Chapter 1

Popular Panoramas

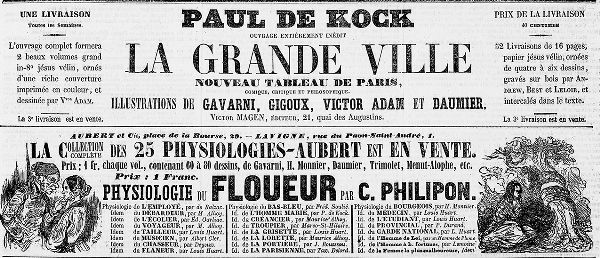

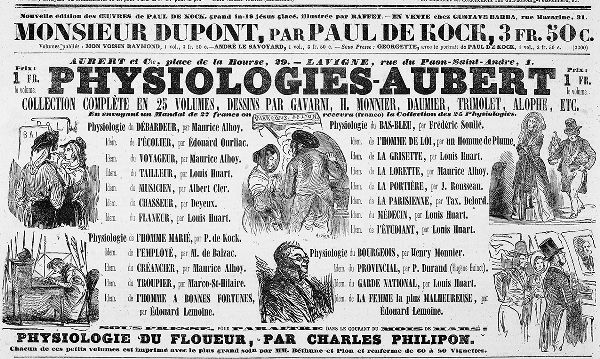

The May 28, 1842, issue of the daily newspaper La Presse contained two ads on its back page, one directly above the other, that publicized the sale of similar yet importantly different works—one a larger volume, the other a smaller and less expensive one (fig. 1). The first advertised La Grande Ville: Nouveau tableau de Paris, a compilation of short chapters depicting diverse urban types and occurrences by one of the period’s best-known writers: Paul de Kock. The name of this exceptionally popular, prolific novelist and playwright, the subject of chapter 4 of this book, was in boldface and centered across the top of the ad, a sure draw for his abundant readers. The names of a number of similarly famous illustrators who contributed to the work were also included: Gavarni and Daumier, to name only two. The advertisement gives little indication of the content of the work; instead it focuses principally on the material features of the different formats in which it will be sold. With one installment for each week of the year, La Grande Ville, the ad explains, could be purchased individually as illustrated installments for the price of 40 centimes apiece (“52 Livraisons de 16 pages, papier jésus vélin, ornées de quatre à six dessins gravés sur bois par Andrew, Best et Leloir, et intercalés dans le texte).”1 Once all the installments had been produced, clients could alternatively buy “2 beaux volumes grand in-80 jésus vélin, ornés d’une riche couverture imprimée en couleur, et dessinée par Victor Adam.”2 This announcement calls attention to the high quality of the large-format paper, cover, and craftsmanship of the product, underscored by the use of the adjectives beaux, grand, and riche as well as the names of known illustrators. Either as a luxury item or a series of installments, the physical qualities of these two versions of La Grande Ville were theoretically different enough that clients could in fact purchase both products. As the promotion for this text makes clear then, La Grande Ville was packaged as a work that was sure to sell and, as such, a profitable gamble for its publishers.

Fig. 1. Ads for Paul de Kock’s La Grande Ville and La Maison Aubert’s Physiologie series. La Presse, May 28, 1842. Bibliothèque Nationale de France.

Directly below the advertisement for La Grande Ville there is one announcing the availability of the complete collection of Physiologie-Aubert, a series of texts sold cheaply at 1 franc per volume, whose twenty-five titles are listed in three columns below. The works include Physiologie de l’employé by Balzac, Physiologie du bourgeois by the caricaturist Henri Monnier, Physiologie du bas-bleu by the popular novelist Frédéric Soulié, and Physiologie de l’homme marié by de Kock, all names either evoked in the previous ad or that would eventually become associated with the second volume of La Grande Ville, published the following year. Each volume in this series, we read, contains sketches by many of the same illustrators as La Grande Ville (Gavarni and Daumier). As if to showcase their talent, the ad boasts two of these illustrations, one a comical rendering of Eve being tempted by a snake with a human head, from the recently issued Physiologie du floueur. As opposed to the publicity for La Grande Ville, this second ad makes no mention of the quality of paper or of the physical properties of the works being promoted. Rather it underscores the inexpensive price of the publications and devotes space to the long lists of titles in the collection, so many that, after the first title in each column, the shorter idem is used in place of Physiologie. Stacked one on top of the other in this issue of La Presse, these two ads publicized works that shared common illustrators, authors, and urban subjects yet were packaged differently, with disparate price points, and seemed to target different audiences. The content, form, and marketing of these related works not only reveal the fluid nature of a particular subgenre but also expose contemporary tensions about literary value and reflect the developments of an increasingly profit-driven marketplace.

La Grande Ville and the Physiologie-Aubert collection are examples of a highly commercialized and self-consciously trendy literary phenomenon that became known in the twentieth century as “panoramic literature,” a concept first evoked by Walter Benjamin. In his essay Charles Baudelaire, a Lyric Poet in the Era of High Capitalism, Benjamin likens these works to the visual spectacle of the painted panoramas—displayed in a rotunda for a complete immersive experience—that were fashionable throughout Europe toward the end of the eighteenth and the beginning of the nineteenth century: “These books consist of individual sketches which, as it were, reproduce the plastic foreground of those panoramas with their anecdotal form and the extensive background of the panoramas with their store of information.”3 This so-called panoramic literature dated roughly from the early July Monarchy (1830) until about 1845, peaked around 1840–42 as the above advertising suggests, and comprised a number of texts featuring nonfiction observations on urban life written by well-known and obscure authors alike. These authors, and especially their publishers, adopted strategies—both formal and promotional—to capitalize on current trends and appeal to as wide an audience as possible. The panoramic literary texts serve, then, as one of many examples of the successful ways products were packaged and sold to France’s growing readership during this early moment of mass culture. Their manifest hybridity and self-conscious commerciality also help to underscore explicitly the formal and promotional tactics with which the other authors (and publishers) I explore in this book experimented in order to comprehend, master, and profit from contemporary popular and critical tastes.

Panoramic Literature in Context

Panoramic literary texts were varied and came in different formats. Nineteenth-century literary dictionaries and catalogues seemed unable to classify them uniformly, as we will see, an inability that suggests a hybridity or blurring inherent in the genre. The physiologies, for example, were short studies of urban social types that were inexpensive to purchase, made for quick and easy consumption, and resembled a sort of humorous biological or ethnographic study. They were published by the hundreds, especially between 1840 and 1842, principally (but not exclusively) by La Maison Aubert, a publishing house run by Gabriel Aubert and Charles Philipon that also produced lithographic prints, caricatures, and the well-known satirical journals La Caricature and Le Charivari. The series’ titles, including Physiologie du flâneur, Physiologie de la grisette, and Physiologie du tailleur, evoked the emerging scientific discipline of physiology, and the works themselves mimicked the language of the natural sciences in their classifying of social types.4 Their style was witty, however, rather than scientific, and they focused on specifically contemporary types and mores through vignettes, dialogues, and descriptions.5 Richard Sieburth has pointed out that some of the origins of this genre can be traced to earlier études de moeurs (studies of manners) and satirical journals like La Silhouette and La Caricature (both run, at least in part, by Philipon) that contained comical illustrated vignettes.6 The illustrated Physiologie de la poire, a work published on the heels of Philipon and Daumier’s famous caricatures of King Louis-Philippe as a pear, was not the first work to bear this title: Brillat-Savarin’s 1825 Physiologie du goût and Balzac’s 1829 Physiologie du mariage are often seen as precursors of this subgenre.7 The formulaic nature of these physiologies is reminiscent too of other modes of popular culture being produced at the same time, like vaudevilles, which, Jennifer Terni has noted, “were formulaic and mass produced, and . . . their popularity depended, at least in part, on their formulaic predictability.”8 Although clearly distinct in their formal composition from the vaudevilles, the physiologies nonetheless relied on the use of types and a predictable structure that made them appealing to readers.

