Nobody, but nobody writes detective stories like Don Von Elsner. And no other detective but his Jake Winkman gets write-ups in Oswald Jacoby’s bridge columns. But no one else in fiction and very few in real life play bridge the way Jake Winkman does. If you don’t believe it, read on.

Bridge pro Jake Winkman stood at the window of the luxurious suite where Edna Mayberry Mallory had installed him in her imposing Tudor mansion. He fingered his black tie and frowned.

There was nothing wrong with the view. It commanded a sweep of broad marble terrace and a trellised rose garden with curvaceous and inviting pathways that sloped down to the lake, where gentle swells, gray-blue in the twilight, were breaking considerately against a carefully manicured beach. It always seemed a little unreal to him that the rich could contrive to have problems.

Jeanne, the Countess d’Allerez, and Prince Sergio Polensky emerged from the garden to ascend the broad marble steps of the terrace. The Prince had his arm around her and was whispering something, doubtless tender and exotically accented, into her delicate ear. Slim and seductive, the Countess was wearing a gown that featured provocatively little above the waist but billowed enticingly below. It fit perfectly, Jake decided, into the theme of his well-chosen surroundings, but did nothing to erase his frown.

A weekend of bridge and swimming in the rarified atmosphere of conservative Lake Forest was all very well, and he had been a guest here before. The stakes would be as unrealistically high as Monopoly money; and his losses, in the improbable event that he suffered any, would be graciously absorbed by his hostess, while his winnings would be strictly between him and Internal Revenue. Not that winning would necessarily be easy. The rich, he knew, were often surprisingly adept at the game, some of them possessing an almost uncanny sense of values, while others exhibited a well-calculated dash and flair. None of them, with only a paltry few thousand at stake, was ever intimidated from backing his judgment. And he would be playing with the nobility, no less. But this time it had to be different.

He had known it the moment he had answered the phone in his Hollywood apartment that morning and heard Edna’s voice. “Wink, I know it’s unpardonably short notice, but could you possibly catch a plane...this morning...yes, for the weekend...you see, my sister, Jeanne, is here...and a Prince Polensky...and Fred is away...Argentina, I think...I can’t promise you anything exciting...but...I’d appreciate your coming, Wink...”

He had shrugged. What do you say to a woman whom you once called at three o’clock in the morning—a black and desperate morning—and asked for a million dollars—pledging what ever was left of a shopworn soul as security—and what if that woman had calmly said, “Of course, Wink...cash, I suppose...oh, dear, would eight o’clock be soon enough?” The fact that Edna Mallory was the world’s ninth richest woman—or was it eighth?—was really beside the point. It was also beside the point that, as it turned out, he hadn’t needed the million after all.

In the limousine from O’Hare, Edna had been her usual bland and unruffled self. Her foster sister, Jeanne, had arrived from Paris for an indefinite visit two weeks before. Instead of being pale and depressed as an aftermath of her divorce from the Count, however, she had appeared little short of radiant. True, the Count had kept her money and left her virtually penniless, but then he really needed it more because, after all, he was keeping three separate ménages in different parts of Spain. And there hadn’t been any children, at least not Jeanne’s.

Jeanne’s radiance, it seemed, stemmed from not merely one new interest, but two. One was bridge.

Jake listened resignedly. “And the other was the Prince, whom she lost little time in importing.”

Edna’s tone and expression remained unchanged. “Exactly. He has an even more impressive title than the Count, of course, but I think the real attraction comes from his being, of all things, a bridge expert. Jeanne asked if she might invite him, and of course I agreed.

“Oh, dear,” Edna said. “Did I give a wrong impression? Forgive me. He is personable, extremely attentive, and a very fine bridge player indeed. Of course, Fred...”

When Fred Mallory, third, the utilities baron, had taken Edna Mayberry’s hand—and her distillery millions—it had been more like a merger than a marriage. Jake wondered whether they’d had to get approval from the Justice Department.

“Spare me,” he said. “I can read Fred’s meter without a flashlight. But what’s this about Jeanne being broke? If she’s your sister, she must have got a vat full of dough—more than one lousy Count could siphon off.”

“Oh, my. I do make things so difficult, don’t I? You see, Jeanne was the daughter of my father’s second wife. He provided quite generously for her—a million, I think—but the bulk of the estate came to me.”

They were entering the hallowed confines of the world’s richest community, stately trees framing an array of impressive estates. Even the air, Jake fancied, smelled different—like freshly minted money. “So she’s holding her silver spoon under the spigot for another droplet or two?”

“In a way, I suppose.” Edna wafted her handkerchief. She always gave the impression of being overly warm, but Jake had yet to see her really sweat. “You see, after the divorce, Fred helped me set up a trust fund for her with an ample income, but we didn’t feel—Fred didn’t feel…”

“Like kicking in with the candle-power to light up three more ménages in Spain?” He paused. “Edna, did Fred ask you to call me in—like the adjustment department—to win back the money he blew playing against Jeanne and the Prince, and before he throws the master switch?”

“Of course not, Wink. It’s true, we did lose a little—about thirty-five thousand, I think. But then, Fred and I always play wretchedly together. Besides, I take care of all expenses connected with bridge.”

They had turned through an imposing gateway and were cruising along a curving driveway through what appeared to be a public park—minus the public. “I gather that Jeanne and the Prince like to play set. Who made up the fourth after Fred pulled the pin?”

“Our neighbor, Randy Maxwell. You know Randy. We played the last four nights. We lost—altogether, I think—about twenty five thousand. Not over thirty.”

Randy Maxwell was an electronics engineer who had snowballed a few patents and a gift for finance into a mountain of gold. A widower in his early fifties, Randy now piddled around the house in a three-million-dollar workshop and read books on philosophy. But Jake knew him for a keen and competent bridge player.

Fred Mallory was something else; a strict hatchet man at the bridge table, but the hatchet only worked one way—North and South. Yet each, playing with Edna, had lost about the same amount. The Prince, he decided, must be a hell of a bridge player.

He put a firm but tender hand on Edna’s arm as the car drew up to the front door. “Edna, did you call me from California just to check on whether your game was slipping?” He did not mention that he had canceled a lecture and run out on two new clients in order to come.

