Watching the advance of the Russian cavalry towards Kadikoi from his vantage point above the battlefield, Lord Raglan saw the Turks on Campbell’s flanks begin to waver. He therefore sent a message to Lord Lucan at the Cavalry Division’s new position under the Sapoune Ridge, urging him to give Campbell active support. Lucan in turn ordered Scarlett to take eight squadrons of the Heavy Brigade to Kadikoi. Unknown to either officer, Scarlett was about to fight his first-ever battle at the age of 55. In the process, he would cover himself and his brigade in glory.

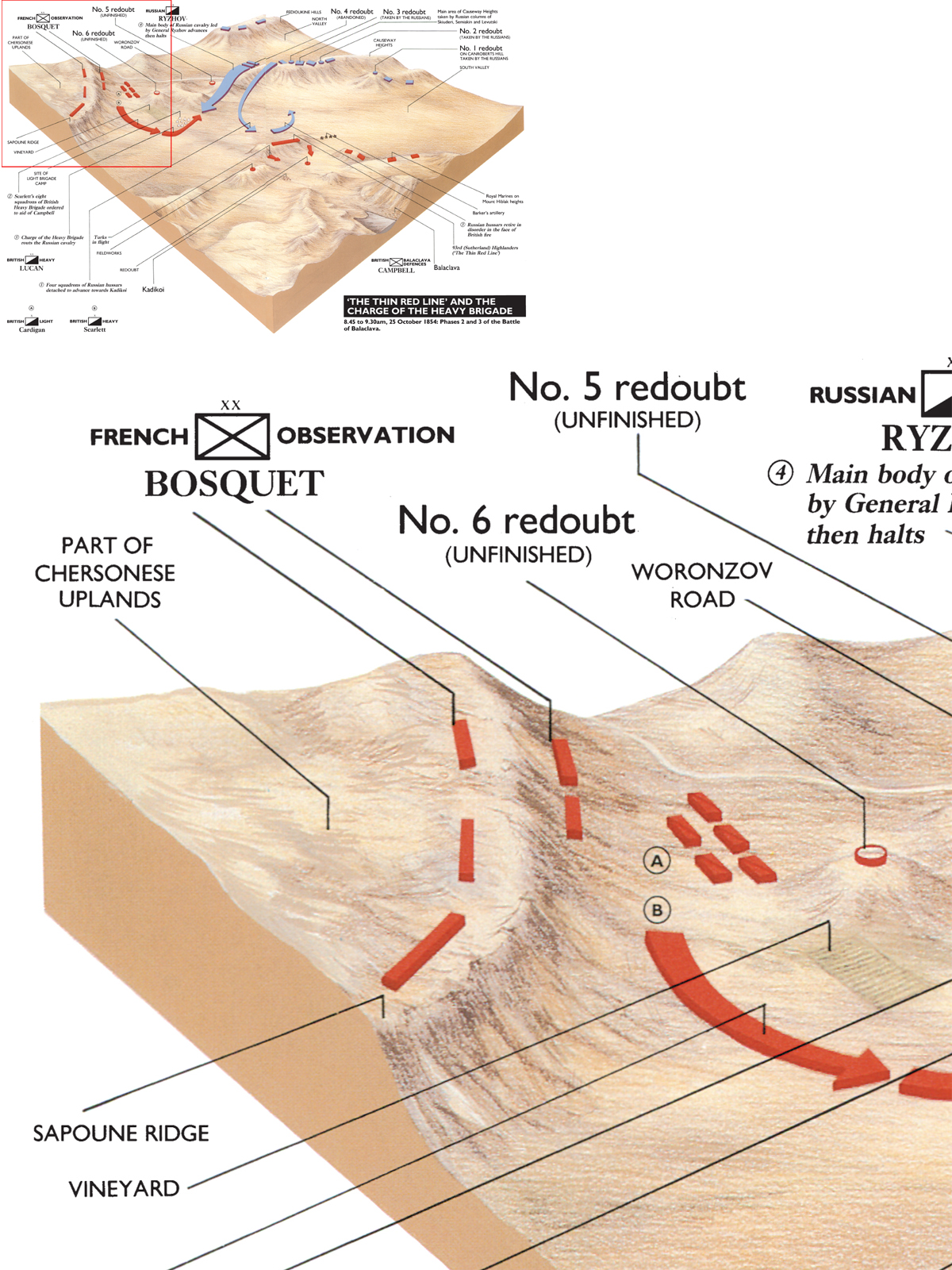

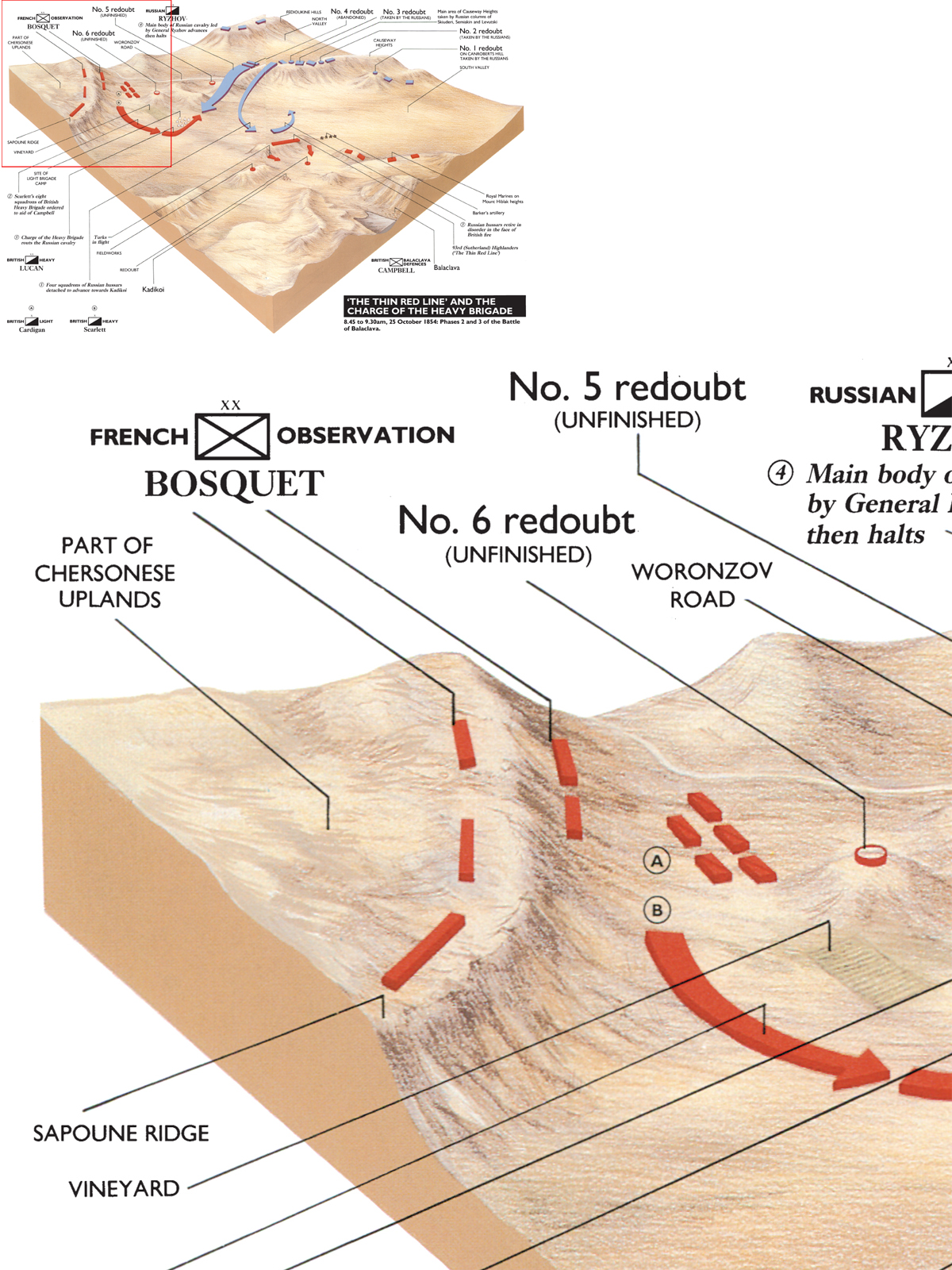

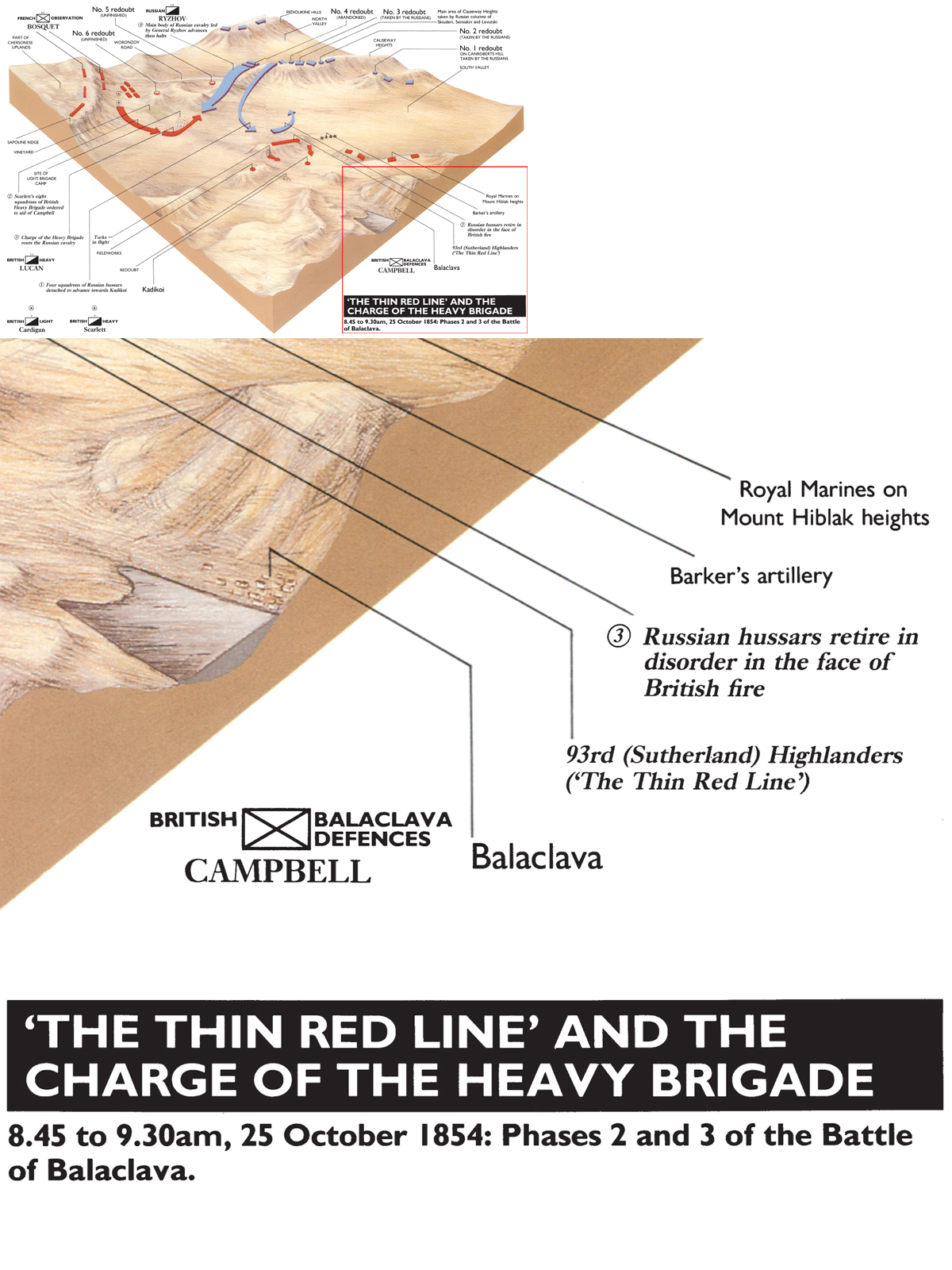

