Browns 14, 49ers 7

Another week, another rumor.

This one wasn’t a rumor in the truest sense. Although the headline in the November 8 edition of the Plain Dealer said that Paul Brown’s name had been linked to the positions of head football coach and athletic director at the University of Pittsburgh, the story beneath it didn’t say anything of the kind. It said that Pitt would undoubtedly be looking to replace football coach Mike Milligan, who was in his first year on the job, after the Panthers had been routed by Ohio State, 41–0, two days earlier. The Buckeyes were coached by Wes Fesler, who’d been Pitt’s coach in 1947 before returning to Columbus to coach his alma mater.

Someone identified only as “a Pitt follower” was quoted as saying, “Fesler definitely would have been the end to all of our troubles. We are looking for someone like him to handle the whole job.”1 The unattributed story recounted the recent history of Pitt football, noting that the school’s administration decided to de-emphasize the sport after the departure of coach Jock Sutherland in 1938. Since then, the team had been coached by Charley Bowser, Clark Shaughnessy, and Fesler. Students and alumni had been agitating for some time for the administration to put more emphasis on the program, in order to restore the Panthers to their former place of importance in eastern football. Acting athletic director Frank Carver didn’t want the job, and Milligan, especially after the pasting from Ohio State, didn’t appear to have what it took to turn the football team around. Then the story mentioned that Brown would be a logical choice for the Panthers. Pitt, it was noted, could pay a handsome salary, but couldn’t compete with the Browns in the compensation department. Brown was too busy preparing his team for the 49ers to waste time commenting on more uninformed speculation.

Advance ticket sales indicated the Browns would break the team attendance record against the 49ers. The record was set in 1947, when 80,047 watched the Browns and New York Yankees. And those in attendance would witness history. What would take place in Municipal Stadium on November 14 had never happened previously in professional football. And it hasn’t happened since. The combatants would bring a combined record of 19–0 into the game. Never before had two teams with no defeats and 19 victories between them met in a professional game. At least, not in what could reasonably be considered the game’s “modern era.”

The Browns entered the game well represented among the AAFC’s individual leaders. Marion Motley was the league’s top rusher with 741 yards on 115 carries, for an average of 6.4 yards per rush. Mac Speedie topped the league’s receivers with 50 catches for 713 yards, an average of 14.2 yards per reception. Otto Graham was third in passing with 114 completions in 212 attempts for 53.8 percent accuracy in an era when most quarterbacks were lucky to complete half of their passes. Graham’s passes had gained 1,688 yards for an average of 14.8 yards per completion (or 7.96 yards per attempt). Graham had thrown for 16 touchdowns. He’d also run for 113 yards, and was third in the league in total offense with 1,801 yards.

An influx of rookies were partly responsible for San Francisco’s perfect record. Halfback Forrest Hall, from the nearby University of San Francisco, weighed just 155 pounds, but gave the 49ers breakaway speed they’d lacked previously. Other significant first-year contributors were fullback Verl Lillywhite from the University of Southern California; halfback Jim Cason from Louisiana State; ends Harold Shoener of Iowa and Gail Bruce of Washington; and tackle Bob Mike from UCLA. But the most important addition may have been a player familiar to Cleveland football fans. A player who almost became a Brown.

Defensive guard Riley Matheson had been playing pro football since 1939, when he joined the Cleveland Rams. Matheson starred on the Rams’ 1945 NFL championship team, then expressed an interest in jumping to Cleveland’s entry in the new AAFC. The Browns were interested in signing Matheson, as long as he was available, which he wasn’t. The Rams produced a two-year contract Matheson had signed before the 1945 season began. Matheson suggested that he’d been coerced into signing the pact, and threatened briefly not to honor its second season. But he was contractually obligated to the Rams and decided not to follow the same path as his teammates Don Greenwood, Tom Colella, Chet Adams, Mike Scarry and Gaylon Smith, who also wanted to stay in Cleveland when Dan Reeves moved the Rams to Los Angeles. Greenwood, Colella, Adams, Scarry and Smith went to court and argued, successfully, that they’d signed contracts with the Cleveland Rams. When Reeves shifted the team to the west coast, their attorneys claimed, the players’ contracts were automatically voided. The court agreed, and they signed with the Browns. Matheson ironed out his differences with Rams management and stayed with the team through 1947. He and the Rams reached a parting of the ways after the season, and he hooked up with the 49ers, providing a steadying veteran presence the young team needed.