She was looking straight ahead. “I realize it was selfish of me, Wink. I—just wanted to make sure. You’re the only one…”

He looked at her, this middle-aged, bovine-faced woman with her potato-sack shape, and wondered whether any passion could transcend the fondness and admiration he felt toward her. She could have bought and refurbished a destroyer for a private yacht and filled it with the sycophants of her choice, people who would toady and grovel twenty-four hours a day to assure her that she was both beautiful and brilliant, or even—God forbid—sexy. Instead she chose to spend a fortune traveling month after month to major bridge tournaments, subjecting herself to the rigors of the pasteboard jungle and the grueling discipline of crossing swords with the sharpest wits in the kingdom of competitive sports. She paid the price in blood and guts and paid it like a lady because, deep down, it was more important to her to be a “do-er” than a mere “be-er.”

With the footman holding the door and staring stonily, he leaned over and kissed her...

At dinner, the Prince orchestrated the table talk like a maestro, remarking on how he had followed Winkman’s exploits for years, both at and away from the bridge table, and scattering the names of European bridge luminaries like a flower girl as he tripped from chalet to chateau with a sprinkling of discreetly spiced anecdotes.

Clearly outgunned, Jake took a leaf from Edna’s book and went along quietly. The famous Winkman wit, he knew, was chiefly notable for its backfires, and he sensed an undercurrent that was already combustible enough. He patted Edna’s plump knee under the table to express solidarity among the minority, and they repaired to the card room for liqueurs.

After two hours, Jake was convinced that Edna was not fighting a slump, and the idea that her game might have slipped he had considered ridiculous from the first, She had been his client for more than a dozen years—second oldest to Doc McCreedy—and her game was still growing, maturing, becoming stronger both technically and tactically. But had she thought so? With Edna you could never tell. They had won two small rubbers and lost a larger, slowly played one, and her errors, judged analytically, were minimal. She went down on a small slam that could have been made, but Jake, following the fall of the cards, endorsed her misguess.

“Oh, dear,” Edna said. “I was afraid I should have taken a different view. I just can’t seem to bring home the close ones.”

“Pretty hard,” Jake shrugged. “So far the defense around here has operated like its legs were crossed and wired.”

It was true. From the moment the cards were dealt, the Prince had put away his cultured pearls of patter and begun to play with an almost mechanized concentration. Moreover, his game was strictly engineered for high-stake rubber bridge, a style often difficult for the matchpoint tournament-oriented player to adjust to. His bidding was both daring and disruptive, pushing distributional hands unconscionably; while on defense he keyed solely upon defeating the contract. In high-class tournament competition his style would have earned a reputation for unreliable and erratic bidding, imprecise defense, and fetched him below average results. But he had coached the Countess well, and they made a formidable combination where the payoff was in big swings. Nevertheless, when the session ended, Jake and Edna had a small but tidy plus.

“Oh, dear,” Edna said, meticulously dating the score sheet and passing it to the Prince and Jeanne for their initials. “It was such a pleasant session, wasn’t it? I’m sure we all thoroughly enjoyed it.”

The Countess, relieved of her quiet intentness, yawned prettily and stretched. The moment was perilous, but her bodice held together. There was a faintly calculating glint in her eye as she stood up and tucked her arm under Jake’s.

“I’m only sorry,” she said, “I didn’t take Edna up on those lessons from you long ago.” She squeezed his arm and emphasized it with a little pressure from her thigh as they moved toward the stairs. Her manner was obvious enough even to put a crack in the Prince’s faultless façade, particularly when she stood aside and insisted that the Prince and Edna precede them up the stairs.

Jake, whose reputation with the fair sex was considered by many to exceed even his prowess at the bridge table, recognized that he was being operated upon, but was unclear as to just how extensive a program the Countess might have in mind. He returned the pressure to let her know the game was on, and prepared to await developments, the Prince’s darkly clouded face notwithstanding. He didn’t think he’d overdone it, but the Countess lost her balance slightly, causing him to glance down. Stepping from tread to tread revealed her slippers beneath her floor-length gown. To his surprise, they were neither needle-heeled nor next-to-nothing sandals, but quite substantial affairs with sensible Cuban heels.

She covered the moment with a gay little laugh. “I’m afraid my balance is a trifle off, Jake. Fallen arches. My doctor in Paris has me taking special exercises and even insists on my wearing clumsy shoes. Swimming tomorrow? Elevenish?”

“That should do it,” Jake said, eyes narrowed thoughtfully. “I ought to be braced for you in a bikini by then.”

The next day, however, brought one of those quick changes in weather for which the Windy City and its suburbs are noted. Thunderstorms and a stiff breeze and angry white-capped rollers invaded the beach, and Winkman passed the morning losing a few dollars to Polensky at billiards.

Jeanne appeared for lunch wearing an avocado sweater, cerise stretch pants, and dark green boots, while Edna wore a hand-crafted holomu that looked like a hand-me-down from the washer-woman. Jake could feel the impact like a thud in the brisket, but Edna seemed unaware of the beating she was taking on the fashion front. Luncheon over, they turned as one to the card room.

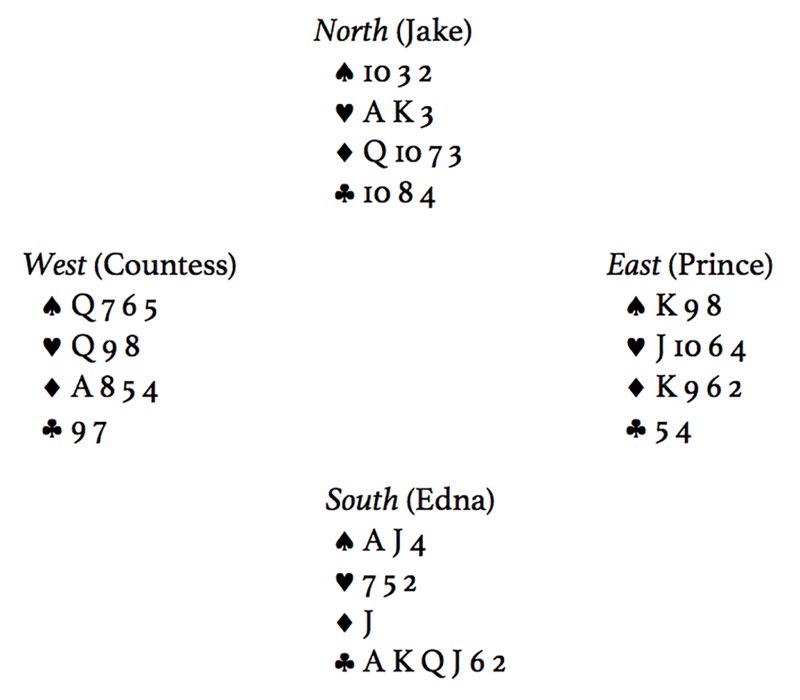

During the first rubber, while Jake was continuing his appraisal of the Prince’s game, Edna pulled to a five club contract—when three no trump was cold.