There existed pricier counterparts to the physiologies, like La Grande Ville, referred to at times as tableaux de Paris or, as Priscilla Ferguson has classified them more generally, “literary guidebooks.”9 They included the 1831 Paris, ou le livre des cent-et-un (“Paris, or the Book of the One Hundred and One”), authored, as its title suggests, by 101 different writers in an attempt to keep publisher Pierre-François Ladvocat’s business afloat; the 1839–42 Français peints par eux-mêmes (“The French Depicted by Themselves”) by the publisher Leon Curmer; and numerous works called new or “nouveaux” tableaux de Paris, referencing Louis-Sebastien Mercier’s Le Tableau de Paris.10 These works could be purchased in installments or as elegantly bound editions and were usually geared toward a middle-class public.11 The larger volumes were similar to the physiologies in their episodic depiction of everyday urban phenomena (types, events, places, professions), yet they were less prescribed in their format. The chapters in these works varied—at times as a result of their different authors—and could take the form of a short story, a dialogue, an essay, or straight typological description, as in the physiologies. Affirming that the “panoramic text uses clearly differentiated genres to represent differing social species,” Margaret Cohen has termed this characteristic of panoramic literature “heterogenericity.”12 The more expensive examples of panoramic literature, then, as opposed to the more fixed physiologies, were models of hybridity in their generic composition, and nineteenth-century cataloguers and bibliographers alike recognized this blurring of generic boundaries.

Much of the commercial success of these works can be attributed to their humorous style and appealing illustrations and, to be sure, the careful publicity campaigns by their publishers. Scholars have argued that these panoramic literary texts enabled readers to navigate and comprehend changing urban spaces and social categories.13 Such mises en types (“rendering as types,” Judith Lyon-Caen’s term) sought to classify and understand cultural codes and types during a moment of great social and political upheaval. Lyon-Caen in particular sees connections between panoramic literature and contemporary social investigations, or enquêtes sociales, works on public hygiene and prostitution.14 For her, “littérature panoramique et romans et enquêtes sociales de la monarchie de Juillet forment ainsi un voisinage textuel qui brouille les frontières de genres et de registres.”15 Meanwhile critics like Karlheinz Stierle locate in the subgenre of the tableaux de Paris the origins of Baudelaire’s theories of modernity.16 In addition to exposing the inner workings of the dynamic literary marketplace, this short-lived phenomenon demonstrates both proto-sociological and literary significance, despite its superficially lowbrow pretentions.

Benjamin’s notion of panoramic literature as a “petit bourgeois genre virtually devoid of genuine social insight,” the textual equivalent of the painted panoramas, has long been accepted as the critical model for analyzing this body of work.17 Recently, however, Martina Lauster, Nathalie Preiss, Valérie Stiénon, and other scholars have encouraged specialists to push past the almost universally accepted Benjaminian understanding of the physiologies and the larger collections of tableaux. Lauster argues that Benjamin’s approach, which views the physiologies and other sketches as part of a “middle-class attempt to gain control over a threatening social body,” ultimately obscures “the dynamism of the text-image relationships which makes the [p]hysiologies the most advanced journalistic meta-medium of the time.”18 Likewise Preiss and Stiénon resist the totalizing vision of Benjamin’s panorama because, they write, the physiologies “privilègient l’écriture non du fragment mais de la fraction et du fait détaché, nulle totalité.”19 Stiénon suggests even looking to the model of the kaleidoscope rather than the panorama for a visual analogy for these texts.20 While I employ the term “panoramic literature” for ease of reference, I align my thinking with that of recent critics for whom these texts are more ambiguous and dynamic than initially characterized by Benjamin.

These panoramic literary texts may have achieved commercial success for many reasons, such as their “proto-sociological” attempts to render contemporary Parisian society legible to their readers, their embodiment of mid-nineteenth-century French readers’ taste for urban observations, their high-quality illustrations, and their humorous tone, among other reasons.21 They also clearly exposed the complex changes taking place in the new literary marketplace. The advertisements for and content of these panoramic works show the developing influence of publishers on their authors.22 Publishers produced and publicized these trendy works; authors too took advantage of popular tastes to capitalize on the trend. If the packaging and advertising of these works call attention to themselves as, in Richard Sieburth’s words, “commodities destined for mass consumption,” the phenomenon of panoramic literature is at once indicative of early mass culture and conscious of the tensions that arose from nineteenth-century popular tastes.23 The frequent evocation of the notion of literary value found in many of these texts shows the panoramic literary works staging contemporary debates about the tensions between high and low literature. Moreover the consistently mixed categorization of these works in book industry publications and dictionaries demonstrates panoramic literature resisting generic conventions and suggesting more generally the fluid boundaries of the literary field in which they were produced. What follows is a close analysis of the panoramic texts themselves, in particular Physiologie des physiologies and de Kock’s La Grande Ville: Nouveau tableau de Paris, and the promotional materials associated with them, as well as an examination of their classification in the Bibliographie de la France. Where previous critics have deemed them “innocuous” and a “nearly perfect example of that transformation of book into commodity,” I will show, through an examination of the content and promotion of these works, that their rapid popularity and commercial success embody, perhaps more overtly than other best sellers of the period, not just the merchandising of literature but also the intricate developments in marketing, publishing, and even literary form taking place in this dynamic new marketplace.24

Physiologie des Physiologies

The Physiologies were a self-consciously commercial series; they were essentially marketed both from the inside and the outside of the text. In order to understand the way the physiologie series exposed the inner workings of the marketplace for popular literature, it is helpful to comprehend fully the form and content of this peculiar subgenre. The 1820s saw the publication of occasional texts, unrelated to the scientific study of physiology, which bore the title Physiologie (notably by Brillat-Savarin and Balzac). But during the real boom of their production (1840–42) an estimated 130 were produced, and they sold by the thousands.25 What is notable about these texts is their uniform structure: “C’est la constance du même format in-32, du même nombre de pages (une centaine environ), le même prix, 1 franc, prix relativement bon marché à cette époque.”26 Though comical in nature, these typological studies, as we have seen, functioned in multiple ways: to render the city readable, allowing readers a chance to master their chaotic urban space; to ironize the notion of the great writer; to ape the language of scientific discourse; to categorize urban phenomena; and to respond to the market’s desire for hypercontemporary literary works that depicted their readers’ everyday lives.27

Take, for example, arguably the most famous instance of the genre, Physiologie du flâneur by Louis Huart, a frequent contributor to the genre. The text begins, with mock philosophical pretentions, by disproving previous definitions of man so as to redefine him in the following way: “Un animal à deux pieds, sans plumes, à paletot, fumant et flânant.”28 What characterizes man, according to this text, is his ability to “perdre son temps.”29 The next several chapters explain how to discriminate the legitimate flâneur from others, prove how the flâneur is fundamentally a moral creature (so empty is his mind that he is incapable of thinking immoral thoughts), and demonstrate how to distinguish among the subgenera of flâneurs (from the “flâneur parfait” [perfect flâneur] to the “flâneur militaire” [military flâneur]). The narrator explains the pleasures and inconveniences of flânerie (enjoying colorful signs posted throughout the city; getting thwacked by shutters put out inattentively by shop workers anxious to close up), notes the typical urban spaces in which the flâneur circulates, and finally offers helpful hints to new flâneurs, including useful vocabulary. Huart breaks down the characteristics of this specific urban type while humorously mimicking philosophical and scientific discourse. This example illustrates the physiologie’s fixed format and style despite variations in subjects across the series, a purposeful standardization “par les impératifs éditoriaux de collections destinées à fidéliser un lectorat et à susciter des effets de modes.”30 By 1841 the genre was so popular that an anonymous author published Physiologie des physiologies, a parody of an already parodic text.31 Reading this work gives insight into the style and format of the genre and also into the way these works were understood at the time of their publication as a commercial genre that highlighted tensions about literary value.

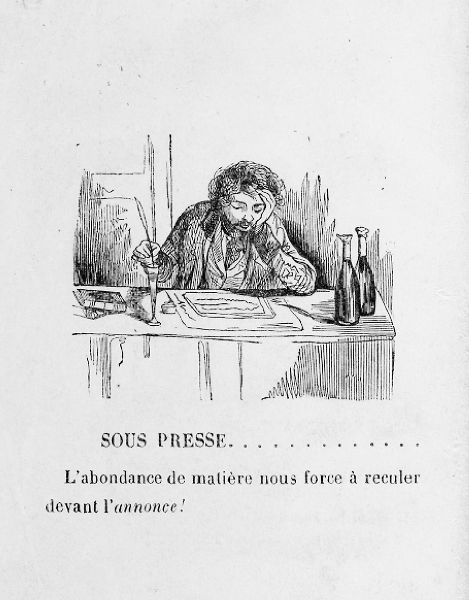

Fig. 2. Back cover of Physiologie des physiologies (1841). Bibliothèque Nationale de France.

