While six of the eight AAFC teams spent the week of October 25 preparing to play the following Sunday, the Browns and 49ers had a week off to rest and relax. Next up for the Browns was a visit from the Colts on November 7. Then came the first of Cleveland’s two showdowns in three weeks with the 49ers, in Municipal Stadium on November 14. Paul Brown allowed his players to get away from the practice field for a few days. Unless they chose not to read the newspapers, however, they couldn’t escape from the debate about the future of the All-America Football Conference.

The AAFC experienced a myriad of problems during its brief existence. One of them was the inability to find a strong leader to guide it in its struggle to gain equality with the NFL. It was likely not a coincidence that the AAFC selected former Notre Dame star Jim Crowley as its first commissioner. Crowley’s teammate with the Fighting Irish, Elmer Layden, was the commissioner of the NFL and dismissed the challenge from the new league with the taunt “Let them get a football!” that has gone down in the game’s lore. Specifically, Layden had sneered, “First get a ball, then make a schedule, then play a game.”1 Perhaps to Layden’s surprise, and undoubtedly to his dismay, the AAFC did all three. Then it produced teams like the Cleveland Browns, San Francisco 49ers and New York Yankees. Any of those teams, in the not unbiased opinion of Brown, could’ve whipped the best the NFL had to offer, if given the chance. And at least one NFL owner, Alex Thompson of the Eagles, was anxious to give the AAFC’s champion that chance.

Crowley signed a five-year contract as AAFC commissioner, but resigned after the 1946 season. In Brown’s autobiography, he expressed the opinion that “Crowley had no real interest in the job.”2 He became involved with the Chicago Rockets, including serving as head coach for the first 10 games of the 1947 season. The Rockets lost them all.

Rather than replacing commissioner Crowley with a football man, the AAFC owners chose retired Admiral Jonas Ingram who, according to Brown, “really knew little about professional football.”3 As the Browns enjoyed a brief vacation on October 25, Ingram addressed separate luncheons of New York City sportswriters and sportscasters, making almost identical speeches to each group. He called the bidding war for players with the NFL “stupid and childish” and denied the incessant rumors that the AAFC was on the verge of collapse. He insisted that the league would operate with the same eight teams in 1949.

“We’re ready to talk peace any time,” said Ingram. “But the next move should come from our adversaries. I’ve done all I could, and I’m not going crawling at anyone’s door.” Of the salary spiral caused by the lack of a common draft, which the AAFC proposed and the NFL rejected, Ingram said, “Certainly this war is hurting pro football. I’m all for the player, but obviously everybody is paying them too much. There are ways to work out an equitable solution, and the things to be accomplished are very simple.”4

Ingram was opposed to a merger of the two leagues, but said steps could be taken to bring the conflict to a conclusion and allow the AAFC and NFL to live happily ever after. In addition to a common draft, Ingram favored coordination of schedules between teams sharing cities to keep both from playing at home on the same day, and relocation of teams from cities that had proven they couldn’t, or wouldn’t, support three teams (Chicago and New York) or two teams (Los Angeles). Ingram didn’t say which teams should vacate such cities, but it was a cinch the Bears, Giants and Rams weren’t going anywhere, even if the AAFC was winning the battle of the box office, as it was in Los Angeles and New York, where the Yankees regularly out-drew the Giants. The Dodgers were another matter altogether.

Ingram was asked about comments made by Browns owner Mickey McBride and Yankees owner Dan Topping about the possibility of some of the weaker AAFC franchises folding. “They were just honest enough to say what others think. It’s a true statement. Our only weak club is Chicago, and it will be in there next year stronger than ever. It may be that Chicago has too many clubs, especially if one of them isn’t winning. We’ll be the weak one there as long as we don’t have a better club. Brooklyn should be able to support a pro club, and Los Angeles is all right for two clubs.”

Ingram was also asked about the rumors swirling around Brown. His name was being linked to every major college head coaching opening from Maine to California, as well as some openings that didn’t yet exist. “As for rumors Paul Brown is about to desert us, and that Cleveland and San Francisco are ready to jump to the other league, we all get temperamental in the heat of things. Brown came to me once before, and I told him, ‘Paul, you have a good job and no alumni to bother you.’ I think he will be around for some time. And I have the assurance of Topping and McBride that they do not intend to jump. I have full assurance that not now, nor ever has, any of the owners indicated a desire to desert the All-America Conference.”5

McBride confirmed that he was on board for the long haul. “I’ll sink or swim with the owners who have invested their money in All-America Conference teams. I wouldn’t cross them up by pulling out now. Furthermore, I think some of our clubs are financially stable as any National League team, and I’ve been told that the Browns would have no trouble beating their champion, the Cardinals.” McBride may have been subtly trying to goad the NFL into trying to refute that claim, made by unidentified sources, by allowing a post-season meeting between the two league champions. If he was, the ploy failed.

“No matter how you juggle the leagues, there still would be losers and winners,” McBride continued. “Someone has to lose or there wouldn’t be a champion. It isn’t healthy for either league to be warring with the other, but I firmly believe both leagues could operate successfully if they came to some agreement.”

McBride also addressed the constant rumors that his team’s head coach would accept a college coaching job for 1949. “His contract as coach of the Browns runs through 1950. He has not asked to be released from it. I don’t know where these rumors about his leaving us for a college job originate. It would be hard to replace him.”6

Those same rumors were addressed by the two athletic directors who had reportedly offered Brown a job coaching at their schools. Said Willis Hunter of USC, “The report is absolutely erroneous as far as we’re concerned.” From Wilbur Jones of UCLA came the brief statement “It’s untrue here, also.”7 The rumors, however, would persist.