Still advancing westwards along the North Valley, after detaching the four hussar squadrons and Cossacks towards Kadikoi, Ryzhov came under fire from Allied batteries firing down on him from the Sapoune Ridge. However, just short of No. 5 redoubt, he wheeled his enormous body of cavalry left into South Valley aiming towards Kadikoi from due north. According to one Russian source ‘like Murat’ (Napoleon’s dashing cavalry leader), Ryzhov personally led the advance, not deigning even to draw his sword. Behind him the Ingermanland Regiment formed the first line in open order; in the second line rode the Kiev Regiment in column of attack. Cossacks covered the flanks. In reserve was another Cossack regiment, with the additional Composite Uhlan Regiment remaining under Liprandi’s direct control.

Trotting over the Causeway Heights, Ryzhov saw Scarlett moving across his front. Then the Heavy Brigade turned to meet him. When a little under 500 yards from his enemy, as he rode down the slope, Ryzhov became aware that the British were preparing to attack. Meanwhile, Liprandi, either sensing danger or, more likely, recognizing an opportunity to eliminate an inferior enemy force, ordered the reserve Cossacks into battle. Galloping hard and keeping up ‘their everlasting screaming’, they followed their own separate line of advance some 200 yards to the left of Ryzhov, where they would exert no real influence on the conflict. Already, British artillery in the Kadikoi area was finding its mark in the Russian ranks.