On the back cover of Physiologie des physiologies there is a sketch of a tired or even jaded writer, his head resting on one hand as he dips his quill into the ink with the other and stares dazedly at the text before him, where several squiggles are drawn but no letters are distinguishable (fig. 2). Below this sketch, which is not attributed to an artist but resembles the work of Gavarni and other well-known illustrators of the Physiologie series, in bold type is written the following: “SOUS PRESSE. . . . L’abondance de matière nous force à reculer devant l’annonce!”32 This cheeky statement occupying the place that ordinarily offered a list of forthcoming or available texts—and most often physiologies—along with the image of the blasé writer work in concert to capture the content of the text that has preceded this back cover. The sheer number of physiologies published then and in the previous year, and the almost obligatory need for all authors to produce one of these short texts, are treated in depth in this satirical physiologie, a tongue-and-cheek analysis of the ongoing trend.

Physiologie des physiologies begins with a seven-stanza poem that also functions as a summary of what is found in the subsequent text. From the start the author evokes two commonplaces of the physiologie genre: that all authors think themselves capable of writing a physiologie and that the texts are hastily cobbled together:

La mine est féconde

Se dit à part soi tout bas,

Chacun à la ronde

Avant de sortir d’ici

Je m’en vais bâcler aussi

Ma Physiologie O gué! Ma physiologie.33

In addition to the use of the term bâcler (to botch or dash off), the ease with which the physiologies are produced is repeated when the poet describes the writing process as “une oeuvre en quelques instants est toute finie” and, in a longer passage, explains, “Qu’on me donne seulement . . . de l’encre et du papier blanc, et je vous parie / que sans gêne avant demain / je mets tout le genre humain / en physiologie.”34 Ruth Amossy suggests that this song attests to the fact that “le mérite essentiel de ces petits livres est de s’écouler facilement sur le marché.”35 Not only do all writers feel the need to create their own physiologie, but all readers are desperate to read them and to see themselves recognized in them; this need for familiarity motivated not only the writers of panoramic literature but also novelists like Eugène Sue to focus on the urban subject. Likening the short texts to “champignons après une pluie” the poet writes that “chaque homme voulut avoir sa physiologie.”36 The poet also addresses the extreme popularity of these most modern of texts, comparing them to the satirical review Les Guêpes and a larger panoramic literary text currently being published, Les Français peints par eux-mêmes, but suggests that these two publications “ne font plus furie” and that “les lecteurs en ont assez, leur veine est tarie.”37 Instead it is the age of the physiologie: “Vive en ce jour heureux la physiologie.”38 In a dynamic market where need for the newest and greatest product grows daily, the physiologie subgenre is the latest trend to surpass these others. Both the introductory poem and the paratextual material at the back emphasize the popularity and prevalence of these works as a way, it seems, to sell more; they build on the commercial phenomenon of the physiologies to advance it.

Throughout the remainder of the work, all of these themes (the facility of writing physiologies, their omnipresence in the marketplace, their questionable value) are developed at length, indicating engagement with the pressing tensions in the evolving literary field. The author comically cites both the scientific and literary pretentions of these trendy works, noting, “Grâce à ces petits livres, pétris de science et d’esprit, l’homme sera mieux classé, mieux divisé, mieux subdivisé que les animaux ses confrères,” and also states that to create a physiologie one must simply mix together some simple ingredients, like following a recipe: “Prenez une pincée de Labruyère—une cuillerée des Lettres Persanes. Faites infuser les Guêpes; Les Papillons noirs; Les Lettres Cochinchinoises; La Revue Parisienne; les Nouvelles à la main; Mettez à contribution les feuilletons du Corsaire et du Charivari”; wrap it all up in “des Français, inventés par M. Curmer” and the product is complete.39 According to Stiénon, this recipe, composed of “ingredients de base, plutôt faciles à trouver,” is one of many examples of the genre’s “moquerie du créateur incréé,” the puncturing of the image of the “genie créateur”; in other words, it gestures toward critical debates surrounding the production of literature, in particular of industrial literature detailed most notably just two years earlier by Sainte-Beuve in his essay “De la littérature industrielle.”40 This parodic text reiterates commonplaces about the dual nature of such works: on the one hand they are pseudo-scientific and even early sociological tracts; on the other, they are deeply involved in a literary conversation—even from the margins.41

The text speculates as to why these short works have become so popular, once again underscoring their overt engagement in contemporary questions about literary value and commercial literature. In fact it keenly offers one explanation that Lyon-Caen has recently developed: that contemporary readers enjoyed works that depict recognizable types. The text twists this logic a bit in arguing that “chacun croit y reconnaître le portrait de son voisin, et en rit. S’il se reconnaissait lui-même, il crierait au scandale. Voilà pourquoi chacun attend avec impatience sa Physiologie. . . . Afin de reconnaître son voisin et de s’en amuser, sans jamais se reconnaître soi-même.”42 Readers are familiar enough with the types comically described within that they enjoy recognizing their neighbors (but not themselves), and they eagerly anticipate subsequent publications. This is not the only passage of the work to poke fun at its readers—or its writers. The text offers the following “definition” of physiologie (these “definitions” are common features of the genre): “Ce mot se compose de deux mots grecs, dont la signification est désormais celle ci: Volume in-18; composé de 124 pages, et d’un nombre illimité de vignettes, de culs de lampes, de sottises et de bavardage à l’usage des gens niais de leur nature.”43 Replete with silly tales and typographical ornamentations, these small texts target “simple” readers, or so the Physiologie posits.

The anonymous author further (humorously) maligns the genre by comparing it to the work of the supposed founder of the physiologie trend (Brillat-Savarin, with his 1825 Physiologie du goût) and chiding him for the fact that he showed “tant d’esprit et de délicatesse de son temps” and therefore calling attention to the supposed poor literary quality of the physiologies.44 The problem is, he explains, that today’s writer prefers not to imitate the “high quality” writing of Brillat-Savarin and has thus never “si bien réussi à s’éloigner du maître.”45 Although the works share the same title of Physiologie, simply turning the page reveals serious differences between the two: “Dans l’un, l’esprit le plus gai, le plus fin, le plus charmant, le plus exquis; Dans ceux-ci, l’esprit le plus lourd, le plus épais, le plus fastidieux, le plus grossier.”46 The author highlights the reductive nature of the genre—“Le volume entier est sur la première page”—and even offers a mock physiologie de l’homme mort to parody the genre.47 These works, we are meant to understand, are both simple to write and to read, can be quickly thrown together, and are enjoyed by a large audience. In characterizing the genre in this fashion, the author repeats many contemporary and modern commonplaces about its style and quality. These witty barbs about the quality of the questionable literary value of the physiologie can be found throughout the series, not only in this parodic text. In focusing on what she calls the “dimension autoréflexive” (self-reflective dimension) of the physiologie, Stiénon notes in particular its tendency to call attention to the inferior literary quality of the works: “Ces monographies s’autodéfinissent comme illégitimes à travers une écriture qui exhibe volontiers leur statu de textes mineurs, faciles, voire de piètre qualité.”48 They enter, in an explicit way, into the contemporary debate about the literary value of commercialized literature.

However, while Physiologies des physiologies does focus on the conventions about the facility of writing in this genre and the stereotypes about its readers, it is also at pains to describe the prevalence and commercial success of the genre, despite what the author critiques as its inferior literary qualities; as such, Physiologie des physiologies can be said to be marketing itself, and the series as a whole, from within the work itself. Over and over again the author repeats that the physiologies are in demand and taking the literary marketplace by storm. There is, for example, the short chapter entitled “Physiologies—Physiologies, et tout est physiologie” in which the author claims that “un livre sérieux aujourd’hui, c’est un non sens,” before staging a scene in which the reader enters a bookstore and is confronted with the choice of which book to purchase.49

Voyez pluôt—Vous entrez chez un libraire, et vous lui demandez un bon livre.

Que fait le libraire?

Il vous offre une Physiologie.

