There was no snow on the ground. The breeze was warm, not cold, and the hillside was bright green, not barren or snow covered. But it was Christmas in July in Bowling Green, Ohio, on July 26, 1948.

At least as far as Paul Brown was concerned. The gifts weren’t under a tree, and they hadn’t been delivered by a jolly fat man with a white beard wearing a red suit. They had come from all parts of the country by more conventional conveyances than a sleigh pulled by eight flying reindeer. They’d call the dormitories of Bowling Green State University their home for the rest of the summer. The lucky ones, 35 in all, would make the short trip east to Cleveland in late August.

“This is Christmas all over again for me,” enthused Brown. “That’s because I see so many of these new players at really close range for the first time. The situation is full of surprises. They look different here than when we saw them with another team in our league or in the uniform of a college team. I always look forward to the first day in camp. It is one of the most interesting of the season.”1

Brown was like a kid who’d gotten an erector set for the holiday. But the pieces he’d be playing with weren’t made of metal, and he wouldn’t be building a skyscraper or an office building. He’d spend the next six weeks constructing a football team. One that he hoped would successfully defend its status as champions of the All-America Football Conference.

One of the players Brown got his first look at up close was tackle Forrest (Chubby) Grigg, who’d been obtained in an off-season trade with the Chicago Rockets. Grigg had come by his nickname honestly, and Brown wanted him to shed some of his excess weight before he reported to training camp. As an added inducement (avoiding Brown’s wrath was generally more than sufficient inducement for most players), Brown promised Grigg a bonus of $500 if he weighed in at less than 280 pounds. When the big moment arrived, Grigg stepped on the scale, and it registered an even 250 pounds. No one, not even Grigg, believed that figure. A second attempt again revealed a weight of 250 pounds. A quick investigation showed the scale’s spring to have broken. Another scale was procured, and Grigg stepped aboard. The needle made its way to 272½ pounds, and stopped there. All were satisfied with the scale’s accuracy. Grigg had slimmed down as ordered, and Brown anted up. It turned out to be money well spent.

Brown had introduced the classroom to professional football, and the first day of practice was spent inside one. Brown presented to the players the results of a study conducted by his coaching staff of every play the team ran during the 1947 championship season. “This is really enlightening,”2 Brown told his charges. The study showed the Browns ran the ball 60 percent of the time and threw it 40 percent of the time. The average gain per rushing play had been an outstanding 5.2 yards. The average gain per pass play had been an equally outstanding 8.1 yards. Brown then distributed the team’s 1948 playbook. The players were expected to be well on their way to having it memorized by the next day, when they took the field for the first time.

A team with a 12–1–1 record (13–1–1 including the championship game) doesn’t have many weaknesses, but Brown was concerned about the depth of his offensive backfield. A pair of lengthy practices on July 28 gave him reason to believe that wouldn’t be a problem in 1948. Twenty players were competing for jobs in the backfield, including Bill (Dub) Jones, a halfback acquired from the Brooklyn Dodgers during the off-season in exchange for the draft rights to quarterback Bob Chappuis from the University of Michigan. Jones had gained 136 yards rushing for the Dodgers in 1947, but Harold Sauerbrei, who covered the Browns for the Cleveland Plain Dealer, expressed the opinion that Jones would have trouble making the final roster against competition from Bob Brugge, Dean Sensabaugher, Tommy James, Ara Parseghian, and local products Warren Lahr (from Cleveland’s Western Reserve University), Vince Marotta (from Mount Union) and Charley Heck (from Ohio Wesleyan). Jones stuck and became one of the Browns’ primary offensive weapons, both as a running back and receiver.

“We’re definitely going to be better in the backfield,” said Brown. “Not only at the halfbacks, but at the other two jobs as well.”3 Two of Brown’s assistants weren’t as sanguine after the first outdoor practice. Offensive line coach Bill Edwards was concerned that his tackles were carrying too much weight. Defensive line coach Dick Gallagher was searching for another quality end. There would be plenty of time in Bowling Green to address both issues.

The Browns announced on August 2 that tickets for all home games in spacious Municipal Stadium would go on sale immediately at Richman Brothers clothiers at 736 Euclid Avenue, and Burrows books and office supplies at 419 Euclid Avenue. Ticket prices weren’t mentioned.

It turned out the veteran Dub Jones didn’t have much to fear from Marotta and Heck in the battle for a job in the Browns’ crowded offensive backfield. Both were released before the team’s August 3 scrimmage, as was rookie quarterback Stan Magdziak from William and Mary College. Magdziak had no chance to unseat Graham, and his chance to stick as a substitute was ruined by the recurrence of a nagging hip injury early in camp. The Browns also cut center Gus Langley of Louisiana College to trim their roster to 43 players. That number would vary from practice to practice as players were released or traded away, and imported from other camps through trades or waiver acquisitions. Brown was constantly searching for diamonds in the rough overlooked by less savvy coaches, or players he thought might flourish in Cleveland’s system, or when surrounded by more talented teammates.

With one week of practices behind them, and an intra-squad scrimmage awaiting, linebacker Lou Saban, in his third season with the Browns, offered his impressions of what he’d seen after seven days in Bowling Green. “I’m not predicting a third straight title for us, understand,” Saban said. “But from what I’ve seen so far, we’re going to be plenty tough. The veterans are hustling, which is a good sign. They realize we’re in for a rough schedule, starting with the Los Angeles Dons, who have the best two-year record against us. Nobody is loafing, or giving any other indication that we can coast, simply because we won the title two years in a row. The new players have caught the spirit of the thing and are keeping right up with us. Those new halfbacks, especially, look very good. They’re solid, and they’re fast. That’s the position where we needed help the most, and it looks as if we’ll get it.”