As it did so, Scarlett was deploying his small force to attack. Then, inexplicably, Ryzhov halted his main body, a mere 100 yards from the Heavy Brigade. Later he claimed that he had needed to reorganize his two hussar regiments side by side in the face of the extended line that Scarlett was forming. Perhaps so. However, he undoubtedly gave Scarlett the opportunity to charge a superior force while it remained stationary.

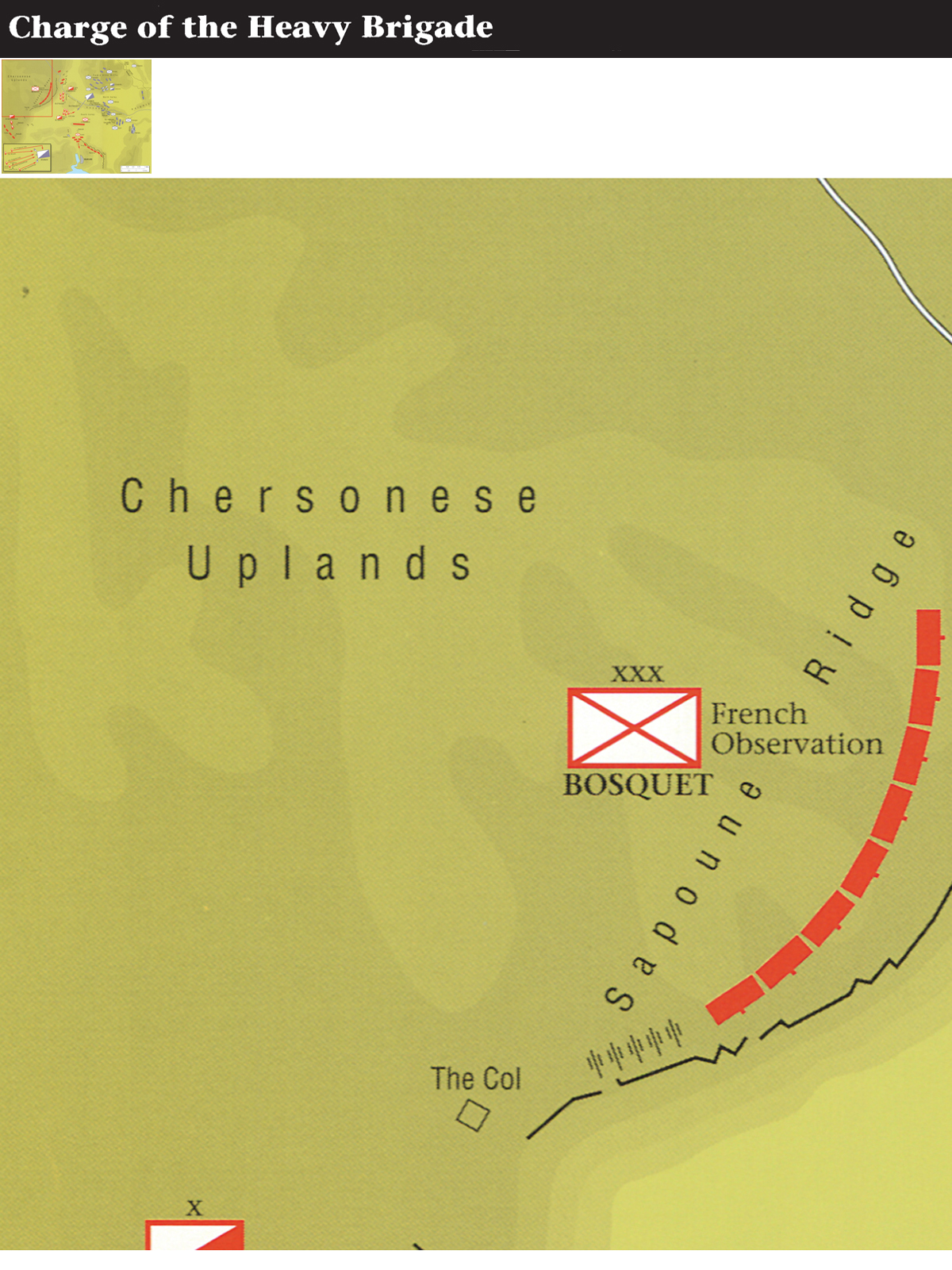

The Heavy Brigade commander had had difficult terrain to negotiate after leaving his position beneath the Sapoune Ridge to move eastwards. Apart from the broken nature of the lower slopes of the Causeway Heights over which the squadrons must move, there were two major obstacles. Just south of No. 6 redoubt lay an extensive, fenced vineyard (in some sources ‘plantation’) around which Scarlett must pass. This would clearly delay his advance. East of that area lay the Light Brigade camp, which had been abandoned in haste earlier in the morning. There, tents were still standing, while picket ropes and a few tethered sick animals remained. It was no place to fight a battle, let alone one where the cavalry had to pick its way uphill against larger numbers.