Jeanne led the spade five, with Edna capturing the king with the ace to lead the ace and a small club to dummy’s ten. She then made the only play which would give her a chance for the contract—a small diamond—and one that would have prevailed far more often than not. The Prince took his time and then produced the killing play—up with the king. When Edna later tried a ruffing finesse with the diamond queen to dispose of her losing heart, Jeanne produced the diamond ace for a one trick set.

“I’m terribly sorry, Wink. I shouldn’t have pulled.”

He shrugged. “Polensky just pulled another devastator on you. We still get the hundred honors.”

The Prince’s eyes flashed. “Thank you, but it was elementary. If Mrs. Mallory had the ace of diamonds, the hand was cold. I had nothing to lose.”

Jake let it pass. The world was full of bad analyses, including, sadly, many of his own. But switch the singleton jack of diamonds for the singleton ace, and give Jeanne the spade jack for the seven, and the Prince’s play would have looked pretty silly.

But there was no denying the effectiveness of his dashing style. He and Jeanne hit a small slam that was cold but hard to reach, and followed it up with a grand slam that was tighter than an actor’s girdle. But it wiped out Winkman’s winnings and put the icing on the session. They abandoned the table for cocktails, and then went upstairs to change for dinner.

The evening session got underway with Jeanne, ravishing in another floor-length creation, producing an unexpected defense.

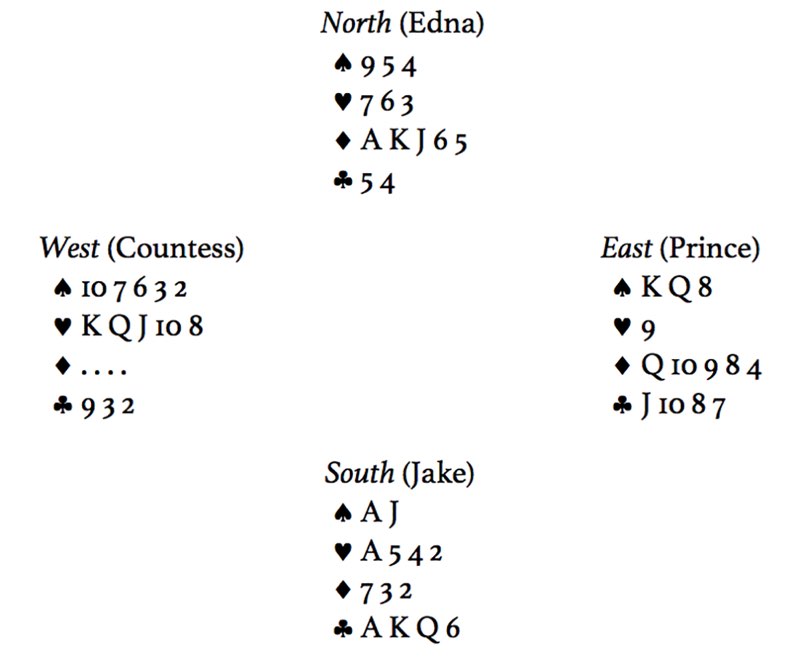

Jake opened with a club, over which Jeanne bid a Michaels two clubs, showing a weakish hand length in the majors. Edna called two diamonds, and Jake reached for three no trump, promptly doubled by the Prince.

Jeanne led the heart king, which held, and continued with the queen, taken by Jake, the Prince discarding the diamond four. This play virtually marked Polensky with five diamonds, and Jake’s lead to the diamond king confirmed the situation when Jeanne showed out. Jake then cashed three rounds of clubs, and when Jeanne followed to all of them, be had a pretty solid inferential count on both defenders’ hands—West 5-5-0-3, East 3-1-5-4. He judged further that the Prince might well have a spade trick, as well as minor suit stoppers, for his double. If so, the forceps were in position for a suicide squeeze, and he threw Jeanne in with a heart. She promptly cashed another heart, the Prince discarding first the spade eight and then the diamond nine, to bring about this position:

If Jeanne now cashed her last heart—as Jake confidently expected—the Prince would be ground in the teeth of a progressive squeeze. But after looking long and wistfully at her good heart, the Countess reluctantly led a spade, and there was no way to keep Polensky from taking two tricks.

The Prince dabbed a handkerchief to his forehead. “Pretty play, petite.”

“I’ve had it done to me before,” Jake sighed. “By someone like Sheinwold and Kaplan. But one of you is better looking, and the other makes it literally royal.”

Jeanne laughed gaily, but as one close contract after an other fell to a withering defense, and as she and the Prince piled up the score, she finally turned to Edna. “I’m really sorry, dear sister. I know how you must feel—when you take your game so seriously.”

“On the contrary,” Edna responded easily. “I can’t remember when I’ve enjoyed myself so much. Wink has proved a marvelous catalyst. Your and the Prince’s game has grown so much stronger since he came. It’s become almost exquisitely relentless.” She sighed and waved her handkerchief. “I do hope I’m learning something.”

The Prince was nimble. “Mrs. Mallory is too modest much. Your game superb is. We have been very lucky. It is of a certainty that about our cards complain we cannot.”

Jake bit down on his tongue. This savored of the patronizing pap used to console pigeons in a high-stake game where they did not belong. He had spotted far too many flaws in the Prince’s game to warrant any such condescension toward Edna. “Is it possible but,” he asked dryly, “to deal while one the manure spreads? I have the feeling that our luck about may later turn.”

And turn it did, but only for the worse. It seemed as if the Prince, resenting Jake’s drollery, had determined to turn it on in earnest. The cards cooperated, and Jake and Edna took a merciless flogging. But Jake, as with almost everything else, had a technique for dealing with such situations. Having ruthlessly exorcised all superstition, he knew that judgment could be a chemical fugitive, and that once depression replaces perception at the bridge table, the victim will be contributing far more to his beating than the opponents. His answer was to forget the score, wipe out all previous hands, and to concentrate on each new hand as a fresh and isolated problem. And shuffle the hell out of the cards. He did not say it was easy, and he was grateful that Edna had learned the lesson well.