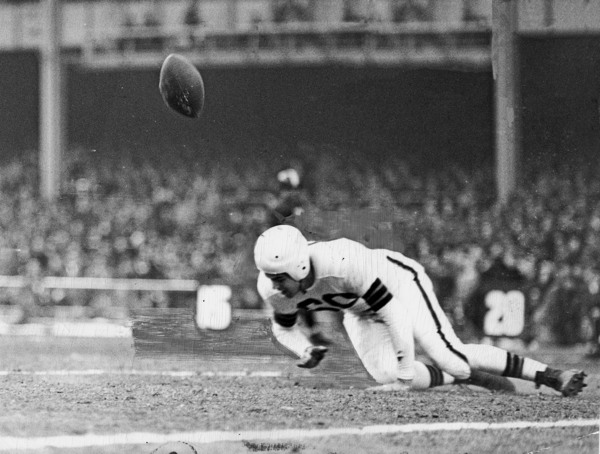

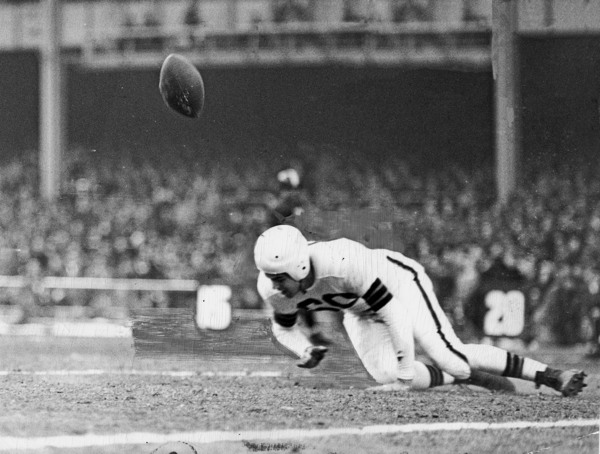

Otto Graham (wearing number 60 rather than his more familiar 14) was as good at breaking up passes as throwing them. Graham was a starter in the Browns' defensive backfield in 1946 and 1947.

“Riley is a great Sunday player, which is all we ask of him,”2 said an unidentified San Francisco scout. Matheson was brimming with confidence when the 49ers arrived in his old stomping grounds for their game with the Browns. “I’ve seen a lot of college football, and I’ve played a lot of pro football, but what I want to know is, who is going to beat us?”3 he asked. The 34-year-old veteran would have his question answered the following Sunday afternoon.

If the Browns were going to beat the 49ers and take possession of first place in the western division, they’d have to put the clamps on star quarterback Frankie Albert. Brown and his coaches were working on a plan to do just that. “The thing people overlook when discussing Albert is that he is a very good runner,” said the coach. “That’s one of the things that makes him so hard to stop. You very seldom see a quarterback in the T-formation run the way Frankie does. And sometimes when he starts out on what looks like a run, he’ll cross you up by throwing the ball. It’s something like the double wing formation used to be, where the fellow with the ball would start to his right, and continue to run or throw the ball, depending upon conditions.”4

The Browns were familiar with the 49ers’ left-handed quarterback. Albert and his teammates handed the Browns their first loss, a 34–20 setback in Cleveland on October 27, 1946. They’d lost only two other games since then. Brown’s top assistant, Blanton Collier, remembered the game well.

“I can’t forget that one,” reminisced Collier. “I had scouted the 49ers the week before and came away with the thought that I never knew more about a team. But Albert was hot, we lost, and the thing that worries me is Albert is playing this season just as he did that day against us. He isn’t relaxing against anyone. When I was in San Francisco recently, people out there said Albert had definitely made up his mind to make a career of pro football, that in other years it was merely a matter of picking up some money before going into the building business with his brother. The new attitude is certainly reflected in his performance.”5

A national magazine in late October proclaimed Albert the premier quarterback in professional football. Harold Sauerbrei in the Plain Dealer compared Albert to Graham, and perhaps surprisingly, Graham came out on the short end. In Sauerbrei’s opinion, Albert was faster than Graham, a better ball handler than Graham, and had the desire to be a master craftsman. Graham was a better passer than Albert, but lacked his upcoming opponent’s drive for perfection. In their head-to-head match-ups, Graham had completed 67 percent of his passes against the 49ers for 1,020 yards. Albert hadn’t fared well against the Browns except in the upset victory of October 1946, when he completed 14 of 21 passes for 180 yards and three touchdowns.

An unidentified AAFC game official said he particularly enjoyed working 49ers games because of Albert. “I get a big kick out of working 49ers games, just to listen to Albert,” admitted the referee. “He has so much confidence in himself that he’ll talk loud enough in the huddle to let the other team know what play he’s going to call. In one game, he took his position under center and cried ‘boys, it looks as if they’re ripe for a quarterback sneak.’ And darned if he didn’t sneak over for the touchdown.”6

The 49ers arrived in Cleveland three days before the game. “We have been hot most of the time, but we have been pretty lucky, too,” said head coach Lawrence (Buck) Shaw.

