Browns 19, Dons 14

This wasn’t the way Paul Brown, or any other head football coach, wanted to begin the week of preparation for the season’s first game.

When Dante Lavelli limped off the field at Toledo Scott high school on August 27, it was assumed he’d sustained a sprained ankle. While a significant injury, it was hoped Lavelli would be able to play against the Los Angeles Dons in the season opener in Municipal Stadium a week later. That hope proved to be far too optimistic.

X-rays showed Lavelli’s injury to be a fractured tibia of the right leg. If he was on the sideline at Municipal Stadium for the match-up with the Dons, he’d be wearing street clothes with his leg in a cast, and giving moral support to his teammates. At the very least, Lavelli would miss the first six weeks of the season. Brown’s plan was to place Lavelli on the 60-day injured-retired list and keep ends Roy Kurrasch and Frank Kosikowski. The plan was abandoned when Brown was reminded of an AAFC rule stating that any player placed on the injured-retired list at any point in the year was ineligible to play during the final 30 days of the season if subsequently activated. Brown certainly wanted Lavelli available in November and December if his leg had healed sufficiently by then. Lavelli had to remain on the Browns’ active roster even though he couldn’t play, leaving the team with five offensive ends. Brown then decided to shift Horace Gillom from left offensive end to right, substituting for Lavelli. A bad break for Lavelli had the potential to be a very good one for Gillom.

Called by Brown “the greatest high school player I ever coached,” when he arrived at the Browns’ training camp in 1947, from the University of Nevada (via Ohio State), Gillom displayed startling ability as an end with a series of circus catches that ranged from one-handed grabs, to catches made off his shoe tops, to passes batted in the air deliberately by Gillom to buy him time to elude the defensive back covering him before he caught them. Unfortunately for Gillom, he had a hard time learning Brown’s intricate pass routes and blocking assignments, and couldn’t crack the team’s regular receiving corps. He was relegated to punting duty, and was the best in the AAFC at it. Brown gave some thought to using John Yonakor as Lavelli’s replacement rather than Gillom. Yonakor had been a star receiver in college, but lacked the speed to play the position in the pros. Since Brown was leaning toward two-platoon football, he preferred to utilize Yonakor exclusively as a defensive end. Gillom would line up in Lavelli’s spot on offense.

Gillom couldn’t be blamed if he was slightly distracted in the days leading up to the Browns’ opener. His wife gave birth to a nine-and-a-half-pound baby boy in Massillon on September 1.

The injury reports on Otto Graham and Marion Motley weren’t nearly as dire, but Brown said the team’s medical staff gave him no assurance that either his star quarterback or his star fullback would be at 100 percent physically for the opener. The game against Baltimore had been rough.

After six weeks in Bowling Green, 35 men had earned the right to wear the orange, brown and white. The 1948 Browns, and their uniform numbers, were, using the terminology of the era, as follows:

Centers: Lou Saban (20), Gunner Gatski (22), Mel Maceau (24)

Guards: Bill Willis (30), Lindell Houston (32), Bob Gaudio (34), Alex Agase (35), Ed Ulinski (36), Weldon Humble (38)

Tackles: Chet Adams (42), Lou Rymkus (44), Ben Pucci (45), Lou Groza (46), Chubby Grigg (48), Len Simonetti (49)

Ends: John Yonakor (50), George Young (52), Frank Kosikowski (53), Dante Lavelli (56), Mac Speedie (58), Horace Gillom (59)

Quarterbacks: Otto Graham (60), Cliff Lewis (62), Warren Lahr (66)

Fullbacks: Ollie Cline (70), Tony Adamle (74), Marion Motley (76)

Halfbacks: Bob Cowan (80), Tommy James (82), Ara Parseghian (85), Dub Jones (86), Edgar Jones (90), Tom Colella (92), Dean Sensabaugher (94), Bill Boedeker (99)

Agase, Cline, Lahr, Kosikowski, James, Parseghian, Dub Jones, Sensabaugher, Grigg and Pucci were in their first year with the Browns. The other 25 players had contributed to varying degrees to the team’s 1947 championship.