Her stability in the face of repeated debacles allowed him to keep his analytical searchlight cool and probing.

Against Jeanne’s three no trump, Edna opened the heart trey. Jake was up with the ace and switched to the diamond jack, with Jeanne making a well-guessed duck. He continued the diamond nine, Edna taking her ace and exiting with the heart deuce. This was technically correct but strategically dubious, since it gave declarer too good a count on the hand. For Edna was now marked with five hearts and two diamonds. Her black cards, as well as her partner’s, would almost surely break 4-2 or 3-3. If the latter, declarer had the rest; if the former, and Edna held four spades, the contract was a latch.

Jeanne won in her hand and rapidly played the spade king, followed by the ace and king of clubs, playing dummy’s seven and nine. Eyes bland, Jake now inwardly relaxed. The hand could still be made, of course, by cashing dummy’s top spades, and leading a fourth spade to squeeze Winkman on Edna’s forced heart return. But a player who would fail to unblock the club ten-nine for a simple proved finesse was not about to find the more intricate and unnecessary play. She didn’t, and struggled to a one-trick set. Cashing dummy’s top spades would have ruled out Edna’s holding a third club.

The Prince was gentle. “So fast, cherie, you play. Two different ways but you could have made the hand. Unblock the clubs, or save the heart entry your hand to.”

Jake said nothing, but he noted the Prince underbid the next hand the Countess played, settling for a comfortable four hearts when six was there for the price of a little skillful manipulation. But the Prince, too, was having his problems.

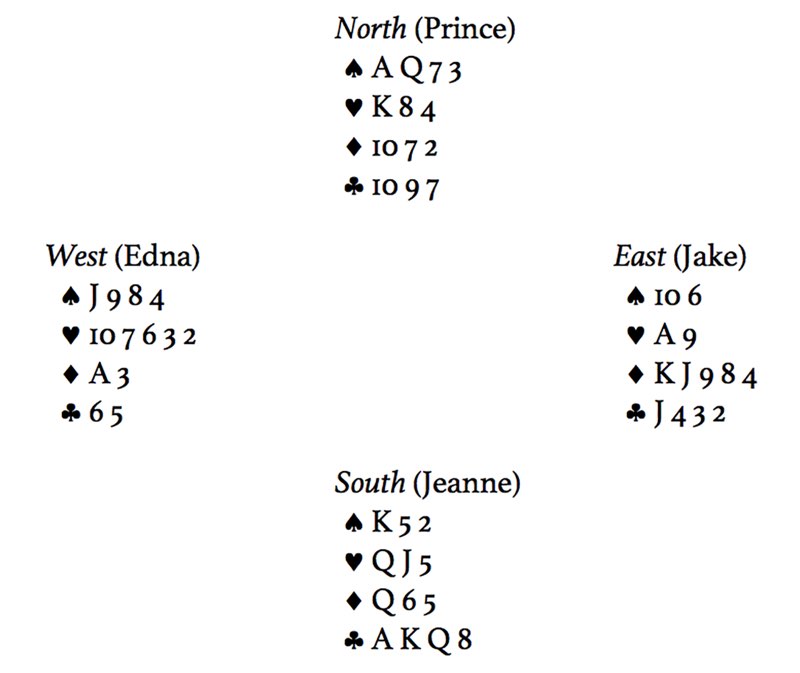

Against four hearts, Jake led the spade queen, ducked in dummy by the Prince, Edna following with the nine. Since this marked declarer with the spade ten, Jake switched to the jack of clubs. Polensky won and immediately shot a low heart toward the board, Jake calmly playing the seven. When Edna showed out, the jig was up and another ice-cold contract went down the drain. Even one of Jake’s beginner clients would have been sitting on toothmarks for a month, had he made such an error.

“Tough luck, partner,” Jeanne consoled, thus marking herself as either a diplomat or a dolt. “All four trumps in one hand…”

But the Prince, enjoying belated hindsight, knew better. Had all four trumps been in the East hand, nothing could prevent the loss of two trump tricks. Therefore, it could cost nothing to insure against their all being in the West hand by simply leading the jack.

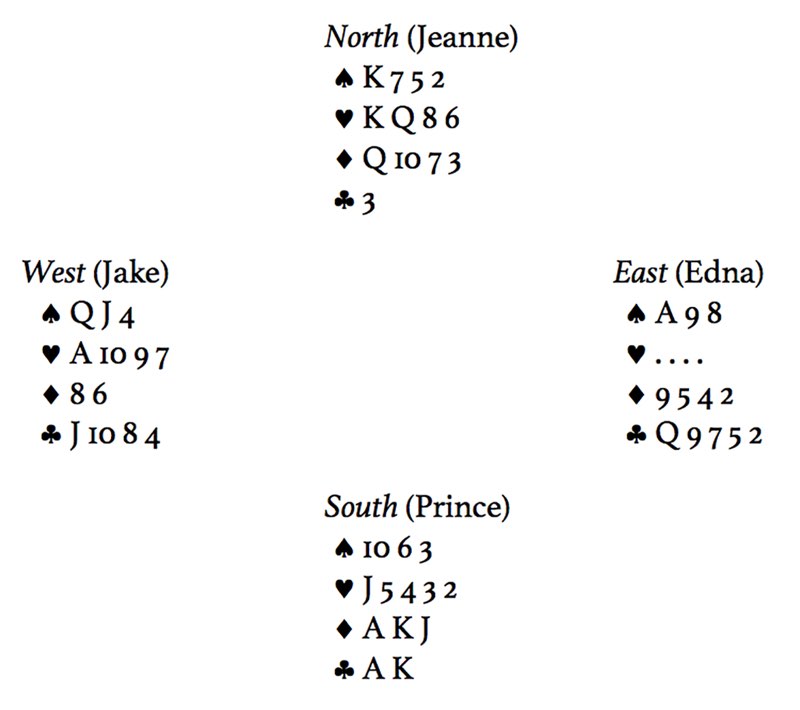

It was food for thought. Were the opponents exhausted from wielding the lash, or grown careless with a surfeit of loot? Winkman did not think so. Rather it seemed that the Prince was smoldering over Jeanne’ s continued rapid but ragged dummy play. If so, it must really have been bugging him, because on the last deal he gave an almost shocking exhibition of ineptness.