Naturally, we’re better than last year, but we have some weak spots, too, in spite of what the record shows. I suppose the biggest single factor is Albert, and I owe a lot to Clark Shaughnessy for the way Frankie is playing this year. Frankie went to Los Angeles during the summer and saw his old college coach [Shaughnessy] down there. Clark told him that [Washington Redskins quarterback] Sammy Baugh is getting better every year and expects to play five more years, and that he ought to take football more seriously. Frankie heeded the suggestion, and he’s been terrific.

We have a few weak spots, too, notably at tackle, where we have been going most of the year with three men, Bob Bryant, Bob Mike, and John Woudenberg. Fortunately, there have been no injuries, except to Bruno Banducci, who suffered a dislocated shoulder. But he’ll be able to play some Sunday. He is due for an operation after the season is over, but the doctor said it’s all right for him to play until then.

Shaw talked about the turnover of personnel between 1947 and 1948. “We have only 14 of last year’s team with us, but they have been the steadying influence for the new men, and this Riley Matheson has been a tremendous help. He holds our rookies together on defense. It’s uncanny the way he can diagnose the opposition’s plays. But it hasn’t been all one-sided. The rookies, with their fine spirit, have given the veterans a lift in that respect. The result is that we’ve been winning, everyone is high, and when you get that combination, everything is fun.”

Shaw said the 49ers lacked the depth of the Browns, “and that, and Dante Lavelli, Mac Speedie, and Otto Graham will hurt us.”7

Shaw attributed part of Albert’s success to San Francisco’s rushing attack, led by halfback John Strzykalski. Once the property of the Browns, Strzykalski had gained 635 yards on 94 carries for a 6.75-yard average, the best per-carry average in the AAFC. “Albert’s been great. So have our ball carriers and so have our ends,” said Shaw. “But we’re not kidding ourselves about the Browns. They’re the team we have to beat. If we don’t, nothing we’ve done up to now will matter.”8

Shaw was asked about a photocopy of an article from a San Francisco newspaper, expanded in size and posted on the bulletin board in the team’s dressing room. It was printed the day after the Browns had defeated the 49ers, 37–14, in the second meeting between the two teams in 1947. In an uncharacteristic moment of bravado following the victory, Brown was quoted as saying, “I wanted to convince the San Francisco team that we could lick ’em, and lick ’em good. They know it now, and they’ll remember it next year.”9 Cleveland’s previous two games against the 49ers had been decided in the Browns’ favor by 14–7 scores, and that apparently hadn’t been satisfactory to their coach. Shaw dismissed the posting of the article for his players to gaze upon as a prank.

“I don’t know whose idea it was [to display the photocopy], but I know our club doesn’t need any special pepping up when we play the Browns. We know how good the Browns are,”10 he said. The “next year” Brown referred to had arrived, and the holdovers from the 1947 49ers surely did, as Brown knew they would, recall the 23-point drubbing Cleveland had handed them.

Having played in both the NFL and AAFC, Matheson was asked to compare the two leagues. “The National League might be a little better on the line,” he responded, “but I never saw any backs who could compare to the boys in this league.”11

Brown put his team through its longest practice of the season on Thursday, November 11. Collier spent 90 minutes with the defensive players in the classroom, then Brown put them through their paces for two and a half more hours on the field. The marathon session was devoted to defense, and with good reason. The 49ers were averaging 36 points per game. “There is no doubt about it, our linebackers should be given a major share of the credit for the fine record we have made against running attacks this year,” Brown said. “It’s sort of a team proposition, but those three fellows have been making a lot of tackles. Adamle and Humble, with a year’s experience in this league behind them, have been great. Adamle, of course, is carrying on the fine work Motley did on the left side for two years. And how can you say anything new about Saban?”12 Because Adamle was playing so well, Brown was able to use Motley almost exclusively on offense, which was the way the coach preferred it.

If they were to defeat the 49ers, the Browns would also need another strong afternoon’s work from the defensive ends, Chubby Grigg and Chet Adams. Adams had no doubt that he was playing for the best team in football. “We might beat such teams as the Cardinals and Bears by no more than one point, three points or one touchdown,” said the veteran who’d turned 33 in October. “But I’m convinced we would beat them. We would win because of three factors: organization, speed, and condition. We’re far superior to those teams in those departments.”