Knowing his coach liked his players lean, Saban said he was keeping his weight down by doing without sugar in his coffee. “I’ve got to set a good example.”4

Brown held his first scrimmage on August 3. He went easy on his star quarterback, Otto Graham, as all the defensive players Graham faced were rookies. Sauerbrei described it as a typical first scrimmage with some good plays, some bad plays, and plenty of early training camp mistakes. Dub Jones caught his coach’s eye by scampering 62 yards, the longest run of the day, setting up a seven-yard touchdown burst by Marion Motley. A 27-yard pass from Graham to Bill Boedeker put the offense in position to score on an eight-yard run by Tom Colella. Colella was also busy on the third possession, gaining 34 yards on just two carries. Ollie Cline, a rookie from Ohio State (Brown liked Ohio State players) ran 31 yards to put the ball inside the 10-yard line, and Brugge ran it in from the seven for the touchdown. Graham worked with three sets of halfbacks and three sets of fullbacks. Brown held the scrimmage earlier than he would have preferred because he wanted to get a look at three players, Cline being one of them, who’d be leaving camp to join the college all-stars to prepare for their game against the NFL champion Chicago Cardinals.

Brown kept passing too a minimum since Graham had a sore arm from too much throwing too early in camp, and his back-up, Cliff Lewis, hurt his leg in a drill just before the scrimmage began. Brown termed the scrimmage “ragged” but said he saw enough to learn a few things about the rookies who had survived the first cut.

On the downside, rookie center Paul Goll of Western Reserve University had to leave the scrimmage with a cut on his left leg that required eight stitches to close. Goll had little chance of making the team to begin with, and the time he missed due to the injury was too much for him to overcome. He wouldn’t play professional football.

Alex Agase from the University of Illinois was among the scrimmage’s more impressive performers. Agase had come to the Browns from the Rockets in the same transaction that brought Grigg to Cleveland. On offense, Agase played guard and executed two blocks that resulted in big rushing gains. He credited the coaching he’d received in his first week in camp. “In all my football playing, they always diagrammed the play and pointed out the man you were supposed to block,” said Agase. “Here, they tell you whom to take and how to do the job. Without the coaching I have received here in the last week, I never would have made the blocks against those ends.”5 Agase’s main contribution to the Browns would be on defense, and his play at linebacker impressed his coach.

“He’s alert, he does things instinctively, and he’s tough,” said Brown of Agase. “He’s going to be very helpful on pass defense.”6 And Brown was concerned with defending the pass, although most teams preferred to move the ball on the ground. Brown has long been credited, and deservedly so, with inventing the modern passing game. But, as one who knew how to throw the ball effectively (Brown played quarterback at Massillon High School and Miami University of Ohio), he also knew how to stop others from throwing effectively. Brown’s teams were always tough to throw against.

One player who didn’t contribute much in the scrimmage was Warren Lahr. That was because, with the release of Magdziak, the Browns were in need of a quarterback to spell Graham and Lewis, whose primary position was defensive halfback. Lahr had been a quarterback at Western Reserve University, right in the Browns’ back yard, and after watching him throw the ball in early practices, Brown decided to shift him from halfback to quarterback.

“People have been asking what we would do if anything ever happened to Otto Graham,” said Brown. “Well, he’s our answer. That kid’s going to be a great quarterback.”7

Lahr was nervous about changing positions. “I’m as jittery as the time my sisters got me to go out for the high school football team,” he admitted. Lahr weighed just 130 pounds as a teenager, and his mother wouldn’t sign the parental permission slip allowing him to play for Pennsylvania’s West Wyoming high school. His two older sisters (Lahr had seven siblings) said they’d take responsibility and signed the document, and he played well enough in high school and college to earn a shot with the defending AAFC champions.

“I’m not too worried about the passing,” said Lahr of the learning curve he’d have to master to become a professional quarterback. “But I have a lot to learn about feinting and footwork, and I have to become familiar with the various speeds, habits and styles of our backs and ends. You have to know how much ‘lead’ to give a receiver, and you have to know when to hand the ball to the different ball carriers. But if I don’t learn all those things, it’ll be my own fault. Blanton Collier and Graham and Cliff Lewis have been spending a lot of time coaching me. Otto and Cliff have been wonderful about helping me correct my mistakes.”8

Brown wasn’t wrong very often when evaluating players, but he missed the boat on Lahr. His future was in the defensive backfield. Lahr would make a career out of defending passes rather than throwing them from 1949 to 1959, after missing the entire 1948 season with an injury. He intercepted 44 passes for the Browns, returning five of them for touchdowns. The player Brown thought was going to be a great quarterback threw one pass in his NFL career, in 1954. It was picked off.

It was said that Brown liked his players “lean and mean.” Players who feared the very thought of being cut from the team and played as hard and as well as they possibly could in order to prevent that from happening. Players like defensive end George Young, who could be heard muttering to himself as he walked to and from the practice field, “I’ve got to make this team. I’ve got to, or it’s back to Frosty Fort for me, and who knows what.” Young knew that whatever awaited him in Frosty Fort, his hometown near Wilkes-Barre in Pennsylvania’s Wyoming Valley, wasn’t nearly as appealing as playing football in Cleveland. Young’s mother died when he was 10 years old, and his memories of home weren’t pleasant.

“After our mother died, my sister and I usually opened a can of beans or soup for our evening meal,”9 Young recalled during training camp. Despite such a meager diet, he grew big enough to play football and was part of Brown’s 1944 Great Lakes Naval Training Station team. He transferred to Shoemaker, California, in 1945 and played for the Fleet City Bluejackets, the national service champions.

Young could, and would, play with pain. He sprained his ankle on the first day of training camp in 1947 and struggled to make the team. Brown chose to keep Young and cut Bill Huber, who had a chronic foot injury. In spite of the pain, Young graded out, in Brown’s intricate system for assessing player performance, as the Browns’ second most effective defensive player for the season. Coach Blanton Collier gave Young a grade of 3.40 on a scale of 4. Only “Jumbo” John Yonakor achieved a higher score (and barely, at 3.41).