The Browns had lost just three games in the first two years of the AAFC, and two of the losses were at the hands of their opening night opponent, the Dons. Los Angeles was coached by former Notre Dame quarterback Jimmy Phelan, who replaced co-coaches Mel Hein and Ted Shipkey after the 1947 season. Hein and Shipkey had taken over for Dudley DeGroot, the Dons’ first head coach, who departed 11 games into the 1947 campaign. Perhaps showing his inexperience, the 55-year-old rookie coach said he planned to have his team spend five days practicing at the Cedar Point resort in Sandusky, some 75 miles west of Cleveland. He changed his mind after learning the Elks were holding a convention at Cedar Point. “I knew there wouldn’t be much sleeping with the convention boys celebrating, so I decided we’d be better off in Cleveland,”1 said Phelan. Maybe Phelan, being a Notre Damer, knew that Knute Rockne and Gus Dorais, while working as lifeguards at Cedar Point in the summer of 1913, had practiced the formerly rarely used offensive weapon known as the forward pass on the resort’s beach during their free time. Phelan may have hoped some of the Rockne magic would rub off on his team.

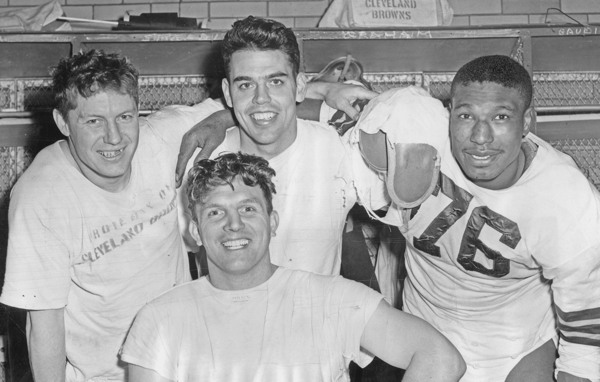

Four important contributors to the Browns' undefeated 1948 championship season (left to right): Edgar Jones, Otto Graham, Marion Motley and Lou Saban.

Phelan said he expected the Browns’ exhibition loss to the Colts to put them in a surly mood. “Well, one thing I’m sure of is that Paul Brown will have plenty of fuel to fire his team with this week,”2 he said. “We’re in good shape, and we hope to give your Browns a good rassle.”3

Of the Dons’ offense, which had been held in check by the Rockets in the season opener the previous week, Phelan explained, “I’m still using the single wing, and I think our material is ideally suited to that type of offense. [Quarterback] Glenn Dobbs and Herman Wedemeyer are a pair of the best triple threat backs that a coach could ask for. In fact, it seems a shame that they can’t both be used at once, and we’re going over that possibility now. It pleased me that [fullback] John Kimbrough gave up his thought of retiring. I think he will be better than ever back in the single wing. I’m optimistic about this football season we’re opening this Friday [the Dons had already opened their season]. But the only prediction I can make is that the Dons will play interesting, colorful football.”4

The Dons hadn’t lived up to that prediction in their opener, gaining just 97 yards in their 7–0 victory in Chicago. “That’s right,” admitted Phelan, “we gained 77 yards on the ground and 20 by passing, and most of that was made when we went straight down the field in nine plays for the game’s only touchdown.”5 Ninety-seven yards and one touchdown weren’t going to beat the Browns, and Phelan knew it. “We’ve got to show a lot more scoring punch if we hope to beat the Browns,”6 he admitted after putting the Dons through a one-hour workout on the Municipal Stadium turf on August 30.

Brown wouldn’t be lulled into a false sense of security by the Dons’ poor offensive showing against the sad-sack Rockets. “We respect the Dons in every way,” he said. “They are big, strong, and have the know how.”7 Of Dobbs, he said, “He’s capable of wrecking almost any team all by himself almost any time.”8 Brown and his coaches were working on a defensive strategy to make sure Dobbs didn’t single-handedly wreck the Browns.