Vous repoussez cela du doigt avec mépris et vous avez raison—Mais regardez autour de vous;

Parcourez d’un regard tout le magasin de votre libraire. Où sont donc Molière, Racine, Corneille, Montesquieu, Fénelon, Chateaubriand, Lamartine, Hugo? Là-bas, tout au fond dans l’ombre. Ils dorment, en attendant la résurrection. Mais qu’est-ce que donc que tous ces petits livres, jaunes . . .—bleus,—rouges,—qui se présentent pêle-mêle dans les rayons,—qui encombrent les tables jusqu’au plafond, et dont les longues files se roulent.—s’enroulent et se déroulent comme d’énormes serpents aux écailles changeantes? Physiologies, Physiologies,—et tout est Physiologie!50

While disparaging the quality of the physiologie as opposed to the work of other contemporary and classical writers, the author nevertheless depicts these other writers (both literary greats of seventeenth- and eighteenth-century France as well as contemporary romantic heroes) as being in retreat, waiting out the phenomenon of the physiologie. The shadow cast over these more critically accepted works is contrasted with the flashy colors of the physiologie, which seem to take over the tables of the bookstore. Even if the reader prefers to buy a work by Molière or even Hugo, the bookseller will push him to buy a physiologie. This depiction implies both that the popular texts overshadowed all other available works on the market and also that the never-ending supply of these texts offered all the more incentive for booksellers to push them on their clients. Further still, the author (comically to be sure) claims that his appetite has only been whet by the available physiologies—“Vous n’avez fait qu’aiguiser notre soif”—and ends the book with a list of subjects for possible future physiologies, entreating his fellow authors to write and promising financial gain: “Vous serez béni par les cordonniers, les chapeliers et les gantiers—ce qui est beau; et vos réclames seront grassement payées,—ce qui est mieux.”51

In the end both the content and the material surrounding Physiologie des physiologies offer insight into the understanding of the genre in the moment that the phenomenon was playing out. On the whole the physiologies were very self-conscious about their style and commercial nature, and this particular work—distilling all of the genre’s qualities into yet another cheaply formatted (in-32) 124 pages—calls attention to all the genre’s characteristics. Denis Saint-Armand and Stiénon view Physiologie des physiologies as the culmination of the genre, calling it a “texte contre-programmatique,” and highlighting the tendency of the genre to contain a metacommentary regarding “sa médiocrité, sa facilité, ses visées commerciales.”52 This parodic work, in other words, takes to the extreme the physiologies’ already explicit awareness of their relationship to the literary field. Saint-Armand and Stiénon remind us too that this 1841 text was not without precedent.53 On October 11, 1840, slightly earlier in the success of the short phenomenon, La Caricature, a journal that was run out of La Maison Aubert, published an anonymous article also entitled “Physiologie des Physiologies” that took up many of the same themes and repeated some of the same language as the 1841 physiologie. The article called attention to the scientific origins of the term, before citing Brillat-Savarin as the founder of the nonscientific version of the genre and finally giving the most “modern” definition of it: “La physiologie est l’art de parler et d’écrire incorrectement, sous la forme d’un petit livre vert, bleu, rouge, jaune, qui fait de son mieux pour soutirer une pièce de vingt sous au passant, et qui l’ennuie tout son saoul en retour.”54 In chapter 4 I will produce a similar version—almost verbatim—of this quotation attributed to Balzac in his Monographie de la Presse parisienne, indicating a certain amount of recycling in the critical discourse about these texts as well as in them, a trait so characteristic of the repackaging of language and genres during this period. Notable in La Caricature’s article, however, is the consistent reference to the poor quality of these prolific and cheaply sold texts. Further recycling from this piece to the Physiologie can be found in the “recipe” this article offers for creating a physiologie: “Vous remplissez cela de fadaises, bons mots, balivernes, gaudrioles, anas, coqs à l’âne, sornettes, chansons . . . vous semez le tout de solecismes, jurons. . . . Vous copiez sur la couverture les Guêpes ou la Revue parisienne . . . et vous servez chaud.”55 Though the steps for concocting physiologies are slightly modified here, the references to contemporary publications and the format of this list are quite similar and reinforce the elements of this subgenre that would be crystalized shortly after in Physiologie des physiologies. This was a fixed and digestible literary format whose possible topics were virtually infinite; in sum, the recipe laid out by the Physiologie’s anonymous author was one that promised commercial success.

Aubert’s Market for the Physiologies

Between 1840 and 1842 it was primarily Philipon and his brother-in-law Gabriel Aubert who cornered the market on the short, abundant physiologies. Aubert and Philipon’s joint publishing venture, La Maison Aubert, maintained “absolute dominance of the city’s trade in les physiologies.”56 While other publishers tried their hand at the genre (Desloges and Bocquet, to name two), according to Lhéritier, “Aubert, surtout par la qualité de ses illustrations, s’imposa comme le véritable éditeur des physiologies.”57 Between February 1840 and August 1842 La Maison Aubert produced thirty-two physiologies “in a combined edition of 161,000 volumes or just over three quarters of the total number of such volumes published in Paris during this period.”58 La Maison Aubert, in other words, profited most from this ephemeral yet lucrative phenomenon. Lhéritier goes as far as calling Philipon the true creator of the particular “genre physiologique”: “Il semble bien que les physiologies, telles qu’elles ont été présentées au public, sous petit format et illustrées de nombreuses vignettes soient nées d’une idée de journaliste. L’invention en revient à Philipon . . . et de toutes les productions de la maison Aubert.”59 Whether or not the genre was the brain child of Philipon, it is clear that La Maison Aubert’s publications made up the majority of those sold during this short window and that this enterprise took advantage of its experience with and knowledge of the marketplace to dominate and capitalize on the trend. Attention to their publicity campaign, one that keenly seized on market trends for the panoramic literary genre and that would eventually define the brand of the Aubert physiologie, evinces the publishing house’s use of more modern marketing tactics.

Reasons for the success and volume of La Maison Aubert’s series certainly included the existing trend for its satirical, illustrated publications, but its connections with the network of popular publishers, authors, and illustrators, and Philipon’s evident understanding of the market, cannot be discounted. Even in the early years of his career, Philipon was actively producing works in line with current trends. Prints attributed to Philipon from the late 1820s “were the gently erotic kind so popular among bourgeois Parisians in the final years of the Restoration.” Having opened his own printing shop in 1830, Philipon continued to publish such prints as well as political caricatures, cannily tapping into the market of the “many print genres that had in common a bourgeois market defined by the commercial culture of the city’s Right Bank quarters centered on the Palais Royal.” As the popular press began to take hold in Paris, Philipon became involved as one of the shareholders of the new journal La Silhouette in 1829 alongside other key figures of the time like Emile de Girardin (who founded La Presse) and the journalist and publisher Charles Latour-Mezeray. When he started his own satirical journal, La Caricature, in the following years, Philipon “brought to the task not only the valuable administrative and financial experience in the publication of such a journal but also the knowledge of its potential market that must have been relayed to him by his fellow shareholders, all of whom were journalists central to the development of the Parisian popular press.” Around the same time Philipon was establishing himself as a preeminent figure of the satirical press, he also joined forces with his brother-in-law and opened La Maison Aubert, a “magasin de caricatures” located, tactically, in the “center of the city’s trade in prints and caricatures,” the Passage Véro-Dodat. Geographically and professionally Philipon had secured a commercial space that would assure him success.60

In 1832 Philipon founded Le Charivari, another daily satirical journal. Available by subscription like La Caricature, Le Charivari differed in price, content, and target audience from the previous paper. La Caricature appeared less frequently and was printed on a higher quality paper for more wealthy readers.61 Both papers, which Philipon controlled, were produced out of Aubert’s shop, and Aubert was compensated for the use of this space. In 1835 La Caricature folded due to new legislation, so Philipon could pour more resources into Le Charivari. Though other newspapers began to include caricatures in their pages, Philipon—with the advent of these two newspapers—was able to “to foresee the potential success of the illustrated satirical journal and to marshal the necessary financial backing to make a go of it in the early years of the July Monarchy.”62 The portrait of Philipon that emerges is of a savvy and well-connected businessman who, as a practitioner and publisher, had an excellent sense of the tastes of readers for light, satirical illustrated texts.63 With his knowledge of the trade and comprehension of the medium, he was poised to contribute to and profit from the popular literary trend of panoramic literature.