Against four spades, Jake led the heart king, Edna playing the eight. He continued with the ace, Polensky trumping. The Prince now carefully laid down the spade king and then entered dummy with a diamond to take a spade finesse on the way back. This sequence was like something from the fortieth of a cent game in the back room at the Y.W. Jake accepted the trick and played a third heart to Edna’s queen. The Prince, down to two trumps, was now in trouble. He frowned and discarded a club, but this feeble maneuver was much too little and too late. Edna stoically produced a fourth heart and another cast-iron contract bit the dust.

As the cards lay, almost any line of play would have worked—except the one chosen by the Prince. Many rubber bridge players would simply cash the ace-king of spades, abandoning trumps if the queen failed to appear, and run the diamonds, conceding two trump tricks but bringing the hand home on the club finesse. Others might have tested the club finesse first, and then “adjusted” their view of how to play the trumps, according to whether the club play won or lost. A slightly more elegant line would be to enter dummy at trick three for an immediate trump finesse—a line that could prevail with the trump queen four deep in the East and the club king off-side—and would leave the spade eight to cover the fourth heart if it lost, and again reduce the hand to the club finesse. It was all very perplexing.

Nevertheless, the session broke up with Jake and Edna minus $38,000, give or take a few hundred.

Jake slept late. The sun was high when, clad in swim trunks and white terrycloth robe, he descended to the terrace, where a sumptuous buffet brunch awaited him.

The Countess was breath-catching in a turquoise bikini with a transparent cover-up that achieved the near-ultimate in futility. The Prince was sartorially resplendent in a tailored robe of bronze and purple with a coat of arms over the left breast. As be turned to accompany Jeanne down to the sand, Jake half-expected to see POLENSKY stenciled across the back. He even sported custom-built beach sandals.

When they were out of earshot, Edna turned to Jake. “Oh, dear,” she said. “I know my game is plodding and uninspired, Wink. But I feel so outclassed. And Jeanne is little more than a beginner. Perhaps I should start all over. What do you think?”

He dispatched the last of his eggs Benedict and poured himself another cup of coffee. He was deft enough at tampering with the truth, but, with Edna, there was hardly ever any need. Inside her doughy exterior, she had a lovely core of toughness that he had seen often bent, but never broken. But he could sense that she was uniquely vulnerable now, and that the breaking point was perilously close. Was that why, without quite knowing it herself, she had sent for him? He mentally riffled through his file of clichés, but after a dozen years of coaching her under the stress of tournament pressure, there was very little he had left to say.

He put down his coffee cup. “Your game is not the greatest, Edna. Maybe someday it will be. But it has integrity, and it’s always around the target.” He paused, groping. “Bridge and golf are very similar disciplines.” Edna in her culottes would never make the cover of Vogue, but she was a steady and competent performer on the links. “Horton Smith was a great golfer in the Hagen era, and, like most pros, a deadly putter. The press, always seeking the sensational, gave rise to the belief that Smith won tournaments because he knocked the ball in the cup from anywhere on the green. Once asked the secret of great putting, he gave a simple, unsensational answer. ‘The guy who sinks the most putts,’ he said, ‘is the guy who’s closest to the pin.’ Remember that, Edna.”

Jake strolled down to the beach and caught the Prince emerging from the surf. Polensky made a business of arranging his beach towel, but there was a moment when he stood barefoot, erect, and quite close. Jake slid his eyes to the horizon and back to make sure. The Prince’s eyes were a good two inches below his own.

“Where’s the beautiful Countess?” he asked.

“Along the bitch she swims, and then back walks to exercise her feet,” the Prince volunteered, quickly dropping onto his towel.

Jeanne appeared around an abutment that shielded the private beach and walked toward them along the hard-surfaced shore just above the wave-line. “Hi, champ!” she called to Winkman, accentuating the sway of her hips a trifle. “Say,” she added, coming closer, “you look like an Olympics champion instead of a bridge expert.’’

“But which Olympics?” Jake sighed. “Anyway, it’s an illusion. We have so many in our culture, don’t we?”

She laughed. “Is this a new game? Find the hidden stiletto in that remark?”

He shrugged. “My stilettos are never too hard to find, Countess. Just check the nearest bull’s-eye.”

He left her biting a pensive lip and walked out into the surf. As a Midwestern boy, he knew the coldness of the water in the Great Lakes, but years of sheltered living around tepid pools had softened him unmercifully. He had to clench his teeth to keep going, and total immersion rivaled the ecstasy of crawling into a casket of ice. But after a dozen strokes or so, he began actually to enjoy it. It was so brutally elemental, it gave one a sense of conquest to survive. He turned and began to sidestroke his way along parallel to the beach. It was in such repetitive and mechanical activities that be often did his best thinking.

Cheating, of course, was always a thing to be considered. But to attempt to cheat against him would have required a rather massive ego. In his time he bad been retained by trans Atlantic cruise ships, various old line clubs, private blue book clients, and even by operators of back room cigar store games. Regardless of the site, the means were always limited, and be could almost check them off in his sleep. The adept dealer, the marked cards, the cold deck, the sloppy shuffler, the one-at-a time-card-picker-upper. Then there were the tired old mechanical props that every bridge pro knows by heart. The tinted glasses, the hearing aid, contact lenses, the motorized wheelchair, the electronic cane, the peephole, the colleague with the binoculars, the hole in the ceiling, the taps from the floor below. Moreover, he was certain that Edna, in her bland and simplistic way, bad managed to inform her guests of Winkman’s familiarity with this sordid side of card life. It all made for a nice problem. Keeping the solution equally genteel might not be so easy. But he thought again of that sweat-racked night, when, with no other place to turn and with a man’s life in the balance, he had turned to Edna...

He was becoming numb. He had heard that people had frozen to death that way, in a sort of tranquil euphoria, and switched to a vigorous overhand stroke, heading directly for the beach. He came ashore at a private beach two estates to the north of the Mallorys’. It was deserted and be was plodding along, heading back, when a cheery voice called to him.

Jake recognized it at once as coming from Randy Maxwell. He turned to see the financier beckoning to him. Maxwell was attired in disreputable shorts and a stained T-shirt, and was standing at the entrance to what appeared to be a well-tended jungle. Jake joined him and saw that the trees concealed a squat functional building of concrete and hollow tile.

“My hobby shop,” Randy explained. “Since the word ‘work’ is vulgarly de trop around here, I had to draw it up as a ‘summer house’ to get a building permit—and then hide it.”

Inside, even Jake’s unsophisticated eye could detect a few hundred thousand dollars’ worth of electronic toys. “What do you do in here?” he asked. “Besides compute relative strength indices on the Dow Jones averages.”