Lou Groza wasn’t one of the team’s 10 new players, but he was a new starter on the offensive line. Another of Brown’s beloved Ohio State products, Groza spent most of his time kicking extra points and field goals in 1946 and ’47. Groza led the AAFC in scoring in 1946 with 84 points on 45 conversions and 13 field goals (in 29 attempts). A pulled muscle Groza suffered during a pre-game warm-up in 1947 limited his effectiveness, and his production declined to 39 PATs and just seven field goals (in 19 tries). Although he’d retire as the NFL’s all-time leading scorer with 1,349 points (the NFL still doesn’t recognize the 259 points Groza scored in the AAFC) and earn the nickname “Lou the Toe,” his field goal accuracy left a great deal to be desired by modern standards. Like all place-kickers of his era, Groza kicked straight ahead, and often at severe angles, which have long since been eliminated by rule changes. Groza converted only 30 of the 76 field goals he attempted in the AAFC, yet was considered one of Cleveland’s prime offensive weapons. The field goal was largely an afterthought until Brown made heavy use of Groza’s leg. By the time the Browns joined the NFL, Groza’s accuracy had improved markedly, and he retired having converted 54.9 percent of the 481 field goals he attempted (including the 76 he tried in the AAFC). Groza led NFL kickers in field goal accuracy five times and was successful on 88.5 percent of his 26 attempts in 1953. Groza made the field goal a viable offensive weapon in professional football.

Brown was asked at the close of training camp if Groza’s progress as a lineman justified his new status as a starter. “He doesn’t have to make much progress,” Brown, a notoriously tough taskmaster, answered. “We have always known that he could play football. He’s agile, fast and a good blocker. I’d say he was about the same as he was last year, and he was a pretty good football player then.”9 Groza was good enough to be selected to the Pro Bowl nine times and earn All-Pro honors four times. He was elected to the Hall of Fame as both a lineman and a place-kicker in 1974. Perhaps more importantly, he was probably Paul Brown’s favorite player. Brown often affectionately referred to Groza as “my Louie.”

Groza had lost the title of professional football’s best kicker to Ben Agajanian of the Dons in 1947. Agajanian booted 15 field goals in 24 attempts, and missed just one of his 40 extra points. Groza wanted the title back.

The Browns ate well during the final days of training camp, thanks in part to the generosity of Tommy Henrich. Henrich, an outfielder with the defending world champion New York Yankees , endorsed a popular breakfast cereal. In return, the cereal maker rewarded Henrich with a case of its product after every home run he hit. That left Henrich with more cereal than he could eat, so he promised his old Massillon neighbor, Paul Brown, that he’d send the cereal he’d receive for his 16th home run to Bowling Green to feed Brown’s hungry football players. Brown agreed, on one condition. “That’s a deal, unless you make the homer against the Cleveland Indians,” he told Henrich. “We’ll have no part of any cereal on a blast that might hurt Cleveland.”10 The Indians were battling Henrich’s Yankees and the Boston Red Sox for the American League lead in early September. Henrich’s 16th homer was smacked against the Detroit Tigers, so breakfast during the closing days of training camp was on him. The notoriously frugal Brown probably appreciated the chance to save a few dollars on training table expenses.

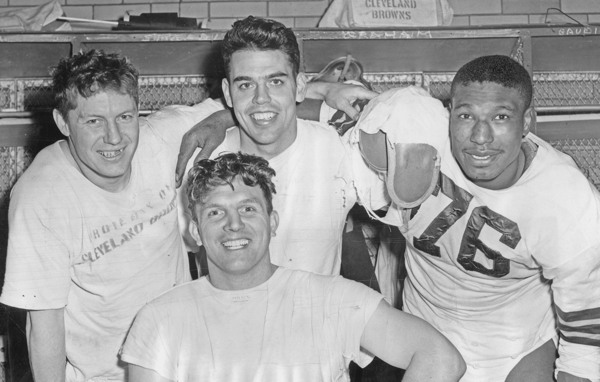

Paul Brown with his favorite player, the man he called "my Louie," Hall of Fame offensive lineman and placekicker Lou Groza.

