to the Census Bureau, in 1984, 14.4 per cent of all Americans (33.7 million) lived below the poverty line. From 1980 to 1984 the number of poor people increased by four-and-a-half million. For female-headed households in 1984, the poverty rate was 34.5 per cent — five times that for married couples. The poverty rate for white, female-headed families was 27.1 per cent; for black, woman-headed families, 51.7 per cent; and for woman-headed Hispanic families, 53.4 per cent. The impact of women’s poverty on the economic status of children is even more shocking: in 1984, the poverty rate for children under six was 24 per cent, and in the same year, for children living in women-headed households it was 53.9 per cent. Among black children the poverty rate was 46.3 per cent; and for those living in female-headed families, 66.6 per cent. Among Hispanic children 39 per cent were poor, and for those living in female-headed families, the poverty rate was 70.5 per cent.9

Theresa Funiciello, a welfare rights organizer in the US, writes that ‘By almost any honest measure, poverty is the number one killer of children in the U.S.’ (Waring, 1988).

In New York City, 40 per cent of the children (700,000) are living in families that the government classifies deprived as 7,000 children are born addicted to drugs each year, and 12,000 removed to foster homes because of abuse or neglect (Waring 1988).

The first right mentioned in the Convention of the Rights of the Child is the inherent right to life. Denial of this right should be the point of departure for evolving a definition of poverty. It should be based on denial of access to food, water and shelter in the quality and quantity that makes a healthy life possible.

Pure income indicators often do not capture the poverty of life to which the future generations are being condemned, with threats to survival from environmental hazards even in conditions otherwise characterized by ‘affluence’. Poverty has so far been culturally perceived in terms of life styles that do not fit into the categories of Western industrial society. We need to move away from these restricted and biased perceptions to grapple with poverty in terms of threats to a safe and healthy life either due to denial of access to food, water and shelter, or due to lack of protection from hazards in the form of toxic and nuclear threats.

Human scale development can be a beginning of an operational definition of poverty as a denial of vital human needs. At the highest level, the basic needs have been identified as subsistence, protection, affection, understanding, participation, leisure, creation, identity, freedom. These needs are most clearly manifest in a child, and the child can thus become our guide to a humane, just and sustainable social organization, and to a shift away from the destructiveness of what has been construed as ‘development’.10

While producing higher cash flows, patriarchal development has led to deprivation at the level of real human needs. For the child, these deprivations can become life threatening, as the following illustrates.