Young played in 1948 with a nine-and-a-half-inch calcium deposit on his right thigh. The doctors who’d recommended surgery (and who said they’d never seen such a large deposit) told Young he’d lose half of his mobility if he had the deposit surgically removed. Afraid of sacrificing his football career, and returning to Frosty Fort and an uncertain future, he refused to go under the knife. The deposit stopped growing and didn’t bother Young when he played.

Young got Brown’s attention during the scrimmage when he tackled rookie halfback Ara Parseghian for a 10-yard loss. Young was on Parseghian so quickly after he took the handoff from Graham that Brown was sure he’d heard Graham’s play call in the huddle. Young denied it. “I didn’t hear the signal, but I knew where [the play] was going,” Young said. “Ara pointed when he came out of the huddle.”10

Fear was a potent weapon in Brown’s coaching arsenal. That was why he liked players like George Young. Players who were talented, smart, and deathly afraid of losing their jobs.

Guard Dick Mazuca from Canisius College lost his job with the Browns on August 4. That reduced the roster to 41.

Brown’s high school coach at Massillon, Dave Stewart, visited Bowling Green during the first week of August. He shared some reminiscences of Brown’s playing days at the school where he later established his reputation as a coach. “I don’t think he weighed as much as 100 pounds,” Stewart told Herman Goldstein, the football writer for the Cleveland News. “I told him he was too small.”11 Brown refused to take “No” for an answer, and Stewart fondly recalled Brown’s first play for the Tigers. The recollection doubtless didn’t surprise any of Goldstein’s readers. Brown saw his first game action when Stewart sent him in with Massillon in possession of the ball on its opponent’s seven-yard line. Brown had instructions to throw, and he completed a pass to a player named King for a touchdown. It was a portent of things to come for Brown as both a player and a coach.

“In his last year, I did no substituting at all,” Stewart confessed to Goldstein. “Paul ran the team on the field, made the changes he wanted. Thinking back about the kid who wanted to go to camp that first year, it seems like Paul was destined for football.”12

Stewart gave an example of why he allowed a teenager to serve as coach on the field. Stewart noted that in his five years as head coach, Massillon defeated its arch-rival, Canton McKinley, four times. He explained what happened the only time the Bulldogs topped the Tigers. Late in the game on a rainy night, Massillon held a 3–0 lead and faced a fourth down in the shadow of its goal line. Brown wanted to take an intentional safety, which would have cut the Tigers’ lead to 3–2, but would give them the opportunity to free kick to McKinley from the 20-yard line. Brown didn’t want the punter, Paulie Smith, to have to kick from inside his own end zone and risk a block that could be recovered by McKinley for a touchdown. Brown’s teammates protested, saying they didn’t want to intentionally give up the shutout they’d worked so hard for. Brown changed his mind, and Smith’s punt traveled only 28 yards. McKinley took advantage of the short field to drive for the winning score in the game’s closing seconds. The outcome still rankled Stewart and Brown many years later. Such was the nature of the Massillon-McKinley rivalry.

The team held its annual training camp family picnic on Sunday, August 8. In the words of Bob Yonkers, the football writer for Cleveland’s afternoon newspaper, the Press, it was the only day of the Browns’ six-week stay in Bowling Green that could have been considered a “picnic,” although Brown wasn’t known for long and grueling practices. He rarely worked his team more than an hour and a half, and the practices were scripted down to the minute. He also didn’t believe in his players beating on each other in practice any more than was necessary. He preferred to have his players as fresh as possible, and ready to take out their aggression on that week’s opponent.

While the Browns were preparing to defend their AAFC championship, back in Cleveland, the Indians were trying to win a championship of their own. The hottest American League pennant race in 28 years was in full swing in early August. The Indians were in the thick of a four-team race with the New York Yankees, Boston Red Sox and upstart Philadelphia Athletics. That had the potential of creating a problem for the Browns. If the Indians were to win the pennant, the fifth game of the World Series would be played in the American League winner’s home stadium on Sunday, October 10. The Browns were scheduled to host the Brooklyn Dodgers the same afternoon. The World Series game would take precedence (if for no other reason than the Indians were Municipal Stadium’s primary tenant and had dibs on playing dates) and the Browns announced they’d play the Dodgers on Tuesday, October 12. That plan didn’t last long.

The Indians, meanwhile, were worried about the damage the Browns would do to the Municipal Stadium playing field, particularly the infield, when they played at home on September 3 and September 26. Chief groundskeeper Harold Bossard wasn’t concerned. Even if the Browns played in the rain, Bossard said the football games wouldn’t do significant damage to the field. “If it doesn’t rain, it would be just a matter of replacing the divots,”13 said Bossard, whose family kept Municipal Stadium’s playing surface in immaculate condition through the 1960s.

The words “revolutionized” and “Paul Brown” will be paired often in this narrative. One of the areas Brown concentrated heavily on that most coaches had glossed over was the kicking game, both as an offensive and defensive weapon. The Browns had punted 52 times in 1947, and not one of Horace Gillom’s boots had been blocked. Gillom, another Ohio Stater (and Massillon alum) recruited by Brown, had averaged 44.6 yards per punt, and Brown was looking to improve on that in 1948. Brown dedicated the team’s entire practice session on August 11 to punt protection and coverage. Brown knew it could make the difference between winning and losing a game someday.

“We have a certain way of setting this up,” Brown explained. “Punting and place-kicking are a couple of pretty important phases of our football, and we want to devote a lot of time to them. We’re pretty proud of that record of no blocked punts and want to add to it.”14 After a morning classroom session, the players practiced in the rain in the afternoon. There was no indoor facility available for rainy days, and besides, the players needed to get accustomed to playing in wet conditions. Football games weren’t postponed due to soggy weather.