By the time of the phenomenon of the physiologies, La Maison Aubert had moved to the Bourse, marking (symbolically, according to Cuno) “the transformation of Philipon’s publishing enterprise from one that was struggling, politically contentious, and laden by fines and seizures in the early 1830s to one that was highly successful, commercially diversified, and politically acceptable in the 1840s.”64 At this point Philipon had honed many of his marketing and sales tactics. According to Lhéritier, in the Charivari, “on y rencontre souvent, à la dernière page, des annonces pour la collection Aubert et parfois des pages entières reproduisant des vignettes extraites de physiologies.”65 Taking advantage of the free advertising space, Aubert’s publishers often placed ads or réclames (paid advertisements masquerading as articles) for the physiologies within the pages of the Charivari as well, a strategy we would call owned media today.66 These ads also appeared readily from 1840 to 1842 in the daily political papers, notably La Presse, whose founder was the former co-shareholder of La Silhouette with Philipon. Many of these ads, on which I will linger here briefly, highlighted the exclusivity of the Aubert brand, the famous nature of the authors and illustrators of the series, and the sheer quantity of physiologies being produced; at the same time they illustrate the keen marketing tactics of La Maison Aubert.

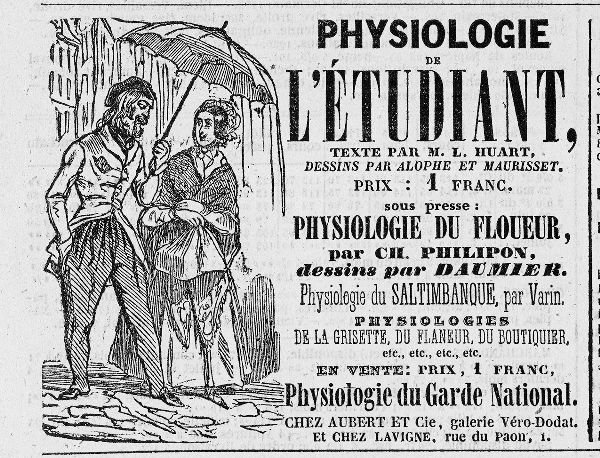

If we track the ads for the Physiologie-Aubert over the short period of 1841–42, we can see the literary phenomenon of the physiologies developing in real time and Aubert’s response to this phenomenon in his publicity. In particular, ads from early in 1841 compared with ones in late 1842 show just how prolific these texts became over such a short period and how La Maison Aubert sought to corner the market on them. An ad on April 14, 1841, for the Physiologie de l’étudiant by Huart, for example, boasts an illustration of a young man holding an umbrella for his female companion and the word l’étudiant in a large, bold type, much larger than the word physiologie (fig. 3). The low price of the volume (“1 franc”) is centered below the title and author’s name, and under the price is a list of six other titles, each in different fonts, the variety of which suggests a lack of cohesion among the volumes despite their common title. On one line of the advertisement, however, the titles of a few works are grouped together—“Physiologies de la Grisette, du Flâneur, du Boutiquier”—and the ad also includes the string “etc, etc, etc, etc,” which gesture toward the eventual collection Aubert would advertise and the forthcoming surfeit of physiologies.67 In other words, although La Maison Aubert was actively selling and publishing physiologies at this moment, the volumes had not yet become enough of a phenomenon to advertise them as such.

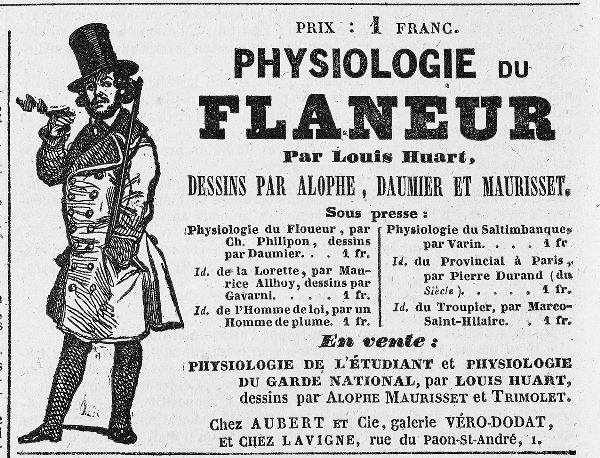

No more than one month later La Maison Aubert had ramped up the rhetoric surrounding the profusion of physiologies in its advertisements. In a réclame placed in the May 18, 1841, issue of La Presse, the now well-known Physiologie du flâneur by Huart was advertized by his publishers as continuing “la piquante collection de volumes in-18, entreprise par MM Aubert et comp., qui mettent sous presse la Physiologie de la Lorette, celle du Flâneur, du Boutiquier, du Saltimbanque, et un grand nombre d’autres petits ouvrages du même genre”(fig. 4).68 Aubert had begun to sell the physiologies as individual works and as a collection; as part of his advertising strategy, it seems, his ads now indicated the forthcoming works, as well as already published ones. As if to confirm this approach, below the réclame is an ad for the Physiologie du flâneur that is visibly more streamlined than the May 14 ad. A sketch of the flâneur occupies the left quarter, and the title, centered under the words “Prix: 1 franc,” contains the word “FLANEUR” in large boldface. The title hovers above a two-column list of titles “sous presse,” which in turn is positioned above a list (in smaller type) of those works currently for sale. All of these titles are printed in a relatively similar font—as opposed to the varied fonts in the May 14 ad—giving a sense of uniformity among the works and indicating, by extension, that the genre had begun to coalesce.

Fig. 3. Ad for Physiologie de l’étudiant in La Presse, April 14, 1841. Bibliothèque Nationale de France.

Fig. 4. Ad for Physiologie du flâneur in La Presse, May 18, 1841. Bibliothèque Nationale de France.

Later that year La Maison Aubert’s ads show the publishing house defining its brand against those produced by other publishers by highlighting their quality as well as the popular illustrators and authors who contributed to the collection. Though one might assume that the influx of physiologies by other authors could only contribute to the popularity of the genre and thus to sales of Aubert’s works, by the end of 1841 the publishing house evidently felt the need to distinguish itself from the others and to establish itself as the founder of the genre. The back page of the August 14, 1841, issue of La Presse contains promotional material for Balzac’s Physiologie de l’employé in the form of a réclame and an advertisement. Highlighting the quality of Balzac’s work, the réclame states, “C’est le plus fécond de nos romanciers, M. H. de Balzac, qui a bien voulu se charger de décrire l’employé, et nul ne pouvait mieux le faire” before claiming, “Cette collection de petites physiologies est supérieure à toutes celles qui paraissent aujourd’hui.”69 By banking on the established reputation of Balzac and his incomparable work on this physiologie, the ad differentiates itself from the other physiologies by calling Aubert’s collection, and its contributors, superior. A November 24, 1841, ad that promoted a variety of works produced at La Maison Aubert included publicity for the Physiologies-Aubert brand, noting, “Il ne faut pas confondre cette jolie publication avec la foule de mauvais petits livres que son succès a fait naître.”70 Similarly a réclame in the May 28, 1842, issue of La Presse announced the sale of Philipon’s own Physiologie du floueur, completing “la collection de 25 jolis petits volumes qu’on désigne sous le titre de Physiologie-Aubert, pour la distinguer de cette foule de petits mauvais ouvrages que son succèss a fait naître.”71 The physiologie was the creation of Aubert, we are to understand, and all others were not only imitations but inferior ones at that. Additionally we see Aubert’s repackaging of the individual physiologies into a complete collection; he has shrewdly created a new product out of an existing one—the collection in place of the individual, less expensive physiologies—thereby further extending the Aubert brand.72

Fig. 5. Ad for La Maison Aubert’s Physiologie series in La Presse, March 12, 1842. Bibliothèque Nationale de France.