The Browns broke camp on September 2. That afternoon, the Cleveland Touchdown Club held its first meeting of the year at the Carter Hotel. Brown was to be the master of ceremonies, with Jimmy Phelan the guest speaker. A crowd of 450 was anticipated.

Brown told the Touchdown Club that the exhibition loss to the Baltimore Colts had taken a physical toll on his team. “We won’t know just how good Otto Graham and Marion Motley will be, and added to that is the fact that Cliff Lewis, Mac Speedie and Tommy Colella all have minor injuries. I never have coached a team before that took the physical beating in one game that this one took last week, and I never had a team start a season with so many injured players.”11 The woeful Colts apparently decided that if they couldn’t beat their opponents, they’d at least beat them up. The physical beating the Browns took from Baltimore left an impression on Brown. He told the luncheon that he planned to schedule just one exhibition game in 1949, in the hope of avoiding the kind of bumps and bruises (and broken tibias) inflicted by the Colts in a meaningless game.

Brown also told the Touchdown Club that Ollie Cline would start at fullback if Motley couldn’t answer the bell. As it turned out, Cline didn’t get off the bench until mid-way through the fourth quarter.

On a lighter note, Brown poked fun at his fondness for players from Ohio in general, and Ohio State in particular. “The boys on the squad were talking one night about making a team out of Ohio State alumni, and they could pick 11 from the crowd training at Bowling Green—including a coach.”12

One player who was neither from Ohio, nor played at Ohio State, but still starred collegiately in Cleveland was honored at the luncheon. Warren Lahr was presented with a trophy designating him as the most valuable local college player of 1947 for his performance with Western Reserve University. Lahr was one of the many Browns who’d been banged up by the Colts. He wouldn’t see the field in a Browns uniform in 1948.

For those who weren’t able make it to Municipal Stadium, Browns games were broadcast on radio on WGAR/AM. Bob Neal and Bill Mayer were the announcers. They’d enjoy the pleasant task of broadcasting 15 consecutive victories. Among the stations on the Browns’ radio network were WBNS in the state capital of Columbus; WHIO in Dayton; WATG in Ashland; WTRF in Bellaire; WFRO in Fremont; and WJEL in Springfield. The Browns would eventually build a vast radio and TV network stretching deep into the southern states. Future baseball home run king Hank Aaron made no secret of being a Browns fan, having started by watching their games on television as a youngster. The Browns were America’s team long before the Dallas Cowboys were.

The odds makers established the Browns as seven-point favorites to win their season opener. They failed to cover the spread, but won the game.

Cleveland opened its defense of its All-America Football Conference title with a 19–14 triumph over the Dons on September 3. The contest wasn’t as close as the score suggests. The Browns led, 19–0, until the final 30 seconds.

Cleveland opened the scoring with a 51-yard field goal by Groza that stretched the limit of his range. It was the second 51-yard boot of Groza’s career and barely cleared the crossbar. In 1948, the goal posts were on the goal line and not at the back of the end zone as they are today. Groza was called upon to try a 55-yarder later in the contest. It would have been the longest field goal in professional football history had he converted.

The Browns’ first touchdown drive of the season, in the second period, covered 69 yards. A pair of runs by Edgar Jones gained 16 yards, Motley rumbled for 19 more, and Graham hooked up with Bob Cowan for a 30-yard gain. The final 21 yards were covered by a pass from Graham to Ara Parseghian. Cleveland benefited from a Los Angeles mistake in the third period when Dobbs stepped out of his end zone while fading back to pass, resulting in a safety and a 12–0 Browns lead. Speedie returned the ensuing free kick (Phelan elected to punt) to Cleveland’s 45-yard line. Graham led a 55-yard scoring march that increased the lead to 19–0, with Bill Boedeker running the ball in from five yards away.