In addition to hosting the Browns, Bowling Green would host 21 AAFC game officials the weekend of August 13–15. They’d attend a conference at which “all phases of their jobs will be discussed.”15

Each summer, an intra-squad game pitted the Browns’ veterans against their rookies and substitutes. It would allow fringe players such as tackle Art Christ of Springfield College, end Tod Saylor of Lafayette College, and tackle Ben Pucci, obtained from the Chicago Rockets, to show their stuff. The rookies would be without tackle John Prchlik and halfback Ollie Cline, who were with the College All-Stars preparing for their game against the NFL champion Chicago Cardinals. An appearance by the “famous musical majorettes,” a creation of Browns owner Mickey McBride who entertained at halftime of the team’s home games, would add spice to the festivities at Bowling Green high school. The majorettes needed practice, too.

A curious crowd of 2,000 attended the Browns (veterans) versus Whites intra-squad game on August 14. Though not a great deal more than a glorified scrimmage, it was four quarters long and approximated game conditions as nearly as possible. It was, however, informal to the point that Otto Graham, although one of the Browns, played quarterback for the Whites, too, in order to get some extra work. The Browns took the opening kick-off and Graham easily drove them 75 yards for a score. Motley ripped off a 17-yard run and Graham completed four passes. A six-yard toss to Bob Cowan gave the Browns a 7–0 lead. With the score 14–0, Brown put Graham in charge of the Whites’ offense (turning the Browns’ offense over to Cliff Lewis), and Graham took them 63 yards to the Browns’ five-yard line. A pair of touchdown passes were negated by penalties, and the Whites didn’t score. Graham then retreated to the bench for the rest of the afternoon, and the 14–0 score stood.

Sauerbrei singled out defensive lineman Bill Willis, linebacker Agase, punter (and occasional offensive end and defensive lineman) Gillom and offensive end (wide receiver using today’s terminology) Roy Kurrasch as the scrimmage’s outstanding performers. Kurrasch was also hoping to win a roster spot as a back-up defensive end in an era when many players saw action on both sides of the line of scrimmage. Sauerbrei had special praise for Ed Sustersic, a product of nearby Findlay College, who was trying to earn the Browns’ “third back-up fullback” job. According to Sauerbrei, Sustersic excelled on both sides of the ball, and it was obvious the writer was cheering for the hometown boy. Sustersic was a graduate of Cleveland’s John Marshall high school. His chance to earn a roster spot in 1948 ended when he broke his arm during the Browns versus Whites scrimmage. He’d make the team in 1949 and gain 114 yards rushing, scoring one touchdown. It was Sustersic’s only season of professional football.

Far more important than which players impressed Sauerbrei (or Yonkers or Goldstein), was which players impressed Brown. The coach praised the defensive performances of Ara Parseghian and Tommy James. Lahr quarterbacked the rookies and, though he failed to produce any points, flashed his versatility by running for 35 yards on the (numerous) occasions that he couldn’t locate an open receiver. He didn’t get a lot of help from his offensive line, as Brown noted during film study of the game. On one play, Willis drove center Frank (Gunner) Gatski and Lahr to the turf. Brown put the projector in reverse and ran the play again for Gatski’s benefit.

“What in the world happened there, Frank?” Brown demanded to know. “You were taken apart. You were supposed to block that man. You didn’t give Lahr any protection at all.”16

Gatski, while careful not to challenge Brown, mounted a defense. “Show that play again, Paul,” he asked. Brown preferred that his players address him by his first name, rather than as “coach” or “Mr. Brown.” Gatski continued, “Watch Bill Willis. You’ll see what happened to me. Bill hit me before I even completed the [snap] to Warren.”17 Willis had penetrated the Whites’ backfield without being offside and sacked both the center and the quarterback! Often, the toughest opponents the Browns’ players would face were their own teammates in practice. Gatski was playing for the Whites even though he was in his third year with the team, as he was still considered a second-stringer. Despite the snafu in the intra-squad game, he’d earn the starting center job in 1948 and stay with the Browns through 1956. He’d be elected to the Hall of Fame in 1985.

Brown was accustomed to seeing Willis do the kind of thing he did to Gatski and Lahr in the Browns vs. Whites game. He may have been the quickest defensive lineman in professional football. A quiet man off the field, he was called “Deacon” by his teammates, and he’d delivered a sermon on race relations to a Methodist church in Bowling Green during training camp. Once the coin was flipped on game day, however, Willis was transformed into a “a vicious, panther-like beezark, with perfect co-ordination in every sinew,” in the words of Yonkers. He spent his entire eight-year career with Cleveland, earning all-AAFC honors each of the four years the league existed, and twice being named to The Sporting News’ combined all-AAFC/NFL squad. He was a three-time Pro Bowl selection, and three-time all-league selection, after the Browns joined the NFL in 1950. Willis was elected to the Hall of Fame in 1977.

With the scrimmages behind them, the Browns began preparing for their first exhibition game, against the Buffalo Bills in Akron’s Rubber Bowl on August 22. The Bills had a pair of exhibitions under their belts, having tied the New York Yankees, 28–28, and beaten the Brooklyn Dodgers, 21–19. The victory over the Dodgers was sheer luck, as both teams scored three touchdowns, but Brooklyn missed a pair of extra points. The deadlock with the Yankees made AAFC fans sit up and take notice. Exhibition games were taken far more seriously in 1948 than today, and the Yankees were two-time defending eastern division champions. The Browns had dispatched the Yankees in the 1946 and 1947 AAFC championship games by a composite score of 28–12. The Bills ran up 478 yards of total offense against the second best team in the league. Their defense, however, allowed 458. The Browns sent assistant coach Dick Gallagher to scout Buffalo’s game with Brooklyn, and he had a concise report for the press.

“They are rough. Seriously, they are,”18 insisted Gallagher of a team that had finished in second place in the AAFC east with an 8–4–2 record in 1947. Chief scout John Brickels watched the Bills exhibition loss to the New York Yankees and was impressed. “They are truly a good-looking ball club, even at this stage of the season,” Brickels reported. “They out-played the Yankees in all departments and should have won the game. They had the ball on the Yankee three-yard line when the game ended.” Brickels didn’t say why Buffalo coach Lowell (Red) Dawson didn’t order a field goal attempt from point-blank range to win the game, and instead allowed the clock to expire with his offense inside the New York 5. Brickels continued, “They are a team that can score from anywhere on the field. If you ask me, our exhibition with them will be a real dogfight.”19

Brown said he was happy to have strong opposition for his team’s first exhibition. He elaborated upon what he hoped to accomplish.