Scarlett had advanced with his squadrons in two columns parallel to the Causeway Heights and eighty yards away. On the right, furthest from the Causeway, one squadron of the Inniskilling Dragoons led, followed by both squadrons of the5th Dragoon Guards. The second Inniskilling squadron headed the left-hand column in front of the Scots Greys. The two squadrons of the 4th Dragoon Guards were further behind both columns. Scarlett and his ADC, Lieutenant Alexander Elliot, rode on the left of the left-hand column. They had been just skirting the Light Brigade camp when Elliot spotted the tips of lances above the Causeway Heights. According to some later reports, being short-sighted, Scarlett had thought these fuzzy shapes represented thistles, not enemy weapons; nevertheless, he soon recovered his poise. No lónger was he bent on reaching Kadikoi. A more potent danger had appeared on his flank.

Determined to attack the enemy, Scarlett ordered ‘left wheel into line!’ The left-hand column did, but as the Scots Greys were scarcely clear of the vineyard, Scarlett further ordered the squadrons to ‘take ground to the right’. This would certainly put them east of the vineyard but cause them to advance through the disorder of the partially-struck Light Brigade camp. Evidently Scarlett hoped that all six of his squadrons would attack by forming two extended lines, one behind the other. Warfare in its execution is seldom perfect. The right column had become divided on the march: the Inniskilling squadron in the van was well in advance of the 5th Dragoons on the right. So, when the order to wheel into line was given, the 5th Dragoons actually drew up slightly to the left rear of the Scots Greys. But the Inniskilling were far to the right in a very exposed position. The whole manoeuvre had been further complicated because the right-hand column had been marching by threes, the left-hand in open column. The actual charge would therefore take time to organize. And Scarlett would not be hurried. Perhaps this is what puzzled Ryzhov. As Raglan had earlier feared a ruse to allow a major attack out of Sevastopol, and the Russian hussars approaching Kadikoi suspected an ambush, Scarlett might be leading Ryzhov into a trap. Otherwise, why would he show so little alarm? Hence the bewildered Russians came to a halt. And Scarlett unhurriedly dressed his ranks.

Unknown to him, Raglan had alerted Lucan to the strength of the threat. As Scarlett’s officers were dressing their men with parade-ground precision, the 4th Dragoons were riding to help them. So, too, was the impatient Lucan. Galloping up as Scarlett wheeled his men into line for the second time, after moving to the right, he urged him to attack at once. With their backs to the enemy, however, officers calmly brought the squadrons into line. The first line had the two squadrons of Scots Greys on the left, the Inniskillings squadron on the right. The second line effectively had only the 5th Dragoons to the left rear of the Scots Greys: the other Inniskilling squadron remained too far to the right to support anybody. It was as the dressing was in progress that the Russian trumpets sounded and Ryzhov’s force came to a halt. Shortly afterwards, Russian horsemen were seen pushing out to the left and right fronts of the main body, giving the whole force something of a crab-like appearance, with claws ready to grasp an attacker.

Possibly aware of the danger to Scarlett if the enemy completed this movement before he charged, Lucan testily ordered the divisional trumpeter to sound the charge. In vain. If the squadrons heard him, they paid more attention to their own officers. Then at last the Heavy Brigade was ready. Scarlett with Elliot, his own trumpeter and orderly formed a tiny group ten yards in front of the first line. So eager were the Inniskillings in the first line to be away that Scarlett had to restrain them with his outstretched sword. They, fortunately, were well clear of the Light Brigade camp with an unrestricted view of the enemy and an unimpeded path in front. Not so the Scots Greys on their left. Finally, the front line did go forward; but Scarlett soon found himself leading just three squadrons against almost 2,000 enemy cavalry. ‘Scarlett’s 300’, as they were later called, followed the drill book. First came the order, ‘the line will advance at a walk’, then the trumpet successively sounded ‘trot’, ‘gallop’ and ‘charge’. Like Lucan, recognizing the absolute need to hit the enemy while he was still reforming and before he was himself attacked, Scarlett told his trumpeter to sound ‘charge’ almost as soon as the squadrons began to advance. But the Scots Greys, in particular, could not obey. The Light Brigade camp was proving a most difficult area to negotiate. Anxious not to dawdle, Scarlett half-turned in his saddle to urge the Scots Greys forward more quickly. They did pick up speed gradually, but when Scarlett and his small party drove into the Russian front, they were still fifty yards ahead of the nearest British horsemen.