Randy laughed. “Believe it or not, I’ve got a computer that does just that. Mainly, I piddle. What I’m really trying to do, I suppose, is recapture what I had in my garage down on South Sangamon Street twenty-five years ago. I used to piddle with impractical, noncommercial things, and one year I made twelve million. Now, of course, such things are done in what is called a laboratory, and it’s considered unseemly for me to be caught in one. I pay young squirts fabulous salaries to do what I’d cheerfully do for nothing.” He pointed to the array of equipment. “But it isn’t the same. I just don’t get the ideas any more.”

“Even the Greeks didn’t have a word for it,” Jake said. “Slip me another Polaroid, and I’ll sit down and weep with you, Alexander.”

Maxwell shook his head. “It would spoil you, Jake. I wouldn’t want to be a party to that. Integrity is fine, but it’s twice as fine when it costs till it hurts.” He turned cheerful again. “Here.” He handed Jake two plastic boxes about the size of matchboxes. “Let’s try something.”

“Behind you and to your left,” Randy went on, “there’s a cabinet with a shelf full of large capacitors.”

“What’s a capacitor?”

“A radio-electronic device. There are also some small condensers.”

“Same question.”

“Same answer. I am going to tell you how many of each. Listen closely.”

Suddenly Jake became aware of a soundless tingling in his left hand and recognized a series of six impulses. Then came a series of shorter or lighter impulses. “Six capacitors and ten condensers,” he said. “The last time I was in your house you had a bottle of Scotch that talked in a whiskey tenor. I liked that trick better.’’

“Me, too,” Randy said. “But we have to be practical.”

“Indeed. And what will this thing do? Communicate with your refrigerator to give you different colored ice cubes?”

“It is one of the world’s great myths, Jake, that real progress comes from creating to fill a need. Such efforts are always stodgy and pedestrian. Create first; find the need later. Check that cabinet.”

Jake checked and found the six capacitors and ten condensers.

“Now move a number of condensers down to the next shelf and tell me how many by pressing down with your right thumb.”

Jake moved three, and pressed down on the black box in his right hand three times.

“Three,” Randy said. “Isn’t that nice? No wires, no sound.” A phone rang. “Damn,” he said, putting it down. “Another directors’ meeting. Got to run. Stop over for a drink before you leave, Jake.”

Jake resumed his stroll along the beach, coming presently to the abutment where he had first spotted Jeanne. He found himself almost treading on her small but well-formed footprints.

Edna’s beach was deserted, and he gathered up his robe and headed directly for his shower. Coming out, he began carefully to pack. He worked at remaining cool and dispassionate, sipping rye and water because it seemed to him to have a clean taste. Sometimes he even brushed his teeth with it. But the sour nausea was not in his mouth or stomach. He took a deep breath, followed the broad upstairs hall to the south wing, and tapped on Jeanne’s door.

The Countess was reclining on a love seat in canary yellow lounging pajamas and looked almost feverishly fetching. She sat up and gave him a warm smile. “Let me fix you a drink. What a pleasant surprise. But this is hardly the hour for a seduction, is it?”

Jake sat down across from her and accepted the drink. “I wouldn’t know. I haven’t gotten around to punching a time card on it.’’

She laughed. “You’re such a devastating rebuker, Wink. Do you really enjoy cutting people up, or is it just a pose?”

“In this case, neither,” Jake said. “It’s a job. Something like swabbing down the head—somebody has to do it. It’ll help if we omit the headshrinker jargon about sibling hostilities. You and Edna were raised as sisters, but you have everything, and she’s a dowdy frump. You glitter and sparkle and have royal consorts, and all she can do is blink her bovine eyes. Of course, it’s unbelievably cruel that she should have the money instead of you. But I don’t think money is the whole story, Jeanne. You could marry a bundle. It’s got to be something else. Edna’s got something that infuriates you. It completely distorts your perspective. You’ve spent years pirouetting around her, mercilessly tossing your darts, artfully searching out her most vulnerable parts. You do it with your clothes, your style, your men—you’d even toss in an affair with me, once you sensed it would wound her. But Edna won’t show hurt. That’s an aristocracy that you just can’t comprehend. Over the years, you’ve hit her with every thing in your sick arsenal. But she won’t show hurt. She just chews her cud and endures it. But suppose you could humiliate her at bridge? She couldn’t pretend to ignore that, could she? And with me as her partner? The skin should really be thin and tender there, shouldn’t it? But your vaulting fury overreached itself.”

The Countess’s face was a white mask. “Indeed? In what way?”

“You got carried away by the caprice of a few cards. You wanted the ecstasy of plunging the knife yourself. You played the dummy too fast for little Sergie to clue you. Not that he’s the greatest…”

Her face was suddenly mottled with rage. “Why, you—you point-count gigolo. You cheap pasteboard mercenary. Don’t you dare speak to me that way. Don’t tell me you’re really fond of the old sow! How much is she paying you? Tell me that!” She was standing over him, her bodice heaving.

Jake sipped his drink. “Edna would never pay me for a favor, Jeanne. Besides, anything I could do for her was paid for long, long ago—and not with money.” He looked out the window. “I’m a creampuff as well as a dreamer, Jeanne. I can’t protect Edna from all the hurts in the world, much as I might like to, but I can protect her from a pair of filthy frauds—and will.”

She turned suddenly calculating. “Oh, come now. Let’s not make wildly slanderous statements. Besides, Sergio—”

Jake sighed. “Sergio said we can always buy him. But you see, Countess, Sergie is sadly two inches shorter on the beach than in the drawing room.”

Her eyes narrowed. “So he wears elevator shoes. What has a little male vanity got to do with anything?”

“About the same amount,” Jake said, “as phony fallen arches. Half-firm sand takes a fairly revealing footprint. You may be fallen, Countess, but the problem is not in your arches.”

“Just what are you getting at?”

“Many things. None of them pretty. I suspect that against Fred and Randy all you really needed was the receiver, which you could hide in your hair, and, consequently, there was no mention of your bad arches and clumsy shoes. But when I came into the act, you had to go on two-way communication. That’s why you wanted me beside you and Edna ahead of you when you went up the stairs. Is that enough? I’ll deal with Sergie later.”

She gave him a venomous glare. “That does it! The only thing you’ll deal with later is my attorney.” She grasped the top of her pajamas, ready to rip. “If you’re not out of here in five seconds with your lips sealed, I’m going to scream rape!”

