Browns 31, Bills 14

What, them again?

With two victories over the Buffalo Bills under their belts in 1948, the Browns, it was feared by their head coach, might be overlooking them, considering the two teams had met five times (not counting exhibitions) since 1946, and the Browns had won each encounter. So Paul Brown turned to his chief scout, John Brickels. Brickels had warned before the exhibition match-up in August that the Bills would be a tough team. He also hit the nail on the head when he predicted that the New York Yankees, the eastern division’s best team in 1946 and ’47, looked to be on the decline.

After scouting the Bills-Yankees exhibition game that wound up in a 28–28 tie, Brickels said, “I’m predicting those New York Yankees won’t have an easy time winning that eastern division championship the way they did for two years. I like the looks of those Buffalo Bills very much.” Even though coach Red Dawson’s Bills weren’t playing nearly as well (2–4) through six games in 1948 as they were in 1947 (4–2), Brickels still liked them.

“It’s a wide open race, so don’t sell those Buffaloes short,” said the scout. “I saw them again last Sunday and they just had one of those days [a one-point loss to the Yankees], but they still don’t look too bad. I still think they’re a good football team. They gave us all we could handle for half a game at Buffalo a month ago, and made things interesting for those 49ers, too, before losing. And don’t get too excited about this Ratterman business. I look for him to be in there quite a bit on Sunday. Sometimes, these little shake-ups on a team do them some good. They’ll probably be rebounding Sunday, and it’s our luck to catch them that way. They’re a good scoring team, and that type can make an interesting afternoon for any club in the league.”1

Buffalo’s offense had gained more yardage then Cleveland’s, and quarterback George Ratterman guided an attack that had thrown for more yards than the Browns’ much more heralded Otto Graham. But, in the wake of a 14–13 loss to the Yankees the previous week, Dawson announced that Ratterman had been demoted to second string for “loafing.” According to reports from Buffalo, the 21-year-old Ratterman refused to execute plays Dawson sent in from the bench, making him guilty of insubordination. Both Dawson and Ratterman denied that. Dawson said he didn’t send any plays into the game from the sideline, so Ratterman couldn’t have refused to run them.

“I haven’t said George was insubordinate … yet. I haven’t said anything,”2 said Dawson, who then decided to say no more and hung up on the interviewer. As for Ratterman, the defrocked quarterback declared, “I am satisfied that the lies about my actions have been denied. As for being placed behind Jim Still in the quarterback position, I have no complaint. If the coach is displeased with the way I’ve been running the team, it’s his job to make the change.”3

In addition to benching Ratterman, Dawson shook things up by cutting tackle Graham Armstrong and halfback Chuck Maggioli on October 12. Armstrong had played college football at Cleveland’s John Carroll University. In his second season with the Bills, he was Buffalo’s placekicker in addition to being a starter on the offensive and defensive lines. He’d kicked 15 of 17 extra points but missed his only field goal try. Armstrong would be replaced as kicker by halfback Bob Steuber. Maggioli had been injured in training camp and carried the ball just 11 times for 27 yards.

“The move is being made for the betterment of the situation in general, and particularly for team morale,”4 said Dawson in a written statement issued by the Bills’ publicity department.

Part of the reason Graham was enjoying another strong campaign was the play of his offensive line, which gave him adequate time to throw. A new starter on that line was Clevelander Bob Gaudio, who’d played at East Cleveland Shaw High School and Ohio State. According to a study of the offensive line’s performance in 1947, conducted by Brown’s top assistant coach, Blanton Collier, the only lineman who’d executed his assignment properly more often than Gaudio had been Ed Ulinski. So when the 1948 season began, Gaudio was starting and Lin Houston was on the bench. “Lin hasn’t lost his touch,” insisted guard coach Fritz Heisler. “He’s just as good as he ever was. But this fellow Gaudio has been doing a terrific job for us, and we just can’t keep him off the field.” Heisler noted that Gaudio had played well in the victory over Brooklyn. “There was no one or two plays I noticed in particular. He just played an all-around, sound football game all the way.”5

Gaudio played on Ohio State’s freshman team in 1942 before going into the armed services. He played for the Buckeye varsity in 1946 before giving up the sport to join the family construction business. He signed with the Browns in 1947, but was given little chance to make the team due to his extremely limited experience. He proved the doubters wrong.