Adams saw a clear difference between the AAFC and NFL in the individual team’s approach to the game. “There’s more stress on fundamentals in the All-America. Players going to the National are presumed to know how to block and tackle, but many don’t know how. In this league, and especially with Brown’s teams, the emphasis on fundamentals is as strong in late season as it is at the summer camp.”

Adams was another local product, having played at Cleveland’s South high school and Ohio University. He was asked if he thought the 1948 season might be his last. “You never know,” he responded with a smile. “Brown is honest about telling his players when it’s time to quit. He may can me at the end of this year.”13 Adams sounded as if he was kidding, but 1948 would be his last season with Cleveland. He’d play for Buffalo in 1949 and the New York Yanks of the NFL in 1950.

Brown scaled back practice to an hour on Friday. “The heavy work is over for us now,” he said. “From now on, it’s sort of up to the boys to get themselves ready.”14 Shaw’s 49ers practiced in private at Western Reserve University, rather than on the field at Municipal Stadium. “Nothing important,” Shaw said when asked about the secrecy. “We just think it’s better to work in private. We’re as ready as we’ll ever be.”15

Sauerbrei quoted an unidentified member of the 49ers entourage as saying, “It sounds inconsistent, but that rainy night in Baltimore [October 5], the 49ers were in Cambridge Springs, Pennsylvania, listening to the game on the radio and actually pulling for the Browns to win. They wanted them to come down to this game unbeaten as badly as they wanted a record like that themselves. They don’t want any advantages. They’re not cocky, just confident of what they can do.”16

As for his team, Brown said his players were so pumped up for the 49ers, “if I went to them today and told them, ‘boys, I’m sorry but the treasury is empty and we’re not going to be able to pay you a dime for Sunday’s game,’ they would still go through with it and give everything they had to beat the 49ers.”17

If experience counted for anything, the Browns had a distinct advantage. Twenty-four of Cleveland’s 33 players had three years experience in the AAFC. San Francisco had 19 rookies on its roster. And rookie jitters may have accounted for the early hole the visitors dug themselves.

As a crowd of 82,769 looked on, San Francisco’s scatback Forrest Hall fumbled the opening kickoff. Saban recovered, and the Browns had a 7–0 lead three plays later. Graham tallied on a 14-yard scramble after being unable to find an open receiver. The 49ers quickly shook off the shock of trailing so early and tied the score at seven with an 80-yard march that climaxed with Joe (the Jet) Perry’s one-yard run. Neither team scored in the second period as the Browns couldn’t capitalize on a recovery by John Yonakor of a fumble by Strzykalski on San Francisco’s 39-yard line. Lou Groza failed to convert a 48-yard field goal attempt. Bill Boedeker squashed another Cleveland scoring opportunity by losing a fumble at the San Francisco 20.

The Browns took the second half kickoff and Graham drove them 84 yards for what proved to be the game-winning touchdown. Two passes from Graham to Bob Cowan and one to Ara Parseghian, totaling 55 yards, put the ball close to the 49ers’ end zone. Edgar Jones carried it in from the four-yard line.

The Browns appeared to be on their way to expanding their 14–7 lead later in the third quarter. Graham drove the offense to the San Francisco 15, but his pass was intercepted by Verl Lillywhite in the end zone to eliminate the threat. The 49ers reached Cleveland’s 27-yard line halfway through the fourth quarter, but Stryzkalski fumbled and Bill Willis recovered. The Browns killed almost all of the seven and a half minutes remaining. The 49ers got the ball back with enough time to run three futile plays.

The emphasis Brown and his staff placed on defense in practice paid off. The 49ers came to town averaging 426 yards of offense per game. The Browns limited them to 185. Albert had his worst game of the season, completing just six of 15 passes for 32 yards. Graham clicked on 12 of 26 for 147 yards. Cleveland’s rushing game produced 179 yards. The usually solid rushing defense gave up 153, well above its season’s average.

“We busted them, but we got busted up pretty well ourselves,”18 said Brown in the victorious locker room. The victory had come at a price. Speedie suffered a separated shoulder and wouldn’t play against the Yankees in New York the following week, as the Browns began a season-ending four-game road swing. Willis had been either kicked or punched in the face and had a bruise under his left eye. Tommy James had a bruise above his left ankle. Graham’s throwing hand had been stepped on and was bruised and swollen. Weldon Humble received a cut on his chin.

Willis and James were expected to join Speedie on the sideline the following week. Brown raved about the performance of Parseghian, who substituted for the injured James in the Browns’ defensive backfield.

“How about that little guy?” asked Brown. “He certainly can go, can’t he?”