But Jake wasn’t there to protest. “Excuse me for being rude to the crude,” he said, from the region of her closet. “A topless bridge player should make a peek worth even more than two finesses. But I’m after even bigger skin game.”

He returned with an armload of her shoes. Whether it was this or his remark that inhibited her, she did not scream. Several of them, he noted, were made by a custom cobbler in Florence, and had one feature in common—a nice substantial heel. A little toying revealed the clever way in which they could be detached, and the equally deft manner in which they bad been hollowed. Quite enough to conceal a little black box—one in each heel.

He sighed. The rich often spoke in parables. Randy Maxwell would never dream of accusing one of Edna’s guests of rooking him out of thirty grand. But he’d spend a week figuring out how it was done, drop suave and subtle suggestions to Edna about importing Jake Winkman, and then contrive to get Jake to do the dirty work. But the really important task remained.

The Countess, watching him, had difficulty lighting a cigarette. She blew out a cloud of smoke. “Okay. Now what?”

“I go through the rest of your shoes and search the room until I find the transmitter and receiver—or you hand them to me.”

She dug them out from behind the cushions of the love seat and handed them to him, a look of actual triumph suddenly lighting her eyes, “There. Now call Edna and explain to her how her little sister and ward abused her hospitality and cheated her. Go on. Maybe she’ll prefer charges, and we can make an international thing out of it.”

He smiled ruefully. “No wonder you’re such a lousy bridge player. Listen to me, Jeanne. I don’t think you’re all that bad, or all that stupid. Besides, I need your help. Edna wouldn’t prefer charges. She’d probably apologize for inspiring your perfidy. But she’d be hurt, and we don’t really want that, do we?”

She gawked. “Are you kidding? I should cooperate with you to spare that cretin’s feelings! Just how will you manage that?”

“By cutting out your heart, if I have to,” Jake said. “We’re going downstairs in a few minutes for a session of bridge—and just in case there’s more of these around—you’ll be wearing bedroom slippers.”

She sat forward in rigid disbelief. “So you can cut Serg and me to pieces just to plaster up Edna’s ego? And take back our hard-earned money? Do you realize how much time and effort we— Try to make me!”

“If you insist.” He moved to the door. “I’ll let pride put a pitchfork to your derrière. You see, Jeanne, Sergie is not a bridge expert.”

“Not a bridge expert!” She actually goggled. “What do you mean? Why everyone—even Edna—has complimented him on his game. At Nice and Cannes he was always a big winner.”

Jake shook his head. “He played too well,” he said, “on defense. When he was practically looking at all four hands. Bridge doesn’t work that way. There are a hundred fine dummy players for every topflight defensive player, He is a middling fair casino-style player—what we call a palooka-killer. Since you asked for it, brace yourself: Sergie is a con man. He promoted you for the sole purpose of getting into this house and out again—with a bundle. By involving you, he provided himself with complete immunity even if he was caught. If I know the type—and believe me I do—I’ll bet he brought his mistress along when he followed you over here. He’s got her stashed at some downtown hotel. Hasn’t he made a quick trip or two to see his ‘consulate’?”

A flash of terror mixed with betrayal lit up her eyes. “That’s a lie! Serge is madly in love with me. We’re going to be married. It was only because of his love for me that we needed—”

“Another fifty thousand shares of RCA. Face it, Jeanne. After our afternoon session, Serge will check with you during the dinner break. Don’t tell him I’ve drawn his fangs. Simply say that you consider yourself a better bridge player than Edna and that, since his is better than mine, why not enjoy the added sport of beating us fair and square? If you really have a sophisticated sense of humor, you’ll enjoy the look that comes into his eye. But within an hour after the evening session starts, little Sergie is going to get an urgent call. His Upper Slobovian uncle, the grand duke, is dying in Zurich. Surely he’s told you about the grand duke…”

Her mouth was like a thin fresh scar. “You are the most despicable, cynical, skeptical rat-fink I’ve encountered. Get out!”

The afternoon session was a subdued affair, with both the Countess and the Prince playing with a withdrawn, almost desperate intentness. Edna, appearing not to notice, was nonetheless impelled to flow copious coats of lacquer to preserve a patina of social grace. The cards ran flat and indecisive, but Jake drove them, scoring game after game with the aid of a little inept defense. Three times he pushed to the five level in quest of dubious slams, but each time, failing to hold the critical controls, Edna correctly signed him off. He was almost equally relentless in presenting Edna with tough, brutally stretched contracts, but she bagged far more than her share with beautifully judged dummy play.

“Oh, dear,” she observed, as the session broke up. “I seem to be so lucky today.” Her eyes met Jake’s blandly. “You played magnificently, Wink. It’s such a pleasure, isn’t it? Thank you. Shall we resume about eight? I must tell Hanson.”

She presented the score to Jeanne and the Prince. They were down $27,000.

Edna’s performance at dinner, Jake decided, deserved at the very least an Academy Award. She was serenely solicitous, fumbled the table talk into channels that were as bland as an ulcer diet, and avoided any word or mannerism that might hint at a feeling of triumph. How much did she know? Or suspect? He’d be damned if he could tell. He thought of Kipling and of treating those two imposters—“triumph and disaster”—just the same.

He was seated at her right—and that was another thing. For there were two other guests tonight—Randy Maxwell and a dowager by the name of Mrs. Adrian Phelps. Like a litany, it kept bugging him. How much did Edna know? He put down his coffee cup, picked up her chubby hand and kissed it... No one seemed to take the slightest notice, least of all Edna.

The evening session was scarcely under way before Jake and Edna smoothly assumed a comfortable margin. Maxwell and Mrs. Phelps were playing a quiet game of Persian rummy at a nearby table. The Prince made one of his dashing bids, ran into a rock-crusher in Jake’s hand, and got pulverized. Randy and Mrs. Phelps came over to observe the carnage. It was almost a relief when Hanson appeared to inform the Prince of an urgent phone call. He excused himself to take it in the library. When he returned, his face was clouded.

“I am prostrated,” he announced. “An unpardonable turn of events. I must at once leave. It concerns a matter about which I cannot speak.” He bowed deeply and headed rapidly for the stairs. The Countess looked as if she had been drugged, but Jake noted a tiny ember smoldering in her eye.