Cleveland’s pass defense had been as effective as the pass offense through the season’s first half dozen games, due in part to improved play by the defensive line. Chubby Grigg had emerged as one of the top defensive tackles in the AAFC. He credited the lessons he’d learned from his fellow tackle, veteran Chet Adams, who he called “one of the best defensive tackles I’ve ever seen.” Grigg said, “I’m not playing as much as I did last year [with the Rockets], but I’m in the best shape of my life. Last year I was averaging close to 60 minutes, but I still couldn’t keep my weight down.”6 Grigg reported to the Browns’ summer training camp weighing 272 pounds, and he’d stayed slim and trim as the season progressed. Due in part to the pressure Grigg and Adams were exerting on opposing quarterbacks, the Browns held Brooklyn to 94 passing yards; Los Angeles to 69; Baltimore to 87; and Chicago to 45 and 125. Only the Bills had given the Browns problems, gaining 216 yards through the air the first time the teams played in Buffalo in early September. Ratterman had accumulated those yards, and he’d be on the bench for the rematch. At least when the game started.

The Brown-to-college coaching rumors that started in September gained momentum in October. September’s rumor had him taking over the athletic department at UCLA and naming himself head football coach. On October 15, a story written by Davis Walsh of the International News Service claimed Brown would replace USC coach Jeff Cravath in 1949. Brown denied it. “I have had no contact whatsoever with officials from Southern California,” he said. “As far as I know, Southern California has a football coach. Willis Hunter, their athletic director, is a very close friend of mine and has been ever since we played them at Ohio State, but he has not approached me on the subject of going to California. Frankly, I think northern Ohio is pretty good sports territory.”