Perhaps the zenith of Aubert’s physiologie publicity came in the form of an ad in La Presse on March 12, 1842, that covered over a third of the back page (fig. 5). “PHYSIOLOGIES-AUBERT” runs across the top in block letters, flanked on either side, as had become customary, by the price: “Prix: 1 FR le volume.” Underneath we read that the complete collection is available in twenty-five volumes, with illustrations from Gavarni, H. Monnier, and Daumier, among others. To underscore the quality of the volumes’ illustrations, the publisher has included six sketches—one, for example, of a man working at his desk to correspond with Balzac’s Physiologie de l’employé. The large number of sketches is a nod to the trend for caricature and also a reminder of the famous illustrators associated with the physiologies and Aubert more generally. Among the illustrations, the ad includes blocks of text containing titles and authors (“Physiologie de l’employé par de Balzac”; “Physiologie du bas-bleu par Frédéric Soulié”; “Physiologie du bourgeois, par Henri Monnier”). Twenty-four works are listed, and “Idem” replaces the word “Physiologie” for all but the first title in each column, reinforcing the sheer number of installments. Although no particular author is highlighted (as was the case in the previous ad for Physiologie de l’employé), the names of many of these authors—de Kock, Soulié, Huart, Balzac—should be enough to compel readers into purchasing the complete collection, even if they are less familiar with the other authors.73 The twenty-fifth volume in the collection is listed along the bottom of the ad as being “sous presse.” It is Physiologie du floueur by none other than Charles Philipon himself. The boldface text runs along the bottom of the ad, bringing to a close both the Aubert collection and the ad itself. This large advertisement encapsulates the phenomenon of the physiologie at the peak of its popularity: it highlights the trendy, well-known artists and their contributions to the series; it repeats and foregrounds the low price; it reinforces the abundance of these short texts by including a list of all the available titles; and without saying so explicitly, as some of the réclames do, it emphasizes the exclusivity of the Aubert brand by the size of the title’s print, the cachet of the names associated with the collection, and, ultimately, with the inclusion of one of Philipon’s own physiologies.

A more scaled-down version of this large ad appeared in subsequent issues throughout mid-1842, but at this point ads for and even references to the physiologie collection became scarce in La Presse and other newspapers. Aubert’s name still remained a frequent fixture for his other albums and collections, but the fad for the short typological texts declined. Their popularity seems to have run its course. In fact the lack of advertisements for the Physiologies-Aubert speaks once again to La Maison Aubert’s keen manipulation of the marketplace; no longer was it deemed profitable to promote a product that was unlikely to sell as well. Philipon and Aubert worked at the beginning of the market for advertising.74 Analysis of their ads shows a shrewd understanding of the new tools for producing and selling texts and offers insight into the brief but successful run of these short volumes, in particular those of the Aubert brand.

Their promotional strategy was just one of many factors contributing to the predominance of La Maison Aubert’s physiologie series. In fact the physiologies themselves actually served as a vehicle for their own advertising. Huart’s Physiologie du flâneur contains an illustration of multiple clients crowded in front of the Aubert shop front and a close-up of a flâneur intently gazing at the caricatures in the window, so engrossed that he does not realize he is being pickpocketed. It also includes a written description of the riveting storefronts of “Susse, Martinet et Aubert,” which, he claims, unwittingly engender the success of Parisian pickpockets: “Il est très difficile d’avoir les yeux à la fois sur une caricature et sur sa poche.”75 The narrator incorporates a reference to La Maison Aubert for the accuracy of his depiction of modern Paris but also to promote the business that will subsequently sell and distribute this very text.76 For Stiénon and Saint-Amand, this image is typical of the series’ references to the texts’ own commerciality: “Surcodant leur lisibilité selon les modes de consommation d’une certaine littérature, ces textes insistent sur les mentions que livraient les cabinets de lecture et les boutiques les diffusant.”77 While La Maison Aubert’s series were not the only contributors to the genre, their commercial success and visibility testify to Philipon and Aubert’s capacity to tap into the market for this in-demand product, as well as to their skill in promoting the physiologies by using their already established network of artists and clients.

Nouveaux tableaux de Paris

The larger, multi-authored texts known to some as the “tableaux de Paris” differed from the physiologies in their price and format and through their form, content, marketing, and reception exposed explicit comprehension of their status within the literary field. Indeed Philipon and Aubert were not the only publishers to capitalize on the trend of descriptions of modern Parisian phenomena. Well before the craze of the physiologies, a similar but larger text was orchestrated as a commercial venture. In 1831 Paris, ou le livre des cent-et-un was produced as a “collective serial” and was “meant to be a lifeline for the publisher Ladvocat whose publishing house . . . was facing ruin. . . . Over one hundred contributors came together . . . to launch a lucrative publishing project that plugged the gap in the market between books and journals.”78 The book included an introduction by the well-known journalist and critic Jules Janin, followed by individual chapters on wide-ranging urban topics. These highly contemporary depictions, or “sketches,” as Lauster calls them, “together with ‘hundreds’ of other sketches, provide[d] a total picture, a ‘tableau’ or ‘physiognomy’ of the city.”79 For Cohen, it is Paris, ou le livre des cent-et-un that “inaugurated” the trend of “collections of descriptive sketches of contemporary Parisian life and habits.”80

Though numerous collective volumes appeared in the years following the Cent-et-un, the subsequent best-known collection was Les Français peints par eux-mêmes, published by Léon Curmer (known for his ornate illustrated editions) between 1839 and 1842, which announced itself as the “encyclopédie morale du XIXe siècle.” Almost a decade after Ladvocat’s collective work, according to Jillian Taylor-Lerner, “Curmer secured the collaboration of over one hundred writers and artists, soliciting as many celebrity contributors as possible, but also, remarkably, inviting submissions from aspiring amateurs and local informers.”81 Like La Grande Ville, Les Français could be purchased in different formats of varying prices: “in serial installments for thirty centimes, in softcover volumes for fifteen francs, or in more expensive hardcovers of colored cardboard or gilded leather.”82 Before and during the boom of physiologies, publishers took advantage of the (arguably manufactured) taste for urban observation to arrange these larger, collective high-value publications.

While the examples of Ladvocat and Curmer have been studied at some length by other critics (such as Lauster, Cohen, and Taylor-Lerner), relatively little attention has been paid to de Kock’s La Grande Ville: Nouveau tableau de Paris. It resembles the previous collections of “sketches” in physical composition and in the formats in which it was sold and marketed, but volume one of La Grande Ville differs from its predecessors by being produced by a single author. A second volume followed quickly in 1843, collecting the work of heavyweights such as Balzac and Alexandre Dumas père, in addition to popular writers and journalists such as Soulié and Edouard Ourliac.83 While de Kock’s work may have represented a less explicitly orchestrated editorial project, it nonetheless exemplified many of the characteristics of the large-scale urban panoramic texts. A close examination of de Kock’s La Grande Ville, a work published after many of the other collected works but still during their popularity, shows the author honing in on and perfecting the qualities that had made his predecessors commercially successful while also revealing a distinctly literary approach to his subject. In this new era in which authors made their living from writing instead of being sponsored by wealthy patrons, La Grande Ville offers one example of the trend of the tableaux de Paris that dominated the contemporary marketplace.

The publisher’s prospectus of de Kock’s La Grande Ville: Nouveau tableaux de Paris touted this 1842 work as “un ouvrage d’une telle importance, écrit par le romancier le plus populaire de notre époque,” specifying, “Ce n’est point un roman, ce ne sont pas non plus de simples tableaux: c’est une immense comédie à cent actes divers. . . . C’est Paris tel qu’il est, tel que Paul de Kock l’a vu, l’écrivain le plus vrai, le plus gai, le meilleur observateur de son temps.”84 This collection of short tableaux depicting different urban phenomena promised readers a sprawling representation of Paris that was both entertaining and faithful by one of the period’s best-known writers. Taking advantage of the author’s fame and reputation, this prospectus uses almost hyperbolically positive descriptions of his skills as an observant, faithful, and witty writer to hype the importance and originality of the work. Other promotional materials for this new work could be found throughout the press surrounding the time of its publication. In an August 30, 1842, issue of Le Charivari, the satirical journal’s usual daily lithograph was replaced with images excerpted from La Grande Ville and a note on the preceding page explained, “Le Tableau de la grande ville, dont les vignettes remplacent aujourd’hui notre lithographie, est un amusant et fidèle panorama de Paris. Il parle à la fois aux yeux et à l’esprit:–aux yeux, par des dessins dus au crayon de nos plus spirituels artistes;–à l’esprit par un récit vif, piquant, animé, tel qu’on devait l’attendre de la plume de M. Paul de Kock.”85 Full of praise for La Grande Ville, this note—likely a paid advertisement—banks on readers’ attraction to contemporary popular artists and to de Kock and repeats the same qualities found in the prospectus: this Parisian “panorama” is both “amusant et fidèle.”86