Cleveland’s defense lost its shutout when John Kimbrough scored on a five-yard run with 30 seconds to play. The Dons then recovered the on-side kick at the Browns’ 44, and a pass interference penalty quickly moved the ball to the nine. Dobbs threw a touchdown pass to Joe Aguirre with five seconds to play. The crowd of 60,139 departed happy, if a bit shaken by the late defensive collapse. Among the throng was actor Don Ameche, who made the trip from Hollywood. Ameche was a minority owner of the Dons. However, unlike the Browns, the Dons were not named for him.

Statistically, the Browns out-gained their guests, 263–214. Graham completed nine of 17 passes for 169 yards, one touchdown and two interceptions. Dobbs was forced to pass 28 times since the Dons weren’t able to run effectively. He completed 16 for 147 yards, one touchdown and two interceptions. Motley, showing no ill effects from his injury, picked up 55 yards on 11 carries as the Browns gained 161 yards on the ground while holding Los Angeles to 69. It was a sloppily played game, and Brown couldn’t have been pleased that his normally well-disciplined team was whistled for 125 yards in penalties.

“I thought we played pretty good football out there tonight, but we were also pretty lucky,”13 said Brown in briefly analyzing his team’s first game.

Phelan took his hat off to the victors. “They’re too good and too fast for us,” said the Dons’ coach. “That’s what we need—speed in our backfield. Until we get it, we’ll have a tough time beating clubs like the Browns.”14 Phelan also tipped his cap to Graham. “I’ve seen him play before. He’s really an expert, and he’s got a lot of fine teammates, believe me.”15 To summarize, Phelan said simply, “That’s a fine team. They have too much of everything.”16

Dobbs wasn’t as impressed as his coach, and had a warning for the Browns. “It’ll be a different story when we get those guys in our ball park,”17 he snarled. Kimbrough had a warning for his teammate and quarterback. “They’ll be just as tough there, believe me,”18 said the Dons’ halfback.

Dobbs wasn’t the only Don who was certain the Browns could be beaten. The News included this quote in its game summary: “San Francisco will lick your guys. They have a lot of halfbacks who can really run.” The story didn’t say whether the quote came from an anonymous Los Angeles player, or it if represented a consensus of the opinions voiced to the writer in the loser’s locker room. The story didn’t carry a by-line.

Willis had a particularly strong game for Cleveland, recovering two fumbles and blocking a Los Angeles punt. The blocked punt went for naught, however, because Adamle, after alertly falling on the loose ball, promptly fumbled it. The Dons recovered, and both Willis and Adamle had to go right back to work on defense.

In other AAFC games that weekend, Buffalo buried Chicago, 42–7; San Francisco defeated Brooklyn, 36–20; and Baltimore upset New York, 45–28. Y.A. Tittle broke Graham’s AAFC record for passing yardage by burning the Yankees’ secondary for 346 yards. Yankees head coach Ray Flaherty would have some choice words about the defeat later in the coming week.

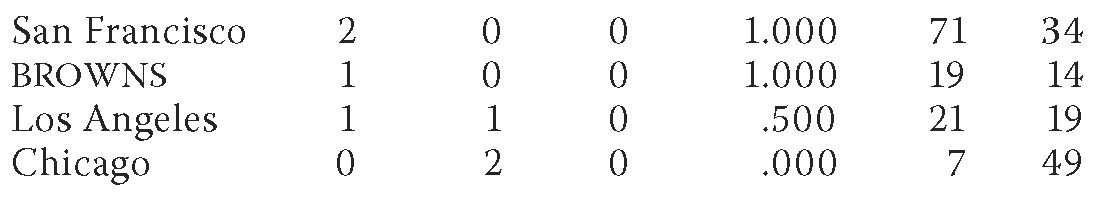

The standings in the western division after the second (but the Browns’ first) week of play:

The Browns would spend the next two weeks on the road.