The food and nutrition crisis

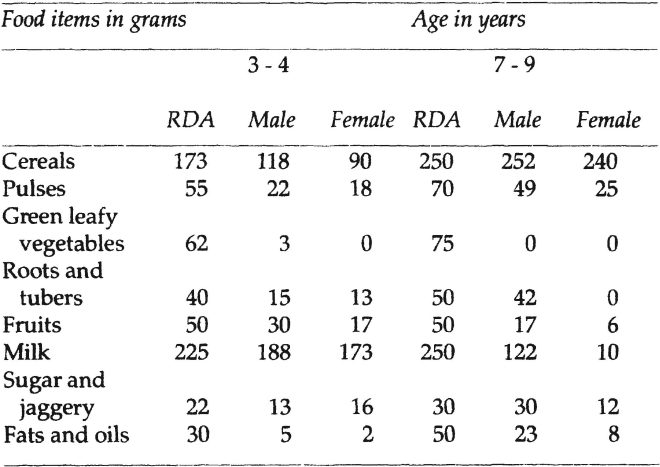

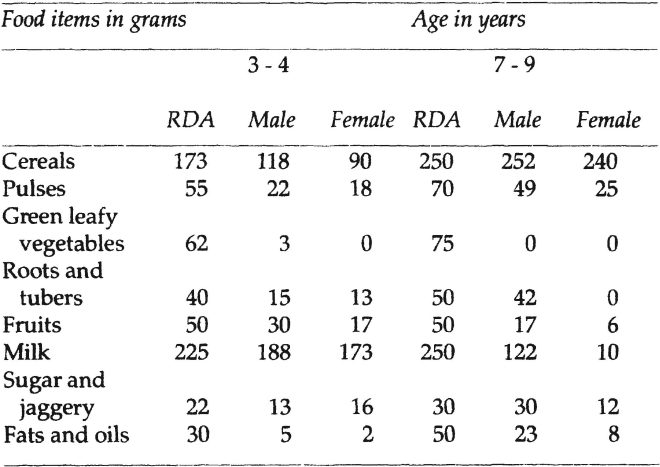

Both traditionally, and in the context of the new poverty, women and children have been treated as marginal to food systems. In terms of nutrition the girl-child is doubly discriminated against in such countries as India (see Table 5.2)11.

The effects of inadequate nourishment of young girls continue into their adulthood and are passed on to the next generation. Complications during pregnancy, premature births and low birth weight babies with little chance of survival result when a mother is undernourished; and a high percentage of deaths during pregnancy and childbirth are directly due to anaemia, and childhood undernourishment is probably an underlying cause.12 Denial of nutritional rights to women and children is the biggest threat to their lives.

Programmes of agricultural ‘development’ often become programmes of hunger generation because fertile land is diverted to grow export crops, small peasants are displaced, and the biological diversity, which provided much of the poor’s food entitlements, is eliminated and replaced by cash crop monocultures, or land-use systems ill-suited to the ecology or to the provision of people’s food entitlements. A permanent food crisis affects more than a 100 million people in Africa; famine is just the tip of a much bigger underlying crisis. Even when Ethiopia is not suffering from famine, 1,000 children are thought to die each day of malnutrition and related illnesses.13

Everywhere in the South, the economic crisis rooted in maldevelopment is leading to an impoverishment of the environment and a threat to the survival of children. It is even possible to quantify the debt mortality effect: over the decade of 1970 to 1980, each additional $10 a year interest payments per capita reflected 0.39 of a year less in life expectancy improvement. This is an average of 387 days of life foregone by every inhabitant of the 73 countries studied in Latin America.14 Nutritional studies carried out in Peru show that in the poorest neighbourhoods of Ijma and surrounding shanty towns, the percentage of undernourished children increased from 24 per cent in 1972 to 28 per cent in 1978 and to 36 per cent in 1983.

Table 5.2

Foods received by male and female children 3-4 and 7-9 years (India)

Source: Devadas, R. and G. Kamalanathan, ‘A Women’s First Decade’, Paper presented at the Women’s NGO Consultation on Equality, Development and Peace, New Delhi, 1985.

In Argentina, according to official sources, in 1986 685,000 children in greater Buenos Aires and a further 385,000 in the province of Buenos Aires did not eat enough to stay alive; together constituting one-third of all children under 14.15

Starvation is endemic in the ultra-poor north-east of Brazil, where it is producing what IBASE (a public interest research group in Brazil) calls a ‘sub-race’ and nutritionists call an epidemic of dwarfism. The children in this area are 16 per cent shorter and weigh 20 per cent less than those of the same age elsewhere in Brazil — who, themselves, are not exactly well-nourished.

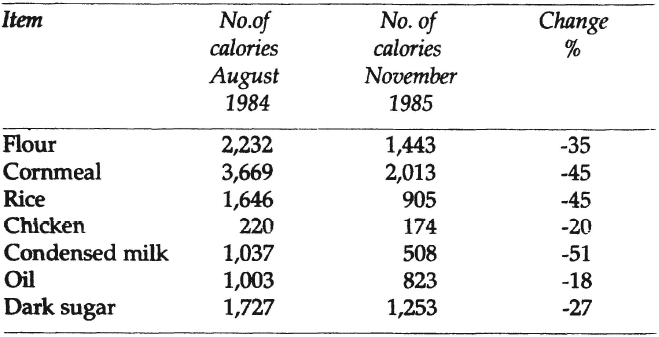

In Jamaica, too, food consumption has decreased as is shown:

Table 5.3

Source: Susan George, A Fate Worse than Debt, 1988, p.188.