We’ve about made up our minds to specialize with offensive units more than we ever have before. But we’re not ready to make a few decisions regarding our personnel. Sunday, it will be a case of everybody working on offense and everybody getting a chance on defense. We don’t want anyone on this team getting the idea he’s a specialist this early in the season. Everybody is going to learn all phases of our offense and defense before he is assigned a specific job.

Judging from the reports I’ve had on the Bills, the game Sunday should be very helpful in determining which of our players will work best on defense.20

Brown had no comment on a story from Brooklyn that Dodgers general manager Branch Rickey was suggesting the AAFC almost double its schedule to 26 games in 1949. “I’m withholding my comments on that until after I see what happens to us Thanksgiving week. That should show pretty conclusively whether or not a football team can play two games a week, which would be necessary under Rickey’s proposal.”21 As a forerunner of an expanded schedule, Rickey had arranged for the 1948 AAFC schedule to include a rugged eight-day span during which the Browns would play three games on both coasts. The road trip would begin with a game against the Yankees in New York, then games in Los Angeles and San Francisco. All within the span of 192 hours.

“With [Rickey’s] baseball background, he thought that a football team could play more than one game a week,” explained Brown in his autobiography. “And though I voted against it in our league meetings, he convinced enough owners to give it a try.”22

If the Browns managed to survive that grueling stretch come November, it would be partially because of the team’s spirit, exemplified by halfback Edgar (Special Delivery) Jones. If it seems like the Browns had a lot of halfbacks in 1948, they did, and Jones may have been the best of the lot. Jones had made a believer of Indians owner Bill Veeck when he was given a tryout as a pitcher during the winter of 1947–48. He didn’t show enough to be offered a baseball contract, but he still impressed Veeck with his attitude. “You’ve got to give a fellow with so much exuberance a lot of consideration,” said Veeck, who was himself a fellow known for an abundance of exuberance. “Edgar gets a big thrill out of everything he does. He seems to enjoy life so much, I actually believe he got some pleasure out of that cracked elbow he had last fall.”23

Veeck’s decision to give Jones a try-out may not have been another of his famous publicity stunts. Jones pitched in high school in his hometown of Scranton, Pennsylvania, and told Harold Sauerbrei of an exhibition game played between an amateur team from Scranton and the St. Louis Cardinals in the summer of 1937. Jones did the pitching for Scranton and held a 2–1 lead after seven innings. He’d struck out Pepper Martin, Mickey Owen, and a trio of future Hall of Famers in Leo Durocher, Johnny Mize, and Joe Medwick (Durocher is in the Hall of Fame as a manager, not for his playing prowess). Jones had held the Cardinals to four hits through seven innings, and retired the first two batters in the eighth. He then buzzed a fastball too close to Medwick’s head. Medwick wasn’t about to take that kind of treatment from a 17-year-old kid and sprinted to the mound with his bat still in his hand. Jones managed to avoid a physical confrontation, but did get a stern lecture from Medwick. He was so unnerved that he plunked Medwick in the hip with his next pitch. Jones then made a beeline for centerfield and let a teammate finish the game. He didn’t say whether Scranton won or lost. He chose to concentrate on football and starred at the University of Pittsburgh and played one game for the Chicago Bears (against the Cleveland Rams, ironically) before joining the Browns.

Jones would give Browns fans some big thrills with his performance on the field in 1948. “There is a lot of spirit on this ball club. Edgar creates plenty of it,” said Brown. “He reminds me of a rookie fighting for a chance to make the grade.”24 Jones, however, already had the grade made.

Two platoon football was slowly coming to the professional ranks, and Brown was embracing it. Most of his players had played on offense and defense during the championship season of 1946, including Otto Graham (quarterback/defensive halfback) and Marion Motley (fullback/linebacker). Both players went both ways periodically in 1947, and Brown wanted each to be able to concentrate exclusively on offense in 1948. Graham would play in the defensive backfield only in an emergency, and Motley would stay on the bench and rest when the Browns were on defense thanks to the emergence of Tony Adamle at linebacker.

“Tony has proven to me that he can handle the defensive duties,” Brown said. “He has come along fast since last year at this time, and he’s ready to relieve Motley of the added responsibility.”25 Motley’s 889 rushing yards in 1947 ranked third in the AAFC, behind Spec Sanders of the Yankees and John Strzykalski of the 49ers. Brown was convinced that having to play 60 minutes took some of the spring out of Motley’s legs by the fourth quarter and robbed him of his trademark explosiveness late in a game. Thanks to Adamle, Motley would be as fresh as a player could be in the game’s final 15 minutes in 1948.

The award for the most unusual injury suffered during the Browns’ stay in Bowling Green went to center Mel Maceau, who was awakened one night by loose plaster falling from the ceiling of his dormitory room. Fortunately, nothing fell on his head, but one large chunk fell on Maceau’s foot, bruising a toe. Maceau would be the Browns’ third-string center.

Yonkers believed the exhibition game against Buffalo would go a long way toward determining which tackles would stick with the Browns in 1948. Offensively, he felt the team was set. Defensively, at least in Yonkers’ mind, questions needed to be answered, such as how mobile was Chubby Grigg? To date, he didn’t think Grigg had shown himself to be as agile as Brown wanted his defensive linemen to be. Yonkers thought Grigg had done nothing more than squat in position and dare the offensive line to dislodge him, and he had to prove he could do more than take up space.