Brown revealed that Willis wasn’t supposed to be on the field when he fell on Strzykalski’s fumble in the fourth quarter to protect Cleveland’s slim lead. “He hurt that cheek bone, and I tried to keep him on the bench,” said Brown. “But every time they got the ball, he always took the field with our defensive team, without a word from me.” Willis’ tenacity may have saved the Browns’ undefeated season.

Brown also had words of praise for Grigg, who played another strong game at defensive tackle. He continued to marvel at how the Browns had obtained Grigg. “Can you imagine? The Chicago Rockets gave him to us for nothing. They just threw him in on a deal. And look what he does for us.”19

Albert’s career year came to an abrupt halt in Municipal Stadium. “We didn’t deserve to win because we made too many mistakes,” he said. “I was just plain lousy.” Asked to elaborate about the mistakes, Albert said, “Now that would be telling, wouldn’t it? Never you mind. We won’t make them when we play the Browns again, that’s all.”20

Shaw had an explanation for the ineffectiveness of the 49ers’ vaunted passing attack. “They were knocking our ends down in scrimmage,” he complained. “The only time we could get loose was when we spread our ends.”21

Shaw lamented the two lost fumbles in the first quarter, particularly Hall’s bobble that enabled the Browns to score in the game’s opening two minutes. “The fumbles in the first period hurt us plenty. I don’t want that to sound like an alibi, though. The Browns played a mighty fine game. I think we can take them the next time.”22

Shaw attributed the defeat largely to his players’ nerves. “I think we were tightened up. About half our club consists of first-year men in pro ball, you know. They were in awe of the Browns. We gave away one touchdown—that first one—as a gift. But the other one was really earned by the Browns. They’re a good, solid team. But we just couldn’t get the ball often enough. When you consider that the Browns had the ball about 75 percent of the time, our boys must have played good ball to keep the score as close as it was.”23 Shaw confidently added, however, “It will be different out on the coast. Our boys will know what to expect, and they will be more relaxed.”24 That opportunity would come in just two weeks.

AAFC commissioner Jonas Ingram was in Cleveland to watch the tussle between the best teams the league had to offer. “It was a marvelous game,” said the admiral. “These are two evenly matched teams. I enjoyed every minute of it.”25

So did Matheson, despite San Francisco’s defeat. “It was a real pleasure to come back to Cleveland, even though we did get beat,” said the ex-Ram. “At least we have the comfort of knowing that it took the best outfit in the business to snap our winning streak.”26

The 82,769 fans who, according to estimates, consumed 50,000 hot dogs, 30,000 bags of peanuts, and 5,000 gallons of coffee and hot chocolate on that mid–November Sunday afternoon, enjoyed the game as well. The fans heard the voice of owner Mickey McBride over the stadium’s public address system: “LADIES AND GENTLEMEN AND FOOTBALL FANS, BECAUSE THIS IS THE LAST HOME APPEARANCE BY THE BROWNS, WE WOULD LIKE TO TAKE THIS OPPORTUNITY TO THANK YOU SINCERELY FOR YOUR SUPPORT. PAUL BROWN AND I WILL CONTINUE TO STRIVE FOR SUCCESS. WE PROMISE THE BEST FOOTBALL SHOW IN AMERICA.”

Thanks to the AAFC’s odd scheduling, the Browns had played five consecutive games at home. The huge throng at the San Francisco game gave them a total attendance of 317,899, or 45,414 per game. That figure would lead the league for the third straight year, but represented a steep decline from 1947. The Browns had attracted 392,760 fans in 1947 for an average of 56,108. In 1946, the Browns had played before 399,962, averaging 57,137 each game. Only two home games had drawn crowds of less than 57,000 in 1946. In 1948, only two games had drawn crowds of more than 57,000.

The western standings after 11 weeks:

Elsewhere in the AAFC on November 14, the Dons beat the Bills, 27–20, before 23,725 fans in Buffalo. Baltimore polished off Chicago, 38–24, as 21,899 watched in Babe Ruth Stadium, and New York topped Brooklyn, 21–7, in a game described by the Associated Press as “the season’s dullest in [Yankee Stadium], providing hardly enough action to keep the paying customers awake.” The game drew a gathering of 15,555 to watch what the AAFC thought, and fervently wished, would become a bitter rivalry. It was hoped the Yankees-Dodgers rivalry in football would equal the Dodgers-Giants rivalry in baseball. Across the Harlem River from Yankee Stadium, in the Polo Grounds, the Giants lost to the Rams, 52–37. A crowd of 22,766 watched that game. For one afternoon, the NFL had bested the AAFC in the battle for New York.

Next for the Browns: Branch Rickey’s brainstorm of three games in eight days in three different cities on both coasts.