The whole tempo went into a new gear. Many things happened fast, but there was an almost stage-like coordination about them, so that they seemed to take place with slow-motion definition. Edna withdrew to a nearby escritoire and carefully wrote a check. The Prince’s bag appeared almost as if by magic in the front hall, followed by the Prince himself. He accepted Edna’s check, clicked his heels, and was gone, a waiting cab whisking him away. Mrs. Phelps was in his seat at the bridge table, calmly shuffling the cards.

Randy Maxwell lit a cigar and nudged Jake toward the library. “The call came from the Uppingham Hotel on East Delaware, but it was a little cryptic.” He blew out a puff of smoke. “You did want me to tap the phone, didn’t you?”

Jake shrugged. “What else, Steinmetz? It was probably better than bribing Hanson to listen in.”

“Oh, much better,” Randy agreed. “Some people are so devious.” He took a small radio from his pocket. “I just happen to have this tuned to the cab company’s frequency.”

There was a squawk...“thirty-seven to dispatch...pickup at Mallory...destination Pierpont Plaza...ten-four.”

Maxwell pocketed the radio and turned to Jake. “You see? Perhaps we can have that drink next time.”

Jake’s bags had replaced the Prince’s in the hall, and a Mercedes was idling under the porte-cochère.

“Mrs. Mallory ordered it brought round when she saw your bags,” Hanson said, “I daresay you’ll leave it at the airport, sir?”

Jake nodded. ’Td rather not disturb Mrs. Mallory just now. Say goodbye for me when she’s free. In fact, give her a kiss for me, Hanson.”

“Only you could do that, sir. You’re the only one I’ve ever seen—I think I may have said too much, sir.”

Jeanne was in the front seat. He whipped the car out through the long curving driveway. “You’re about to get your ego shattered, Countess. Are you sure you can take it?’’

“Drop the Countess stuff, Wink. I’m a skurvy, rotten nothing. I need a catharsis.”

“Castor oil is cheap.”

“But it won’t make me into an Edna?”

“Only Edna could make Edna.”

She was silent for several miles. “Wink, what do you honestly think of my bridge game?”

“With or without an electronic mirror? Without, it stinks.”

“I know it stinks. I meant do I have the latent ability?”

“Anyone has the ability; not everyone the guts.”

Nothing more was said until Jake pulled into the parking lot of the Pierpont Plaza on Chicago’s near-North side. She handed him a small camera. “Randy said to give you this. It has a built-in electronic flash that will take pictures in any light.”

“Polensky,” Jake told the desk clerk.”Give me his room number and tell him Jake Winkman’s on his way up.”

The Prince was completely urbane. So was the bleached blonde with the long cigarette holder who lounged on the divan. “It was thoughtful of you to spare Mrs. Mallory the scene,” he said. “But you have had a trip for nothing.” He completely ignored Jeanne. “Mrs. Mallory will not make the charge. Nor Mr. Maxwell. Nor will she stop the check.” He shrugged his shoulders. “So there is to discuss really nothing.”

“True,” Jake admitted. He unstrapped one of the Prince’s bags, sprawling the contents on the floor, and came up with a shoe. He calmly detached a heel, placed shoe and heel on an end table, and proceeded to photograph them.

The Prince suddenly changed to a tiger, showing his fangs in the form of a small automatic. “Give me that camera. I demand also payment for my ruined shoe. Then out get or I will shoot!”

Jake snapped his picture. “Sergie, you are many things, but a gunman isn’t one of them. Besides, Mr. Maxwell doesn’t trust me. I spotted two detectives from the Bronco squad in the lobby.” He snapped a picture of the blonde. “Be a good fellow and give me the check.”

The tiger turned to a fawning jackal. “But that I cannot. I have the expenses.” His eyes slithered to the blonde. “Very heavy expenses. And I need money Europe to return.” He spread his arms. “Let us like gentlemen the compromise make.”

The blonde began to pack. It didn’t take her long.

Winkman shook his head. “These pictures and a full report will go to the American Contract Bridge League and the World Bridge Federation. You’ll be blown from Oslo to Oskaloosa, right down to your denture charts. You’ve had it, Sergie. The check.”

The blonde hustled her bags to the door. “Serg, you always were a yellow fink. The man says two words and you curl up like wet spaghetti. He hasn’t a thing on you that would stand up. You could sue and double your money on a settlement. Mrs. Mallory would no more let this come out in court than fly. Her own sister… The least you could do is beat this man up and throw him out. Goodbye!” She slammed the door.

The Prince was nervously lighting a cigarette. He flung it down in a sudden gesture of ultimate frustration and made a desperate lunge at Winkman. At the last second, Jake stepped aside and measured him for a Judo sweep that scythed his legs from under him and dropped him like a bag of wet cement.

He leaned down and retrieved Edna’s check from the Prince’s wallet. Maxwell’s check was missing, but there was $20,000 in large denomination bills with the bank’s paper strap still around them.

He held out his hand to Jeanne. “Give me your lighter.”

White-faced, she handed it to him and he touched the flame to the check.

Three more times on the way to the airport, he asked to borrow her lighter.

“That—that woman,” Jeanne said, as they pulled into O’Hare, “She was right, wasn’t she? You just psyched him.”

He looked at her and sadly shook his head. “Let’s just say I seldom psych.”

She sat up as if suddenly galvanized. “Good heavens! Do you actually believe that Edna might have done it? Reveal herself and the great Fred Mallory as dupes and unwitting shills—and her own sister as a crook! Do you honestly think—”

“I don’t know,” Jake said softly. “Edna’s a quality person. I suspect she’d choose the integrity that cost her the most. I’m glad it won’t be necessary. Lighter, please.”

She was silent as he slid out of the car, gathered his grips, and handed her the envelope with the $20,000 for Randy Maxwell.

“Jake...wait. Why have you kept borrowing my lighter? What happened to that beautiful gold lighter Edna gave you?”

“It’s in Sergie’s pocket with his fingerprints all over it. I put it there when he went to answer the phone. If he’d made a fuss—as his mistress suggested—I’d have nailed him on grand larceny. And don’t kid yourself that I wouldn’t have pressed the charge.”

She sat looking up at him for a long moment. “For a dumpy, frumpy woman like Edna?”

“No,” he said. “Just for Edna.”

In the rotunda, he picked up a public phone, and got Edna. “I think Jeanne is coming home,” he said. He hoped he had got the right inflection on the word “home.” But with Edna you could never tell.

“Thank you, Wink, we’re waiting. It’s been such a pleasant day, hasn’t it?”