Another hopeful on the defensive line, Len Simonetti, was nicknamed “Meatball.” Yonkers thought “Butterball” was more appropriate. Simonetti reported to camp overweight and out of shape, not a good idea when one wished to play for Paul Brown. Having played for Cleveland in 1947, he should’ve known better. He tried to sweat off the weight by wearing a rubber shirt during practice on the hot northwestern Ohio August days, without much luck. Simonetti would make the team and play in all 14 games, but not be a major contributor.

Veteran Chet Adams was back for his eighth professional season, but he’d celebrate his 33rd birthday in October, and Yonkers expressed doubt that Adams’ legs would hold up through a full 14 games worth of pounding. Yonkers thought Brown might shift Willis from guard to tackle, but felt Willis was too light to play the position.

On August 21, the Chicago Cardinals had little difficulty defeating the college All-Stars, 28–0, before a crowd of 101,220 in Soldier Field. That was about three thousand fewer people than would attend seven Chicago Rockets home games in the same venue during the 1948 AAFC season. The group of collegians the Cardinals faced was described by the United Press as the greatest collection of college stars in the game’s 15-year history, yet the professionals barely broke a sweat in beating them. The four-touchdown margin of defeat was the widest in the game’s history.

The defending NFL champs scored in the first quarter on a two-yard run by Elmer Angsman, capping an 80-yard march against the best defenders college football had to offer. An 85-yard second quarter drive ended when Vic Schwall ran 14 yards for a score and a 14–0 lead at halftime. In the fourth period, Vince Banonis intercepted a pass by Perry Moss and returned it 30 yards for a touchdown, and back-up quarterback Ray Mallouf ended the scoring with a 13-yard pass to Charley Trippi. The All-Stars threatened once, driving 85 yards to the Cardinals’ one-and-a-half-yard line before surrendering the ball on downs.

“We appreciate the co-operation we have received from most of the teams in the National Football League, and all of the teams in the All-America Conference,”26 said Arch Ward, the game’s founder. Ward’s newspaper, the Chicago Tribune, sponsored the exhibition, which had raised hundreds of thousands of dollars for charity. The one NFL team which hadn’t cooperated was the Washington Redskins, whose prize rookie, quarterback Harry Gilmer from the University of Alabama, declined to participate after signing an agreement to do so. The NFL’s contract with the Tribune required any player invited to play for the All-Stars take part in the game unless released from that obligation in writing. Gilmer wasn’t released, but declined to report to the All-Stars, who were paid for their participation, saying he feared a career-threatening, or career-ending injury, against which he wasn’t sufficiently insured by the Tribune. It wasn’t known if Gilmer came to that conclusion on his own, or was prodded by Redskins owner George Preston Marshall. Weeks of legal wrangling ensued, and the AAFC made it known that if the Tribune decided to cancel its contract with the NFL over the Gilmer affair, the younger league would be happy to have its champion play the collegians in 1949 and beyond. The spat between the newspaper and the NFL didn’t reach that point.

Among those taking in the all-star game was former NFL commissioner Elmer Layden, who had sniffed, “Let them get a football!” when first informed that a rival league was forming back in 1945. Asked about the chances for a conciliation between the NFL and AAFC, Layden said, “The two leagues should get together. For the National League to keep fighting them is just throwing money away.”27 Much would be said, and written, about the possibility of a peace accord between the two leagues throughout the 1948 season.

The Browns had little trouble with Buffalo on August 22, jumping to a 28–0 lead and coasting to a 35–21 victory before a crowd of 28,069 in the Rubber Bowl. Cleveland played without left tackle John Prchlik and halfback Ollie Cline, who had just returned from two weeks with the college all-stars and were too far behind their teammates in terms of having learned the team’s playbook to take the field.

Defensive back Cliff Lewis got the Browns off to a quick start by returning an intercepted Buffalo pass 60 yards for the game’s first score in the first quarter. An Otto Graham to Dean Sensabaugher pass increased the lead to 14–0, and then Graham hooked up with end Mac Speedie on an 80-yard catch and run (30 yards through the air, 50 yards after the catch) to boost the margin to 21–0. Graham sat out the game’s final three quarters.

Lewis, who doubled as Graham’s back-up, connected with Sensabaugher on a 41-yard touchdown play that gave the Browns a 28–0 lead, and a 39-yard pass from Lewis to Dante (Gluefingers) Lavelli set up Marion Motley’s one-yard plunge for Cleveland’s last score. Lewis then took a seat next to Graham on the bench and Warren Lahr finished the game at quarterback. Lahr didn’t put any points on the board, but the Browns didn’t need any.

“Lahr was green, but I think he did all right,” said Brown after the game. “We think he has the makings.”28

Buffalo scored on touchdown passes to Alton Baldwin and Bill O’Connor and a 100-yard punt return by Rex Bumgardner and Bill Heywood. Bumgardner caught Horace Gillom’s punt on his goal line and swerved 80 yards through the Cleveland punt coverage unit, the unit Brown had devoted an entire day’s practice (in the rain) to improving. With the defense closing in on him, Bumgardner lateraled the ball to Heywood, who lugged it the final 20 yards for the touchdown. Ironically, Bumgardner would gain only 82 yards on 13 punt returns during the season, but he impressed Brown sufficiently that, when the Bills disbanded after the 1949 season, Cleveland grabbed him.

Statistically, the Browns gained 365 yards to Buffalo’s 333. Each team rushed for 206 yards. That pleased Brown offensively, but didn’t please him defensively. Cleveland gained 159 yards passing to 127 for the Bills. The Browns threw a dozen passes and completed just five. The Bills threw the ball 31 times and completed 11.