De Kock’s preface contextualizes the succeeding fifty-two chapters of La Grande Ville in relation to other works on the city, explaining that though many of his predecessors have attempted to make Paris known to their readers, his effort is different. Though he aims to produce a more “modern” depiction than Mercier, De Kock’s narrator, like that of Le Tableau de Paris, will use walking and observing as a means of documenting nineteenth-century Paris, and he playfully invites the reader to accompany him through the streets of Paris, exclaiming, “Promenons-nous au hasard.”87 Assuming the role of flâneur, the narrator will not set up a preplanned itinerary around the city but rather will report on whatever he stumbles upon: a store where one can rent a bathtub, the ubiquitous stands selling galettes (cakes), the sidewalks themselves. The narrator uses a lighthearted tone but takes seriously a number of crucial themes surfacing in literary discourse of the period, ranging from the popularity and difficulty of depicting Paris in a literary work to the concept of realism, the status of the author within the literary text, and the relationship between history and modernity.88 With this light yet richly intertextual preface, de Kock’s narrator sets up La Grande Ville as a consciously literary work, acutely aware of its position in the literary tradition of the tableau de Paris. Although the subtitle of his work offers “comique” as the first adjective in describing the subsequent tableaux of La Grande Ville, the preface establishes its status as a “critique” as well.

La Grande Ville, a mixture of text and image, proves also to be a blend of genres in its structure and content. As noted earlier, “Ce n’est point un roman, ce ne sont pas non plus de simples tableaux: c’est une immense comédie à cent actes divers.”89 The work is made up of fifty-two chapters, a journey through the streets of Paris with an observant guide, depicting a blend of commercial, domestic, social, and recreational spaces, indoor, outdoor, and in-between. The form of each of the narrator’s observations changes shape as often as the Parisian sites he reports on.90 The chapter “Les Révérbères” (The Lampposts), for example, is a concise historical description of lampposts in Paris, from oil lamps to the becs de gaz (gaslights). “La Galette” (The Cake) is journalistic in tone and reports on the newest craze in Paris: where one can find a good galette stand, examples of fortunes earned by opening a galette stand, and how the galette is on par with, if not superior to, other modern inventions, such as the steamboat, the free press, and the moustache. “Les Bains à domicile” (Home-Delivered Baths) takes the form of a short story about a young grisette (young working-class woman) who, furious over her eviction, seeks revenge on her landlord by ordering six bathtubs and enough warm water to fill each of them to be delivered to his home at once. “Les faux-toupets” (The Toupees) instead of describing the advent of the toupee, presents a dialogue between two women—“Écoutez plutôt la conversation de deux jolies dames”—who critique a well-known society man for tricking them into admiring his false locks.91 “Une soirée dans la petite propriété” is told as a moral lesson, a fable in the style of La Fontaine (whom the narrator quotes at the beginning of the piece), on how all people, desirous of what those in the higher classes have, attempt to imitate them at all costs. De Kock’s guide to midcentury Parisian social life is thus a compilation of genres and discourses, from the theatrical scene to the short story, from history and journalism to the fable, all grouped together under the form of a comedy, as the publisher remarks in the preface (written the same year as Balzac’s own preface to his Comédie humaine), but also as a sort of travel narrative of the city of Paris and an étude de moeurs.

In addition to the multiple literary genres that form this hybrid work, close textual readings of de Kock’s social urban guide reveal the author’s literary approach to his subject, in particular the relationship the narrator establishes with his interlocutor throughout this work. De Kock’s debt to Mercier is obvious in his preface, yet he faults Mercier and other writers for including themselves in their prose. De Kock explains, “Il ne faut que décrire ou relater des faits; [le défaut des auteurs] c’est de venir toujours se poser entre le lecteur et le sujet qu’on traite, comme pour lui dire: ‘A propos, n’oubliez pas que c’est moi qui écris cela.’”92 To distinguish himself he almost fully absents himself from the text after the introduction, remarking wittily, “Qu’est-ce que tout cela fait au lecteur, qui s’inquiète fort peu de savoir comment vous est venue l’idée de faire tel ou tel ouvrage, mais qui veut seulement que cet ouvrage l’amuse, l’instruise ou l’intéresse?”93 While the je of the introduction is certainly absent from the fifty-two chapter-length vignettes, one for each week of the year, that compose La Grande Ville, the pronoun vous seems to be the focal point of the guide. De Kock’s narrator has created an extraordinarily varied interlocutor, using vous in a complex and inconsistent manner, even writing the fictitious interlocutor into each of his descriptions of Paris. In the first vignette, “Bureau des nourrices,” vous is an observer of the scene, whose wife has just had a baby and who is unaware of how to procure a wet nurse. Clearly this vous is a bourgeois French male. Throughout the chapters, however, the interlocutor varies in gender, class, and nationality. In the vignette titled “Le Daguerréotype,” the vous evoked by the narrator who climbs to the second floor of an immeuble (apartment building) to have his or her portrait taken is of ambiguous nationality, a fact evident when the narrator states at the beginning of this chapter, “Les Parisiens ne sont pas les seuls à se faire daguerréotyper: les étrangers qui sont venus visiter Paris ne veulent pas en partir sans avoir essayé de cette invention.”94 Here the vous may be a Frenchman from the country, a Parisian, or even a visitor from outside the Hexagon. In the chapter “Les Bains à Domicile” the vous begins as an impersonal pronoun but is soon referred to as “Madame,” changing gender from the previous vignette. The female vous returns in the episode “Le Vent” when the narrator calls out to women in danger of having their skirts blown by the wind.

Throughout the vignettes colloquialisms and cultural facts are explained to interlocutors, as if some will comprehend certain aspects of Parisian life and others will not. In fact the narrator calls out explicitly to readers of different classes. For example, in “Chantier de Bois à Brûler,” he declares, “Vous qui vous chauffez agréablement les pieds devant un bon feu . . . bon bourgeois, commis, hommes d’affairs, employés rentiers, vous tous qui sans avoir une assez grande fortune pour charger votre intendant ou vous domestiques des détails intérieurs de votre maison” and later, in “La Galette,” “Vous qui, pour vous enrichir, croyez qu’il est nécessaire d’aventurer de nombreux capitaux.”95 De Kock’s vous here thus seems to encompass all Parisian citizens and to invite each one to come to their own understanding of this nuanced city. The narrator addresses as wide an audience as possible and, by extension, makes the work as widely consumable as possible.

De Kock’s almost frantic, ever-shifting interlocutor—changing genders, professions, classes, and even nationalities—can be seen from a noncommercial standpoint when one considers the context of its eighteenth-century predecessor. As Priscilla Ferguson points out, Mercier’s text was radical for its democratic view of the majority of the city of Paris: “The consequent jumble of the text faithfully reproduces the disarray of the city. Both, in Mercier’s aggressively egalitarian view, repudiate the hierarchy and chronology that implicitly or explicitly order the conventional guidebook.”96 If Mercier’s guide is “radical” for reproducing the chaotic nature of the city with his short tableaux and for almost anticipating the Revolution with his writings on the poor Parisians as well as the rich, de Kock’s guide reflects a more complex politics of class, equality, and inclusion concurrently being played out in the Paris of his time. Such an overtly all-inclusive narrator might also be seen from a commercial perspective as a way of targeting as broad an audience as possible (within the limits of those who could pay to purchase the text either in the fifty-two weekly installments or as a bound edition). This is the same sort of marketing from within that we saw with the physiologies. Despite this similarity, in its form and content de Kock’s La Grande Ville is as emblematic of large-scale panoramic texts, whose hybridity stood in contrast with the more fixed physiologie.