To the spectators on the Sapoune Ridge, the scene was pure theatre. Elliot in his cocked hat rode beside Scarlett, who wore a blue frocked coat and burnished helmet rather than a general’s headdress. Slightly behind them rode a solitary trumpeter and Scarlett’s massive orderly Shegog. Together these four spurred ahead of the following squadrons. As the Scots Greys and Inniskillings sought to catch their brigade commander, he vanished into the enemy mass. He did so close to a Russian officer who, like him, had taken post in advance of his men. Elliot’s sword transfixed the Russian, but the impetus of the charge swung his body round as Elliot struggled to pull the sword out before being engulfed.

Brigadier-General The Honourable James Yorke Scarlett. Originally entering the Army in 1818, Scarlett had commanded the 5th Dragoon Guards (1840–54) without seeing active service. Appointed to command the Heavy Brigade with Lord Raglan’s Expeditionary Force, he distinguished himself at the Battle of Balaclava. Later in the campaign, he commanded the Cavalry Division and, after the war, became Adjutant-General at the Horse Guards. (Selby)

When the Scots Greys and Inniskillings bore down on the Russians, they met ragged, but effective, carbine fire. One of the first casualties was Lieutenant-Colonel Henry Griffith, commanding the Scots Greys, who was hit in the head. Major George Clarke, leading the right squadron of the Regiment, was luckier: he lost his bearskin, as his excited horse galloped forward, so he entered the Russian ranks bare-headed. The Inniskillings led by Lieutenant-Colonel Dalrymple White were the first to reach the Russians after Scarlett’s party, cheering madly as they did so. The Scots Greys, however, were not far behind, uttering a sort of fierce low moan.

Soon they were all fighting for their lives – 300 against 2,000. The Russians, mostly wearing heavy grey greatcoats and protective shakos, were so closely packed that the British found it difficult to wield their swords to effect. When they did so, the points rarely penetrated the thick Russian clothing. Only a few Russians were wearing a distinctive pale blue pelisse or hussar jacket. The British had red uniforms and helmets (with the exception of the Scots Greys, who wore bearskins). They did not wear shoulder scales, the restricting throat stocks or gauntlets. They were, therefore, in some respects more vulnerable than the light cavalry (hussars and lancers) who opposed them. The spectacle of small groups of red coats or desperate, isolated individuals hacking their way through the grey mass below them was both awesome and inspiring to the watchers high above the field. There, 1½ miles away on the Sapoune Ridge, the roars of men, neighs of horses and clash of steel on steel drifted on the breeze adding to the atmosphere of battle. But these indistinct noises could not convey the terror, bravery and sheer exhaustion being experienced amid that heaving throng.

Colonel William Ferguson Beatson. An experienced officer with irregular cavalry, Beatson had served with distinction under Sir George de Lacy Evans (commander of the 2nd Division in the Crimea) in Spain during the Carlist Wars and also with the Nizam of Hyderabad in India. The British government had hoped that he would organize Turkish irregular cavalry in support of the British troops with Lord Raglan. When this plan failed to materialize, General Scarlett used Beatson as an additional ADC. He was therefore influential in training the Heavy Brigade, but did not charge with it on 25 October 1854. He watched the Battle of Balaclava from the Sapoune Ridge. (David Paul)

Jabbing, slicing and cleaving his way forward, Scarlett sustained blows to the head that severely dented his helmet without scratching him, and elsewhere he suffered five wounds to his body. Here was a commander who led by example. His ADC (Elliot) was more seriously injured. At one point surrounded with little hope of survival, he was saved by his maddened charger’s lashing hooves. In all, Elliot sustained fourteen sabre cuts, one of which slashed his face extensively so that several stitches had later to be inserted. Another blow split his cocked hat and yet another temporarily knocked him out. He stayed in the saddle, however, and lived. The bare-headed Clarke predictably received a deep cut in his skull. Fortunately, it was at the rear, and the blood flowed freely down his neck unknown to him in the heat of conflict as he fought his way forward. Dalrymple White found himself fighting alone, suffered a blow which split his helmet in two and similarly was unaware of what had happened.