After the game, Brown encountered an old acquaintance in the runway outside the Browns’ dressing quarters. New York Yankees assistant coach Norman (Red) Strader was prowling around after watching the contest. “Fancy meeting you here, Red,” said Brown with a grin. “Don’t tell me you’re scouting us already. I didn’t think Ray Flaherty and Dan Topping were even concerned about the ‘hicks from the sticks.’ Just send ’em an SOS, Red. Tell ’em we’ve got the same old stuff.”29 Flaherty, the Yankees’ coach whose NFL playing and coaching days dated back to 1933, had called the Browns “a Podunk team with a high school coach.” Brown never forgot the comment. The team from Podunk, and its high school coach, had defeated Flaherty twice in the AAFC championship game, and Flaherty knew the road to the 1948 championship ran through Cleveland. He was going to make sure he had all the information on his team’s chief nemesis that could be gathered.

There were a lot of coaches nicknamed “Red” in the AAFC. One of them, Bill (Red) Conkright, had been an assistant with Cleveland in 1946 before moving on to Buffalo. Conkright was grateful his team didn’t play in the AAFC’s western division after their exhibition loss to the Browns, and he didn’t hold out much hope for the Bills to win either of the two regular season meetings between them. “Even though we didn’t look too good today, we don’t belong in the same class with the Browns,” lamented Conkright. “We’d have to be awfully lucky to beat them.”30 The Bills would get three more chances to do that in 1948.

With the Browns having run roughshod over the competition since their inception, Brown was always careful to make sure his players never got cocky or overconfident. He was stinting with his praise after each victory, and he said he saw plenty of mistakes while viewing the film of the game against Buffalo. “We were not only good and lucky, but we got also got a break in that George Ratterman, their quarterback, wasn’t up to par because of a bad cold. He was so bad before the game that they feared pneumonia.”31

Early in training camp, Dick Gallagher, the Browns’ defensive line coach, felt he needed another quality end. The day after the victory over Buffalo, the Browns tried to accommodate Gallagher by purchasing the contract of Frank Kosikowski, a six-foot, 200-pound end from the Bills. Kosikowski had played on Frank Leahy’s 1947 national championship Notre Dame squad. Kosikowski would compete with Ray Elbi, who’d been obtained by the Browns on August 19 from the Rockets, Tod Saylor and Roy Kurrasch for the one available position on Cleveland’s defensive line.

The Browns reported on August 19 that they expected to sell 16,000 season tickets before the team’s regular season opener on September 3. If that figure proved to be accurate, it would represent a 60 percent boost in season ticket sales over 1947. And Cleveland had led all of professional football in attendance the previous year.

For the first time since 1944, Don Greenwood wasn’t involved in a Cleveland professional football team’s training camp. Greenwood was a member of the 1945 NFL champion Rams, then opted to stay in Cleveland when the Rams moved to Los Angeles. A serious injury sustained late in the 1947 season forced Greenwood to retire, and he was preparing to coach the Cuyahoga Falls high school team while the Browns were preparing for the AAFC season.

Said Greenwood of the man he hoped to emulate, Paul Brown, “What most people don’t realize is that in the past 2½ years, he has theorized and effected an offense that is different from, and more effective than, any previously employed.”32 The Browns had scored 423 points in 1946 and 410 in 1947, for an average of 29.8 per game. Few teams had ever possessed weapons like Graham, Motley, Speedie and Lavelli, and Brown knew how to maximize their productivity.

Brown trimmed his roster to 40 players on August 25 by waiving ends Saylor and Elbi. Elbi had two strikes against him when he reported to Bowling Green as he arrived suffering from a sprained ankle. It took Brown only five days to decide Elbi didn’t have what it took. That left Kosikowski and Kurrasch to battle for one roster spot, backing up John Yonakor.

Edgar Jones and Bob Brugge wouldn’t be available when the Browns met the Baltimore Colts at Scott High School in Toledo in the second and final exhibition game on August 27. Jones sustained a torn cartilage during the game with Buffalo, and Brugge had a hamstring injury that dated back to his playing days at Ohio State. “Bob just can’t run,” said Brown, “and we reached an agreement today that will give a chance to work this thing out.”33

Brown’s plan was to place Brugge on waivers, then hope none of the seven AAFC teams would claim him, meaning he’d join the Browns as soon as his injury healed. Why Brown thought the rest of the AAFC would do him such a favor isn’t clear. If Brugge was claimed, Brown would withdraw the waivers and place him on the injured reserve list. He’d be ineligible to play for 60 days. Brugge’s end of the bargain called for him to return to Ohio State to continue his education and follow a training program created by Browns trainer Wally Bock, designed to cure his hamstring problem and prepare him for football. Brugge would never wear a Browns uniform.

Baltimore brought an 0–2 record into its exhibition against the Browns. The Colts played both games on the west coast, losing to the Dons in Los Angeles, 28–21, and the 49ers in San Francisco, 42–14. According to the United Press, the Colts looked miserable against the 49ers. “The eastern team showed little in the way of offense,” said the wire service’s summation, “and failed to threaten the 49er goal line until San Francisco’s first-stringers left the field.” The Colts’ defense did no better. San Francisco quarterback Frankie Albert completed 11 of 14 passes against the Baltimore defense. Five were for touchdowns.

Former NFL star Cecil Isbell, in his second season as coach of the Colts, admitted that his team lacked depth and said he’d need a few more years to mold a contender on Chesapeake Bay. But the Colts didn’t play like an also-ran on a sweltering late August night in Toledo. Temperatures flirting with 100 degrees held the crowd down to 13,433. That was unfortunate since the proceeds were being donated to the Toledo Times welfare fund, and the Downtown Coaches Association’s scholarship fund.

Those who braved the tropical conditions watched the Colts overcome an early 10–0 deficit and hand the Browns their only defeat of 1948, 21–17. The Colts were led by rookie quarterback Y.A. Tittle, who’d been the sixth overall pick in the 1948 NFL draft by the Detroit Lions. Tittle chose to cast his lot with the Browns, only to have Brown trade him to Baltimore as part of the AAFC’s plan to strengthen weak teams (such as the Colts) by having strong teams (such as the Browns) trade unnecessary players for minor considerations. As promising as Tittle was, he wasn’t going to supplant, or even seriously challenge, Graham for Cleveland’s starting quarterback job. Brown hated to part with Tittle, but he was expendable, and it was for the good of the league. Still, it was painful for Brown to watch Tittle rally the Colts with touchdown passes to Jake Leicht and Lamar Davis, and a 29-yard strike to Billy Hillenbrand in the fourth quarter that was followed by Bus Mertes’ 38-yard run for the winning score.