As the price of food rose beyond people’s ability to pay, children’s health demonstratively declined. In 1978, fewer than two per cent of children admitted to the Bustamente Children’s Hospital were suffering from malnutrition, and 1.6 per cent from malnutrition-related gastro-enteritis. By 1986, when the full effects of the adjustment policies were being felt, the figures for malnutrition-related admissions had doubled, to almost four per cent; gastro-enteritis admissions were almost five per cent.16

Numerical malnutrition is the most serious health hazard for children, particularly in the developing countries. Surveys in different regions of the world indicate that at any moment an estimated ten million children are suffering from severe malnutrition and a further 200 million are inadequately nourished.17

The increase in nutritional deprivation of children is one result of the same policies that lead to the nutritional deprivation of soils. Agriculture policies which extract surplus to meet export targets and enhance foreign exchange earnings generate that surplus by creating new levels of nutritional impoverishment for women, children and the environment. As Maria Mies has pointed out,18 this concept of surplus has a patriarchal bias because, from the point of view of nature, women and children, it is based not on material surplus produced over and above the requirements of the environment or of the community, it is violently stolen and appropriated from nature (which needs a share of her produce to reproduce herself) and from women (who need a share of nature’s produce to sustain and to ensure the survival of themselves and their children). Malnutrition and deficiency diseases are also caused by the destruction of biodiversity which forms the nutritional base in subsistence communities. For example, bathua is an important green leafy vegetable with very high nutritive value which grows in association with wheat, and when women weed the wheat field they not only contribute to the productivity of wheat but also harvest a rich nutritional source for their families. With the intensive use of chemical fertilizer, however, bathua becomes a major competitor of wheat and has been declared a ‘weed’ to be eliminated by herbicides. Thus, the food cycle is broken; women are deprived of work; children are deprived of a free source of nutrition.

The water crisis

The water crisis contributes to 34.6 per cent of all child deaths in the Third World. Each year, 5,000,000 children die of diarrhoeal diseases.19 The declining availability of water resources, due to their diversion for industry and industrial agriculture and to complex factors related to deforestation, desertification and drought, is a severe threat to children’s health and survival. As access to water decreases, polluted water sources and related health hazards, increase. ‘Development’ in the conventional paradigm implies a more intensive and wasteful use of water — dams and intensive irrigation for green revolution agriculture, water for air-conditioning mushrooming hotels and urban-industrial complexes, water for coolants, as well as pollution due to the dumping of industrial wastes. And as development creates more water demands, the survival needs of children — and adults — for pure and safe water are sacrificed.

Antonia Alcantara, a vendor from a slum outside Mexico City, complains that her tap water is ‘yellow and full of worms’. Even dirty water is in short supply. The demands of Mexico City’s 20 million people have caused the level of the main aquifer to drop as much as 3.4 metres annually.20 Those with access to Mexico City’s water system are usually the wealthy and middle classes. They are, in fact, almost encouraged to be wasteful by subsidies that allow consumers to pay as little as one-tenth the actual cost of water. The poor, on the other hand, are often forced to buy from piperas, entrepreneurs, who fix prices according to demand.

In Delhi, in 1988, 2,000 people (mainly children) died as a result of a cholera epidemic in slum colonies. These colonies had been ‘resettled’ when slums were removed from Delhi to beautify India’s capital. This dispensable population was provided with neither safe drinking water, nor adequate sewage facilities; it was only the children of the poor communities who died of cholera. Across the Yamuna river, the swimming pools had enough chlorinated water to protect the tourists, the diplomats, the elite.21

Toxic hazards

In the late twentieth century it is becoming clear that our scientific systems are totally inadequate to counteract or eliminate the hazards — actual and potential — to which children, in particular, are subjected. Each disaster seems like an experiment, with children as guinea pigs, to teach us more about the effects of deadly substances that are brought into daily production and use. The patriarchal systems would like to maintain silence about these poisonous substances, but as mothers women cannot ignore the threats posed to their children. Children are the most highly sensitive to chemical contamination, the chemical pollution of the environment is therefore most clearly manifested in their ill-health.