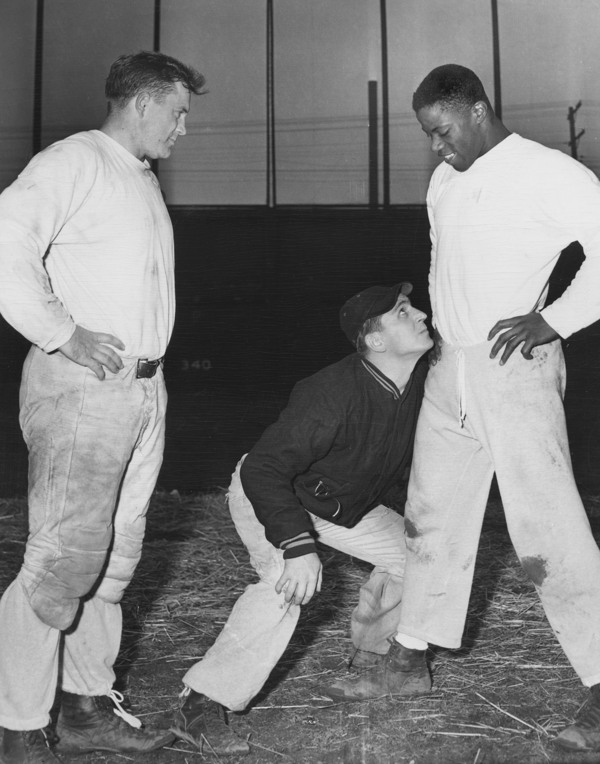

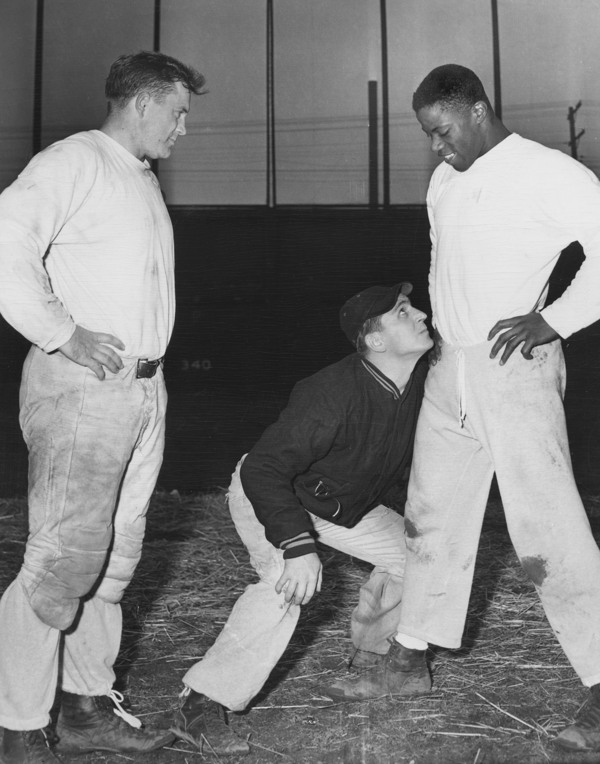

Browns line coach Fritz Heisler tutors Lindell Houston (left) and Bill Willis.

Walsh’s story said Brown was looking for an escape hatch because he was concerned about the future of the AAFC. “I read about it today, and that report probably grew out of a league meeting we had this week,” Brown acknowledged. “I’m not at liberty to say what it was about, but I can say the reason for the meeting was very encouraging for the future. All this talk about the league folding and me moving to another job gets a little tiresome. We have been doing all right, and we’ll end up all right this year. My relations with Arthur McBride and [minority owner] Dan Sherby and others connected with the team have been perfect. They have been grand to me, and our relations are the best.”7

Brown was, however, worried about the AAFC’s future, and, as Harold Sauerbrei noted in his column in the Plain Dealer, it was no secret that USC had coveted his services ever since the Buckeyes, a heavy underdog, routed the Trojans, 33–0, in Los Angeles in October of 1941. The Buckeyes bounced the Trojans again, 28–12, in Columbus in 1942, en route to their first national championship.

Also on the 15th of October, the Colts beat the Dons, 29–14, in front of 40,019 fans in the Los Angeles Coliseum.

The Press reported on the 15th of October that officials of the AAFC and NFL had been asked to allow their champions to meet in a game in December, with the proceeds going to benefit the American Cancer Society. The proposed game would be played in a northern city, possibly Cleveland, if the Browns were AAFC champions. It wasn’t the first time both leagues had been asked to match their champions in a charity game. The AAFC had been interested, the NFL had not. That hadn’t changed by October of 1948.

The Press, in the same article, claimed two unidentified men from Los Angeles wanted to pair the two league’s champions in a “World Series of football” game to be played on Christmas in southern California. The game would serve as a “build up” to the Rose Bowl on January 1st, and the unidentified businessmen hoped to make it an annual affair, if the AAFC and NFL remained separate entities. The NFL was no more amenable to that proposition than it was to the idea of a charity game. But it is worth noting that professional football was still playing second fiddle to the college game in the late 1940s. A “World Series” of professional football game would have been no more than the opening act for the Rose Bowl.

“We’re ready for peace anytime the National League wants it,” said Browns majority owner McBride. McBride and his head coach would’ve been anxious to meet the NFL’s champion after the 1946 and 1947 seasons. But the older league turned up its nose at the thought of acknowledging the AAFC’s existence in such a manner. The bottom line was the NFL had nothing to gain and everything to lose by agreeing to a game between the two league champions.

“I would like to see big league football placed on a sound basis as soon as possible,” McBride continued. “By getting together, the two leagues would both benefit. There’s no point in cutting each other’s throats by competing for these high-priced football players. If we got together tomorrow, salaries would be cut by at least one-third by next season.”