Classifying Panoramic Literature

An examination of the Bibliographie de la France and other midcentury literary bibliographies shows that at the moment of their publication and shortly after, the “panoramic literary” texts betrayed a generic instability, suggesting that the contemporary literary field had difficulty classifying the phenomenon with the tools available to it. Beginning in 1811, the Bibliographie de la France was the official, national bibliography in which all legally registered works were listed as a matter of practice; they were indexed by title, author, and genre, and the titles of these generic categories varied occasionally.97 This literary database avant la lettre was administrative, but it was also, as its subtitle, Journal général de l’imprimerie, and its supplementary, Feuilleton, suggest, a professional tool for publishers. In addition to indexes of authors and titles, mid-nineteenth-century editions of the Bibliographie contained a section entitled “Table Systématique,” under which works were classified, first under a more general rubric (“Sciences et Arts,” “Théologie,” and “Histoire,” for example), and then under more specific subcategories (“Finances,” “Liturgie,” and “Histoire de France,” for example). Both the physiologies and their larger, more expensive counterparts were most often found indexed under the general rubric of “Belles Lettres,” a category that predictably contained subgenres like “Romans et Contes,” “Poétique et Poésie,” and “Théâtre.” Under the heading “Belles Lettres,” a vaguer category of “Philologie, Critique, Mélanges” existed for texts that could not easily be classified but still fell under the rubric of the literary. Between 1831 and 1848 the physiologies were one of the most prominently featured texts in the category of “Mélanges.” With a few exceptions physiologies ranging from the infamous 1832 Physiologie de la poire to the 1834 edition of Balzac’s Physiologie du mariage appeared in this “Mélanges” category, along with more than sixty of the physiologies published in 1841 and more than twenty published in 1842, at the height of their popularity.98 The physiologies thus were reliably read by the publishers of France’s official bibliography as belonging to no clear literary category, yet nonetheless as literary. Their uniform categorization as hybrid shows both an awareness of these texts as embodying a tension in the literary field on the part of the professionals who classified them (and, by extension, those who consulted this document in order to sell them) and, more generally, the instability of literary genres at this moment.

Lyon-Caen notes that the “Bibliographie de la France . . . range bien la littérature panoramique et les romans dans la section ‘Belles Lettres’ et les enquêtes sociales dans la rubrique ‘Economique politique’ de la section ‘Sciences et arts,’” in her contention that though the panoramic literature and the “enquêtes sociales” share common practices and “brouille[ent] les frontières de genres et registres,” these texts were seen as distinct at the time.99 Yet aside from the physiologies, the larger collections in the category “panoramic literature” were classified and reclassified, suggesting confusion about their genre. Though the Livre des cent-et-un was, like the physiologies, classified as “Philologie, Critique, Mélanges” from 1831 to 1833 and again in 1835, it was also catalogued as “Encyclopédie, Philosophie, Logique, Metaphysique, Morale” in 1834, a category that did not even fall under the overarching rubric of “Belles Lettres” but rather “Sciences et Arts.” Les Français peints par eux-mêmes was classified as “Encyclopédie, Philosophie, Logique, Metaphysique, Morale” in 1840 and 1842. While various 1833 and 1834 editions of nouveaux tableaux de Paris were also labeled under the “Encyclopédie” category, an 1835 nouveau tableau de Paris merited the label “Mélanges.” Curiously de Kock’s volume of La Grande Ville and the second volume, written in 1843 by Balzac, Dumas père, Soulié, and others, were placed in a third category: “Romans et contes.” Aside from the possibility that those in charge of categorizing these texts did not read them to determine their proper genres, one further simple explanation for this classification is that the contributors to the work were themselves well known for their novels and short stories and thereby classified accordingly. Nonetheless that a book documenting everyday life in Paris, in a decidedly non-fictional literary tradition, whose publisher openly stated in its prospectus that it was not a novel, should be officially categorized as “Romans et contes” raises significant questions about the way these texts were understood (even by those who produced them). These disparate categorizations indicate a distinction in most cases made by the publishers of the Bibliographie between the physiologie series and the larger collections of urban writings. Though not all of the literary guidebooks were classified under the same rubric, and at times (albeit infrequently) were labeled “Mélanges,” it is clear that they were not overwhelmingly read as generically identical to the physiologies.

These were France’s and the book industry’s “official” generic indexes of the panoramic texts, but other contemporaneous bibliographies and publications often replicated these categories when classifying the July Monarchy works. Mainstream publications such as the journal Revue Critique des Livres Nouveaux tended to place the physiologies they reviewed under a section entitled “Mélanges” in their table of contents. Works like the 1841 Physiologie de l’amour and Physiologie du parapluie (this second text written, anonymously, by “two coachmen”) were grouped under “Mélanges” in the table of contents. Their 1840 predecessors Physiologie du théâtre and Physiologie du chant were reviewed under the categories “Poésie, Art Dramatique” and “Arts Industriels, Beaux-Arts,” respectively. The Revue’s headings reproduce the Bibliographie de la France’s method of generally defining the physiologies as literary but occasionally categorizing them by the subjects they studied.

Over twenty years after the phenomenon of the physiologies and the tableaux had peaked, Pierre Larousse’s Grand Dictionnaire Universel du XIXe Siècle (published between the late 1860s and 1870s) also included a lengthy “Bibliographie générale” in its sixty-two-page entry on Paris (history, geography, culture, etc.) that replicates some of these generic categories and offers evidence of how this movement was viewed in the later half of the century. This particular bibliography, in which the author aims to detail “la série d’ouvrages de toutes sortes qui traitent de Paris à ses divers points de vue,” is split up into several categories, including “Descriptions topographiques, guides, plans, estampes,” “Moeurs et coutumes,” and “Romans.”100 We would expect to find the majority of the literary guidebooks listed under “Moeurs et coutumes,” defined by Larousse as “[où] l’on trouvera la liste de tous les ouvrages sérieux ou plaisants qui ont rapport à la physionomie de Paris et à la physiologie de ses habitants,” and this is indeed the case.101 Mercier’s Le Tableau de Paris and subsequent Nouveaux Tableaux de Paris (1833, 1855), de Kock’s La Grande Ville and Paris au Kaléidoscope, the multi-authored Le diable à Paris (1844–45), and other works are grouped under this category, as well as a small sampling of physiologies.102 Exceptionally Paris, ou le livre des cent-et-un is listed here under “Romans,” as de Kock’s literary guidebook was in the Bibliographie de la France. This work, whose publisher labeled it a “drame à cent actes divers” and “une encyclopédie des idées contemporaines . . . l’album d’une littérature ingénieuse et puissante,” and which was repeatedly categorized as “Mélanges” in the Bibliographie de la France, was situated, in other words, in a group with Hugo’s Les Misérables, Flaubert’s L’éducation sentimentale, Zola’s La Curée, and a number of Balzac’s urban novels.103 Like de Kock’s La Grande Ville, a book that also called attention to its nonnovel status but is nonetheless officially indexed as one in the Bibliographie, Janin’s “heterogeneric” work, to borrow Cohen’s phrase, was classified as a fiction (novels/short stories) by Larousse. These categorizations lead us to conclude that the hybrid form of the literary guidebooks transcended contemporary generic conventions, and in so doing fully embodied the moment of flux in literary history in which they were published.

In an attempt to establish a taxonomy of these panoramic works, themselves so focused on categorizing nineteenth-century culture, it has become clear that the nineteenth-century book industry resisted classifying these works in a uniform way, marking them as hybrid (“mélanges”), setting them apart from more clearly established categories, or inconstantly labeling them across generic categories (“sciences,” “belles lettres”) and subcategories (“tableau de moeurs,” “roman”).104 While the Bibliographie de la France is surely the most influential of these archives given its official status and great prominence in the nineteenth-century literary market, these other documents serve to stress the “authorized” bibliography’s fluctuating, varied classification of the literary guidebooks and its recurrent generic distinction between the physiologies and their larger counterparts. Pushed a step further, we might even posit that both the more fixed physiologies and the larger hybrid texts I have examined betray the instability of literary categories, the vagueness of all literary boundaries and genre even as they were being formed.

These panoramic works, which often incorporated references to commerciality and wide readerships into their form and content, explicitly staged the dynamism of the marketplace in which they were produced; not only their marketing but also their content served to promote the work. The publicity campaigns surrounding them developed as the phenomenon progressed, marking out clearly and in real time the new advances in the world of book advertising and the interconnected network of literature, advertising, and the press. Those authors linked to the phenomenon were often categorized as purely industrial writers, yet these texts also help to expose the blurring of boundaries between “high” and “low” authors. Balzac, as we will see, both contributed to and disparaged the trend of panoramic literature; de Kock—one of the major figures of this popular trend—more openly appropriated its typological tropes into his fictional works and, paradoxically, often received critical praise for just these passages. When reading the work of these two authors, and others, through the lens of this overtly commercial phenomenon, a more complex picture emerges of the hierarchies of the early to mid-nineteenth-century literary field.