In the Love Canal and the Bhopal disasters, children were the worst affected victims. And in both places it is the women who have continued to resist and have refused to be silenced as corporations and state agencies would wish.

Love Canal was a site where, for decades, Hooker Chemical Company had dumped their chemical wastes, over which houses were later built. By the 1970s it was a peaceful middle-class residential area but its residents were unaware of the toxic dumps beneath their houses. Headaches, dizziness, nausea and epilepsy were only a few of the problems afflicting those near the Canal. Liver, kidney, or recurrent urinary strictures abounded. There was also an alarmingly high rate of 56 per cent risk of birth defects, including childhood deafness, and children suffered an unusually high rate of leukemia and other cancers.22 There was a 75 per cent above normal rate of miscarriage, and among 15 pregnancies of Love Canal women, only two resulted in healthy babies.

It was the mothers of children threatened by death and disease who first raised the alarm and who kept the issue alive.

In Japan, the dependence of Minamata Bay’s fishermen and their families on a fish diet had disastrous results as the fish were heavily contaminated with methylmercury, which had been discharged into the Bay over a period of 30 years by the Chissio chemical factory.

In Bhopal, in 1984, the leak from Union Carbide’s pesticide plant led to instant death for thousands. A host of ailments still afflicts many more thousands of those who escaped death. In addition women also suffer from gynaecological complications and menstrual disorders. Damage to the respiratory, reproductive, nervous, musculo-skeletal and immune systems of the gas victims has been documented in epidemiological studies carried out so far. The 1990 report of the Indian Council of Medical Research23 states that the death rate among the affected population is more than double that of the unexposed population. Significantly higher incidences of spontaneous abortions, still-births and infant mortality among the gas victims have also been documented.

A few months after the gas disaster, I had a son. He was alright. After that I had another child in the hospital. But it was not fully formed. It had no legs and no eyes and was born dead. Then another child was born but it died soon after. I had another child just one and a half months back. Its skin looked scalded and only half its head was formed. The other half was filled with water. It was born dead and was white all over. I had a lot of pain two months before I delivered. My legs hurt so much that I couldn’t sit or walk around. I got rashes all over my body. The doctors said that I will be okay after the childbirth, but I still have these problems.24

Nuclear hazards

Hiroshima, Three Mile Island, the Pacific Islands, Chernobyl — each of these nuclear disasters reminds us that the nuclear threat is greater for future generations than for us.

Lijon Eknilang was seven years old at the time of the Bravo test on Bikini Island. She remembers her eyes itching, nausea and being covered by burns. Two days after the test, Lijon and her people were evacuated to the US base on Kwajalein Atoll. For three years they were kept away because Rongelap was too dangerous for life. Lijon’s grandmother died in the 1960s due to thyroid and stomach cancer. Her father died during the nuclear test. Lijon reports that:

I have had seven miscarriages and still-births. Altogether there are eight other women on the island who have given birth to babies that look like blobs of jelly. Some of these things we carry for eight months, nine months, there are no legs, no arms, no head, no nothing. Other children are born who will never recognise this world or their own parents. They just lie there with crooked arms and legs and never speak.25

Every aspect of environmental destruction translates into a severe threat to the life of future generations. Much has been written on the issue of sustainability, as ‘intergenerational equity’, but what is often overlooked is that the issue of justice between generations can only be realized through justice between sexes. Children cannot be put at the centre for concern if their mothers are meantime pushed beyond the margins of care and concern.

Over the past decades, women’s coalitions have been developing survival strategies and fighting against the threat to their children that results from threats to the environment.

Survival strategies of women and children

As survival is more and more threatened by negative development trends, environmental degradation and poverty, women and children develop new ways to cope with the threat.