The Browns had drawn first blood on an 18-yard field goal by Lou Groza just four minutes into the contest. Ollie Cline, substituting for an injured Marion Motley, accounted for the Browns’ touchdowns with runs of eight and 23 yards. Cleveland led 17–7 in the second quarter, but didn’t score in the second half with Graham on the bench. Motley pulled a muscle in the first period and didn’t return, and Graham injured his throwing hand in the second quarter. A far more serious injury was suffered by end Dante Lavelli, also in the second quarter.

Lavelli limped off the field after being tackled with what was originally thought to be a sprained ankle. A closer examination showed the injury to be a fractured tibia of Lavelli’s right leg. He’d miss at least six weeks.

The Browns lost despite amassing 22 first downs to only seven for the Colts. Cleveland gained 451 yards to 402 for Baltimore. The Browns had the advantage on the ground, 187–107, but the Colts had the advantage through the air, 295–264.

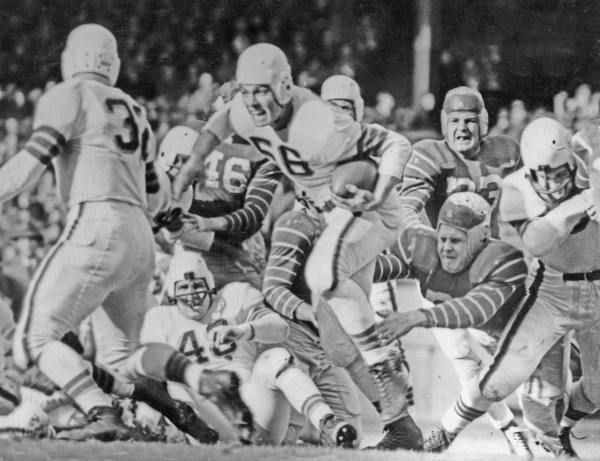

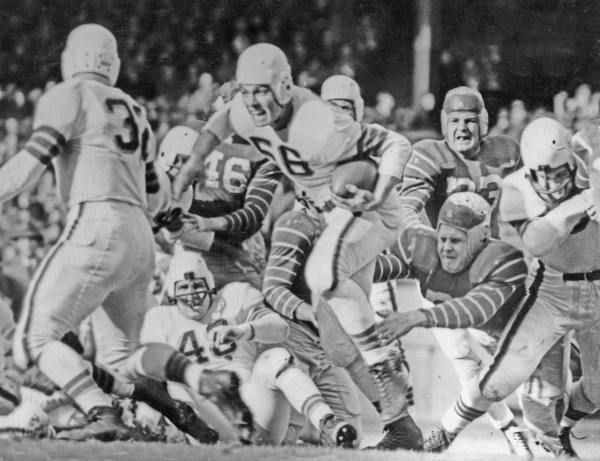

Hall of Fame receiver Dante Lavelli gains yardage in a 1950 game versus Philadelphia.

A grim Brown talked to reporters after the game. “It was a stiff penalty for us to lose Lavelli,” he said. As for the defeat, the coach said, “We got licked. It just goes to show what happens when you think you’re going to have an easy time of it, and run into a club that’s all coked up for you.”34 As long as the game didn’t count, the defeat may have been the best thing that could have happened to the Browns. Although their coach was a master psychologist, the players wouldn’t have been human if they hadn’t fallen prey to at least slight feelings of invincibility after piling one victory upon another for two full seasons, and heading into a third, despite Brown’s best efforts to keep them focused on the task at hand. With exhibition games being taken more seriously in 1948 than they are today, the loss to the Colts may have been just the tonic the Browns needed as the regular season beckoned.

While the Browns were playing an exhibition game, four AAFC teams were kicking off their regular seasons on that Friday night, and three new coaches made their debuts in games that counted. In Chicago, where it was just as hot as it was in Toledo, the Dons won a yawner over the Rockets, 7–0. The lack of offense was attributed to the draining effect of the intense heat and humidity on the players. It was the first game for two AAFC coaches, Ed McKeever of the Rockets and Jimmy Phelan of the Dons. Bob Yonkers thought McKeever could make the Rockets a threat to the Bears and Cardinals for fan loyalty (and ticket dollars) in Chicago. Yonkers said the Rockets had the talent to be competitive, but lacked proper coaching in 1946 and ’47. He thought McKeever would provide that coaching. He’d prove to be wrong, either about McKeever, or about the talent on hand in Chicago, or possibly both.

In Brooklyn, the Yankees picked up where they’d left off in 1947, defeating the Dodgers, 21–3. That game marked the head coaching debut of Carl Voyles of Brooklyn. Voyles had been hired by Branch Rickey from the collegiate ranks. Two days later, the 49ers would open their season at home with a 35–14 thumping of the Bills.

Following the Baltimore game, Brown asked waivers on John Prchlik, the tackle from Yale who was also a native Clevelander. Brown was partial to players from Ohio, provided, of course, they had talent. The time Prchlik spent out of camp with the college all-stars may have damaged his chance to make the squad, although halfback Ollie Cline, who was also an all-star, earned a roster spot. Paul Goll, Ed Sustersic, and Roy Kurrasch were also cut. Kurrasch’s release meant Frank Kosikowski had won the competition to be Yonakor’s back-up at defensive end. The Browns had the 35 players they’d try to successfully defend their AAFC championship with.

The preliminaries were over. Not even the most optimistic of Browns fans would’ve suggested as the team walked off the Scott High field on that sweltering late August night, following the defeat to Baltimore, that they had lost the only game they’d lose for the season. And it hadn’t counted.

The next 15 games would.