Some of the 300 actually emerged, having blasted their way right through the Russians, to face Cossack reserves drawn up behind the main body. As they did so the claws thrust out in front of the enemy force began to close behind them. A Light Brigade officer looking on gasped: ‘They are surrounded, and must be annihilated. One can hardly breathe!’ The truth was that, in that dreadful mêlée, this actually did apply to many a struggling man. Help seemed so far away. Realizing that unless his men rallied they were doomed, the adjutant of the Scots Greys bellowed above the din: ‘Rally the Greys . . . Rally the Greys!’ Bravely he backed down the hill, ordering his men to face him and reform – an incredible demand. Yet, still in that milling throng, many did manage to close on one another and the squadrons did achieve some sort of order. Without that, a lot more must have perished.

Officer, 4th (Royal Irish) Dragoon Guards. Riding east of the prominent vineyard in the South Valley and led by Lieutenant-Colonel Edward Hodge, the 4th Dragoons drove through the main body of Russian cavalry from left to right as it halted on the southern slopes of the Causeway Heights to receive the charge of the Heavy Brigade.

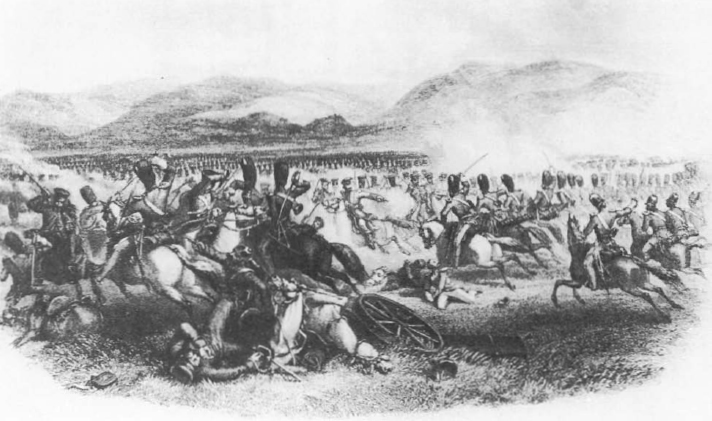

Charge of the Heavy Brigade. In the foreground is the imperfectly struck Light Brigade camp, through which some of the squadrons had to pick their way. This inaccurate reconstruction of events shows the first line of Inniskillings and Scots Greys (nearer), with the 5th Dragoons in close support. The second Inniskilling squadron is shown in the distance simultaneously asaulting the enemy left, while the 4th Dragoons appear just to the right of the scene. The 93rd on its knoll is shown in the middle distance, Kadikoi on the right and Balaclava in the background. The artist also depicts local Tartars plundering the Light Brigade camp during the attack. (Sandhurst)

In the meantime, the other three squadrons near to Scarlett as he closed on Kadikoi had attacked after the first line. The 5th Dragoons, who formed up in extended line slightly to the left rear of the Scots Greys, were seriously hampered by the Light Brigade camp, and some riders were unseated as their horses stumbled over picket ropes. Clearing these obstructions the two squadrons hit the forward part of the Russian right wing as the ‘claw’ wheeled and many of the troopers had their backs to the British dragoons. Subjected to some carbine fire, nevertheless the 5th Dragoons struck the enemy just as the Scots Greys were being forced back in the centre. Their arrival was therefore most opportune. Away to the right, in its detached position, the other Inniskilling squadron attacked the Russian left. Because of its relatively-advanced situation on the march to Kadikoi, under Major Charles Shute this squadron approached the enemy from an oblique angle. With no impediments in their path, the cavalrymen quickly picked up speed, and their advance was helped by thick herbage underfoot, which effectively muffled the hooves. Incredibly, like the 5th Dragoons on the far left of the attack, Shute’s force struck the Russian left wing (‘claw’ extension) as it was turning inwards. Driving rapidly into the mass, the dragoons seemed to carry the Russians back uphill with them. The unexpected nature and fury of their assault had caught the enemy completely by surprise. One Inniskilling officer carried a dead Russian across his saddle into the close-packed ranks, unable to throw the corpse off for lack of room.

Arriving in the area of the vineyard shortly after the first six squadrons, the 4th Dragoons had seen Scarlett’s 300 quickly and alarmingly vanish into the massed grey files. Skirting the eastern fence of the vineyard and picking their way through the western part of the Light Brigade camp, the two squadrons under Lieutenant-Colonel Edward Hodge advanced parallel to Scarlett’s line of attack to the west of the Russians, before turning almost at right-angles to charge the enemy right flank. Hacking their way forward, they drove straight through to come out on the enemy’s eastern (left) flank. Hodge emerged about the same time as, and close to, Scatlett, who had fought in a half circle to his right and also emerged half way along the enemy left flank.