Brown sounded like a coach who may have been fed up with his current working conditions, however. “I am disgusted with the bickering and fussing between the National League and our conference. I don’t like fighting between the two leagues and never did.”8

Ingram and the AAFC found themselves with another fire to extinguish on the 27th of October, when the United Press reported that Buffalo Bills owner Jim Breuil, a multi-millionaire oil magnate, had “declared emphatically” that his team would remain in Buffalo and in the AAFC in 1949. Breuil was responding to rumors that the Bills would either be sold or moved out of Buffalo.

Gordon Cobbledick knew why attendance was declining in both the AAFC and NFL, even in Cleveland. The fact that advance ticket sales indicated a sell-out crowd of 80,000 or better when the 49ers visited proved, in the columnist’s opinion, that Browns fans weren’t tired of football or tired of winning. They were, however, tired of the lack of competition the Browns faced. With the Yankees struggling in 1948, the 49ers had emerged as the only AAFC team with a chance to beat the Browns. The prospect of a competitive game was what had fans clutching dollar bills and standing in line outside the Browns’ two ticket outlets in downtown Cleveland well in advance of the game. Cobbledick looked back on the crowd of 80,047 that stormed the gates of Municipal Stadium when the Yankees came to town in 1947, and guessed that even more people would pass through the building’s turnstiles to see if San Francisco could hang with the two-time defending champions. Indications were that they could, and that was luring a potentially record-setting crowd to the lakefront.

The NFL, Cobbledick noted, suffered from the same lack of competition as the AAFC. In the older league, the defending champion Cardinals, Eagles and Bears stood head and shoulders above their competitors. The Cardinals and Bears combined for 21 wins and three losses, explaining why hardly anyone was paying attention to the woeful Rockets in Chicago. The Cardinals, Bears and Eagles were a combined 30–5–1 in 1948. The seven other NFL teams were a combined 29–54–1. Until something resembling competitive balance could be achieved, especially in the AAFC, Cobbledick said attendance in both leagues would continue to decline, even in Cleveland.

Dante Lavelli took advantage of the Browns’ bye to continue strengthening his right leg. Lavelli had returned to action earlier than expected from the broken tibia suffered in the exhibition game against Baltimore. Lavelli played against the Yankees in the season’s seventh game, but caught no passes. He astounded his coaches and teammates by appearing on the playing field one week after the injury, despite the cast on his leg. “Amazing fellow, that Lavelli,” marveled Brown. “Amazing the way he catches passes, and amazing the way he recovered from that broken leg. Just think, it was only seven weeks ago that he got the thing, and there he was today, running full speed and cutting as sharply as if nothing had happened to him. The secret is the condition in which he keeps himself. The doctors who set his leg said it was about as bad a break as one can get, and that we shouldn’t expect too much from him until the last few games of the year. Dante has amazed them, too. They say it’s one of the quickest jobs of calcification they’ve ever seen.”9

While his teammates practiced each day, Lavelli was in the trainer’s room at League Park, getting treatment from Wally Bock. Lavelli stretched out on a table with his leg dangling over the edge. Bock applied pressure on the leg in one direction and Lavelli pressed in the other direction. Lavelli also took part as much as he could in team calisthenics and even managed to do some running. He admitted he wasn’t in football shape and had been tired at the end of the victory over the Yankees. Brown was glad to have him back, even if he wasn’t at full strength. So was Otto Graham.

On October 27, the Yankees announced that Red Strader had been hired as the team’s general manager and head coach for 1949, removing the word “interim” from his title. Topping took the opportunity to set the record straight about the comments he’d made that angered Alex Thompson and torpedoed the “meet and greet” Thompson had arranged between some NFL and AAFC owners.

“When I pointed out last week that football under the current set-up is a losing proposition,” Topping explained, “I did not wish this to be construed as derogatory of any club or individuals. I hope we can all make money some day, and that we can find the set-up to do so.”10

On Halloween, the Bills and Colts staged the biggest offensive explosion in the brief history of the AAFC, at least as far as total yardage was concerned. In the battle for first place in the league’s eastern division, the Bills beat the Colts, 35–17, as a crowd of 23,694 in Civic Stadium cheered them on. The two offenses combined for 893 yards gained, breaking the previous record, set in 1947 by the Bills and 49ers, by 13 yards. Buffalo and Baltimore were tied for the division lead with 4–5 records.

In New York, the Yankees were a game behind after their 42–7 drubbing of the Rockets, witnessed by 13,239 in Yankee Stadium. Nearby, in Brooklyn’s Ebbets Field, the Dons blanked the Dodgers, 17–0. There were 12,825 fans in attendance in Flatbush.

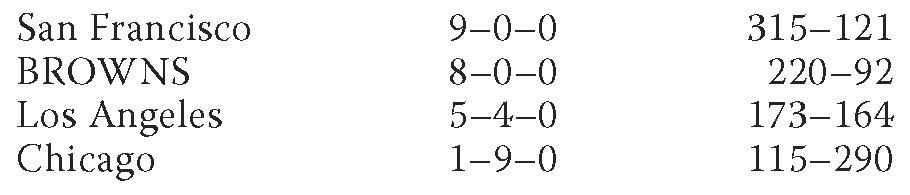

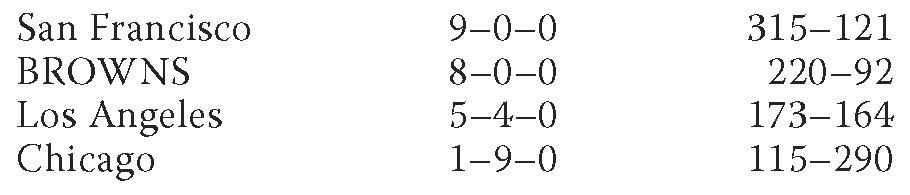

The western standings after nine weeks:

It was time for the Browns to go back to work.