Having led professional football in attendance in 1946 and ’47, and setting the pace again in ’48, the Browns were in no trouble financially, although McBride said he wouldn’t make any money off his football team.

The Browns are in as healthy condition as any team in either league. We can afford to let those National League fellows go along until they quit being so stubborn. They’ve got some fellows in that league with peculiar ideas, but I think they’ll eventually come to their senses.

The cordon of peace between the two leagues is drawing closer. When the National League owners suddenly come face to face with the economics of the thing, I am confident there will be a quick settlement of all differences.

McBride and Brown were on the same page as far as what they wanted that settlement to result in. “I would prefer to see the two leagues continue under a working agreement similar to that in effect in baseball. That kind of competition is much healthier for the sport. I think our league is strong enough to carry on. Chicago is pitifully weak, and I don’t know what will happen there. But Branch Rickey has told me he is willing to continue with football in Brooklyn, and I am confident the Buffalo, Baltimore and Los Angeles franchises can be operated on a profitable basis, once the overhead is reduced. New York, San Francisco and Cleveland can’t miss.”

McBride then repeated the mantra of his fellow owners in both leagues. “The salaries we are paying now are far out of line. A few years ago, the Rams were paying such stars as Vic Spadaccini, Riley Matheson, and Johnny Drake between $1,800 and $3,500 a year. Lou Rymkus was getting $2,200 from the Washington Redskins. Today, some players are getting as much as $25,000. But, thank goodness, we don’t have any salaries that high on our club. Nevertheless, our payroll is $100,000 higher than last year’s. Nobody in either league will make any money this year.”

McBride addressed speculation that dissatisfaction with the financial structure of professional football would lead him to sell the Browns. “The team has never been for sale. I wouldn’t sell it even if I were sure of a nice profit. I’m not making any money, but I’m having a lot of fun.”8 It can be reasonably asked just what McBride, Tony Morabito of the 49ers, Jim Breuil of the Bills, and Ben Lindheimer of the Dons expected when they cast their lot with Arch Ward’s new league. Surely they understood a rival to the established NFL would mean a fierce bidding war for players. No entrenched sports league in the United States has ever welcomed an intruder with open arms and invited the competition for money, fans, and talent. The NFL responded to a challenge to its monopoly on professional football as it would have been expected to: the owners dug trenches and decided to wait out an opponent they were sure they would defeat, and spent the money necessary to hasten that defeat. McBride and the other millionaires who owned AAFC teams may have thought they would have brought the NFL to its knees, or at least to the peace conference table, by mid-season of 1948. If that was the case, they were mistaken, although feelers would be sent out by representatives of both leagues before the season ended.

With Dante Lavelli in uniform and ready to play for the first time in 1948, the Browns took on the Bills before just 28,054 in Municipal Stadium. It was the smallest crowd ever to watch the Browns play at home. Looking at 50,000 empty seats at home games gave Brown pause pertaining to the AAFC’s future. If the league’s flagship franchise couldn’t even fill half of its stadium, it was understandable that Brown might look seriously at an offer from southern California, if one was forthcoming, as the rumors insisted.

Weather may have been partially responsible for the small crowd. The temperature peaked at 55 degrees early in the afternoon on October 17 and dropped as the hours passed. The first snow of the season fell several hours after the game ended.

Cleveland took the opening kickoff and needed just three plays to take the lead. Otto Graham connected with Edgar Jones on a 44-yard touchdown pass, and the Browns were up, 7–0. Later in the first period, Marion Motley’s fumble was recovered by Buffalo’s Chet Mutryn at Cleveland’s 38. A 22-yard pass from quarterback Jim Still to Alton Baldwin tied the score at seven. Lou Groza’s 45-yard field goal untied the score. The Browns marched 52 yards on their next possession, with Graham hitting Mac Speedie twice for gains of 18 and 19 yards. Motley carried the ball in from the three, and that ended a busy first quarter with the Browns ahead, 17–7.