Today, more than one-third of the households in Africa, Latin America and the developed world are female headed; in Norway the figure is 38 per cent, and in Asia 14 per cent.26 Even where women are not the sole family supporters they are primary supporters in terms of work and energy spent on providing sustenance to the family. For example, in rural areas women and children must walk further to collect the diminishing supplies of firewood and water, in urban areas they must take on more paid outside work. Usually, more time thus spent on working to sustain the family conflicts with the time and energy needed for child care. At times girl children take on part of the mother’s burden: in India, the percentage of female workers below 14 years increased from four to eight per cent. In the 15-19 year age group, the labour force participation rate increased by 17 per cent for females, but declined by eight per cent for males.27 This suggests that more girls are being drawn into the labour force, and more boys are sent to school. This sizeable proportion perhaps explains high female school dropout rates, a conclusion that is supported by the higher levels of illiteracy among female workers, compared with 50 per cent for males. It has been projected that by the year 2001 work participation among 0-14 year old girls will increase by a further 20 per cent and among 15-19 year olds by 30 per cent.28

The International Labour Organization (ILO) has estimated that at the beginning of the 1980s the overall number of children under 15 who were ‘economically active’ was around 50 million; the World Health Organization (WHO) estimates put it at 100 million. There are another 100 million ‘street’ children, without families or homes. These are victims of poverty, underdevelopment, and poor environmental conditions — society’s disposable people — surviving entirely on their own, without any rights, without any voice.

Chipko women of Himalaya have organized to resist the environmental destruction caused by logging.

The Love Canal home owner’s association is another well-known example of young housewives’ persistent action to ensure health security for their families; this has now resulted in the Citizens’ Clearinghouse for Hazardous Waste.

The Bhopal Gas Peedit Mahila Udyog Sangathan, a group of women victims of the Bhopal disaster, has continued to struggle for seven years to obtain justice from Union Carbide Corporation.

Across different contexts, in the North and in the South, in ecologically eroded zones and polluted places, women identify with the interest of the earth and their children in finding solutions to the crisis of survival. Against all odds they attempt to reweave the web which connects their life to the life of their children and the life of the planet. From women’s perspective, sustainability without environmental justice is impossible, and environmental justice is impossible without justice between sexes and generations.

To whom will the future belong? to the women and children who struggle for survival and for environmental security? or to those who treat women, children and the environment as dispensable and disposable? Gandhi proposed a simple test for making decisions in a moment of doubt. ‘Recall the face of the least privileged person you know’, he said, ‘and ask if your action will harm or benefit him/her.’29 This criterion of the ‘last person’ must be extended to the ‘last child’ if we are serious about evolving a code of environmental justice which protects future generations.

Dispensability of the last child: the dominant paradigm

From the viewpoint of governments, intergovernmental agencies, and power elites, the ‘last child’ needs no lifeboat. This view has been explicitly developed by Garrett Hardin in his ‘life-boat ethics’30: the poor, the weak are a ‘surplus’ population, putting an unnecessary burden on the planet’s resources. This view, and the responses and strategies that emerge from it totally ignore the fact that the greatest pressure on the earth’s resources is not from large numbers of poor people but from a small number of the world’s ever-consuming elite.

Ignoring these resource pressures of consumption and destructive technologies, ‘conservation’ plans increasingly push the last child further to the margins of existence. Official strategies, reflecting elite interests, strongly imply that the world would be better off if it could shed its ‘non-productive’ poor through the life-boat strategy. Environmentalism is increasingly used in the rhetoric of manager-technocrats, who see the ecological crises as an opportunity for new investments and profits. The World Bank’s Tropical Action Plan, the Climate Convention, the Montreal Protocol are often viewed as new means of dispossessing the poor to ‘save’ the forests and atmosphere and biological commons for exploitation by the rich and powerful. The victims are transformed into villains in these ecological plans — and women, who have struggled most to protect their children in the face of ecological threats, become the elements who have to be policed to protect the planet.31

‘Population explosions’ have always emerged as images created by modern patriarchy in periods of increasing social and economic polarizations. Malthus32 saw populations exploding at the dawn of the industrial era; between World War I and II certain groups were seen as threatening deterioration of the human genetic stock; post World War II, countries where unrest threatened US access to resources and markets, became known as the ‘population powderkegs’. Today, concern for the survival of the planet has made pollution control appear acceptable and even imperative, in the face of the popularized pictures of the world’s hungry hordes.