The two squadrons of The Royals that had been left behind with the Light Brigade followed their commanding officer (Lieutenant-Colonel John Yorke), who acted on his own initiative without receiving orders. Advancing in the wake of the rest of the Heavy Brigade, The Royals had passed the vineyard just as the Scots Greys appeared to be in dire trouble prior to their adjutant’s command to rally and as the 4th Dragoons were preparing to launch their flank attack. A voice called: ‘By God, the Greys are cut off! Gallop! Gallop!’ The Royals cheered and surged forward quickly, with the result that they did not put in a coordinated attack on the enemy right. But their appearance served further to confuse the Russians, who were now being attacked from a fourth direction. The Royals only exchanged ‘a few sabre-cuts’ with the enemy, incurring minor casualties, before Yorke recalled them to reform. Prior to that order, however, Troop Sergeant Norris had suffered a bizarre experience. Delayed by clutter in the Light Brigade camp, he had galloped hard to catch the others, but was cornered by four Russians. Reacting vigorously, he killed one and drove off the other three.

Another portrayal of Brigadier-General Scarlett’s charge, showing the Scots Greys (in bearskins), with The Royals too close behind them. Note the Russian officer in the centre discharging his pistol, but the men behind him still with their swords at the slope. (Sandhurst)

This contemporary print attempts to convey more of the confusion, death and smoke on the battlefield. (David Paul)

As Scarlett and Hodge came out of the enemy left, the Russians were beginning to break. Afraid that his men would pursue them too far and be exposed to decimating artillery fire or counter-attack, Hodge ordered the nearest trumpeter to sound the rally. It was only just in time. The Dragoons had already come under fire from batteries across the North Valley on the Fedioukine Hills. As the enemy broke, Barker’s battery near Kadikoi, Maude’s battery with the Light Brigade and three Turkish guns in a defence-work close to the Col of Balaclava opened fire on them. In desperation, Liprandi sent forward his reserve lancers from the Composite Uhlan Regiment. When case-shot began to hit them, he reversed the order. It was all over. Russian sources later admitted to being ‘crushed’.

The whole action from the time that Scarlett started his charge to the enemy retreat took a mere eight minutes. It cost the Heavy Brigade 78 casualties; the Russians suffered 270, including Major-General Khaletski wounded. The threat to Kadikoi had again been stemmed. The inner defences of Balaclava remained intact.

A watching French general declared: ‘The victory of the Heavy Brigade was the most glorious thing I ever saw.’ Edward Hamley similarly observed: ‘All those, who had the good fortune to look down from the Heights on this brilliant spectacle, had a vivid recollection of it.’ Away to the east, the cheers of the 93rd carried on the wind, and Campbell rode up to offer his personal congratulations. Doffing his hat, he cried: ‘Greys! Gallant Greys! I am sixty-one years old, and if I were young again I should be proud to be in your ranks.’ To Scarlett, Raglan sent a short, but heartfelt, message: ‘Well done!’

Well done, indeed. But what of the Light Brigade, whose 700 men had watched the engagement idly from afar? A flank attack by them might well have cleared the enemy cavalry right off the battlefield and back across the Tchernaya. Unknown to them at the time, it would also have prevented the military holocaust that lay in store for them.

500 yards to the west, the Light Brigade was drawn up in two lines, to one embittered cavalryman as ‘spectators’. Cardigan, despite pleas from his officers, would not move. Yet, according to many, he rode restlessly up and down the line muttering: ‘Damn those Heavies, they have the laugh of us this day.’ Vicomte de Noe, an experienced French observer, believed that the retreating Russians could have been ‘annihilated’ if Cardigan had charged their flank. ‘This was the occasion’, he concluded, when ‘there should have been exercised the initiative of the cavalry general.’ Cardigan blamed his inactivity upon his hated brother-in-law. He later explained: ‘I had been ordered into position by the Earl of Lucan, my superior officer, with orders on no account to leave it, and to defend it against any attack of Russians.’ He added laconically: ‘They did not, however, approach the position.’ In his mind, therefore, his lack of action was both logical and excusable. His orders had not permitted him any latitude. As de Noe added, ‘Later in the day it was made apparent that bravery is no sufficient substitute for initiative.’

Cardigan’s shortcomings, which could have turned a local victory into a decisive rout, should not obscure the magnitude of Scarlett’s achievement. The third phase of the Battle of Balaclava, like the second, had gone in favour of the British. It was still only 9.30, and the spectacular, bloody and unnecessary slaughter of the fourth phase was yet to come.

Trooper, 11th (Prince Albert’s Own) Hussars. Led by Lieutenant-Colonel John Douglas, the 11th Hussars formed the second line during the Charge of the Light Brigade. For twelve years (1836–47), Lord Cardigan had commanded the regiment.