After a scoreless second period, Cliff Lewis intercepted Still and returned the ball 20 yards to Buffalo’s 41. Graham’s 15-yard pass to Speedie increased the Browns’ lead to 24–7. With Still failing to move the offense, Dawson relented and inserted Ratterman in the third quarter. Ratterman engineered an 85-yard drive that ended in an eight-yard touchdown pass to running back Lou Tomasetti, and the Bills were within 10 points. They wouldn’t get any closer. With a backfield of Lewis at quarterback, Ara Parseghian and Dean Sensabaugher alternating at halfback, and Ollie Cline at fullback, the Browns drove 70 yards for the game’s final touchdown. Lewis’ only pass of the afternoon was a 30-yard strike to Speedie for the score. Speedie caught six passes for 140 yards.

Once again, the Browns had the upper hand statistically. Cleveland gained 418 yards to Buffalo’s 342. The Browns rushed for 209 yards to 82 for the Bills, but Buffalo gained 260 yards through the air to 219 for Cleveland. Graham threw 27 passes and completed 11 for 189 yards and two scores. Lewis was a perfect 1-for-1. Still completed six of 11 for 86 yards for the Bills. Ratterman came off the bench to toss 24 passes and complete 13 for 174 yards and one touchdown. The Browns intercepted two passes, but lost two fumbles.

“We were not exactly scintillating, but we managed to get by,” said Brown of his team’s performance. “That is exactly what I was afraid of. That the kids would regard this as just another football game. You see, we were at a psychological disadvantage. We had beaten this club twice before, once in an exhibition, so the general feeling was that it would be another victory. Well, Buffalo is not a team that you can regard lightly and, frankly, I’m happy that we got by as well as we did. We’ve got to keep improving week by week, because the tough games are yet to come. We’ve only got four weeks to get ready for San Francisco.”9

Brown admitted that his most difficult task had been getting his undefeated team “up” to play inferior opponents week after week. “We have not been as sharp as we can be and should be. But football is so much of a game of spirit, and it’s been hard for me to steam `em up for these games, and hard for them to steam themselves up.”10 In spite of that, the Browns kept winning.

Brown was asked about Dawson’s decision to bench Ratterman in favor of Still, who couldn’t move the offense. “That’s an old chestnut. I suppose they felt Ratterman needed a lift, so they gave it to him. Ratterman played a marvelous game. If Alton Baldwin hadn’t missed a couple of his passes, we would have been in plenty of trouble.”11 Baldwin missed those passes even though his defender, Tommy James, was having a difficult day covering him.

“James had a rough afternoon,” said Brown. “He had difficulty getting his footing in the mud. Even on a dry field, it’s a tough assignment to guard Baldwin.”12

Baldwin agreed with Brown that a couple of catches he didn’t make could have changed the game’s outcome. “The passes were good. I shoulda had ’em. I think we coulda beat those guys today.”13

Edgar Jones said the condition of the field deteriorated as the afternoon wore on and the day got colder. “It wasn’t so bad in the first half. But you couldn’t get your footing at all in the second half.”14 Tarps had covered the field until a few minutes before kickoff. A chilly rain fell in the fourth quarter.

The afternoon was to have been a special one for Graham. AAFC commissioner Jonas Ingram was supposed to have presented the Browns’ quarterback with the 1947 Most Valuable Player trophy. But Ingram’s plane was grounded in Louisville, Kentucky, and he didn’t make it to Cleveland in time for the game.

As the Browns were pulling away from the Bills, the 49ers had some difficulty with the Yankees, but prevailed, 21–7. A crowd of 29,743 attended the game in Yankee Stadium.

The western standings after eight weeks:

The season was half over. The Browns were perfect, but so far, it wasn’t good enough.