What this focus on numbers hides is people’s unequal access to resources and the unequal environmental burden they put on the earth. In global terms, the impact of a drastic decrease of population in the poorest areas of Asia, Africa and Latin America would be immeasurably smaller than a decrease of only five per cent in the ten richest countries at present consumption levels.33

Through population control programmes, women’s bodies are brutally invaded to protect the earth from the threat of overpopulation. Where women’s fertility itself is threatened due to industrial pollution, their interest is put in opposition to the interests of their children. This divide and rule policy seems essential for managing the eco-crisis to the advantage of those who control power and privilege.

The emerging language of manager-technocrats describes women either as the passive ‘environment’ of the child, or the dangerous ‘bomb’ threatening a ‘population explosion’. In either case, women whose lives are inextricably a part of children’s lives have to be managed to protect children and the environment.

The mother’s womb has been called the child’s ‘environment’. Even in the relatively sheltered environment of the mother’s uterus the developing baby is far from completely protected. The mother’s health, so intimately linked to the child’s well-being is reduced to a ‘factor within the foetus’s environment’.

Similar decontextualized views of the womn-child relationship are presented as solutions to managing environmental hazards in the workplace. ‘Foetal protection policies’ are the means by which employers take the focus off their own hazardous production by offering to ‘protect the unborn’ by removing pregnant (or wanting-to-be pregnant) women from hazardous zones.34 In extreme cases, women have consented to sterilization in order to keep their jobs and keep food on the table. More typically, practices include surveillance of women’s menstrual cycles, of waiting for a woman to abort her pregnancy before employing her. As Lin Nelson has stated: ‘It is all too easy to “assume pollution” and accept industrial relocation and obstetrical intervention, but they are responses to the symptoms, not the disease.’35

Grassroots response

Community groups, NGOs, ecology movements and women’s movements begin the reversal of environmental degradation by reversing the trends that push women and children beyond the edge of survival. As mentioned earlier, the Chipko movement in India has been one such response. In Kenya, the Green Belt movement has fostered 1,000 Community Green Belts. In Malaysia, the Sahabal Alain Malaysia (SAM) and Consumer Association of Penang have worked with tribal, peasant, and fishing communities to reverse environmental decline. Tribals’ blockades against logging in Sarawak are another important action in which these organizations have been involved. In Brazil the Acao Democratica Feminina Gaucha (ADFG) has been working on sustainable agriculture, indigenous rights, debt and structural adjustment.

What is distinctive about these popular responses is that they put the last child at the centre of concern, and work out strategies that simultaneously empower women and protect nature. Emerging work on women, health and ecology, such as the dialogue organized by the Research Foundation of India and the Dag Hammarskjold Foundation of Sweden,36 the Planeta Femea at the Global Forum in Rio 199237 are pointing to new directions in which children’s, women’s and nature’s integrity are perceived in wholeness, not fragmentation.

Putting women and children first

In 1987, at the Wilderness Congress, Oren Lyons of the Onondaga Nation said: ‘Take care how you place your moccasins upon the earth, step with care, for the faces of the future generations are looking up from the earth waiting for their turn for life.’38

In the achievements of growing GNPs, increasing capital accumulation, it was the faces of children and future generations that receded from the minds of policy makers in centres of international power. The child had been excluded from concern, and cultures which were child-centred have been destroyed and marginalized. The challenge to the world’s policy makers is to learn from mothers, from tribals and other communities, how to focus decisions on the well-being of children.

Putting women and children first needs above all, a reversal of the logic which has treated women as subordinate because they create life, and men as superior because they destroy it. All past achievements of patriarchy have been based on alienation from life, and have led to the impoverishment of women, children and the environment. If we want to reverse that decline, the creation, not the destruction of life must be seen as the truly human task, and the essence of being human has to be seen in our capacity to recognize, respect and protect the right to life of all the world’s multifarious species.

1. Sidel, Ruth, Women and Children Last. Penguin, New York, 1987.

2. Luxemburg, Rosa, The Accumulation of Capital. Routledge and Kegan Paul, London, 1951.

3. Quoted in R. Bahro, From Red to Green. Verso, London, 1984, p. 211.

4. Boserup, Ester, Women’s Role in Economic Development. Allen and Unwin, London, 1960.

5. DAWN, 1985, Development Crisis and Alternative Visions: Third World Women’s Perspectives. Christian Michelsen Institute, Bergen.

6. Pietila, Hilkka, Tomorrow Begins Today. ICDA/ISIS Workshop, Nairobi, 1985.

7. Waring, Marilyn If Women Counted. Harper & Row, San Francisco, 1988.

8. UNICEF, State of the World’s Children, 1988.

9. Quoted in Marilyn Waring, op. cit. p. 180; and Ruth Sidel, op. cit.

10. Max-Neef, Manfred, Human Scale Development, Development Dialogue. Dag Hammarskjold Foundation, 1989.

11. Chatterjee, Meera, A Report on Indian Women from Birth to Twenty. National Institute of Public Cooperation and Child Development, New Delhi, 1990.

12. Timberlake, Lloyd, Africa in Crisis, Earthscan, London, 1987.

13. Susan George, A Fate Worse than Debt. Food First, San Francisco, 1988.

14. Ibid.

15. Ibid.

16. Ibid.

17. UNICEF, Children and the Environment, 1990.

18. Maria Mies, Patriarchy and Accumulation on a World Scale. Zed Books, London, 1987.

19. UNICEF, op. cit., 1990.

20. Moser, Caroline, Contribution on OECD Workshop on Women and Development. Paris, 1989.

21. Shiva, Mira ‘Environmental Degradation and Subversion of Health’ in Vandana Shiva (ed.) Minding Our Lives: Women from the South and North Reconnect Ecology and Health, Kali for Women, Delhi, 1993.

22. Gibbs, Lois, Love Canal, My Story. State University of New York, Albany, 1982.

23. Bhopal Information and Action Group, Voices of Bhopal. Bhopal, 1990.

24. Ibid.

25. Pacific Women Speak, Women Working for a Nuclear Free and Independent Pacific, 1987.

26. United Nations, World’s Women, 1970-1990.

27. Chatterjee, Meera op. cit.

28. UNICEF, op. cit., 1990.

29. Kothari, Rajni, Vandana Shiva, ‘The Last Child’, Manuscript for United Nations University Programme on Peace and Global Transformation.

30. Hardin, Garrett, in Bioscience, Vol. 24, (1974) p. 561.

31. Shiva, Vandana ‘Forestry Crisis and Forestry Myths: A Critical Review of Tropical Forests: A Call for Action,’ World Rainforest Movement, Penang, 1987.

32. Malthus, in Barbara Duden, ‘Population’, in Wolfgang Sachs (ed) Development Dictionary. Zed Books, London, 1990.

33. UNICEF, op. cit., 1990.

34. Nelson, Lin, ‘The Place of Women in Polluted Places’ in Reweaving the World: The Emergence of Ecofeminism, Irene Diamond and Gloria Orenstein (eds). Sierra Club Books, 1990.

35. Ibid.

36. ‘Women, Health and Ecology,’ proceedings of a Seminar organized by Research Foundation for Science, Technology and Natural Resource Policy, and Dag Hammarskjold Foundation, in Development Dialogue 1992.

37. ‘Planeta Femea’ was the women’s tent in the Global Forum during the UN Conference on Environment and Development, 1992.

38. Lyons, Oren 4th World Wilderness Conference, 11 September 1987, Eugene, Oregon.

*This is an extensively revised version of a background paper presented for the UNCED Workshop ‘Women and Children First’, Geneva, May 1991